Towkays at Home in Singapore

Mandalay Villa. House of Jade. House of Teo Hoo Lye. Yap Jo Lin gives us a tour of three opulent homes from the early 20th century.

The role of an archivist at the National Archives of Singapore (NAS) mainly involves taking care of the archives’ valuable records. However, an equally important part of an archivist’s job is to highlight and showcase to the public the interesting and varied records in the collections of the NAS. One of these collections is the Building Control Division (BCD) Collection, which consists of around 246,000 plans prepared between 1884 and 1969.

These plans were part of an effort by the government to ensure that buildings erected in Singapore were structurally sound. Based on that collection, as well as other resources at the National Library and NAS, this photo essay showcases three homes and their owners: Mandalay Villa, which belonged to Lee Cheng Yan and his son Lee Choon Guan; House of Jade owned by Aw Boon Haw; and the House of Teo Hoo Lye at Dhoby Ghaut. All three homes were constructed in the first three decades of the 20th century.

These men were successful towkays (business owners) who had also made significant contributions to society. Some took up leadership roles, such as by serving on the Legislative Council (Lee Choon Guan), as a Justice of the Peace (Lee Cheng Yan), or on the committee of the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce (Teo Hoo Lye). They also supported various philanthropic causes: Aw Boon Haw, for example, was reported to have given away some $10 million in his lifetime.1

It wasn’t just the men who were generous though. In 1918, Mrs Lee Choon Guan (née Tan Teck Neo) was awarded the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (also known as the MBE) for her contributions during World War I, which included helping the Red Cross look after wounded soldiers and civilians.2 She is believed to be the first Chinese woman to have been conferred the award.

MANDALAY VILLA

In the days before land reclamation along Singapore’s eastern coastline, Mandalay Villa at 29 Amber Road would have stood by the Katong seaside, roughly where the Amber Road roundabout junction with Marine Parade Road is today.3

Mandalay Villa (efforts to uncover the origins of the name were unsuccessful) was built by prominent Peranakan businessman Lee Cheng Yan as a holiday home. Lee was one of the Chinese businessmen who partnered Dutchman Theodore Cornelius Bogaardt in 1890 to form the Straits Steamship Company, which eventually became part of Keppel Corporation. Other tycoons who were part of Straits Steamship include Tan Jiak Kim and Tan Keong Saik.4

Lee’s son and successor Lee Choon Guan made Mandalay Villa his residence. The latter lived there with his second wife, Tan Teck Neo, who was better known as Mrs Lee Choon Guan. She was the third daughter of Tan Keong Saik, after whom Keong Saik Road is named.

The two-storey Mandalay Villa was designed in 1902 by the architectural firm Lermit & Westerhout. The entrance hall opened into a huge living-cum-dining room which stretched over the entire width of the house, or more than 21 m. The ground floor also had an office, which was bolted shut with horizontal iron bars every night, as it had three iron safes in it.5

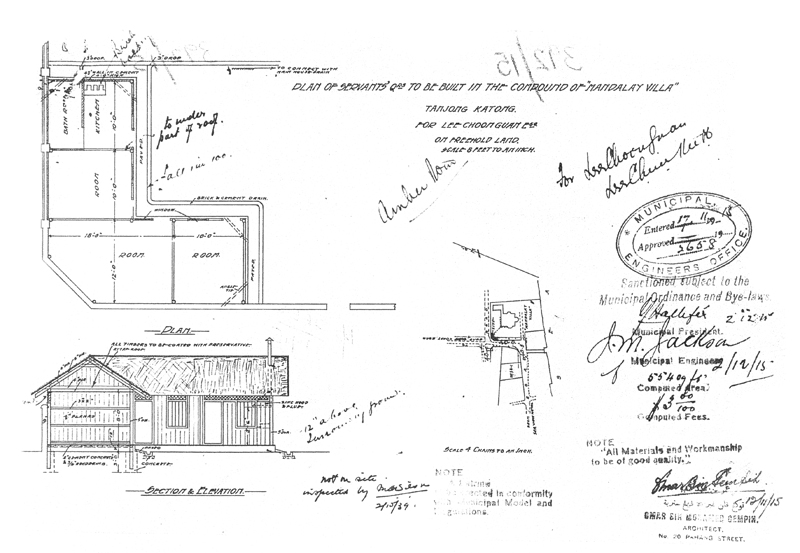

The building plan from 1915 (see overleaf) depicts additional servants’ quarters that were to be added to the Mandalay Villa compound and gives us a sense of the more modest buildings behind the “big house”.

This plan includes a site plan of the property, which shows the front, semi-circular section of the house – where the verandah was – overlooking the sea. The verandah was an ideal place to enjoy the sea view, cool breeze and lapping waves.

Not surprisingly, it became a prime spot for the family to relax and unwind. Mrs Lee would have her daily afternoon tea there at 4 pm and “sun downer” cocktails at 6 pm. Furnished with rattan armchairs and long garden benches to comfortably accommodate 14 people, the verandah was also used for entertaining the many guests and visitors calling on the Lee family.6

Mrs Lee was known for hosting many glamorous social events at Mandalay Villa, the most important of which were held on her birthday on 18 December. The who’s who of Singapore society would be invited to a lavish party, both Europeans and Asians, and the fishermen of Kampong Amber would hold a parade in Mrs Lee’s honour. This was their way of thanking the family for letting them live in the kampong almost rent-free.7

Giving us a sense of the guest list and the scale of such parties, a Straits Times article in 1931 reported that at Mrs Lee’s birthday dinner that year, the Sultan of Johor proposed a toast to Mrs Lee’s health and the Chief Justice replied on her behalf.8 There were more than 400 guests, who were entertained by ronggeng (Malay folk dance), wayang (Chinese opera) and fireworks.9 Mrs Lee’s grandson Herbie Lim recalled that during such parties at the house, talcum powder was often spread on the tiled floor to make it more slippery and suitable for after-meal dancing.10

Mr Lee Choon Guan died in 1924, at the age of 56. Mrs Lee, however, outlived her husband by 50 years, and died in 1974 at the ripe old age of 101. She resided in Mandalay Villa until her death. We are unable to ascertain when Mandalay Villa was demolished though.

HOUSE OF JADE

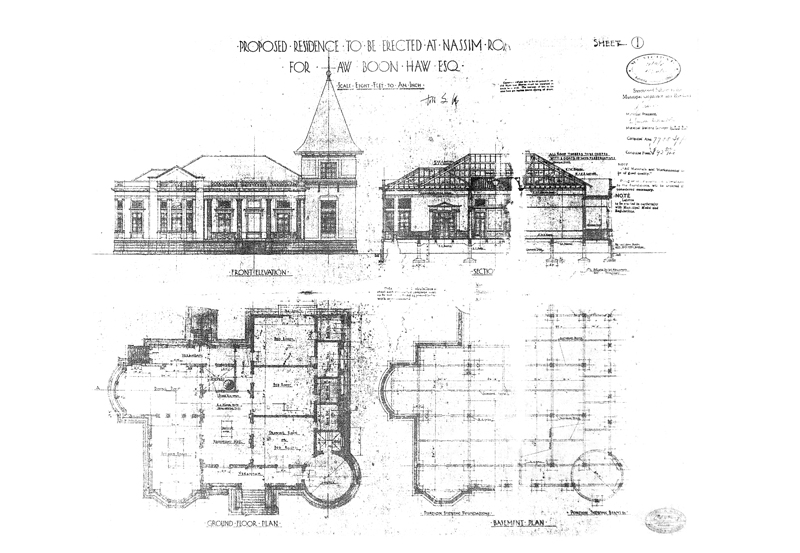

The House of Jade at 2 Nassim Road was built by “Tiger Balm King” Aw Boon Haw, founder of the Tiger Balm brand of medicinal ointments. This was one of those rare houses with its full name prominently displayed on the facade: “Tiger Oil House of Jade”. A tiger’s head adorned the facade beside the letterings and tiger statues guarded the front entrance to the house, on either side of the front steps.

In planning the house, Aw was adamant that it “must be modern yet traditional”, dignified in appearance and be painted white. It was referred to as the “White House” by employees, while family members called it the “Big House”.11 The four Ionic columns at the entrance bear some resemblance to the north entrance of the White House in Washington, D.C.

According to Aw Swan, a son of Aw Boon Haw, the family had initially lived in another house next to the plot of land on which the House of Jade was later constructed. There was a nearby dhoby (laundry) shop that the family sent their washing to, and this dhoby used the vacant plot to dry clothes. One day, however, Aw Boon Haw found out that the dhoby was charging him a higher price than his other customers. Although the sum of money was small, just a few more cents, Aw was angered by the principle of the matter.12

According to Aw Swan, his father “dismissed the man without another word and then muttered something about teaching a crook a lesson he would never forget”. Aw Boon Haw bought the plot of land, fenced it off and decided to build his new residence on the land, thereby depriving the dhoby of space to dry his laundry.13

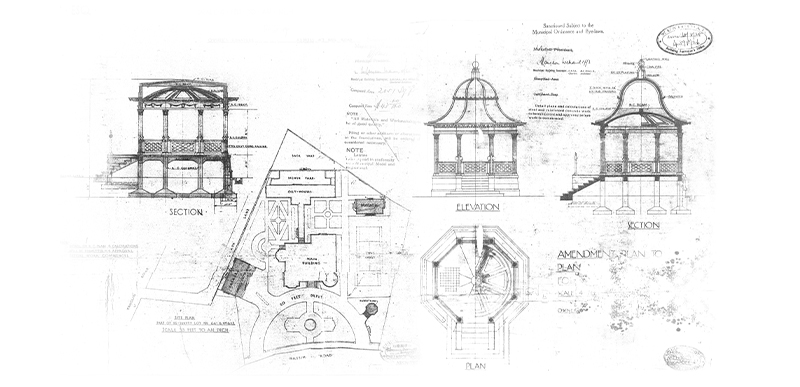

The House of Jade was designed in 1926 by the architectural firm Chung & Wong, whose stamp is seen on the bottom right of the building plan. All the main rooms of the house were located on the ground floor, although the house also had an attic, a basement as well as an impressive tower.

The building was situated within extensive and well-planned-out grounds. There was even an outdoor pavilion erected on the compound. It would have been useful for musical performances.

One of the occasions for such musical performances was at the housewarming that Aw held in September 1928 upon the completion of his new residence. Aw held three housewarming parties to accommodate all his friends. The Malaya Tribune reported that the Merrilads, a Peranakan performing arts group, performed at one of the parties, and their performance was enjoyed by both the party guests and hundreds of spectators gathered outside the house.14

As its name suggests, the House of Jade was especially famous for its collection of jade and other carved minerals. Aw was an ardent collector of jade and jadeite carvings, and had a nose for sniffing out good deals and investments. By 1936, his jade exhibits had grown to become the biggest private collection in the world. Foreign dignitaries and visitors from around the world viewed the collection while visiting Singapore. They included Queen Ratna of Nepal; Princess Anne of the United Kingdom; President Varahagiri Venkata Giri of India and his wife; the Governor-General of Trinidad and Tobago, Sir Solomon Hochoy, and his wife; and Mrs Hiroko Sato, wife of Japanese Prime Minister Eisaku Sato.

The collection was not just open to visiting dignitaries but to the public as well. After Aw’s death in 1954, the collection remained open for public viewing until the family donated most of the items to the National Museum of Singapore in 1979. An exhibition of the Haw Par Jade Collection was opened at the museum’s art gallery in January 1980, and items from the collection were again on display at the museum’s 2010 exhibition, “Singapore 1960”.15

House of Jade was demolished in 1990 and replaced by the Nassim Jade condominium.16

HOUSE OF TEO HOO LYE

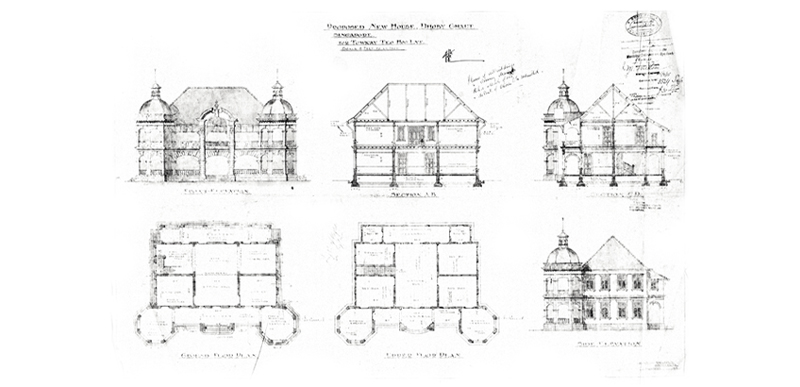

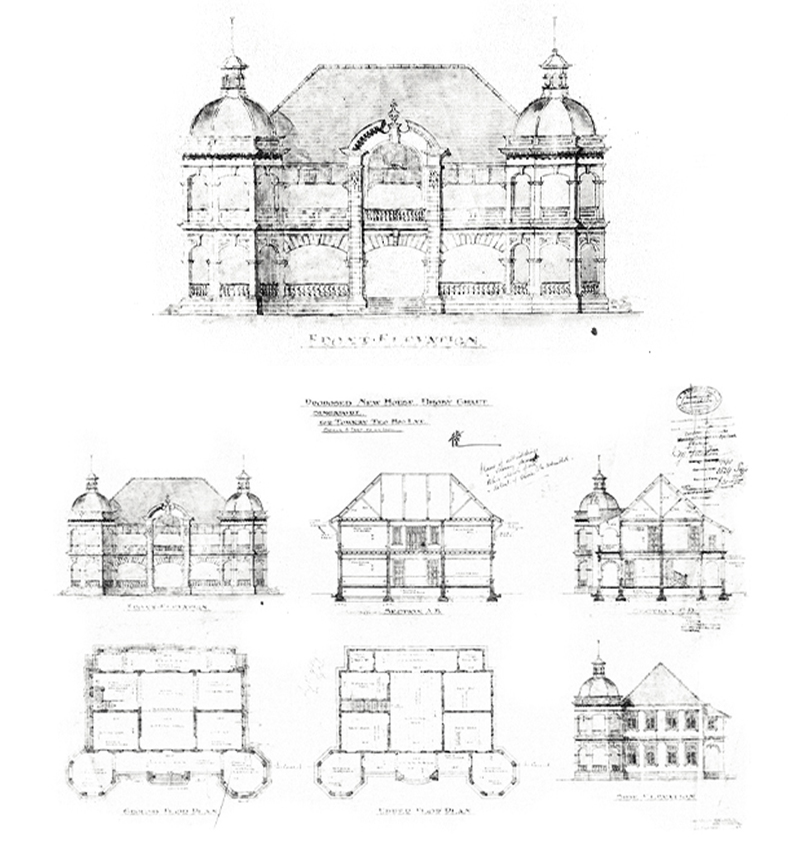

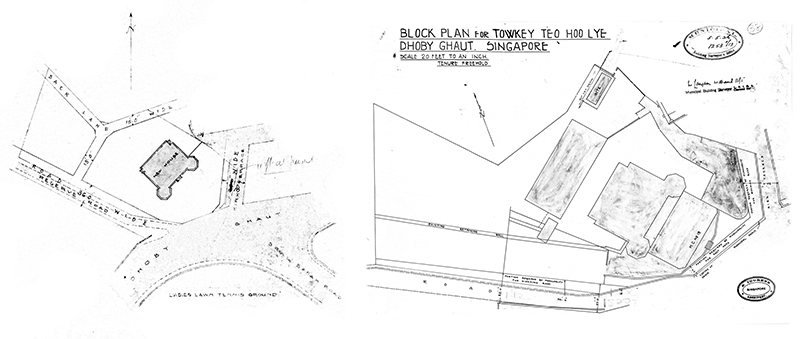

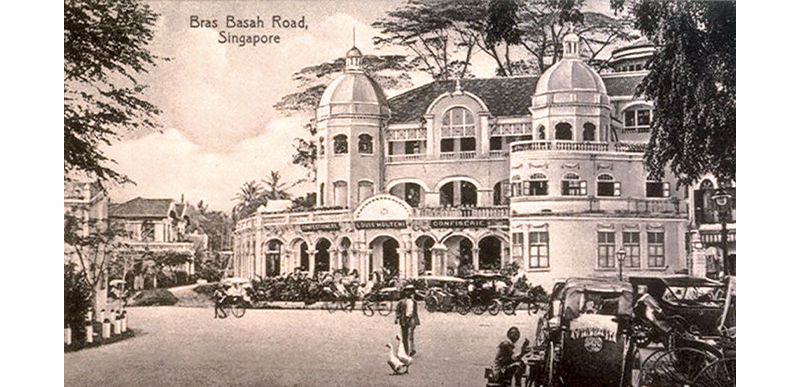

Designed by Swan & Maclaren, the house of Chinese businessman Teo Hoo Lye was located at the junction of Dhoby Ghaut, Kirk Terrace and Bras Basah Road, where Cathay Building now stands.

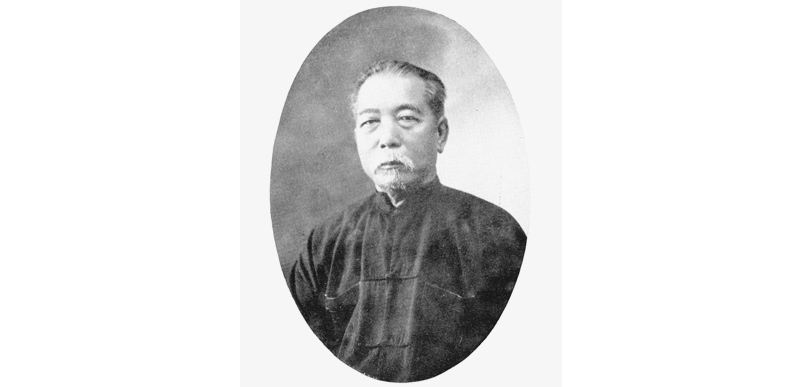

Teo’s life story is the quintessential tale of the immigrant from China who comes to Singapore with nothing, and makes a name for himself through sheer hard work and a shrewd business acumen. Teo was born in 1853 and arrived in Singapore when he was 18. He first found work as a manual labourer, earning just $2 a month, but later decided to venture into business.

Starting out with a modest grocery store on Rochor Road, Teo expanded his business until it eventually included trading in copra (dried coconut kernels), sago factories in Cebu and Sarawak, and a fleet of steamers for transporting commodities. At the time of his death on 16 November 1933, he was said to have more than 14 steamships in his fleet.

Teo was also one of the founders of the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce and Sze Hai Tong Bank. Despite his massive wealth, Teo was described in a Malaya Tribune obituary as a reserved man who led a “simple life and refrained wholeheartedly from entering into the realm of politics”.17

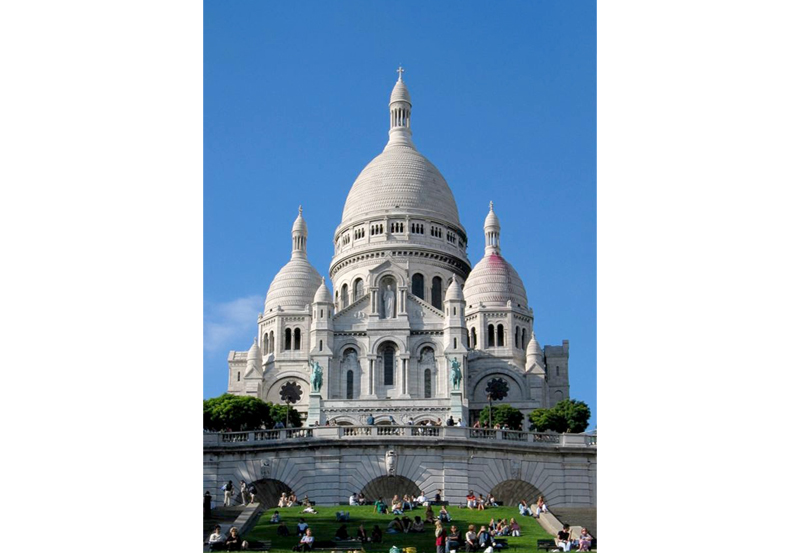

The architectural historian Julian Davison has described Teo’s house as being French-inspired, resembling the Basilique du Sacré-Coeur de Montmartre (Sacred Heart Basilica of Montmartre) in Paris.18

Teo made many additions to his property over the years, which can be seen when comparing the original 1913 site plan with a later one in 1926.

Teo appears to have lived in the main house for the rest of his life, but the adjoining buildings had various occupants at different times, including the Louis Molteni Confectionery and Far Eastern Film Service Ltd.

At various points, two schools were also located on the premises: Royal English School and Teo Hoo Lye Institution.19 Founded in 1928 with the motto “Disce aut Discede” (Latin for “Learn or Depart”), the latter grew from an initial enrolment of about 60 boys to nearly 600 a year later.20 It was renamed Standard Institute after Teo’s death in 1933.21

Royal English School was situated on the grounds of Teo’s residence from 1924 to 1929. During this time, Teo and the school’s headmaster, Francis Neelankavil, had an acrimonious relationship and he took Neelankavil to court on two occasions over tenancy disputes, in 1926 and 1928.22

Teo was 80 when he died in November 1933, just one week after his wife.23 The Singapore Free Press reported that his funeral cortege took 45 minutes to pass on its way from Dhoby Ghaut to Bukit Brown Cemetery.24

The House of Teo Hoo Lye was acquired by Mrs Loke Yew (née Lim Cheng Kim) in 1936. Demolition works started in 1937 for the construction of Cathay Building, which was completed in 1941. Mrs Loke Yew’s son, Loke Wan Tho, had established Associated Theatres in 1935, the predecessor of Cathay Organisation.

Yap Jo Lin is an Archivist with the National Archives of Singapore. Her portfolio includes taking care of the archives’ collection of building plans.

Yap Jo Lin is an Archivist with the National Archives of Singapore. Her portfolio includes taking care of the archives’ collection of building plans.

NOTES

-

“Aw, the Tiger, is Dead,” Straits Times, 6 September 1954, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Straits New Year Honours,” Singapore Free Press, 21 March 1918, 7. (From NewspaperSG); Song Ong Siang, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore [electronic resource]: The Annotated Edition (Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company, 2020) (From NLB OverDrive); “About Life in Malaysia…,” Straits Times, 15 December 1963, 19. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Comparing two maps: Survey Department, Singapore, Land Divisions at Meyer Road, Tanjong Katong Road, Amber Road and its Surroundings, 18 April 1979, Map (From National Archives of Singapore, Accession no. SP005936); Survey Department Singapore, Singapore Road Map. Singapore South East, 1984, Map (From National Archives of Singapore, Accession no. SP006435); Peter Lee and Jennifer Chen, Rumah Baba: Life in a Peranakan House (Singapore: National Heritage Board, 1998), 31. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 305.89510595 LEE) ↩

-

Alvin Chua, “Lee Cheng Yan,” in Singapore Infopedia, National Library Board Singapore. Article published 2009. ↩

-

Lee and Chen, Rumah Baba, 27. ↩

-

Lee and Chen, Rumah Baba, 27. ↩

-

Lee Kip Lin, The Singapore House 1819-1942 (Singapore: Times Editions, 1988), 193. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 728.095957 LEE); Lee and Chen, Rumah Baba, 31. ↩

-

“Mrs Lee Choon Guan,” Straits Times, 19 December 1931, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Kwa Chong Guan, et al., Great Peranakans: Fifty Remarkable Lives, ed. Alan Chong (Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum, 2015), 134. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 305.895105957 GRE) ↩

-

Lee and Chen, Rumah Baba, 28. ↩

-

Sam King, “House that Aw Built,” Singapore Monitor, 22 April 1984, 26. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“House-warming,” Malaya Tribune, 10 September 1928, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Haw Par Jade Collection at Museum,” Straits Times, 1 January 1980, 11; Abigail Kor and Natalie Koh, “A Look at Singapore in 1960,” Business Times, 4 June 2010, 30. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Suzanne Soh, “Jade House May Be Luxury Condominium Site,” Business Times, 28 March 1990], 2; “‘Cheapest’ Apartment Costs $2.6 million,” New Paper, 23 June 1994, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Death of Mr Teo Hoo Lye,” Malaya Tribune, 16 November 1933, 9; “Mr Teo Hoo Lye Dies at 80,” Straits Times, 17 November 1933, 13. (From NewspaperSG); Song, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore, 503. ↩

-

Julian Davison, Swan & Maclaren: A Story of Singapore Architecture ([Novato]: ORO Editions; Singapore: National Archives of Singapore, 2020), 244. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 720.95957 DAV) ↩

-

“Cathay Building – Singapore’s First Skyscraper Is Opened,” in HistorySG. National Library Board Singapore. Article published April 2015. ↩

-

“Teo Hoo Lye Institution,” Malayan Saturday Post, 26 October 1929, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Page 4 Advertisements Column 3,” Malaya Tribune, 19 December 1935, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Headmaster Sued,” Straits Times, 24 February 1926, 10; “School in Peril?”Malaya Tribune, 5 December 1928, 7; “Hard-working But Unfortunate,” Straits Times, 4 November 1933, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“As I was Saying,” Singapore Free Press, 29 November 1933, 8. (From NewspaperSG); Davison, Swan & Maclaren, 244. ↩