Terraces on Tagore: The Curious Origins of Teachers' Housing Estate

The Singapore Teachers’ Union wanted a clubhouse. It ended up building a housing estate.

By Sharon Teng

People living in private residential estates like Opera Estate and Sennett Estate end up developing a strong sense of camaraderie over time as neighbours became friends. In Teachers’ Housing Estate, the special bond among residents was established quickly because most of the original homeowners in the area shared a similar profession – they were, as the name of the estate implies, teachers.1

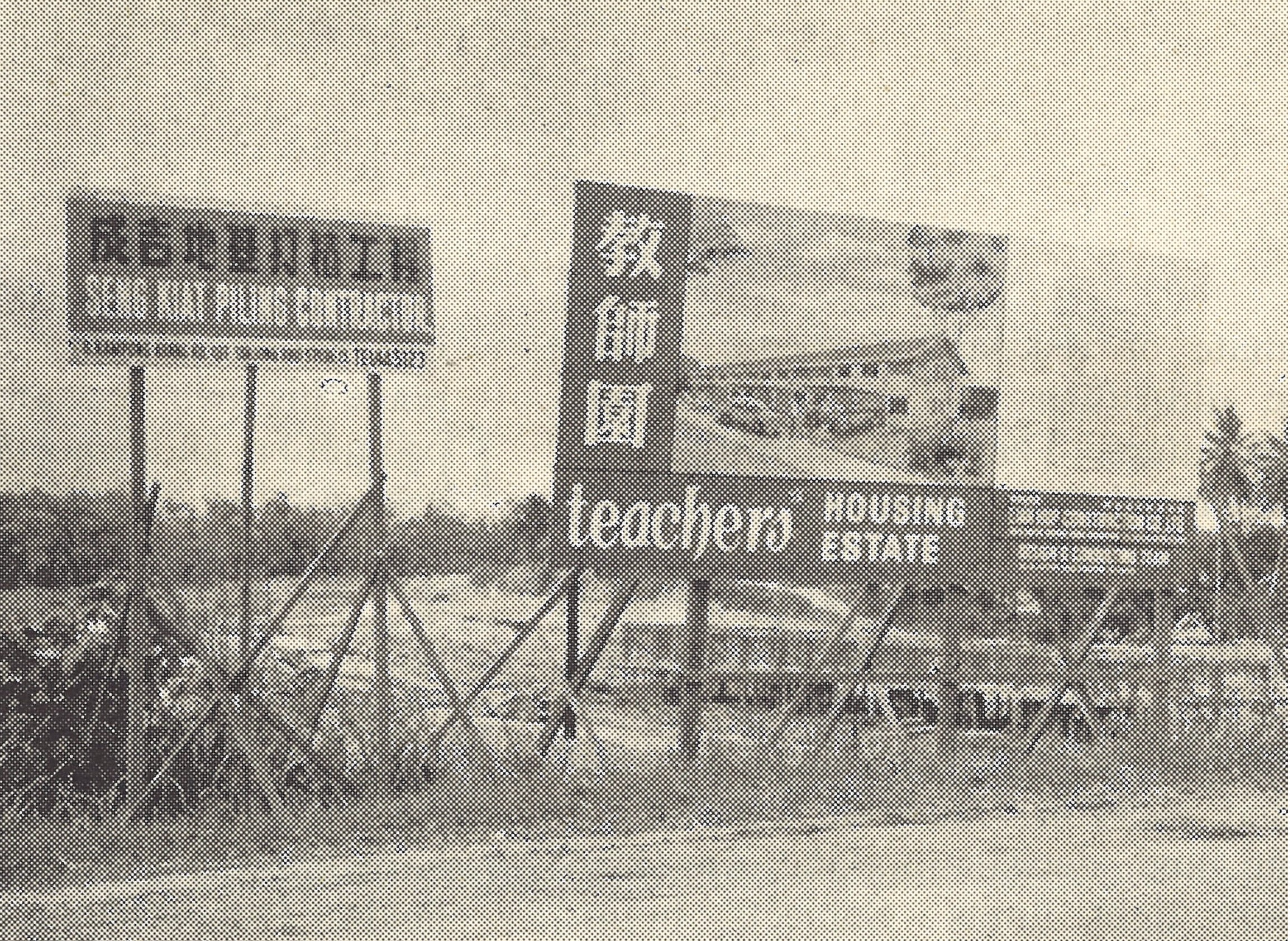

Located at the junction of Upper Thomson Road and Yio Chu Kang Road, Teachers’ Housing Estate came about thanks to the efforts of the Singapore Teachers’ Union (STU). The estate has a somewhat curious history: the primary reason for building it was because the union wanted to have a clubhouse for its members.

Work on the 20-acre site began in the late 1960s. When the estate was officially opened in 1971, about 70 percent of the 256 homes in the estate were owned by teachers. The clubhouse was built a few years later.

An Estate for Teachers

The STU mooted the idea of building a Teachers’ Estate with its own clubhouse in 1967.2 Yeoh Beng Cheow, a teacher at Bartley Secondary school and the union’s deputy general secretary in 1968, was involved in the conception and development of Teachers’ Housing Estate, along with then STU president Karim Bagoo.3

In a 1995 interview with the Straits Times, Yeoh said that the union had planned to build a clubhouse for several years but nothing was done, so he and his colleagues decided that the STU committee would do so. Unfortunately, there were problems. “The union could not afford to buy a centrally sited piece of land large enough for a clubhouse and for outdoor facilities,” according to the news report. The union considered a site further from the city which would be cheaper. However, being further away would not be convenient for members. “In the end, the committee came up with a novel plan: develop a housing estate around the clubhouse,” the paper reported.4

Yeoh recalled in his 2010 oral history interview: “At that time, we had no money for a clubhouse. There was a fund of about $80,000 set aside, too small for anything. With that, we could probably buy a house somewhere and turn it into a clubhouse. But in my view, that was unacceptable because the house would eventually degenerate into a mahjong house and that would tarnish the image of the profession. An idea struck me one day, that STU [Singapore Teachers’ Union] should develop a housing estate and acquire the land within the estate for a clubhouse.”5

The site that was eventually chosen was near Sembawang Hills Estate. It had been a gambier and pepper plantation in the mid-19th century before being converted into a pineapple plantation. It subsequently became a rubber plantation named Hup Choon Kek towards the end of the 19th century.6 Teachers’ Estate was also located near Serangoon Housing Estate and Windsor Park Co-operative Housing Estate where many teachers lived. It was anticipated that teachers living in these two estates as well as the new Teachers’ Housing Estate would become regular patrons of the clubhouse.7

In recollecting the initial planning of the estate and clubhouse, Yeoh envisioned that the “housing estate would be sited away from the city and with sufficient teachers living there, the clubhouse would be patronised and running expenses could be met”.8

In 1967, a committee for the housing project was formed, headed by Bagoo as committee chairman. Other committee members included Yeoh, who was appointed committee secretary, and Lawrence Sia, the general secretary of the STU.9

Then Minister for Finance Lim Kim San agreed to release $5 million for teachers who needed housing loans.10 As he explained at the opening of the estate on 19 October 1971 (by which time he was the education minister): “When Devan [Nair] first approached me regarding a Government loan to help members of the Teachers’ Union to build their own homes, I had no doubts about the benefit of such a scheme. We were then in the midst of encouraging our citizens to become home-owners through the Housing and Development Board home-ownership scheme, and the plan of the STU ties in beautifully with the overall plan to make Singapore a home-owning democracy.”11

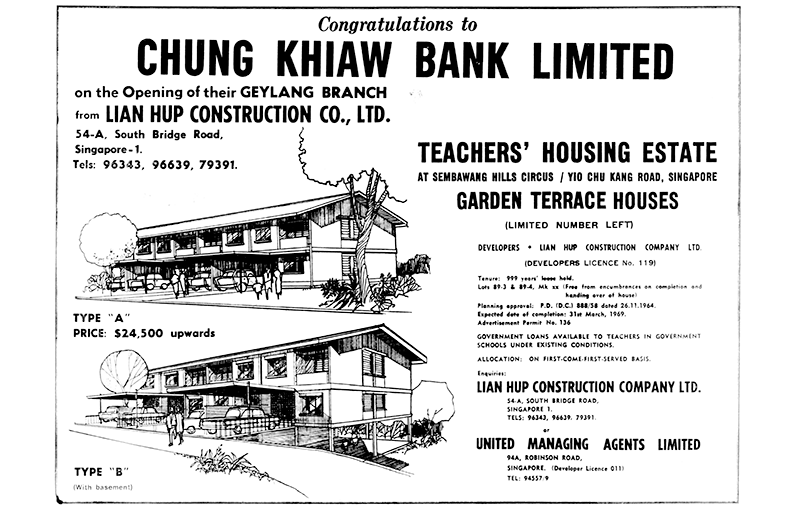

The STU appointed Lian Hup Construction Company as the developer. As Yeoh recalled in 1995: “I was in my early 30s then, full of fire and drive. Yes, we had no technical background. So we found a developer, and told him: You buy the land, build the houses. We will arrange for buyers and financing. I gave him quite tough terms: We pay you 10 per cent downpayment, 90 per cent on completion. This way, it was in his interest to complete the project fast.”12

Building Homes

Under the STU’s arrangement with Lian Hup, the developer agreed to give the union a piece of land of about 90,000 sq ft (8,361.3 sq m) for free which would be used for the clubhouse.13

For each house built by Lian Hup, the STU paid the developer $24,000. The union then sold the houses and used the difference to fund the building of the clubhouse. These were priced from $24,500 for an intermediate double-storey terrace house to $30,000 for a corner double-storey terrace unit with a basement.14 The STU offered housing loans that ranged from $13,800 to $24,000, with the repayment period between six and 12 years.15

However, the initial reaction by teachers was lukewarm. There were other options, prices of houses elsewhere were comparable, and many considered the estate to be too rural; the site had dirt tracks leading to it and was surrounded by farmland.16 Potential homebuyers also had reservations about whether the STU could complete the project, given that this was not something the union had done before. In addition, there were concerns about flooding in the estate as it was lower than Yio Chu Kang Road.17

Subsequently though, when bookings for the estate were offered to other government servants and the general public, there was a healthy response as the prices of the houses were considered reasonable.18

A Neighbourly Spirit

All 256 houses in Teachers’ Estate were completed by June 1969.19 The housing committee met up with the Advisory Committee on the Naming of Roads and Streets and suggested that the roads in the estate be named after poets or people well known in the education or literary fields. The proposal was accepted. Roads include Munshi Abdullah Avenue, Tagore Avenue and Tung Po Avenue.

In 1971, when the estate was officially opened, 180 of the homes were owned by teachers.20 Neighbourhood amenities were slowly added. By 1974, the estate had a grocery shop, a tailor’s shop, a hairdressing salon, a bakery, a small church, and a bus terminus with buses to town and Jurong. However, residents had to travel to Nee Soon and Thomson Road for the nearest wet markets.21

“Although the estate is a bit way out, I don’t mind,” said one resident in 1974. “It is really quite convenient. We have the fishmonger, the egg woman and the newspaper man making their rounds to the homes every morning.” She did wish that more hawkers would come by though.22

Crime was one of the problems faced by residents in the early days. A few months after moving in, residents reported two burglaries in October 1969: thieves had broken into houses via window grills. “At that time, the families that moved in were far and in-between,” recalled a pioneer resident. “The thieves found the homes a good target, even during the day, as most of us would be away working.” Alarmed, the residents formed a vigilante corps and the place acquired the nickname “Whistling Estate” because residents used police whistles to summon help from neighbours. Home burglaries eventually stopped when more people moved into the estate, police patrols increased in frequency and residents kept watch dogs.23

Given that the majority of the residents shared a similar occupation, a community spirit quickly developed. Besides home visits, they would go for outings together and many also joined the estate’s organised activities. Carpooling was the norm for travelling to work, and help was never far away if a resident’s car developed mechanical problems. “Teachers who find themselves teaching in schools in the same locality are quite ready to give lifts to each other,” said Mrs T. Broughton, a teacher and resident. She herself got a lift from her neighbour teaching in the same school.24

The same neighbourly spirit was also evident during school holidays, when spring-cleaning and house-painting were done en masse. “Whenever we feel that it is time the exteriors need a new coat of paint we just consult our neighbours in the same row, decide on the colour scheme and get on with the painting. Apart from cutting down on cost, we all agree it would give the houses a neater appearance,” said another resident.25

Social life in the estate revolved around the communal activities organised by the Teachers’ Housing Estate Residents’ Association. Excursions were organised to visit places of interest and, on occasion, welfare homes. Yoga classes for ladies were held in one another’s homes on a rotation basis, and youths attended twice-weekly sparring sessions at the basement of a resident taekwondo enthusiast. Residents were also treated to a monthly sale at the Teachers’ Centre’s mini-supermarket.26

In 1973, Tan Wee Kiat, the president of the Residents’ Association, noted that “[t]hough the Teachers’ Estate did not start out as a social experiment, it has nevertheless shown that a friendly, more co-operative community is forged when residents are of the same profession and socio-economic background”.27

Teachers’ Centre

With the estate built, the STU embarked on plans to build a clubhouse, which would also serve as the union’s headquarters.28 The original plans for the clubhouse were expansive: it included facilities such as a library, a kindergarten, a hostel, a restaurant, a swimming pool, tennis courts, a multipurpose hall and a field with a 400-metre running track. The clubhouse was projected to cost half a million dollars to build. However, in 1971, the STU only had $80,562 from its building fund and a further $160,000 from the estate developer as commission for the housing project.29

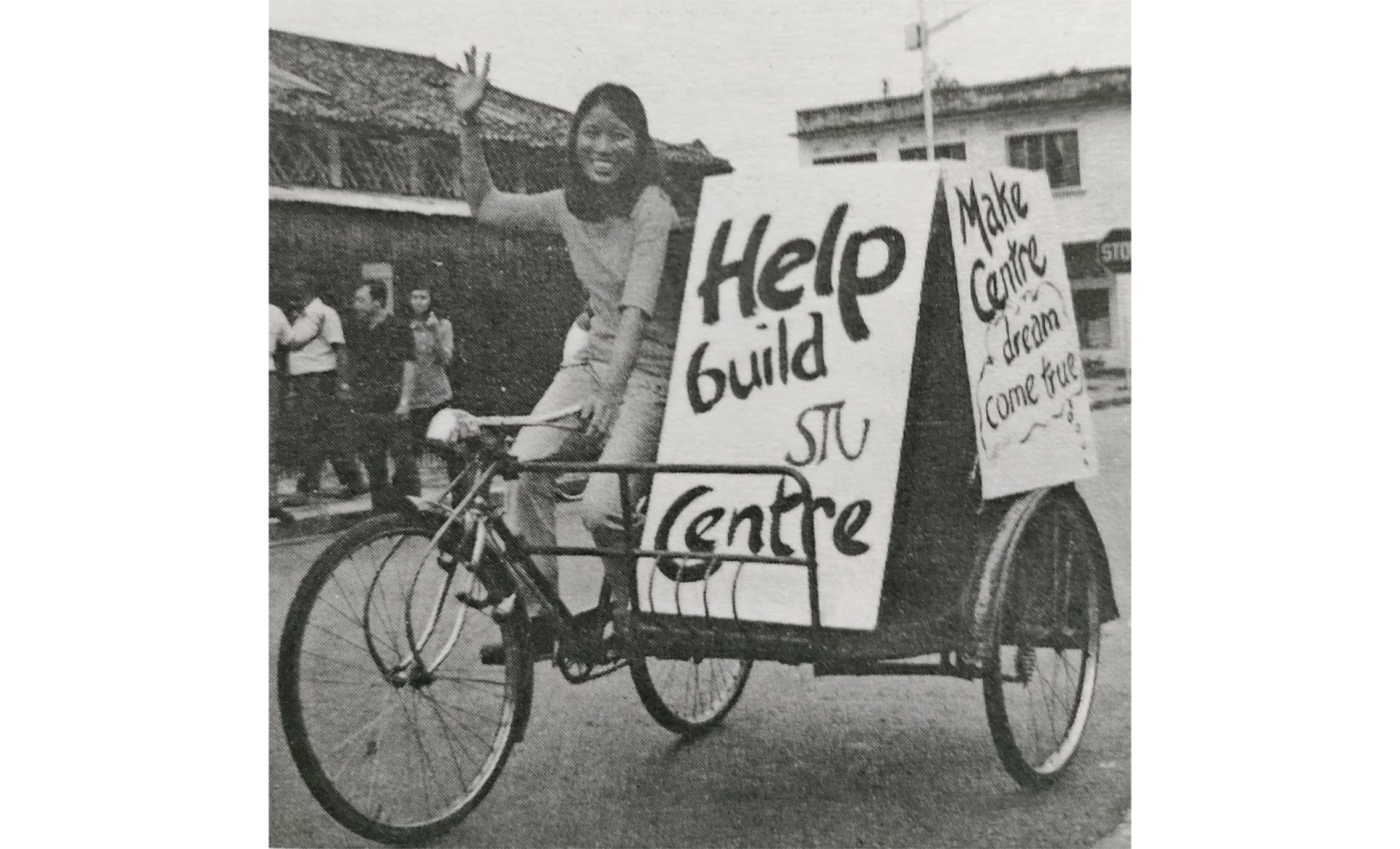

To raise money, the STU launched a series of fundraising activities from October 1972. The aim was to raise $150,000 (30 percent of the estimated cost for phase one) for the clubhouse, which would be called the Teachers’ Centre.30 One of the activities in February 1973 was a “trishawthon”, which raised $34,671.31 The STU also appealed to teachers to donate to the clubhouse fund and over 300 teachers pledged a total of $35,540. In 1973, the union received a $100,000 loan from the government.32

The Teachers’ Centre was finally completed in the second half of 1973, and on 19 October 1974, the STU held its anniversary celebrations at the centre for the very first time. However, not all facilities had been built. The swimming pool was completed in 1975, the tennis court in 1978, and two squash courts were only added 10 years later.33

In 2010, the STU leased out the land that the centre had occupied to a private developer and the union relocated to Serangoon Road that same year.34 In a 2009 piece in the STU’s Mentor publication, Leow Peng Kui, a trustee of the union, wrote that the decision to move was not taken lightly and was made “after much thought and consultation”. “The re-current [sic] cost of maintaining the present Union Centre in tip top condition is prohibitive,” he wrote. “Furthermore, the facilities are under-utilised.” He noted that while there were “a lot of sentiments” associated with the place as it had been there for several decades, change was necessary. “[I]f we do not move ahead because of sentiment, we may compound the problems we will face in future,” he added.35

The site where the centre used to be is now occupied by Poets Villas, a cluster housing development.36

Teachers’ Estate Today

Despite its success, Teacher’s Estate was the only housing effort by the STU, though not for want of trying. In 1984, the union announced plans to build a second Teachers’ Estate in Bukit Timah, but those plans fell through. The 912 teachers who had expressed interest in this project were left disappointed.37

Over time, as with other housing estates around Singapore, some of the original terrace houses have been torn down, with three- and four-storey houses erected in their place. Nonetheless, the estate still retains the charm of a quaint and rustic neighbourhood. As a writer for a property website noted: “Although I could see that many of the houses are old – they still boast the original architecture… [b]ut they do not look rundown and the estate feels both comfortable and well-loved.”38

One of the original residents of the estate, Abdul Qayyum, paid $26,500 for a 3,200 sq ft (297 sq m) corner terrace house in 1969. By 1995, it had appreciated to about $1.4 million but he firmly declared that he had no intention of selling. “Many of us know each other as neighbours, and as colleagues. I’m so used to this place, I don’t intend to move anywhere else,” he said.39 According to a property website, a 2,700 sq ft (250 sq m) four-bedroom house on Omar Khayyam Avenue is currently on the market for $4.2 million.40

In 2004, it was announced that Teachers’ Estate would be upgraded under the Estate Upgrading Programme; upgrading works began on 10 October 2004. The $1.16-million facelift included the creation of a new poetry gallery, a new staircase, new estate signage and refurbishment of parks.41 A new 7.6-hectare park planned for the estate is due to be completed by 2024.42

The housing committee met up with the Advisory Committee on the Naming of Roads and Streets and suggested that the roads in Teachers’ Estate be named after poets or people well-known in the education or literary fields.

* Munshi Abdullah Avenue/Walk – Named after Munshi Abdullah (1797–1854), the “Father of Modern Malay Literature”. He was a language teacher, interpreter and scribe who tutored Stamford Raffles in Malay.

* Omar Khayyam Avenue – Named after Omar Khayyam (1048–1131), a Persian poet, astronomer and mathematician. He is best known as the author of the Rubaiyat, a verse form consisting of four-line stanzas.

* Kalidasa Avenue – Named after Kalidasa, one of the greatest poets and playwrights in India who lived around the 5th century.

* Tagore Avenue – Named after Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941), a Bengali poet who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913 and was knighted in England in 1914.

* Iqbal Avenue – Named after the Indian poet and philosopher, Muhammad Iqbal (1877–1938), who was a staunch advocate for the creation of a separate Muslim state.

* Tu Fu Avenue – Named after Du Fu (712–770), one of the greatest poets and social critics in Chinese history.

* Li Po Avenue – Named after the renowned Chinese poet, Li Po (701–762) (also known as Li Bai), who lived during the Tang Dynasty.

* Tung Po Avenue – Named after Su Shi (1037–1101) (also known by his pseudonym Su Tung Po), a poet, essayist, artist and public official who lived during the Song Dynasty.

REFERENCES

Dunlop, Peter K.G. Street Names of Singapore. Singapore: Who's Who Pub., 2000. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 DUN)

Ng, Yew Peng. What's in the Name? How the Streets and Villages in Singapore Got Their Names. Singapore: World Scientific, 2018. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 915.9570014 NG)

Savage, Victor R., and Brenda S.A. Yeoh. Singapore Street Names: A Study of Toponymics. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2013. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 915.9570014 SAV)

Sharon Teng is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She is part of the Arts and General Reference team, and manages the Social Sciences and Humanities Collection.

Sharon Teng is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She is part of the Arts and General Reference team, and manages the Social Sciences and Humanities Collection.NOTES

-

Betty L. Khoo, “Friendly Estate… Shining Example of Neighbourliness,” New Nation, 28 August 1973, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Mentor vol. 5, no. 1 (1975) (Singapore: Singapore Teachers’ Union, 1971–), 8. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 331.881137 M) ↩

-

Yeoh Beng Cheow, “Report on the Teachers’ Housing Estate,” in Teachers’ Forum, no. 1 (April–May 1968) (Singapore: Singapore Teachers’ Union, 1968), 12. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 331.88113711 TF); Yeoh Beng Cheow, oral history interview by Jason Lim, 25 April 2010, MP3 audio, Reel/ Disc 7 of 14, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 003463); “Our Story,” Singapore Teachers’ Union, accessed 30 January 2023, https://stu.org.sg/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/STU_75_Corp-Video.mp4. ↩

-

Chua Mui Hoong, “The Story Behind Teachers’ Estate,” Straits Times, 22 September 1995, 34. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Yeoh Beng Cheow, oral history interview by Jason Lim, 25 April 2010, MP3 audio, Reel/ Disc 6 of 14, 18:00–20.02. National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 003463) ↩

-

Lim How Seng and Lim Guan Hock, eds. 林孝胜, 林源福 主编 , 义顺社区发展史 / The Development of Nee Soon Community (Xinjiapo 新加坡: Yishun qu ji ceng zu zhi, guo jia dang an guan, kou shu li shi guan 义顺区基层组织, 国家档案馆, 口述历史馆, 1987), 36, 198, 200, 202–203. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 DEV); A Pictorial History of Nee Soon Community (Singapore: The Grassroots Organisations of Nee Soon Constituency; National Archives; Oral History Department, 1987), 23. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 PIC) ↩

-

Mentor vol. 5, no. 1, 8; Singapore Teachers’ Union, The Challenge of Change: The Modernisation of the STU 1968–1988 (Singapore: STU, 1989), 62. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 331.881137 SIN) ↩

-

Yeoh, oral history interview, Reel/ Disc 6 of 14, 23:33–24.00. ↩

-

Yeoh, oral history interview, Reel/ Disc 6 of 14.; Yeoh Beng Cheow, “Report Never Gave One Man Credit for Development of Teachers’ Estate,” Straits Times, 2 October 1995, 44. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Yeoh, “Report on the Teachers’ Housing Estate”; Yeoh, oral history interview, Reel/Disc 6 of 14; M. Nirmala, “Going to School Was Like Going to Heaven,” Straits Times, 13 October 2000, 60. (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website); “$1m Teachers’ Clubhouse,” Straits Times, 4 October 1968, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Pang Gek Choo, “Indomitable Kim San: A Man of Integrity,” Straits Times, 29 November 1996, 56. (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website); “Union to Celebrate 25th Anniversary,” Straits Times, 28 September 1971, 2. (From NewspaperSG); Lim Kim San, “Speech by Mr. Lim Kim San, Minister for Education at the Opening of Teachers’ Park and Foundation Stone Laying Ceremony on 19 October 1971 at 7.00pm,” 12 ½ milestone Yio Chu Kang Road, 19 October 1971. Transcript. Ministry of Culture. (From National Archives of Singapore document no. PressR19711019a) ↩

-

Yeoh, “Report on the Teachers’ Housing Estate,” 14–15; Chua, “The Story Behind Teachers’ Estate.” ↩

-

Singapore Teachers’ Union, The Challenge of Change, 62. ↩

-

Yeoh, oral history interview, Reel/Disc 7 of 14; Yeoh, “Report on the Teachers’ Housing Estate,” 15; Yeoh, “Report Never Gave One Man Credit for Development of Teachers’ Estate”; “$1m Teachers’ Clubhouse.” ↩

-

Yeoh, oral history interview, Reel/Disc 7 of 14; Ying Cheok Ping, “Teachers’ Estate Built by Many, Not Just One Man,” Straits Times, 26 September 1995, 30. (From NewspaperSG); Yeoh, “Report on the Teachers’ Housing Estate,” 14. ↩

-

Khoo, “Friendly Estate… Shining Example of Neighbourliness”; Chua, “The Story Behind Teachers’ Estate.” ↩

-

Yeoh, oral history interview, Reel/Disc 6 of 14; Yeoh, “Report on the Teachers’ Housing Estate,” 12. ↩

-

Yeoh, oral history interview, Reel/Disc 6 of 14; Yeoh, “Report on the Teachers’ Housing Estate,” 12. ↩

-

Mentor vol. 2 no. 2 (May 1972) (Singapore: Singapore Teachers’ Union, 1971–), 10. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 331.881137 M) ↩

-

Lim, “Opening of Teachers’ Park and Foundation Stone Laying Ceremony”; “Union to Celebrate 25th Anniversary.” ↩

-

Florence Tan, “Peace Now Reigns at ‘Whistling Estate’,” New Nation, 28 December 1974, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Francis Rozario, “Thugs Move into Housing Estates in the Suburbs,” Straits Times, 26 October 1969, 11. (From NewspaperSG); Tan, “Peace Now Reigns at ‘Whistling Estate’.” ↩

-

Khoo, “Friendly Estate… Shining Example of Neighbourliness”; Tan, “Peace Now Reigns at ‘Whistling Estate’.” ↩

-

Khoo, “Friendly Estate… Shining Example of Neighbourliness”; Tan, “Peace Now Reigns at ‘Whistling Estate’.” ↩

-

Khoo, “Friendly Estate… Shining Example of Neighbourliness.” ↩

-

“Teachers Plan Big Multi-purpose Complex,” Straits Times, 22 October 1967, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Mentor vol. 5, no. 1, 8–9; Singapore Teachers’ Union, The Challenge of Change, 62. ↩

-

Mentor vol. 2, no. 4 (September 1972) (Singapore: Singapore Teachers’ Union, 1971–), 12. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 331.881137 M); Mentor vol. 5, no. 1, 2; “STU Drive for Funds,” New Nation, 20 December 1971, 2; “Drive to Raise $150,000 for Teachers’ Centre,” Straits Times, 26 September 1972, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Mentor vol. 2, no. 10 (March 1973) (Singapore: Singapore Teachers’ Union, 1971–), 1, 6–7. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 331.881137 M); Mentor vol. 5, no. 1, 8; Maureen Chua, “Teachers Brave the Rain for Fund-raising Trishawthon,” Straits Times, 26 February 1973, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Mentor vol. 5, no. 1, 2, 8; “$100,000 Loan for Teachers’ Union,” Straits Times, 19 March 1973, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Mentor vol. 4, no. 5 (December 1974) (Singapore: Singapore Teachers’ Union, 1971–), 1. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 331.881137 M); Singapore Teachers’ Union, The Challenge of Change, 63. ↩

-

Leow Peng Kui, “Looking Back and Ahead”, Mentor (April-June 2009) (Singapore: Singapore Teachers’ Union, 1971–), 17. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 331.881137 M) ↩

-

Mentor vol. 5, no. 1, 13; “Teachers Housing Estate”, Singapore Land Authority – Integrated Land Information Service, accessed 3 February 2023, https://app1.sla.gov.sg/inlis/#/. ↩

-

“Longer Wait for a Teachers’ Housing Estate,” Singapore Monitor, 6 March 1984, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

TJ, “Touring Teacher’s Housing Estate: The Cheapest and Most Spacious Freehold Landed Estate (D26),” Stackedhomes, 26 December 2021, https://stackedhomes.com/editorial/touring-teachers-housing-estate/#gs.7mbvhw; Tan, “Peace Now Reigns at ‘Whistling Estate’.” ↩

-

Chua, “The Story Behind Teachers’ Estate.” ↩

-

“Teachers’ Housing Estate,” PropertyGuru, accessed 6 February 2023, https://www.propertyguru.com.sg/listing/24320544/for-sale-teacher-s-housing-estate. ↩

-

“Facelift for Teacher’s Estate,” Today, 16 October 2004, 8; “EUP Set for Sunday,” Today, 9 October 2004, 33. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ng Keng Gene, “$315m to Expand and Enhance Parks, Park Connector Network and Recreational Route,” Straits Times, 4 March 2021. (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website); “NParks to Develop Singapore’s Longest Cross-island Trail and 3 New Recreational Routes,” Channel NewsAsia, 4 March 2021. (From Factiva via NLB’s eResources website) ↩