Red Terror: The Forgotten Story of CPM Violence and Subversion in Newly Independent Singapore

The 1970s are often remembered as a time of rapid economic transformation and progress for Singapore, but this period also saw communist bombings, assassination plots and covert information wars.

By Choo Ruizhi

Strange, red flags fluttered in the midday breeze. At a playground near 10½ Mile Changi Road, that was the only sign that something was amiss that Thursday afternoon on 23 April 1970. Intrigued by the unfamiliar sight, a 9-year-old boy and a 7-year-old girl wandered over to investigate. In doing so, the children unwittingly triggered a booby-trap bomb planted near the red flags, setting off an explosion that was heard by residents almost a kilometre away. The children were rushed to the nearby Changi Hospital. Hours later, the little girl died.1

That same evening, two homemade bombs, packed into red cylinders, were discovered on Haji Lane. Five days later, another explosive was discovered on an overhead bridge near Chinese High School.2 The Bomb Disposal Unit later detonated the explosive at a vacant site near National Junior College. More red flags – bearing the hammer-and-sickle emblems – were recovered by the police along with the bombs. These were the banners and symbols of the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM, also known as the Malayan Communist Party).

In Singapore’s history, communists often feature as dangerous antagonists of the 1950s and 1960s. However, what many have forgotten is that acts of violence continued into the 1970s. In fact, April 1970 marked the start of renewed communist violence on the island.3 Newspaper articles, photographs, and government press releases from the 1970s tell of foiled assassinations, terrorist attacks and clandestine information wars.

A Broader Picture: Communists in Context

This resurgence of communist activity was not spontaneous. The April 1970 bombing in Changi was linked to the CPM’s revival of its armed struggle in Malaysia in June 1968. This revival can be traced to broader regional and international situations at the time, such as the ongoing Vietnam War and Chinese support for the CPM.

The Malayan Emergency, a struggle between the CPM and Malayan, British and British Commonwealth forces, officially ended in July 1960. By then, the CPM had been using non-violent, “united front” tactics for some six years (from 1954 onwards).4 Its main combat units had withdrawn to the Thai-Malayan border, where most were subsequently demobilised.5 In Singapore, the Special Branch had successfully uprooted the CPM’s “underground network throughout the island” by the early 1960s.6 Although party cadres had fled to the Riau Islands prior to these security operations, the CPM’s diminished presence did not mean that it had been eradicated.7

Key leaders like Chin Peng, CPM’s secretary-general, fled to Beijing where they were given support and sanctuary by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Chinese leaders urged CPM leaders to renew their armed struggle as the CCP predicted that a wave of violent revolutions would soon sweep across Southeast Asia.8 Lending further credence to this view was the ongoing Vietnam War between communist and anti-communist (largely American) forces, which only ended in 1975. When Cambodia, South Vietnam and Laos fell to the communists in 1975, Chin Peng asserted that “the tide was turning inexorably in the communist world’s favour, particularly as far as South East Asia was concerned”.9

With moral and material support from the CCP, the CPM revived its uprising in Malaysia. In June 1968, the CPM issued an official directive for cadres to “hold high the great red banner of armed struggle and valiantly march forward!” The document ordered CPM members to overthrow the Malaysia and Singapore governments “by taking up the gun and carrying out the people’s war”. Eight years after the end of the first Malayan Emergency, CPM forces launched an ambush near the town of Kroh in the northern state of Perak killing 17 Malaysian security personnel and injuring 18. Communist operatives began to infiltrate the states of Peninsular Malaysia from south Thailand (where they had fled to after the Malayan Emergency).10

Regarding Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore as one political entity, the CPM sought to establish Singapore as a base to support their insurgency in Malaysia, procuring equipment, funds and support from the city-state.11 With these plans in mind, the renewed communist insurrection soon crossed into Singapore.

More Bombings and Banners

In addition to the fatal bombing in April 1970, 22 cases of arson and 11 bomb incidents were traced to the CPM between 1969 and 1983. In 1971, as a vivid reminder of its power and reach in Singapore, CPM operatives again planted communist banners, flags and dummy bombs across the island.12

In 1974, after a major split within the CPM itself, rival factions intensified their attacks in Singapore to prove their revolutionary zeal. In June, a homemade bomb attached to three communist flags exploded on an overhead bridge outside People’s Park Complex. Throughout the year, Singaporeans were subjected to a succession of dummy bombs, banners, pamphlets and flags inscribed with communist symbols and slogans.13

Perhaps the most sensational incident of this period was the Still Road bombing, also known as the Katong bombing. Around mid-December 1974, Nanyang Shoe Factory managing director Soh Keng Chin received a letter wrapped around a live bullet. Written in Chinese, the threatening note condemned Soh’s exploitation of workers at his Johor Baru factory, which had been shut down in July 1973, and warned him to “be careful”.14

In the early hours of 20 December 1974, three CPM operatives set out to kill Soh. They drove a blue Austin car carrying four bombs, intending to detonate them at Soh’s bungalow in Katong.15 However, while waiting at a traffic junction near Still Road at 5.20 am, one of the volatile explosives in the car suddenly exploded.

The explosion sent glass and metal shards over a 100-metre radius. Witnesses saw “tongues of flames flickering from the mess that was the Austin”, while the morning air was “pungent with the smell of gunpowder”.16

The vehicle’s driver, Gay Beng Guan, 37, was hurled out of the car by the force of the blast. He was found “writhing and groaning in agony from the burns and injuries all over. Blood oozed from… the opening where his left arm had been torn off”. He died about two weeks later in Outram Hospital. Lim Chin Huat, 23, the front-seat passenger, was “smeared with blood, his abdomen ripped open and his arms severed by the blast”. He died at the scene. The third man, Tan Teck Meng, who had been seated at the rear of the car, escaped with severe burns, but he was later caught and detained by police.17

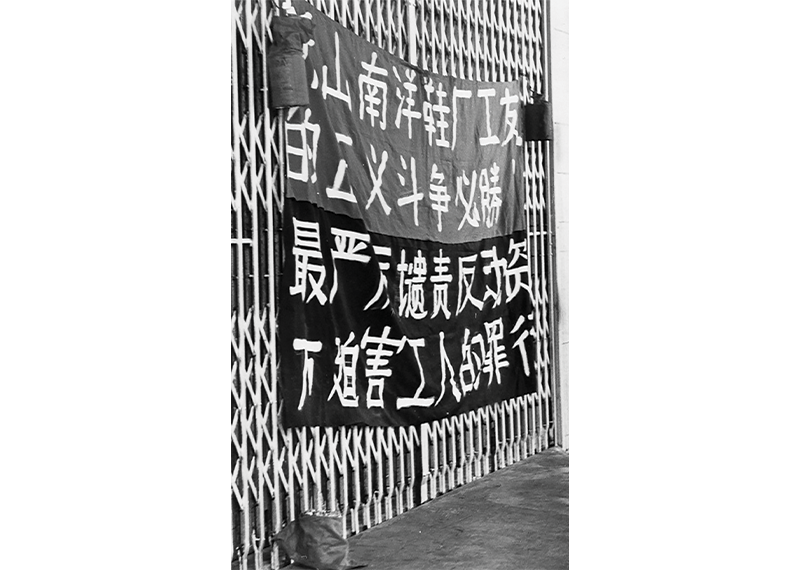

That same morning, police found three more bombs strung across the North Bridge Road office of Nanyang Manufacturing (an affliate company of Nanyang Shoe Factory). The bombs were hung alongside banners that read “The Righteous Struggle of Johor Baru Nanyang Shoe Factory Workers Must Win” and for all to “Most rigorously condemn the persecution of workers by the reactionary management”.18

The horrific deaths of the communist agents – described, photographed and published in vivid detail in newspapers – were perhaps the most sobering demonstration of the bloodshed the CPM was prepared to inflict. Yet these explosions were only the most visible manifestations of the CPM’s operations in Singapore.

Throughout the 1970s, the police and the Internal Security Department (ISD, which succeeded the Singapore Special Branch) uncovered numerous CPM plots to infiltrate local organisations, attack key installations and assassinate government leaders. Although such schemes were fortunately prevented, they illustrate the sheer scale of carnage communist forces were planning to wreak.

Arms, Ammunition and Assassination Plots

Security operations in 1974 uncovered communist banners, flags and simulated booby-traps, along with large troves of arms, ammunition and explosives, which included “42 bullets, one hand grenade, six grenade casings, 16 detonators, one compass, eight gelignite sticks, [and] three crude bombs”.19 Plans to establish a local assassination squad were also discovered, along with electrical diagrams of the homes of key government officials and buildings, drawn up by a CPM member who was an electrical subcontractor.20

These chilling assassination plots mirrored the CPM’s ongoing surgical strikes on key police leaders in Malaysia. On 4 June 1974, Malaysia’s Inspector-General of Police, Tan Sri Abdul Rahman Hashim, was killed by a CPM assassination squad. About 16 months later, in November 1975, Tan Sri Koo Chong Kong, the Chief Police Officer of Perak, was shot and killed in broad daylight in Ipoh, Perak. These same assassins later plotted to kill Singapore Police Commissioner Tan Teck Kim in 1976, but were arrested before they could execute their plan.21 Although Singapore’s security forces were able to narrowly foil such plots, the danger of CPM-fomented terror persisted.

In July 1975, a captured CPM agent led Singapore police officers to a cache of “189 hand grenades, 210 detonators, a .38 revolver, a .25 Colt automatic pistol, 75 rounds of ammunition and several communist books and documents.”22 Later that month, another 109 hand grenades were found in two earthen jars, buried in the grounds of another operative’s house.23 In numerous press releases, the Ministry of Home Affairs detailed the extensive involvement of captured agents with CPM cell leaders, which went as far back as the 1950s.24

Another ISD sweep captured four more communist cells in 1977, which comprised local construction workers and even a reservist SAF officer. One of these CPM units was a construction company involved in the building of drains in Tuas Village and Newton Road. These projects had raised $46,000 for the CPM.25 That same year, a full-time national service police inspector was arrested for providing “confidential information”, such as the car registration plate numbers and names of key ISD personnel.26

Taken together, such discoveries indicate that the CPM had planned catastrophic terrorist attacks on the island, so as to “oppose the reactionary rule” of Singapore’s government and to “unyieldingly take the road of armed struggle”.27

Yet CPM members alone could not “liberate… Malaya including Singapore”.28 To succeed, its agents needed to recruit people to their revolutionary cause. As communist banners and bombs mushroomed across the island, a parallel struggle for the hearts and minds of regular Singaporeans was also underway, one which played out in underground networks and across Singapore’s airwaves.

Information War: Underground and Over the Airwaves

CPM operatives quietly sought out sympathisers through informal channels, cultivating disillusioned, well-meaning residents who wanted to build a more equal and just society. Under the guise of conducting Chinese tuition or discussing Chinese culture, CPM operatives slowly indoctrinated potential recruits with communist literature. These underground networks led by CPM elements enabled the party to not only gradually amass classified intelligence, funds and equipment for their cause, but to also develop local satellite organisations, often led by indoctrinated “revolutionary youths”.29

Concurrently, the CPM waged an information offensive over Singapore’s airwaves. In November 1969, using powerful broadcasting equipment supplied by the CCP, the Voice of Malayan Revolution (VMR) began radio broadcasts from a mountainous region in South China, seeking to disseminate the “the revolutionary truth and news of our army’s victories and of the people’s struggle” to all listeners within range.30

Listeners in Singapore could tune in to VMR broadcasts twice daily on AM radio. On 29 July 1970, Singapore Telecoms began jamming these long-range transmissions, but with limited success.31 VMR broadcasts continued until June 1981 when the station was shut down on the CCP’s orders. Despite the VMR’s closure, the CPM continued radio broadcasts from a new radio station called Suara Demokrasi (Voice of Democracy) from a new mobile transmitter on the Thai-Malaysian border until the signing of the 1989 Haadyai Peace Agreement.32

CPM Leader Chin Peng claimed that many communist sympathisers and cadres throughout Malaysia and Singapore “tuned in eagerly” to the radio broadcasts.33 However, Eu Chooi Yip, a senior CPM cadre and who was also director of VMR’s Chinese programming section, disagreed. In an oral history interview in 1992, Eu described many of VMR’s programmes as simply a rehash of existing news reports from local newspapers with the addition of communist rhetoric. Eu recounted how cadres on the ground were in fact “not really willing to listen” to the programme, likening the broadcasts to serving “leftover rice” (“他们说连他们自己也不大愿意听, 打开电台听一下… 就不听了… 和炒冷饭一样”).34

Adding to the challenge was that VMR had to compete for attention from the likes of the highly popular Rediffusion radio service. By 1975, Rediffusion boasted a Chinese adult listenership of about 229,000.35 VMR’s austere, often repetitive, revolutionary pronouncements offered no substantive rejoinder to Rediffusion’s dazzling programming.36

The growing access to television in Singapore further blunted VMR’s allure. A 1979 government survey revealed that nine out of 10 households owned a television and about one-fifth owned colour television sets, a statistic that also reflected the growing prosperity of Singaporeans. VMR’s propaganda had to compete with programmes such as the first live, colour telecast of the World Cup football final in 1974 between the Netherlands and West Germany.37

The CPM’s information offensive did succeed in enticing some Singaporeans, even people in authority. In 1979, two prison wardens at the Moon Crescent Detention Centre confessed to smuggling cassette recorders into the compound for inmates to tape VMR broadcasts and to passing VMR transcripts between detainees.38

Another View of the 1970s

Today, whether in local textbooks, museum exhibitions or personal accounts, the 1970s are primarily remembered as a period of economic growth in Singapore’s history. On the surface, it appears as an uncomplicated, transitional decade: between the chaos of the 1960s and self-confidence of the 1980s.

However, newspaper articles, government reports, oral histories and scholarly studies reveal that the 1970s were far more volatile and uncertain than more conventional historical accounts let on. The April 1970 Changi bombing heralded the start of renewed communist violence and subversion in Singapore. Although the police and ISD successfully foiled most of these plans, the regular discoveries of these assassination plots, arms caches and cell groups point to a sustained, systematic CPM presence in Singapore, even after the chaotic upheavals of the 1960s.39

The vigilance of local security forces resulted in a significant drop in bombings and arson attacks in the 1980s. The government, however, remained alert to subversive efforts by CPM agents, aware that the “communists work with a long term view, gradually infiltrating political parties, unions, the armed forces and other major bodies”.40

The communist threat, though diminished, persisted until 2 December 1989 when the CPM signed the Haadyai Peace Agreements at the Lee Gardens Hotel in the southern Thai city of Haadyai. Over 1,100 CPM guerrillas agreed to lay down their arms in an “honourable settlement” that brought the 41-year conflict to a formal close.41

Choo Ruizhi is a Senior Analyst with the National Security Studies Programme at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University. His other research interests include the environmental histories of Southeast Asia in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Choo Ruizhi is a Senior Analyst with the National Security Studies Programme at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University. His other research interests include the environmental histories of Southeast Asia in the 19th and 20th centuries.NOTES

-

“Bomb Victim Dies,” Straits Times, 25 April 1970, 1; “Flag Bombs Go Off in S’pore Too,” Straits Times, 24 April 1970, 1; John Tan, “Underground Network’s Deadly Record,” Straits Times, 30 November 1983, 22. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Bomb Found on Bridge,” Straits Times, 30 April 1970, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chua Sian Chin, “Communism – A Real Threat”, in Socialism That Works… the Singapore Way, ed. C.V. Devan Nair (Singapore: Federal Publications, 1976), 12. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 335.0095957 SOC) ↩

-

Lee Ting Hui, The Open United Front: The Communist Struggle in Singapore, 1954–1966 (Singapore: South Seas Society, 1996), 6. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5703 LEE) ↩

-

Ong Weichong, “Securing the Population from Insurgency and Subversion in the Second Emergency (1968–1981)” (PhD thesis, University of Exeter, 2010), 59. ↩

-

Chin Peng, Ian Ward and Norma O. Miraflor, My Side of History (Singapore: Media Masters, 2003), 439. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5104092 CHI) ↩

-

Fong Chong Pik, Fong Chong Pik: The Memoirs of a Malayan Communist Revolutionary (Petaling Jaya: Strategic Information and Research Development Centre, 2008), 172. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5704092 FAN-[HIS]) ↩

-

Chin, Ward and Miraflor, My Side of History, 428–30. ↩

-

Chin, Ward and Miraflor, My Side of History, 453. ↩

-

Aloysius Chin, The Communist Party of Malaya: The Inside Story (Kuala Lumpur: Vinpress, 1995), 164. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.51 CHI); Chua, “Communism,” 12–13; Bilveer Singh, Quest for Political Power (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd, 2015), 165. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 335.4095957 SIN) ↩

-

“For Ops across Causeway… Reds Want Singapore as Base, IGP Warns,” Straits Times, 13 October 1978, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tan, “Underground Network’s Deadly Record”; “Bomb Hoax, Pro-Red Banners Keep Police Busy,” Straits Times, 3 January 1971, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Leslie Fong and Paul Wee, “Booby-trap Escape,” Straits Times, 21 June 1974, 1; “Red Banners Seized at Bridges,” Straits Times, 5 November 1974, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Bharathi Menon, “Bullet Warning from Bombers,” New Nation, 24 December 1974, 1; “The Katong Bomb Incident,” Today, 20 October 2011, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“24-hour Police Vigil for Articles with Red Slogans,” Straits Times, 28 December 1974, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Paul Wee, “Riddle of Bomber No 3,” Straits Times, 22 December 1974, 1; Paul Wee, “Hunt for Bomber No 3,” Straits Times, 21 December 1974, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Wee, “Hunt for Bomber No 3”; “Katong Blast Bomber Dies,” Straits Times, 4 January 1975, 8; Lai Yew Kong, “Bombers’ Link with Reds,” Straits Times, 23 December 1974, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Vital Clues in the Bombers’ Warning Notes…,” New Nation, 27 December 1974, 2; “Implications of the Bomb Blast,” New Nation, 23 December 1974, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

P.M. Raman, “30 Detained in Security Raids,” Straits Times, 22 June 1974, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tan, “Underground Network’s Deadly Record”; “Communist Threat,” Straits Times, 6 October 1975, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chin, Communist Party of Malaya, 164, 236–38. ↩

-

Ahmad Osman, “Police Seize 298 Hand Grenades,” Straits Times, 5 August 1975, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

See, for instance, Osman, “Police Seize 298 Hand Grenades”; “Freed: Woman Who Was Plen’s Courier,” Straits Times, 23 June 1972, 6; “Ex-detainee: I Was Trained to Use Guns and Grenades,” Straits Times, 21 May 1980, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“39 Arrested in ISD Swoops,” Straits Times, 16 October 1977, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Singh, Quest for Political Power, 168; “Former Officer: I Leaked Secrets to Reds,” Straits Times, 13 October 1978, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Voice of Malayan Revolution Broadcast, 1 May 1980” in Voice of Malayan Revolution: The CPM Radio War Against Singapore and Malaysia, 1969–1981, ed. Wang Gungwu and Ong Weichong (Singapore: RSIS, 2009), 218. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 322.4209595 VOI) ↩

-

Raman, “30 Detained in Security Raids.” ↩

-

“Former Officer”; “Detainee Admits: I Was a Leader of Revolutionary Group,” Straits Times, 20 November 1977, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Fifty Years of the CPM (Part VI), 28 June 1981” in Voice of Malayan Revolution: The CPM Radio War Against Singapore and Malaysia, 1969–1981, ed. Wang Gungwu and Ong Weichong (Singapore: RSIS, 2009), 87. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 322.4209595 VOI) ↩

-

Original source figures given as 9590 kc/s and 7305 kc/s in the 31- and 41-metre bands. “Internal Security Department (Singapore) Files: The Voice of the Malayan Revolution, 26 May 1971” cited in Ong Weichong, Malaysia’s Defeat of Armed Communism (New York: Routledge, 2015), 51. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 322.4209595 VOI) ↩

-

Chin, Ward and Miraflor, My Side of History, 460. ↩

-

Chin, Ward and Miraflor, My Side of History, 450. ↩

-

Eu Chooi Yip (余柱业), oral history interview by 林孝胜, 25 September 1992, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel 19 of 23, 30:32, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 001359). ↩

-

Eddie C.Y. Kuo, “Multilingualism and Mass Media Communications in Singapore”, Asian Survey 18, no. 10 (October 1978): 1067–83. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

For more examples of the VMR’s broadcasts, see Voice of Malayan Revolution: The CPM Radio War Against Singapore and Malaysia, 1969–1981, ed. Wang Gungwu and Ong Weichong (Singapore: RSIS, 2009). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 322.4209595 VOI) ↩

-

“S’poreans and Their Rising Affluence,” Straits Times, 30 October 1979, 1; “Soccer ‘Live’ Colour Telecast was ‘Superb’,” Straits Times, 9 July 1974, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Sit Meng Chue, “Two Who Were Won Over by Pro-Red Detainees,” Straits Times, 2 June 1979, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Leon Comber, Malaya’s Secret Police, 1945–60: The Role of the Special Branch in the Malayan Emergency (Singapore, ISEAS Publishing, 2008), 6. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 363.283095951 COM) ↩

-

“The Red Threat Is Very Real,” Singapore Monitor, 28 January 1984, 17. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tan Lian Choo, “Accord is An Honourable Settlement, Says Chin Peng,” Straits Times, 3 December 1989, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩