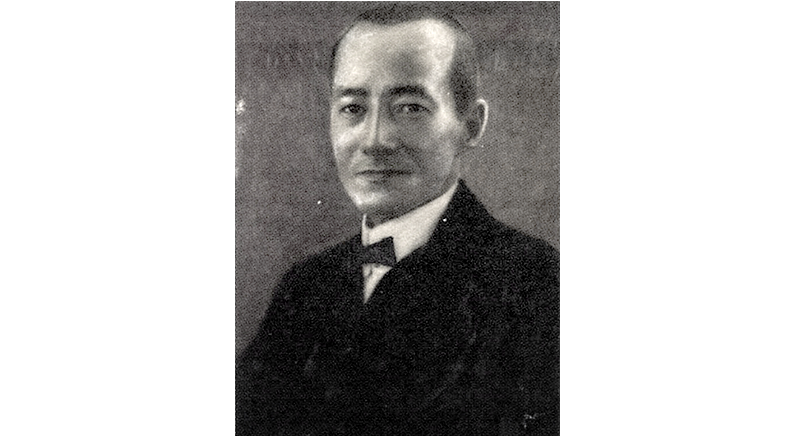

Cinema Pioneer Tan Cheng Kee

The Alhambra and Marlborough theatres were famous landmarks in pre-war Singapore. Barbara Quek looks at these cinemas, and the man behind the curtain.

Many older Singaporeans today will remember the names Runme Shaw, Run Run Shaw and Loke Wan Tho. These people were synonymous with the early cinema industry in Singapore. The two Shaws, who founded Shaw Brothers in 1925, operated major movie theatres in Singapore and were also film distributors. A decade later, Loke Wan Tho set up Associated Theatres, the forerunner of Cathay Organisation. The company also rolled out movie theatres around Singapore and made movies.

Largely forgotten though is Tan Cheng Kee, a pioneer of Singapore’s entertainment industry. Tan owned theatres that were landmarks in Singapore: the Alhambra, the Marlborough and the Palladium. (He also owned Luna Park, an amusement park adjacent to the Alhambra on Beach Road.1) Three of the six theatres listed in the newspapers in the 1920s belonged to him.2

Tan Cheng Kee’s Movie Theatre Empire

Born in 1875 in Melaka, Tan was the eldest son of Tan Keong Saik, the prominent businessman and municipal commissioner (after whom Keong Saik Road is named).3 Tan Cheng Kee’s foray into the industry began in 1909. That was the year he bought the Marlborough on Beach Road, which occupied the site of the former French Cinema owned by a Mr Joannes.4 However, it was Tan’s purchase of the Alhambra, also in 1909, that drew more attention. The Alhambra had its origins as a tent cinema at the junction of Hill Street and River Valley Road. Over the years, it moved and was renamed several times. By 1907, it was on Beach Road and was known as the Alhambra.5 Fernand Dreyfus, a Frenchman, had taken over the Alhambra from Lionel Willis, and on 8 July 1909, Tan bought the Alhambra from Dreyfus.6

Tan subsequently had the Alhambra rebuilt. In February 1914, he told the Malaya Tribune that “in a very few days the construction of the new Alhambra would be in full swing”.7 Designed by local Eurasian architect J.B. Westerhout and completed in 1916, the new theatre was described by the Malaya Tribune as “a phoenix [that had] arisen from the ashes of the old” and “Mr Tan Cheng Kee, the owner, deserve[d] every praise for his enterprise for adding another fine building to our city”.8

The newspaper reported that the Alhambra combined Eastern and Western architectural elements. “Though the two do not blend into a happy ensemble yet has this style been chosen with a view to make interior arrangements airy, and in this the architects have succeeded admirably,” the newspaper wrote. It added approvingly that on entering the place, “every modern convenience will be found, including a ladies’ cloak-room, a private telephone cabinet with writing tables, shaded lamp and chair, refreshment room and last, but not least, a spacious drawing-room”. The presumably more expensive seats were in 12 boxes in two tiers upstairs. The boxes – each “holding six comfortable carved teak chairs” – “allow a view of all present”. On the ground floor were brown wooden chairs, “each fitted with a hat rack [and] arranged [to] offer comfortable seating capacity”. There were also fans on the walls.9

This picture house by the sea boasted a gigantic cinema hall that could seat about 3,500 and a tea garden with a live orchestra to entertain before the start of the show. Cinema manager Chia Soo Ann was full of praise for the orchestra and its conductor: “Many times we were mesmerised by his swinging and swishing baton as he led his musicians through the scenes.”10

The Alhambra’s location right next to the beach gave the theatre its nickname “Hai Kee” which means “by the sea” in Hokkien. In his book, Rickshaw Reporter, George L. Peet recalled that while at the Alhambra, “we could hear the junks swaying and creaking with the tide as we watched the screen, for the windows at the back of the dress circle upstairs (where the European patrons always sat) were open to the harbour outside”.11

Tan was an ambitious man and in 1918, he acquired one of the Alhambra’s main rivals, the Palladium on Orchard Road, for $25,000. The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser reported that “the show will be under new management, and Mr Cheng Kee’s name is sufficient guarantee that it will maintain the high standard of the past”.12 In 1925, Tan remodelled the Palladium and renamed it the Pavilion.13 This cinema was demolished and replaced by Specialists’ Shopping Centre in 1971. The latter was in turn torn down for Orchard Gateway, which opened in 2014.14

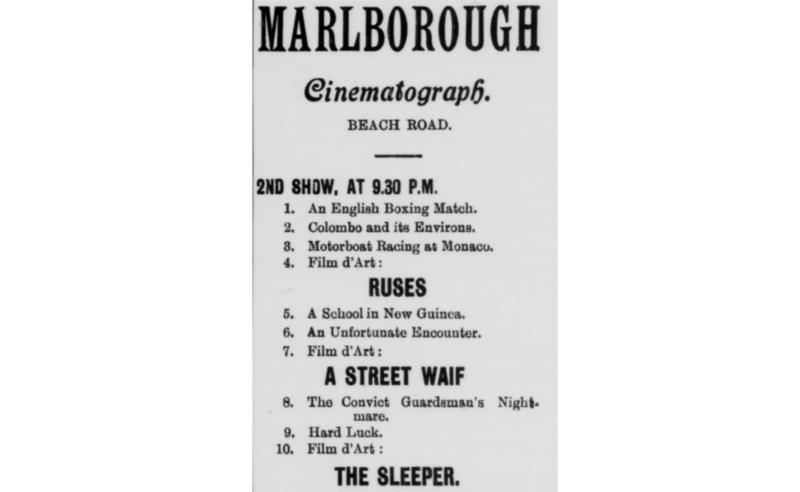

Tan believed in upgrading his cinemas. In 1918, the Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser reported that the Marlborough had been renamed the New Marlborough and “was recently rebuilt and transformed into a substantial and commodious picture palace with up to date electric fans and lighting, fitted with comfortable sitting to suit all classes of patrons”.15

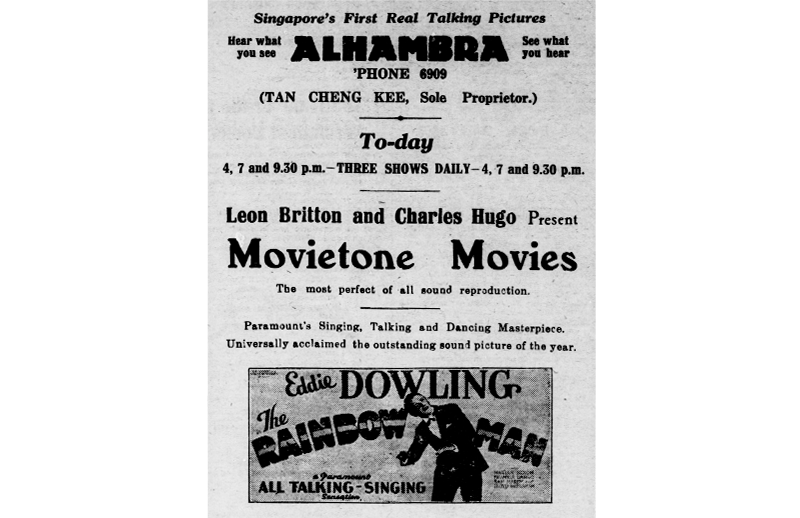

In order to accommodate “talkies” (films with sound), which were replacing silent films, Tan reportedly spent $100,000 on alterations and renovations on the Alhambra in 1930. These included insulation on the main ceiling and under the balcony, new upholstered arm seats and an increase in capacity from 800 to 1,200. Tan also announced that the Alhambra had secured screening rights from four well-known movie companies – Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, United Artists, Fox Film Corporation and Warner Brothers – for their “sound-film productions”, and that the cinema would reopen with a “talkie” screened every night, including Sundays. In November 1930, the management of the Alhambra announced a $250,000-agreement with Fox for its productions to be shown at the Alhambra from 1931–32.16

The Marlborough was also upgraded. In April 1930, the Malaya Tribune reported that the cinema hall had been rewired, the seating capacity increased from 550 to 682 and the operating room “enlarged to take in two machines, which are absolutely necessary in the case of the talkie performances, so as to ensure uninterrupted projection”.17

Tan’s management of the Alhambra came to an end when he leased out the cinema to the Shaw Brothers – which operated 60 cinemas and four amusement parks in Malaya at the time. This took effect from 1 April 1938, about a year before his death at the age of 64.

The Straits Times reported: “As the first step toward bringing the theatre back to its former status, an air-conditioning plant is being installed to make the Alhambra the first cinema in Malaya to possess such equipment. Shaw Brothers will take over control of the cinema as from April 1. During May, the building will be closed for a fortnight to enable extensive renovation and changes to be effected in interior and exterior decorations.”18

The cinema opened as the New Alhambra in July 1938, and a special feature of the air-conditioning was the specially designed rotary filter that ensured clean air in the cinema hall. Other improvements include a bar, a new box office, improved seating, a new stage and the latest architectural tubular lighting. Shaw Brothers operated the cinema until the fall of Singapore in February 1942.19

During the Japanese Occupation of Singapore (1942–45), the Japanese military appropriated the Alhambra and screened Japanese propaganda films.20

Tan Cheng Kee’s Notebooks

Not much has been written about Tan Cheng Kee, especially compared to the Shaw brothers and Loke Wan Tho. However, the National Library has three notebooks that Tan left behind as well as his will.21 These documents give an insight into the kind of person he was.

Tan believed in the importance of hard work and downplayed the role of luck. In his notebook, he wrote that “luck does not hold forever” and so a man is the “architect of his own fortune by means of his ability”. He also strongly believed that “idleness is the handmaid of the devil”.

At the same time, Tan also believed in turning to the divine for assistance. He wrote: “I feel that every step in my plan has been guided with Divine help and I hope this will continue until the end of all things” and “I ask daily for Divine help and I have succeeded beyond my dreams”.

In his notebooks, Tan devoted many pages to the importance of writing a will, pertaining to family and business. He first made his will in 1935 and appointed Estate and Trust Agencies in 1937 as the executor and trustee of his will.22 In his will, Tan ensured that his immediate and close family members had life interests in the properties that they resided in. He also bequeathed money to his uncle, cousin, clerk and cook.

.png)

What was interesting were his plans for the Alhambra and Marlborough after his death, which were bequeathed to his trustee. He instructed his trustee to “discontinue the business of a cinematograph exhibitor carried on by me” and let the Theatres “on rents to the highest bidders by tender from time to time for a period not exceeding three years each time”. This was in line with how he had leased out the cinemas to the Shaw Brothers in 1938.

He also entrusted his trustee “to use his best endeavours to secure an extension or renewal of the leases” but in the event of the Government declining to extend or renew the leases, he directed his trustee “to cause the buildings therein to be demolished before the expiration of the leases tenders being called”.23

Tan died on 12 September 1939 in his residence at 319 East Coast Road, and was laid to rest at Bukit Brown Cemetery. He left behind a son Tan Soon Lay, daughter-in-law Yeo Siok Tin, a daughter Josephine Tan, son-in-law Wee Guan Hong, and three grandchildren. His wife had died in 1927.24

In May 1947, there was a legal tussle for the sites of the Alhambra and Marlborough between the Commissioner of Land and the Executor and Trustees of the Estate of Tan Cheng Kee (deceased). Tan had obtained three leases from the government for a period of 30 years for the sites of the two cinemas, the last of which expired on 30 September 1943. The condition was that the sites should be used for show business only and could not be sublet; when the lease expired, the buildings remaining on the land would belong to the Crown.25

After the Japanese Occupation, the Executor and Trustees of the Estate continued to occupy the Alhambra and Marlborough sites under temporary occupation licences, with the condition that the land was not transferable. It was later revealed that the United Film Distributors Syndicate had been operating the cinemas without permission from the Land Office and was paying a percentage of the net takings from the cinemas to the Executor and Trustees of Tan’s estate. A notice to quit was served by the Land Office on 31 January 1947.26

In September 1947, the court ordered United Film Distributors Syndicate to quit and vacate the Alhambra and Marlborough. A new company, Singapore Amusement Syndicate, then leased the cinemas from the government and began screening films in October that year.27

The Alhambra was subsequently acquired by Cathay Organisation and opened on 5 February 1951 after a facelift.28 In December 1966, it was renamed the Gala following major renovations and a massive upgrading of the entire cinema. Earmarked for urban redevelopment, it was demolished in the late 1970s, in what was described as a “sad ending to a monumental building in the history of Singapore”.29

Shaw Towers was built on the land where the Alhambra and the Marlborough once stood. Shaw Towers itself had two cinemas: Prince and Jade. However, Shaw Towers is now being torn down as well, to be replaced by a 35-storey integrated development with offices, retail and food and beverage offerings. It is not known whether there will be a cinema or cineplex in the new development.

Barbara Quek is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She is in the team that oversees the statutory functions of the National Library Board in the compliance of Legal Deposit in Singapore. Her work involves developing the National Library’s collections through gifts and exchange as well as providing content and reference services.

Barbara Quek is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She is in the team that oversees the statutory functions of the National Library Board in the compliance of Legal Deposit in Singapore. Her work involves developing the National Library’s collections through gifts and exchange as well as providing content and reference services.NOTES

-

Gloria Chandy, “The Pioneer Cinemas,” New Nation, 19 March 1979, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Remembering Garrick,” Straits Times, 13 May 1990, 26. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Song Ong Siang, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore (London: John Murray, 1923), 222. (From BookSG); “The Late Mr. Tan Keong Saik,” Straits Times, 6 October 1909, 7; “Death of Mr. Tan Cheng Kee,” Malaya Tribune, 12 September 1939, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Thirty Years of Film Entertainment,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 2 January 1932, 20. (From NewspaperSG); Chua Ai Lin, “Cultural Consumption and Cosmopolitan Connections: Chinese Cinema Entrepreneurs in 1920s and 1930s Singapore,” in The Business of Culture: Cultural Entrepreneurs in China and Southeast Asia, 1900–65, ed. Christopher Rea and Nicolai Volland (Vancouver: UBC Press, [2015]), 209. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. 330.951 BUS) ↩

-

“The Grand Cinematograph,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 14 September 1907, 12; “Page 2 Advertisements Column 3,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 16 October 1907, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Thirty Years of Film Entertainment”; “Mountain-air Climate in Singapore,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 27 July 1938, 4; “Page 8 Advertisements Column 5,” Straits Times, 9 July 1909, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Still Another Theatre for Singapore,” Malaya Tribune, 12 February 1914, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The New Alhambra,” Malaya Tribune, 13 January 1916, 9. (From NewspaperSG); Alan Chong, ed. Great Peranakans: Fifty Remarkable Lives (Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum, 2015), 146. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 305.895105957 GRE) ↩

-

Chandy, “The Pioneer Cinemas”; Lim, Kay Tong, Cathay: 55 Years of Cinema (Singapore: Landmark Books, 1991), 72. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 791.43095957 LIM) ↩

-

George L. Peet, Rickshaw Reporter (Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 1985), 133. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 070.924 PEE) ↩

-

“The Palladium,” Malaya Tribune, 1 May 1918, 4; “Untitled,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 2 May 1918, 275. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Page 4 Advertisements Column 2,” Malaya Tribune, 2 October 1925, 4; “Page 6 Advertisements Column 1,” Straits Times, 1 December 1925, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Susanna Kulatissa, “… Not Forgotten,” Straits Times, 21 July 1985, 10; “Orchard Gateway Opens After Delay,” Straits Times, 19 April 2014, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Picture Shows,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 26 February 1918, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“‘Talkies’ Every Night,” Malaya Tribune, 11 Feb 1930, 8; “A $250,000 Deal,” Straits Times, 14 November 1930, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Marlborough Theatre,” Malaya Tribune, 19 April 1930, 8; “Talkies in Singapore,” Straits Times, 19 April 1930, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Singapore Cinema to be Air-conditioned,” Straits Times, 20 March 1938, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Air-Conditioning of the Alhambra Theatre Begun,” Straits Times, 19 June 1938, 3; “Alhambra to Reopen in October,” Singapore Free Press, 17 September 1947, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tan Cheng Kee, Tan Cheng Kee’s Notebooks (Singapore: n.p., 1912–38). (From National Library Singapore, Call no. RRARE 384.8092 TAN) ↩

-

Tan Cheng Kee, Will of Tan Cheng Kee (Singapore: n.p., 1935–39). (From National Library Singapore, Call no. RRARE 384.8092 WIL) ↩

-

Tan, Will of Tan Cheng Kee, 5. ↩

-

“Death of Mr. Tan Cheng Kee”; “Domestic Occurrences,” Malaya Tribune, 14 September 1939, 15; “Untitled,” Straits Times, 28 January 1927, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Legal Tussle Over Sites of 2 Theatres,” Malaya Tribune, 10 May 1947, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Alhambra to be Renovated,” Straits Times, 13 January 1951, 5; “Face Lift for S’pore Cinema,” Straits Times, 14 January 1951, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lim, Cathay: 55 Years of Cinema, 72; “100, Beach Road, Through the Years,” City Weekly, 19 July 1996, 2; “Gala Cinema to Open with Charity Show,” Straits Times, 21 December 1966, 24. (From NewspaperSG) ↩