The Early History of Printing in Singapore

Printing in Singapore dates back 200 years with the establishment of a press by Christian missionaries. Their efforts to spread the gospel also helped bring the technology here.

By Gracie Lee

The history of printing in Singapore shares similarities with that of many Southeast Asian countries. Christian missionaries were responsible for introducing the technology to the region, with the aim of spreading the gospel in the local languages. However, the presses were not limited to religious literature and were also used for government and commercial purposes. Over time, the technology and expertise required to operate these presses grew, leading to the emergence of secular printing operations.

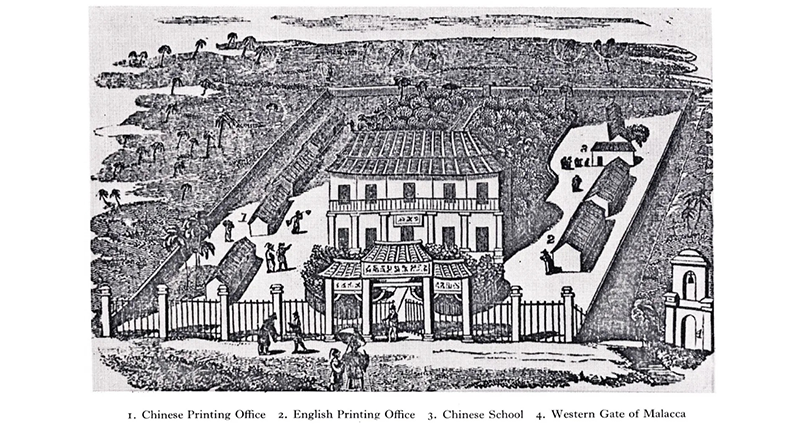

In Singapore, the start of printing can be traced to the establishment of Mission Press by the London Missionary Society (LMS). The London Missionary Society, which is now part of the Council for World Missions, was a non-denominational Protestant organisation founded in England in 1795. One of its chief aims was to reach out to China’s vast population but initial attempts failed due to the Qing government’s regulations that forbade open preaching and the publication of foreign literature as measures to deter Western influence. While waiting for Chinese restrictions to loosen, Robert Morrison, the society’s first missionary to China, and his co-worker William Milne decided to set up a temporary mission somewhere else, a place where they could learn Chinese and evangelise more freely. They settled on Malacca because of its central location and sizeable Chinese population.

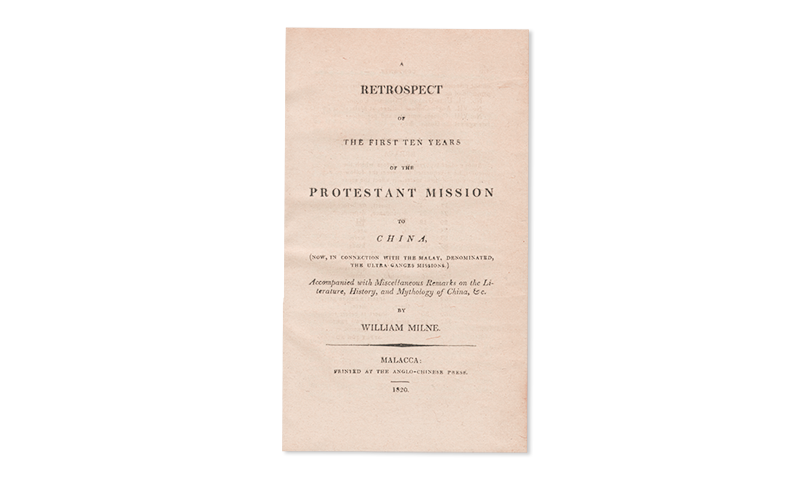

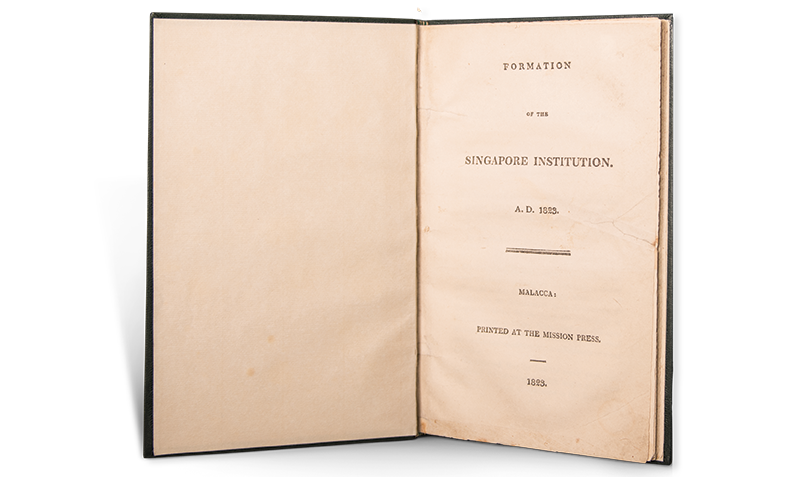

In 1815, Milne arrived in Malacca with Liang A-Fa, one of their first Chinese converts and a printer trained in xylography (woodblock printing), sowing the seeds for a new mission base that would include a school and a printing press. The output of the printing office was prodigious, and they produced a variety of religious and secular works in Chinese, English and Malay. Some of its notable publications include Stamford Raffles’s Formation of the Singapore Institution, A.D. 1823 (1823) where he outlined his proposal for an educational institution in Singapore, known today as the Raffles Institution. The Malacca station also served the printing needs of the government and merchants of Singapore up until the early 1820s.1

The First Printing Press in Singapore

The developments in Malacca laid the groundwork for the society’s expansion into Singapore. In October 1819, Samuel Milton, who arrived in Malacca in 1818 to work with the Chinese community there, became the first LMS missionary appointed to Singapore. He was joined in May 1822 by Claudius Henry Thomsen, a Danish missionary versed in the Malay language and printing in Malay. When Thomsen departed Malacca for Singapore, he brought with him a small portable press.

Most historians regard this as Singapore’s first printing press. Thomsen also brought along with him two unnamed assistants who had been helping him at the Malay and English printing press in Malacca. Although their identities are not known, they were likely Abdullah Abdul Kadir (better known as Munshi Abdullah) – who had worked alongside Thomsen at the Malacca mission as a Malay teacher, translator, transcriber, compositor, printer and typecutter – and a Eurasian printer named Michael.2

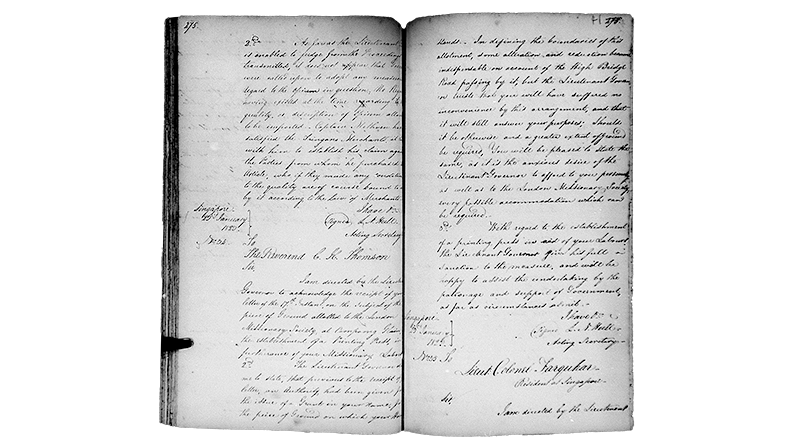

Although there is a wealth of research on the history of printing in Singapore, the exact date when printing was first introduced here remains unknown. What is certain is that Stamford Raffles officially granted Thomsen permission to operate a printing press in Singapore on 23 January 1823. Six days earlier, on 17 January, Thomsen had submitted a request “to use a printing Press with which I may be able more effectively to pursue my labours as a Christian missionary among the Malays”. L.N. Hull, acting secretary to the Lieutenant-Governor, replied that Raffles “gives his full sanction to the measure, and will be happy to assist the undertaking by the patronage and support of government as far as circumstances permit”.3

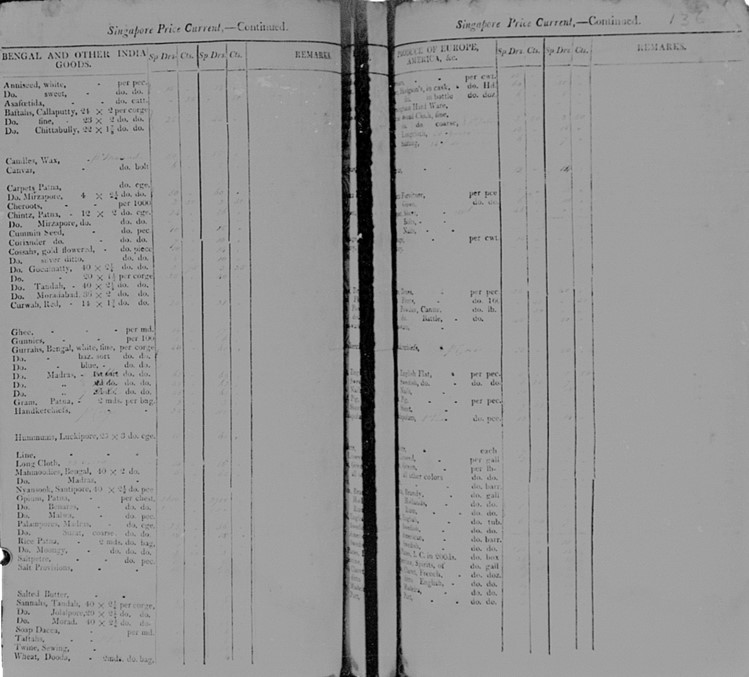

While formal approval was only given in January 1823, there is evidence that some form of printing had already taken place before that. Among the earliest dates proposed is May 1822. In Cecil K. Byrd’s 1970 study on early printing in the Straits Settlements, he included an illustrated plate on what he believed is the earliest extant sample of printing in Singapore.

The document, titled “Price Current of Goods at Singapore”, comprises four pages printed on paper watermarked “1819”. It presents a list of commodities categorised under headings such as “Eastern Produce”, “China Goods”, “Bengal and other Indian Goods” and “Produce of Europe, America &c”. The cover sheet bears a handwritten date of 31 May 1822. Byrd observed that the printing was coarse, suggesting that this might be a small government job that was produced on the portable press that Thomsen had brought over from Malacca.4

Further evidence of pre-1823 printing in Singapore is supported by a study that references a letter written by Milton to the LMS in September 1822. In the letter, Milton mentions having printed two works in Chinese. He wrote: “I have employed two Chinese type-cutters to carry on a periodical work in Chinese and also to print an Exposition of the Book of Genesis in that language. Three men are cutting Siamese types for printing a pamphlet on the redemption of sinners by Jesus Christ…” However, as no further mention was made of these two Chinese works, it remains doubtful if the printing was ever completed.5

Some historians have also suggested that Thomsen and Munshi Abdullah were involved in printing some legislations for Raffles in the months leading up to 1 January 1823.6 In Munshi Abdullah’s autobiography Hikayat Abdullah (Stories of Abdullah), he recounts an urgent printing job that he undertook for Raffles:

The settlement of Singapore had become densely populated and Mr. Raffles drafted laws clarifying the regulations and the procedure for their enforcement which were needed in the Settlement to protect its inhabitants from danger and crime. He drew up several sections in English dealing with penalties for infringing the regulations, which were then translated into Malay. After this he told Mr. Thomsen to print them. Now at that time there were not enough types in Malacca, so he told me to make up the deficiency. For two days I sat making types. Then they were ready, and the printing was done, fifty copies in Malay and fifty copies in English. A friend of mine set up the type, a young Eurasian name Michael. At last at three o’clock in the morning all was finished, for the same morning, which was the first day of the new year, they wanted to publish the laws. Eyes drooped and stomachs felt the pangs of hunger, all because the task had to be finished that night. For Mr. Raffles had insisted that it be ready by the next morning. And the next morning the notices were posted in every quarter of the town.7

Raffles was a passionate advocate for printing and played a key role in introducing the first printing press to Bencoolen (now known as Bengkulu) during his tenure as lieutenant-governor there. On his return to Singapore in October 1822, Raffles asked Milton if the mission had a printing press as he wanted to “print several things”. On learning that there was none, Raffles urged Milton to procure some for the LMS.8

In December 1822, Milton sailed for Calcutta to obtain the much-needed presses, armed with three letters of introduction from Raffles. While he was away, Raffles allowed Thomsen to operate a printing press. Thomsen took the opportunity to update the LMS on the activities of the mission in Singapore and to appeal for new presses.

On 20 February 1823, Thomsen wrote that they had started printing in both English and Malay. They had a small type-foundry and were also engaged in bookbinding. However, he noted that the press was a small travelling one and they only had a limited quantity of Malay and old English type. Consequently, they were restricted in the number of pages they could print. He also cautioned that the type would be almost worn out after 12 months, and that regular book printing would have to be postponed until the LMS directors supplied their needs.9

Separately, Raffles wrote to the LMS directors to assure them that “the government will engage to do all their work at the missionary press” and that there was “reason to believe that when once it is in activity there will be various demands upon it by the community”.10

Milton returned to Singapore in April 1823 with “three printing presses and their furniture, one fount of English types, one fount of Chinese types (this is the first fount of these types that was ever cast), one fount of Malay types, with a quantity of English printing paper, printing ink, English compositor also a quantity of type metal, metal furnace and ladles, one set of Siamese, one set of Malay, one set of Arabic Matrices and everything necessary for casting types in the above mentioned languages”, as well as “a complete set of European tools, figures, letters, presses for binding books”.11

However, as the presses were procured without the knowledge of the LMS and Milton lacked the funds to pay for them, the equipment was transferred to the Singapore Institution which covered the purchase using public subscription funds. Milton remained in charge of the printing press and used it to print religious literature and Singapore’s first newspaper, the Singapore Chronicle. The first issue was published on 1 January 1824.

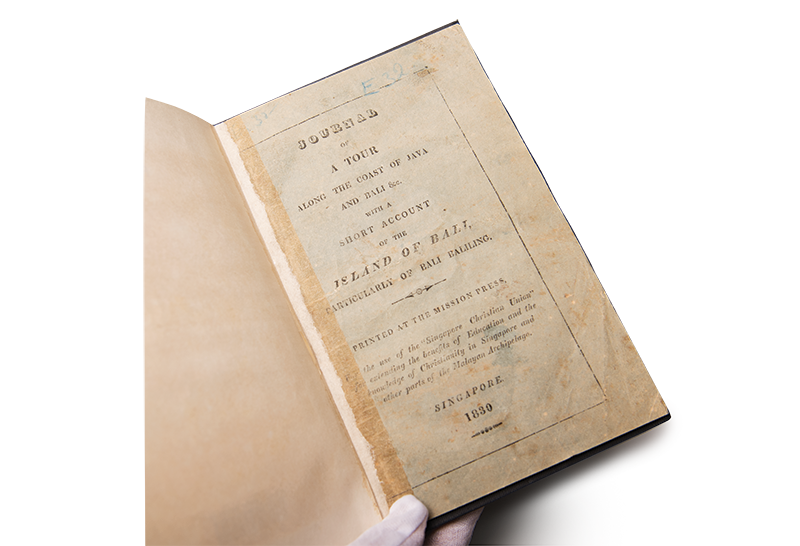

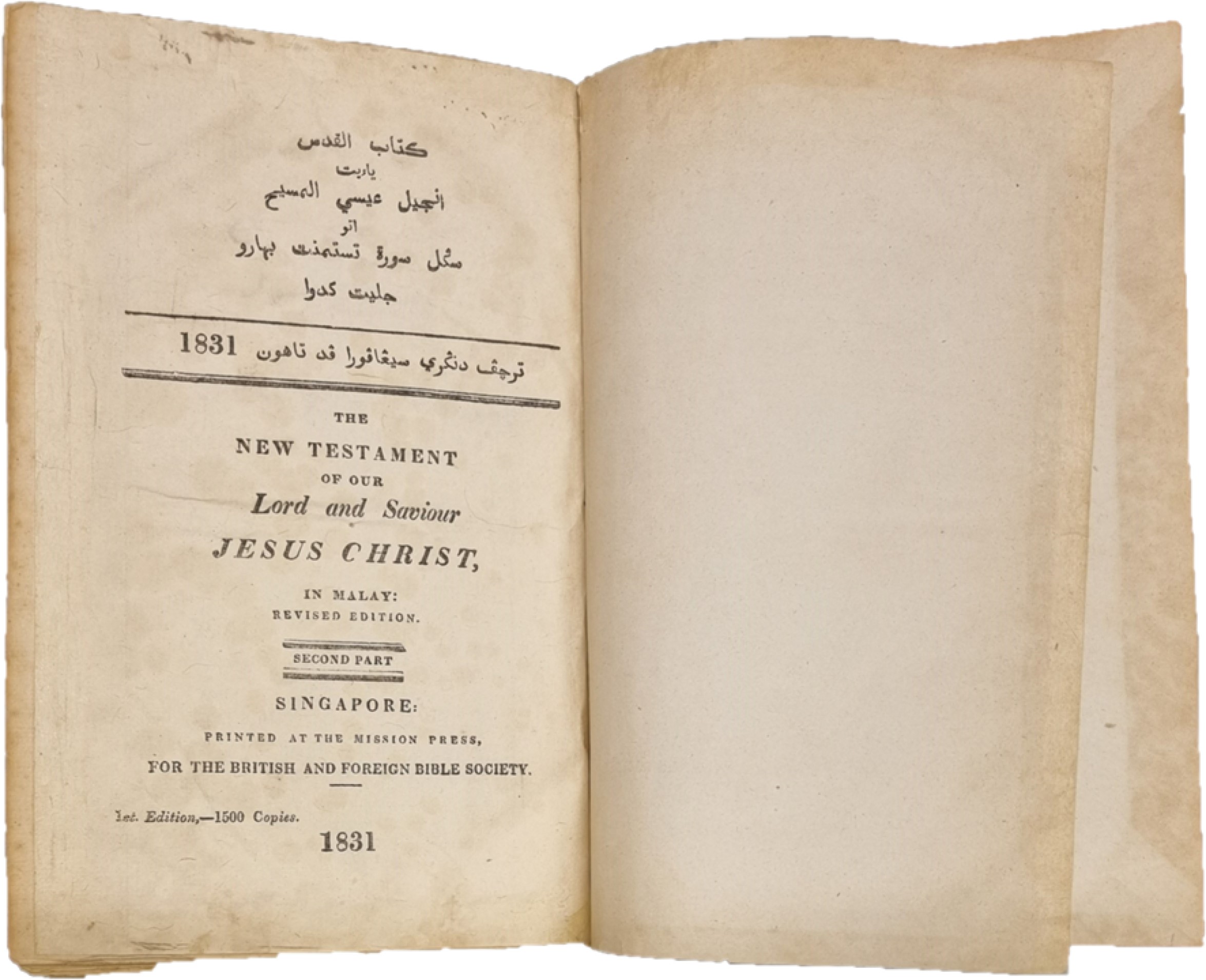

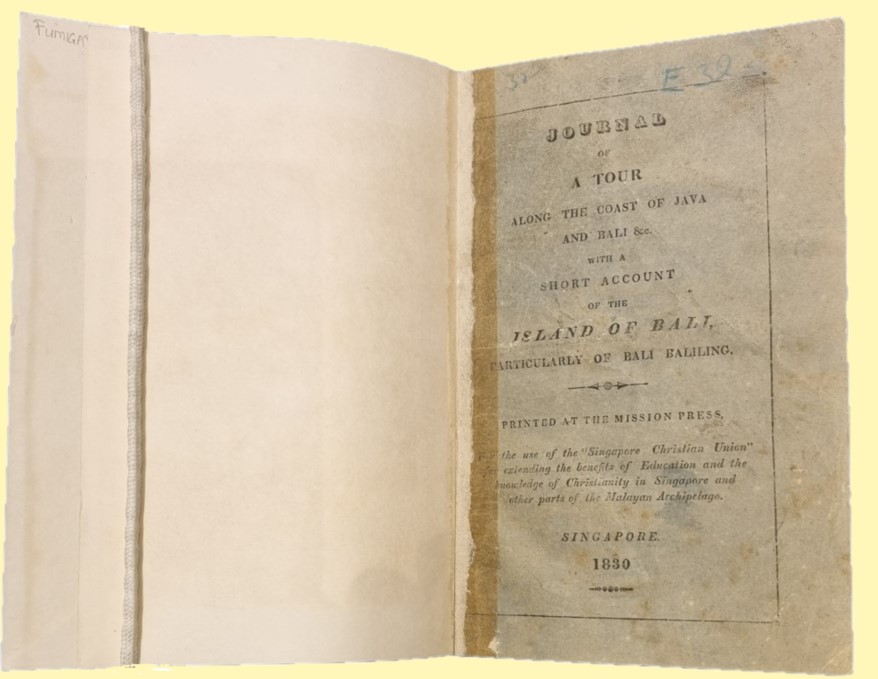

After Milton retired from the LMS in 1825, Thomsen took over the press and continued its dual function of printing religious publications as well as secular works received through government and commercial jobs.12 These include missionary Walter Henry Medhurst’s Journal of a Tour Along the Coast of Java and Bali (1830) where he recounts his travels to the two places with Reverend Jacob Tomlin in 1829,13 and Kitab Al-Kudus, Ia-itu, Injil Isa Al-Masihi Atau Segala Surat Testament Bahru (The New Testament of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ in Malay) (1831). This is a revised translation of the New Testament in Malay by Thomsen and Robert Burn, the Chaplain of the Anglican Church in Singapore.14

Printing by the American Mission

Because of his failing health, Thomsen left Singapore in 1834. However, before leaving, he made the questionable move of selling the LMS’s printing equipment and land to the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM). Uncertainty over the ownership of the property lingered until the board exited Singapore in 1843 and its assets were transferred to the LMS at no cost.15

The ABCFM had been looking for a base in Southeast Asia to print and distribute Christian literature in Chinese and the indigenous languages of Southeast Asia. Singapore was chosen because of its favourable climate, safe conditions and thriving port that saw native vessels calling from China and the region.16

Ira Tracy, the board’s first missionary to Singapore, arrived in 1834 and was joined by printer Alfred North two years later. Tracy oversaw Chinese printing while North supervised the printing, proofreading, distribution and binding of all other books.17 They were helped by Achang, the foreman for Chinese printing who was also the former assistant to Liang A-Fa.18 They also received assistance from Munshi Abdullah, who was employed as a Malay teacher and who also aided North in editing and printing Malay literature. Notably, North printed Munshi Abdullah’s Kisah Pelayaran Abdullah (The Story of Abdullah’s Voyage) in 1837, which chronicles the Munshi’s travels up the east coast of Malaya.19

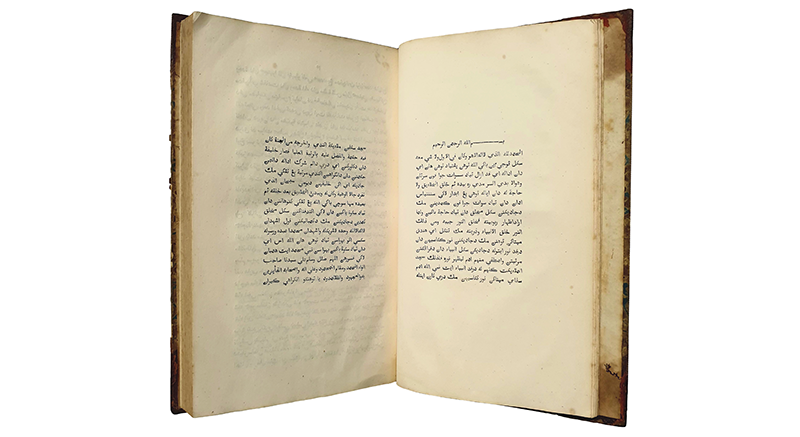

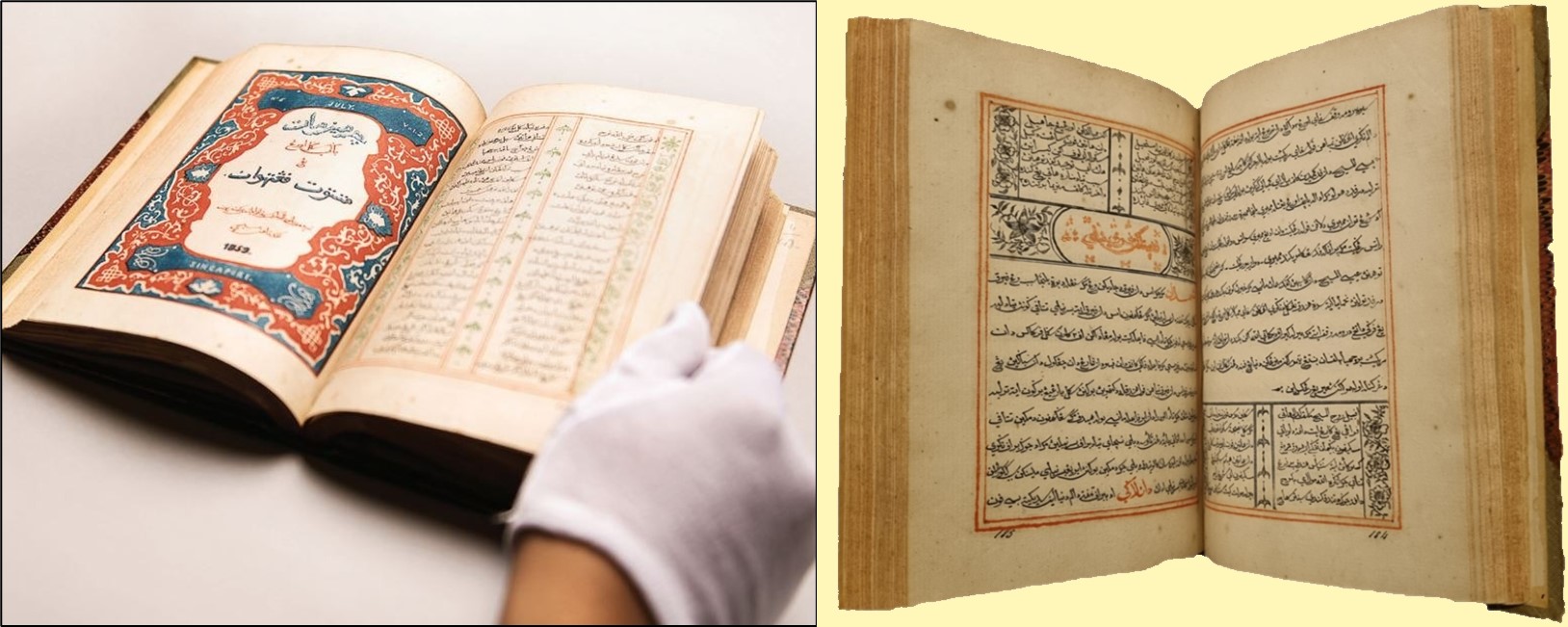

By 1841, the Mission Press of the ABCFM had printed over 14 million pages of works, with Chinese forming the bulk, and the rest in Malay, Bugis, Siamese, Japanese and English.20 One significant publication that they produced was the Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals), published in 1840. This is the first printed edition of the Sulalat al-Salatin (Genealogy of Kings). Written in Jawi and edited by Munshi Abdullah, this 17th-century court text is one of the most important sources on the history of early Singapore.21

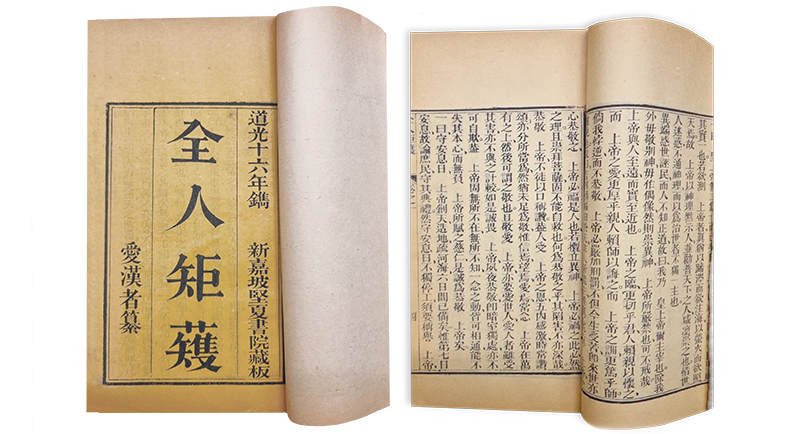

The Mission Press of the ABCFM also produced the earliest locally printed Chinese book held in the National Library’s collection: 全人矩矱 (Quan Ren Ju Yue), translated as The Perfect Man’s Model or The Complete Duty of Man. It was written by German Protestant missionary Karl Friedrich August Gützlaff under the pen name 爱汉者 (“Lover of the Chinese”) and printed in 1836 in 3,000 copies by 坚夏书院 (Jian Xia Shuyuan), the printing arm of the American mission in Singapore. The book presents Jesus as the “perfect man” through the tenets of Confucianism.22

Lithography in Malay Printing

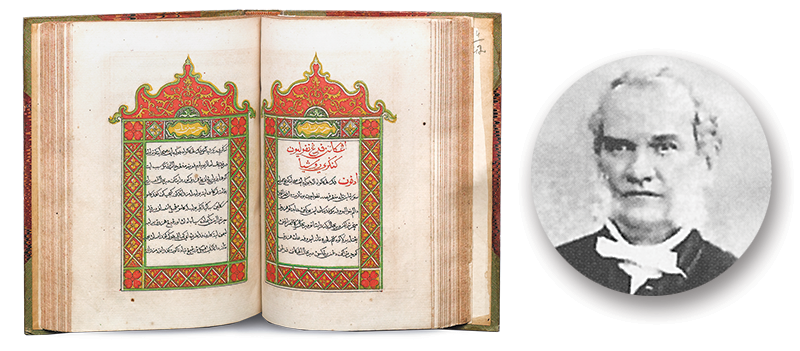

The ABCFM began winding down operations in Singapore from 1841 and completed their withdrawal by 1843.23 Meanwhile, the printing activities of the LMS, which had been at a standstill since the departure of Thomsen, was revived with the arrival of Protestant missionary Benjamin Keasberry. In 1839, Keasberry joined the local LMS mission out of a desire to evangelise to the Malay-speaking population. He set up the Malay Mission Chapel (today’s Prinsep Street Presbyterian Church) and schools, as well as published and translated many works into Malay.

Keasberry was able to make considerable headway owing to his fluency in the language and the printing skills that he had acquired from Walter Henry Medhurst in Batavia (present-day Jakarta). The students in Keasberry’s school were also taught printing as part of their vocational education and some were hired as apprentices at the Mission Press. In particular, Keasberry is known for advancing the use of lithography, the process of printing from a smooth surface, for example, a limestone slab that has been specially prepared so that ink only sticks to the design to be printed. This allowed the printing of text that resembled the flow of the handwritten script found in Malay manuscripts.

Among his finest lithographic works is the journal Cermin Mata Bagi Segala Orang Yang Menuntut Pengetahuan (Eye Glass for All Who Seek Knowledge), one of the earliest Malay periodicals published in Singapore.24 Keasberry’s success paved the way for the wide acceptance of the technology among local Malay commercial presses, as it presented a gradual transition from manuscript copying to printing that was less costly than typography.25

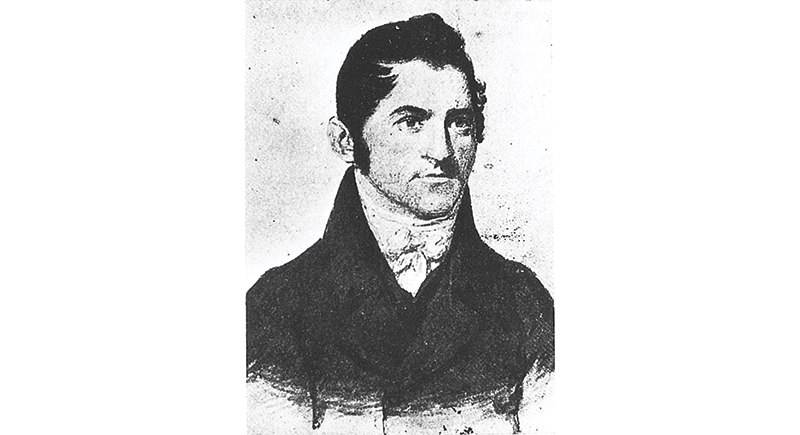

(Right) British Protestant missionary Benjamin Keasberry is known for using lithography in Malay printing that resembled the flow of the handwritten script found in Malay manuscripts. Image reproduced from Prinsep Street Presbyterian Church 1843–2013: Celebrating 170 Years of God’s Faithfulness (Singapore: Prinsep Street Presbterian Church, 2013). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. 285.25957 PRI).

Development of a Metallic Chinese Type

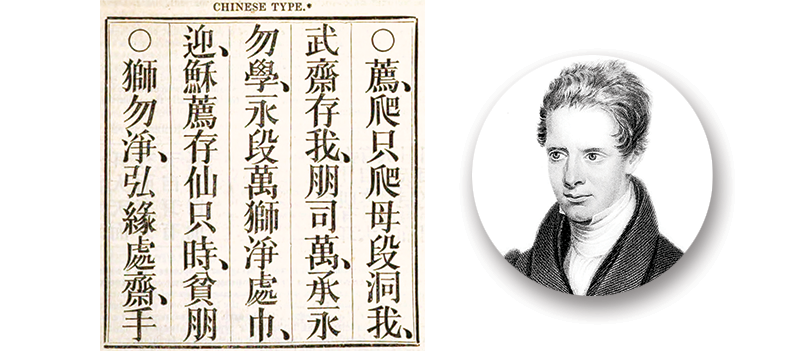

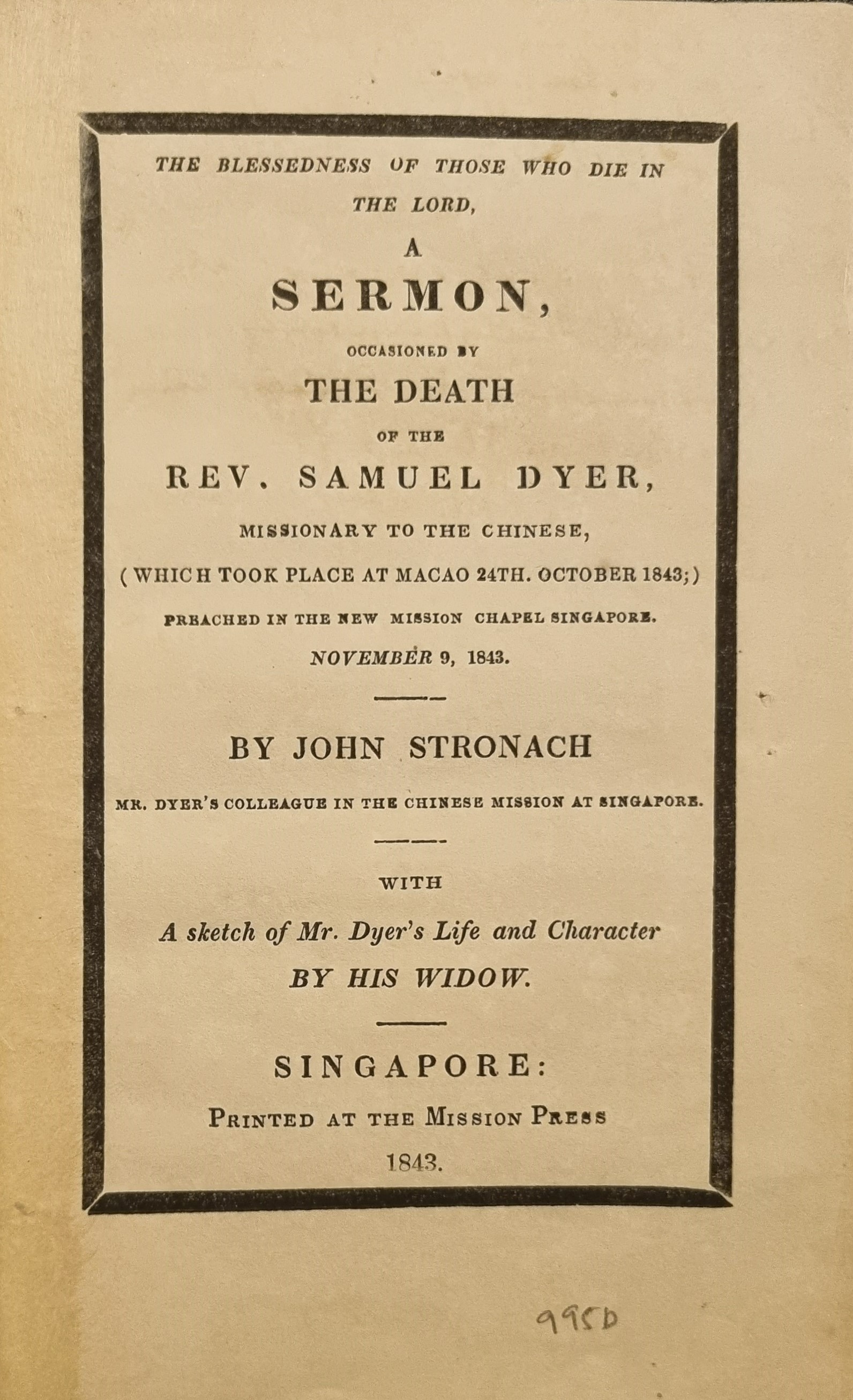

Progress was not limited to Malay printing alone. Samuel Dyer, an LMS missionary stationed in Singapore from 1842 to 1843, has been widely credited for his pioneering work on the development of a fount of movable Chinese metallic types that was accurate, aesthetically pleasing, less costly and durable.

(Right) British Protestant missionary Samuel Dyer pioneered the use of movable Chinese metallic types that were accurate, aesthetically pleasing, less costly and durable. Image reproduced from Evan Davies, The Memoir of Samuel Dyer: Sixteen Years Missionary to the Chinese (London: Snow, 1846). Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

Dyer’s movable types received high praise from missionary Walter Henry Medhurst who wrote: “The types are such as to afford entire satisfaction. The complete Chinese air they assume so as not to be distinguishable from the best style of native artists, together with the clearness and durability of the letter, would recommend them to universal adoption.”26 The types subsequently became the standard for Chinese printing in the 1850s, replacing the woodblocks that were traditionally used.27

Dyer first arrived in Penang in 1827 and stayed on as a missionary to the Chinese. Not long after, he began exploring ways to improve the process of Chinese printing. Up until then, Chinese printing was mainly carried out using the xylographic (woodblock) method. The vast number and sheer variety of characters in the Chinese corpus posed significant challenges to the development of a Chinese type. Dyer spent months studying the composition of Chinese characters and identifying commonly used ones. He experimented with stereotyping before settling on creating a movable metallic type through steel punch cutting.

Dyer continued his development work in his later postings to Malacca (1835–39) and Singapore (1842–43). At the time of his death in 1843, Dyer had completed about half of the over 3,000 characters planned for the fount. His work was continued by LMS missionary and printer Alexander Stronach, who took the foundry with him when he was transferred to Hong Kong in 1846.28

Early missionaries like Milton, Thomsen, Tracy, North, Keasberry and Dyer, and their assistants such as Munshi Abdullah, occupy an important place in the early history of printing in Singapore. They were pioneers in religious printing and also in vernacular, government and commercial printing. Their efforts paved the way for the development of European commercial printing in the 1830s, vernacular commercial printing in the 1860s and 1870s, and the establishment of the Government Printing Office around 1861.29

Singapore: Printed at the Mission Press, 1830.

Call no. RRARE 992.2 JOU; Accession no. B03013533G).

English Protestant missionary Walter Henry Medhurst of the London Missionary Society recounts his travels to Java and Bali with Reverend Jacob Tomlin in 1829. Parts of the journal have been republished many times for its rich descriptions of Bali. This is the earliest English book printed in Singapore that is found in the National Library’s collection.

Singapore: Printed at the Mission Press, 1830.

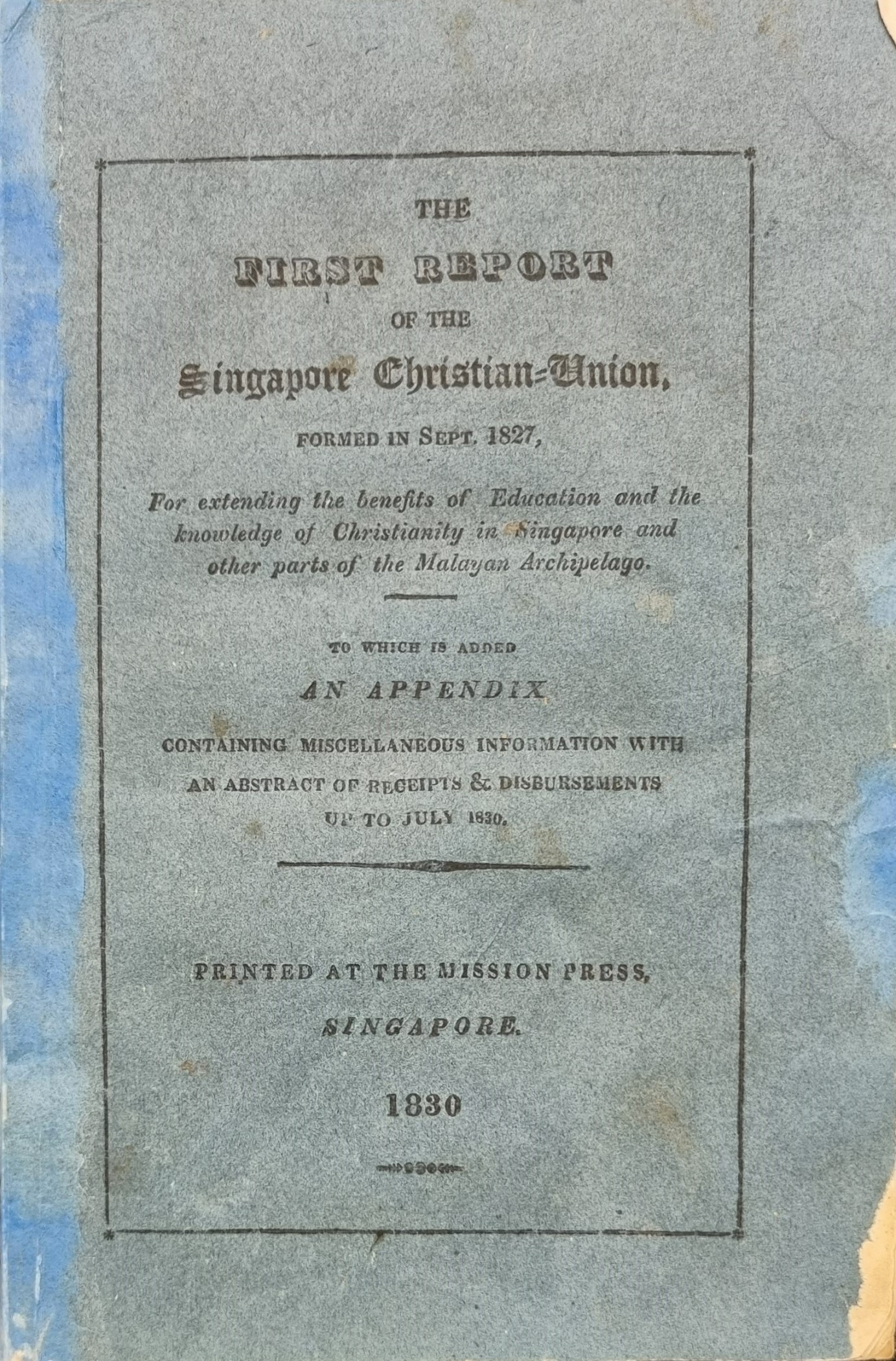

Call no. RRARE 266.759 SCURSC; Accession no. B20016993H

The Singapore Christian Union was formed in 1827 to promote literacy and spread Christianity in Singapore and the Malay Archipelago through the establishment of schools and the distribution of scriptures and tracts. This inaugural report provides an update on the progress of education and the circulation of Christian literature in Singapore and Southeast Asia.

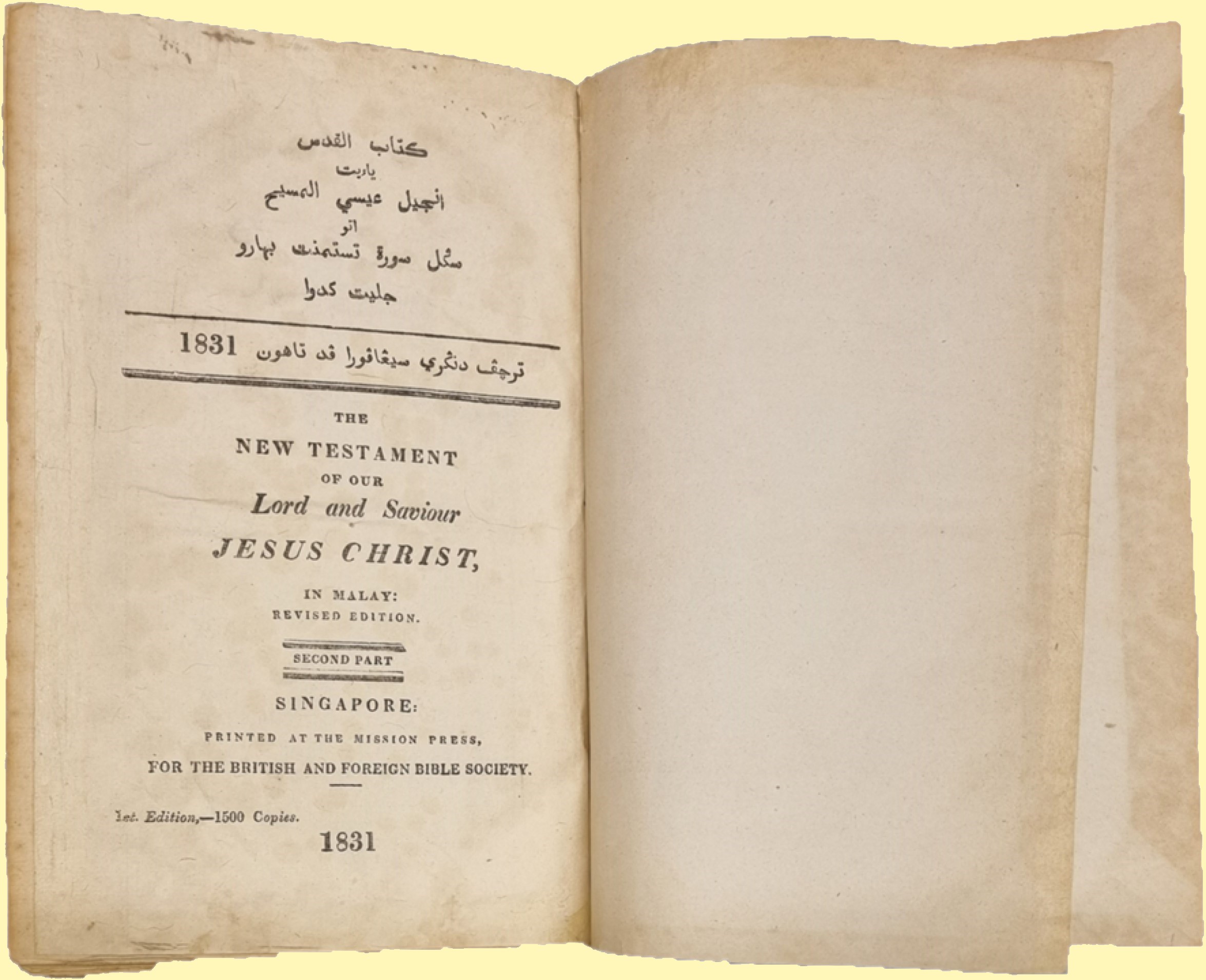

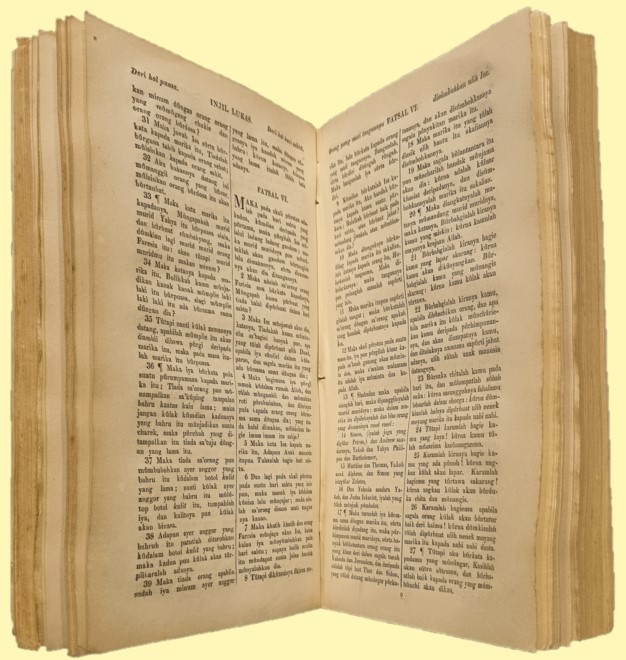

Singapore: Printed at the Mission Press for the British and Foreign Bible Society, 1831.

Call no. RRARE 225.59928 BIB; Accession no. B19016274H.

This revised translation of the New Testament in Malay was prepared by Claudius Henry Thomsen and Robert Burn, the Chaplain of the Anglican Church in Singapore. Thomsen began learning and translating the Bible into Malay with the help of Munshi Abdullah while they were in Melaka.

Singapore: Printed at the Mission Press for the British and Foreign Bible Society, 1831.

Call no. RRARE 225.59928 BIB; Accession no. B19016274H.

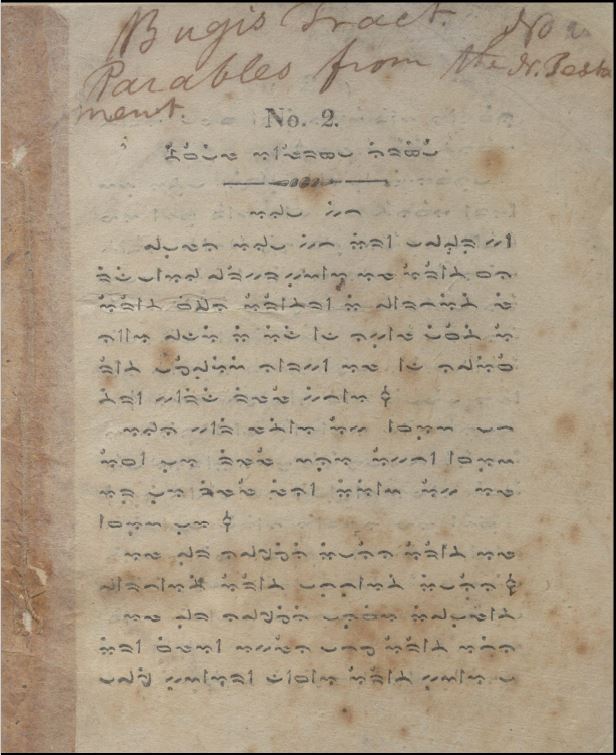

Claudius Henry Thomsen started learning the Bugis language sometime around 1824 with the intent of producing a tract to distribute to Bugis vessels that visited Singapore during the trading season. He printed 2,000 copies of a 12-page booklet on the Parables of the New Testament which was likely translated from Malay by his Bugis teacher. There appeared to be some interest in these pamphlets as they were brought back to the Celebes.

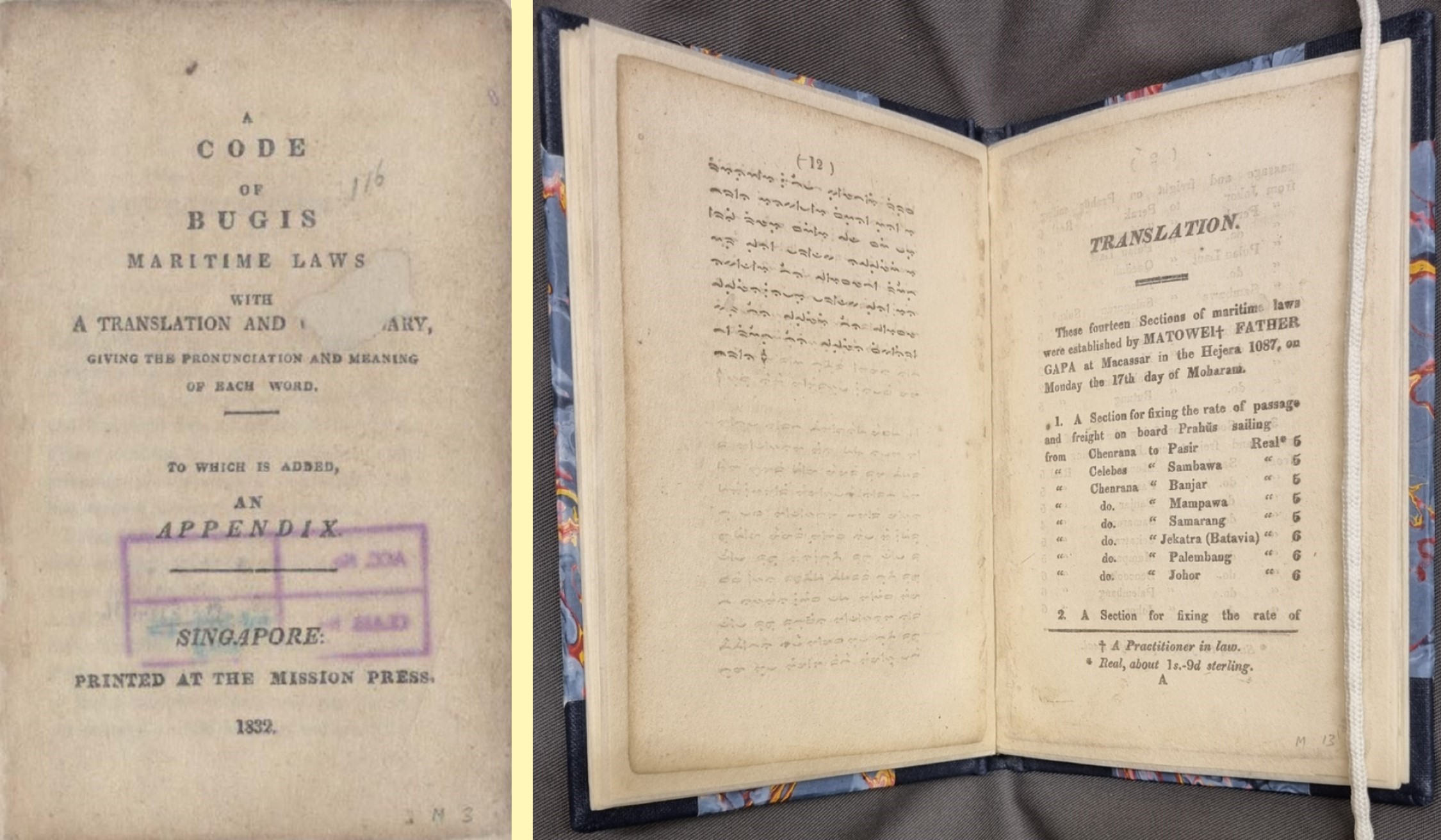

Singapore: Printed at the Mission Press, 1832.

Call no. RRARE 343.5984096 COD; Accession no. B03053896A.

This maritime code of the Bugis was translated by Claudius Henry Thomsen into English. It was printed from types that were cast in Singapore using moulds made in Serempore, in India.

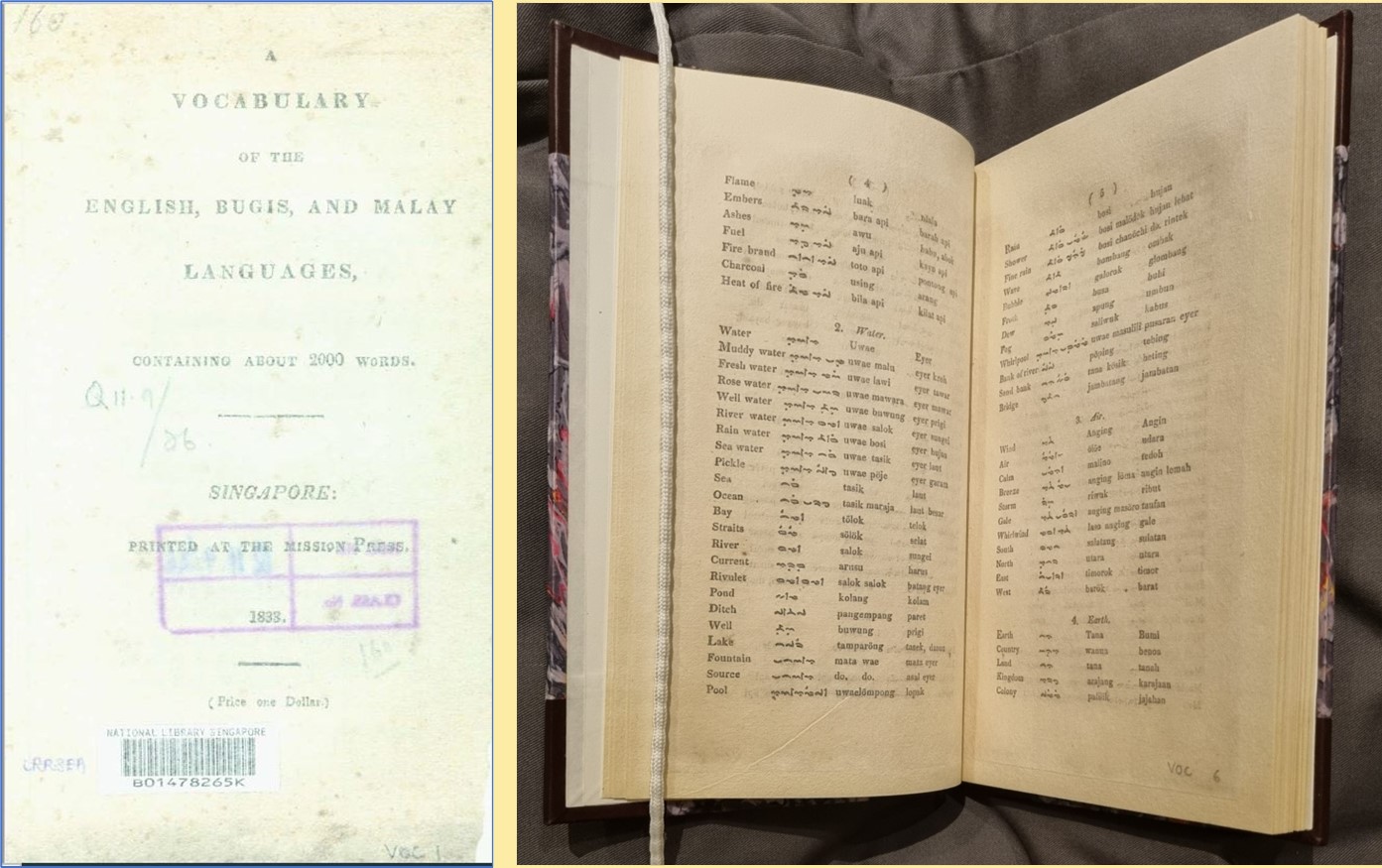

Singapore: Printed at the Mission Press, 1833.

Call no. RRARE 499.288.B8 VOC; Accession no. B01478265K.

First published in Melaka in 1820, this word list contains terms in English and Malay compiled by Claudius Henry Thomsen and Munshi Abdullah. This third edition, published in 1833, was expanded to include Bugis terms.

PUBLICATIONS BY THE MISSION PRESS OF THE AMERICAN BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS FOR FOREIGN MISSION

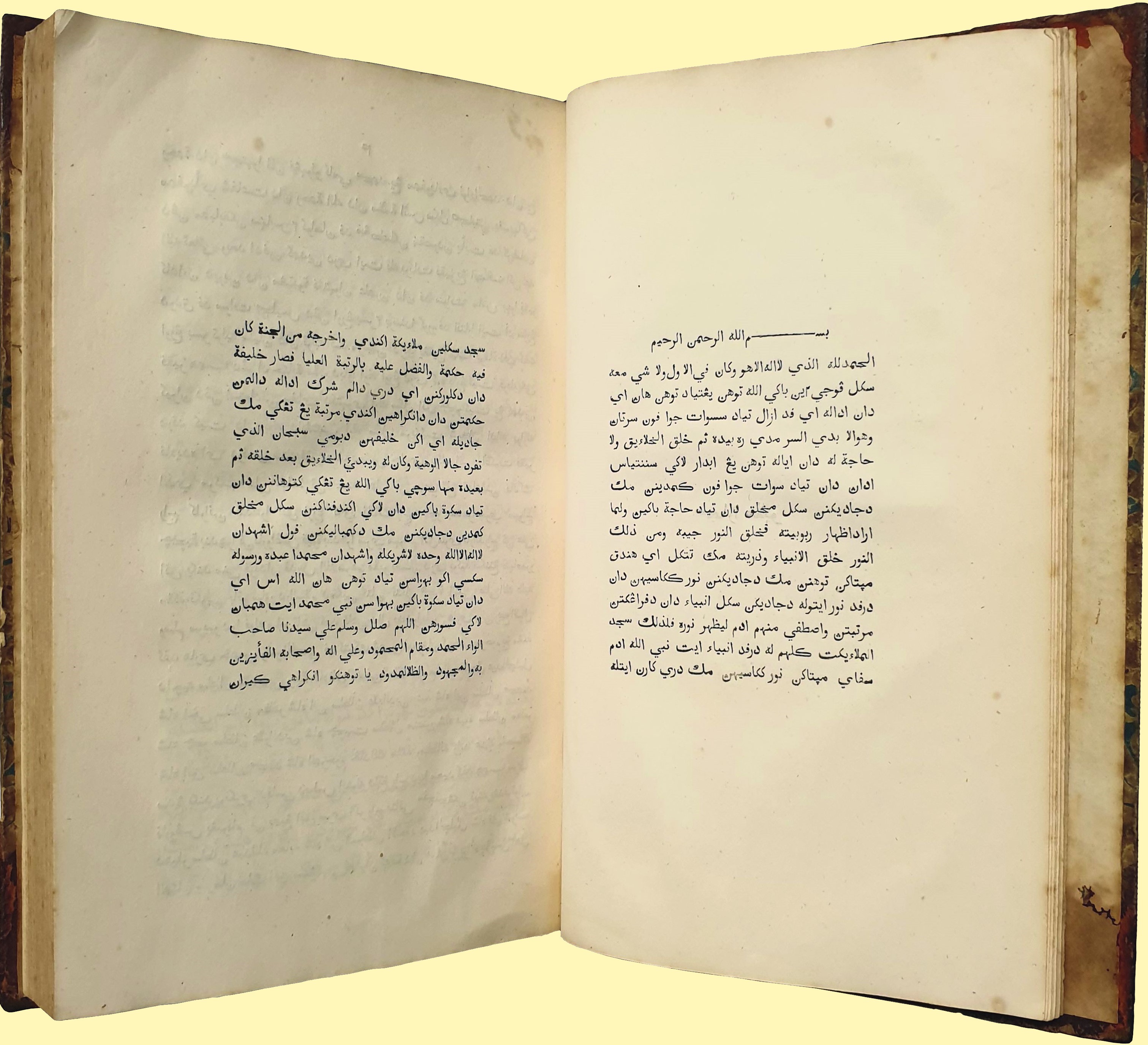

Singapore: 1840.

Call no. RRARE 959.503 SEJ; Accession no. B31655050C.

This is the first printed edition of the Sulalat al-Salatin (Genealogy of Kings). This version was edited by Munshi Abdullah and the preface was likely written by Alfred North, who also printed the book.

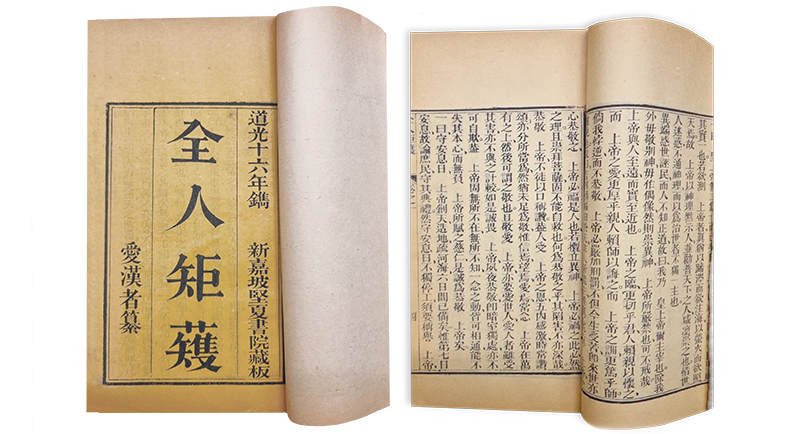

新嘉坡 坚夏書院, 1836.

Call no. RRARE 243 AHZ; Accession no. B02890695F.

The title of this publication has been translated as The Perfect Man’s Model or The Complete Duty of Man. This is the earliest locally printed Chinese book held in the National Library’s collection. This book was written by German Protestant missionary Karl Friedrich August Gützlaff under his pen name 爱汉者 (“Lover of the Chinese”) and by printed by 坚夏書院 (Jian Xia Shuyuan), the printing arm of the American mission in Singapore.

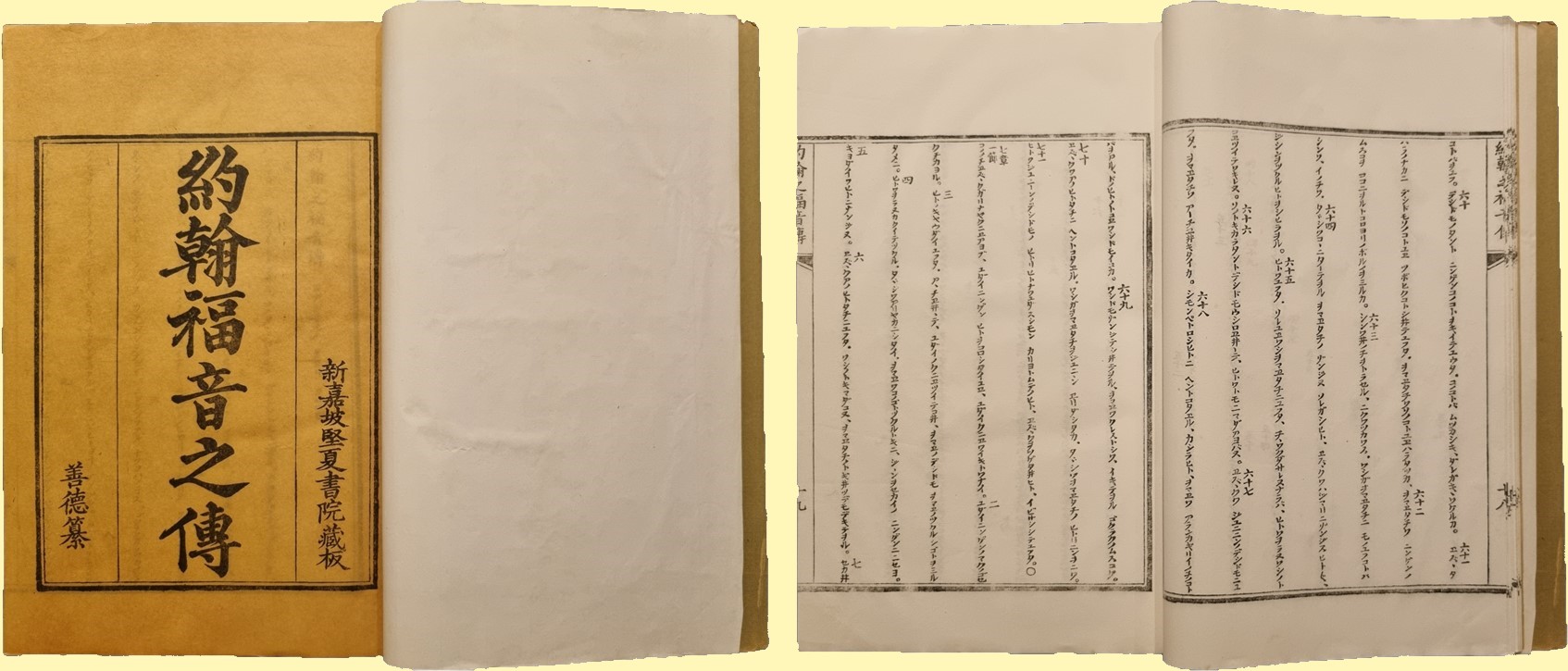

東京: 長崎書店 (Tōkyō: Nagasaki Shoten), 1941.

Call no. RCLOS 226.5 YOH-[LSB]; Accession no. B32428440E.

This is a facsimile reproduction of the 1837 edition of the Gospel of John, which scholars regard as the earliest extant book of the Bible in Japanese. It was translated by Gützlaff with the assistance of three shipwrecked Japanese sailors. One of the three, Yamamoto Otokichi, became the first Japanese settler in Singapore in 1862. Due to the closed-door policies of Japan and China at the time, Gützlaff had to send the text to Singapore for printing. The book cover credits 堅夏書院 (Kenka Shoin), the printing arm of the American mission in Singapore, as the publisher. The glaring errors in the katakana script are indications that the printing was likely undertaken by Chinese printers who did not know Japanese. This publication was donated to the National Library by Lim Shao Bin.

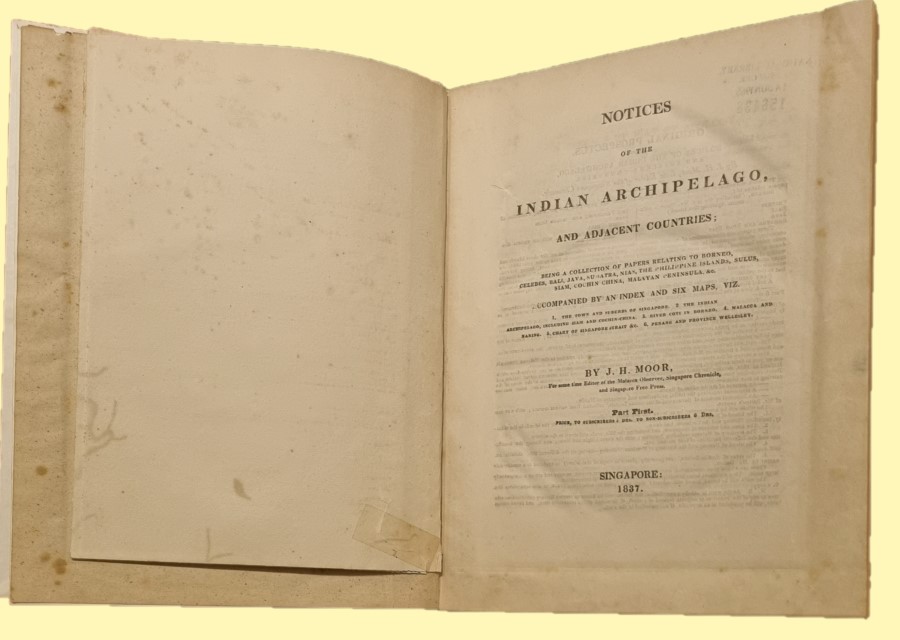

Singapore: 1837.

Call no. RRARE 991 MOO; Accession no. B03013554J.

This mammoth work features articles on Singapore and Southeast Asia reprinted from the Singapore Chronicle and other scholarly journals. It was compiled by John Henry Moor, the former editor of the Singapore Chronicle and Singapore Free Press. Due to the scarcity of printers and paper, the task took two years to complete. This is among one of the earliest scholarly works printed in Singapore. It was donated to the National Library by Mrs Loke Yew in fulfilment of the intention of her son Loke Wan Tho.

SELECTED WORKS BY BENJAMIN KEASBERRY

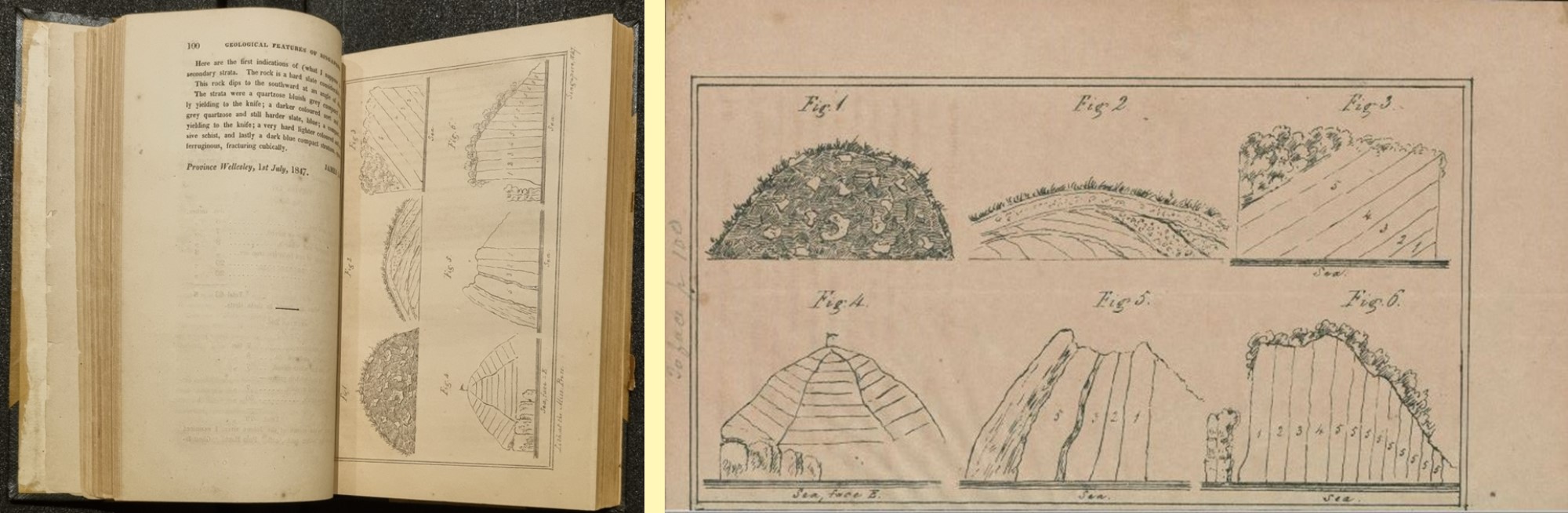

Singapore: Printed at the Mission Press, 1847–48.

Call no. RRARE 950.05 JOU; Accession nos. B03014400A (v. 1).

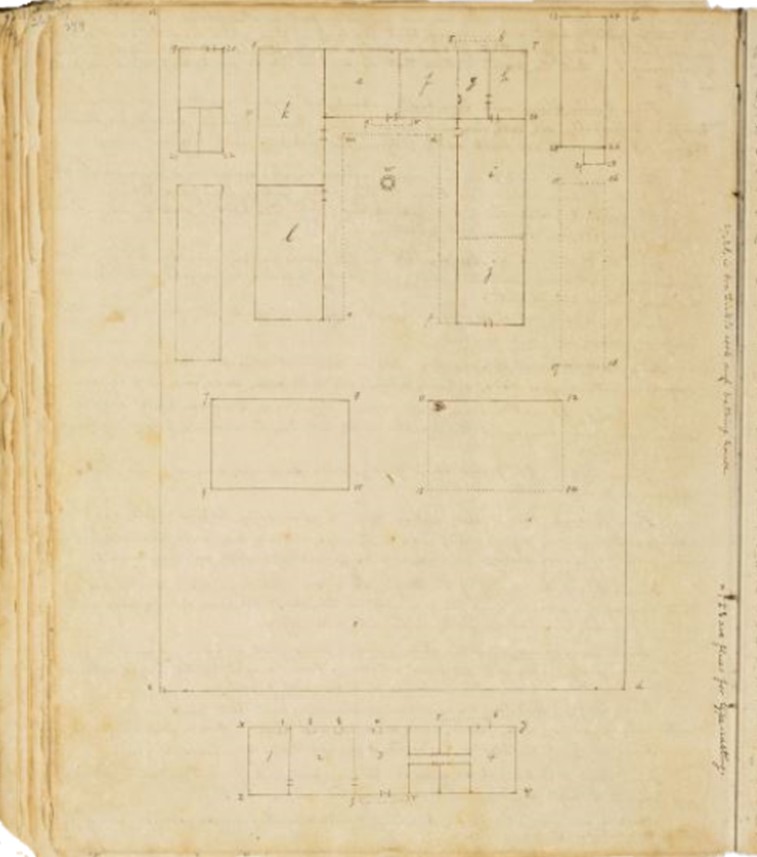

Commonly referred to as Logan’s Journal after its editor, the Scottish lawyer James Richardson Logan, this is one of the earliest scholarly periodicals published in Singapore. The periodical covered a broad range of topics ranging from history to the natural science of Southeast Asia, and was published in two series between 1847 and 1859. The first two volumes were printed at the Mission Press. The page featured is from an article on the geological features of Singapore published in volume 1. The illustrated plate on the right was lithographed at the Mission Press.

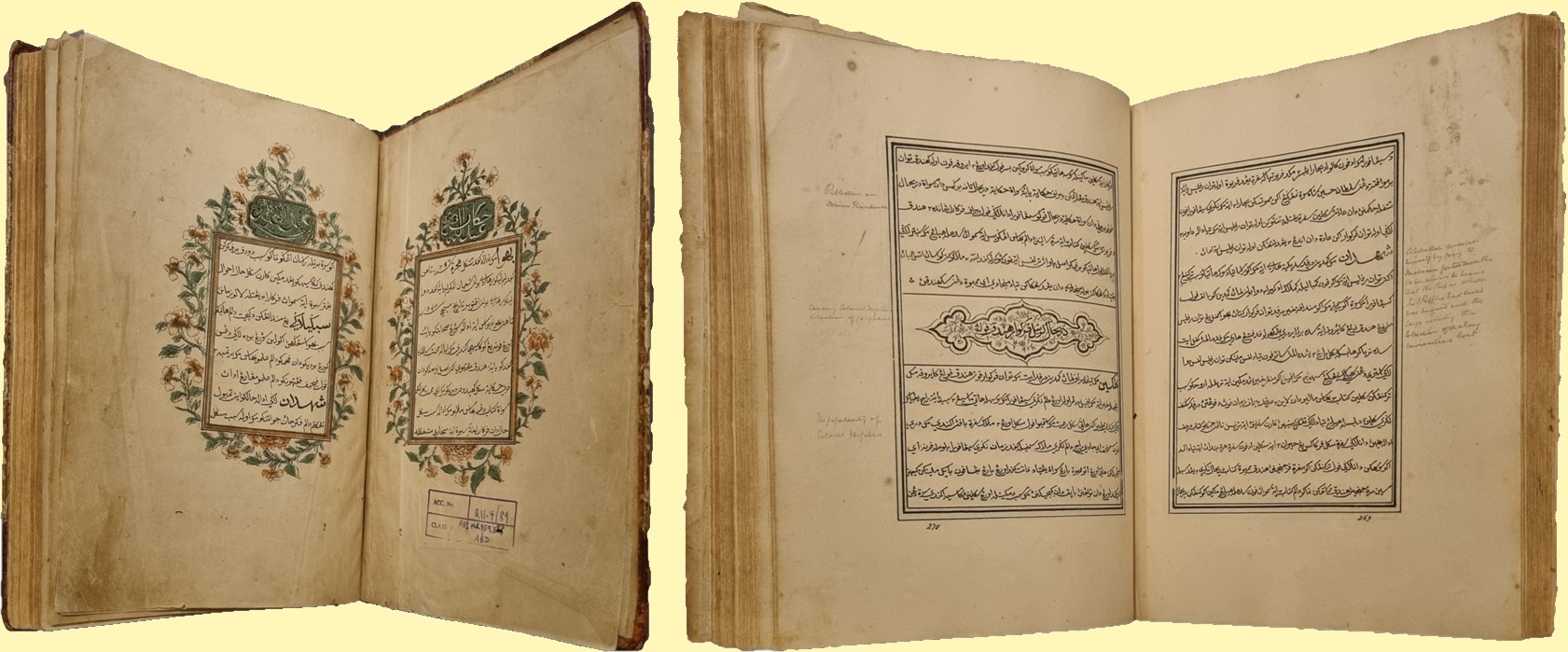

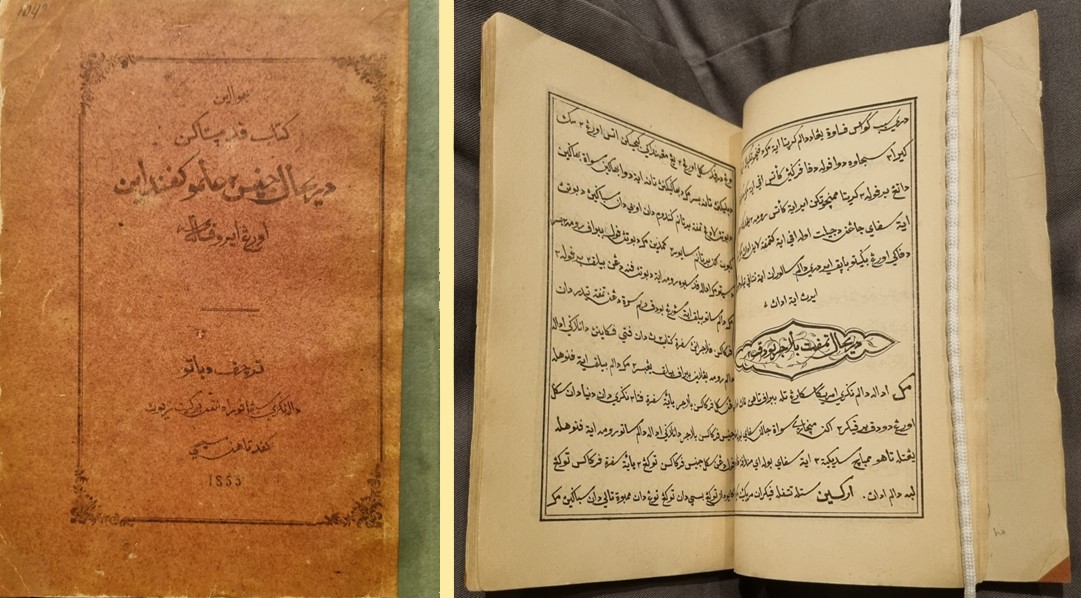

Singapore: Lithographed at the Mission Press, 1849.

Call no. RRARE 959.503 ABD; Accession no. B03014389F.

An iconic work in Malay literature and the history of Singapore, Hikayat Abdullah (Stories of Abdullah) – the autobiography of Munshi Abdullah – describes life in Singapore and Melaka in the early 19th century, including a detailed account of Stamford Raffles’ first arrival to Singapore in January 1819. This copy was donated by the Archdeacon George Frederick Hose in 1879 to the library of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. The book became a part of the Raffles Library (predecessor of the National Library) in 1923 when the society, which held its meetings at the Raffles Library and Museum, made a permanent loan of its collection to the library.

Singapore: Printed at the Mission Press for the British and Foreign Bible Society, 1853.

Call no. RRARE 225 BIB; Accession no.: B20119134J.

This translation of the Malay New Testament in Romanised Malay was edited and published by Benjamin Keasberry for the British and Foreign Bible Society in 1853. A revised edition was published in 1866.

Singapore: Bukit Zion, 1855.

Call no. RRARE 306.460973 CER; Accession no. B31655051D.

Roughly translated as The Book of European Knowledge, it was prepared by Munshi Abdullah for use in Benjamin Keasberry’s school. It covers various European modern technology and their social benefits, such as gaslights, water piping systems, railways and printing presses. The textbook was published at Mount Zion on River Valley Road, the location of the new mission office that Keasberry had established as an independent missionary after the London Missionary Society exited from Singapore in 1847.

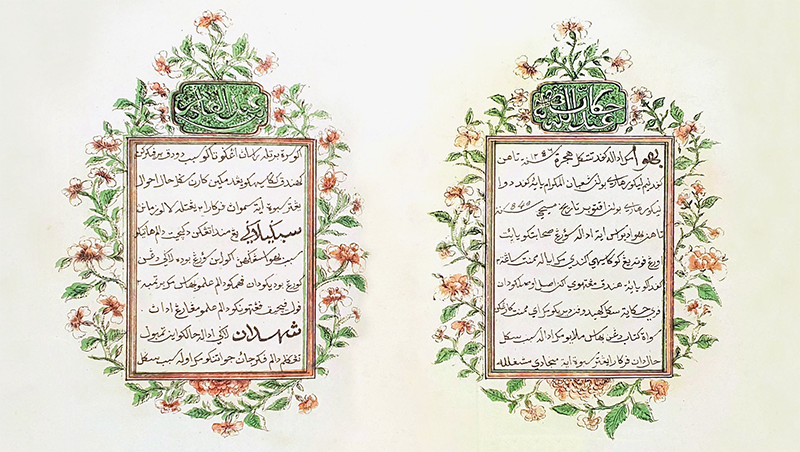

Singapore: Lithographed in Bukit Zion, 1859.

Call no. RRARE 059.9923 CER; Accession no. B03057034K.

Translated as Eye Glass for All Who Seek Knowledge, this is one of the earliest Malay periodicals published in Singapore. It showcases Benjamin Keasberry’s skill in utilising lithography to reproduce texts that are visually familiar to the calligraphic script, decorative motifs and bright colours of hand-copied Malay manuscripts.

REFERENCES

Abdullah Abdul Kadir, Hikayat Abdullah (Singapore: Mission Press, 1849). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RRARE 959.503 ABD)

Ang, Seow Leng, "Logan's Journal," BiblioAsia 11, no.4 (January-March 2016): 28–29.

Ang, Seow Leng, "Stories of Abdullah,” BiblioAsia 11, no. 4 (January–March 2016): 66–67.

“Extracts from Letters of Mr Tracy, Dated at Singapore,” The Missionary Herald 32, 181 (May 1836), HathiTrust, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.b3079719.

Hadijah Rahmat, Abdullah Bin Abdul Kadir Munshi: His Voyages and Legacies, and Colonial History, vol. 2 (Singapore: World Scientific, 2020), 90–91. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5 HAD )

J. Noorduyn, “C.H. Thomsen, the Editor of ‘A Code of Bugis Maritime Laws’,” Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 113, no. 3 (1957): 248, Brill website: https://doi.org/10.1163/22134379-90002285.

Kitab Al-kudus, Iya Itu, Injil Isa Al-Masihi Tuhan Kami = The New Testament of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ in Malay (Singapore: Printed at the Mission Press for the British and Foreign Bible Society, 1866. (From National Library, Singapore, call no.: RRARE 225.59923 BIB)

Kloss, C. Boden, Annual Report on the Raffles Library and Museum for the Year 1923 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1924), 6. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RRARE 027.55957 RAF)

Lee, Gracie, "The Book That Almost Didn't Happen," BiblioAsia 11, no.4 (January–March 2016): 36–37.

Mazelan Anuar, "Through the Eye Glass," BiblioAsia 11, no.4 (January–March 2016): 86–87

National Heritage Board, Perfect Man’s Model (Quanren Juyue) by Karl Friedrich August Gützlaff, Roots, last updated 6 April 2023, https://www.roots.gov.sg/Collection-Landing/listing/1339272.

Ong, Eng Chuan, "A Missionary's Guide to Java and Bali," BiblioAsia 11, no. 4 (January–March 2016): 12–13

Ong, Eng Chuan, "The Gospel in Chinese," BiblioAsia 11, no. 4 (January–March 2016): 96–97.

Orientalia II: Malaysia, Singapore, Borneo, John Randall Books of Asia, last accessed 19 July 2023, https://www.booksofasia.com/PDFs/Orientalia%202%20SEA%20CUR%2030.07.19.pdf.

Sachiko Tanaka and Irene Lim, "A Work of Many Hands: The First Japanese Translation of John’s Gospel and His Epistles," BiblioAsia 7, no. 4 (March 2012): 8–15.

Tan, Bonny, "Singapore’s First Japanese Resident: Yamamoto Otokichi," BiblioAsia 12, no. 2 (July–September 2016): 32–35.

The Chinese Repository, Vol. II. From May 1833 to April 1834, 2nd ed. (Canton: Printed for the Proprietors, 1834), 86, HathiTrust, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.b3883200.

“The President’s Address,” Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, no. 2 (December 1878): 4. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Twenty-First Annual Report of the American Tract Society 1835 (New York: Printed at the Society’s House, 1835), 49, HathiTrust, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.ah3ira.

Twenty-Eight Annual Report of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions September: 1837 (Boston: Crocker and Brewster, 1837), 90, HathiTrust, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/wu.89065737223.

Wylie, Alexander, Memorials of Protestant Missionaries to the Chinese (Shanghae: American Presbyterian Mission Press, 1867), 106, HathiTrust, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433068293772.

Gracie Lee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She works with the library’s rare materials collections, and enjoys uncovering and sharing the stories behind Singapore’s printed heritage.

Gracie Lee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She works with the library’s rare materials collections, and enjoys uncovering and sharing the stories behind Singapore’s printed heritage.NOTES

-

Cecil K. Byrd, Early Printing in the Straits Settlements, 1806–1858 (Singapore: National Library, 1970), 9–10, 13. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 686.2095957 BYR); Leona O’Sullivan, “The London Missionary Society: A Written Record of Missionaries and Printing Presses in the Straits Settlements, 1815–1847,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 57, no. 2 (247) (1984): 61–62, 67. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); Ching Su, “Printing Presses of the London Missionary Society Among the Chinese,” (PhD diss., University College London, 1996), 154–55, https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1317522/. ↩

-

Byrd, Early Printing in the Straits Settlements, 1806–1858, 13; O’Sullivan, “The London Missionary Society,” 64–66, 72–74. ↩

-

Byrd, Early Printing in the Straits Settlements, 1806–1858, 13. ↩

-

Byrd, Early Printing in the Straits Settlements, 1806–1858, 14, 24, Plate 4. ↩

-

Ching, “Printing Presses of the London Missionary Society Among the Chinese,” 154–55. ↩

-

Byrd, Early Printing in the Straits Settlements, 1806–1858, 14; O’Sullivan, “The London Missionary Society,” 74; John S. Bastin, Raffles and Hastings: Private Exchanges Behind the Founding of Singapore (Singapore: National Library Board Singapore and Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2014), 216. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5703 BAS); Hadijah Rahmat, Abdullah Bin Abdul Kadir Munshi: His Voyages and Legacies, and Colonial History, vol. 2 (Singapore: World Scientific, 2020), 90–91. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5 HAD); Raffles Museum and Library, “Proclamation by the Honble Sir Stamford Raffles Lieut. Governor of Fort Marlbro and Its Dependencies,” L17: Raffles: Letters to Singapore (Farquhar), 1 January 1823, Straits Settlements Records. (From National Archives of Singapore) ↩

-

Munshi Abdullah, The Hikayat Abdullah, trans. A.H. Hill (Kuala Lumpur: The Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 2009), 187–88. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.5 ABD) ↩

-

Ching, “Printing Presses of the London Missionary Society Among the Chinese,” 158; O’Sullivan, “The London Missionary Society,” 74, 77. ↩

-

O’Sullivan, “The London Missionary Society,” 77; Byrd, Early Printing in the Straits Settlements, 1806–1858, 13; Ching, “Printing Presses of the London Missionary Society Among the Chinese,” 156. ↩

-

O’Sullivan, “The London Missionary Society,” 77; Byrd, Early Printing in the Straits Settlements, 1806–1858, p. 13; Ching, “Printing Presses of the London Missionary Society Among the Chinese,” 156. ↩

-

Byrd, Early Printing in the Straits Settlements, 1806–1858, 14. ↩

-

Byrd, Early Printing in the Straits Settlements, 1806–1858, 14–15; O’Sullivan, The London Missionary Society,” 77–84. ↩

-

Ong Eng Chuan, “A Missionary’s Guide to Java and Bali,” BiblioAsia 11, no. 4 (January–March 2016): 12–13. ↩

-

J. Noorduyn, “C.H. Thomsen, the Editor of ‘A Code of Bugis Maritime Laws’,” Bijdragen tot de Taal-,Land- en Volkenkunde 113, no. 3 (1957): 248, https://doi.org/10.1163/22134379-90002285. ↩

-

Byrd, Early Printing in the Straits Settlements, 1806–1858, 14. ↩

-

Twenty-Third Annual Report of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, October 1832 (Boston: Crocker and Brewster, 1832), 98; Twenty-Sixth Annual Report of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, September 1835 (Boston: Crocker and Brewster, 1835), 69, HathiTrust, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/wu.89065737421. ↩

-

Ian Proudfoot, Transcription of The Journal of Alfred North, 1 August 1835–27 July 1836, Malay Concordance Project, last accessed 26 July 2023, https://mcp.anu.edu.au/proudfoot/North.pdf. ↩

-

Joseph Tracy, History of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, 2nd ed. (New York: M.W. Dodd, 1842), 308, HathiTrust, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.ah5evn. ↩

-

Munshi Abdullah, The Hikayat Abdullah, 290–91; Hadijah Rahmat, Abdullah Bin Abdul Kadir Munshi, vol. 2, 71–79, 94, 99–109. ↩

-

Twenty-Seventh Annual Report of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, September 1836 (Boston: Crocker and Brewster, 1836), 75, HathiTrust, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/wu.89065737421; Twenty-Eight Annual Report of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, September 1837 (Boston: Crocker and Brewster, 1837), 90; Thirty-First Annual Report of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, September 1840 (Boston: Crocker and Brewster, 1840), 140, 142, HathiTrust, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/wu.89065737223. ↩

-

Hadijah Rahmat, Abdullah Bin Abdul Kadir Munshi, 74. ↩

-

Ong Eng Chuan, “The Gospel in Chinese,” BiblioAsia 11, no. 4 (January–March 2016): 96–97; Twenty-Eight Annual Report of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, September 1837, 90; National Heritage Board, Perfect Man’s Model (Quanren Juyue) by Karl Friedrich August Gützlaff, Roots, last updated 6 April 2023, https://www.roots.gov.sg/Collection-Landing/listing/1339272. ↩

-

Report of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions Presented at the Thirty-Second Annual Meeting… 1841 (Boston: Crocker and Brewster, 1841), 144, HathiTrust, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015073264601. ↩

-

Mazelan Anuar, “Through the Eye Glass,” BiblioAsia 11, no. 4 (January–March 2016): 86–87. ↩

-

Gracie Lee, “Benjamin Keasberry,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 2016. ↩

-

The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 1840. (London: Thomas Ward and Co., 1840), HathiTrust, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.ah6ls8. ↩

-

Zhang Xiantao, The Origins of the Modern Chinese Press: The Influence of the Protestant Missionary Press in Late Qing China (New York: Routledge, 2007), 105–06. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. R 079.51 ZHA) ↩

-

Byrd, Early Printing in the Straits Settlements, 1806–1858, 5–6; Ching, “Printing Presses of the London Missionary Society Among the Chinese,” 258–83; Ibrahim Ismail, “Samuel Dyer and His Contributions to Chinese Typography,” Library Quarterly 54, no. 2 (April 1985): 157–69. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Byrd, Early Printing in the Straits Settlements, 1806–1858, 13, 17; Mazelan Anuar, “Early Malay Printing in Singapore,” BiblioAsia 13, no. 3 (October–December 2017): 40–43; Lee Ching Seng, “19th Century Printing in the Chinese Language,” in A General History of the Chinese in Singapore, ed. Kwa Chong Guan and Kwa Bak Lim (Singapore: Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations: World Scientific, 2019), 363–87. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 305.895105957); Lee Geok Boi, Pages from Yesteryear: A Look at the Printed Works of Singapore, 1819–1959 (Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society, 1989), 6. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 070.5095957 PAG) ↩