Labouring to Deliver: A History of Kandang Kerbau Hospital

The old Kandang Kerbau Hospital was once known as the busiest maternity hospital in the world. Joanna Tan delivers the story behind a hallowed Singapore institution.

Singapore’s total fertility rate is a concern among policymakers today. In 2020, Singapore’s total fertility rate was just 1.1 births per woman, well below the replacement rate of 2.1.

The situation was very different five decades ago though. In the 1960s, Singapore’s total fertility rate was a staggering 5.76.1 The old Kandang Kerbau (KK) Hospital was so busy that it was nicknamed the “Birthquake” Hospital. Between the 1950s and early 1970s, more than 1.2 million babies were born there.2

In fact, in 1966 alone, 39,835 babies were born in the hospital. This earned the hospital a mention in the Guinness Book of Records for having the largest number of births in a single maternity facility – a record it held for a number of years. The publication described the hospital as the “largest maternity hospital in the world… with 316 beds and an annual ‘birthquake’ of over 26,000 babies”.3

.png)

Dr Tow Siang Hwa, who was the University Head of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in the 1960s, recalled that the hospital had to “make use of all the space available” as there were insufficient beds. He said: “Some women even had to give birth under a bed where another woman was giving birth. To cope with the serious shortage of medical facilities, women who gave birth were sent home hours later if they stopped bleeding and showed no signs of complications. Nurses then visited the mother’s home until the baby’s umbilical cord dropped.”4

The midwives were, of course, just as overwhelmed. “Last time the old KK in Labour Ward, especially night shift, is very tough,” recalled Mary Hee Sock Yin who started working at KK Hospital in 1961. “And then you keep on delivering… the patients, delivered until onto the floor. You have to put a green mat on the floor, to deliver the baby.”5 Fellow midwife Pong Siok Ing said that some deliveries were done with “patients lying on rubber macintoshes or on transport trolleys”. She said that the “babies kept coming so fast that there was no time for us to sterilise the rubber gloves in between. We had to use our bare hands.”6

Fifth General Hospital

While largely seen as a maternity hospital today, KK had its origins as Singapore’s 5th General Hospital. It began operations in 1860 with the transfer of patients from other hospitals. The hospital was divided into a section catering to the Europeans known as Seamen’s Hospital and another for locals known as Police Hospital.7 It offered gynaecology and childbirth services from as early as the 1860s.8

The hospital was located at the site bounded by Serangoon, Selegie, Bukit Timah and Rochor roads. By at least the turn of the 20th century, it had become known variously as General Hospital Kandang Kerbau or Kandang Kerbau Hospital. The term kandang kerbau means “buffalo pen” in Malay, and it is believed the hospital was so named as bullock carts belonging to the colonial transport department were parked nearby. The Chinese referred to the hospital as Tek Kah Hospital. Tek kah, or zhu jiao in Mandarin, literally means “under the bamboo trees” in Hokkien as the hospital lay beneath a hillock dotted with bamboo plants.9

Specialisation in Maternal Health

Migrants to Singapore in the 19th century were largely male. However, as more female migrants began arriving in Singapore in the first few decades of the 20th century, birth rates rapidly increased and naturally so did demand for maternity-related medical services.10

The Free Maternity Hospital on Victoria Street became overwhelmed and patients had to be turned away. With more patients than beds, KK Hospital was renovated, expanded and converted into the Free Maternity Hospital comprising three one-storey buildings. When KK Hospital officially opened as a maternity hospital on 1 October 1924, the Free Maternity Hospital on Victoria Street moved to KK Hospital.11

Later, when this new maternity hospital proved unable to meet demand, one of the buildings was torn down and a three-storey block with 120 beds was erected in 1934. However, the number of births continued increasing so rapidly that another new block was built, increasing the number of beds to 180 when it opened in July 1940. There were 6,184 births that year – all pro bono. Paying patients and gynaecological cases were treated at the General Hospital on Outram Road.12

In the pre-war years, KK Hospital was a well-regarded hospital. J.S. English, Professor of Midwifery and Gynaecology at the King Edward VII College of Medicine (1922–48) and Director of the hospital (1924–42), remarked in 1948 that “before the war… it was then one of the finest in the world… twice as large as any such hospital in England. People from all over the world who visited the Hospital were deeply impressed by the facilities and equipment we had then”.13

Post-war Baby Boom

During the Japanese Occupation of Singapore (1942–45), KK Hospital was renamed Chuo Byoin (Central Hospital) and functioned as a general hospital serving both locals and Japanese civilians. Deliveries at the hospital dipped below 2,000 each year during that period. When the Occupation ended, the hospital resumed its pre-war role of caring for women’s health. With the consolidation of all gynaecological and obstetric services at KK Hospital, it became the only maternity hospital in Singapore.14

In the immediate post-war years, population growth in Singapore accelerated and one of the contributing factors was the high fertility rate.15 In 1948 alone, KK Hospital saw 10,000 births, almost twice the number before the war, earning the description “busiest baby factory in the British Empire”. The hospital continued to handle slightly fewer than 1,000 deliveries per month until 1950 when the monthly figure rose above 1,000 babies, resulting in overcrowded labour wards.16

To address the bed shortage, the hospital made plans in 1951 for a new extension with “outpatient clinics and ancillary departments”, renovations to the existing wings and the addition of buildings to eventually increase bed capacity to 590, up from 240.17

Construction of the new extension began in 1953, but births continued to climb sharply with a new baby born every 10 minutes. As described in a 1953 Straits Times article: “[T]he Kandang Kerbau… last year dealt with over 17,000 maternity cases, and a total of over 20,000 admissions in its 240 beds. For what the record is worth, Singapore can claim to have the busiest and most overcrowded maternity hospital in the world today. London’s famous Queen Charlotte’s maternity hospital deals with 3,000 births a year. At Kandang Kerbau five times as many babies are born, nearly a third of the total born in the Colony.”18

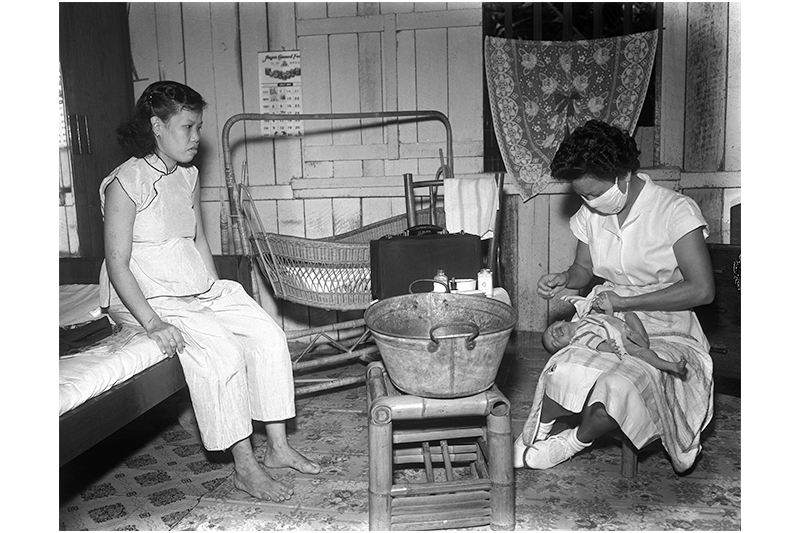

A number of measures were introduced in the 1950s to ease the hospital’s burden. In 1950, the length of hospital stay for each patient was reduced from 10–12 days to three days. Midwives from the hospital’s Domiciliary Aftercare Service, introduced in 1954, visited mothers who had been discharged 24 hours after confinement, and their babies, at home. They would report any abnormality to the hospital for follow-up action.19

In October 1953, then Governor of Singapore John Nicoll endorsed the idea of home births.20 Under this policy, women with a normal prenatal examination could give birth at home if their home environment was conducive, and the Domiciliary Delivery Service was introduced in 1955 for this purpose.21 Women who had received prenatal care at the hospital were offered the choice of home delivery. Staff then visited the women’s home to assess its suitability for home birthing.22

World’s Busiest Maternity Hospital

KK Hospital’s new extension finally opened in August 1955, but the bed capacity still fell far short of the numbers needed to keep up with demand. Deliveries in 1956 and 1957 were a staggering 25,000 and 29,000 respectively, double the figure in 1951.23 In 1958, there were about 110 births per day at the hospital, or more than 40,000 a year, according to Minister for Health A.J. Braga.24 The number of babies born there continued to increase well into the 1960s.

Dr Yvonne Marjorie Salmon, a long-serving obstetrician-gynaecologist who spent 44 years at KK Hospital, recounted her experience during the “birthquake” in 1966 when 39,856 babies were born. She said: “[T]here were so many born, 100–140 per day, that we could hardly cope. It was like a war zone, with emergency beds placed in the corridors and mothers delivering on the theatre trolleys and mattresses on the floor. There were so many deliveries that postnatal mothers sometimes had to lie crosswise, three to two beds (a record for neighbourliness).”25

The baby boom continued unabated until the effects of the national family planning campaign, launched in 1960, were felt when the total fertility rate dropped to 3.07 in 1970, down from 3.22 in 1969.26 In 1970, for the first time, deliveries at KK Hospital dipped below 30,000. Other government hospitals like Alexandra Hospital as well as private hospitals also started to take on some maternity patients, relieving KK Hospital of its caseload.27

Training and Education

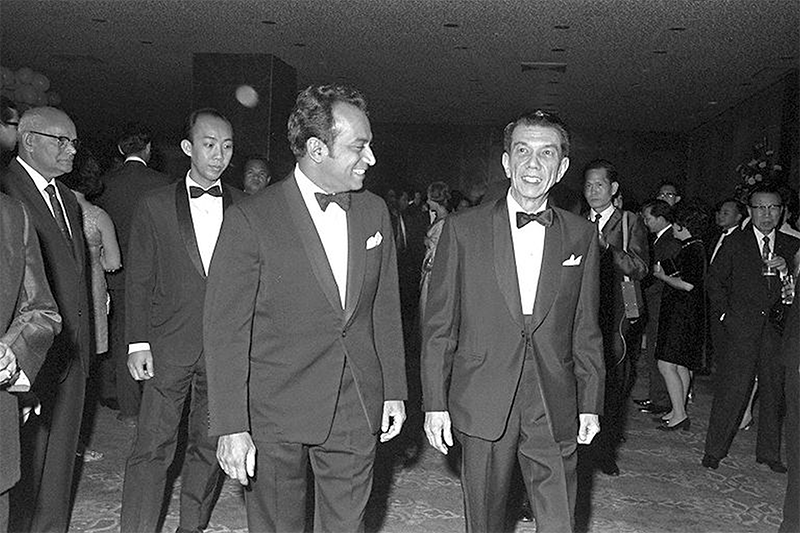

In addition to providing maternity services, KK Hospital also provided final year medical students with intensive training that included a three-month stay on the hospital’s premises.28 Among those who underwent training at the hospital was the second president of Singapore, Dr Benjamin Henry Sheares (he served from 1971 until his death in 1981).29

Sheares succeeded J.S. English as Acting Professor of Midwifery and Gynaecology at the King Edward VII College of Medicine when the latter retired in 1948. (In 1951, Sheares was appointed Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at the University of Malaya; the first local to assume this post.)30 Like English, Sheares sought to improve maternal mortality and still-birth rates. Among his proposals were the implementation of a post-graduate course in obstetrics and gynaecology at the King Edward VII College of Medicine, with the doctors receiving their training at KK Hospital.31 He also raised the standard of midwives, who now needed to have at least a primary English education and two years of training in a teaching hospital.32

Salmon, who had teaching duties at the hospital, said that the hospital in the 1960s provided good training for the staff: “As the ‘C’ Class (heavily subsidised) beds catering for the lower social classes were always fully occupied, the young doctors, medical students and nurses/pupil midwives had more practical experience compared with the present time.”33

When KK Hospital was reorganised in 1962 comprising a University Training Unit and two Clinical Training Units, it was recognised and accredited by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) in London as a post-graduate training centre for aspiring gynaecologists.34 This was a significant achievement as it meant that specialty training could be done locally instead of in the United Kingdom.

One of the first few doctors who received his training entirely in Singapore was Professor S.S. Ratnam (Shanmugaratnam s/o Sittampalam), who later headed the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecoloy at KK Hospital and then at the National University of Singapore. Ratnam recalled that he and his fellow doctors were initially afraid of failing the Member of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (MRCOG) examinations in the UK, but most passed the examinations on their first attempt.35

Medical Breakthroughs

Doctors at KK Hospital also contributed to medical research. In the 1950s, as Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the University of Malaya’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at KK Hospital, Sheares invented a procedure known internationally as “Sheares Vaginoplasty” or “Sheares Operation” that created an artificial vagina for girls born without one.

“This new procedure was the result of my work in the early post-war years when quite a few women came to me with undeveloped vaginas and I carried out the operation as it was practised then but felt it was not right. I thought it out and developed my own procedure,” said Sheares. His procedure was described as “safer, more efficient and having better results than the traditional method”. A woman who underwent this procedure successfully delivered a seven-pound (3.2 kg) baby naturally in 1954 and subsequently a second child as well.36

Sheares was also credited for being the first to perform caesarean sections using the lower segment method when he was Assistant Superintendent of KK Hospital during the Japanese Occupation.37 This modern lower method minimised complications that could arise during surgery, resulting in a scar that was also stronger and better able to withstand future pregnancies.

“Under the old professor very few caesarean sections were carried out and they were all done by the classical method and not the modern lower segment method,” Sheares recalled. “I had to continue doing what I knew was not right. I tried to keep up with the times by reading journals but could not do what I wanted at all. Those were frustrating and heartbreaking years because I knew I was killing babies unnecessarily when they could have easily been saved by the lower segment caesarean section.” For his contributions, Sheares is known as the “father of obstetrics and gynaecology in Singapore”.38

Another surgeon from KK Hospital who left his mark was Professor S.S. Ratnam. On 19 May 1983, Ratnam and his team delivered Asia’s first “test-tube baby”, a baby conceived through in-vitro fertilisation, at KK Hospital. Three years later, he and his team of doctors also helped to deliver the first baby in Asia born from gamete intrafallopian transfer (GIFT), which involves a direct transfer of the sperm and egg into the fallopian tube.

Ratnam was very proud of Singapore’s contributions to the field of obstetrics and gynaecology. He said: “We had a number of firsts… the first in Asia IVF baby… the first GIFT baby born in Asia… the first in the world to be successful with micro-injection of sperms direct into the egg… We have made contributions not only to ourselves here, but to the world… Doesn’t matter from which unit or institution the work comes from, but in Singapore.”39

A New Beginning

In 1997, KK Hospital moved into its new building at 100 Bukit Timah Road and was renamed KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, offering more facilities and better services to meet changing health demands. Paediatric medical services were also introduced.

KK Hospital continues to strive for excellence and innovation in women’s and children’s health services. The old Kandang Kerbau Hospital, where millions of children were born, has been designated a historic site by the National Heritage Board.40

Joanna Tan is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, and works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia Collection. Her responsibilities include collection management and content development as well as providing reference and research services.

Joanna Tan is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, and works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia Collection. Her responsibilities include collection management and content development as well as providing reference and research services.NOTES

-

“Births and Fertility, Annual,” data.gov.sg, last updated 18 July 2020, https://data.gov.sg/dataset/births-and-fertility-annual; Chew Hui Min, “Singapore’s Total Fertility Rate Falls to Historic Low in 2020,” Channel NewsAsia, 26 February 2021, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/singapore-total-fertility-rate-tfr-falls-historic-low-2020-baby-376711; “Population Trends Overview,” National Population and Talent Division, last updated 14 January 2022, https://www.population.gov.sg/our-population/population-trends/overview. ↩

-

Lea Wee, “A New KK, But Keep the Little Ones Coming,” Straits Times, 29 September 1996, 2; Danny Lim, “He’s Been Through a Birthquake,” New Paper, 23 August 1997, 14; Arlina Arshad, “Old KK Hospital Now a Historic Site,” Straits Times, 24 March 2003, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Low Mei Mei, “Birthplace of Many Beside a Bamboo Grove,” Straits Times, 24 March 1987, 16. (From NewspaperSG); Tan Kok Hian and Tay Eng Hseon, eds., The History of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in Singapore (Singapore: Obstetrical & Gynaecological Society of Singapore and the National Heritage Board, 2003), 49. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING q618.095957 HIS) ↩

-

Lim, “He’s Been Through a Birthquake.” ↩

-

Mary Hee Sock Yin, oral history interview by Patricia Lee, 20 September 1999, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 3 of 11. (From National Archives of Singapore, Accession no. 002206) ↩

-

Tan and Tay, The History of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in Singapore, 53. ↩

-

Singapore General Hospital (Singapore), Singapore General Hospital: 50th Anniversary Publication 1926–1976 (Singapore: Singapore General Hospital, 1976), 50. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 362.11095957 SIN) ↩

-

Arlina Arshad, “Old KK Hospital Now a Historic Site”; Wee, “A New KK, But Keep the Little Ones Coming.” ↩

-

Saw Swee Hock, “Population Trends in Singapore, 1819–1967,” Journal of Southeast Asian History 10, no. 1 (1969): 36–49. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); Tan and Tay, The History of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in Singapore, 6. ↩

-

Colin Cheong, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital: 150 Years of Caring 1858–2008 (Singapore: KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, 2008), 25. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 362.19820095957 KK); Medical Department (Singapore), Annual Report of the Medical Department (Singapore: Medical Department, 1947), 37, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/b31414989/page/36/mode/2up. ↩

-

Benjamin Henry Sheares, “Speech by President Sheares at the Kandang Kerbau Hospital Recreation Club Dinner and Ball on Saturday: 23rd November 1974 at the Hyatt Hotel at 8 p.m,” 23 November 1974, transcript (From National Archives of Singapore, Document no. PressR19741123) ↩

-

“Delivered 82,000 of ‘Em But Says I Still Don’t Know About Babies,” Malaya Tribune, 18 March 1948, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tan and Tay, The History of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in Singapore, 50, 63; “KKH Milestones,” Straits Times, 20 November 2002, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Saw, “Population Trends in Singapore, 1819–1967,” 40. ↩

-

Cheong, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, 33, 46. ↩

-

Cheong, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, 50; Medical Department (Singapore), Annual Report of the Medical Department (Singapore: Medical Department, 1951), 164, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/b31415027/page/166/mode/2up. ↩

-

“Ten Minute Babies,” Straits Times, 8 October 1953, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tan and Tay, The History of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in Singapore, 373; SingHealth Group, “Milestones and Achievements,” KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, last updated 3 March 2021, https://www.kkh.com.sg/about-kkh/corporate-profile/hospital-milestones. ↩

-

“Nicoll Backs Home Births Policy,” Straits Times, 7 October 1953, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tan and Tay, The History of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in Singapore, 64 ↩

-

Cheong, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, 52. ↩

-

Tan and Tay, The History of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in Singapore, 64. ↩

-

“Home Midwifery Plan to Ease Crowding,” Straits Times, 28 September 1958, 4. (From NewpaperSG) ↩

-

Tan and Tay, The History of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in Singapore, 492; Arlina Arshad, “Old KK Hospital Now a Historic Site.” ↩

-

“Births and Fertility, Annual”; Family Planning in Singapore (Singapore: Govt. Printer, 1966), 3. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 363.96095957 FAM) ↩

-

Kandang Kerbau Hospital (Singapore), Kandang Kerbau Hospital 1924–1990, 25. ↩

-

“Thousands of Babies Work of Maternity Hospital,” Straits Times, 15 July 1941, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Wong Kim Hoh, “Helping Babes into the World,” Straits Times, 13 November 2010, 8. (From NewspaperSG); Tan and Tay, The History of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in Singapore, 472. ↩

-

J.H.H. Sheares, “Benjamin Henry Sheares, MD, MS, FRCOG: President, Republic of Singapore 1971–1981; Obstetrician and Gynaecologist 1931–1981. A Biography, 12th August 1907–12th May 1981,” Annals 34, no. 6 (2005): 25C–41C, Academy of Medicine, Singapore, http://www.annals.edu.sg/pdf/34VolNo6200506/V34N6p25C.pdf. ↩

-

Tan and Tay, The History of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in Singapore, 418. ↩

-

Kandang Kerbau Hospital (Singapore), Kandang Kerbau Hospital 1924–1990, 18; Tan and Tay, The History of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in Singapore, 418. ↩

-

Tan and Tay, The History of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in Singapore, 493. ↩

-

SingHealth Group, “Milestones and Achievements”; Ministry of Health (Singapore), Report of the Ministry of Health (Singapore: Ministry of Health, 1962), 163, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/b31415714/page/152/mode/2up. ↩

-

Ratnam, S S (Prof.) @ Shanmugaratnam s/o Sittampalam, oral history interview by Soh Eng Khim, 19 September 1997, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 7 of 13. (From National Archives of Singapore, Accession no. 001936); Kandang Kerbau Hospital (Singapore), Kandang Kerbau Hospital 1924–1990, 18. ↩

-

“Sheares: They Call Him the Father of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in Singapore,” New Nation, 28 April 1976, 10–11. (From NewspaperSG); Cheong, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, 66. ↩

-

Cheong, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, 38. ↩

-

“Sheares: They Call Him the Father of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in Singapore”; Tan and Tay, The History of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in Singapore, 416. ↩

-

Cheong, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, 130; Tan and Tay, The History of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in Singapore, 568. ↩

-

SingHealth Group, “Milestones and Achievements”; Arlina Arshad, “Old KK Hospital Now a Historic Site.” ↩