Subterranean Singapore: A Deep Dive into Manmade Tunnels and Caverns Underground in the City State

Singapore has been burrowing underground since the 19th century, but it was only after Independence that serious efforts were made to use subterranean space.

By Lim Tin Seng

Gleaming skyscrapers are a common sight in Singapore’s city centre as the country attempts to overcome the limitations of space by reaching skywards. Less obvious, but no less important, are Singapore’s efforts to take advantage of space underground.

Some of these underground structures are marvels of engineering. Located 150 m below Jurong Island, the Jurong Rock Caverns have been hailed as “Singapore’s deepest underground project”. Officially opened in September 2014, the nine-storey high caverns are designed to hold liquid hydrocarbons such as crude oil and condensate. These caverns have a total capacity of 1.47 million cubic metres, which is the equivalent of 600 Olympic-sized swimming pools.1

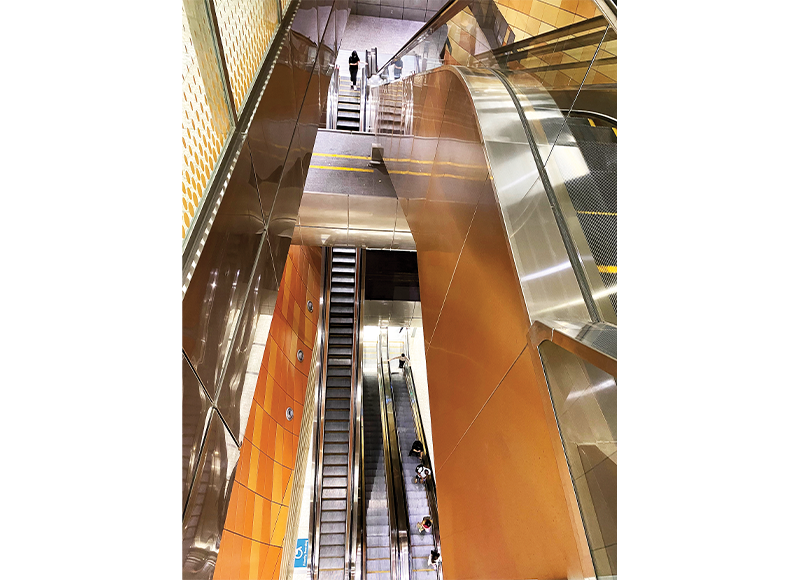

The Jurong Rock Caverns are not accessible to the public though. Those who wish to see what Singapore looks like in the depths of the earth don’t have to go far. All they need to do is take a trip on the Downtown Line to Bencoolen Station. At 43 m below the surface, this is currently Singapore’s deepest MRT station where the station platform is on level B6.2 (Spoiler alert: it looks like an MRT station platform.) Even a simple drive can take you far below the surface. One stretch of the 5-kilometre-long Marina Coastal Expressway is not merely underground, it is actually beneath the seabed.

Thanks to advanced technology, Singapore has been able to reach depths that would have been considered unimaginable only a few decades ago. However, burrowing underground is not a recent phenomenon here. Before the war, the British constructed tunnels under bunkers and forts to aid the defence of Singapore. Located in places such as Pasir Panjang, Sentosa and Labrador Park, these subterranean walkways were primarily used to store ammunition.3

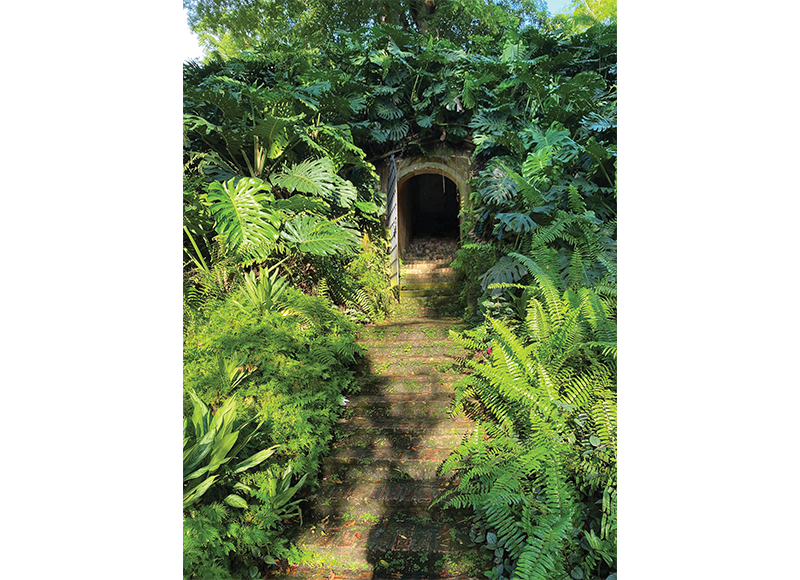

However, between 1936 and 1941, the British built a tunnel network under Fort Canning Hill that was different from the rest. Known today as the Battlebox, the 9-metre-deep maze was the command centre for the Malaya Command during World War II. Bomb- and flood-proof, the underground structure was “a self-containing centre” equipped with an electricity generator, a ventilation system and over 20 purpose-built rooms.4

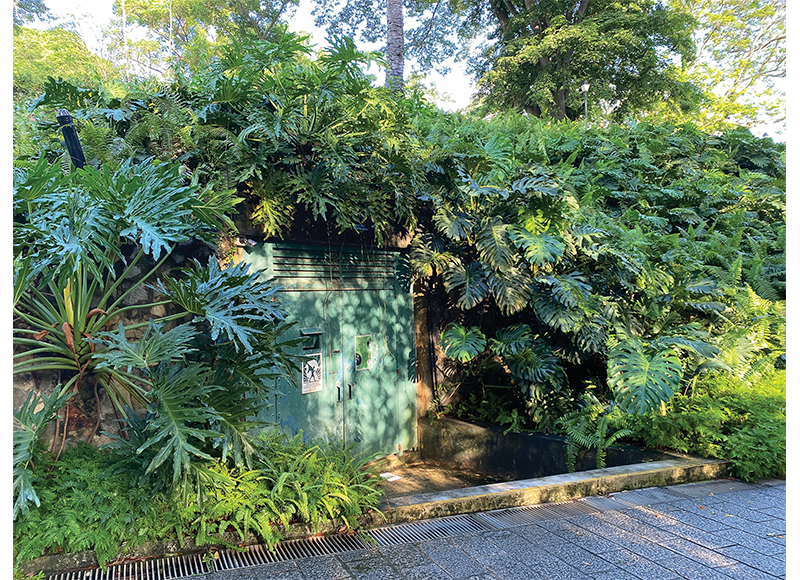

Interestingly, an even older underground military structure lies close to Battlebox. This is the sally port that was part of the old Fort Canning. When Fort Canning was built on top of the hill in 1861, it had a narrow, easily defended passageway called a sally port that burrowed from the fort on top of the hill and led to a path on the side of the hill, some 6 m below. The sally port allowed soldiers to enter and leave the fort without compromising the fort’s defence. The entrance to the sally port lies about 15 m from the entrance to the Battlebox.

While military installations may capture the imagination, it is probably accurate to say that in the pre-war years, the island’s underground spaces were mainly used for the laying of utilities. Comprising power transmission cables, gas pipes, sewerage pipes, telephone lines and water mains, these were placed in the ground by the Singapore Municipality “to keep them out of sight” as well as to protect them from elements and human-inflicted damages.5

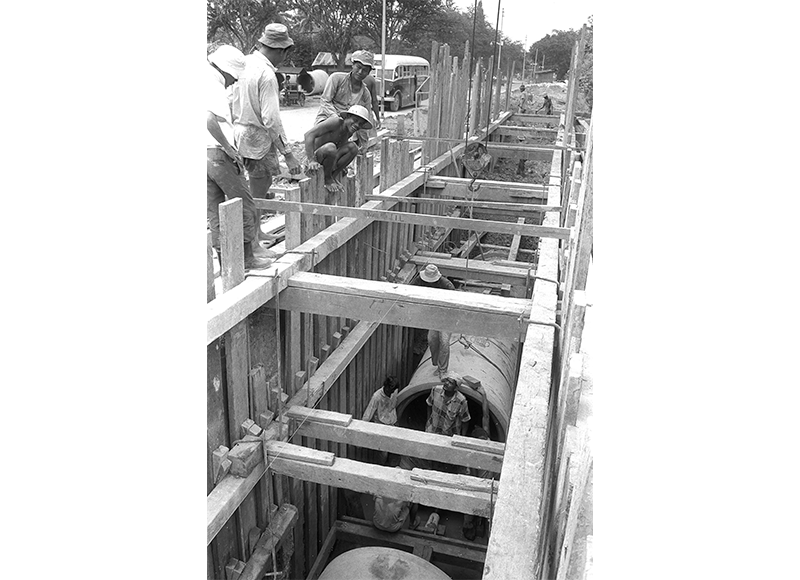

One of the earliest underground utilities laid was the water mains of MacRitchie Reservoir. Built in the late 1870s to replace an old brick conduit, these 0.6-metre cast iron pipes conveyed water from the reservoir to the town of Singapore via Thomson Road.6 To lay the water mains, the Municipality used the conventional trenching method where a trench was dug for the pipes before being filled back in. (This method was also deployed for other underground utilities projects including the island’s first sewerage pipes in the 1910s.7)

Laying these pipes was not an easy task. The municipality encountered “considerable difficulties” as the “pipes have had to be laid mostly in soft, water-logged ground which necessitated substantial timbering to trenches, continuous pumping, and a considerable amount of shoring to buildings”.8

These projects were also not popular because of the inconvenience the digging created on the surface, especially when it involved digging up roads. As the Straits Times noted in 1928: “So long as the Municipality continue to extend the water, electricity, and sanitation services throughout the city, so long will the invaluable Tamil labourer continue to obstruct the public roads, and so long will disgruntled members of the public half-seriously assert that the Municipality dig holes in the roads for the sheer fun of doing it.”9

Today, there are over 5,700 km of underground water mains in Singapore, compared to 1,300 km in 1958. During the same period, underground power transmission cables have also increased from a mere 82 km to more than 11,500 km. The story is the same for underground sewerage pipes network, which have increased in length from 423 km to 3,600 km.10

Moving Beyond Underground Utilities: Mass Rapid Transit

The post-war years saw the beginnings of an effort to move structures underground (as opposed to just utilities). In 1965, Singapore opened its first underground car park. Located at Raffles Place, the 127 m by 27 m structure accommodated up to 150 vehicles and was linked to the basement of Robinsons department store via an underground walkway.11 However, it was not until 1982 when Singapore started building the Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) system that the country began to use its underground spaces on a grander scale.

The initial MRT network was first launched in 1987 and completed in 1990. It had 42 stations and covered a total length of 67 km, of which 48 km are aboveground while the remaining 19 km are underground.

Given that this was Singapore’s first major effort at tunnelling underground, there were issues. In November 1985, there were several cave-ins along Scotts Road due to the alluvial nature of the soil there.12 Tunnelling works under Robinson Road also had to be halted the following month when the boring machine encountered soft marine clay. Nonetheless, these problems were resolved through engineering ingenuity such as using compressed air to hold up the soft texture of the soil, and injecting a high pressure mixture of cement and water to solidify soft marine clay.13

Over subsequent decades, the acquisition of new technical know-how on tunnelling has enabled lines such as the North-East Line, Circle Line, Downtown Line and Thomson-East Coast Line to be constructed entirely underground.

Tunnelling underground is not easy because of challenging soil conditions that could be “as soft as toothpaste, mixed with giant hard rocks”. At other times, the tunnels had to be dug to depths of up to 14 storeys in order to circumvent existing underground infrastructure such as utility pipes and previously constructed MRT lines. Engineers even had to divert part of the Singapore River and Eu Tong Sen Canal to allow tunnelling works to be carried out safely for the Downtown and North-East lines respectively.14

While all construction work is dangerous, there are additional dangers to working underground as the Nicoll Highway collapse on 20 April 2004 has shown. Four men were killed when the tunnel they were working on as part of the Circle Line collapsed. The collapse caused a wide section of Nicoll Highway to cave in, resulting in blackouts in surrounding areas. The body of foreman Heng Yeow Pheow was never found.15

For large infrastructure works such as public transport rail lines, the Tunnel Boring Machine (TBM) is used. Tunnelling using a TBM is made up of two phases. During the excavation phase, the TBM will burrow through the ground using its robust cutters like a mechanical mole. The crushed soil and rocks are then removed from the tunnel. The second or the “ring-building” phase will take place after the TBM has tunnelled through 1.4 m of ground. Here, segments of prefabricated reinforced concrete are lowered into the tunnel before being put up against the wall using hydraulic equipment and bolted into place to form a ring. This ring will be the platform for the underground project to be carried out.16

Currently, the three most common types of TBMs used in Singapore are the Slurry Shield TBM, the Earth Pressure Balance TBM and the Rectangular TBM. The slurry shield TBM acts like a powerful blender with a cutterhead filled with bentonite slurry that can stabilise the tunnel face as it bores through the soil. With the Earth Pressure Balance TBM, the materials dug out during tunnelling are used to support the tunnel face for the TBM to carry out its task. Finally, the Rectangular TBM features a rectangular instead of a circular cutterhead so that a rectangular tunnel can be constructed underground. These machines are enormous. The Rectangular TBM, for example, measures 5.6 m by 7.6 m.17

Road Tunnels and Expressways

While the initial MRT system was being built, Singapore also embarked on another underground transportation project comprising a 700-metre tunnel linking Bukit Timah Road to Cairnhill Circle, a 1.7-kilometre tunnel from Kramat Road to Chin Swee Road and a three-storey underground interchange with five slip tunnels at Clemenceau Avenue. These tunnels became part of the 15.5-kilometre Central Expressway (CTE), which was completed in 1991 and connects the city centre to housing estates such as Toa Payoh, Bishan and Ang Mo Kio.18

As the project was carried out in the middle of the densely populated city area under various soil conditions, the excavation and tunnelling work “demanded a high level of technical expertise and skill”. Six different types of temporary retaining walls had to be erected along the route to hold back the soil, and noise and vibration monitoring instruments were attached to about 40 buildings located within 50 m of the excavation sites. The Singapore River also had to be dammed in stages over a period of two years for construction to be carried out.19

Lessons learned from these projects are applied to the construction of more road tunnels along expressways like the Kallang-Paya Lebar Expressway (KPE) and the Marina Coastal Expressway (MCE), as well as arterial roads such as Fort Canning Tunnel, Woodsville Tunnel and Sentosa Gateway.

The MCE, in particular, was especially challenging to build. At the opening ceremony of the MCE in December 2013, then Minister of State for Transport and Finance Josephine Teo noted that the 5-kilometre-long expressway was the “toughest tunnelling project the Land Transport Authority (LTA) has ever undertaken”. Digging through reclaimed land, some of the soil was described as being “like peanut butter”, while a 420 m segment of the expressway had to be built beneath the seabed. That segment is just 130 m from the Marina Barrage, which added to construction difficulties as the barrage would regularly discharge water when it rained heavily, making the environment unpredictable.20

Today, at least 10 percent of Singapore’s roads are located underground. This figure will grow in the future as the 21.5-kilometre North-South Corridor (NSC) – slated to be completed in 2027 – will have a vehicular expressway underground and a public transport corridor above. Besides the NSC, there will also be more underground arterial roads, especially in upcoming housing estates like Tengah. Tengah is designed to have Singapore’s first car-free town centre, with roads running underground to free up space above for pedestrians and cyclists.21

Underground Pedestrian Networks

Other than an underground road network for vehicles, there are also underpasses for pedestrians built since the late 1960s.22 Initially, pedestrians found these underpasses “inconvenient” or “eerie” to use, as the New Nation reported in 1981: “[S]ome [pedestrians] shrugged and said they didn’t know where the underpasses were. Others exclaimed: ‘Aiyah, so inconvenient!’. Some spoke of the eerie feeling walking alone in an underpass, especially at night. ‘What if something or someone pounced at you from behind?’ one pedestrian asked.”23

Following the release of the Development Guide Plan for the new Downtown Core in 1996 that proposed turning underpasses into pedestrian malls, the first of such malls, CityLink Mall, was completed in 2000. Stretching some 350 m, the mall offers about 65,000 sq ft (6,039 sq m) of retail space, and links City Hall MRT Station and Raffles City to Marina Centre, Suntec City and the Esplanade. With its high ceilings, wide walkways and strategically placed skylights to allow natural light to stream in, these design elements strive to achieve an aboveground effect so “it doesn’t feel like an underground mall at all”.24 In 2010, a second underground pedestrian mall, the 179,000-square-foot (16,630 sq m) Marina Bay Link Mall, was built. It links One Raffles Quay with the Marina Bay area.25

Going Even Deeper

In the early 2000s, Singapore embarked on a new method to lay underground utilities. Known as the Common Services Tunnel (CST), this tunnel system conveys telecommunication cables, power lines and potable water to buildings in the Marina Bay financial district. The CST also houses pipes that supply chilled water to buildings for their air-conditioning needs as well as pneumatic tubes for refuse collection.

The 5.7-kilometre CST is “as big as two MRT tunnels” and its construction, which began in 2001, was met with “immense” challenges. To avoid existing underground infrastructure such as MRT lines, and pier and wharf structures buried under reclaimed land, engineers had to tunnel at depths of up to 20 m underground. At one point, they even had to dig through a 1.5-kilometre-long breakwater of solid rock dating back to the colonial era. Operational since 2006, the CST freed up space above, saved costs and reduced carbon emissions.26

Then there is the Transmission Cable Tunnel, which has been described as one of the world’s deepest electricity supply projects, and completed in 2018. Located at a depth of between 60 m and 80 m underground (compared to underground MRT tunnels which are 30 m to 40 m deep), the project comprises three tunnels – North-South, East-West and Jurong Island-Pioneer Tunnels. Ranging from a diameter of 6 to 11 m each, these tunnels can house the entire nation’s 500 km of extra-high voltage cables with the capacity to hold another 700 km more in the future. These tunnels allow the easy monitoring and replacement of cables with minimal disruption to traffic and the lives of Singaporeans.27

The Deep Tunnel Sewerage System (DTSS) is another underground utilities project that requires engineers to dig deep and tunnel through difficult soil conditions. Conceived in 1997, the DTSS “uses deep tunnel sewers to convey used water by gravity to centralised water reclamation plants”. Currently, the more than 100-kilometre-long DTSS serves the northern and eastern parts of Singapore through a network of sewers that are linked to two deep tunnel sewers. With diameters of up to 6 m, the two deep tunnel sewers had to be placed at a depth of up to 55 m underground.28 Phase 1 was completed in 2008, but phase 2 is still under construction. It is slated to be completed in 2025.29

The Underground Ammunition Facility (UAF), completed in 2008, is the country’s “first cavern development” and “the world’s most modern underground ammunition depot”. It took 10 years to build and is located under the old Mandai Quarry at an undisclosed depth. By storing ammunition in the UAF, this has helped free up about 300 ha of land, or the equivalent of 400 football fields.

Besides saving land, the use of automation and technology reduced manpower operational needs by 20 percent compared to a traditional depot, and insulation by the granite caverns also cut the energy required for cooling by half. This paved the way for the Jurong Rock Caverns project, which has enabled Singapore to free up some 60 ha of land, or the equivalent of 70 football fields, for other development works.30

What Lies Beneath?

In the decades ahead, it is very likely that Singapore will intensify its underground efforts. To prepare for this, the State Lands Act and Land Acquisition Act were amended in 2015 to facilitate the use and development of underground space by clarifying the extent of underground ownership and the introduction of strata powers for the acquisition of a specific stratum of space.31

When Singapore adopted the 2019 Master Plan in November 2019 to guide the island’s development over the next 10 to 15 years, it laid out a number of key initiatives that are likely to transform the way Singaporeans are going to live on the island in the future. These include creating greener and more sustainable neighbourhoods as well as creating jobs closer to homes. The master plan also called for the increased usage of subterranean spaces through an “Underground Master Plan”. The idea is to use the space beneath for infrastructure such as pedestrian walkways, rail lines, utilities, warehousing and storage facilities. This way, the land above can be freed up for housing, community uses and greenery.32

In 2017, the Singapore Land Authority, in collaboration with the Singapore-ETH Centre, was tasked to map out a three-dimensional underground plan of the island in a project called Digital Underground to study how underground space can be used more efficiently and effectively. (This centre was established by ETH Zurich – a public research university in Switzerland – and Singapore’s National Research Foundation to develop sustainable solutions to global challenges). The plan will be an important asset to building owners, developers and town planners as it will provide a “realistic, digital representation of the physical world below”, including the accurate locations of subterranean infrastructure such as underground utilities and pedestrian walkways.33

As tunnelling technology improves and as initiatives such as the Digital Underground mature, Singapore is likely to pursue even more projects underground to free up valuable space on the surface.

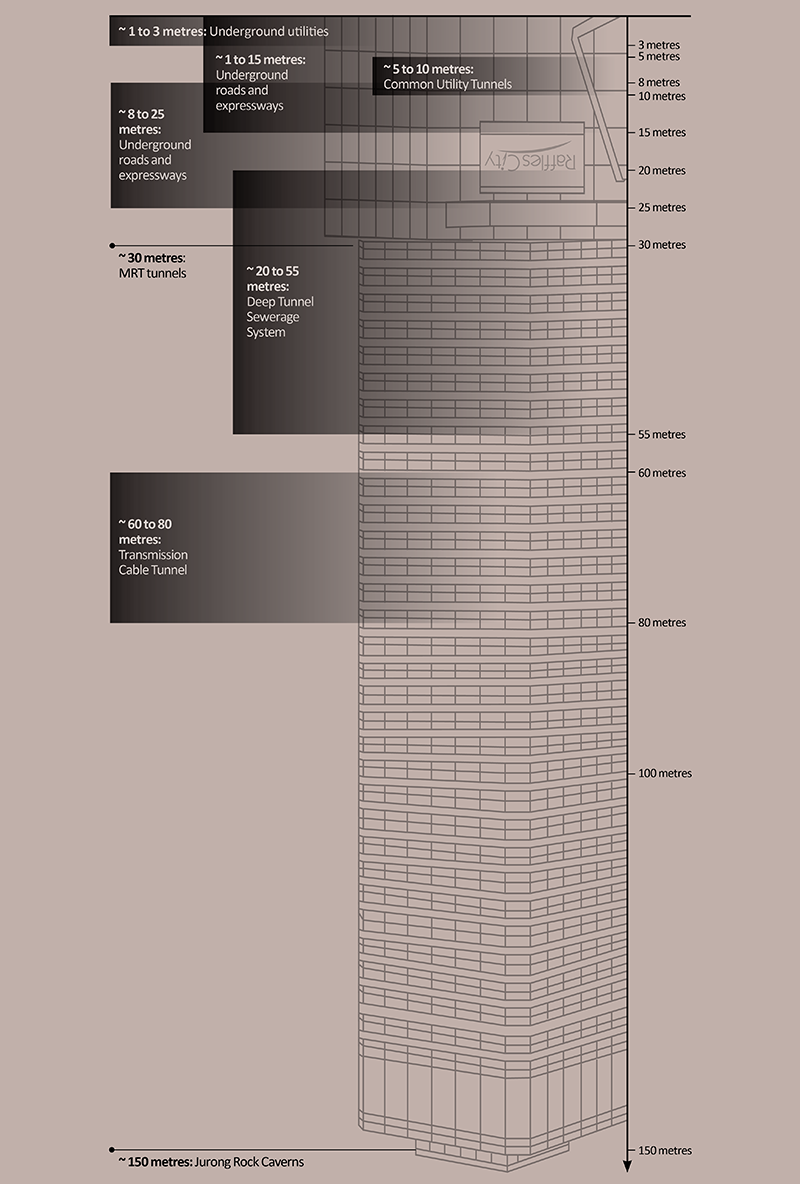

WHAT ARE WE STEPPING ON?

The 158-metre Raffles City Tower in the background shows how deep Singapore has been tunnelling underground.

The 158-metre Raffles City Tower in the background shows how deep Singapore has been tunnelling underground.

In the future, even more infrastructure will be moved underground to free up space above for development projects that will enhance the lives of Singaporeans. This infographic gives an idea of how Singapore’s subterranean spaces have been utilised so far.

REFERENCES

Feng, Zengkun, “Singapore Digs Deep for Ideas to Build Downwards,” Straits Times, 4 November 2013, 6. (From NewspaperSG)

Hong, Jose, “High-tech Sensors Protect Singapore’s New Electricity Supply Tunnels,” Straits Times, 19 December 2017. (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website)

“What Lies Beneath,” Straits Times, 11 February 2012, 15. (From NewspaperSG)

Lim Tin Seng is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013), Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He writes regularly for BiblioAsia.

Lim Tin Seng is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013), Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He writes regularly for BiblioAsia.NOTES

-

Janice Heng, “Digging Deep in Singapore for Space Solutions,” Straits Times, 17 June 2015, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/digging-deep-in-singapore-for-space-solutions; Teo Chee Hean, “Commissioning Ceremony of the Underground Ammunition Facility,” Mandai West Camp, 7 March 2008, https://www.dsta.gov.sg/latest-news/speeches/speeches-2008/commissioning-of-the-underground-ammunition-facility; “Underground Space,” Urban Redevelopment Authority, last updated 26 May 2022, https://www.ura.gov.sg/Corporate/Get-Involved/Plan-Our-Future-SG/Innovative-Urban-Solutions/Underground-space. ↩

-

“Factsheet: Downtown Line 3 to Open on 21 October 2017,” Land Transport Authority, 31 May 2017, https://www.lta.gov.sg/content/ltagov/en/newsroom/2017/5/2/factsheet-downtown-line-3-to-open-on-21-october-2017.html. ↩

-

“Singapore’s ‘Underground’,” Straits Times, 12 February 1992, 22. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Percival’s Fort Canning Bunker Re-opened,” Straits Times, 1 February 1992, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Pipe Manufacture in Singapore,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 2 January 1932, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Water-works,” Straits Times, 31 October 1902, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Sewerage Scheme,” Straits Times, 13 June 1913, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“$8,000,000 Sewerage Scheme Progresses,” Straits Times, 2 May 1940, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Occasional Notes,” Straits Times, 31 January 1928, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Colony of Singapore, Colony of Singapore Annual Report for the Year 1958 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1959), 222–31. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.57 SIN); Ahmad Zhaki Abdullah, “Smartphones, Floating Balls and Monitoring Sensors: How Singapore Is Going High-tech in Detecting Water Leaks,” Channel NewsAsia, 8 November 2020, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/high-tech-detecting-water-leaks-533736; “Protecting Our Underground Network,” SP Energy Hub, 11 July 2019, https://www.spgroup.com.sg/about-us/energy-hub/reliability/protecting-our-underground-network; Ng Keng Gene, “S’pore’s Strategies to Reduce the Likelihood of Heavy Flooding,” Straits Times, 23 April 2021, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/environment/spores-strategies-to-reduce-the-likelihood-of-heavy-flooding. ↩

-

“A Bird’s-eye View of Raffles Place Park,” Straits Times, 4 November 1965, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Scotts Road Once a River,” Straits Times, 9 November 1985, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Raise Tunnel Pressure, MRT Builders Told,” Straits Times, 28 December 1985, 12. (From NewspaperSG); Singapore Mass Rapid Transit Corporation, Stored Value: A Decade of the MRTC (Singapore: Mass Rapid Transit Corporation, 1993), 37. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 388.42095957 SIN) ↩

-

“Downtown Line,” Land Transport Authority, last updated 23 August 2021, https://www.lta.gov.sg/content/ltagov/en/getting_around/public_transport/rail_network/downtown_line.html; Leong Chan Teik, Getting There: The Story of the North East Line (Singapore: Land Transport Authority, 2003), 68–72. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 625.4095957 LEO) ↩

-

Amanda Phoon, “10 Years Ago,” Straits Times, 22 April 2014, 6; “Nicoll Highway Opens After $3M in Repairs,” Straits Times, 5 December 2004, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“What Lies Beneath: Meet LTA’s Digging Machine,” Land Transport Authority, 28 January 2022, https://www.lta.gov.sg/content/ltagov/en/who_we_are/statistics_and_publications/Connect/TBMs.html. ↩

-

“What Lies Beneath: Meet LTA’s Digging Machine”; Ministry of the Environment, Annual Report, 1981 (Singapore: Ministry of Environment, 1982), 23. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 354.5957008232 SMEAR); “Going Underground,” New Nation, 1 September 1981, 8; “Tunnel Mission,” Straits Times, 1 April 2015, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“It Includes First Underground Road Tunnels in S’pore,” Straits Times, 11 May 1991, 22; “CTE Project Completed,” Straits Times, 11 May 1991, 22. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“It Includes First Underground Road Tunnels in S’pore”; “CTE Tunnels Ready Before Year’s End,” Business Times, 4 January 1991, 24. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Josephine Teo, “Opening Ceremony of Marina Coastal Expressway,” Ministry of Transport, 28 December 2013, https://www.mot.gov.sg/news/speeches/Details/Speech-by-Mrs-Josephine-Teo-at-the-Opening-Ceremony-of-Marina-Coastal-Expressway-on-28-December-2013; “PWD Engineers Go Abroad to Study Underground Roads,” Business Times, 12 April 1990, 2; Fadzil Hamzal and Cel Gulapa, “A Highway under the Sea,” New Paper, 23 December 2013, 16–17. (From NewspaperSG); “Marina Coastal Expressway Opens,” Today, 29 December 2013, https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/marina-coastal-expressway-opens. ↩

-

Sherlyn Seah, “Land Transport Master Plan 2040: Faster Journeys for Cyclists, Bus Passengers at Priority Corridors,” Today, 25 May 2019, https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/land-transport-master-plan-2040-faster-journeys-cyclists-bus-passengers-priority-corridors; “North-South Corridor,” Land Transport Authority, last updated 10 March 2022, https://www.lta.gov.sg/content/ltagov/en/upcoming_projects/road_commuter_facilities/north_south_corridor.html; Kenneth Cheng, “Tengah to Get S’pore’s First Car-free Town Centre,” Today, 8 September 2016, https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/tengah-get-spores-first-car-free-town-centre; Oscar Holland, “Singapore Is Building a 42,000-home Eco ‘Smart’ City,” CNN, 2 February 2021, https://edition.cnn.com/style/article/singapore-tengah-eco-town/index.html. ↩

-

“Neon Lights and Ads to Lure Pedestrians Under,” New Nation, 11 June 1981, 12/13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Nancy Koh, “Going Underground,” New Nation, 11 June 1981, 12/13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Colin Tan, “New Downtown Plan Unveiled,” Straits Times, 24 August 1996, 24; “Coming Soon: CBD With Below Ground Walkway,” Straits Times, 22 November 1997, 7; Teo Pau Lin, “Underground Mall to Open,” Straits Times, 17 June 2000, 2; Tan Su Yen, “Shopping Goes Subterranean,” Business Times, 7 July 2000, 37. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Karen Teng, “Shopping Underground,” Straits Times, 29 September 2010, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Grace Chua, “Services Tunnel Overcomes Obstacles,” Straits Times, 12 August 2012, 16. (From NewspaperSG); “Marina Bay: A Vision and the Backbone,” Urban Redevelopment Authority, 5 July 2018, https://www.ura.gov.sg/Corporate/Resources/Ideas-and-Trends/Marina-Bay-vision-backbone; “Marina Bay District Cooling System,” SP Group, accessed 14 June 2022, https://www.spgroup.com.sg/sustainable-energy-solutions/our-low-carbon-solutions/cooling-and-heating; Liyana Othman, “World’s Biggest Underground District Cooling Network Now at Marina Bay,” Today, 3 March 2016, https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/plant-underground-district-cooling-network-marina-bay-commissioned. ↩

-

Jose Hong, “Singapore’s Deepest Tunnel System Almost Ready, Will Ensure Reliable Electricity Supply,” Straits Times, 19 December 2017, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/singapores-deepest-tunnel-system-close-to-completion-will-ensure-reliable-electricity; “Electricity Cable Tunnel Project,” SP Group, accessed 14 June 2022, https://www.spgroup.com.sg/cable-tunnel/Home.html. ↩

-

Siau Ming En, “Construction Begins for S$6.5 Billion, 100km Superhighway for Used Water,” Today, 20 November 2017, https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/construction-begins-s65-bn-superhighway-used-water. ↩

-

“Deep Tunnel Sewerage System: Phase 2,” PUB, last updated 23 November 2020, https://www.pub.gov.sg/dtss/phase2. ↩

-

Heng, “Digging Deep in Singapore for Space Solutions”; Teo, “Commissioning Ceremony of the Underground Ammunition Facility”; “Underground Space.” ↩

-

“Legislative Changes to Facilitate Future Planning and Development of Underground Space,” Ministry of Law (Singapore), 12 February 2015, https://www.mlaw.gov.sg/news/press-releases/legislative-changes-planning-development-underground-space. ↩

-

“Underground Space,” Urban Redevelopment Authority, last updated 14 June 2022, https://www.ura.gov.sg/Corporate/Get-Involved/Plan-Our-Future-SG/Innovative-Urban-Solutions/Underground-space; “Master Plan,” Urban Redevelopment Authority, last updated 14 June 2022, https://www.ura.gov.sg/Corporate/Planning/Master-Plan. ↩

-

Gerhard Schrotter and Rob van Son, Digital Underground: Towards a Reliable Map of Subsurface Utilities in Singapore (Singapore: Digital Underground, 2019), Singapore-ETH Centre, https://sec.ethz.ch/research/digital-underground.html. ↩