A Grand Piano's Chequered History

A grand piano that was to be the pride of Singapore failed to silence its critics. The odds, however, were always against it.

By Bernard T.G. Tan

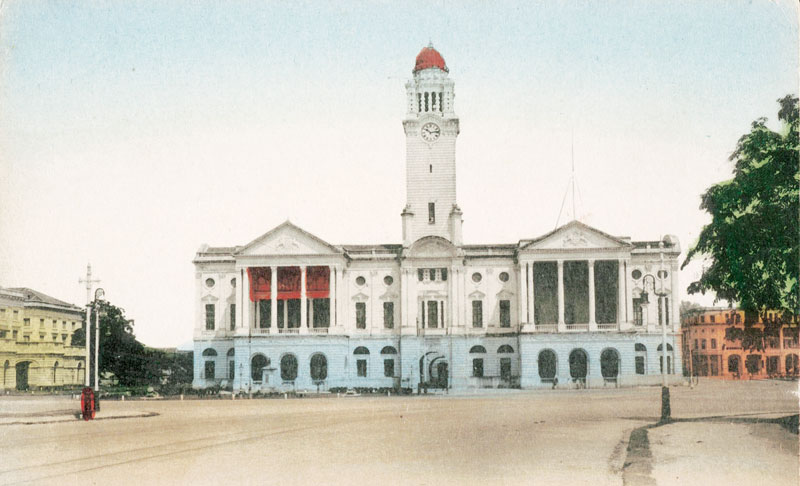

If you visit the National Library Building on Victoria Street, you might spy a nondescript grand piano. Closer perusal reveals obvious wear and tear on its once glossy black sides and lid. A full-sized concert grand made by the English piano manufacturer Chappell, this stately septuagenarian was formerly the principal concert grand at the Victoria Memorial Hall (now Victoria Concert Hall) where famous pianists like Claudio Arrau and Julius Katchen once performed.

This now retired and largely unused instrument, however, hides a colourful and chequered history, which has mostly been forgotten. When the piano was first installed at the Victoria Memorial Hall in 1952, there were high hopes, at least among some, that the instrument would deliver the same sublime tones which the previous piano had become incapable of doing. Sadly, this was not to be; instead, the instrument became the despair of many internationally renowned pianists who had to struggle with its many deficiencies.

The Chappell grand quickly ended up with a reputation it could not shake off. This was, in hindsight, perhaps not surprising. Meant to replace an ageing Steinway concert grand that had been in use since before the war, the Chappell was not the first choice as a replacement. The original intention was to have a brand new, top-of-the-line Steinway concert grand replace the old Steinway. Why that didn’t happen makes for an interesting tale. But let us start at the very beginning.

The Memorial Hall’s Original Steinway

It is not known whether a piano was acquired when the Victoria Memorial Hall was first built in 1905. Newspaper reports of events such as France’s Day Fete in 1919 and the Poppy Day Dance in 1929 record that the well-known British-owned music shop, Moutrie and Co., loaned a piano for both occasions.1 The type or make of piano is not known, but Moutrie (which was still in business in Singapore after the war) did have their own pianos under the Moutrie brand, in addition to importing a number of piano brands from the United Kingdom – such as Chappell – and Europe.

In 1930, the Municipal Commissioners agreed to purchase a Steinway concert grand piano for the Memorial Hall.2 A newspaper report of a recital by the Ukrainian-born British pianist Benno Moiseiwitsch in July 1933 does not explicitly mention a Steinway, but makes it clear that the instrument used by the celebrated pianist fulfilled all the demands made of it in an exhausting recital which included Schumann, Chopin and the Liszt transcription of Wagner’s Tannhäuser Overture.3

A news report of a children’s concert in November 1934 does mention the Steinway though. It describes seven-year-old Florence Wong being lifted onto the chair of the Steinway grand, who then, “by diligent stretching, managed to touch the loud pedal with the tip of one shoe”. The young pianist then gave “a spirited rendering of Christmas Bells (Brinley Richards), for which she was vociferously encored”.4 (She later enjoyed a successful career as an internationally renowned concert pianist better known as Florence Margue-Wong.)

But the vicissitudes of the Second World War and the Japanese Occupation must have taken its toll on the instrument. In September 1950, the Singapore Standard reported that there were plans to “acquire a new concert piano (Steinway) for the Memorial Hall, but it has been held up pending the re-opening of the Steinway factory at Hamburg”.5

Referring to the old Steinway, the Straits Times noted a month later that the piano was 25 years old. “Struck by the hand of a pianist, however skilled, its keys and its strings protest their age and past sorrows.”6

Unfortunately, the plan to buy a new Steinway did not materialise. “Municipal Commissioners have now decided to shelve the purchase of a new piano – a new Steinway concert grand will cost $14,000, and the City Fathers cannot afford that much for the benefit of the musical minority; there are more important matters in dispensing Municipal funds,” wrote the Straits Times.7

A New Steinway?

Fortunately, there appeared to be a change of heart a year later. In November 1951, the Straits Times broke the news that “a new Steinway concert grand piano has been ordered from Hamburg, Germany, for Singapore Victoria Memorial Hall. It will arrive next month”. The City Council (the former Municipal Council) had voted a sum of $17,000 for the piano to replace the existing Steinway, which would be “available for hire” when it was replaced by the new Steinway.8

The order had been placed in October 1951 for a “9 foot concert grand, the famous Model ‘D’ as used and praised by the world’s leading pianists”. However, the delivery had to be made before the end of 1951, giving just two months for the piano to be assembled, tropicalised and delivered from Hamburg. The City Council had also stipulated that the words, “Property of Singapore City Council”, be engraved in gold on the inside of the piano casework.9

The Steinway Company, however, informed its Singapore agent that it was not possible to deliver the piano by the end of 1951 due to “shipping difficulties and problems connected with the tropicalisation of the instrument”. The company promised that delivery would be in mid-January 1952. The City Council went ahead with the payment of $16,428 before delivery. Come February of that year though, there was still no sign of the piano.10

The City Council subsequently cancelled the order with the Hamburg factory when it received a private quotation from the Steinway London office, which was several thousand dollars lower than the amount paid to the Hamburg factory. When the Singapore agent made enquiries, they were told that the London figure was a mistake and the offer was immediately withdrawn by Steinway. Although the agent offered a five percent reduction in the original amount of $16,428, the City Council decided to cancel the order, and the model “D” Steinway – built, engraved with the City Council’s name and ready for delivery to Singapore – never left Hamburg, according to the Straits Times.11

The Chappell Substitute

In January 1952, the City Council decided to purchase a concert grand piano manufactured in England instead, pointing to the fact that the BBC in the Festival Hall in London had used an English-made Chappell concert piano. An order was placed for the same make of piano at a cost of $9,800, with delivery in about nine months.12

By this time, the existing Steinway was showing its age. According to the Straits Times, during French pianist Germaine Mounier’s recital in February 1952, an official from the Singapore Chamber Ensemble had to announce that “owing to the deficiencies of the instrument, Mme. Mounier regrets that she will be unable to play Debussy’s ‘L’isle Joyeuse’ as advertised in the programme”.13

The Chappell eventually arrived by sea on 12 September 1952. Such was the interest in the piano that it was unpacked from its crate in the presence of the press and the superintendent of the Victoria Memorial Hall and Theatre, K.C. Yap. “It’s a relief from the constant criticisms held by the public at the City Council for lack of a good piano,” he said. “I hope everybody will be happy. After all the public is entitled to insist that the City’s public Hall should possess a first class piano.”14

Was it actually a first class piano though? Charles Thornton Lofthouse, an authority on Bach, had played briefly on the Chappell on the day it arrived. When asked to compare between the old Steinway and the new Chappell, his response was: “I am sorry it is not a Steinway.”15

Negative Reviews

The first official use of the new Chappell grand in Singapore appears to have been at a concert for schools organised by the Singapore Chamber Ensemble on 17 September 1952.16 No mention was made about the quality of the instrument, but it was a school concert after all.

The first real test was to come in January 1953, when it was used in a recital by Mounier, about four months after the piano arrived in Singapore. It was, apparently, not a success. Following the concert, a reader wrote a scathing letter to the Straits Times, questioning the wisdom of replacing a Steinway with a Chappell. “During the first half of the programme, it was pitiful to have the pianist demanding a big tone from her instrument and using every resource of her art to obtain it, when only anaemic tinklings were forthcoming.”17

After the interval, Mounier switched back to the old Steinway and the improvement was “a revelation to all who were present”. “[O]ne could begin to hear something like a real piano tone”, and as a result of the change, the pianist apparently “responded with a performance which could fairly be called inspired; and the audience, lukewarm before, gave her an enthusiastic and well-deserved acclamation after the interval”. Noted the letter writer ruefully: “We have tried to economise and have spent $9,000 in acquiring a new piano which is not even equal to the old one.”18

This was just the beginning of a long litany of complaints about the quality of the Chappell. For his series of recitals three months later, the Hungarian pianist Louis Kentner had chosen a repertoire that was designed to “demonstrate his enormous control over the more dynamic tonal resources of the piano”. The Chappell, however, did not perform up to standard on the first night, with music critics describing the tone of the piano as “too woolly” for Kentner’s majestic touch.19

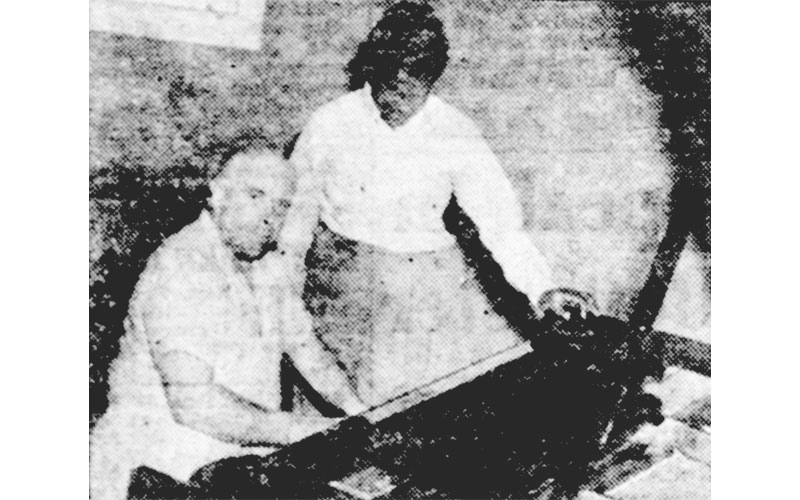

Experienced piano-tuner J.A. Riddell was brought in to improve and brighten up the tone of the Chappell. Unfortunately, it appeared that the brightening went a bit too far. After Kentner’s second recital, music critics said that “the ‘wool’ had been replaced by ‘tin’”.20 “I was shocked out of my wits the moment I touched [the piano]. It was simply appalling. I really thought that a knife or a nail had been left in it in the way a surgeon might accidentally leave a swab in the patient’s abdomen,” said Kentner.21

A distressed Riddell, who had warned Kentner that the piano was at “a critical point”, was awakened by an urgent telephone call during the concert and rushed to the Memorial Hall only to find that the concert was virtually over. He lamented that had he been phoned earlier, he could have “obliterated the problem” in two minutes.22

After the concert, Riddell worked on the piano to remove the brightness and then subsequently spent many hours testing the piano again. While seated at the Chappell piano, he declared to the press: “I’ve done everything that is humanly possible. If it’s not right for Prof. Kentner’s last concert I’ll eat it.”23

Kentner himself “took no chances” for his third and final recital, spending the entire morning testing the Chappell before that night’s concert, and making sure that “it was as good as it could be”. Declaring that “you can’t make a Steinway out of a Chappell”, he was satisfied that the piano was back to what it had been at his first recital.24

A.A. Roff, the manager of Moutrie and Co., the Singapore agent for Chappell, subsequently defended the instrument on the grounds that the piano had not been played enough beforehand. As Roff explained, “A piano needs a good deal of use before it acquires the ‘right’ tone.” He did, however, acknowledge that “[t]here is a difference of about $8,000 in the price of a Chappell and a Steinway, so you can’t expect them to be the same”.25

In subsequent years, a number of internationally renowned pianists performed at the Victoria Memorial Hall. Among them was English pianist Solomon, who was on a Far East tour in November 1953, and celebrated Hungarian virtuoso Bela Siki in November 1954. According to the Singapore Standard, the Solomon concert in November 1953, at least, relied on the old Steinway (which appeared to have had an overhaul) rather than the new Chappell. The Steinway was described as a “great asset” and that “apart from the occasional twang in the middle octaves it sounded fine”.26

American Julius Katchen, one of the world’s most celebrated pianists, gave a recital at the Memorial Hall on 16 January 1955, which was partially broadcast live by Radio Malaya.27 He was here as a judge for the finals of the Singapore Musical Society’s pianoforte competition, whose open section was won by 18-year-old Yu Chun Yee.28 (Chun Yee later became a professor of piano at the Royal College of Music.) Thankfully, Katchen did not perform on the “much derided” Chappell grand but on the older Steinway that the Chappell was supposed to replace.

“The [Chappell] piano now reposes under a dustsheet, a silent monument to the proverb ‘Penny wise, pound foolish’,” a reader wrote to the Straits Times. “What an everlasting pity we could not have heard Katchen on a new Steinway, at whatever the cost.”29 Incidentally, Katchen returned to Singapore in July 1957 and performed at the Anglo-Chinese School’s Lee Kuo Chuan Auditorium, a concert I was fortunate enough to have attended.30 That day, Katchen played on the school’s Steinway concert grand, which had been acquired in 1951 and inaugurated by the Shanghai pianist Feng Jia Bei-Tseng.31 The fact that a mere school hall had a Steinway while the City Council went with a cheaper Chappell spoke volumes.

A Cross Between a Cooking Pot and a Frying Pan

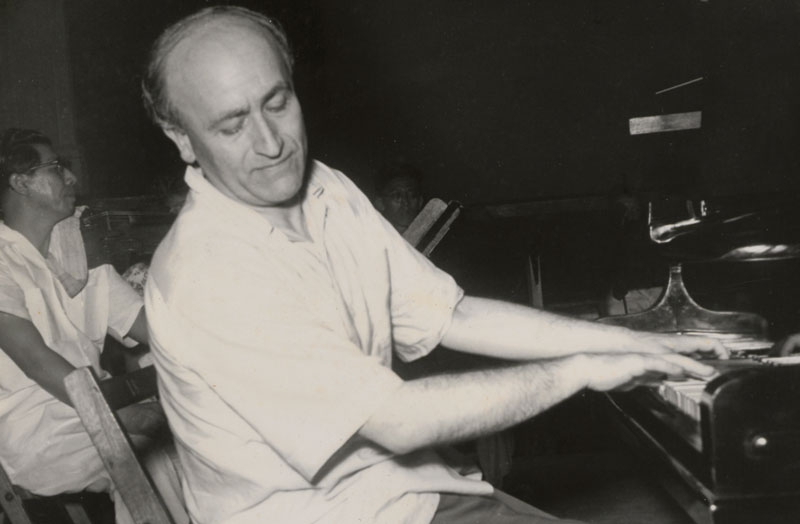

Things came to a head when the great Chilean pianist Claudio Arrau gave a recital at the Victoria Memorial Hall in November 1956. One would have thought that after the many mishaps with the Chappell, another piano would have been used instead for a pianist of Arrau’s stature. Somewhat inexplicably, Arrau performed on the infamous Chappell.

After his concert, Arrau did not mince his words. “I consider it my duty to tell you this. It was outrageous – the piano at the Victoria Memorial Hall. I hate calling it a piano. It was more a cross between a cooking pot and a frying pan. The keys kept on jamming… sometimes I wished I had a plier, a crowbar or something to jack them up.” When asked whether his performance was affected, he declared: “Not at all, I considered it a great challenge… to be able to play on anything.” Arrau said he had been impressed with the “brand new piano” in Kuala Lumpur, and was “very, very sad that Singapore could not get a new one too”.32

It thus came as no surprise that, barely a week after Arrau’s concert, the Japanese pianist Yoko Kono was loaned a new Steinway for her recital. Keller Piano made the offer after learning about her disappointment over the old piano (presumably the Chappell).33

A few months later, in January 1957, the New Zealander pianist Richard Farrell gave a recital, apparently using the old Steinway. It may have been thoroughly overhauled and refurbished after Kono’s comments, for the Straits Times mentioned that “[f]or two hours last night, Richard Farrell’s audience at the Victoria Memorial Hall forgot all arguments about that ‘frying pan’ piano. The Steinway was overhauled recently and it could have had no better friend to introduce its new-found life to critical Singapore”.34

Arrau’s biting remarks about the “frying pan” Chappell piano was likely the final straw. In January 1957, the City Council decided to buy two Steinways: a concert grand for around $18,000 and an upright for more than $3,000. The former would be placed on the stage and the latter in the orchestra pit.35

The plan was for the Chappell to be moved to a new practice theatre being built in the Victoria Theatre, which was undergoing major renovations. The theatre would be equipped with an air-conditioned piano room costing $3,500. The old Steinway in the Memorial Hall would remain, presumably as a back-up to the new concert grand.36

Before the new concert grand arrived, there were a number of major recitals at the Victoria Memorial Hall, such as those in March 1957 by the British pianist Irene Kohler. For her second recital, the Straits Times reported that she chose to use a small Steinway grand, perhaps loaned by Keller Piano, instead of the dreaded Chappell. Her only complaint was that the Steinway “had not been recently tuned”.37

Chappell Bows Out

On 7 January 1958, the Singapore Standard reported that two Steinway pianos costing $22,000 had arrived from Hamburg. The grand piano was to be played for the first time on 10 January by Singapore pianist Gus Stein, the accompanist for the famed American harmonica player Larry Adler (whom I had been fortunate to hear at one of his many concerts in Singapore, possibly this very one).38

One important concert that took place at the Memorial Hall soon after the Adler concert was a recital on 31 May 1958 by Benno Moiseiwitsch, who had performed in Singapore in July 1933 on the old Steinway. Playing on the new Steinway grand, Moiseiwitsch showed what a truly great romantic pianist he was. “With equal facility he was dramatically decisive in the stark staccato passages and as smooth and as soft as a rose petal in the pianissimo passages,” wrote the Straits Times.39

What of the fate of the Chappell after 1958? It can be assumed that the piano was moved as planned to the practice theatre, which was on the second level of the Victoria Memorial Hall, in the space between the Victoria Theatre and the Memorial Hall. As its name implies, this was a mini theatre with a stage and a small audience area, used by conductor Choo Hoey and the fledgling Singapore Symphony Orchestra for their initial rehearsals.

In 1983, the Chappell was moved to the Bukit Merah Branch Library (later renamed Bukit Merah Community Library and subsequently Bukit Merah Public Library) where it stayed for 35 years and was used for musical programmes. When the library closed in 2018, the piano was transferred to the National Archives of Singapore.40 In November 2022, the Chappell moved again, this time to the National Library Building on Victoria Street.

Today, the Chappell has been given a new lease of life as a public piano. Anyone may sidle up and play on it, whether the piece is “Chopsticks” or Beethoven’s “Appassionata” sonata. While it may look a little worn out, it has been lovingly repaired and retuned and it is now a perfectly serviceable musical instrument. As a public piano, the venerable and much-maligned Chappell may have finally found its true calling.

For the repair process by Zhivko Girginov, click here.

Emeritus Professor Bernard T.G. Tan is a retired professor in physics from the National University of Singapore who also dabbles in music. Some of his compositions have been performed by the Singapore Symphony Orchestra.

Emeritus Professor Bernard T.G. Tan is a retired professor in physics from the National University of Singapore who also dabbles in music. Some of his compositions have been performed by the Singapore Symphony Orchestra.Notes

-

“France’s Day Fete,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 19 July 1918, 10; “Poppy Day Dance,” Malaya Tribune, 15 November 1929, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Municipal Action,” Malaya Tribune, 9 September 1930, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Moiseiwitch Says Farewell,” Straits Budget, 6 July 1933, 6. (From NewsppaerSG) ↩

-

“Children Give Concert,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 3 November 1934, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“1949 Was Successful Year for Victoria Hall,” Singapore Standard, 2 September 1950, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Grand Old Piano,” Straits Times, 30 October 1950, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Grand Old Piano.” ↩

-

“$17,000 Piano Due Soon,” Straits Times, 16 November 1951, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Anacrusis”, “The Grand Piano Mystery,” Singapore Standard, 19 February 1952, 10. (From NewspapaperSG) ↩

-

“Anacrusis”, “The Grand Piano Mystery.” ↩

-

“Anacrusis”, “The Grand Piano Mystery.” ↩

-

“Singapore Orders a New Grand Piano,” Straits Times, 28 January 1952, p. 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Anacrusis”, “The Grand Piano Mystery.” ↩

-

“Lofthouse Christens City Piano,” Singapore Standard, 13 September 1952, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Five-star Concert for Schools,” Straits Times, 18 September 1952, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

L.I.C., “Anaemic Tinklings on Our Piano,” Straits Times, 24 January 1953, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

L.I.C., “Anaemic Tinklings on Our Piano.” ↩

-

B.C., “Kentner is Pianist on Grand Scale,” Straits Budget, 16 April 1953, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Mr. R. Will ‘Eat That Piano’,” Straits Times, 16 April 1953, p. 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Kentner Tries the Piano… and It’s As Good As It Could Be,” Straits Times, 17 April 1953, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Kentner Tries the Piano… and It’s As Good As It Could Be.” ↩

-

“Chappell vs Steinway Controversy,” Singapore Standard, 18 April 1953, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Solomon Thrills Packed Hall,” Singapore Standard, 30 November 1953, 3; “Piano Recital,” Straits Times, 28 November 1954, p. 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Katchen on the Air Tonight,” Straits Times, 16 January 1955, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“A Singapore Surprise for Mr Katchen,” Straits Times, 12 January 1955, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tinny Treble, “Monument to a Blunder,” Straits Times, 21 January 1955, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Katchen Recital in Singapore,” Straits Times, 13 July 1957, 4, (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

V.F.D., “Shanghai Pianist in an Impressive Appassionata,” Singapore Standard, 9 January 1951, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Piano? More Like a Frying Pan Says Arrau,” Straits Times, 20 November 1956, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Yoko Happy With New Piano,” Straits Times, 23 November 1956, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“That Piano Finds a Friend of Truly Great Ability At Last,” Straits Times, 4 January 1957, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“That ‘Frying Pan of a Piano’ Is on Way Out,” Straits Times, 31 January 1957, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

S.B., “It Was a Privilege, Miss Kohler…,” Straits Times, 28 March 1957, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“$18,000 Piano for Theatre,” Singapore Standard, 7 January 1958, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

D.C.B., “A Great Romantic Piano Recital,” Straits Times, 1 June 1958, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Bukit Merah Public Library reopened as library@harbourfront in VivoCity in 2019. ↩