Giving a Voice to the Dead: Remembering Chao Tzee Cheng

As a forensic pathologist, Chao Tzee Cheng helped bring murderers to justice.

By Goh Lee Kim

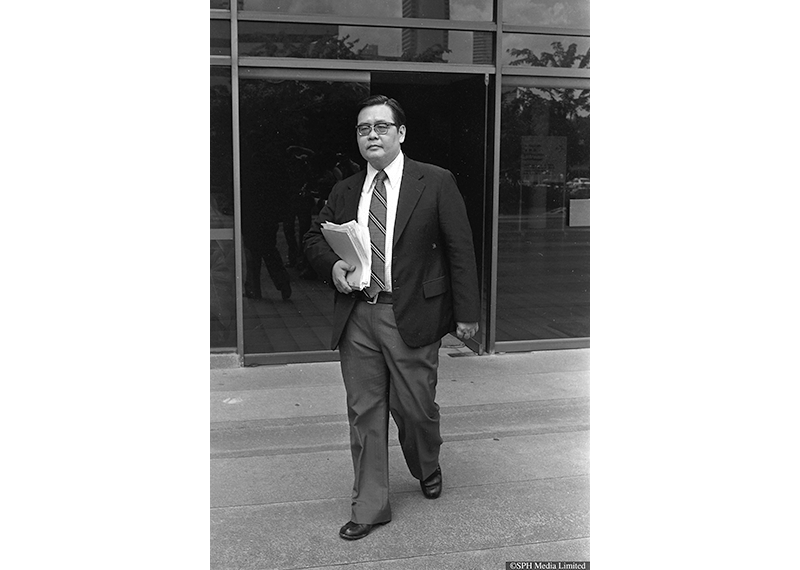

Most people shy away from facing the aftermath of violent deaths. Fortunately for Singapore, however, the late Professor Chao Tzee Cheng was not like most people. Over the course of a career spanning more than 30 years, he would help ensure that justice was served.1

During that time, Chao played a pivotal role in raising the standards of forensic medicine, both in Singapore and the region. Along the way, he worked on some of the most high-profile crimes and mass disasters in Singapore.

Blazing the Trail in Forensic Pathology

Chao became a forensic pathologist by accident, literally. After completing his medical degree at Hong Kong University in 1961, he returned to Singapore where he had initially aimed to specialise in surgery.2 However, while on honeymoon in Johor, the car that he and his wife were travelling in plunged into a ravine. The accident put him in a week-long coma and also weakened his right hand. This dashed his hopes of becoming a surgeon.3 Undaunted, Chao trained himself to use his left hand and set his sights on pathology instead.

In 1966, Chao left for Hammersmith Hospital in London to obtain a diploma in clinical pathology under a one-year Colombo Plan Scholarship. His boss back in Singapore suggested that he specialise in forensic pathology and as a result, Chao’s scholarship was extended by another year and a half so that he could obtain his diplomas in forensic pathology and medical jurisprudence.

Chao returned to Singapore in 1969 where he established the first dedicated forensic pathology section within the Department of Pathology at Singapore General Hospital. Two years later, he was appointed to the position of Forensic Pathologist.

Before Chao, there were no professionally trained forensic pathologists in Singapore. In an oral history interview, he recalled that Coroner’s cases used to be handled by ordinary pathologists with no specialised training. As a result, standards varied from person to person. Upon his return to Singapore, Chao revamped the entire system. Under his watch, forensic pathologists began visiting crime scenes as a matter of course. Prior to that, pathologists would simply examine dead bodies in the mortuary. “One by one, you just carry on the work, finish the post-mortem and give a report and that’s all. But I thought there is much more than that,” he said.4

Solving Unnatural and Violent Deaths

Chao’s work as a forensic pathologist involved conducting autopsies in cases of sudden, unnatural or violent deaths, using his forensic skills to reconstruct the cause of death and give the dead a voice.

In a piece penned for the Law Gazette after Chao’s death in 2000, Clinical Professor Chee Yam Cheng, Master of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, wrote that Chao had “the knowledge of a medical doctor, the sharp eyes and instinct of Sherlock Holmes, and the oratorical skills and confidence of a lawyer in court”.5

“[S]ometimes, in murder cases, the accused always gives you a story that is advantageous to themselves,” Chao had said, “but you got to prove that they are wrong… by… what we called the ‘silent’ witnesses… all the trace evidence that is on the scene, the injuries that the deceased person, the victim has and so on… we got to build up from all these evidence to prove that the story is not correct. And we have done that many, many times.”6

Chao was put to the test in his first case after his return from London when he testified in the trial of Ng Yio Gee in 1970. Ng was accused of killing his fiancée, Lim Aye Siok. Not only did Chao have to interpret another pathologist’s findings without conducting the autopsy personally, he was also a rookie who had yet to make his mark then.

While it appeared to be a classic case of drowning, Chao determined the cause of death as strangulation due to the butterfly-shaped bruises on Lim’s neck. He also cited new research, which showed that the frothing in her mouth could be the result of strangulation. This contrasted with the findings from the original pathologist as well as Ng’s claim of a double suicide. Later, aware that his testimony would not square with Chao’s findings, Ng admitted to lying about the suicide pact and was eventually found guilty of causing grievous hurt.7

Chao subsequently worked on some challenging cases, such as that of K. Rajendran in 1972. Rajendran had been assaulted and his body laid across railway tracks to make his death look like a suicide or accident.8 In 1985, Chao’s testimony also helped convict Michael Tan and his accomplice in the murder of Tan’s landlady and her two children. Tan claimed to have stabbed her by accident, but this account was disproven in court by Chao.9 In 1995, he was also involved in the high-profile case of Briton John Martin Scripps, a skilled butcher, who was convicted of murdering and dismembering South African tourist Gerard George Lowe.10

The late criminal lawyer Subhas Anandan recalled that Chao once saved a man from the gallows even though Chao was testifying for the prosecution. “Only once, in all these years, did he ever agree with my arguments, and I got a murder charge reduced,” said the veteran lawyer who had known Chao since 1971. “[E]very time I heard he was going to be called up for my cases, I would go, ‘Alamak! Not this fella again!’”11

Anandan was likely referring to the trial of Karnan Arumugam for the death of brothel caretaker Lim Kar Teck in 1992. Arumugam’s murder charge was reduced to wrongful confinement and causing grievous hurt after the judge agreed with Chao that Lim’s suffocation due to gagging was “fortuitous” as gagging was “seldom intentionally homicidal” and not necessarily fatal.12

One of Chao’s most best-known cases concerned Filipino domestic helper Flor Contemplacion, who was hanged in Singapore in 1995 for the murder of fellow domestic helper, Della Maga, and her young charge, Nicholas Huang. The Philippines National Bureau of Investigation had disputed the findings of Singapore’s Institute of Science and Forensic Medicine (ISFM) that Maga had been strangled. Instead, they alleged that her body showed signs of a savage beating inflicted by a man. This case attracted intense attention in the Philippines, and there were widespread protests in the country that threatened bilateral relations.13 In the face of overwhelming pressure and scrutiny, Chao stood firmly by the ISFM’s findings. ISFM was eventually exonerated when two independent panels of experts corroborated Singapore’s findings.14

Chao was often invited by other countries to consult in difficult cases. These included the Ipoh loh shee fun (rice noodles) food poisoning incident in 1998 in which noodles contaminated with aflatoxin claimed 14 lives.15 He also helped with the 1984 inquiry into the death of Ponniah Rajaratnam, a retired Singaporean Deputy Commissioner of Police and former Director of the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau. Rajaratnam was then heading Brunei’s Anti-Corruption Bureau, and it was alleged that he had been kidnapped and strangled while in Brunei. However, Chao determined that Rajaratnam died of drowning and no foul play was suspected.16

Investigating Mass Disasters

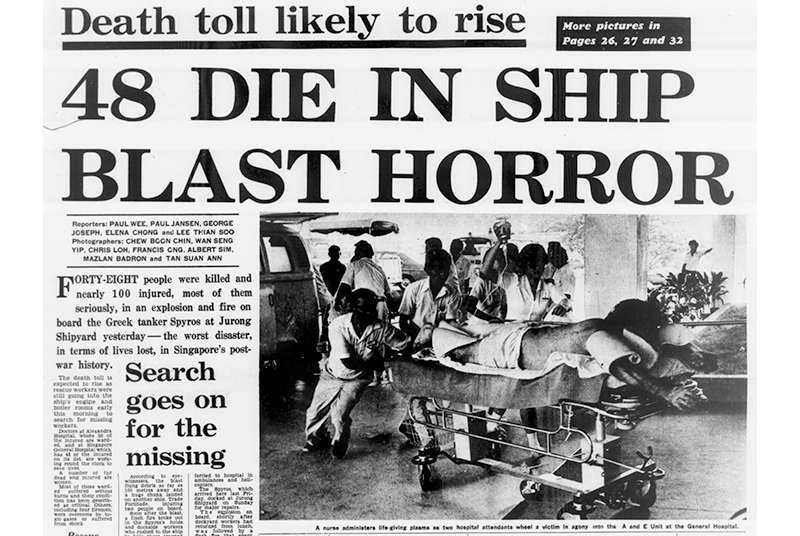

Along with criminal cases, Chao was also reputed for his forensic prowess in investigating some of the worst disasters in the modern history of Singapore. These include the explosion on board Greek oil tanker S.T. Spyros in 1978, the Sentosa Cable Car tragedy in 1983, the collapse of Hotel New World in 1986, the explosion at Ginza Plaza in 1992 and the crash of SilkAir Flight 185 in 1997.17

In a time before DNA analysis was possible, Chao and his forensics team often worked round the clock to identify the large number of dead bodies, which were often ravaged beyond recognition.

Senwan Jamal, Senior Medical Technologist at the Department of Pathology, Singapore General Hospital, recalled his experience working with Chao on the Hotel New World disaster: “[T]he bodies from Hotel New World came in a trickle because of the demanding rescue work. In the end, it was not 100 bodies, but about 33. Even then I remember our supervisor Prof Chao Tzee Cheng’s quick thinking. It was in the 1980s and we were using film cameras. With so many bodies, we needed to be fast and could not wait for the photos to be developed, so he told us to buy two Polaroid cameras from Chinatown, using his own money, so that we could photograph the bodies right away.”18

The Spyros incident on 12 October 1978 was described as the “worst peace-time disaster in Singapore”, killing 76 people and injuring 69 others.19 Chao was instrumental in bringing to light how the explosion had occurred.

He began to sort the dead into groups, based on how they died. Some had severe burns, while others had less severe burns or died from carbon monoxide poisoning. “So from then, I plotted the position on the plan [of the Spyros] and found that actually you can trace the path of fire. [T]hose in the direct path of fire would be burned very severely, those outside would be less… we went to the scene and found out [that] the origin of the fire was from the fuel tank,” explained Chao.20

Advocating Safety

Because of his work, safety was an issue close to Chao’s heart, and he often emphasised the importance of accident prevention. As Deputy Chairman of the Home Safety Committee of the National Safety First Council (NSFC), Chao actively advocated for safety through studies, videos and campaigns in Singapore, particularly those concerning home accidents.21

“It grieves me to know there is more than one case of people getting burnt or scalded every day and 40 per cent of these cases involve people below the age of 11,” he said in a 1986 interview when his book, How to Prevent Home Accidents, was launched.22

Chao also devoted time to other safety initiatives. He was a member of the Toy Safety Authority of Singapore23 and helped form the Venom and Toxin Research Group in 1985.24 In the 1980s, he supported an awareness drive on the dangers of lightning.25

Chao also helped to usher in new regulations to save lives. In the course of his work, he uncovered a defect in a brand of gas water heater that resulted in the deaths of seven people between 1965 and 1974. They had died because the defect caused a build-up of carbon monoxide in poorly ventilated rooms. That particular brand was subsequently recalled and new regulations were implemented to ensure adequate ventilation in homes.26

Chao’s report on road traffic deaths between 1969 and 1973 also prompted the NSFC to recommend a compulsory medical test for suspected drunk drivers in 1974, which consequently led to the Road Traffic (Amendment) Bill of 1976.27

Honouring and Remembering

In addition to his regular work as a forensic pathologist, Chao also taught generations of medical professionals as well as helmed local and international medical associations. He was president of the Indo-Pacific Association of Law, Medicine and Science between 1983 and 1992, and he proposed the establishment of Singapore’s Medico-Legal Society in 1972.28 Awards he received include the Public Administration Meritorious Service Medal in 1995 for the Flor Contemplacion case and the Singapore Medical Association Honorary Membership, its highest honour, in 1998.29

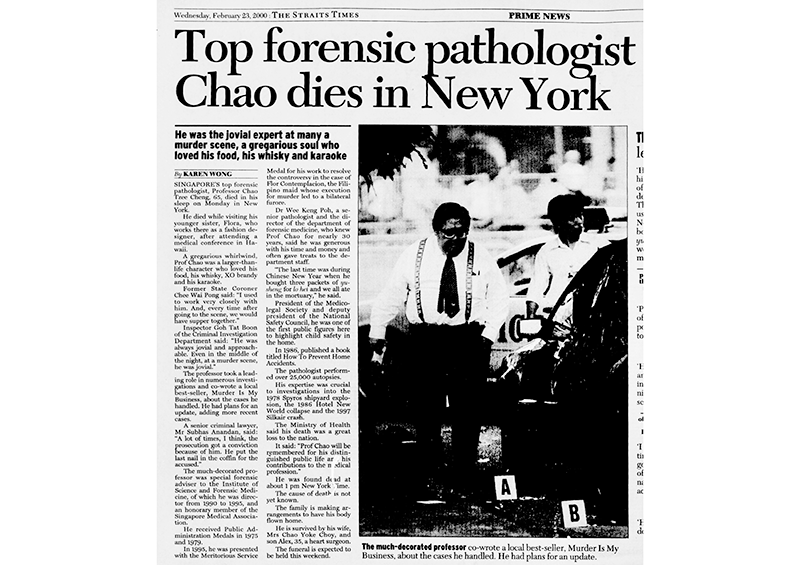

While Chao’s work was undoubtedly morbid, he did not let that define him. Chao was a charismatic man known for his wit, joviality and larger-than-life personality, and one who enjoyed various interests and hobbies. His love for singing had bagged him numerous trophies in competitions, such that he was even called the “Pavarotti of the Medical Alumni Karaoke” because he could sing in Italian.30

Chao was also a connoisseur of good food and drink, especially fine whisky and XO brandy, hence his other nickname, “Fat Chao”, among his friends.31 Even after having visited the mortuary or a crime scene, he could still eat without feeling queasy. He even admitted to taking his meals in the mortuary. “Well of course you have to! For instance, when Spyros happened, we had 76 bodies all at once! You can’t go home!”32

In 1999, Chao co-authored Murder Is My Business: Medical Investigations into Crime – a book based on his better-known cases – with journalist Audrey Perera.33

Chao reached the pinnacle of his career when he was appointed head of the Institute of Science and Forensic Medicine.34 Even after his retirement in 1997, Chao continued to serve tirelessly as the institute’s Special Forensic Advisor until his sudden demise due to heart disease while visiting his sister in New York in February 2000.35 Such were Chao’s accomplishments and reputation that after his death, accolades and tributes poured in far and wide from friends, colleagues and those who knew him.36

In his eulogy, Chao’s nephew Dr Wong Chiang Yin, who was also the Honorary Secretary (37th to 40th Councils) of the Singapore Medical Association, noted: “[T]he job does not make a man great; it is the substance of the man that fills and defines the post. For all intents and purposes [Prof Chao] was [the forensic medical practice] of Singapore.”37

Goh Lee Kim is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She is part of the team that curates and promotes access to the library’s digital collections.

Goh Lee Kim is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She is part of the team that curates and promotes access to the library’s digital collections.Notes

-

Sng Ewe Hui Jimmy, The Science of Medical Detection: 100 Years of Pathology, 1903–2003 (Singapore: Department of Pathology, Singapore General Hospital, 2003), 52, 85. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING q616.0095957 SNG) ↩

-

Chao Tzee Cheng, oral history interview by Lee Liang Chian, 14 October 1995, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 7, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 001573), 1–5. ↩

-

Chao Tzee Cheng, oral history interview, 14 Oct 1995, Reel/Disc 1 of 7, 8–10. ↩

-

Chao Tzee Cheng, interview, 14 Oct 1995, Reel/Disc 1 of 7, 13–14. ↩

-

Gregory Vijayendran, “Dead Men do Tell Tales,” Law Gazette: An Official Publication of the Law Society of Singapore, June 2000, https://v1.lawgazette.com.sg/2000-6/focus2.htm. ↩

-

Chao Tzee Cheng, interview, 14 Oct 1995, Reel/Disc 2 of 7, 27. ↩

-

Chao Tzee Cheng and Audrey Perera, Murder Is My Business: Medical Investigations into Crime (Singapore: Landmark Books, 1999), 17–26. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 364.152095957 CHA); T.F. Hwang, “Fiancee Murder Trial: Defence Surprised,” Straits Times, 21 March 1970, 4; “The Case of the ‘Butterfly’ Death,” New Paper, 5 March 2000, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chao and Perera, Murder Is My Business, 94–106; “Injuries Made a Doctor Suspect Foul Play,” Straits Times, 18 July 1972, 17. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chao and Perera, Murder Is My Business, 44–53; Sit Yin Fong, “Two Get Death for Killing Mum, Kids,” Singapore Monitor, 10 April 1985, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tan Ooi Boon, Body Parts: A British Serial Killer in Singapore (Singapore: Times Book International, 1996), 14–15, 147–150. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 364.1523095957 TAN); Chao and Perera, Murder Is My Business, 132–146. ↩

-

Ernest Luis, “Doctor Who Learned From the Dead,” New Paper, 5 March 2000, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Man Escapes Death After Murder Charge Is Reduced,” Straits Times, 16 October 1992, 31. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Flor Contemplacion: Facts of the Case (Singapore: Ministry of Information and the Arts, 1995), 14–15. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 364.1523095957 FLO); “Singapore Medical Experts Dispute Manila Findings,” Straits Times, 1 April 1995, 20; Zuraidah Ibrahim, “Singapore Pathologists ‘100 Per Cent Correct’,” Straits Times, 15 July 1995, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Flor Contemplacion, 14–15; “Singapore Medical Experts Dispute Manila Findings”; Zuraidah Ibrahim, “Singapore Pathologists ‘100 Per Cent Correct’.” ↩

-

Yaw Yen Chong, “S’pore Experts in Ipoh to Help Probe Poison Deaths,” Straits Times, 26 October 1988, 40; Yaw Yan Chong, “Poisoning of Liver the Cause,” Straits Times, 28 October 1988, 17; “Aflatoxin Likely Cause of Seven Deaths in Perak,” Straits Times, 31 May 1989, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Elena Chong, “‘Alive When He Entered the Water’,” Straits Times, 12 September 1984, 12; Elena Chong, “Coroner: No Foul Play in Ex-CPIB Man’s Death,” Straits Times, 23 September 1984, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Eight of Nine Who Died Could Have Been Saved,” Straits Times, 6 February 1974, 8. (From NewspaperSG); Chee Yam Cheng, “Citation of 1998 SMA Honorary Membership, Prof Chao Tzee Cheng,” SMA News 30, no. 5 (1998), https://www.sma.org.sg/sma_news/3005/news/3005n7.htm; Committee of Inquiry, Report on the Explosion at Ginza Plaza (Singapore: Subordinate Courts, 1993), 1, 164. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 363.11969095957 SIN); Karamjit Kaur, “Three Passengers Identified from Ring, Hair and Fingerprint,” Straits Times, 6 January 1998, 29. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ministry of Health Singapore, Caring for Our People: 50 Years of Healthcare in Singapore (Singapore: MOH Holdings Pte Ltd, 2015), 116–17, https://www.mohh.com.sg/Documents/book/caring-for-our-people-50-years-of-healthcare-in-singapore.pdf. ↩

-

“Spyros Last Major Tanker Blast CID Investigated,” New Paper, 16 March 1990, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chao Tzee Cheng, interview, 14 Nov 1995, Reel/Disc 6 of 7, 88. ↩

-

“Beware the Killers in Your Home,” New Nation, 30 August 1975, 18/19. (From NewspaperSG); National Safety First Council of Singapore, 10th Anniversary Souvenir Magazine, 1966–1976 (Singapore: The Council, 1976), 87–100. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 614.80605957 NAT) ↩

-

Yeo Kim Seng, “Prof Chao: ‘My Heart Bleeds…’,” Straits Times, 26 July 1986, 2. (From NewspaperSG); Chao Tzee Cheng, How to Prevent Home Accidents (Singapore: Federal Publications, 1986), 1–3. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 614.853 CHA) ↩

-

“‘Magic Egg’ Could Spell Danger If Swallowed,” Singapore Monitor, 17 February 1984, 6. (From NewspaperSG); Chan Chee Seng, “Speech by Mr Chan Chee Seng, Senior Parliamentary Secretary (Trade and Industry), and Member of Parliament for Jalan Besar, at the Official Inauguration of the Toy Safety Authority of Singapore (TSAS) at Shangri-La Hotel on 24 March ’82 at 12.00 Noon,” transcript. (From National Archives of Singapore, document no. ccs19820324s) ↩

-

Chua Chin Chye, “What to Do When Bitten,” Straits Times, 15 August 1986, 25; “The Pong Pong and Other Forbidden Fruit,” Straits Times, 17 November 1986, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

T.C. Chao, J.E. Pakiam and J. Chia, “A Study of Lightning Deaths in Singapore,” Singapore Medical Journal 22, no. 3 (1981): 150–57, http://smj.sma.org.sg/2203/2203smj10.pdf; “Stay Safe When It Rains,” Straits Times, 21 November 1982, 6; David Miller, “Greater Chance of Being Struck by Lightning in S’pore,” Straits Times, 2 August 1993, 24. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“PUB’s Safety Ruling on Gas Heaters,” Straits Times, 1 December 1975, 15. (From NewspaperSG); Chao Tzee Cheng, “Forensic Medicine in Singapore,” The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology 9, no. 2 (1988): 179–81, https://journals.lww.com/amjforensicmedicine/Citation/1988/06000/Forensic_Medicine_in_Singapore.19.aspx; Seah Han Cheow and Chao Tzee Cheng, “Carbon Monoxide Poisoning in Singapore,” Singapore Medical Journal 16, no. 3 (1975): 174–76, http://smj.sma.org.sg/1603/1603smj3.pdf. ↩

-

Leslie Fong, “Move to Curb Drunken Driving,” Straits Times, 8 November 1974, 1; “Drinking and Driving: The Real Danger,” Straits Times, 11 August 1975, 11; “Drunken Driving Arrests: Now Blood Test Is Obligatory,” Straits Times, 26 March 1976, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chao Tzee Cheng, 14 Oct 1995, Reel/Disc 1 of 7; Christina Cheang, “Move to Form a Society for Lawyers, Doctors,” Straits Times, 19 May 1972, 19. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chee, “Citation of 1998 SMA Honorary Membership, Prof Chao Tzee Cheng.” ↩

-

Lingam Ponnampalam, “Joker, Eater, Singer…,” New Paper, 23 February 2000, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ponnampalam, “Joker, Eater, Singer…” ↩

-

Carol Leong, “Dead Line,” Straits Times, 12 October 1990, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ponnampalam, “Joker, Eater, Singer…” ↩

-

“Forensic Science Gears Up for Future,” Straits Times, 21 January 1990, 20; “Inside the World-class Forensic Institute,” Straits Times, 24 August 1995, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Pauline Leong, “Mister Autopsy Lives on in ‘Chaozy Bears’,” Straits Times, 10 April 2000, 48. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Karen Wong, “Top Forensic Pathologist Chao Dies in New York,” Straits Times, 23 February 2000, 3; Ponnampalam, “Joker, Eater, Singer…” ↩

-

Wong Chiang Yin, “In Memoriam: Prof Chao Tzee Cheng (1934–2000),” SMA News 32, no. 2 (2000), https://www.sma.org.sg/sma_news/3202/eulogy.pdf. ↩