A Royal Wedding Gone Wrong: The 1820 Uprising in Riau That Brought the Bugis to Singapore

Celebrations during a royal wedding in Tanjung Pinang in 1819 led to a terrible misunderstanding that would change the course of history in Riau and Singapore.

By Benjamin J.Q. Khoo

At nine at night on 26 December 1819, the Dutch Artillery Captain G.E. Königsdorffer in Tanjung Pinang was startled by shots ringing out from the nearby Bugis kampong. Alarmed and determined to find out the cause, he dispatched a patrol from his fort. As the shots died into the silence of the night and the troopers marched out, little did he know that this was the beginning of a chain of events that would end with being shot in the shoulder, numerous dead and the flight of the Bugis across the Straits to the disputed settlement of British Singapore.

The Dutch Return to Riau

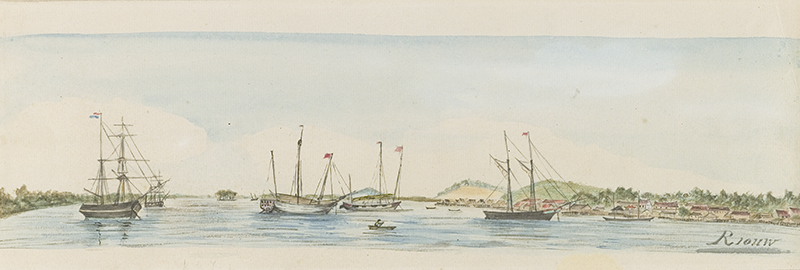

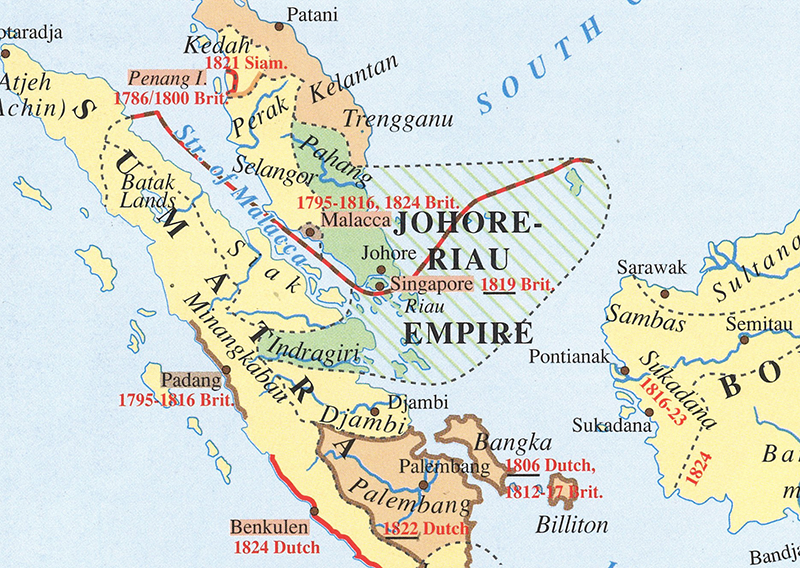

No such premonitions were apparent to Königsdorffer when the Dutch frigate Tromp dropped him in Tanjung Pinang on Bintan island.1 Sometime in November 1818, the Dutch had returned to their former possessions in the East Indies (Malay Archipelago) and were eager to renew their old alliances. Arriving in a show of military force on Pulau Penyengat, they promptly signed a treaty with the reigning Bugis Viceroy or Yang Dipertuan Muda Raja Jaafar, which was sealed with the stamp of Sultan Abdul Rahman Muazzam Shah of the Johor-Riau Sultanate. The flag of the Netherlands was raised on the island, and Königsdorffer was appointed Resident and Commandant over the small garrison of 150 men.

However, any notion of a quiet return was quickly dispelled. In February 1819, news came that a British party had landed on the nearby island of Singapore and established a trading post there.2 To find out more about this new settlement, Dutch Captain Cornelius P.J. Elout returned to Riau from Batavia (now Jakarta) in June 1819. Although he was there to implement the treaty that the Dutch had signed with the Bugis, Elout also took the opportunity while in Riau to measure the sentiment on the ground and reaffirm the allegiance of the royal court.3

As 1819 drew to a close, the East Indies seemed to be firmly in the hands of the Dutch. The new settlement of Singapore was precariously placed and badly defended. Its regnal conspirators sat uneasy while the agent who had provoked the occupation (namely Stamford Raffles) had decamped to Bencoolen (now Bengkulu) to nurse his ailing health. In diplomatic circles, angry protestations raised in Dutch letters caused an uproar and made the British authorities initially disavow Raffles’s schemes. The survival of Singapore and British plans to secure a base at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula hung in the balance.4

In Riau on the other hand, local loyalties were secured by treaty, money and timely intervention. Unfortunately for the Dutch, before the year was out, a terrible misunderstanding would turn the whole situation on its head.

Shots in the Night

Unbeknownst to Königsdorffer and his men in the nearby fort that fateful night, a huge celebration was taking place within the Bugis kampong. According to the Malay literary work, Tuhfat al-Nafis (Precious Gift), one of the Bugis chiefs, Arung Belawa,5 was getting married to his cousin Raja Fatima.6 The people of Tanjung Pinang and Pulau Penyengat had gathered together to celebrate the union, and the boisterous festivities were enlivened by the firing of shots, following Bugis custom and practice. Caught up in the fervour of the moment, the Bugis fired numerous shots in succession, the pops growing louder and more insistent, first with small, light shots, and finally with the thunder of a 12-pound cannon.

These were the shots heard by the Dutch in the fort.7 Feeling uneasy, Königsdorffer dispatched a military patrol under the command of a sergeant with the instruction to bring back someone who could enlighten them.

What happened in the Bugis kampong is not recorded. In any case, the sergeant and his men managed to arrest not one but five people, among them Raja Ronggik, the cousin of Arung Belawa, who was also one of the chieftains. These men gave themselves over civilly and went along with the Dutch. The Bugis men were then placed in a waiting room and this is when the dreadful misunderstanding occurred.8

Opinions of the exact trigger of the incident differ, but the accounts agree that the Bugis drew their krises first and struck. However, no one was absolutely certain as to why they had done so. According to the Tuhfat al‑Nafis, the sergeant had ordered that the Bugis men be disarmed of their krises, to which they refused. The soldiers then attempted to relieve them of their weapons. In the ensuing scuffle, a furious Raja Ronggik drew his kris and charged at the Dutch soldiers, prompting the other Bugis to follow. Other Dutch accounts state that it was the decision to put them in clinks that enraged them. This was akin to being treated like common criminals, which wounded their pride and sparked discontent on that humid night.9

Regardless of the trigger, the violence happened in a flash. The glints of the drawn krises saw the Dutch respond with rifle fire. A few bloody moments later, the bodies of the five Bugis men were on the ground: two lay severely wounded, and three were dead, the latter including Raja Ronggik. On the Dutch side, one was slain while five others were heavily injured. A routine inquiry had gone horribly wrong.

The Uprising

News of Raja Ronggik’s death spread like wildfire. The next day, the Dutch sought to reassure the incensed Arung Belawa that it was only a misunderstanding. However, his fury could not be quenched. Not only did he get his men to secretly shoot at Dutch patrols, he also sent spies and behaved very belligerently.10

Between the last days of 1819 and the first of the new year, almost two weeks of uneasy silence ensued. The suspense finally broke on 14 January 1820 when 400 Bugis launched a surprise attack on the house of the Dutch income-collector, Johan Hendrik Walbeehm. Why this site was chosen is unclear, but there were already hints of simmering discontent with the new taxes imposed by the Dutch.

The Bugis then took over the remaining Dutch fortifications on the beach and propped them up with their own defences. At the same time, they besieged Königsdorffer’s garrison which had suffered from years of neglect and was in a sorry condition. To bolster its strength, Königsdorffer had added a firm palisade fence with a cannon, but this was insufficient to repel the Bugis assault. The Bugis had also planned well; half the Dutch regiment had returned to Melaka for the change of guards, and the garrison thus had less manpower. With knowledge of the lay of the land, the Bugis chose an advantageous position, dug up the ground and built breastworks encircling the Dutch fort, all the while maintaining their assaults with cannon fire and cutting off Dutch access to supplies in preparation for a siege.11

Compounding this dire situation was a lack of authority in court. The sultan and yang dipertuan muda were in Lingga, leaving the Arab Tengku Syed behind to hold court in their absence. In the interim calm before the storm, Königsdorffer, having well apprised himself of the gravity of the situation, initially called twice or thrice daily on Penyengat in order to consult with this intermediary over the growing Bugis discontent.12

Tengku Syed did all he could to defuse the situation. He advised the Dutch to keep their correspondence to letters, to always go about with armed escorts, and even forestalled an assassination on Königsdorffer’s life by Belawa’s men.13 His other appeals were to the Bugis, with a slew of couriers dispatched to pacify Arung Belawa. But Arung Belawa could not be swayed.14

This siege lasted for 15 days until reinforcements for the beleaguered Dutch forces finally came from Melaka and Muntok (or Mentok). On 25 January, a war-brig arrived to augment Dutch defences in Riau, and the expected showdown erupted on 29 January. At dawn, Dutch ships opened fire at the Bugis and around one hundred Dutch soldiers broke the siege by attacking the batteries.15

In the tumult, Königsdorffer, who had bravely defended the small garrison while waiting to be relieved, was manning a six-pound cannon when he received two shots to his shoulder. Despite the Bugis putting up a brave fight, the outcome was decidedly one-sided. When the dust of battle had cleared, the Dutch side counted seven dead and 13 injured. For the Bugis, the count was brutally high: around 80 men, all slain.16

The Flight to Singapore

Immediately after the collapse of this uprising, the Bugis escaped in their boats and fled across the Straits for safety in the settlement of Singapore. This took place the following day, on 30 January. Bugis men, women and children emptied themselves from their houses and escaped via Riau Terusan, between Senggarang and Bintan, towards the island of Singapore.17

William Farquhar, Resident of Singapore at the time, counted almost 500 of them, arriving in a fleet of ships, leaving behind a Bugis kampong smouldering in ash. Farquhar was very pleased to offer them refuge, settling them along the Rochor River, which eventually became Kampong Bugis.18 Their arrival shifted the lucrative Bugis trade westwards, away from Dutch Riau and towards British Singapore. This proved a turning point in Singapore’s fortune. Besides the material gain, the British obtained added satisfaction in witnessing the troubles of the Dutch, whom they viewed as a rival.

“The Bugguese [Bugis],” wrote Farquhar to Raffles in March of the same year, “have lost all confidence in their [the Dutch] system of government”. Raffles gloated upon learning of the debacle. “They must now regret the wild ambition, which induced them to aim at such extensive sovereignty,” he replied in April 1820, “their empire is literally crumbling to pieces”.19

It was a sorry situation back in Riau, with many kampongs destroyed and Dutch fortifications in ruins. Anxiety was at a high and many feared that this was a sign of more trouble coming to pass. Several court nobles were disgruntled and made plans to flee. Similarly, the Chinese, who had worked in Riau and established their own settlements since the 18th century, also suffered much collateral damage. Those on Tanjung Pinang saw their kampongs go up in flames and most of the inhabitants were forced to decamp to Pulau Penyengat. The Dutch compensated the Chinese with 6,000 guilders to rebuild their houses. This expense was necessary to prevent them from following the Bugis in relocating to Singapore. However, it was not enough to prevent some from choosing this course.20

If in 1819, Riau seemed secure and prosperous, 1820 was the year in which the balance tipped irreversibly in Singapore’s favour. This influx of people, Bugis as well as Chinese, increased Singapore’s population, much to the chagrin of the Dutch who could only watch as the prized trade was diverted across the Straits.

The Aftermath

When hostilities ceased, the Dutch announced a general amnesty to get the Bugis to return and preserve the peace. Tengku Syed even offered to mediate between both sides.21 But both of these gestures were swiftly rebuffed by the Bugis in Singapore.

The Dutch then dispatched Lieutenant Paris de Montaigu to Singapore, bearing a letter for Farquhar to persuade him to hand over “the rebel prince Belawa”. Farquhar immediately shot the proposal down as “quite inadmissible”.22

The incident came to cause much reflection and consternation for the Dutch in the East Indies. Besides losing impetus to a developing Singapore, it also reflected the teething issues they faced in returning to local administration under much transformed political circumstances. In his reflections in 1828, Captain Cornelius P.J. Elout pinned the misunderstanding with the Bugis on Dutch “unfamiliarity with the language and customs of the natives”.23

Likewise, another Dutch military officer and traveller, Colonel Hubert Gerard Nahuijs, who made a voyage to Riau and Singapore around the year 1824, placed the blame squarely on “our officers, who were ignorant of the country’s ways and manners”, mistaking the firing of shots in marriage celebration as a sign of rebellion.24 In order to avoid such a fiasco from occurring again, Nahuijs encouraged the Dutch government to appoint experienced officers who understood local principles and customs.25

What became of Captain Königsdorffer? After being temporarily relieved of his duties as he recuperated from his injury, Königsdorffer was eventually replaced as Resident of Riau by Count Lodewijk Carel von Ranzow in 1821. This was not a slight on his abilities, and his discharge was duly celebrated with the feting of honours. For his leadership and bravery, Königsdorffer was awarded the Cross of the Legion of Honour. He was also recommended for the Military Order of William (Militaire Willems-Orde), one of the highest honours in the Netherlands.26

Finally, in all this, the Dutch did not lose sight of practical military concerns. The Bugis attack showed how badly Dutch bulwarks on Riau were in need of reinforcement. In place of the old, dilapidated garrison, a new fort was constructed: Fort Kroonprins. It rose from the hillock, but was fortified with a dry ditch, a wall of hewn stone with four bastions and a lunette.27 Looming like a panopticon over Riau, it was an impressive symbol of Dutch colonial power.28

Epilogue

Although Arung Belawa seemed to have settled quite comfortably in Singapore, he spent his time harassing Dutch ships, sporadically attacking gambier plantations in Riau and generally proving to be a nuisance.

In 1824, the Dutch finally succeeded in convincing Arung Belawa to return to Tanjung Pinang. Walbeehm, the Dutch income-collector, who somehow managed to escape with his life during the surprise Bugis attack in 1820, was credited with this persuasion, but much more enticing was the high monthly salary that the Dutch government promised to pay Arung Belawa – a pension sum of 500 florins.29

Arung Belawa and about 260 of his entourage sailed back across the Straits, comprising his family members, slaves and followers. They did not return to their former kampong but chose to establish their base across the bay, slightly beyond the confines of the Dutch presence there.30

However, the return of Arung Belawa and his people to Riau brought no evident contribution to its prosperity and trade. It was the Bugis traders whom the Dutch wanted, but they had chosen to remain behind in Singapore instead.31

The story after 1824 needs no further retelling. The Anglo-Dutch Treaty, inked between Britain and the Netherlands in London on 17 March 1824, formalised the division of the Johor-Riau Empire into British Malaya and the Dutch East Indies.

Riau – the successor to the Malay ports of old – and the Dutch residents who came after Königsdorffer were witness to its gradual peripheralisation, while its neighbour Singapore became one of the major trading nodes of the world.32 All this was set in motion by a misunderstanding across the Straits, arising from shots fired into the dark.

Benjamin J.Q. Khoo is a Research Officer at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute and a 2020/21 Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow at the National Library, Singapore. Studying the histories of the early modern world, his research focuses on networks of knowledge and diplomatic encounters in Asia.

Benjamin J.Q. Khoo is a Research Officer at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute and a 2020/21 Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow at the National Library, Singapore. Studying the histories of the early modern world, his research focuses on networks of knowledge and diplomatic encounters in Asia.NOTES

-

Elisa Netscher, De Nederlanders in Djohor en Siak, 1602 tot 1865 (Batavia: Bruining and Wijt, 1870), 257. ↩

-

Arnold Willem Pieter Verkerk Pistorius, Een Bezoek aan Singapore en Djohor: Eene Voordracht (s’-Gravenhage: Martinus Nijhoff, 1875), 9; C.M. Turnbull, A History of Modern Singapore, 1819–2005 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2009), 28–29. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 TUR-[HIS]) ↩

-

Netscher, De Nederlanders in Djohor en Siak, 258. ↩

-

Turnbull, History of Modern Singapore, 30. ↩

-

Arung Belawa was a Bugis from the royal house of Sidenreng in Celebes (Sulawesi). ↩

-

Raja Ali Haji ibn Ahmad, The Precious Gift (Tuhfat al-Nafis), trans. Virginia Matheson and Barbara Watson Andaya (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1982), 229–30. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5142 ALI) ↩

-

Raja Ali Haji ibn Ahmad, Precious Gift, 229–30. ↩

-

P.H. Van der Kemp, “De Commissiën van den Schout-Bij-Nacht C.J. Wolterbeek Naar Malakka En Riouw in Juli-December 1818 En Februari-April 1820” Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indië 51, no. 1 (1900): 49–50. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Willem Adriaan van Rees, Toontje Poland: Voorafgegaan door Eenige Indische Typen, vol. 1. (Arnhem: D.A. Thieme, 1867), 242. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RRARE 959.8 REE-JSB], accession no. B29032467K) ↩

-

Netscher, De Nederlanders in Djohor en Siak, 259–60; Van der Kemp, “De Commissiën van den Schout-Bij-Nacht C.J. Wolterbeek,” 50. ↩

-

Netscher, De Nederlanders in Djohor en Siak, 260; Raja Ali Haji Ahmad, Precious Gift, 230. ↩

-

Said Mohamad Tongko Zien, “Rapport van Tongko Said, afgezant van den Sulthan van Lingga en zijne Hoogheid den onderkoning van Riouw” (unpublished manuscript, 1824), 15. ↩

-

Said Mohamad Tongko Zien, “Rapport van Tongko Said, afgezant van den Sulthan van Lingga en zijne Hoogheid den onderkoning van Riouw,” 15–18. ↩

-

Raja Ali Haji Ahmad, Precious Gift, 230. ↩

-

Van der Kemp, “De Commissiën van den Schout-Bij-Nacht C.J. Wolterbeek,” 61–62. ↩

-

Netscher, De Nederlanders in Djohor en Siak, 261. ↩

-

Van der Kemp, “De Commissiën van den Schout-Bij-Nacht C.J. Wolterbeek,” 62. ↩

-

Turnbull, History of Modern Singapore, 33–34. ↩

-

Sophia Raffles, Memoirs of the Life and Public Service of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (London: John Murray, 1830), 444, 446. (From BookSG) ↩

-

Van der Kemp, “De Commissiën van den Schout-Bij-Nacht C.J. Wolterbeek,” 62–63. ↩

-

Gazeta de Lisbon, 153–313 (Terça-feira, 19 de Setembro, 1820) (Lisbon: Na Officina de Antonio Correa Lemos, 1820), 244. ↩

-

Van der Kemp, “De Commissiën van den Schout-Bij-Nacht C.J. Wolterbeek,” 65. ↩

-

Wolter Robert van Hoëvell, “Waarom Heeft Rio Als Vrijhaven Niet Met Singapoera Kunnen Mededingen?” in Tijdschrift Voor Nederlandsch-Indië 14 (1852): 415. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RRARE 382.71095981 HOE) ↩

-

Hubert Gerard Nahuys van Burgst, Brieven Over Bencoolen, Padang, het Rijk van Menangkabau, Rhiouw, Sincapoera, en Poelo-Pinang (Breda: F.B. Hollingérus Pijpers, 1826), 234. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RRARE 915.9804 NAH-[JSB]; accession no. B29268406D) ↩

-

Nahuys van Burgst, Brieven Over Bencoolen, 233. ↩

-

Van der Kemp, “De Commissiën van den Schout-Bij-Nacht,” 49, 58–59; A.R Falck, Ambts-Brieven van A.R. Falck, 1802–1842 (‘s Gravenhage: Van Stockum, 1878), 133. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RRARE 909.81 FAL; accession no. B29032462F) ↩

-

George François de Bruyn-Kops, “Sketch of the Riau-Lingga Archipelago”, Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia 9 (1855): 97. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RRARE 950.05 JOU; microfilm no. NL25797) ↩

-

Steven Adriaan Buddingh, Neêrlands Oost-Indië, vol. 3 (Amsterdam: Wed. J.C. van Kesteren en Zoon, 1867), 15. ↩

-

Netscher, De Nederlanders in Djohor en Siak, 261; Ota Atsushi, “The Business of Violence: Piracy around Riau, Lingga, and Singapore, 1820–40”, in Elusive Pirates, Pervasive Smugglers: Violence and Clandestine Trade in the Greater China Seas, ed. Robert J. Antony (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2010), 133. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 364.1336091646 ELU) ↩

-

Engelbertus de Waal, Onze Indische Financien: Nieuwe Reeks Aanteekeningen, vol.7 (‘s-Gravenhage: Martinus Nijhoff, 1884), 14. ↩

-

Netscher, De Nederlanders in Djohor en Siak, 262. ↩

-

Dianne Lewis, “British Policy in the Straits of Malacca to 1819 and the Collapse of the Traditional Malay State Structure”, in Empires, Imperialism and Southeast Asia: Essays in Honour of Nicolas Tarling, ed. Brook Barrington (Clayton, Victoria: Monash Asia Institute, 1997), 32. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 325.54 EMP) ↩