Revisiting the Mystery of the Missing Gold Coins

Two ancient gold coins, probably from Aceh, were discovered in Singapore in the middle of the 19th century. Unfortunately, they disappeared a few decades later.

By Foo Shu Tieng

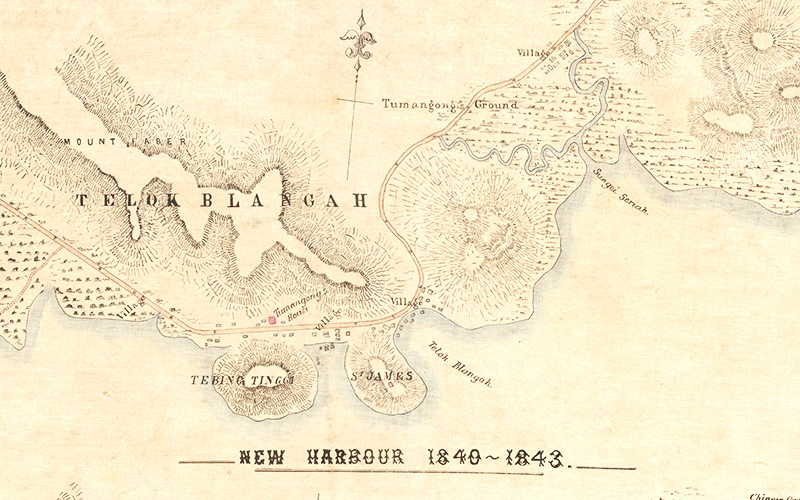

Around 1840, some convict labourers made a startling discovery while building a road to New Harbour (present-day Keppel Harbour) – now Telok Blangah Road and Kampong Bahru Road. While clearing land belonging to Temenggong Daeng Ibrahim near the village of Telok Blangah, they uncovered two ancient gold coins with Jawi inscriptions on them.1

In 1849, these two coins were presented to the Singapore Library – predecessor of the current National Library and National Museum of Singapore – by Straits Settlements Governor William J. Butterworth on behalf of the Temenggong, who had purchased the coins from the convicts.2

In the Singapore Library report of 1849, the lawyer and scholar James Richardson Logan (who founded the Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia in 18473) believed that the two coins were probably from Aceh Darussalam on the island of Sumatra.4 The kingdoms of Aceh and Johor had long vied for economic and political hegemony in the Malay world, with Aceh invading Johor at least six times between 1564 and 1623.5

Acehnese coins may have been a widely accepted foreign currency in Johor from the mid to late 16th century after its conquest by Aceh in 1564.6 During this period, the island of Singapore was under Johor’s jurisdiction and gold coins were most likely used for high value trade or as a marker of status.

The 1849 Singapore Library Report published Logan’s transliteration of the Jawi text inscribed on the coins into Rumi (Romanised Malay). However, the text in the published report does not match any of the recent studies on Acehnese gold, which suggests that the initial reading of the text could be inaccurate.7 At this point, one would need to examine the original artefacts to confirm if the original transliteration was accurate. This, however, is a problem, because the two Singapore Library coins have vanished.

By 1884, the coins were no longer listed in an exhibition catalogue of the Raffles Museum.8 Karl Richard Hanitsch, the first director of the Raffles Library and Museum, wrote an article on the history of the museum published in 1921 where he mentioned that there was a list of artefacts initially associated with the Singapore Library that could no longer be found.9 The coins may have been included in this list.

Based on this information, it appears likely that the coins were lost when the Singapore Library experienced a period of financial difficulties (1861–74).10 (The Crown Colony government subsequently took control of the Singapore Library and established the Raffles Library and Museum in 1874, which eventually became the current National Library and National Museum of Singapore.11)

A check with the National Museum of Singapore in December 2022 confirmed that the two coins are not in their collection.12 The coins are not with the National Library either.

Identifying the Gold Coins

To establish if the coins were really from Aceh, new readings of the inscriptions on the coins should be made and, more importantly, tested to see if these are reasonable alternatives. To do this, I sought help from colleagues, Librarian Toffa Abdul Wahed and Senior Librarian Mazelan Anuar, who transliterated Logan’s Rumi text back into Jawi and then compared the Jawi text with those from other Acehnese coins. In doing this, we tried to see if we could find a plausible alternative reading for the Singapore Library coins, based on the assumption that the original transliteration in the report was an inaccurate but still a best-guess effort that relied on the shape of the words.

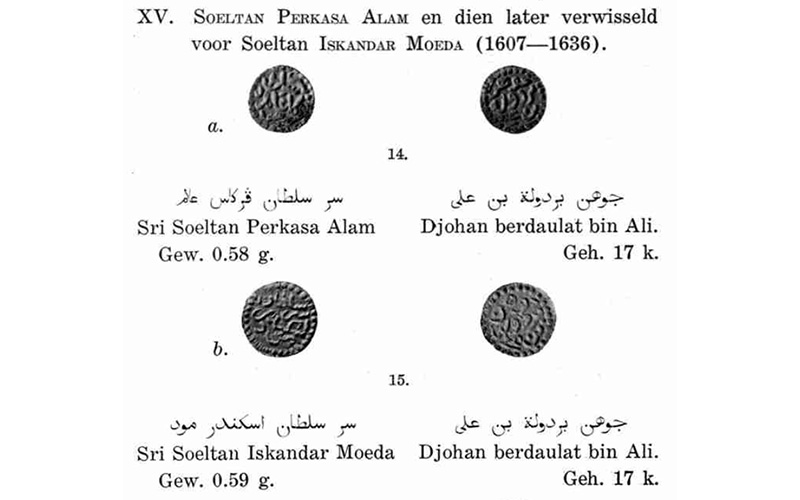

Using this method, Toffa suggested that the obverse side (the side with the principal design) of one of the coins could have been inscribed with the words “Sri Sultan Iskandar Muda” (سري سلطان اسکندر مودا), which means “Auspicious Sultan Iskandar the Young”.13 The Singapore Library’s original transliteration was “Sultan Sri Sikandar Mahbud”. The reverse side possibly had the text “Johan Berdaulat bin Ali” (جوهن برداولت بن علي), which means “Sovereign Champion son of Ali”.14 (In the Singapore Library report, it was “Tuhan Nardubah bin Ali”). If our alternative transliteration is correct, this would suggest that the coin, which we will call Coin A, was minted during the reign of Sultan Iskandar Muda (r. 1607–36) of Aceh.

During Sultan Iskandar Muda’s reign, Aceh’s empire was at its peak – extending as far as Padang along the west coast and Siak along the east coast of Sumatra, and stretching all the way to Kedah, Perak, Pahang and Johor on the Malay Peninsula.15 The coins could have ended up in Singapore at some point after Aceh invaded Johor in June 1613 and November 1615.16

As for the second coin (Coin B), according to Mazelan, a plausible alternative transliteration for the text on the obverse side is “Sri Sultan Perkasa Alam” (سري سلطان ڤرکاس عالم), which means “Auspicious Sultan Courage of the World”. The Singapore Library report had the text as “Sri Sultan Sha Alam Mirsab”. The inscription on the reverse side also bears an inscription that could again be “Johan Berdaulat bin Ali” instead of “Tuhan Nardubah bin Ali”. One of the names that Sultan Iskandar Muda used during the earlier years of his reign was Sri Sultan Perkasa Alam.17 This alternative transliteration suggests that the second coin was also minted during Iskandar Muda’s reign.

However, it should be noted that there are also several other coins that are similar to Coin B, inscribed with “Alam” on the obverse and variations of “Johan Berdaulat” on the reverse.18 Further research is required before we can ascertain the identity of the sultan whose name has been inscribed on Coin B. In order to narrow down the time period of Coin B, researchers may be required to study the primary sources of the lineage of Acehnese rulers which are often complex and contested, while keeping in mind the gaps between the written word and material evidence for early Islamic kingdoms in the region.19

Studies do suggest that Sultan Iskandar Muda was the first ruler from Aceh Darussalam to bear the title of Johan Berdaulat, which is inscribed on coins minted during his reign. If Coin B was indeed Acehnese, his reign would present the upper time limit for when the coin would have been minted.20

Transliterations of Coin A

| Coin A | Original Rumi transliteration by James Richardson Logan (published in the 1849 Library Report) | Transliteration of the Rumi text to Jawi | Possible alternative Jawi text (based on text on Acehnese coins) | Transliteration of alternative Jawi text into Rumi |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sultan | سلطان | سري سلطان | Sri Sultan | |

| Obverse | Sri Sikandar | سري سيکندر | اسکندر | Iskandar |

| Mahbud | محبود | مودا | Muda | |

| Tuhan | توهن | جوهن | Johan | |

| Reverse | Nardubah | نردوبه | برداولت | Berdaulat |

| bin Ali | بن علي | بن علي | bin Ali |

Transliterations of Coin B

| Coin B | Original Rumi transliteration by James Richardson Logan (published in the 1849 Library Report) | Transliteration of the Rumi text to Jawi | Possible alternative Jawi text (based on text on Acehnese coins) | Transliteration of alternative Jawi text into Rumi |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sri Sultan | سري سلطان | سري سلطان | Sri Sultan | |

| Obverse | Sha Alam | شاه عالم | ڤرکاس عالم | Perkasa Alam |

| Mirsab | مرسب | |||

| Tuhan | توهن | جوهن | Johan | |

| Reverse | Nardubah | نردوبه | برداولت | Berdaulat |

| bin Ali | بن علي | بن علي | bin Ali |

Acehnese Gold Coins

In 17th-century Aceh, gold coins were known as mas, with one gold coin being equivalent to one mas.21 During Sultan Iskandar Muda’s reign, four mas were the equivalent of one Spanish dollar (a silver coin; also known as a “Piece of Eight”).22 The sultan was known to have issued a decree recalling older gold coins so that they could be minted into new coins bearing his name. The new coins were issued at a debased rate, meaning that the amount of precious metal in the coin was decreased by adding base metals even though the coin was meant to be worth the same amount. As a result, traders in Aceh were initially reluctant to use them.23

During the reign of Sultan Iskandar Muda’s daughter, Sultanah Tajul Alam Safiatuddin Syah (r. 1641–75), there were further orders for the gold coins of preceding sultans to be collected and reissued at a further debased rate.24 Debasing coins was a common practice meant to control production costs, particularly if the price of the precious metal that the coin was made of had increased dramatically. It was also done to increase the amount of currency in the market when there was a shortage of such coins for transactions. The cumulative effect of collecting old coins, minting and reissuing coins over time means that coins from Sultan Iskandar Muda’s reign are likely to be rarer than those from later rulers.

In addition, imitations of Acehnese gold coins that were underweight and irregular were also circulating at one point. Unfortunately, without being able to examine the two gold coins found in Singapore, we cannot establish if they were originals or imitations.25

But whether or not they were original, the gold coins unearthed in Telok Blangah are significant. For a long time, these gold coins were the only known Islamic gold coins reported to have been found in Singapore until the discovery of a Johor gold coin recovered during a 2015 excavation at Empress Place.26

Chinese Coins in Singapore

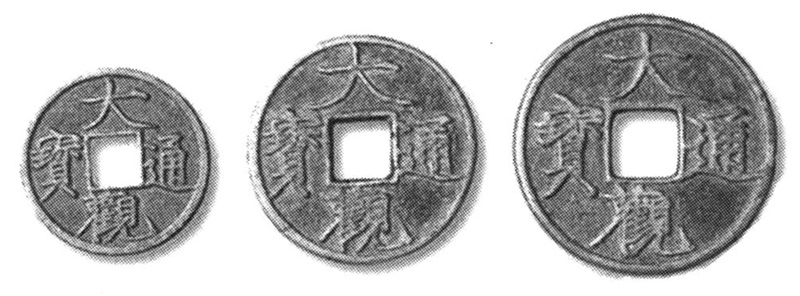

As exciting as they are, the two Acehnese gold coins are not the oldest coins to have been found in Singapore. Chinese coins that date as far back as the Tang dynasty (7th to 10th centuries) have been discovered here, such as at the Parliament House Complex excavation conducted in 1994–95.27

Indeed, Chinese coins were among the first ancient coins to be uncovered. In 1819, Acting Engineer Henry Ralfe stumbled upon a cache of ancient Chinese coins while clearing an elevated spot of a wall surrounding the ancient city of Singapura, thought to be along present-day Stamford Road.28 Reverend Samuel Milton of the London Missionary Society in Singapore identified one of the coins to have come from the reign of Emperor Huizong (宋徽宗, r. 1101–25) of the Northern Song dynasty.29 The other coins had crumbled to dust, likely due to severe metal oxidation and corrosion. Coinage dating to Emperor Huizong’s reign was notable for the increased production of higher denominated (the three-qian and ten-qian coins) and increasingly debased coins, a sign of worsening inflation during his reign.30

Ralfe’s coin find was presented to the Asiatic Society in Calcutta on 10 March 1820. According to an 1822 publication, Ralfe subsequently donated the coins to the Museum of Asiatick Society in Calcutta. Unfortunately, the Huizong coin may have been stolen from the museum in 1844.31

In 1822, John Crawfurd, the second British Resident of Singapore, discovered three more ancient Chinese coins on Fort Canning Hill, all from the Song dynasty: one dating to the reign of Emperor Taizu (宋太祖, r. 960–76), another to Emperor Yinzong (宋英宗, r. 1063–67), and the final coin to Emperor Shenzong (宋神宗, r. 1067–85).32 These coins were deposited in the Royal Asiatic Society.33

Studies of coins recovered from archaeological excavations at the civic district – specifically, the Parliament House Complex (1994–95), Singapore Cricket Club (2003) and St Andrew’s Cathedral (2003–04) sites – have identified at least 30 more coins dating to the reign of Emperor Huizong, and they complement other coin finds reported in the colonial period.34 The research into these archaeological finds suggests that the majority of coins used in Singapore in the 14th century appear to be of Chinese origin, largely from the Northern Song period. However, artefacts from other excavations in Singapore are still being processed, and the small sample size from the three excavation sites may be quite different from the eventual larger data set.

Ancient Coins in Southeast Asia

Coins can be important primary sources of history. They can provide information on the people living in Singapore at the time, its trade relations and distribution networks, the economic climate and even power structures within society. The presence of gold coins in Telok Blangah, for instance, adds to the evidence of human activity in the area in the 17th century.

This material evidence complements an account by Jacques de Coutre, a Flemish gem trader, who mentioned seeing vessels used by the orang laut (“sea people”; an indigenous people who fish and collect sea products) at the entrance of the straits near Isla de Arena (now the island of Sentosa) in 1595. He also talked about the activities of the Shahbandar, an official who supervised the collection of customs duties, the warehousing of imports, and who looked after the ruler’s investments in the area.35

The academic study of coins and other forms of money is conducted mainly by anthropologists, archaeologists, monetary historians and numismatists, who approach the materials in different ways to make sense of the artefacts and their history. While coins are generally used as a method of payment, they have also been used as tokens, commodities and even for magic purposes and/or as part of rituals.36

While coinage is a well-studied subject in South Asia and East Asia, the situation is different in Southeast Asia. In this region, many questions still remain regarding the supply, time period and distribution of coinage. According to Zhou Daguan (周达观), a Yuan-dynasty diplomat who visited the capital city of Angkor in 1296–97, the Khmer Empire (9th to 15th centuries) did not use coinage. Instead, items such as rice, grain and Chinese goods were used for small transactions, cloth for medium-sized transactions, and silver and gold for large transactions.37

One theory why coinage was not popular in Angkor during that period is that surplus wealth may have been redistributed through religious rather than political networks. Another probable reason was the high cost of production and the cost of maintaining mints.38

The Kingdom of Srivijaya (7th to 14th centuries) based in South Sumatra, however, may have used coins with a sandalwood flower design and “chopped off lumps of silver” for business transactions during certain periods.39 Since the founder of Singapura, Sang Nila Utama, was said to be a prince from Palembang, the capital city of Srivijaya, it is possible that ancient Singapore also used coins for transactions in the 13th and 14th centuries.

Interestingly, the Chinese trade sources that describe ancient Singapore did not mention the use of coins for trade. One of the commodities mentioned instead was “red gold” (紫金), which may refer to gold treated with a liquid called sepuh (a mixture of “alum, saltpetre, blue stone, and other materials that can turn gold into a darker colour”).40 Other commodity items used for trade included blue satin, cotton prints, porcelain, and iron items such as cauldrons or pieces of iron.41

This trading arrangement, however, could have been different for merchants who traded in Javanese goods, or for merchants after the Majapahit invasion of the island in the mid-14th century. The Majapahit Empire (1293–1478/1519) based in East Java was known to have used imported Chinese coins and most likely introduced these coins to Singapore for official use and trade.42

Chinese coins were exported to island Southeast Asia in small quantities during the reign of Emperor Renzong (宋仁宗, r. 1020–63) of the Song dynasty. After an export embargo was lifted in 1074, Chinese copper coins began circulating in ports along the Strait of Malacca in larger quantities.43 The Song government had first priority on the purchase of foreign goods and paid foreign merchants with Chinese coins through a system called bomai (博买). Once the coins found their way to Southeast Asia, they were often used to trade for Javanese products.44

At one point, the East and Southeast Asian demand for Chinese coinage became so great that commodities were apparently sold at “one-tenth of their value” in order to obtain the coins.45 This eventually caused a severe shortage of copper and copper coins in China. An edict by Emperor Ningzong (宋寧宗, r. 1195–1224) in the 13th century, for example, banned the use of metal currencies for government purchases, and goods such as silk, porcelain and lacquer were used as substitutes.46 (This ban was subsequently lifted.)

The Missing Gold Coins

While Chinese bronze alloy coins were used as small denomination currency in the 14th century, 17th-century Islamic gold coins in Singapore were probably used as a high-denomination currency for large trades. Alternatively, these Islamic gold coins could also have functioned as status symbols or even as grave markers.

Unfortunately, many vital questions still remain regarding the gold coins of Telok Blangah. Were they indeed Acehnese coins? How did they disappear and where are they now? These coins could be in a dusty drawer or forgotten safety deposit box somewhere in Singapore, waiting to be rediscovered. Or they may have already left our shores like the Chinese coins from the discoveries by Ralfe and Crawfurd. We do not know the answers to these questions, but with further research, maybe someday, we will be able to find out more.

Foo Shu Tieng is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, and works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia collections. Her responsibilities include collection management, content development as well as providing reference and research services.

Foo Shu Tieng is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, and works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia collections. Her responsibilities include collection management, content development as well as providing reference and research services.Notes

-

Marianne Teo, “Numismatics,” in Treasures from the National Museum Singapore (Singapore: National Museum Singapore, 1987), 82. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 708.95957 TRE); Gracie Lee, “Collecting the Scattered Remains: The Raffles Library and Museum,” BiblioAsia 12, no. 3 (April–June 2016): 39–45; J.C. Smith, “The Fifth Report of the Singapore Library,” in Reports of Singapore Library, 1844–60 (Singapore: G.M. Frederick, 1849), 10–12; reproduced in R. Hanitsch, “Raffles Library and Museum, Singapore,” One Hundred Years of Singapore, vol. 1, ed. Walter Makepeace, Gilbert E. Brooke, Roland St. J. Braddell (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1991), 531–33. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 ONE). The land in Telok Blangah belonging to the Johor Sultanate in the vicinity of New Harbour is seen in a map by W.J. du Port. See The National Archives, UK, “Plan of New Harbour, Singapore,” 1871, map. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. D2016_000201). Daeng Ibrahim was formally recognised as Temenggong by the Bendahara of Pahang in 1841. C.M. Turnbull, The Straits Settlements 1826–67: Indian Presidency to Crown Colony (London: Athlone Press, 1972), 275. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 TUR-[HIS]) ↩

-

Smith, “The Fifth Report,” 10; Lionel Milner Angus-Butterworth, General J.W. Butterworth, C.B. (1801–1856), Governor of Singapore (Buxton: L.M. Angus-Butterworth, 1978), 9. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 942.080924 BUT.A) ↩

-

Ang Seow Leng, “Logan’s Journal,” BiblioAsia 11, no. 4 (January–March 2016): 28–29. ↩

-

Smith, “The Fifth Report,” 10–11. ↩

-

Leonard Y. Andaya, The Kingdom of Johor 1641–1728: Economic and Political Developments (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1975), 22–23. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.51 AND–[GH]) ↩

-

Bank Negara Malaysia, Malaysian Numismatic Heritage (Malaysia: The Money Museum and Art Centre, Bank Negara Malaysia, 2005), 89. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 332.49595 BAN) ↩

-

Smith, “The Fifth Report,” 10–11; Robert Sigfrid Wicks, A Survey of Native Southeast Asian Coinage Circa 450–1850: Documentation and Typology (Ithaca: Cornell University, 1983), 258–72. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 737.4959 WIC); J. Hulshoff Pol, “De Gouden Munten (Mas) Van Noord-Sumatra,” Jaarboek van het Koninklijk Nederlandsch Genootschap voor Munt-en Penningkunde XVI (1929): 1–32, https://jaarboekvoormuntenpenningkunde.nl/jaarboek/1929/1929a.pdf. ↩

-

National Museum (Singapore), Catalogue of Exhibits in the Raffles Museum Singapore, 1884 (Singapore: Late Mission Press, 1884), 192, https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/138313. ↩

-

Hanitsch, “Raffles Library and Museum, Singapore,” 531–33. ↩

-

Smith, “The Fifth Report, 10, 20; Charles Burton Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore (With Portraits and Illustrations), vol. II (Singapore: Fraser & Neave Limited, 1902), 500. (From BookSG); “The Singapore Library,” Straits Times, 30 May 1863, 2; “Singapore Library,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 18 June 1863, 3; “Untitled,” Straits Times, 24 January 1874, 3. (From NewspaperSG); Bonny Tan and Heirwin N. Nasir, “Singapore Library (1845–1874),” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 2016. ↩

-

Hanitsch, “Raffles Library and Museum, Singapore,” 531–33, 541; Preservation of Sites and Monuments, National Heritage Board, “National Museum of Singapore,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 31 August 2015. ↩

-

Iskander Mydin, email correspondence, 7 December 2022. ↩

-

Amirul Hadi, Islam and the State in Sumatra: A Study of Seventeenth-Century Aceh (Leiden: Brill, 2004), 49. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 322.1095981 HAD) ↩

-

Teuku Iskandar, “A Document Concerning the Birth of Iskandar Muda,” Archipel 20 (1980): 214, https://doi.org/10.3406/arch.1980.1602; Andaya, The Kingdom of Johor 1641–1728, 22. ↩

-

Andaya, The Kingdom of Johor 1641–1728, 22. ↩

-

Peter Borschberg, “Urban Impermanence on the Southern Malay Peninsula: The Case of Batu Sawar Johor (1587–c.1615),” Journal of East-Asian Urban History 3, no. 1 (2021): 75–76, https://doi.org/10.22769/JEUH.2021.3.1.57. ↩

-

Teuku Iskandar, “A Document Concerning the Birth of Iskandar Muda,” 221–22; Amirul Hadi, Islam and the State in Sumatra, 49. ↩

-

T. Ibrahim Alfian, Mata Uang Emas Kerajaan-Kerajaan di Aceh (Banda Aceh: Proyek Rehabilitasi dan Perluasan Museum Daerah Istimewa Aceh, 1979), 46–47. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Malay RSEA 737.495981 ALF) ↩

-

John R. Bowen, “Narrative Form and Political Incorporation: Changing Uses of History in Aceh, Indonesia,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 31, no. 4 (October 1989): 681–90. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); Hasan Muarif Ambary, Menemukan Peradaban: Jejak Arkeologis dan Historis Islam Indonesia (Jakarta: Logos Wacana Ilmu, 1998), 55–58. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Malay RSEA 959.8015 AMB) ↩

-

Hulshoff Pol, “De Gouden Munten (Mas) Van Noord-Sumatra,” 18; T. Ibrahim Alfian, Mata Uang Emas, 46–47. ↩

-

Denys Lombard, “Politik Perdagangan dan Bangsa-Bangsa Asing,” in Kerajaan Aceh: Zaman Sultan Iskandar Muda (1607–1636) (Jakarta: Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia and École française d’Extrême-Orient, 2007), 155. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Malay RSEA 959.81 LOM) ↩

-

K.F.H. Van Langen, “De Inrichting van het Atjehsche Staatsbestuur onder het Sultanaat,” Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde van Nederlandsche-Indië Deel 37, 3de (1888): 430; (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); K.F.H. Van Langen, Susunan Pemerintahan Aceh Semasa Kesultanan, trans. Aboe Bakar (Banda Aceh: Pusat Dokumentasi dan Informasi Aceh, 1986), 67 (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Malay RCLOS 959.81 LAN); Sim Ewe Eong, “Ringgit,” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 47, no. 1 (225) (1974): 59 (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website). For a summary of the regional use of Acehnese currency for trade in the Strait of Malacca, see Ahmad Jelami Halimi, “Kewangan dan Mata Wang,” in Perdagangan dan Perkapalan Melayu di Selat Melaka Abad Ke-15 Hingga Ke-18 (Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, 2006), 148–49, 154. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. R 387.5409595 AHM) ↩

-

Lombard, “Politik Perdagangan,” 155–59. ↩

-

Van Langen, “De Inrichting van het Atjehsche Staatsbestuur,” 430; Van Langen, Susunan Pemerintahan Aceh, 68. ↩

-

Wicks, A Survey of Native Southeast Asian Coinage Circa 450–1850, 272. ↩

-

“Gold Coin,” SG Bicentennial, 12 March 2019, https://www.sg/sgbicentennial/the-bicentennial-experience/emporium/gold-coin/. ↩

-

Brigitte Borell, “Money in 14th Century Singapore,” in Southeast Asian Archaeology 1998: Proceedings of the 7th International Conference of the European Association of Southeast Asian Archaeologists Berlin, 31 August–4 September 1998, ed. Wibke Lobo and Stefanie Reimann (Hull: Centre for Southeast Asian Studies, University of Hull, 2000), 2. ↩

-

“Literary and Philosophical Intelligence,” The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British India and Its Dependencies X (1820): 477, https://archive.org/details/dli.ministry.09920/page/291/mode/2up; Mok Ly Yng, “The Bute Map,” in On Paper: Singapore Before 1867 (Singapore: National Library Board, 2019), 66–71. (From BookSG); John N. Miksic, “Introduction: The Archaeology of Singapore,” in Singapore & the Silk Road of the Sea 1300–1800 (Singapore: NUS Press and National Museum of Singapore, 2013), 7–8. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 MIK-[HIS]); Kwa Chong Guan, et al., Seven Hundred Years: A History of Singapore (Singapore: National Library Board, 2019), 33. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 KWA-[HIS]) ↩

-

Emperor Huizong was mentioned in the original text as Huing Tsung. See “Coin Discovered at Singapore,” Calcutta Journal, or Political, Commercial, and Literary Gazette, 14 February 1820, 307; later reproduced in “Sincapore,” The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British India and Its Dependencies X (1820): 198, 292, https://archive.org/details/dli.ministry.09920/page/291/mode/2up; Patricia Buckley Ebrey, Emperor Huizong (Cambridge, Massachussetts: Harvard University Press, 2014), xi. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. R 951.024092 EBR). This find is also discussed in Clement Liew and Peter Wilson, A History of Money in Singapore (Singapore: Talisman Publishing Pte Ltd, 2021), 12–13. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 332.4095957 LIE) ↩

-

Ebrey, Emperor Huizong, 329–37; Li Kangying, “A Study on Song, Yuan and Ming Monetary Policies Within the Context of Worldwide Currency Flows During the 11th–16th Centuries and Their Impact on Ming Institutions.” In The East Asian Maritime World 1400–1800: Its Fabrics of Power and Dynamics of Exchanges, ed. Angela Schottenhammer (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2007), 113. ↩

-

“Literary and Philosophical Intelligence,” 477; “List of the Donors and Donations to the Museum of the Asiatick Society,” Asiatick Researches 14 (January 1820): Appendix III, 6M, https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/133120#page/553/mode/1up; “Contents of the Fourteenth Volume,” Asiatick Researches 14 (January 1820): front matter, https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/133120#page/7/mode/1up; Vincent A. Smith, “General Introduction,” in Catalogue of Coins in the Indian Museum Calcutta Including the Cabinet of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, vol. I (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1906), xv, https://indianculture.gov.in/rarebooks/catalogue-coins-indian-museum-calcutta-including-cabinet-asiatic-society-bengal-vol-i-1. ↩

-

John Crawfurd wrote about the coins in an entry dated 4 February 1822. The regnal date for the first coin was corrected (Emperor Taizu died in 976 instead of 967 as stated in Crawfurd’s text). See John Crawfurd, Journal of an Embassy from the Governor-General of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China; Exhibiting a View of the Actual State of Those Kingdoms (London: Henry Colburn, 1828), 47. (From BookSG); Denis Twitchett and Paul Jakov Smith, eds., “Table 2: Sung Emperors and Their Reign Periods,” in The Cambridge History of China Vol. 5 Part 1: The Sung Dynasty and Its Precursors, 907–1279 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), xxx. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. R 951 CAM) ↩

-

Miksic, Singapore & the Silk Road of the Sea 1300–1800, 7, 9. Song Ong Siang mentioned that the coins were dug up in 1827 but this may have been the year they were reported or deposited with the Royal Asiatic Society. See Song Ong Siang, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore: The Annotated Edition, annotated by Kevin Y.L. Tan (Singapore: World Scientific, 2020), 3. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 SON-[HIS]) ↩

-

Heng, “Export Commodity and Regional Currency,” 192; John N. Miksic and Goh Geok Yian, “Discussion: Stone, Metal, Organic Materials,” in The Singapore Cricket Club Excavation Site Report, April 2003, https://epress.nus.edu.sg/sitereports/scc; Borell, “Money in 14th Century Singapore,” 4; Clement Liew and Peter Wilson, A History of Money in Singapore (Singapore: Talisman Publishing Pte Ltd, 2021), 12. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 332.4095957 LIE) ↩

-

Peter Borschberg, ed., Jacques de Coutre’s Singapore and Johor 1594–c.1625 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2015), 2–3, 22. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959 COU); Kwa et al., Seven Hundred Years, 89–111. ↩

-

Joe Cribb, Magic Coins of Java, Bali and the Malay Peninsula: Thirteenth to Twentieth Centuries: A Catalogue Based on the Raffles Collection of Coin-Shaped Charms from Java in the British Museum (London: Museum Press, 1999), 65–79. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 737.495982 CRI); Walter William Skeat, Malay Magic, Being An Introduction to the Folklore and Popular Religion of the Malay Peninsula (London: Macmillan and Co., 1900), 409, 441. (From BookSG) ↩

-

I agree with Peter Harris who translated 唐货 (táng huò) as Chinese goods. Other scholars have interpreted the term to mean Chinese coins. Zhou Daguan, A Record of Cambodia: The Land and Its People, trans. Peter Harris (Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 2007), 70. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.6 ZHO); Xia Nai 夏鼐, Zhenla feng tu ji jiao zhu 真腊风土记校注 [Annotation of a Record of Cambodia] (Beijing 北京: Zhong hua shu ju 中华书局, 2000), 146. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Chinese RSEA 959.6 XD) ↩

-

Pamela Gutman, “The Ancient Coinage of Southeast Asia,” Journal of the Siam Society 66, no. 1 (1978): 9–10, https://thesiamsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/1978/03/JSS_066_1c_Gutman_AncientCoinageOfSoutheastAsia.pdf; Eileen Joan Lustig, “Power and Pragmatism in the Political Economy of Angkor” (PhD diss., University of Sydney, 2009), 160–91, https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/5356; Nhim Sotheavin, “Factors that Led to the Change of the Khmer Capitals from the 15th to 17th Century,” カンボジアの文化復興 29 [Cultural Revival in Cambodia], November 2016, 42, 64, 70, https://digital-archives.sophia.ac.jp/repository/view/repository/20201210024. ↩

-

O.W. Wolters, The Fall of Śrīvijaya in Malay History (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1975), 39, 73. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5 WOL); Friedrich Hirth and W.W. Rockhill, Chau Ju-Kua: His Work on the Chinese and Arab Trade in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries, Entitled Chu-fan-chi (2015; repr., St. Petersburg: Printing Office of the Imperial Academy of Sciences, 1911), 60. (From National Library, call no. RBUS 382.0951 ZHA); Kenneth R. Hall, “Indonesia’s Evolving International Relationships in the Ninth to Early Eleventh Centuries: Evidence from Contemporary Shipwrecks and Epigraphy,” Indonesia no. 90 (October 2010): 20, 26. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); Aji YK Putra and Aprillia Ika, “Ini Hasil Perburuan Harta Karun Kerajaan Sriwijaya, dari Lempengan Emas hingga Alat Pencetak Koin,” Kompas.com, 7 October 2019, https://regional.kompas.com/read/2019/10/07/16495411/ini-hasil-perburuan-harta-karun-kerajaan-sriwijaya-dari-lempengan-emas. ↩

-

One use of gold treated with sepuh was for decorative painting, such as on walls and gateways. See Mai Lin Tjoa-Bonatz and Nicole Lockhoff, “Art Historical and Archaeometric Analyses of Ancient Jewellery (7–16th C.): The Prillwitz Collection of Javanese Gold,” Archipel 97 (2019): 51, https://journals.openedition.org/archipel/1018; Stuart Robson, Arjunawiwāha: The Marriage of Arjuna of Mpu Kaṇwa (Leiden: KITLV Press, 2008), 88–89, Canto 16, Section 6, Lines 1–2, http://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/34659. See also Roland Braddell, “Two Notes: Red Gold and Chiamassie,” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 24, no. 3 (156) (October 1951): 157. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

W.W. Rockhill, “Notes on the Relations and Trade of China with the Eastern Archipelago and the Coast of the Indian Ocean during the Fourteenth Century,” Part II. T’oung Pao 16, no. 1 (March 1915): 129–33. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Amelia S., “The Role of Chinese Coins in Majapahit,” in The Legacy of Majapahit: Catalogue of an Exhibition at the National Museum of Singapore, 10 November 1994–26 March 1995, ed. John N. Miksic and Endang Sri Hardiati Soekatno (Singapore: National Heritage Board, 1995), 101. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING q959.801 LEG); Hasan Djafar, Masa Akhir Majapahit: Girîndrawarddhana dan Masalahnya, cetakan kedua (Jakarta: Komunitas Bambu, 2012), 96–131. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Malay RSEA 959.82 DJA) ↩

-

Derek Thiam Soon Heng, “Export Commodity and Regional Currency: The Role of Chinese Copper Coins in the Melaka Straits, Tenth to Fourteenth Centuries,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 37, no. 2 (June 2006): 181–83. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Li, “A Study on Song, Yuan and Ming Monetary Policies, 108; Heng, “Export Commodity,” 185–87; Jan Wisseman Christie, “Javanese Markets and the Asian Sea Trade Boom of the Tenth to Thirteenth Centuries A.D.,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 41, no. 3 (1998): 358–60. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); Hall, “Coinage, Trade and Economy,” 440–41. ↩

-

Jin Xu, Empire of Silver: A New Monetary History of China, trans. Stacy Mosher (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021), 86–87. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RBUS 332.4951 XU) ↩

-

Li, “A Study on Song, Yuan and Ming Monetary Policies,” 110–11. ↩