Women and the Typewriter in Singapore's Herstories

The humble typewriter helped women become better educated, enter the workforce and contribute to society.

By Liew Kai Khiun

Mechanical to electric, manual to automated, ubiquitous to ornamental. Since it first entered commercial production in the 1870s, what is now seen as the humble typewriter has played a significant role in the history of the 20th century. Less well known is the fact that the typewriter was also a key force in shaping herstory in the same period. Women’s progress through the formal economy has been closely intertwined with the typewriter. Women typists, stenographers and secretaries bore witness to the technological, socio-economic and political changes from the 1900s to the tumultuous 1950s, and later the “electrifying” 1970s.

Women Typists in Prewar Singapore

In colonial Malaya, advertisements for typewriters began appearing in English-language broadsheets from the late 1890s.1 In the early days, companies in Malaya did not seem to hire many female typists. A letter to the Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser in 1908 notes that the “lady shorthand typist is a rare personage within the walls of commercial houses”, reflecting the general absence of women in this emerging trade.2

Female literacy rate was low in Singapore in the prewar period and women’s employment was largely confined to the informal sector.3 However, as attitudes toward women’s education changed, interest in secretarial skills like shorthand and typing became heightened. As M.R. Menon, the principal of the Young Men’s Christian Association’s (YMCA) School of Commerce, noted: “With the social advancement of womanhood, the Chinese girl labours under no false modesty. She is no longer content to sweep the floor and open the windows of the house and to do the cooking. Education has fired her with an ambition to do something.”4 The typewriter was to be part of the education and progress of women.

Shorthand and typing courses continued even during the period of the Japanese Occupation of Singapore (1942–45). Among the propaganda showcases were initiatives encouraging the progress of women through typewriting courses. Accounts in the English-language Syonan Shimbun (the newspaper that replaced the Straits Times during the occupation years) featured local Malay women undertaking typing courses as well as the introduction of the Kanji typewriter (which uses traditional Chinese characters).5

The Tumultuous 50s

Demand for typewriters grew significantly after the war. The trend started from the disruption of women’s education during the occupation years when many found themselves either too old or economically disadvantaged to continue with their education. Instead, these women attended commercial classes like typewriting and shorthand.6 Jobs that required such skills saw acute demand with the reestablishment of the civil service after the war.7

Just the ability to type alone was not always valued by employers though. In April 1953, there was a salary dispute played out in the Industrial Arbitration Court between the Singapore Government Administrative and Clerical Services Union and the Singapore Post and Telegraph Workers’ Union (SPTWU), and the Telecommunications Department. One of the key points of contention was the call for women teleprinter operators to receive the same salary as women postal clerks.8

Teleprinters were introduced in 1932 in the postal offices of Malaya – a milestone in communication technology.9 Also known as “typewriting by wire”, teleprinting entailed telegraphic instruments receiving printed messages via telephone cables and radio relay systems. The Posts and Telegraphs Department had affered teleprinter work to women typists “as an experiment” and “‘a different kind of job’ for the fair sex”.10

When pressed to increase the salary scale of teleprinters to that of clerks, the Telecommunications Department attempted to devalue the responsibilities of its 35 women teleprinter operators by claiming that they had engaged in frivolous tele-conversations with male pilots. When cross-examined by the union’s legal representative Lee Kuan Yew, the assistant controller of the Telecommunications Department, J. Metcalfe-Moore, said that his female workers had voluntarily taken on duties on long-range radio communication. He added: “The girls like talking to the pilots and the pilots like talking to them.”11 The court eventually ruled in favour of the teleprinter typists, and reduced the time to attain the maximum salary from 21 years to 17.12

Prejudice against teleprinter typists continued. Three years after the court ruling, a Straits Times cartoon characterised the teleprinter typist as having a “life of ease” and undeserving of her salary. The cartoon drew a sharp rebuke from Betty De Silva of the SPTWU. In her letter to the newspaper titled “The Tougher Sex”, she noted that teleprinter typists in the Telecommunications Department worked longer shifts and longer hours (42 hours per week) compared to typists in other government departments (36.5 hours per week). In addition, they were also called upon to perform other duties such as sending or receiving telegrams by telephone, gathering and compiling traffic statistics, operating telephone switchboards, communicating with aircraft on radio telephones and carrying out other clerical duties.13

De Silva wrote: “As for soft supervisors and ‘Crying Allowance’, it might enlighten your artist to learn that some supervisors have earned the reputation as strict disciplinarians, the respectful title of ‘the tiger’, the ‘hawk,’ etc.”. Below the published letter was the editor’s remark, seemingly contrite: “The joke, apparently, is on us.”14

More than a week before De Silva’s letter was published on 29 August 1956, the Singapore Standard had reported on 18 August that 53 staff from the Union Insurance Company of Canton had threatened a walkout after the company sacked one of its stenographers, Doris Phua, allegedly for “unsatisfactory” work.15 Phua was subsequently reinstated to her position, with an additional three months’ salary as compensation.16

Industrial strikes and labour disputes were part of Singapore’s politically tumultuous landscape in the 1950s. While their numbers were small, women typists played a part during the period of decolonisation and self-determination.

The Electrifying 1970s

When Singapore gained internal self-government in 1959 under the People’s Action Party (PAP), the typewriter was still out of reach for much of Singapore’s populace. However, by the 1970s, typewriters were in great demand in offices.17 By the mid-1970s, Singapore was importing around 70,000 typewriters per year, with many growing increasingly sophisticated with memory chips and computer functions.18

With the extensive provision of education opportunities to the general populace by the new PAP government, a more educated women workforce emerged.19 Collectively, these women provided additional labour to the government’s industrialisation drive to power the burgeoning local economy in the 1970s.20

Between 1970 and 1980, a radical spike was recorded in the women workforce: from 761,356, or 24.6 percent of a total of 1.9 million workers to 981,235, or 39.3 percent. In the fastest-growing industries of manufacturing, finance, business and trade, women – mostly single – registered a growth of over 120 percent within the same decade, exceeding the number of men.21

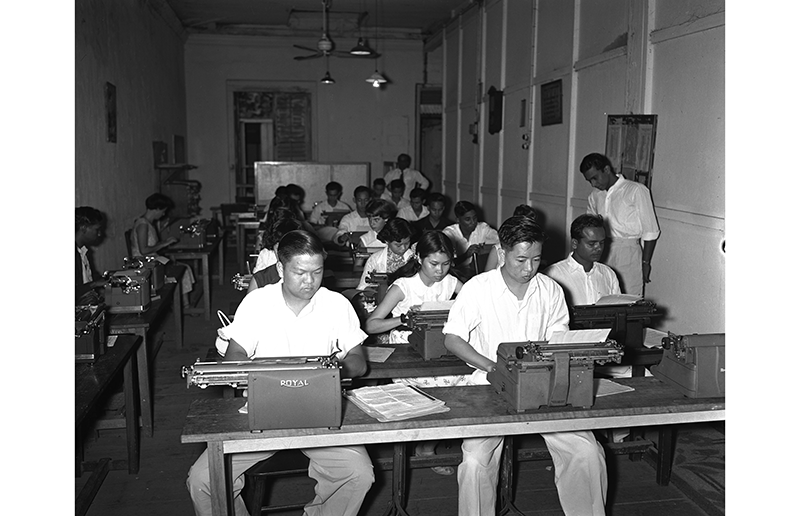

These changes were also reflected in the shifting demographics in women’s educational levels and participation in the labour force.22 The 1970 population census registered 56,939 men versus 26,002 women in the clerical sector. A decade later, the numbers reversed, with 65,931 men to 101,524 women, with the latter seeing a quadruple jump.23 Many women entered the workforce as typists and secretaries, becoming the first to handle increasingly sophisticated typewriters in new business environments.

“We Are Women, Not IBM Machines”

By 1978, Singapore had an estimated 14,800 employees under the category of “office support service”. Secretaries became highly sought after. Compared to the monthly salary of $323 and $560 for typists and stenographers respectively, secretaries commanded a higher monthly salary of almost $1,500.24

Embodying this desire to use a typewriter as a springboard was 22-year-old Nancy Khoo, a private secretary at a foreign bank, who was featured in the Straits Times in August 1970. After leaving school, Khoo worked in a food and beverage company as a telephonist-cum-receptionist. Attracted by what she perceived as the growing prestige of secretaries, Khoo enrolled in evening shorthand and typing courses and became a qualified secretary.

She told the Straits Times: “I was then earning $200 a month, now I’m getting more than $600. I also get an annual bonus. In four years’ time I will have a chance to travel on company expense, because after six years’ service we are supposed to pay head office in Manila a visit. I will like to do a managerial job next.” Her aspirations reflected a more promising career prospect that the typewriter had facilitated.25

However, such prospects were also premised upon the recognition of the contributions of the mainly female secretaries. As another secretary told the Straits Times in August 1970: “[W]e are women, and not IBM machines. Once in a while when we have done a job well we’d like to receive a compliment. We want to feel we are contributing towards the company. We want to take on some responsibility, to get involved and to use our initiative.”26

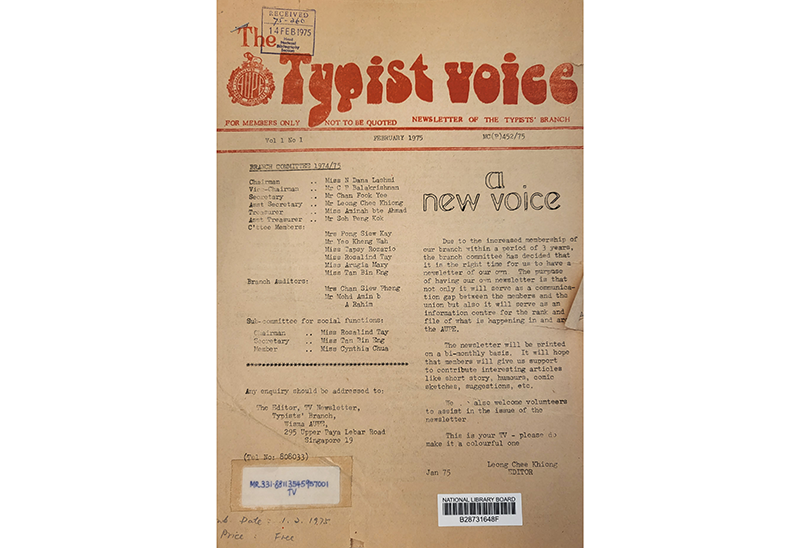

The growing visibility of the typewriting profession was reflected in the formation of two female-centric associations in the early 1970s. They were the Typists’ Branch from the main trade union, the Amalgamated Union of Public Employees, and the Singapore Association of Personal and Executive Secretaries (SAPES).27 These organisations aimed to provide more active support and representation of secretaries in Singapore.

What we know of the Typists’ Branch comes mainly from its short-lived newsletter, The Typist Voice, produced in 1975 to circulate information to its increasing membership, who were mainly women as reflected in their dominance in the branch committee.28

SAPES, on the other hand, began to find resonance with a new generation of female secretaries and executives. Starting with around 50 members and with the support of the Stamford Group of Colleges that provided typewriting courses, SAPES’s prominence in the 1970s came with the hosting of the Asian Congress of Secretaries in 1978.29 By then, the association’s membership had increased to 400 comprising mainly women.30 According to the assistant secretary of the organisation, Chua Lee Hua, “they were clearly tired of the stock image of secretaries as nothing more than wooly-headed dolly birds who sit on bosses laps and make coffee”.31

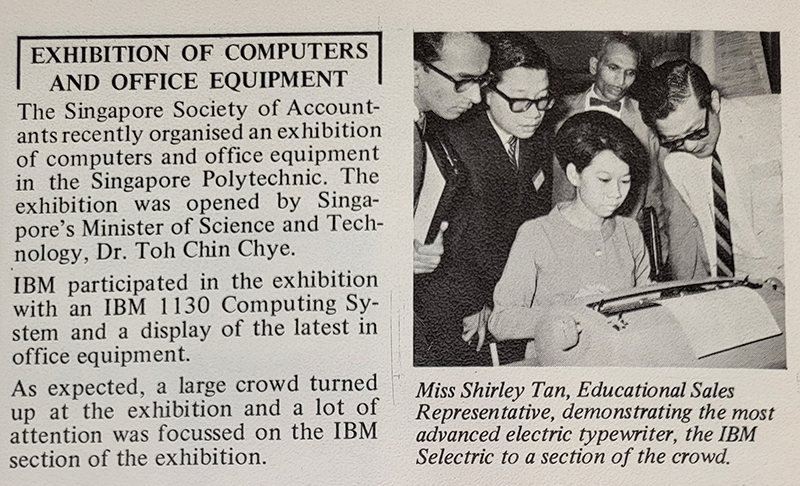

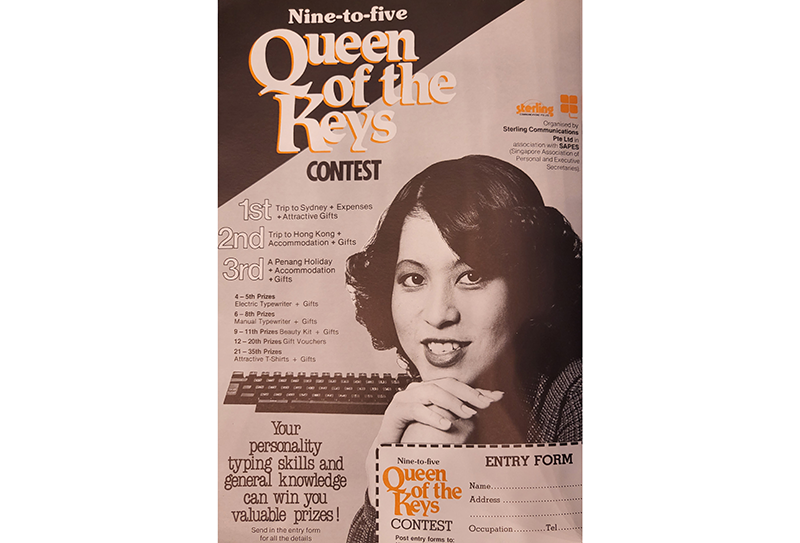

Following its inception in 1971, SAPES started organising annual public contests in search of the “ideal secretary”. These included the “Ideal Secretary Quest” in 1974 and “Queen of the Keys” in 1981.32 Qualities such as “good human and public relations attitudes”, having good “secretarial skills” and a “charming personality” were extolled.33 The association also celebrated International Secretary Week, organising international conferences and participating in trade exhibitions of office equipment.34 Its public inputs and endorsement became important to distributors of office equipment in the competitive industry.

The typewriter entered its twilight years in the 1980s as the era of microcomputers dawned.35 Over time, everyone who worked in an office was given a personal computer for their use. The job of stenographer and typist vanished, and typing pools dried up. And with everyone sending out their own emails these days, secretaries no longer take memos and type out letters. Instead, they have evolved to become personal assistants.

Typewriters and electronic word processors can no longer be found in offices. But even if their absence is little mourned today, they deserve to be remembered for their role in providing women with avenues for entering the workforce and, in the process, helping to write, or rather type out, herstory.

Dr Liew Kai Khiun has been researching Singapore’s history for the past two decades. He is currently an assistant professor with the School of Arts and Social Sciences at the Hong Kong Metropolitan University, and a former Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow (2021–2022).

Dr Liew Kai Khiun has been researching Singapore’s history for the past two decades. He is currently an assistant professor with the School of Arts and Social Sciences at the Hong Kong Metropolitan University, and a former Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow (2021–2022).NOTES

-

In an advertisement for the Remington typewriter by A.R Carbbe, the sole importer for the Straits Settlements, the device is described as “an investment that will pay. Saves time, money and labour. The use of the machine can be learned in 30 minutes… Writes four times as quick as the pen”. See “Page 2 Advertisements Column 4,” Daily Advertiser, 7 December 1891, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Shorthand for Girls,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 16 April 1908, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Sharon Lee, “Female Immigrants and Labour in Colonial Malaya: 1860–1947,” International Migration Review 23, no. 2 (June 1989): 309–31. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

According to M.R. Menon, since the YMCA School of Commerce opened in 1928, out of around 400 students enrolled, 60 were women and all of them ethnic Chinese. See “More Chinese Girls Work in Singapore Offices,” Straits Budget, 27 July 1939, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

‘’Katakana and Kanzi Typewriters Will Soon Be Fashion Here,” Syonan Shimbun, 24 July 1942, 4; “Of Interest to Women,” Syonan Shimbun Fortnightly, 5 June 1945, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“‘Commercials’ Are Big Draw for Better Jobs,” Singapore Free Press, 6 March 1957, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“War Over Clerks,” Singapore Free Press, 10 December 1946, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Problem Number One for Mr. Yong Is All About Women: Postal Pay Arbitration Opens,” Straits Times, 10 April 1953, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“A Demonstration of Teleprinters,” Malayan Tribune, 24 May 1933, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Typing Letters Across Malaya at 60 Words a Minute,” Straits Times, 19 March 1933, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Mr Yong Gives Clerks $500: Arbitration Award,” Straits Budget, 16 April 1953, 15. (From NewspaperSG). In a subsequent Industrial Arbitration Court ruling in 1965, the salary scale for teleprinter typists was increased from $137.50–$332.50 to $145–347.50, while the salary of teleprinter supervisors was raised from $400 to $425. See “Clerks Get a $15 Rise: Arbitration Award,” Straits Times, 17 October 1965. 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Tougher Sex,” Straits Times, 29 August 1956, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Tougher Sex.” ↩

-

“53 May Go on Strike Because Pretty Doris Is Under Notice,” Singapore Standard, 18 August 1956, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Doris (The Girl Who Nearly Caused a Strike) Gets ‘Windfall’,” Singapore Standard, 6 September 1956, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Local Companies Join the Technological Era,” New Nation, 31 August 1971, 10. (From NewspaperSG). Reflecting the transformation of offices in the 1970s, the sale of office equipment in the first quarter of 1970 was $5,874,632 compared to $16,189,261 for the whole of 1968. See Anthony Ramasamy, “Clearing the Desks for Action,” Singapore Trade and Industry, March 1971 (Singapore: Straits Times Press, 1961–1976), 8. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 381.095957 SIN) ↩

-

“Latest Machines to Help Firms to Increase Output and Efficiency,” Straits Times, 24 August 1975, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Linda Lim and Pang Eng Fong, Trade, Employment and Industrialisation in Singapore (Geneva: International Labour Organisation, 1986), 59–61. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 330.95957 LIM) ↩

-

Dick Wilson, “Singapore Is Poised for a Major Economic Breakthrough,” Singapore Trade and Industry, February 1970 (Singapore: Straits Times Press, 1961–1976), 33. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 381.095957 SIN) ↩

-

Khoo Chian Kim, Census of Population 1980: Release No. 4. Economic Characteristics (Singapore: Department of Statistics, 1981), 2, 12. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 312.095957 CEN) ↩

-

Janice Loo, “A Quiet Revolution: Women and Work in Industrialising Singapore,” Biblioasia 10, no. 2 (July–September 2014): 28–33. ↩

-

Khoo, Census of Population, 1980, 14–15. ↩

-

“Bouquet for the Personal Secretary,” Business Times, 6 March 1978, 14. (From NewspaperSG). Evidence of the growing recognition of the secretarial profession was already evident in the early 1970s, with pay grades based on academic qualifications, certification and experience. This ranged from $350 for those with just a Senior Cambridge Certificate and no prior working experience, to $1,400 for secretaries with university degrees working in multinational corporations. Judith Wong, “The Girls the Bosses Must Pamper,” Straits Times, 2 August 1970, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Wong, “The Girls the Bosses Must Pamper.” ↩

-

Wong, “The Girls the Bosses Must Pamper.” ↩

-

“No Longer on Their Own…”, New Nation, 20 March 1972, 3 (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The Typist Voice 1, no. 1 (Singapore: Typists’ Branch, Amalgamated Union of Public Employees, 1975–). (From PublicationSG). Other than several volumes found in the collection of the National Library Board, there remains scant information about the Typists’ Branch. Since the 1950s, typists in the public sector were placed in Division IV, alongside office boys and drivers with limited prospects. See “Division 4 Officers”, New Nation, 27 May 1974, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Upgrading Skills to Meet Challenges of the ‘Eighties,” Straits Times, 6 March 1978, 12. (From NewspaperSG). For details of the event, see Singapore Association of Personal and Executive Secretaries, Welcome to Third Asian Congress of Secretaries, Hyatt Singapore Hotel, 5–11 March 1978 (Singapore: The Association, 1978). (From PublicationSG). SAPES was renamed the Singapore Association of Administrative Professionals (SAAP) in 2005. It still exists today. See “About SAAP,” Singapore Association of Administrative Professionals, accessed 9 July 2022, https://saap.org.sg/index.php/about-us/history-logo-vision-mission. ↩

-

“About SAAP.” ↩

-

“Just Fed Up,” New Nation, 14 January 1975, 10–11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The Nine to Five Secretary, May 1981 (Singapore: Sterling Communications, 1981–), 52. (From PublicationSG) ↩

-

“Out to Prove Who Is the Best,” New Nation, 8 February 1974, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

In conjunction with the Asian Congress of Secretaries in 1978, SAPES also organised an exhibition of the latest office equipment at the Hyatt Hotel showcasing new products like the IBM Copier III, the IBM selectric typewriter 82C, IBM microsystems, videotype CRT screens from Videotron Singapore, Rank Xerox machines and telephone apparatus from Northeastern Telecom (Asia). See “Latest Office Equipment on Display,” Straits Times, 6 March 1978, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ilene Aleshire, “Computers Start to Put the Bite on Companies,” Straits Times, 27 May 1984, 19. (From NewspaperSG) ↩