Collection Focus: A Comic Book Version of Operation Jaywick

The story of Operation Jaywick, a daring attack on Japanese ships at Keppel Harbour in September 1943, is retold in a comic aimed at boys published in London in 1965.

By Gautam Hazarika

“At 5.15 a.m. on the morning of September 27, 1943 a terrific explosion shook the harbour of Singapore and a big Japanese tanker went up in flames. She was the first of seven ships to blow up at their moorings – victims of Operation Jaywick, a daring sabotage expedition in World War Two carried out by men of Unit Z of the Australian Experimental Station.”

This is the dramatic introduction to “The Cruise of the Krait” which retells, in comic book form, the story of the real-life Operation Jaywick, a clandestine attack by British and Australian commandos and sailors on Japanese ships in Singapore’s Keppel Harbour.

The story, which spans 12 pages, is one of 14 stories in The Victor Book for Boys: The Commandos at Singapore.1 Published in London in 1965 by D.C. Thomson & Co., Ltd., and John Leng & Co. Ltd., the hardcover book measures 19.3 cm by 27.6 cm. (The book is 124 pages long, though because the publishers counts the cover as page 1, the page numbers run to 128).

Operation Jaywick

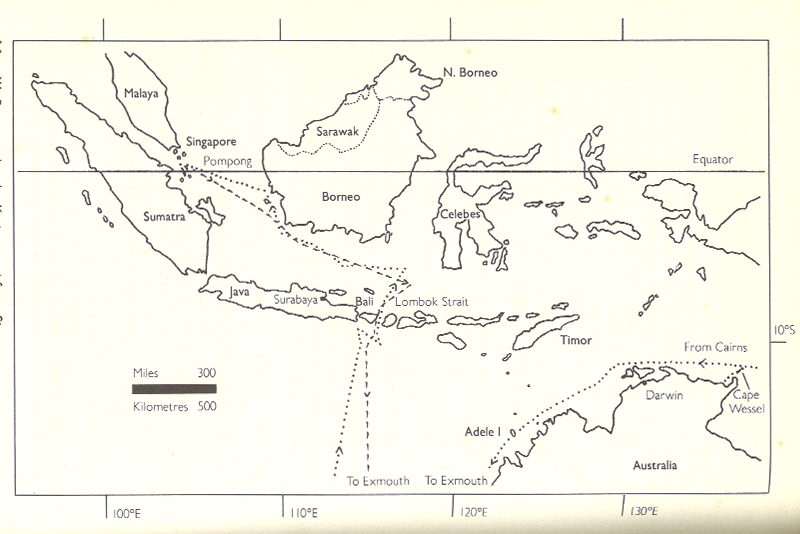

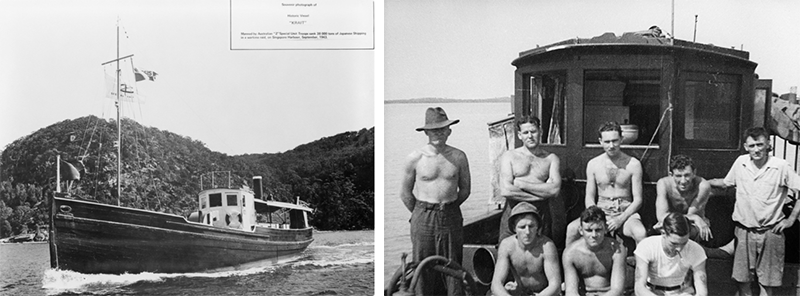

Operation Jaywick took place in September 1943. The team of 14 commandos and sailors, led by Major (later Lieutenant-Colonel) Ivan Lyon, sailed from Australia to Singapore in a fishing boat (the Krait), with the aim of sabotaging ships in Japanese-occupied Singapore.

They departed from Exmouth Gulf in Western Australia on 2 September 1943 and reached the waters near Singapore a few weeks later. On the night of 26 September, the commandos successfully paddled in small canoes into the Singapore harbour and attached explosives to Japanese ships that were moored there. The limpet mines went off just before dawn, by which time the men had safely made their escape. Mission accomplished, they paddled back to rendezvous with the Krait, before sailing home to Australia. They eventually arrived back at Exmouth Gulf on 19 October.

(Right) Australian and British commandos on board the Krait en route to Singapore to sabotage Japanese ships at Keppel Harbour, 1943. Ivan Lyon is in the back row, third from the left. Courtesy of the Australian War Memorial, P00986.001.

The comic is structured into four main parts: the journey to Singapore, preparations for the raid, the process of adding explosives to the Japanese vessels in the harbour, and the men’s subsequent escape after the mines were detonated.

As a comic book aimed at teenage boys, the work is naturally more focused on recounting a thrilling narrative than on historical accuracy. As a result, some events were exaggerated or even added for dramatic effect. The comic book also gets some details wrong. In one panel, the wrong Japanese flag is used. (It should have been the flag with a red circle against a plain white background.) Author and researcher Lynette Ramsay Silver, who has written a number of books on Operation Jaywick, including Deadly Secrets: The Singapore Raids, 1942–45, has also argued that while it is commonly believed that seven vessels were damaged, records can only confirm six, and all but two were put back in service within days.2

Sailing to Singapore

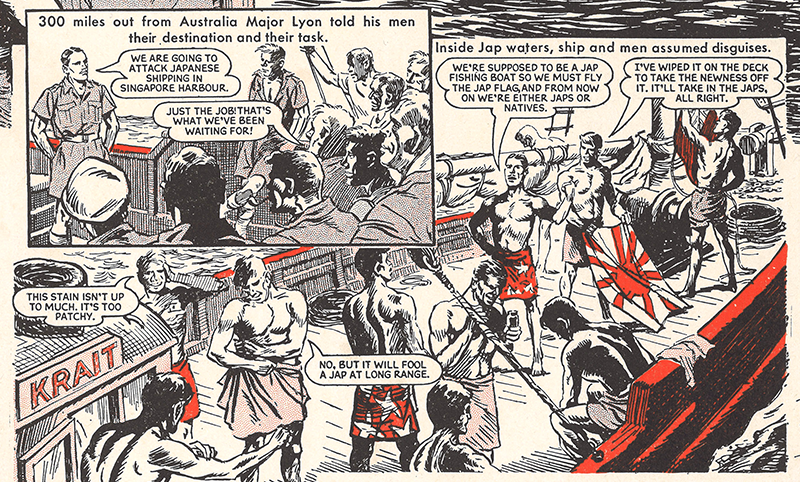

In the comic book, the narrative begins with Lyon informing the men about the details of their mission once they are out at sea.

As they get closer to Singapore, the crew disguise the ship and themselves to avoid detection. “We’re supposed to be a Jap fishing boat so we must fly the Jap flag and from now on we’re either Japs or natives,” says Lyon in the story. The men applied dark brown cream on themselves to look more Asian. According to Silver, the men also switched out of their uniform into sarong, but this is not mentioned in the comic. Instead, the men are depicted shirtless and wearing only a sarong.3

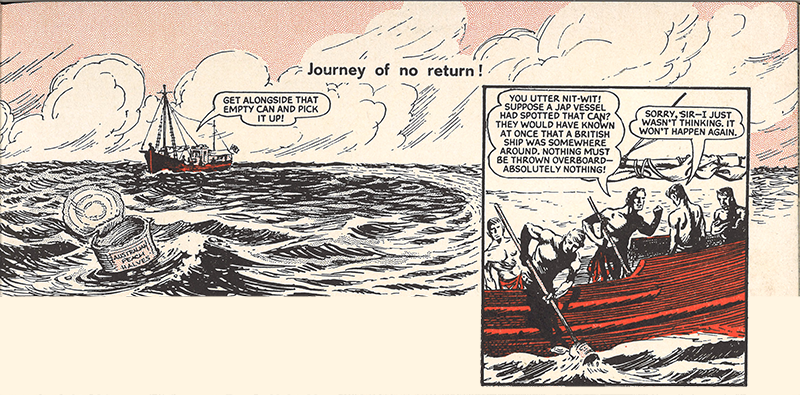

In the story, a man lets down his guard and tosses overboard an empty can with a label indicating that it contained Australian peaches. He receives a tongue-lashing and the Krait has to turn back to retrieve the can in case the label alerts the Japanese to their presence. This is likely to be a narrative device used to illustrate how the men had to be careful about the trash that they disposed of. According to Silver, the tinned food they had did not have labels on them; instead, the cans had identification numbers. A lookout did accidentally drop a hat and a towel into the sea though, which were retrieved.4

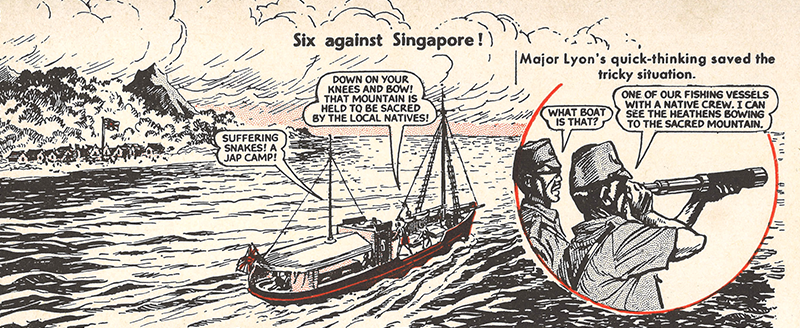

The comic says that after the Krait makes it through the Lombok Strait, it sails past a Japanese base during broad daylight, which means they are likely to be spotted. Lyon instructs the crew to kneel and bow towards the mountain behind the camp as it is considered sacred by the locals. The ruse works, and although spotted, the Krait is presumed to be a Japanese fishing vessel with a native crew. According to Silver, while Lyon did know the area well, she has not come across any mention of such an incident.5

Preparation

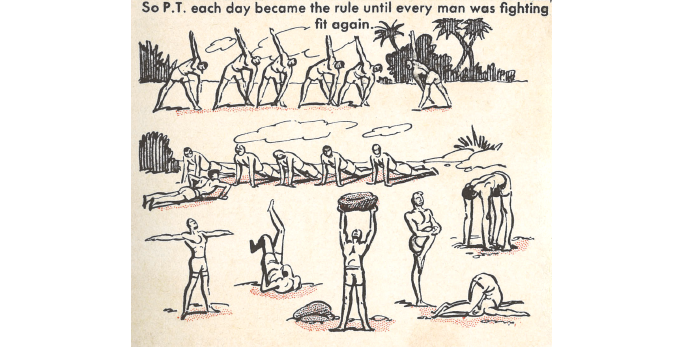

The men eventually reach an island 30 miles (48 km) from Singapore and prepare for their mission. They split up, with the saboteurs paddling in canoes to an island closer to Singapore and are almost detected by a Japanese patrol boat. On the island, they exercise regularly to keep fit while waiting for the plan to attack Japanese ships at Keppel Harbour.

Mines Are Attached

A plan is hatched to attack a convoy that has docked in the harbour. Six men travelling in pairs paddle successfully into the harbour and begin attaching mines to ships.

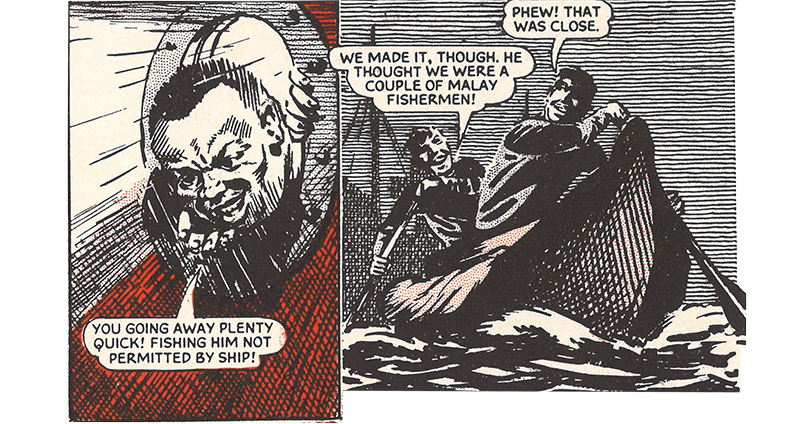

In the comic, a pair have a narrow escape when they are spotted by a Japanese sailor. However, by pretending to be Malay fishermen, they manage to talk their way out of the situation. According to the account in Silver’s book, while the commandos spotted a man looking out of a porthole, apparently staring in their direction, he did not see them and there was no exchange.6

The Escape

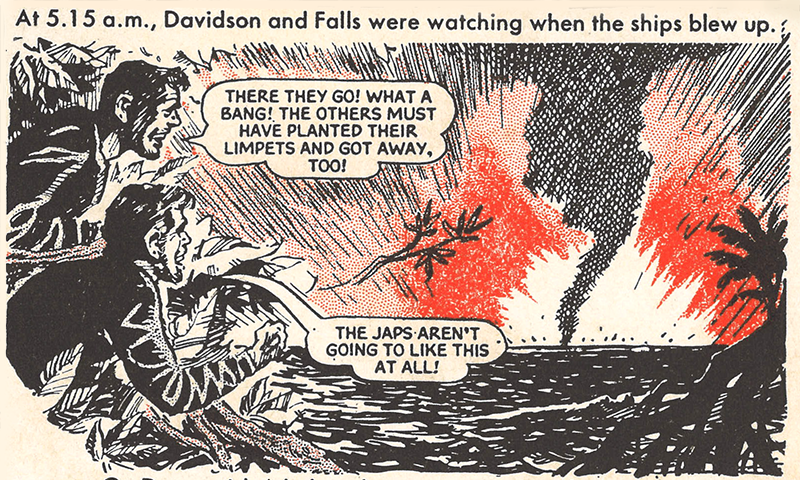

The mines go off just before dawn on 27 September. While this part of the mission is a success, the men must now rendezvous with the others on the Krait to get back to safety.

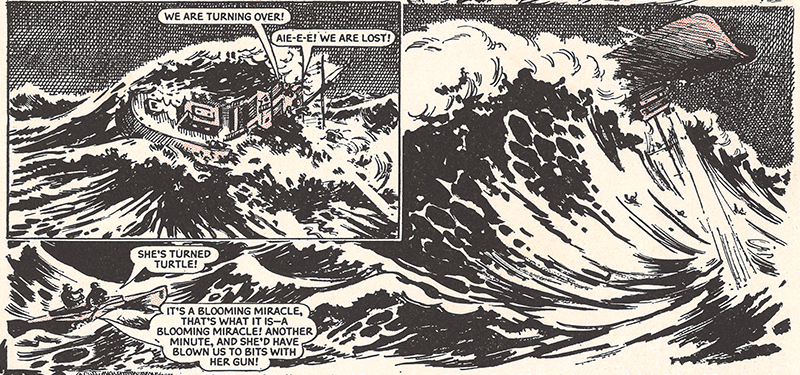

According to the comic book, escaping from Singapore was no easy task. The men first encounter a storm, and then to make matters worse, they are spotted by the Japanese. Fortunately for the commandos, the Japanese ship is wiped out by a sudden, enormous wave caused by the storm. There is no mention of such a dramatic and unlikely incident in Silver’s book.

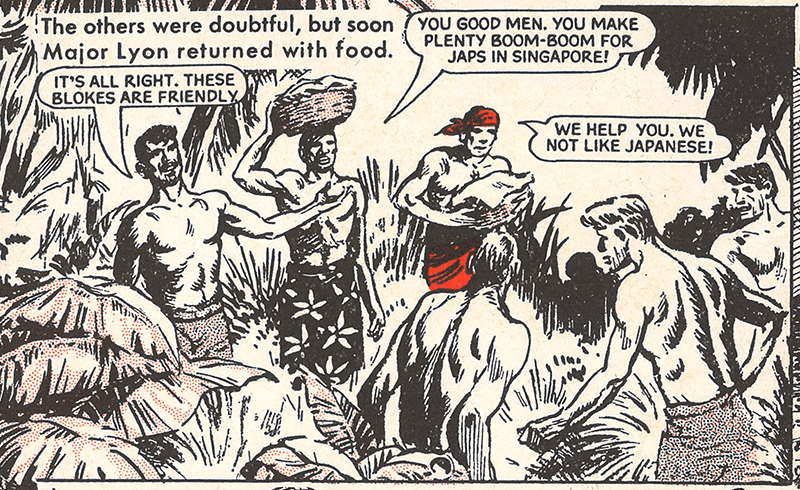

The comic also says that while on an island waiting to be picked by the Krait, the men run out of provisions and have to buy food from the local Malays using gold coins. This story has some basis in truth. According to Silver, while waiting for the Krait, an old Malay man traded his fresh fish for their tobacco and promised to keep them supplied with vegetables and fish.7 But they would not have used gold coins as these would have drawn too much attention.8

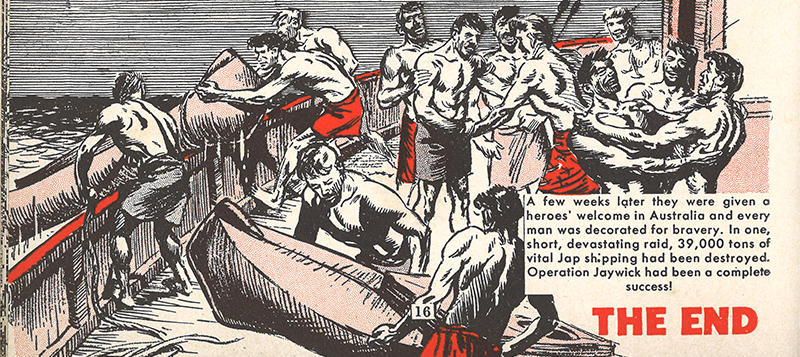

The men are all eventually picked up by the Krait and after a few weeks, they arrive safe and sound in Australia. According to the comic, they are given a heroes’ welcome but in reality, there was no such thing: the men simply held a secret celebration among themselves.9

What Was Left Unsaid

Apart from getting details wrong and inserting events that did not take place, the comic book also leaves out some critical pieces of information. While Operation Jaywick was successful as a commando operation, civilians in Singapore paid a large price.

According to Silver, the raid remained a top secret that was revealed only after the war had ended. The Japanese believed that it had been the handiwork of people in Singapore.10 This led to what is now known as the Double Tenth incident. On 10 October 1943, the Kempeitai (Japanese military police) raided the cells holding civilian internees at Changi Prison. A subsequent roundup of suspects across the island included Elizabeth Choy and her husband Choy Kan Heng.

Out of the 57 internees and civilians who were taken away, interrogated and tortured, 15 died. Those who survived served long prison sentences at either Outram Jail or Changi Prison. Elizabeth Choy, recognised today as a war heroine, was released only after 200 days of starvation and repeated torture, while her husband was released much later.11

Lyon subsequently died in a similar operation, which took place a year later on 10 October 1944. Operation Rimau failed as the men were detected before the raid began. Lyon was killed in action, and everyone with him on that mission also died. They were either killed while trying to escape, perished from their injuries while in captivity, or were executed by the Japanese. Lyon’s remains are buried at Kranji War Cemetery in Singapore (plot 27, row A, headstone 14). Most of the other men involved in the mission are also buried in Kranji, though six still lie in unmarked graves in the Riau Islands.12

On 26 September 2013, a ceremony was held in Singapore to commemorate the 70th anniversary of Operation Jaywick. War veterans from Singapore, military personnel from other countries, students and members of the public, along with the Australian and British high commissioners, attended the event.13 As for the fate of the Krait, the vessel is currently berthed at the Australia National Maritime Museum in Sydney, and operated on special occasions or displayed at special events.

Gautam Hazarika grew up in India but moved to Singapore more than 20 years ago. A former banker, Gautam now focuses on his passion, history, and has a collection of books, maps, prints and paintings. He donated The Victor Book for Boys: The Commandos at Singapore to the National Library Board in April 2023.

Gautam Hazarika grew up in India but moved to Singapore more than 20 years ago. A former banker, Gautam now focuses on his passion, history, and has a collection of books, maps, prints and paintings. He donated The Victor Book for Boys: The Commandos at Singapore to the National Library Board in April 2023.NOTES

-

The Victor Book for Boys was an annual accompaniment to the weekly comic paper, The Victor, which ran from 25 January 1961 to 21 November 1992 (1,657 issues). The majority of the stories in the paper were about the exploits of the British military in World War II. There were 31 annuals altogether and these were published from 1964 to 1994. ↩

-

Lynette Ramsay Silver, Deadly Secrets: The Singapore Raids, 1942–45 (Binda, New South Wales: Sally Milner Publishing, 2010). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 940.5425957 SIL-[WAR]); “SOA, M & Z Special Units, Operation Jaywick Myths,” Lynette Ramsay Silver, AM, MBE, accessed 26 April 2023, https://lynettesilver.com/special-operations-australia/soa-m-z-special-units-operation-jaywick-myths/. ↩

-

The dark brown cream was apparently made by the cosmetics brand, Helena Rubinstein. See Silver, Deadly Secrets, 152. ↩

-

Silver, Deadly Secrets, 153, 157. ↩

-

Lynette Ramsay Silver, email correspondence, 5 April 2023. ↩

-

Silver, Deadly Secrets, 165. ↩

-

Silver, Deadly Secrets, 100. ↩

-

Silver, email correspondence, 5 April 2023. ↩

-

“SOA, M & Z Special Units, Operation Jaywick Myths.” ↩

-

“SOA, M & Z Special Units, Operation Jaywick Myths.” ↩

-

Wong Heng, “Double Tenth Incident,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published January 2021; Bonny Tan, “Elizabeth Choy,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 30 June 2016. ↩

-

Janice Loo, “They Died for All Free Men: Stories from Kranji War Cemetery,” BiblioAsia 18, no. 2 (July–September 2022), 18–25. ↩

-

Andre Yeo and Kelvin Chan, “Commando Attack at Keppel Harbour,” New Paper, 27 September 2014, 14–15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩