This Was Once Singapore’s Largest Planned Housing Development: A History of Sennett Estate

Sennett Estate is a unique milestone in the history of housing development in Singapore and its quiet streets have had its fair share of excitement over the years.

By Winnie Tan

At first glance, there is little to suggest that Sennett Estate, a housing development in Potong Pasir just off MacPherson Road, is particularly noteworthy. It looks like any typical suburb, with its quiet streets lined with houses that were originally built in the 1950s. However, this unassuming estate represents an interesting milestone in the history of home development in Singapore.

Developed in response to the post-war housing crunch, Sennett Estate was once dubbed the biggest planned housing estate in Singapore.1 And within the 170 acres that make up this quiet estate are stories that link the place to Singapore’s larger history: to a time when wealthy Arab families owned large tracts of land and also to a period in crime-infested Singapore when kidnapping was a common occurrence. It is even, somewhat improbably, tied to the Konfrontasi.

Alkaff Lake Gardens

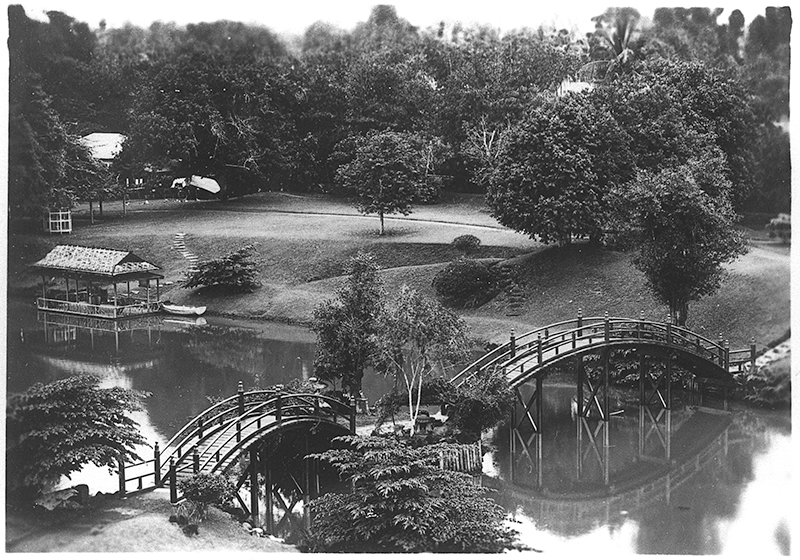

Before Sennett Estate came into being, the area was principally known for the Alkaff Lake Gardens. In the late 1920s, the park was developed by Syed Shaik Abdul Rahman Alkaff of the Alkaff family, a prominent Arab family of merchants and property developers.2

“Eighteen years ago, the idea of converting the site into a park occurred to me,” he said in a 1948 newspaper interview. “A building contractor suggested that we should decorate the site with Japanese tea-houses, side-walks lined with granite chips, Japanese arches and bridges,” he said. Alkaff then hired a Japanese landscape expert to develop what has been described as Singapore’s very first Japanese-style garden across 10 acres (40.5 sq m) of land, which opened to the public in 1929.3

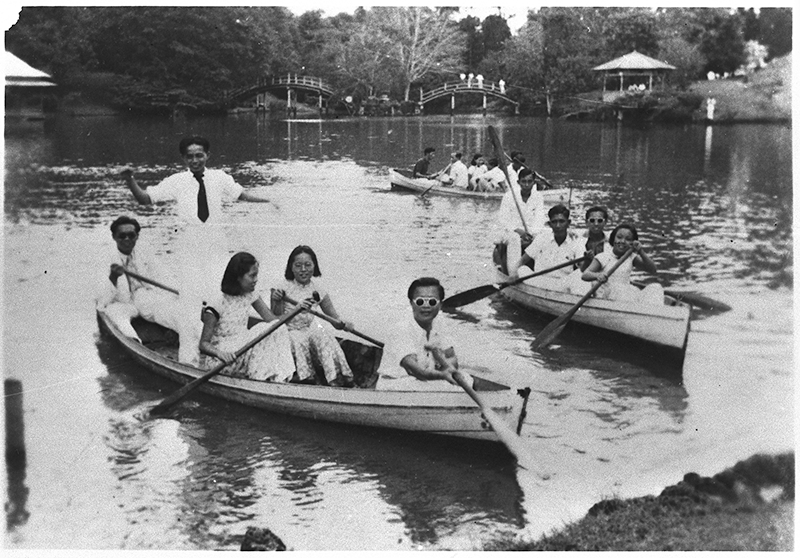

Alkaff Lake Gardens quickly became a popular evening and weekend resort for families, couples and office workers.4 Featuring artificial hills and a man-made lake, visitors could go boating on the lake, fishing and picnic under shady trees.5 The idyllic spot also offered tea houses that could be rented, interspersed among quaint Japanese bridges and manicured shrubbery.

In 1935, Chinese merchant Tan Aik Kee of Nanyang Amusement Co. took over the management of the park and introduced Chinese elements. Chinese-style boathouses reminiscent of dwellings along the Pearl River in Guangzhou were constructed along with Chinese pavilions as well as the introduction of Chinese white and pink lotus flowers.6 A cinema and a cabaret were even in the works. However, the park fell into disuse by the late 1930s.

The War

At the onset of World War II, the park was requisitioned by the British military in December 1941 and closed to the public. The Singapore Volunteer Field Ambulance Corps then took over the area and made it their headquarters, where they were stationed for a few weeks. The park was initially spared from Japanese bombings and a former sergeant from the volunteer corps believed that this was because there was a “huge red cross set up on the grass, which was visible even from the air”. However, after the volunteer corps moved out, the park was bombed and shelled.7

The park continued to be off limits during the Japanese Occupation. An armed guard was stationed at the park during those years and even the owner, Syed Shaik Abdul Rahman Alkaff, was prohibited from entering. After the war, the park lay derelict and was overgrown with grass and weeds. As the Alkaffs decided to return to their core business of trading, much of their property, including the park, was sold after the war.8

At the end of the tumultuous decade, Alkaff Lake Gardens and the adjacent plots of land were purchased by Sennett Realty in July 1950 with plans to develop a new housing estate there.9 It was the end of an era and the beginning of a new one.

Planning the Biggest Housing Estate

After the war, Singapore’s population increased exponentially, causing a severe housing shortage. In 1947, a study by the Singapore Housing Committee revealed that the colony’s population had increased from 560,000 in 1931 to 941,000 that year, with most families crammed into one room or even just a cubicle. The committee found that barely one-third of the urban population was housed satisfactorily.10

In July 1950, the Sunday Times reported the plans for the new Sennett Estate, the first private enterprise development in Singapore to be built after World War II as a response to the housing shortage. Dubbed the “biggest housing estate planned”, it would have 1,400 homes built on 170 acres of land – bordered by Upper Serangoon Road, MacPherson Road and Upper Aljunied Road – with houses priced at an average of $10,000 each, including land and installation.11

The estate would comprise shophouses, bungalows, semi-detached houses and terrace houses, according to C.W.A. Sennett, the managing director of Sennett Realty. “When the plots of land were earmarked, prospective buyers could either buy the land itself and build their own house, according to their own specifications, or have a house built for them by the Sennett Realty Co,” he said.12 Sennett himself was closely associated with land development in Singapore, having been the former Commissioner for Lands and then Chairman of the Singapore Housing Committee

Sennett told the Sunday Times that the company would “endeavour to bring down the price of private houses to meet the pocket of the middle-class man”. “The financial arrangements for people buying housing on the hire-purchase system would have to be worked out with the building society, but the usual terms for borrowing $10,000 was to pay it back at the rate of $85 a month over 15 years,” he said. All the houses in the estate would be equipped with modern sanitation, water, electricity and gas. The initial proposal for the estate also included a clinic, market, cinema and kindergarten.13

Around the same time, it was announced that Alkaff Lake Gardens would be “filled up with earth and the hillocks levelled to be converted into children’s playgrounds and open spaces”.14 Although the park was deemed “a ghost of its pre-war self” by the Straits Times at this point, its closure was still met with howls of protest from the public, who lamented the dearth of open spaces in Singapore.

In July 1950, a Straits Times reader wrote to the paper to express his “indignant distress and alarm” at the impending fate of Alkaff Gardens. “If this is thought a noble service to the community, towards relieving the present housing shortage, then the impression is certainly highly mistaken.”15 Another reader wrote to the Straits Budget, asking rhetorically: “Is Singapore so well stocked with public parks and open spaces that we can afford to see this God-given man-made beauty spot of our city obliterated?”16 The Singapore Progressive Party issued a statement saying that Alkaff Gardens should be “preserved as a public park” and called upon the “‘relevant public authority’ to take necessary steps for this purpose”.17

While Sennett agreed that “Singapore was badly off for open spaces”, he said that “these things must be planned for the whole of the Colony instead of picking on one isolated spot such as the former Alkaff Gardens”. Moreover, the lake was “really a hole in the ground filled with rain water and breeding mosquitoes”.18 Sennett did promise that trees from the Alkaff Lake Gardens would be kept and replanted in Sennett Estate’s new parks.

Within a month of the estate’s debut announcement in August 1950, more than 1,000 people had applied to buy the 1,400 units available. In February 1951, Sennett Realty announced that the foundations for the first batch of residential and shop houses were being laid, and the units would be allocated on a “first come, first served” basis.19

Meanwhile, representatives from the Sennett housing estate and the Public Works Committee discussed potential names for the estate’s 24 roads. The names of the directors of Sennett Realty were initially suggested for the roads to honour the businessmen’s “courage and enterprise” in this first-of-its-kind development. However, the committee rejected these names, on the grounds that these private roads would eventually be taken over and maintained as public roads by the Municipality so the names should be approved by the municipal commissioners.20

After much debate, a compromise was reached. The roads within the estate were named after flora and fauna, such as Butterfly Avenue, Cedar Avenue and Lichi Avenue, as well as after the businessmen involved in the project. These include Pheng Geck Avenue, after City Councillor Yap Pheng Geck; Kwong Avenue, after A.C.T. Kwong, director and manager of Sennett Realty; and Wan Tho Avenue, after Loke Wan Tho, film magnate and founder of Cathay Organisation. The first section of the estate was built in 1951, with the remaining three phases completed over the following years.21

The Early Days

One long-time resident of the area is 68-year-old Julie Kwong, daughter of the late A.C.T. Kwong, who was also once the Chinese general consul in Ipoh. To this day, the retired lawyer and current school administrator lives on the same road that bears her last name.

According to Julie, her father had been the director and manager of Sennett Realty Co. as well as the managing director of the Malayan Realty Co. “In 1956, land was transferred from Sennett Realty to my mother, who together with my father developed plots of land under Kay & Arthur Pte. Ltd.”22 All three companies played a major role in developing the estate.

Having lived in the estate for more than 60 years, Julie recalls how flooding used to be a major problem. As a child in the 1950s, she remembers that when it flooded, she and her siblings “sat atop furniture, made paper boats and floated them” in their living room. “It was fun.”23

The adults, undoubtedly, found the situation less amusing. “The floods here are getting worse every time it rains,” said resident R. Manikam to the Singapore Free Press in 1954. “It looks like we are being left to either sink or swim in them.” Another resident, F.S. Krempl, added: “We have to remove shoes and roll up trousers to get to the main road. Sometimes we think how nice it would be to have a motor boat service here.”24

In 1954 alone, residents counted 32 floods, during which water would seep through the walls and floors, rendering the bathrooms and flush systems unusable. “Nuisance from flooding, flies and mosquitoes is getting intolerable,” they said.25 The residents repeatedly petitioned the City Council to fix the problem.

Potong Pasir, where Sennett Estate lies, has long been prone to flooding. It is a low-lying area, and when it rained, the nearby Kallang River would overflow its banks, flooding the vicinity. To prepare for the monsoon season, pig farmers in Potong Pasir at the time would dredge the river to mitigate the floods.26

In 1953, the City Engineer’s Department enlarged the culverts of drains on Upper Serangoon Road. Although the department noted that “these modifications [had] removed all back flooding into the estate”, residents still complained of flooding whenever it rained.27

More drainage works ensued in the next decade, but the situation only improved from 1964 when the government approved a $52,000-flood alleviation scheme to extend existing drains that were too narrow and shallow in the area.28

After this scheme, there were no more news reports about flooding in Sennett Estate. While flash floods still occasionally plague the area, they are no longer as severe thanks to the flood control measures in place.

Schools and Places of Worship

By the 1960s, there were five government schools in the area – Willow Avenue Secondary School, Cedar Girls’ Secondary School, Cedar Primary School, Kwong Avenue School and Sennett Estate Primary. When Alkaff Lake Gardens was finally levelled in 1964, the first three schools were built on the very land where the park once stood.29

“During school dismissal time, the school children would always be at our fence and at our front gate, catching spiders along our hedge, or just hanging out by the gate,” recalled Julie. As the family’s entertainment-cum-family room was situated near the gate, she and her siblings would make music in the afternoons, much to the delight of the children. “My sister would be playing the piano here, my brother on the drums, another sister would be on the accordion,” she recalled.30

Willow Avenue Secondary School closed in 1991 due to falling enrolment.31 At the same time, neighbouring Cedar Girls’ Secondary School was torn down, with the new school premises ultimately located on the site of the former Willow Avenue Secondary School.32 Although the new building is now situated along Willow Avenue, Cedar Girls’ Secondary School was allowed to retain its original address of 1 Cedar Avenue.33

Kwong Avenue School subsequently merged with Sennett Estate Primary to form Sennett Primary School, occupying the former’s premises on Kwong Avenue. Sennett Primary closed in 1999 and its pupils were transferred to Cedar Primary School.34 A hostel was later built at that location for tertiary students, but the premises have since been taken over by the Boys’ Brigade headquarters.35

Apart from schools, Sennett Estate also has several places of worship. Alkaff Upper Serangoon Mosque is located at 66 Pheng Geck Avenue while Calvary Baptist Church is at 48 Wan Tho Avenue. In addition, Sri Siva Durga Temple is located nearby at 8 Potong Pasir Avenue 2.

Sennett Estate’s most notable neighbour though was Bidadari Cemetery. The cemetery opened in 1908 and served the Christian, Muslim, Hindu and Sinhalese communities until its closure in 1972. The proximity to a major cemetery did not seem to have deterred homebuyers. “People were more afraid of bumping into cobras,” Julie said. Since Mount Vernon Camp, which houses the training and residential facilities of the Gurkha Contingent in Singapore, is located near the cemetery, she added that the estate’s residents always felt safe near the burial grounds.36

Dangerous Liaisons

While Sennett Estate and Singapore are relatively crime-free today, this was not the case in the 1960s. Crimes involving firearms were common and kidnapping was a regular occurrence. No place was safe, not even quiet neighbourhoods like Sennett Estate.

In November 1964, rubber magnate Ng Quee Lam was visiting a friend living on Kee Choe Avenue one night when a group of four men pulled him out of his car. “Two of them came for me – one from each side of the car. A third man had already stuck a revolver against my driver’s chest,” Ng told the Straits Times. As this happened in the early evening, Ng had hoped that there would be people around to come to his rescue, but unfortunately no help came.37

Ng was only freed two weeks later, and the bungalow where he was held captive was on Sommerville Road, off Upper Serangoon Road, just a mere seven minutes’ drive from the estate.38 To deter abductions and secret society activities, the Singapore government enacted the Kidnapping Act and revised kidnapping charges in 1961, raising the maximum penalty from 10 years to death or life imprisonment.39

The 1960s was also the period of the Confrontation or Konfrontasi. Indonesia’s opposition to the formation of the Federation of Malaysia resulted in armed incursions, bomb attacks and other subversive acts in Singapore and Malaysia between 1963 and 1966.40 The bombing of MacDonald House on 10 March 1965 is possibly the best-known incident associated with Konfrontasi. The explosion tore through the building, killing three people and injuring at least 33 others.41

However, prior to the MacDonald House attack, 29 bombs had already been indiscriminately set off throughout the island. On 9 December 1963, one of those bombs was planted under a car in the back lane of Jalan Wangi in Sennett Estate. The blast killed two Indian shopkeepers operating a five-footway cigarette and sundries stall.42

“Many of the residents were shocked to hear of the incident,” recalled Julie.43 However, as her home was situated on the other side of the estate, she only learned about the explosion through news reports.

A New Alkaff Lake

While the old Alkaff Lake Gardens is no more, the Housing and Development Board announced in 2013 plans to construct a new Alkaff Lake in Bidadari Park, just 500 metres north of the original lake.44 Apart from beautifying the area, the new lake will also act as a retainer for stormwater before it is discharged into Marina Reservoir.45

The new Alkaff Lake – envisioned to be around the size of two football fields and hold 30 million litres of water – will also be the country’s first artificial lake to double as a flood control feature.46 (At the time of publishing, there has still been no word on when the lake and park will be ready.)

Today, Sennett Estate is dwarfed by tall condominium developments and the highly popular Bidadari housing estate. However, within Sennett Estate itself, little appears to have changed. Looking back, Julie agrees that on the surface, the estate is still very similar to what it used to look like a half century ago. However, the rhythm of life in the area is no longer the same, she said, lamenting the loss of street hawkers and the Friday night pasar malam.47

“The chwee kueh lady would wheel [her cart] down the streets, her steamer in front, and the laksa man would walk by with ceramic bowls and a huge pot,” she said. “They would be on our street and we’d buy from them. They have calls that still ring in my ears today.”48

Winnie Tan is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She is part of the Arts and General Reference team and works on content development, collection management, and research and reference services.

Winnie Tan is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She is part of the Arts and General Reference team and works on content development, collection management, and research and reference services.NOTES

-

“Biggest Housing Estate Planned,” Straits Times, 16 July 1950, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Dhoraisingam S. Samuel, Singapore’s Heritage: Through Places of Historical Interest (Singapore: Dhoraisingam S. Samuel, 2010), 19. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 SAM-[HIS]) ↩

-

Roy Ferroa, “S’pore’s Forgotten Park,” Singapore Free Press, 20 April 1948, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Alkaff Gardens Becoming a Popular Park,” Sunday Tribune, 23 February 1936, 17. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ray K. Tyers, Ray Tyers’ Singapore: Then & Now, revised and updated by Siow Jin Hua (Singapore: Landmark Books, 1993), 199. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 TYE-[HIS]) ↩

-

“Alkaff Gardens Becoming a Popular Park”; “Brighter Alkaff Gardens,” Straits Times, 17 September 1935, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ferroa, “S’pore’s Forgotten Park.” ↩

-

Ferroa, “S’pore’s Forgotten Park”; Tyers, Ray Tyers’ Singapore, 199. ↩

-

C.M. Turnbull, A History of Modern Singapore 1819–2005 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2020), 382. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 TUR-[HIS]) ↩

-

“Biggest Housing Estate Planned”; “400 Houses to Go Up in Alkaff Area,” Singapore Free Press, 29 December 1950, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Garden Lake To Be Filled Up,” Straits Times, 18 July 1950, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Speramus Meliora, “A Serangoon Park,” Straits Times, 21 July 1950, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Pieces of Eight, “Alkaff Gardens,” Straits Budget, 27 July 1950, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Wants Alkaff Gardens Preserved,” Singapore Standard, 29 July 1950, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“It’s Really a Hole,” Singapore Free Press, 22 August 1950, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Thousand Apply to Buy Houses,” Singapore Free Press, 22 August 1950, 5; “First Come First Served Allocation System,” Sunday Standard, 18 February 1951, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Name Roads After Malayan Trees, MCs Tell Housing Estate Owners,” Singapore Free Press, 23 June 1951, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“‘Personal’ Names for New Roads,” Straits Times, 27 September 1951, 7; “Sennett’s Aim Is 1000 Houses,” Straits Times, 19 August 1951, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Julie Kwong, interview, 5 May 2022. ↩

-

Julie Kwong, interview, 25 November 2021. ↩

-

“Floods! Call for Action,” Singapore Free Press, 27 July 1954, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Tempers Go Up With the Flood in Estate,” Straits Times, 12 December 1954, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Drainage Works at Potong Pasir,” National Heritage Board, last updated 2 April 2021, https://www.roots.gov.sg/Collection-Landing/listing/1117739. ↩

-

“Flood Drains for Sennett Estate,” Straits Times, 28 August 1964, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Nature Lover, “Vanishing Parkland at Alkaff ‘Gardens’,” Straits Times, 23 May 1964, 17; Au Yee Pun, “When Trees Must Make Way for New Schools,” Straits Times, 6 June 1964, 15. (From Newspaper SG); Gary Maurice Dwor-Frecaut, “Alkaff Lake Gardens,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 2010. ↩

-

Julie Kwong, interview, 25 November 2021. ↩

-

Sandra Davie, “Some Schools in Older Housing Estates to Close,” Straits Times, 17 December 1990, 24. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Cedar Girls to Relive Memories Before Old School Is Torn Down,” Straits Times, 31 October 1989, 17. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Cedar Girls to Lose Its Track and Field,” Straits Times, 6 September 1994, 25. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Annabel Leow, “School Mergers 2019: Merry-go-round of Mergers for Some Affected Primary Schools,” Straits Times, 20 April 2017, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/education/merry-go-round-of-mergers-for-some-affected-primary-schools. ↩

-

“Relocation to Temporary Office from Tuesday, 7 September 2021,” The Boys’ Brigade in Singapore, accessed 25 April 2022, https://www.bb.org.sg/contact-us/address-n-map. ↩

-

Alex Chow, “Bidadari Cemetery,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 15 July 2015; Julie Kwong, interview, 25 November 2021. ↩

-

Lim Beng Tee and Jackie Sam, “Dato Tells How He Was Kidnapped, Held and Freed After 14 Days,” Straits Times, 30 November 1964, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Police Find Kidnap House,” Straits Times, 8 December 1964, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Maria Almenoar, “Sheng Siong Kidnapping: Singapore Was a Hotbed of Abductions in the 1950s and 1960s,” Straits Times, 10 January 2014, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/sheng-siong-kidnapping-singapore-was-a-hotbed-of-abductions-in-the-1950s-and-1960s. ↩

-

Mushahid Ali, “Konfrontasi: Why Singapore was in Forefront of Indonesian Attacks,” RSIS Commentary, no. 062, 23 March 2015, https://www.rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/rsis/co15062-konfrontasi-why-singapore-was-in-forefront-of-indonesian-attacks/. ↩

-

Mohamed Effendy Abdul Hamid and Kartini Saparudin, “MacDonald House Bomb Explosion,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 7 August 2014. ↩

-

“Two on Bombing Charge,” Straits Times, 12 May 1964, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Julie Kwong, interview, 25 November 2021. ↩

-

“New Alkaff Lake for Bidadari Estate,” Today, 29 August 2013, https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/new-alkaff-lake-bidadari-estate. ↩

-

“Bidadari Park,” Housing & Development Board, last updated 18 November 2021, https://www.hdb.gov.sg/cs/infoweb/about-us/hdbs-refreshed-roadmap-designing-for-life/live-well/bidadari-park. ↩

-

Christopher Tan, “Bidadari to Have Flood Prevention Lake,” Straits Times, 14 March 2020, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/environment/bidadari-to-have-flood-prevention-lake. ↩

-

Julie Kwong, interview, 5 May 2022. ↩

-

Julie Kwong, interview, 25 November 2021. ↩