Going Against the (Rice) Grain: The “Eat More Wheat” Campaign

The call for Singaporeans to switch from eating rice to eating wheat in 1967 did not take root despite best efforts by the government.

By Jacqueline Lee

Walk into any suburban shopping mall in Singapore today and you’ll find burger joints, a pizza restaurant or two, shops selling wraps and sandwiches, and numerous Japanese restaurants specialising in udon or ramen. These places are invariably full during lunch or dinner time, a testimony to their popularity with regular folks.

However, it’s only been relatively recently that people here have gotten used to eating these foods. A little over 50 years ago, few people would be seen wolfing down a juicy cheeseburger or a tuna mayo sandwich for lunch. Slurping down a bowl of ramen, twirling al dente spaghetti around a fork or holding up a pizza slice would have been viewed as exotic and alien. Back then, most people were used to eating their lunch and dinner with rice. An effort by the Singapore government to get people to consume more of their daily dose of carbs from wheat rather than rice flopped because people vastly preferred eating white rice over bread or wheat-based noodles.

The “Eat More Wheat” campaign began in 1967 during a time when there was a global rice shortage. The campaign promoted wheat products in place of rice in the daily diet of Singaporeans.1 However, many people found it difficult to make the switch. As a reporter with the Eastern Sun newspaper noted, rice-eating was a “centuries old habit” and “we have been rice eaters since as far back as we can remember”.2

Despite a big push by the government, and support from organisations such as the National Trades Union Congress (NTUC) and Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce, the “Eat More Wheat” campaign was, by most accounts, unsuccessful, and eventually fizzled out by around 1970.3

Germination of the Campaign

In the mid-1960s, worldwide rice production dipped at the same time when demand was surging, which led to rice shortages and price increases. The price of rice rose sharply, from 35 cents per kati (about 600g) in early 1966 to around 49 cents to 51 cents per kati in 1967. During the same period though, the price of flour remained constant at 25 cents per kati.4

The price increase had a significant impact on the state’s finances. The government calculated that if people ate more wheat in place of rice, it would be able to save on “foreign exchange”. Speaking in Parliament, Finance Minister Goh Keng Swee noted that Singaporeans consumed around 4,000 tons of wheat compared to 12,000 tons of rice monthly. If they ate 4,000 more tons of locally milled wheat instead of imported rice every month, Singapore “could save $22 million in foreign exchange per year”.5

The seeds of the campaign were sown in June 1967 when Deputy Prime Minister Toh Chin Chye urged Singaporeans to change their eating habits by consuming more wheat products instead of rice due to the global rice shortage.6 A few days later, the NTUC pledged support for an “eat more wheat and less rice” campaign. “Wheat is more nutritious than rice and only at half the price,” said Seah Mui Kok, secretary-general of the NTUC.7

The Singapore Medical Association agreed that wheat was a superior alternative to rice. “A man eating six slices of bread a day obtains in his way a quarter of his daily requirements of proteins. Wheat also contains twice the amount of calcium present in rice and appreciably more iron and the water-soluble B vitamins,” explained W.O. Phoon, secretary of the association.8

Kitchens in government institutions like prisons, hospitals and welfare homes began substituting some of the weekly rice meals with wheat products. Interestingly, in addition to items like bread and noodles, the government began trying out an Australian product called Rycena, which supposedly “looks, cooks, and eats like rice”.9 Rycena’s main draw was that it could be cooked and prepared like rice, as it was a wheat derivative that would separate into soft grains.10

Rycena was introduced at the Singapore General Hospital in September and October 1967 and in several welfare homes in January 1968. The staff found that Rycena was not suitable as a rice substitute as its flavour was “akin to barley” and in the end, it was not adopted for use in government institutions.11

Using more wheat in prisons and welfare homes would not make much of a dent in rice imports though. To achieve its goal, the government would have to get Singapore’s population to change their diets. To do this, the government began the large-scale promotion of wheat products through radio and TV advertisements.

Publicity and Promotion

The message to the public – targeted mainly at housewives as most people ate at home – was that wheat was a better choice than rice due to its nutritional benefits and lower cost. The public promotion comprised exhibitions, cooking competitions and pop-up booths at events.

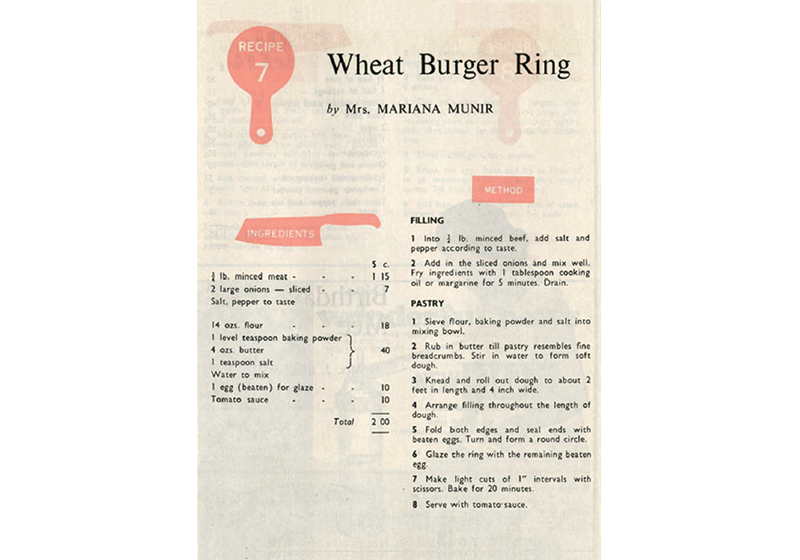

Among the biggest events were two nationwide wheat cooking competitions organised by Radio and Television Singapura, which attracted more than 2,000 participants. The competitions encouraged contestants to submit quick and economical recipes (with ingredients costing no more than $3 for the first competition and $2 for the second) using wheat flour as the main ingredient for breakfast, lunch and dinner. The recipes could be for Chinese, Malay, Indian or Western cuisine.12

For the finals of the first competition held at the Singapore Conference Hall on 17 October 1967, 10 contestants were chosen from each category and made to cook their dishes for the judges who would then determine the winners. The first prize winners were domestic science teacher Mrs Theresa Teow for Malayan savoury pancakes (Malay), Mr G.P. Ponnusamy, a cook, for wheat uppumaa (Indian), Mrs Rita Fernando, also a domestic science teacher, for stuffed fried dough balls (Chinese) and housewife Mrs Clara Anciano for basic hot cakes (Western).13

The finals of the second competition took place at the Singapore Badminton Hall on 25 February 1968.14 When interviewed for a radio programme, first prize winner of the Malay section Fatimah Wahab, a pre-university student, said: “Cooking is my favourite so after following last year’s cooking competition, I decided to participate in this year’s.” The reporter who tasted her roti udang described it as “nice, rich, golden brown” and “delicious”.15

The first prize winner of the Western section was domestic science teacher Mary Robinson, co-author of two textbooks on cooking and a dietician who relocated to Singapore more than a decade earlier. Her chilli pizza dish cost $1.68 to feed five to six people and was described as very economical. Interestingly, she noted that the eating habits of Singaporeans had changed during the time she had been in Singapore. “When I first came, when I asked a class who would eat cheese, maybe one girl would like it. Now when I ask the same question, usually I would find that the whole class, 20 girls, say, oh yes, they eat and like it, and eat it regularly. So you see, in 15 years there’s been a tremendous change in that one aspect.”16

Subsequently, 120 winning entries from the two cooking competitions were compiled into a cookbook titled “The Proof Is in the Eating” Recipe Book, which was sold to the public at $1.17 The recipes were printed in English, Chinese, Malay and Tamil.

There were also cooking competitions in schools organised by the Ministry of Education,18 a wheat food exhibition by the Siglap Women’s Association,19 an “Eat More Flour” week by the Singapore Food Manufacturers’ Association,20 a cake-making competition and exhibition by the People’s Association,21 and a Christmas Fair where wheat products were sold.22

At the wheat food exhibition, an array of Chinese, Indian, Pakistani and European dishes made from wheat flour and other ingredients were on display and for tasting. Speaking at its opening in August 1967, Culture and Social Affairs Minister Othman Wok stressed that the worldwide shortage of rice was not the only reason the government was encouraging the switch to wheat. “It is common knowledge that wheat and wheat products are more health-giving than rice, although not all realise that wheat and wheat products are also cheaper than rice,” he said.23

Three men literally “took the cake” at the cake-making competition on 30 March 1969 and swept the top three prizes. Petty Officer Chang Heng Wan, who won the first prize, had worked as a cook in the Admiralty House at the Naval Base for 19 years.24 (Sadly, the newspaper report did not mention the type of cake he had baked.)

The “Eat More Wheat” campaign included a partnership with two local flour mills – Prima Limited and Khong Guan Flour Milling Limited – which footed the bill for the radio and TV advertisements.25 These advertisements focused on the versatility of wheat flour that could be used to make “the right food at any time for any occasion” and “healthy food good for young and old alike”.26

The media also threw in their support. Marianne Pereira of the Eastern Sun hatched a cunning plan for a housewife to get her husband and family interested in wheat-based meals. “It is up to us women to see that more wheat is eaten,” she wrote. “At the dining table serve your husband with rice but serve yourself with something out of wheat and eat it with smacking relish. Curiosity it is said is the start of all adventure. And your husband’s curiosity will lead him to ask, ‘What is that, can I have some?’”27 According to Pereira, this was likely to lead to the husband asking for that dish the next night.

She said women should also highlight the advantages of eating wheat. “Subtly also point out that wheat is more economical than rice. Point out to the family paunches (subtly too) and announce that wheat is slimming. Point out that wheat is beneficial to health.”28

The Campaign Fizzles Out

Unfortunately, despite these efforts, the campaign appeared to make little headway. The Straits Times described the campaign as “a direct assault on basic habits” that would “almost certainly fail while a more subtle approach would well speed up the trend to flour which is already noticeably under way”, adding that “people to whom ‘rice’ and ‘food’ are synonymous will not be easily persuaded to abandon ‘rice’”.29

The paper questioned if wheat was truly cheaper than rice, as wheat products were less palatable and had to be supplemented with other ingredients. Furthermore, the paper noted, wheat products required more time and preparation than rice, which could simply be boiled.30

Members of the public interviewed in March 1968 by Radio Singapura expressed difficulty in substituting rice for wheat. A man said: “It’s just like asking us to give up smoking. It just isn’t possible.” Another man said: “In preparing wheat for food, it will take the housewife a much longer time. And in rice, it has been the eating of the people for generations. So as to say that wheat can take the position of rice, I am quite doubtful unless the eating habit of the people can change, which I do agree, but it will take time.”31

The Singapore Medical Association criticised the government for not involving doctors who could have helped explain why wheat was better for health. “The campaign would have been a greater success if the medical profession had been alerted to the need for their participation,” said the association. “It is impossible to expect a few jingles over the air with one’s morning coffee to bring about a social revolution in the eating habits of the majority of the people in Singapore.”32

In Parliament in December 1967, Member of Parliament for Aljunied S.V. Lingam questioned the campaign’s target audience. “To whom are we to beam this campaign to? To the rich or to the poor?” he demanded to know. “[T]he campaign seems to me to be directed at the rich who ironically are already consumers of wheat and who could afford to pay for rice at ten times its present price.”33

He said the campaign was misguided in telling poor people to save money by eating wheat, as they would spend more money on meat, eggs and supplementary ingredients. He also commented that the cooking competition’s limit of $3 of ingredients for one meal was too generous, as poor families budgeted $3 for an entire day of meals. “Does the Minister [of State for Culture Lee Khoon Choy] sincerely believe that the poor can afford this?” he asked.34

Straits Budget reporter Henry L. Pau described the campaign as “pretty futile”. “The wheat foods advocated are neither new nor particularly cheap, and the people are already eating as much of them as they can afford or can stomach.” He added that it was “more costly to the housewife – 48 cents a kati of rice, 80 cents the equivalent quantity of bread”.35

Rice Reigns

In 1968, a survey on the wheat-eating habits of Singaporeans found that “rice eaters won’t desert the bowl”. Of the 900 Chinese, Malay and Indian households interviewed, only 16 households had started consuming wheat during the past six months of the campaign. Less than 2 percent of those surveyed had heeded the call. “This rate of switching appears to be low considering the heavy publicity campaign to eat more wheat products,” noted the report. According to the survey, the food consumed for breakfast and tea had a satisfactory amount of wheat, while lunch and dinner meals did not see an increase in wheat products. To get a third of the population consuming a wheat-based meal for lunch and dinner in 10 years would require a much higher increase in the rate of change.36

By the early 1970s, the “Eat More Wheat” campaign dropped off the radar. In response to a letter to the Straits Times in August 1971 asking what had happened to the campaign, the Health Ministry said that there was no longer a need for the campaign because of the green revolution and the consequent increase in rice yields.37 As rice production increased, rice prices dropped and matched the price of wheat.

Even though the campaign failed to change diets in the three years or so that it ran, in the subsequent decades, the habits and tastebuds of Singaporeans did indeed change. Today, although rice has not been dethroned, people eat wheat-based foods regularly, whether in the shape of a hamburger, a bowl of instant noodles, a plate of pasta or a slice of pizza.

During the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, the shortage of flour was certainly felt as evidenced by the queues at baking supply shops. The subsequent pandemic baking trend for making sourdough bread also had its adherents here as well. Thanks to the forces of globalisation, while rice is still nice in Singapore, wheat is definitely also neat.

Jacqueline Lee is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, and works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia collections. Her responsibilities include developing and promoting the Legal Deposit and Web Archive Singapore collections.

Jacqueline Lee is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, and works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia collections. Her responsibilities include developing and promoting the Legal Deposit and Web Archive Singapore collections.NOTES

-

“Minister: Wheat Diet Doubly Advantageous,” Eastern Sun, 13 August 1967, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Marianne Pereira, “The Best Thing About Wheat Is Variety,” Eastern Sun, 20 August 1967, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“NTUC Pledges Full Support To ‘Eat More Wheat’ Campaign,” Eastern Sun, 27 June 1967, 2; Chinese Chamber Backs ‘Eat More Wheat Campaign’,” Eastern Sun, 29 August 1967, 10; “P.S.A’s Eat More Wheat Campaign,” Eastern Sun, 27 September 1967, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“How To Save $22m – By Dr. Goh,” Straits Budget, 13 September 1967, 19. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Eat Less Rice, More Flour, Urges Dr. Toh,” Straits Budget, 5 July 1967, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“NTUC Pledges Full Support To ‘Eat More Wheat’ Campaign”; “Start ‘Eat Less Rice’ Campaign Plea by NTUC,” Straits Budget, 5 July 1967, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Medics in Full Support of Eating More Wheat,” Eastern Sun, 1 November 1967, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ministry of Social Affairs, “Eat More Wheat Campaign,” 1967–1971, government record, 100, 152, 166. (From National Archives of Singapore, microfilm no. MSA 2353) ↩

-

Ministry of Social Affairs, “Eat More Wheat Campaign,” 145. ↩

-

Ministry of Social Affairs, “Eat More Wheat Campaign,” 145. ↩

-

“Cooking With Wheat: Radio, TV Contest for Housewives,” Straits Times, 24 August 1967, 6; “Dy P.M. Happy Over Eat More Wheat Drive,” Eastern Sun, 18 October 1967, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Wheat Flour Dishes: The Winners,” Straits Times, 18 October 1967, 4. (From NewspaperSG); RTS Enterprises (Singapore), “The Proof Is in the Eating” Recipe Book (Singapore: Printed by the Govt. Print. Off., 1969), 31, 139, 163, 171. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 641.6311 RTS) ↩

-

“Cooking Contest: 900 Wheat Recipes Received,” Eastern Sun, 6 February 1968, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Radio Singapura, “Background No. 1: Why Wheat,” 29 March 1968, sound, 14:40, 14:49. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 1998006042) ↩

-

Radio Singapura, “Background No. 1: Why Wheat,” 18:45. ↩

-

RTS Enterprises (Singapore), “The Proof Is in the Eating” Recipe Book. ↩

-

“Cookery Contest ‘A Gourmet’s Delight’,” Straits Times, 6 August 1968, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Exhibition of Wheat Food Dishes,” Eastern Sun, 27 July 1967, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“‘Eat More Flour Week’ in S’pore Next Month,” Straits Budget, 30 August 1967, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“PA to Hold Cake-making Exhibition,” Eastern Sun, 23 February 1969, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Spend Old Notes for Full Value at Xmas Fair,” Eastern Sun, 30 November 1967, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Exhibition of Wheat Food Dishes”; “Minister: Wheat Diet Doubly Advantageous,” Eastern Sun, 13 August 1967, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Wee Choo Kim, “Petty Officer Chang Takes the Cake,” Straits Times, 30 March 1969, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ministry of Culture, “Eat More Wheat Campaign,” 82. ↩

-

“Page 3 Advertisements Column 1,” Eastern Sun, 24 October 1967, 3; “Page 5 Advertisements Column 1,” Eastern Sun, 29 November 1967, 5; “Page 5 Advertisements Column 1,” Eastern Sun, 23 November 1967, 5; “Page 3 Advertisements Column 1,” Eastern Sun, 17 November 1967, 3; “Page 5 Advertisements Column 2,” Eastern Sun, 11 November 1967, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Pereira, “The Best Thing About Wheat Is Variety.” ↩

-

Pereira, “The Best Thing About Wheat Is Variety.” ↩

-

“Flour v. Rice,” Straits Times, 9 September 1967, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Flour v. Rice.” ↩

-

Radio Singapura, “Background No. 1: Why Wheat,” 29 March 1968, sound, 5:33, 7:17. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 1998006042) ↩

-

“Doctors to S’pore Govt: Why Not Seek Our Help?,” Straits Budget, 27 November 1968, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“‘Eat More Wheat’ Campaign Criticised,” Eastern Sun, 20 December 1967, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Henry L. Pau, “Eating More Wheat But Cheaply,” Straits Budget, 24 January 1968, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Rice Eaters Won’t Desert the Bowl, Says a Wheat Survey,” Straits Times, 29 August 1968, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

An Arian, “We’ve Got to Keep All the Campaigns Going,” Straits Times, 20 August 1971, 23; “Keep Clean Drive Still On – Ministry,” Straits Times, 21 August 1971, 5. (From NewspaperSG). [Note: The “green revolution” in Asia refers to the cultivation of high-yield rice varieties and the adoption of agricultural processes like chemical fertilisers and mechanisation.] ↩