Neo Tiew: The Man Who Built Lim Chu Kang

The opening up of Lim Chu Kang owes much to the efforts of Neo Tiew, who helped clear the land and later became the headman of the area.

by Alvin Tan

Neo Tiew Estate is a small housing estate in Lim Chu Kang.1 It consists of three low-rise blocks of vacant flats, a disused market and food centre, and an abandoned children’s playground. The residents were resettled in the late 1990s and early 2000s and the estate is now used for training by the Singapore Armed Forces.

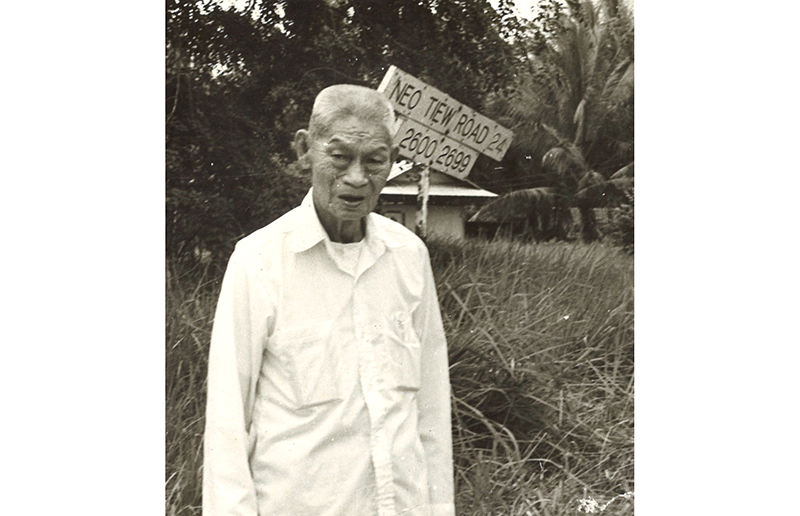

Neo Tiew Estate, and the nearby Neo Tiew Road, Neo Tiew Crescent and Neo Tiew Lanes 1, 2 and 3 are named after a remarkable man by the name of Neo Tiew (梁宙; 1884–1975).2 Neo played an instrumental role in the development of Lim Chu Kang. It is thanks to his energy and vision that the area was cleared and became used as farmland. While agriculture is no longer a large part of Singapore’s economy today, the Lim Chu Kang area has an important role to play in the country’s plans to become more self-sufficient in food. A century after Neo first began clearing the area, the impact of his work is still being felt.

A Meeting of Minds

It was 1914 and businessman Alexander W. Cashin (1876–1947) owned 800 acres of land in Lim Chu Kang that he wanted to develop.3 He needed someone honest and trustworthy, and with experience in land clearance and plantation management. He found that man in the person of Neo Tiew.4

Born in 1884 in Nan’an county in Fujian province, China, Neo left his impoverished hometown in 1897 at the age of 13 in search of a better life in Singapore. He worked in various odd jobs after he arrived and eventually ended up managing a rubber plantation in Selangor until 1912.

That was also the year when he took over his uncle’s brick-making business, Yuanshengfa, which was located on Holland Road. Through this business, Neo met Cashin, who was one of the customers Neo supplied bricks to. Cashin found Neo to be honest, hardworking and capable, and approached him to clear his land in Lim Chu Kang.5 In 1914, Neo took up Cashin’s offer and this decision put Neo on the path to reshaping the area.

Opening Lim Chu Kang

Neo approached the task like a military operation. Deploying 800 men to clear 800 acres of land was not simple. Getting to Lim Chu Kang, in the absence of roads from the town (and with only a sparse network of jungle tracks in the area itself), was a tedious undertaking that involved sailing from Telok Ayer to the Strait of Johor.6

With an advance party of eight men, Neo brought along boatloads of building materials. About 1.5 kilometres from their landing point, the team began clearing the secondary jungle and putting up huts, while spending their nights onboard their boats. After completing their temporary accommodation, Neo brought in the next wave of 40 men to augment his workforce. Over time, as the work advanced steadily inland, their beachhead became Neo’s command centre.

It took five years for the men to clear the land and reach the upper tributaries of Kranji River where Neo decided to build a jetty to take advantage of the river as a communications artery. They also planted large numbers of coconut trees, pineapple plants and later, rubber trees. (Neo’s methodical and systematic land clearance drew the attention of businessman Mirza Mohamed Ali Namazie, who approached Neo to clear 900 acres of his land in the area as well.7)

Building Lim Chu Kang

This was when Neo’s business took off. Together with Cashin’s gift of 60 acres of land, Neo expanded his own land to 200 acres, centred around Nam Hoe Village and the jetty he built. (The village was named after its most prominent landmark, the Nam Hoe provision shop that Neo had opened.8)

The Kranji River was Nam Hoe Village’s only connection to the outside world. To get to Woodlands Road, which was the most direct route to the town, one would first have to traverse by boat down the river and disembark at Jalan Nam Huat. This inaccessibility also cut the area off from the growing traffic that came when the Causeway opened in 1923.9

Neo lobbied the colonial government to build a road to connect the Lim Chu Kang area to the rest of the island.10 The government insisted on a co-payment model and left Neo to canvass and raise funds for this project. In total, more than $30,000 was raised for the 8-kilometre-long road.

On 4 October 1930, the Public Works Department opened a tender for the construction of “earthwork formation for new road at Lim Chu Kang”.11 By 1932, Lim Chu Kang Road was “open to within 1½ miles of the Johore Straits”.12

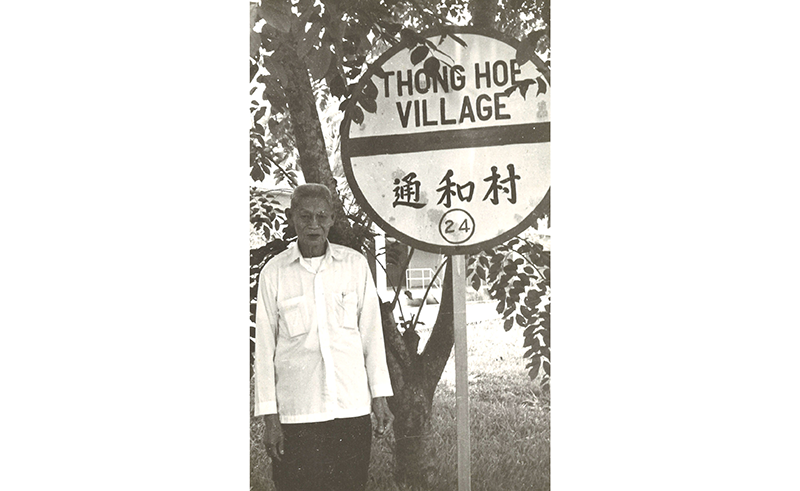

The new road provided the impetus for the founding of another village, Thong Hoe, which was named after yet another provision shop owned by Neo.13

Lim Chin Sei, who used to be a farmer in Lim Chu Kang, recalled in his oral history interview that the provision shop was the centre of village life, a meeting point and the place where Neo arbitrated and resolved disputes and quarrels. According to Lim, Neo loved to regale his audience with stories – there were no airs about him despite his wealth – and he frequently attended weddings and funerals, keeping his pulse on things. When it came to crime though, Neo was firm and no-nonsense, and the village thugs were afraid of him.14

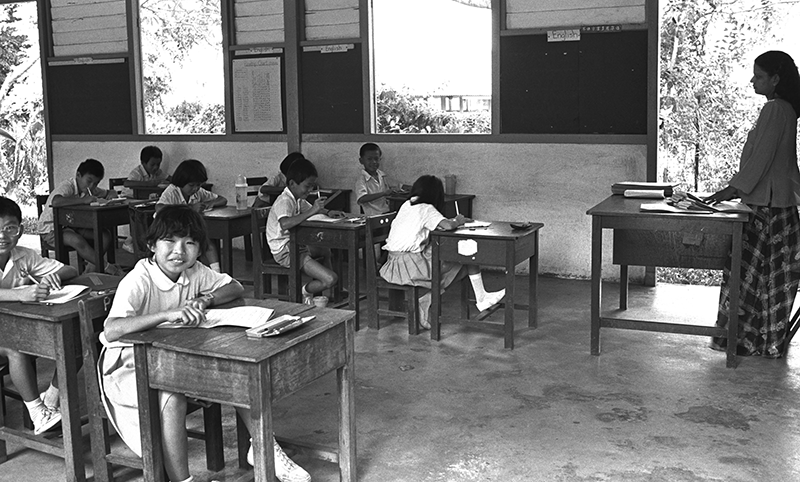

Seeing that Lim Chu Kang needed a proper school, Neo donated five acres of land and a sum of money to set up Kay Wah School (present-day Qihua Primary School) in 1938. Subsequently, Kay Wah School opened branches in Nam Hoe Village and the nearby Ama Keng Village (named after a temple dedicated to Mazu, goddess of the sea, which was built in the area in 1900).15

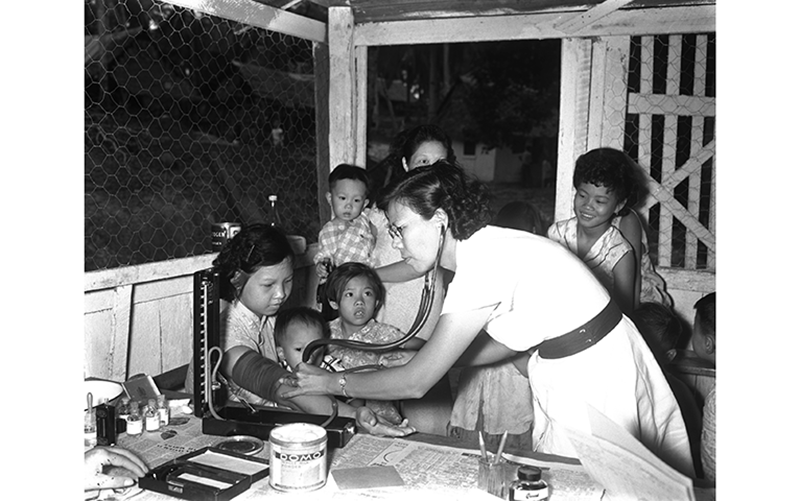

At Neo’s behest, the government eventually opened a maternal clinic, staffed by a matron trained in midwifery, in the village in 1940. As a result, Neo no longer had to drive in the dark of night to send a woman in labour to the nearest hospital, which was what he used to have to do.16

In 1937, the Nanyang Siang Pau newspaper described the Lim Chu Kang area as a well-equipped model village of 5,000 that had acquired a distinctive character and atmosphere under Neo’s astute direction and hard work.17 Neo’s philanthropy, tucked away in remote Lim Chu Kang, might have lacked prominence but its impact on the lives of the villagers, most of whom were farmers, was immense.

Lim Chu Kang’s agrarian character began to change in the 1930s. In 1934, the government acquired 54 acres in Lim Chu Kang for the Royal Air Force (RAF) to build RAF Tengah. By December 1935, the airbase - which occupied 130 acres and had “one of the longest runways of any aerodrome in the Empire” – was declared ready for load testing. On 2 November 1936, the aerodrome was declared open after four aircraft, led by Air Commodore S.W. Smith, Commander of the RAF Far East, landed at 10 am.18

The War Years

World War II brought immense tragedy to Neo, who was deeply involved in anti-Japanese resistance activities from 1937. A key figure in the fundraising efforts, Neo was also a staunch supporter of Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang (KMT; Chinese Nationalist Party), with its capital in Chongqing in Sichuan, China.

In 1940, Neo was appointed by Chiang to head the Singapore branch of the KMT Youth League of the Three Principles of the People (三民主义青年团).19 One of his missions was said to consist of setting up two clandestine wireless transmission stations in his coconut estates to provide intelligence to Chongqing.

On 13 February 1942, with the imminent fall of Singapore to the Japanese, Neo and one of his sons were evacuated to India and thereafter to China. The following day, tragedy befell Neo when his entire family of 35 left behind in Singapore was massacred by the Japanese.20

While in China, Neo enrolled in Chiang’s “anti-bandit army and was instrumental in persuading many of the lawless to lay down their arms”. Neo said he enjoyed a close friendship with Chiang. “When General Chiang died, I was invited to attend his funeral, but I sent my son as a representative,” he told the New Nation newspaper in 1975. “We were in the same unit of the Chinese Army before the Cultural Revolution and Chiang was my junior.”21

When the Japanese Occupation ended, Neo returned to Singapore and found out that his entire family had been killed. He rebuilt his life, remarried and settled down in Lim Chu Kang. However, the Malayan Emergency (1948–60) brought new problems and a price of $15,000 was reportedly put on his head. Neo was supposedly unperturbed by this and remarked that “[his] flesh is very expensive indeed”.

Neo had good reason to be confident because he commanded the Singapore Rural Board (Western Region) Volunteer Police – which the government equipped with both arms and uniforms – for the Lim Chu Kang area. Neo was given six pairs of handcuffs and 14 shotguns, although the shotguns were more for dealing with tigers than criminals.22

Crime was rare as Neo had his own methods of dealing with offenders. Repeat and serious offenders were turned over to the government and repatriated to China, according to a Straits Times report. Those caught gambling had to buy and distribute biscuits to every household with an apology, while caught stealing were made to wear a huge paper hat with the words “I am a thief” and made to parade from house to house.23

That said, Neo did not take his safety for granted as was demonstrated in March 1953 when a reporter and photographer from the Straits Times decided to visit Neo at Thong Hoe Village.

“We stopped our car by the roadside, and asked where the headman was. ‘He is waiting for you,’ said the man, pointing to a big house in the centre of the village. We were startled. We had arrived unannounced. We walked into the house, followed by three silent men and were challenged by a grey haired man, who stared at us with silent hostility,” wrote the reporter. “‘I am Neo Tiew, and I own this village. Who are you, and what do you want with me?’ he asked.”24

When the reporter reached into his pocket for his press card, Neo immediately grabbed the pistol that hung from his hip. Introductions made, Neo explained his caution. “Forgive me, but I have many enemies. I do not intend to get caught off guard by strangers. I am a wanted man.”25

Threats to his safety did not dilute Neo’s concern for the welfare of the villagers. He was called “The Big Boss” by residents, and was regarded with affection and admiration. Neo was someone they could turn to for help and advice.26 In November 1952, he donated a generator to provide Thong Hoe Village with basic electricity supply.27

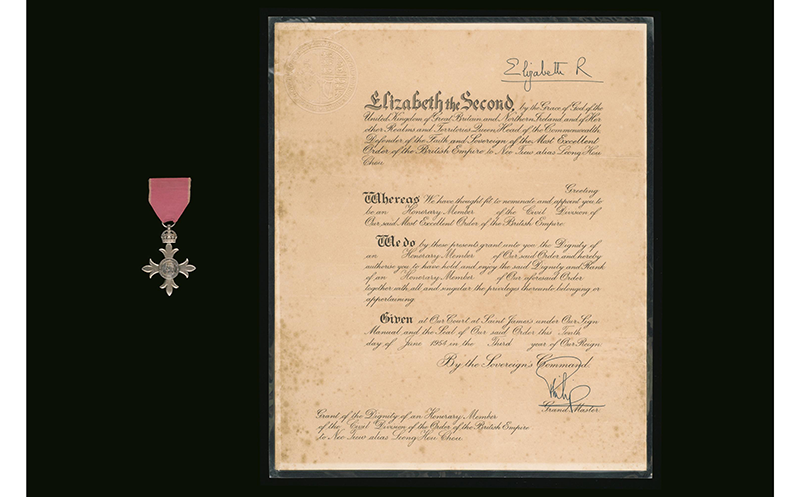

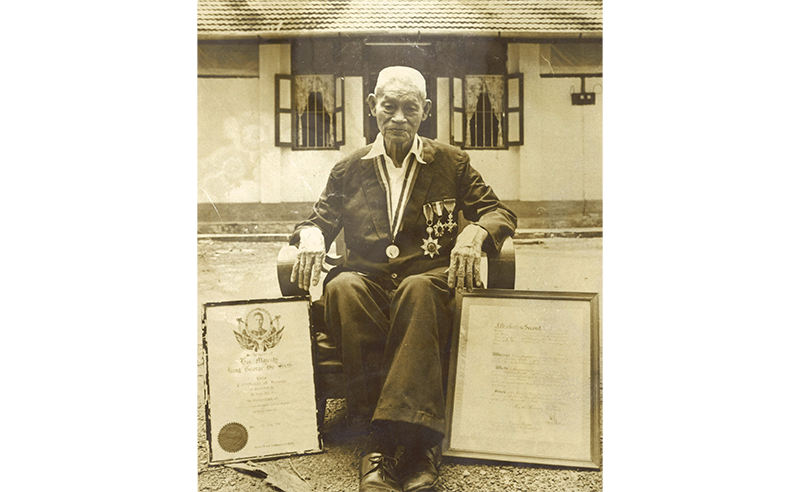

Neo’s work and contributions were recognised when he was admitted as a Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE) by Queen Elizabeth II in June 1954.28 Neo Tiew Road was also named in his honour.29

In the 1950s, the colonial government expanded its efforts in developing the island. From 1952, the government began acquiring land to resettle squatters and develop Singapore’s agricultural sector.30

Handicapped by a limited budget and high land costs, land acquisition did not take place on a large scale. Regardless, the government launched Operation Clean-up on 12 July 1956. With a budget of $5.5 million, more than 5,000 acres of old rubber plantations, swamp and scrubland in areas such as Lim Chu Kang, Kranji and Choa Chu Kang were cleared for resettlement. Within five years, 20 resettlement areas opened up and 2,000 people were relocated.31

Development and Resettlement

After Singapore attained self-government in 1959, the government began implementing infrastructure development programmes. In 1960, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew announced that a community centre – a modest, simple structure costing about $15,000 each – would be built at Thong Hoe Village, among other places.32

In May 1963, a new maternal and children’s health clinic was opened in Thong Hoe Village to some fanfare. Life further improved with the arrival of electricity. In March 1963, the Public Utilities Board announced its rural electrification programme at a cost of $1.4 million, covering 42 kampongs, rural roads and benefiting 2,000 homes.33

As farming villages across Singapore emptied out in the 1980s, this spelled the end of a unique way of life in Lim Chu Kang. Bennett Neo, Neo Tiew’s oldest grandson, grew up in Thong Hoe village in the 1970s. Bennett was born in in 1969 and lived in the village with his grandparents, uncles and their families. “We had a shop and I remember selling drinks and candy there,” he recalled. “We also operated a cinema with both open-air and sheltered seats.”

Bennett said that the family was quite self-sufficient as “we kept our own pigs and chickens and we also had fruit trees”. His grandfather may have been Neo Tiew the headman, but as they were living in rural Singapore, they had to use coconut husks as fuel for the kitchen stove.

As a child, Bennett enjoyed the carefree existence afforded by living in a rural area. He spent his time climbing trees and catching fish. His childhood friends included Malays and Indians, who could speak Hokkien. The highlight of the year for Bennett was the Hungry Ghost Festival. It was “most memorable as there would be an elaborate celebration with a getai show, an auction and a big dinner”.34

The area received a minor boost when the Housing and Development Board built Neo Tiew Estate at the junction of Lim Chu Kang Road and Neo Tiew Road in 1979. The estate provided neighbourhood amenities to people living around that part of Lim Chu Kang for about two decades until the estate was selected for the Selective En-bloc Redevelopment Scheme in 1998.35 In 2002, the estate was taken over by the Singapore Armed Forces and turned into an urban warfare training facility that simulated fighting in a built-up environment.

The area’s physical transformation was, however, far from complete. At the National Day Rally in 2013, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong unveiled plans to transform Paya Lebar with the relocation of Paya Lebar Air Base. This would free up 800 hectares of land for “new homes, new offices, new factories, new parks, new living environments, new communities” – in effect, a blank slate in a choice site in the heart of the island.36

While this was welcome news to many, the new policy had a knock-on effect on Lim Chu Kang. In 2017, it was announced that Lim Chu Kang Road would be realigned for the expansion of Tengah Air Base to accommodate the relocation of assets from Paya Lebar Air Base. Six farms had to be cleared and the Choa Chu Kang Chinese Cemetery was to be reduced by one-third of its current size.37

In a further twist of fate, the Covid-19 pandemic has given Lim Chu Kang a new lease of life. In March 2019, just months before the coronavirus first emerged, the government announced a “30 by 30” goal to produce 30 percent of Singapore’s food needs locally by 2030.38

The plan attained a new urgency after the pandemic was declared and supply chains became severely disrupted. For a country that imports 90 percent of its food, the “30 by 30” goal was now a strategic imperative.

In October 2020, the Singapore Food Agency announced that Lim Chu Kang would be transformed into a “high-tech agri-food cluster” to strengthen Singapore’s food security and create jobs for Singaporeans. The food cluster is expected to “produce more than three times its current food production when completed” and development works are slated to start in 2024.39 Far from fading into irrelevance in increasingly urbanised Singapore, rural Lim Chu Kang is now poised for a bright new future. It appears that Neo Tiew’s efforts over a century ago are still bearing fruit.

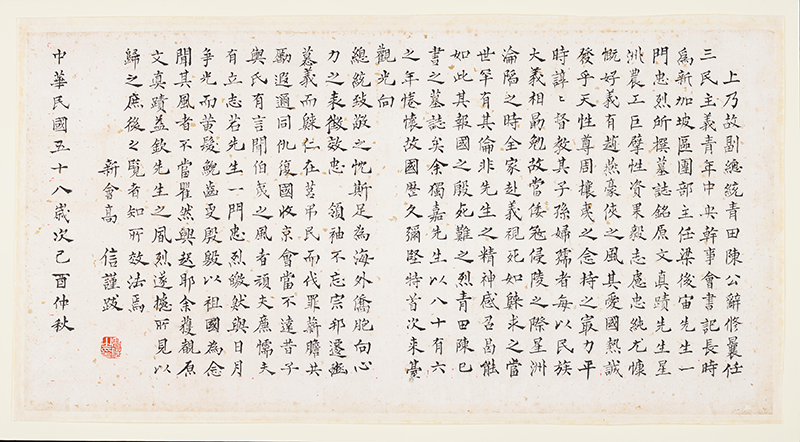

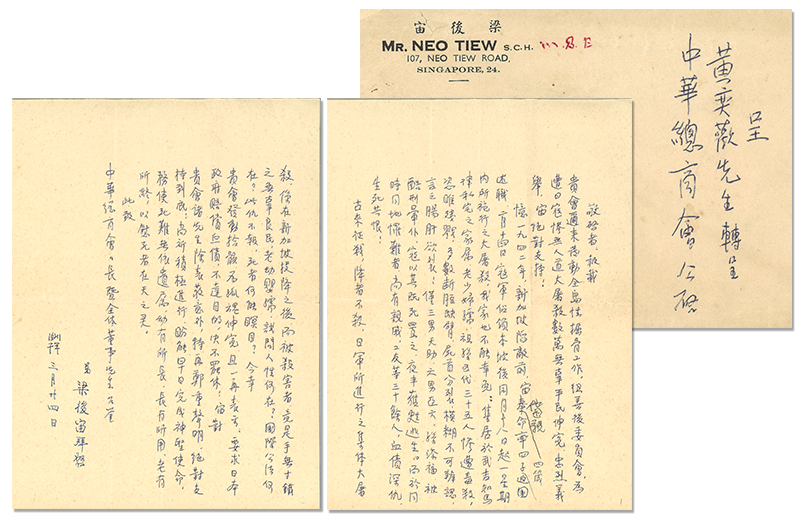

The National Library of Singapore’s Peng Lee Er Collection, Hsu Yun Tsiao Collection and Singapore Lam Ann Association Collection contain photographs and personal documents relating to Neo Tiew. These include photographs of the medals and certificates of honour awarded to Neo by the Chinese Kuomintang government and the British colonial government for his help defending Singapore during World War II and the Malayan Emergency as well as his contributions in developing Lim Chu Kang.

There are also photographs of the scenery and amenities in Lim Chu Kang such as Kay Wah School (now Qihua Primary School) and the Nam Hoe provision shop. Other photographs include those of Neo’s family and friends, his funeral in 1975 and the epitaph presented to him in 1946 by the Kuomintang government in memory of the massacre of 35 of his family members during the Japanese Occupation.

A letter written by Neo to the Chinese Chamber of Commerce during the exhumation of war victims in Singapore in 1962 describes the torture and killing of his family members.

Readers can make a request to view the following materials from the Reference Counter at Level 11 of the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library, National Library Building.

* 彭丽儿珍藏: 梁后宙生前照片、底片和治丧文件 (Call no. RCLOS 305.8951 PLE; Accession no. B29487728C)

* 新加坡宗乡会馆联合总会许云樵馆藏: 梁后宙生前照片 (Call no. RCLOS 305.8951 XJP-[HYT]; Accession no. B27705320D)

* 新加坡南安会馆珍藏: 新加坡中华总商会鸣冤委员会文件及其他信件 (Call no. RCLOS 959.5703 XJP; Accession no. B32427

Alvin Tan is an independent researcher and writer focusing on Singapore history, heritage and society. He is the author of Singapore: A Very Short History – From Temasek to Tomorrow (Talisman Publishing, 2nd edition, 2022) and the editor of Singapore at Random: Magic, Myths and Milestones (Talisman Publishing, 2021).

NOTES

-

Jean Lim, “Farmlands in Lim Chu Kang,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 2009. ↩

-

Also known as Neo Ao Tiew (梁后宙). ↩

-

Alexander W. Cashin was the son of Joseph William Cashin. At the time of his death, Joseph William Cashin was the managing director of the Opium and Liquor Farms of Singapore and had a “large financial interest” in them. He was also known to have made a fortune in land speculation “some years ago”, prior to his death. See “Death of Mr. J.W. Cashin,” Singapore Free Press, 8 August 1907, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Li Chengli 李成利, Lianghouzhou yu lin cuo gang 梁后宙与林厝港 [Neo Ao Tiew and Lim Chu Kang] (Singapore: Singapore Nan’an Association Arts and Culture Club, 2015), 41, 42. (From National Library Nan’an, Singapore, call no. Chinese RSING 305.8951 LCL) ↩

-

Fang Baicheng 方百成 and Du Nanfa 杜南发, eds., Shijie fujian mingren lu. Xinjiapo bian 世界福建名人录. 新加坡编 [Prominent Figures of the World Fujian Communities: Singapore] (Singapore: Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan, 2012), 265. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Chinese RSING 920.05957 PRO) ↩

-

Li, Lianghouzhou yu lin cuo gang, 43. ↩

-

Mirza Mohamed Ali Namazie was the founder of the firm M.A. Namazie and Sons. He was a Justice of the Peace and a member of the Singapore Municipal Commission for several years. He commissioned and financed the construction of Capitol Building. ↩

-

Neo also leased 60 acres from Cashin. See Han Sanyuan 韩山远, Wei yang lin cuo gang bendi chuanqi renwu lianghouzhou 威扬林厝港本地传奇人物梁后宙 [The legend who reigned over Lim Chu Kang – Neo Ao Tiew] in Singapore Lam Ann Association Committee 新加坡南安会馆委会, Xinjiapo nan’an xianxian zhuan 新加坡南安先贤传 [Stories of Lam Ann Pioneers in Singapore], vol. 1 (Singapore: Singapore Nan An Association, 1998), 141–43 (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Chinese R959.570099 XJP-[HIS]). The naming of the village after the provision shop was a common practice that E.H.G. Dobby documented in his 1940 survey piece. See E.H.G. Dobby, “Singapore: Town and Country,” Geographical Review 30, no. 1 (January 1940): 84–109. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Han, Wei yang lin cuo gang bendi chuanqi renwu lianghouzhou, 151. ↩

-

Han, Wei yang lin cuo gang bendi chuanqi renwu lianghouzhou, 151. ↩

-

“Page 7 Advertisements Column 2: Government Notification,” Malaya Tribune, 8 October 1930, 7. (From NewspaperSG). The tender notice was issued by Deputy Colonial Engineer R.I. Nunn. ↩

-

“The Rural Board’s Work,” Singapore Free Press, 10 April 1931, 12; “The Annual Report,” Singapore Free Press, 10 March 1932, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Han, Wei yang lin cuo gang bendi chuanqi renwu lianghouzhou, 151; Li, Lianghouzhou yu lin cuo gang, 84–87. The village was officially named Thong Hoe in 1949. See Ah Dan 啊丹, “You shanghao de ming de jiedao yu xiangcun” 由商号得名的街道与乡村 [Streets and villages named after the business], Lianhe Wanbao 联合晚报, 28 January 1984, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lim Chin Sei, oral history interview by Jesley Chua Chee Huan, 20 April 1987, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 3 of 9, 30:11, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000766-3). [Note: Interview is in Hokkien] ↩

-

Li, Lianghouzhou yu lin cuo gang, 90; “About Us,” Qihua Primary School, accessed 27 March 2022, https://qihuapri.moe.edu.sg/about-us/school-profile/school-profile/. Today, Kay Wah School is known as Qihua Primary School and is located at Woodlands Street 81. ↩

-

Li, Lianghouzhou yu lin cuo gang, 89. ↩

-

“Tan dao xing zhou mofan cun” 談到星洲模範村 [Speaking of Sin Chew Model Village], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 13 February 1937, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“How the Money Goes,” Malaya Tribune, 5 October 1931, 3; “As I Was Saying,” Singapore Free Press, 11 June 1934, 8; “New Service Aerodrome Ready,” Straits Times, 1 December 1935, 5; “Tengah Drome Under Test,” Singapore Free Press, 2 December 1935, 6; “Landing at New Aerodrome,” Malaya Tribune, 2 November 1936, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board, “KMT Certificate of Appointment Bestowed Upon Neo Tiew by the Overseas Chinese Affairs Commission,” 1951, Roots, https://www.roots.gov.sg/Collection-Landing/listing/1269454. ↩

-

Douglas Chan, “The Big Boss” New Nation, 23 November 1975, 5. (From NewspaperSG); Li, Lianghouzhou yu lin cuo gang, 96–97. Neo’s involvement and role in anti-Japanese activities such as the China Relief Fund is not documented in extant English-language scholarship. ↩

-

Chan, “The Big Boss”; Peter Ong, “A Grand Man Recalls His Past…,” New Nation, 22 April 1975, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Singapore Rural Board (Western Region) Volunteer Police, 1950s, photograph, National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board, https://www.roots.gov.sg/Collection-Landing/listing/1265464; Chan, “The Big Boss.” ↩

-

Low Mei Mei, “When Tigers Roamed Free and Thieves Got Paraded,” Straits Times, 9 December 1986, 18. (From NewspaperSG); Chan, “The Big Boss.” ↩

-

“Man with Hand of Iron Rules the Village of No Crime,” Straits Times, 8 March 1953, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chan, “The Big Boss.” ↩

-

“Lianghouzhou zi zhi fa dianji tong he cun da fang guangming wei dazhong fuwu sui kuishi yi buzu xi” 梁後宙自置發電機通和村大放光明為大眾服務雖虧蝕亦不足惜 [Liang Houzhou’s self-built generator, Tonghe Village, shines brightly to serve the public, even if it loses money, it is not a pity], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 25 November 1952, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Queen Makes Three Malayans Knights,” Straits Budget, 17 June 1954, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Detail Maps for 1954,” Singapore OneMap, accessed 8 October 2023, https://www.onemap.gov.sg/hm/. Neo Tiew Road appears as early as the 1954 edition. We can surmise that the road was named sometime in the early 1950s. ↩

-

“Government to Buy Land for Squatters,” Straits Times, 16 July 1952, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Square Deal for Squatter Farmers,” Straits Times, 12 July 1956, 9; “Govt. Opens Up New Resettlement Area for Farmers,” Singapore Free Press, 30 November 1961, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lee Kuan Yew, “The Opening of Minto Road Community Centre,” speech, Minto Road Community Centre, 9 January 1960, transcript, Ministry of Culture. (From National Archives of Singapore, document no. lky19600109) ↩

-

“Priority for Power in the Kampongs,” Straits Times, 23 March 1963, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Bennett Neo, email interview, 26 February 2022 and 13 March 2022. ↩

-

Nur Syahiidah Zainal, “Abandoned, But Memories Still Linger On,” Straits Times, 20 April 2015, 10–11. (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website); “RSAF Jets in First Road Runway Exercise,” Straits Times, 17 April 1986, 10. (From NewspaperSG). Two A-4 Skyhawks and two F-5E Tigers aircraft were involved in this exercise. ↩

-

Lee Hsien Loong, “Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s National Day Rally 2013 (English),” speech, Prime Minister’s Office Singapore, 18 August 2013, https://www.pmo.gov.sg/Newsroom/prime-minister-lee-hsien-loongs-national-day-rally-2013-english; Rachel Au-Yong, “Graves, Farms to Make Way For Larger Tengah Base,” Straits Times, 19 July 2017, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/graves-farms-to-make-way-for-larger-tengah-base. ↩

-

Au-Yong, “Graves, Farms to Make Way For Larger Tengah Base.” ↩

-

Chang Ai-Lien, “Singapore Sets 30% Goal for Home Grown Food by 2030,” Straits Times, 8 March 2019, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/spore-sets-30-goal-for-home-grown-food-by-2030. ↩

-

Cindy Co, “Lim Chu Kang to be Transformed into High-Tech Agri-Food Sector under SFA Master Plan,” Channel NewsAsia, 20 October 2020, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/lim-chu-kang-be-transformed-high-tech-agri-food-cluster-under-sfa-master-plan-730821. ↩