They Died for All Free Men: Stories from Kranji War Cemetery

Remembering those who died while fighting the Japanese during World War II.

By Janice Loo

It was shortly after 4 am on 8 December 1941 when 17 Japanese naval bombers took off from Saigon (now known as Ho Chi Minh City) to attack the airfields at Tengah and Seletar in Singapore.1

That air raid claimed 61 lives and injured 133. Among those who died was Corporal Raymond Lee Kim Teck of the Straits Settlements Volunteer Force. His remains (plot 36, row E, headstone 12) rest among the graves of other Commonwealth casualties from the war on the tranquil grounds of the Kranji War Cemetery.2

Kranji and the Battle for Singapore

Located in the northwestern part of Singapore, the Kranji area became a military base in the 1930s and was a munitions depot before being converted into battalion headquarters for Australian troops after the Allied withdrawal from Singapore on 31 January 1942.3

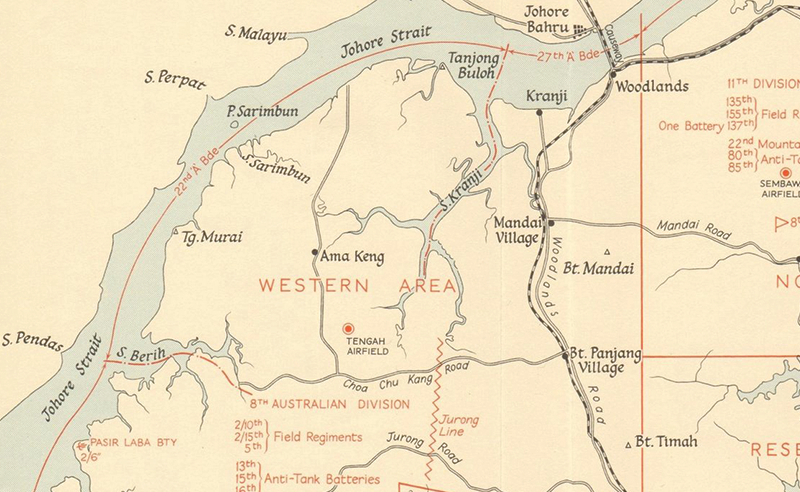

Kranji was a key battle site during the Japanese invasion. With the loss of Malaya, the retreating Allied units were redeployed in a new defence perimeter around Singapore. The 8th Australian Division, comprising the 22nd and 27th Brigades, was stationed to defend the northwestern coastline that became the initial battleground from 8 to 10 February 1942. Overstretched and outnumbered, the Australian troops bore the brunt of the initial Japanese assault. Of the 2,690 burials and inscriptions of missing Australian personnel at the cemetery, 519 have their date of death recorded as between 8 and 10 February 1942, suggesting that they fell in action during the opening battles. The location of the cemetery is thus significant considering that Kranji was where the war began and ended for many.4

Situated on a low hill overlooking the Strait of Johor, the cemetery started out as a small graveyard attached to a prisoner-of-war (POW) camp and makeshift hospital during the Japanese Occupation.5

After the Japanese surrender in September 1945, the site was expanded into a permanent war cemetery managed by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) headquartered in the United Kingdom, an organisation established in 1917 to care for the remains of World War I casualties. War graves were relocated from POW camps and cemeteries from other parts of the island to Kranji, which would serve as the main burial ground for Commonwealth casualties of World War II.6

Unveiled on 2 March 1957, the cemetery honours the men and women from Britain, Australia, Canada, Sri Lanka, India, Malaya, the Netherlands and New Zealand who gave their lives in the line of duty. Designed by the British architect Colin St Clair Oakes, the cemetery contains 4,461 burials marked by headstones as well as five memorials: the Singapore Memorial, the Chinese Memorial, the Singapore (Unmaintainable Graves) Memorial, the Singapore Cremation Memorial and the Singapore Civil Hospital Grave Memorial.7

Within the cemetery, the rows of white headstones are set on a gentle, green slope. As far as possible, each headstone marks the burial of a single person, reflecting the CWGC’s principle of individual commemoration.8 The headstones are of the same shape, size, and material, expressing another principle: the uniformity of sacrifice regardless of rank, race or creed.9

Organised in a square formation of 100 headstones (five rows of 20 headstones), the cemetery is laid out like a military parade, with the war dead forming a battalion that continues to march on.10

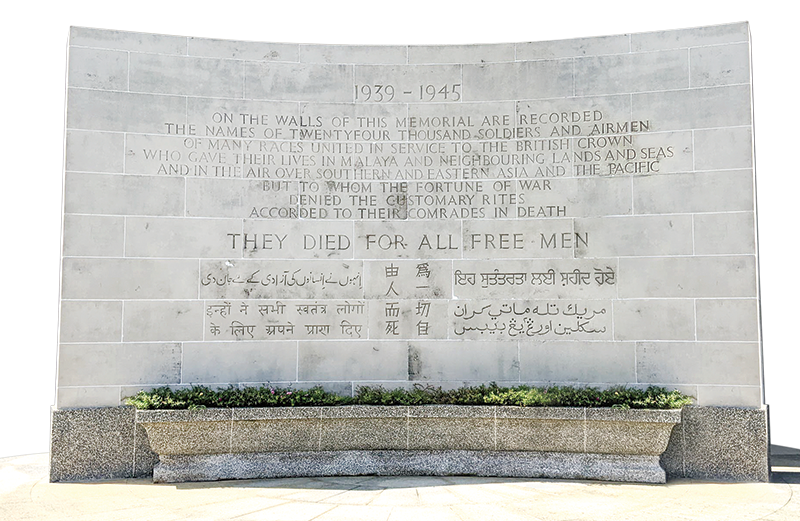

Beyond the graves, on the hill’s highest point, stands the Singapore Memorial – also designed by Oakes. This structure features 12 stone-clad columns bearing the inscribed names of over 24,000 missing personnel with no known graves. The columns are surmounted by a flat, wing-shaped roof. A 22-metre-tall pylon, which resembles the tail unit of an aeroplane, rises from the centre and is capped by a star.11

Four other commemorative panels stand around the Singapore Memorial. Located on the eastern terrace is the Singapore Civil Hospital Grave Memorial, which lists the names of 107 Commonwealth servicemen whose remains lie buried along with those of 300 civilians in a mass grave at the Singapore General Hospital. Situated behind the Singapore Memorial is the Singapore Cremation Memorial, which remembers some 800 casualties, mostly Indian soldiers, whose remains were cremated in accordance with their religious beliefs.12

The panel at the western end of the Singapore Memorial, known as the Singapore (Unmaintainable Graves) Memorial, is dedicated to more than 250 casualties who had died in campaigns in Singapore and Malaya, but whose known graves in civil cemeteries could not be assured maintenance by the CWGC and which could not be transferred to Kranji due to religious reasons.13 Nearby, the Chinese Memorial in Plot 44 marks a collective grave for 69 Chinese servicemen who were killed by the Japanese in February 1942.

Soldiers of the Last Stand

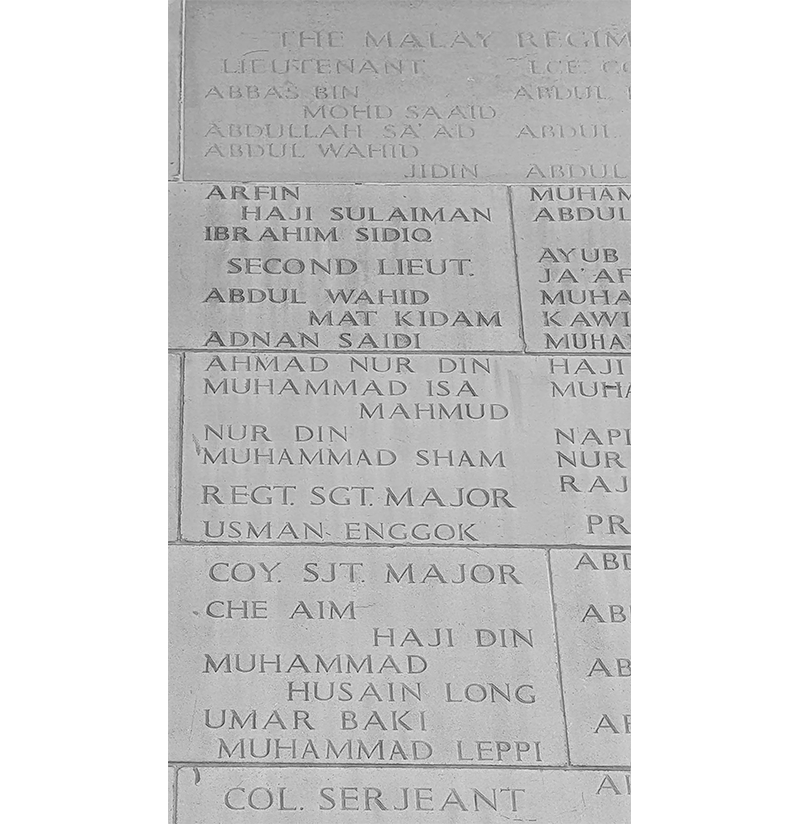

A total of 264 soldiers from the Malay Regiment are honoured at the Kranji War Cemetery. During the Battle of Singapore, the Malay Regiment – comprising some 1,400 men in two battalions – were part of the 1st Malaya Brigade tasked to defend Pasir Panjang on the southwestern part of the island.14

From 10 to 12 February 1942, Japanese forces captured the strategic Bukit Timah area, including access to supply dumps and reservoirs, tightening their grip around the city. With Bukit Timah lost, Allied troops were ordered to retreat behind the final defence perimeter that stretched from Pasir Panjang Ridge (now Kent Ridge) on the western end to Kallang in the east. This set the stage for the last, desperate battle between the men of C Company of the Malay Regiment’s 1st Battalion against the 18th Division of the Imperial Japanese Army at Bukit Chandu on Pasir Panjang Ridge on 14 February.

The Battle of Pasir Panjang commenced on the morning of 13 February with intense Japanese bombardment of the Malay Regiment’s positions. C Company managed to hold onto Pasir Panjang village despite being heavily outnumbered. At midnight, C Company evacuated to a new position at Bukit Chandu.15 To their left was B Company, which guarded the approach to Buona Vista village, while D Company covered the Labrador area on their right. C and D companies were separated by a deep drain flowing with oil that had been set ablaze by the enemy’s bombing of Normanton Oil Depot on 10 February.16

In the early afternoon of 14 February, the Japanese sought to infiltrate C Company’s position by disguising themselves as Punjabi soldiers. However, the deception was foiled and when the soldiers neared, C Company opened fire, killing and injuring 22 Japanese soldiers and driving the rest into retreat.17 Two hours later, the Japanese returned in greater numbers and overwhelmed the men of C Company, who found themselves sandwiched between enemy troops that had overrun B Company on one side, and a wall of fire on the other.

C Company Commander Captain H. R. Rix (plot 11, row D, headstone 1)18 gave orders to defend the position and fought valiantly, inspiring his men to do the same. Rix’s body was retrieved along with 12 other Malay Regiment soldiers at the site of their last stand. In another platoon, Lieutenant G.F.D. Stephen died leading a bayonet charge on the enemy after many of his men had been killed or wounded.19 His remains were never found and Stephen’s name is inscribed on Column 114 of the Singapore Memorial.20

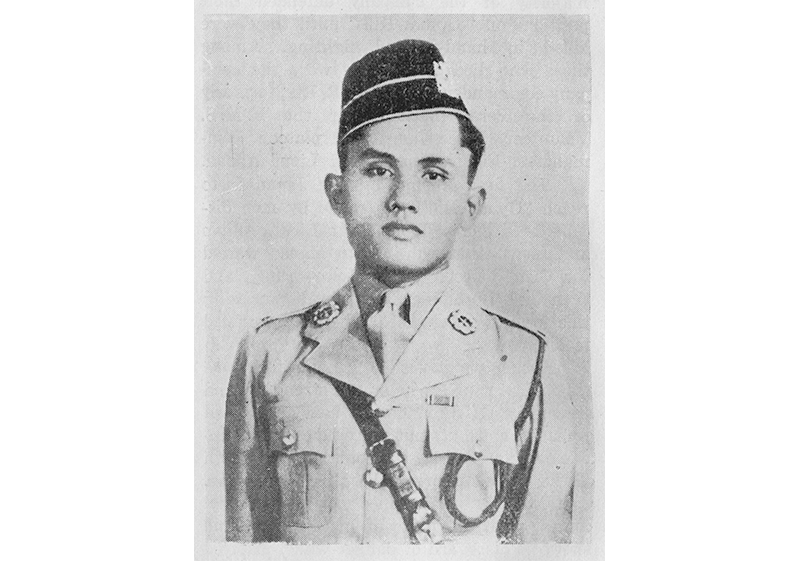

Second Lieutenant Adnan Saidi of C Company, who was himself badly hurt, exhorted his platoon to fight till the end, exemplifying the motto that he had chosen for them: Biar putih tulang, jangan putih mata, a Malay saying that is the equivalent of “death before dishonour”.21 After taking Bukit Chandu, the Japanese troops set about capturing and executing the surviving members of C Company, including Adnan. According to eyewitness accounts, Adnan was shot and bayoneted to death. His body was hung upside down from a tree and the Japanese forbade its removal for burial.22

In total, the Malay Regiment lost 159 lives (six British officers, seven Malay officers and 146 other ranks) during the battle at Pasir Panjang. Adnan and 26 other Malay soldiers who died during that battle, and whose bodies were never recovered, are commemorated on Columns 385 to 390 of the Singapore Memorial.23

The Commandos of Jaywick and Rimau

Among those buried in Kranji is Lieutenant Colonel Ivan Lyon of the Gordon Highlanders (a line infantry regiment of the British Army that existed from 1881 to 1994). In September 1943, Lyon, described as a “cool-headed, icy-calm and professional soldier”, led a team of 14 Australian and British commandos from Allied Z Special Unit in Operation Jaywick, a bold mission to sabotage Japanese ships in Singapore’s Keppel Harbour.24

On 2 September, the commandos departed Exmouth Harbour, Western Australia, in a captured Japanese fishing vessel, the Kofuku Maru. It had been repurposed and renamed Krait, after the small but deadly snake found in tropical Asia. Disguised as local fishermen, the men ditched their uniforms for sarongs and painted their bodies brown.25

Around two weeks later, on 18 September, Lyon and five operatives disembarked at Pulau Panjang in the Riau Islands. On 24 September, Lyon and his men set up on Pulau Subar, an uninhabited islet that served as an ideal observation post.26

Two nights later, the raiding party slipped undetected into Keppel Harbour and attached limpet mines (a type of naval mine attached to a target by magnets) to several Japanese ships.27 The charges went off on the morning of 27 September, reportedly sinking or severely damaging seven Japanese transport vessels, which amounted to some 37,000 tonnes of shipping. All 14 commandos managed to return safe and sound to Australia on 19 October 1942, 48 days after their journey began.28

Convinced that the attack was masterminded by internees at Changi Prison, the Kempeitai (Japanese military police) mounted a raid on the prison cells on 10 October 1943, leading to the arrest and torture of 57 innocents, 15 of whom died. This became known as the Double Tenth Incident.29

Another raid – the ill-fated Operation Rimau – was planned the following year. The codename was inspired by the tattoo of a Malayan tiger (harimau is “tiger” in Malay) that Lyon had on his chest.30 This time, a larger team of 23 Z Special Unit commandos led by Lyon were dropped off via submarine in the Riau Islands. There, they seized a local fishing boat, the Mustika, and sailed it towards Singapore. The original plan was for the men to use motorised submersible canoes, known as “Sleeping Beauties”, to plant limpet mines on Japanese ships in Keppel Harbour once again.31

However, disaster struck as a Japanese patrol boat spotted and challenged the Mustika just an hour before the raid was to commence on the afternoon of 10 October 1944. As a result, Lyon aborted the raid and ordered the destruction of the Mustika and the “Sleeping Beauties”. Unwilling to give up just yet, he and six others pressed on with the mission using folboats (collapsible canoes) instead. It is believed that the raiding party destroyed three Japanese ships on 11 October before scattering.32

The Japanese caught up with the commandos and in the clashes that ensued, 13 men, including 29-year-old Lyon, were killed in action or succumbed to injuries while in captivity. Lyon died on 16 October from an enemy grenade during a shootout on Pulau Soreh, an islet in the Riau Islands. He and two other commandos had fought off nearly a hundred Japanese soldiers for over four hours until their positions were discovered.33

The other 10 Rimau commandos were captured and incarcerated at Outram Road Prison in Singapore, tried for espionage, and sentenced to death by beheading on 7 July 1945.34 Their remains rest in a collective grave in Kranji (plot 28, row A, headstones 1–10).

Apart from the group of 10 men and Lyon, (plot 27, row A, headstone 14), another five are buried in separate graves (plot 23, row D, headstone 19 and 20; plot 32, row E, headstone 2 and 4; plot 27, row A, headstone 15). For the remaining seven, whose remains were not recovered, four have their names etched on the Singapore Memorial (Columns 117 and 118), and three are commemorated at the Plymouth Naval Memorial in England.35

Lest We Forget

On 2 March 1957, before some 3,000 guests which included veterans and families of the war dead, then Governor of Singapore Robert Black unveiled the dedication tablet on the Singapore Memorial, which bears the phrase “They Died For All Free Men”. Timed to drumrolls, the draped flags on the memorial’s columns pulled away, revealing the engraved names of more than 24,000 missing personnel. In his speech, Black said: “That simple sentence [“They died for all free men”] tells us why this multitude of men and women of differing faiths and races, but united in the service of their King, were faithful unto death.”36 Black’s words hark to the origins of Kranji War Cemetery as an imperial site honouring those who had made the ultimate sacrifice in the name of the then British Empire.37

The nearly four-hour long unveiling ceremony included the sounding of the Last Post, renditions of Lochaber No More and Reveille, the singing of hymns, followed by prayers from representatives of the Hindu, Muslim, Buddhist and Christian faiths. As Governor Black and selected guests were laying wreaths at the foot of the Cross of Remembrance, an elderly woman in a worn samfoo broke away from the crowd and stumbled towards them, sobbing loudly.38

She was 81-year-old Madam Cheng Seang Ho, nicknamed the Passionaria of Malaya (after La Pasionaria of the Spanish Civil War). She had fought fiercely alongside her husband, Sim Chin Foo, at the Battle of Bukit Timah.39 His name was etched on Column 399 of the memorial being unveiled that morning.40 In January 1942, the pair had joined Dalforce – a volunteer army hastily recruited from the local Chinese community – even though they were already in their 60s at the time. While Madam Cheng survived the war, her husband was one of many who had died at the hands of the Kempeitai. Her anguish is a reminder of the emotional pain that survivors and families endure in the aftermath of the war. Built for the dead, Kranji is equally important as a place for the living to mourn and seek solace.

Today, memorial services are held twice annually. One service is held on the Sunday closest to Remembrance Day on 11 November, while the other is held on ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) Day on 25 April in honour of Australian and New Zealand soldiers.41

What began as a site of imperial memory has also evolved to take on new meaning as Singaporeans visit the cemetery as part of national education and historical tours. Interpreted through the lens of nation-building, the cemetery holds lessons on the importance of self-reliance and self-determination, as it commemorates locals who had contributed to the defence of Singapore during World War II and as the war marked the turning point towards decolonisation.42

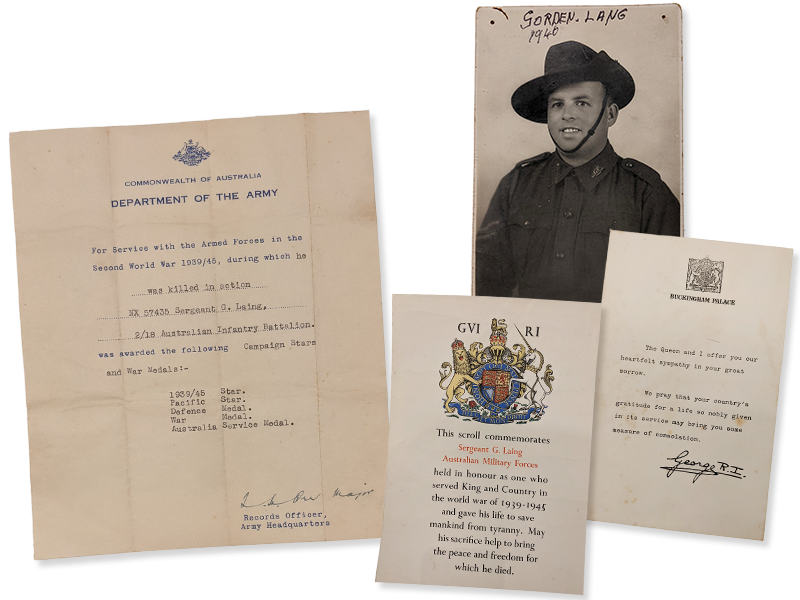

The National Library of Singapore holds a small collection of personal documents, war medals, photographs, postcards, letters and newspaper clippings relating to Sergeant Gordon Laing, who is commemorated on Column 119 of the Singapore Memorial.

Laing had served in the 2/18th Australian Infantry Battalion, part of the 22nd Brigade, 8th Australian Division. The 2/18th arrived in Singapore on 18 February 1941 and was immediately sent north to Port Dickson in Malaya for training. In March, they moved to Seremban, then to Jemaluang on the east coast in late August, before ending up in Mersing in early September. The battalion saw its first major action in an ambush on about 1,000 enemy troops at the Nithsdale Estate south of Mersing on 27 January 1942.

Laing is believed to have been killed in this engagement along with 82 other men on that fateful day. The battalion withdrew to Singapore following the Nithsdale ambush and was redeployed to defend the island’s northwestern coastline.

The items relating to Laing were donated by his grand-nephew, Dayne Cowan, to the library in 2019.

(Clockwise from top) Portrait of Sergeant Gordon Laing in uniform. This belonged to Laing’s sister, Ilena, whom Laing was very close to. There are holes on the corners as Ilena had tacked the portrait on her wall; Condolence letter (undated) and commemoration scroll from King George VI to Gordon Laing’s parents; Letter from the Commonwealth of Australia Department of the Army on the campaign stars and war medals posthumously awarded to Gordon Laing for his service during World War II. Collection of the National Library, Singapore.

REFERENCES

Australian War Memorial. “2/18th Australian Infantry Battalion.” Accessed 8 April 2022. https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/U56061.

Commonwealth War Graves Commission. “Sergeant Gordon Laing.” Accessed 8 April 2022. https://www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2136317/gordon-laing/.

Janice Loo is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include collection management and content development as well as research and reference assistance on topics relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia.

Janice Loo is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include collection management and content development as well as research and reference assistance on topics relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia.

NOTES

-

Justin Corfield and Robin Corfield, The Fall of Singapore: 90 Days: November 1941–February 1942 (Singapore: Talisman Publishing, 2012), 116–25. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 940.5425957 COR-[WAR]) ↩

-

“Corporal Raymond Lee Kim Teck,” Commonwealth War Graves Commission, accessed 31 Mar 2022, https://www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2228809/raymond-lee-kim-teck/. ↩

-

Romen Bose, Kranji: The Commonwealth War Cemetery and the Politics of the Dead (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2006), 21. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 940.54655957 BOS-[WAR]) ↩

-

Hamzah Muzaini and Brenda S. A. Yeoh, Contested Memoryscapes: The Politics of Second World War Commemoration in Singapore (London; New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2016), 98. (From National Library, call no. RSING 940.546095957 MUZ-WAR]) ↩

-

“Kranji War Cemetery,” Commonwealth War Graves Commission, accessed 8 April 2022, https://www.cwgc.org/visit-us/find-cemeteries-memorials/cemetery-details/2004200/kranji-war-cemetery/; Athanasios Tsakonas, “In Honour of War Heroes: The Legacy of Colin St Clair Oakes,” BiblioAsia 14, no. 3 (Oct–Dec 2018). ↩

-

Edwin Gibson and G. Kingsley Ward, Courage Remembered: The Story Behind the Construction and Maintenance of the Commonwealth’s Military Cemeteries and Memorials of the Wars of 1914–1918 and 1939–1945 (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1989), 66. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 355.1609 GIB) ↩

-

Gibson and Ward, Courage Remembered, 66. ↩

-

Wan Meng Hao, “More than Meets the Eye: Remembering the War Dead in Singapore,” in Spaces of the Dead: A Case from the Living, ed. Kevin Tan (Singapore: Ethos Books, 2011), 239. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 363.75095957 SPA) ↩

-

Athanasios Tsakonas, In Honour of War Heroes: Colin St Clair Oakes and the Design of the Kranji War Memorial (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2020), 178. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 725.94095957 TSA) ↩

-

“Kranji War Cemetery.” ↩

-

“Kranji War Cemetery.” ↩

-

Nor-Afidah A Rahman, Nureza Ahmad and Alec Soong, “Battle of Opium Hill,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published March 2021. ↩

-

Dol Ramli, “History of the Malay Regiment 1933–1942,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 38, no. 1 (207) (1965): 236. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Dol Ramli, “History of the Malay Regiment 1933–1942,” 238. ↩

-

Dol Ramli, “History of the Malay Regiment 1933–1942,” 239. ↩

-

“Captain Harry Rodway Rix,” Commonwealth War Graves Commission, accessed 8 April 2022, https://www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2821290/harry-rodway-rix/. ↩

-

Mubin Sheppard, The Malay Regiment 1933–1947 (Kuala Lumpur: Department of Public Relations, 1947), 18. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 355.31 SHE-[JSB]) ↩

-

“Second Lieutenant Geoffrey Francis Dixon Stephen,” Commonwealth War Graves Commission, accessed 8 April 2022, https://www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2072314/geoffrey-francis-dixon-stephen/. ↩

-

“Death Before Dishonour,” Straits Times, 8 December 1991, 2 (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Dol Ramli, “History of the Malay Regiment 1933–1942,” 239. ↩

-

Dol Ramli, “History of the Malay Regiment 1933–1942,” 242; “Second Lieutenant Adnan Bin Saidi,” Commonwealth War Graves Commission, accessed 8 April 2022, https://www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2529445/adnan-bin-saidi/. ↩

-

Lynette Ramsay Silver, Krait: The Fishing Boat That Went to War (Singapore: Cultured Lotus, 2001), 97, 195. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 940.545994 SIL-[WAR]) ↩

-

Bose, Kranji, 79–81; Petar Djokovic, “Krait and Operation JAYWICK,” Royal Australian Navy, accessed 8 April 2022, https://www.navy.gov.au/history/feature-histories/krait-and-operation-jaywick. ↩

-

Silver, Krait, 97–98; Heng Wong, “Double Tenth Incident,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published March 2021. ↩

-

Lynette Ramsay Silver, The Heroes of Rimau (Singapore: Cultured Lotus, 2001), 111. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 940.5426 SIL-[WAR]) ↩

-

Bose, Kranji, 82; Silver, Heroes of Rimau, 108–09, 111–12, 117–20, 133–34. ↩

-

Silver, Heroes of Rimau, 142–46, 283; Bose, Kranji, 82–83. ↩

-

Bose, Kranji, 83; Silver, Heroes of Rimau, 154–55. ↩

-

Silver, Heroes of Rimau, 213–16. ↩

-

Silver, Heroes of Rimau, 248. ↩

-

Terry Pillay, “A Living Tribute to Heroes Who Have No Graves,” Sunday Standard, 3 March 1957, 1 (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Hamzah Muzaini and Yeoh, Contested Memoryscapes, 98–99. ↩

-

Nan Hall, “Thoughts of the Past Move 81-Year-Old War Heroine to Tears,” Straits Times, 3 March 1957, 1; “Tragic Memories in a Garden of Peace,” Straits Times, 3 March 1957, 1; “A Moving Dedication at New Shrine,” Singapore Free Press, 2 March 1957, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“A Heroine Is Rewarded,” Straits Times, 25 July 1948, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Private Sim Chin Foo,” Commonwealth War Graves Commission, accessed 8 April 2022, https://www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2537430/sim-chin-foo/. ↩

-

Hamzah Muzaini and Yeoh, Contested Memoryscapes, 94. ↩

-

Hamzah Muzaini and Yeoh, Contested Memoryscapes, 94, 101–05. ↩