Kaboom! Early Malay Comic Books Make an Impact

The 1950s was the heyday for Malay comic books published in Singapore.

By Mazelan Anuar

When most people think about Malay comic books or comic book artists, the Malaysian artist Lat comes to mind. His distinctive drawings, which capture humorous slices of kampong life and life in the big city, have been tickling funny bones for several decades now.

Lat got his big break as an editorial cartoonist in Malaysia’s New Straits Times in the mid-1970s. In this way, he is part of a long tradition of Malay cartoonists who got their start in the local papers. In Singapore, some of the earliest editorial cartoons appeared in the 1930s in newspapers such as Warta Jenaka and Utusan Zaman.

Most of the published cartoons touched on issues of independence and anti-colonialism, in line with the spirit of the times to uplift the Malay community and encourage Malay nationalism. Attitudes and characteristics that were regarded as impeding the progress of the Malays were criticised, along with Western norms and culture. Cartoons and caricatures were effective tools for reaching people as these were presented in a simple and concise manner – often laced with irony, sarcasm and satire – for easier consumption by the masses.1

Interestingly, talented Malay writers and arts practitioners were drawn to this new art form that combined writing and art. They included writers like Abdul Jalil Haji Nor and the Indonesian artist and filmmaker Nas Achnas.

Malay Comics in Newspapers

One of the first Malay comics to appear came out in Warta Jenaka, which was launched in September 1936 as a weekly companion to Warta Malaya. Warta Malaya was a daily produced in Jawi that was published by Anglo-Asiatic Press on North Bridge Road. The first full-time cartoonist at Warta Jenaka was an artist by the name of S.B. Ally. Apart from Ally’s drawings, the newspaper also welcomed contributions from readers.2

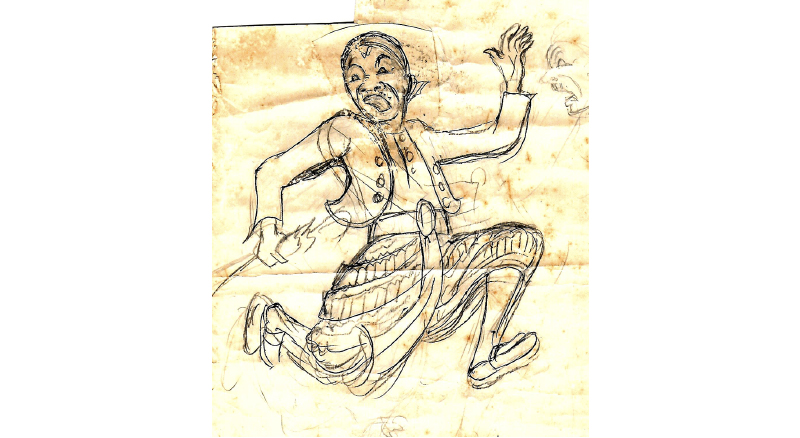

Not to be outdone, Utusan Melayu, another Jawi daily, also started a weekly supplement. Utusan Zaman was launched in November 1939 and the paper’s cartoonist was Ali Sanat. One of his popular creations was Wak Ketok – a satirical character known for his comical antics. The character was used to encourage unity in the Malay community and to improve their way of life.3

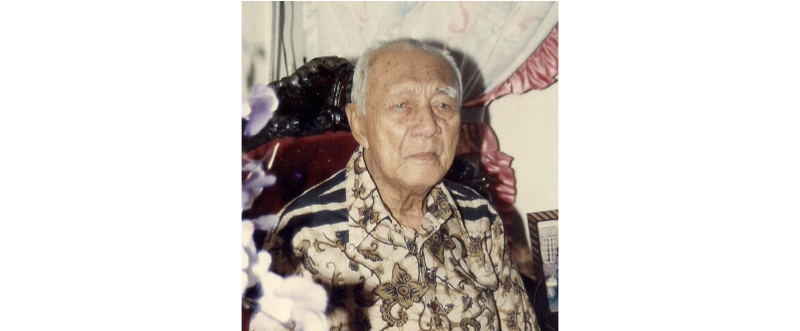

Ali Sanat was born in 1900 in Kampong Tembaga along Bussorah Street in Singapore. His father was a well-known Haj pilgrimage agent, who served pilgrims during their Singapore stopover en route to Mecca, and Ali Sanat helped his father manage these pilgrims.

In the early 1950s, Ali Sanat created a new character, Wak Raya, when he went to work for another newspaper, Melayu Raya. He also contributed his works to the entertainment magazine Asmara, but decided to stop drawing after 1956 to focus on his funeral business. He died in 1997, at age 97.4

Cartoons and caricatures continued to be featured in the columns of Malay newspapers in the 1940s. After the Japanese surrender in 1945, cartoons started appearing in Malay magazines and this paved the way for full-fledged comic books in Malay.

Hang Tuah for Children

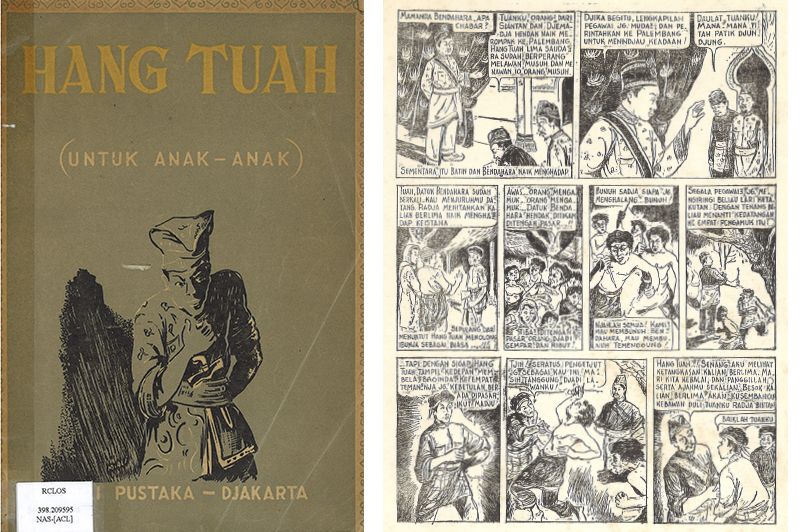

In 1951, Balai Antara published what is believed to be the first Malay comic book in Indonesia. Created by writer and artist Nasjah Djamin, Hang Tuah (Untuk Anak-Anak), a comic for children in Romanised Malay, chronicles the heroics of the legendary Malay warrior Hang Tuah.5

Born in Sumatra in 1924, Nasjah Djamin was an artist and a writer. During the Indonesian National Revolution (1945–49), he created posters and slogans with other artists. In 1949, he began working for Balai Pustaka (originally known as Kantoor voor de Volkslectuur), a body that had been established by the Dutch in 1908 to select suitable reading materials for schools and, at the same time, restrict published materials that were critical of Dutch rule and policies.6 He then joined the editorial team for the magazine Budaya in 1953. Apart from drawing, Nasjah Djamin also wrote plays and short stories, and dabbled in theatre.7

First-Ever Malay Story in Pictures

Probably caught unawares that it had been beaten to the punch by Hang Tuah (Untuk Anak-Anak), the comic book Pusaka Datuk Moyang (Treasure of the Ancestors), published in 1952, proudly proclaims on its cover that it was the “First-ever Malay story in pictures” (Julung kali cerita Melayu bergambar).8

It was a small comic book, just 32 pages on paper measuring 8.5 cm wide and 13.5 cm long. The handwritten Jawi text had to be squeezed into what little space that was available, which makes reading the comic somewhat difficult. This also makes it hard sometimes to identify the different characters that are drawn. Nonetheless, the comic was a brave effort that pioneered the publishing of Malay comic books in Singapore.

Pusaka Datuk Moyang tells the story of a feud between two noble families lasting several generations. The main character, Datuk Pahlawan Sebilah, fought to take back the rights of his family, and many were sacrificed in battles as both parties launched attacks on one another.

This comic was published by Nilam, which used the office of Royal Press, a publishing company located at 745 North Bridge Road and well known for its magazine, Hiburan. Unfortunately, Nilam did not last long and so far, only two publications by Nilam have been found. The other title is also a comic book and published later in the same year featuring two stories – “15 Tahun Dahulu” and “Si Labu Dengan Si Kundur”.

Pusaka Datuk Moyang was written by Abdul Jalil Haji Nor, using the pen name Merayu Rawan. Abdul Jalil was a founding member of Angkatan Sasterawan ’50 (Asas ’50), an important Malay literary organisation based in Singapore. He was born in Johor in 1922 but grew up in Singapore. In the 1940s, he joined Annies Printing Works in Johor where he produced several novelettes, before working in Singapore for Royal Press and Harmy Press.

The prolific writer and editor Harun Aminurrashid played a major role in the publication of Pusaka Datuk Moyang. In the foreword of the book, the Malay literary pioneer wrote that Pusaka Datuk Moyang was initially published as a series in Hiburan. As the story was well received by the magazine’s readers, Harun encouraged the creator to compile it into a book. He opined that comic books are useful in teaching the young to be loyal, strong, well behaved and progressive.9

Majalah Comics Melayu

Over in Johor Bahru, publisher and printer Sabirin Haji Mohd. Annie initiated the series Majalah Comics Melayu (Malay Comics Magazine) in 1952 to compete with Nilam. The series, comprising 11 comic books, was published by Zawiyah Publishing House and printed by his company, Annies Printing Works. Seven out of the 11 books were drawn by Razak Ahmad.

According to Razak, Harun Aminurrashid’s call for the production of Malay comic books moved him to take up the challenge. The comic books were based on stories relating to Malay history and legends and to make the books more accessible to the public, Zawiyah used Romanised Malay instead of Jawi script.10

The Works of Nas Achnas

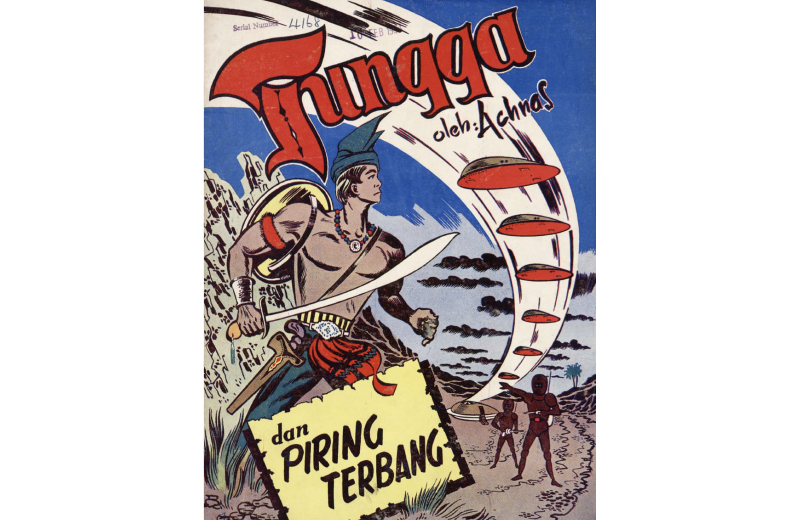

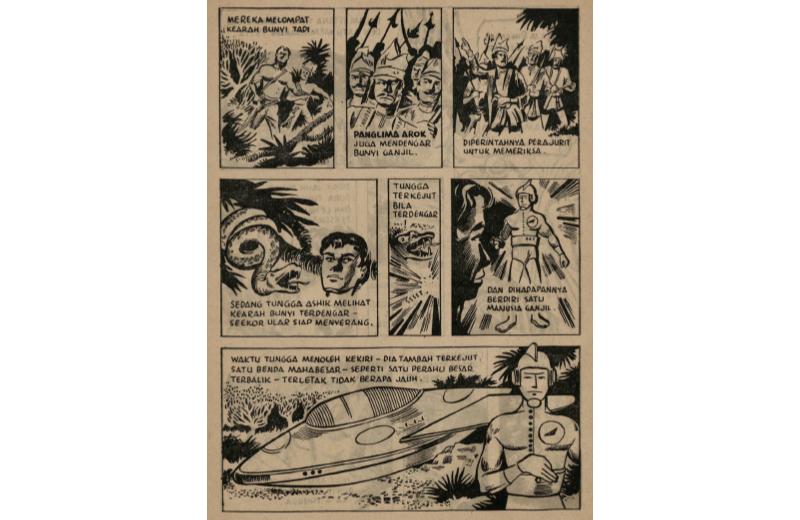

One interesting work that emerged during those early years was Tungga dan Piring Terbang (Tungga and the Flying Saucer). This comic book was published in 1953 by Malayan-Indonesian Book Store (MIBS) and was the creation of Indonesian filmmaker and comic artist Nas (also known as Naz) Achnas.11 This comic book was a groundbreaking effort because at the time, Malay comic books typically depicted tales from ancient Malay hikayat (meaning “stories” in Arabic). Written in Romanised Malay, Tungga dan Piring Terbang is regarded as one of the earliest Malay science fiction comic books published in Singapore. Interestingly, Tungga and the other human characters resemble Malay warriors and nobility of the past.

Tungga protects the crown prince, Lewangsa, after a revolt that results in the king’s death. While escaping, Tungga and Lewangsa encounter aliens who help them. Eventually, Tungga and Lewangsa manage to claim back the throne. Later, the aliens become disillusioned and disappointed by human greed and their penchant for fighting.

However, Nas Achnas was more notable as a film-maker and his involvement in publishing received scant attention. The films he directed include Pelangi (1951), Dosa Remaja (1973) and Bunga Mas (1973).12 After meeting Harun Aminurrashid sometime after the Japanese Occupation, Nas Achnas assisted Harun to establish Kenchana, a monthly news magazine published by MIBS, in 1947.

Nas Achnas created a comic series, Tunggadewa, that was featured in Kenchana. It is believed that this comic series was subsequently compiled and republished as a graphic novel although no copy of the book has ever been found, unfortunately. The cartoons by Nas Achnas, which were often a social commentary on Indonesian politics, were also featured in the entertainment magazine Hiburan.13

Geliga Press

Another publishing company in Singapore that waded into the business of publishing Malay comic books was Geliga Press established by Syed Omar Abdul Rahman Alsagoff in 1954. Beside publishing novels for adults and storybooks for children, it also produced magazines such as Remaja, Asmara and Suara Merdeka that were popular with the Malay community.14

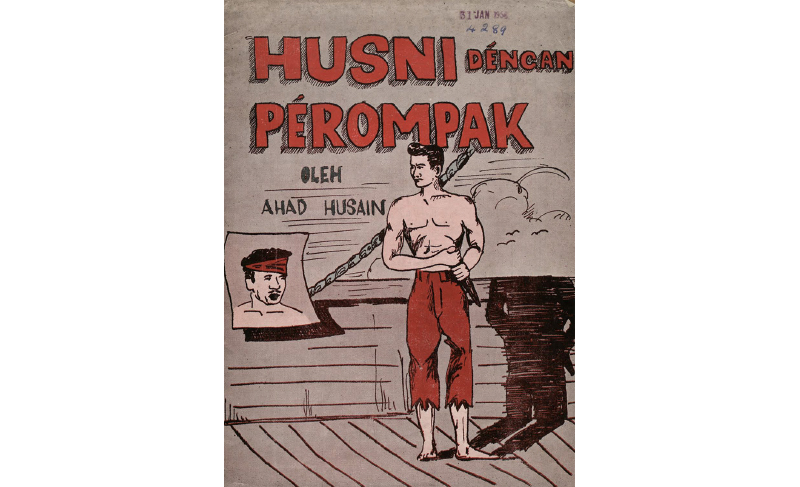

In 1956, Geliga decided to publish its first comic book – Husni Dengan Perompak (Husni and the Robbers).15 It then went on to produce other comic books, collaborating with artists and writers such as Raja Hamzah, K. Bali and Nora Abdullah.

Raja Hamzah was a prolific comic artist in Malay newspapers. Lat credited Raja Hamzah as an inspiration and influence. Raja Hamzah’s series of cartoons and comics appeared in Utusan Melayu and, later, Berita Harian. Dol Keropok, Wak Tempeh and Keluarga Mat Jambol were the early cartoon series that made him popular. His works continued to be published in Berita Harian and Berita Minggu until his death in 1981.16

K. Bali was the pen name of the multi-talented Abdul Rahim Abdullah. Born in Kelantan in 1933, he was a Malay and Thai language teacher as well as chief editor for the newspaper, Utusan Rakyat. Apart from drawing cartoons and comics, K. Bali also wrote poems, short stories, drama, novels, essays and articles that were published in newspapers and magazines such as Juita Filem, Hiburan, Mutiara and Mastika. He was conferred the Ahli Mangku Negara (Member of the Order of the Defender of the Realm) in 1984 and Ahli Darjah Kinabalu (Member of the Order of Kinabalu) in 1986.17

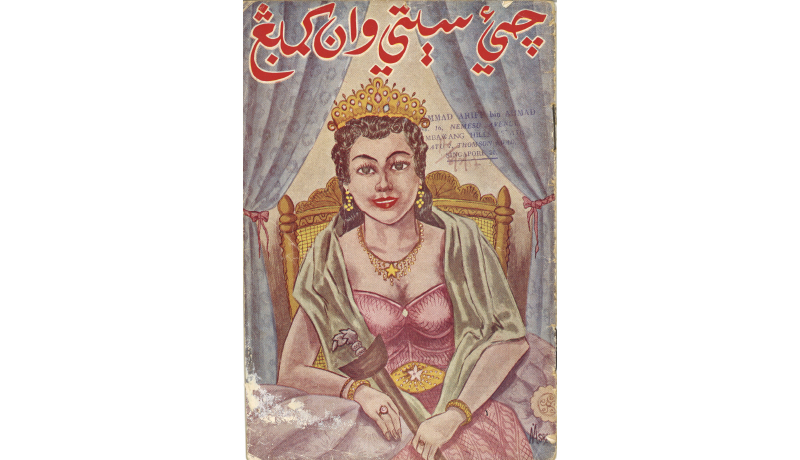

Geliga’s first female cartoonist was Nora Abdullah, whose real name was Che Nor Zaharah Abdullah.18 She was also the first female Malay comic artist in Singapore and Malaya. Born in Kelantan, Nora Abdullah published her first comic book, Cik Siti Wan Kembang, in 1955 at the age of 15.19 Siti Wan Kembang, known for her wisdom and mystical powers, is the name of the legendary queen who ruled Kelantan in the 17th century. Nora Abdullah published at least 12 comic books with Geliga but stopped drawing comics in 1960 and turned to painting portraits instead.20

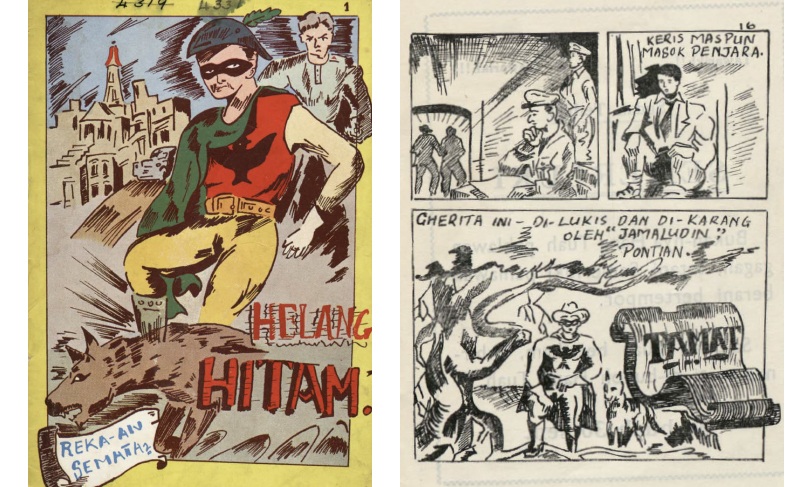

Geliga also published the popular Geliga Komik Series (Geliga’s Comic Series) comprising more than 300 comic books. The second book in the series is titled Helang Hitam, published in 1956. Helang Hitam – meaning “Black Eagle” – is the alter ego of Harun and a cross between Robin, Batman’s sidekick, and the legendary outlaw Robin Hood. The villain in the story is Keris Mas, who robs a bank with his gang and escapes to a hideout on a deserted island. Helang Hitam manages to defeat and arrest Keris Mas, who is then put behind bars.21

Geliga was a major publisher of comic books, and when it closed in the early 1960s, the production of comic books in Singapore declined. Comic artists also stayed away due to issues relating to payment of royalty fees.22 Nora Abdullah’s comic book Armina, published in 1961 (number 309 under the Geliga Komik Series), was likely Geliga’s last comic book.23

In the 1960s, the Malay comic book publishing trade began shifting its centre from Singapore to Penang where Sinaran Brothers became the most prolific publisher of Malay comic books. Penang eventually supplanted Singapore as a centre for publishing Malay comic books.

Mazelan Anuar is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. His research interests are in early Singapore Malay publications and digital librarianship. He manages the National Library’s Malay-language collection as well as the NewspaperSG portal.

Mazelan Anuar is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. His research interests are in early Singapore Malay publications and digital librarianship. He manages the National Library’s Malay-language collection as well as the NewspaperSG portal.NOTES

-

Muliyadi Mahamood, Kartun dan Kartunis di Malaysia (Kuala Lumpur: Institut Terjemahan & Buku Malaysia, 2015), 3–5. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 741.59595 MUL); Muliyadi Mahamood, Dunia Kartun: Menyingkap Pelbagai Aspek Seni Kartun Dunia dan Tempatan (Kuala Lumpur: Creative Enterprise, 2010), 148–50. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RART 741.5 MUL) ↩

-

Muliyadi Mahamood, The History of Malay Editorial Cartoons (1930s–1993) (Malaysia: Utusan Publication & Dist., 2004), 17–20. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RART 741.59595 MUL) ↩

-

“Haji Ali – Kartunis Yang Hangat di Zaman Silam,” Berita Harian, 1 October 1985, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Wak Ketok Perintis Kartun Melayu,” Berita Harian, 7 February 2015, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Jan Van Der Putten and Timothy P. Barnard, “Old Malay Heroes Never Die,” in Ian Gordon and Mark Jancovich, Film and Comic Books (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2012), 668–69. (From NLB OverDrive); Nasjah Djamin, Hang Tuah (Untuk Anak-Anak) (Djakarta: Balai Pustaka, 1951). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 398.209595 NAS-[ACL]) ↩

-

“Balai Pustaka,” in Ensiklopedia Sejarah dan Kebudayaan Melayu (Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, Kementerian Pendidikan, Malaysia, 1999), jil. 1 A-E. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. R 959.003 ENS); Van Der Putten and Barnard, “Old Malay Heroes Never Die,” 668–69. ↩

-

“Nasjah Djamin,” in Ensiklopedia Sejarah dan Kebudayaan Melayu (Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, Kementerian Pendidikan, Malaysia, 1999), jil. 3 M-Q. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. R 959.003 ENS) ↩

-

Merayu Rawan, Pusaka Datuk Moyang (Singapore: Nilam, 1952). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS Malay 741.5 MER) ↩

-

Annabel Teh Gallop, “Malay Comic Books from the 1950s and 1960s in the British Library,” Southeast Asia Library Group Newsletter, no. 54 (December 2022): 47–48. Southeast Asia Library Group, https://web.archive.org/20230202094121/seal.org/pdf/newslatter2022.pdf. ↩

-

Gallop, “Malay Comic Books from the 1950s and 1960s in the British Library.” ↩

-

Naz Achnas, Tungga dan Piring Terbang (Singapore: Malayan-Indonesian Book Store, 1953). (From National Library, Singapore); “Achnas, the Film-maker, Goes into Action,” Straits Times, 13 March 1955, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Pengkritik2 Pasti Bidas Hebat ‘Dosa Remaja’,” Berita Harian, 20 May 1973, 11; “Bunga Mas Dijangka Jadi Filem Merdeka yg Terbaik Tahun Ini,” Berita Harian, 18 August 1973, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Van Der Putten and Barnard, “Old Malay Heroes Never Die,” 804. ↩

-

“Geliga Limited,” in Ensiklopedia Sejarah dan Kebudayaan Melayu (Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, Kementerian Pendidikan, Malaysia, 1999), jil. 1 A-E. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. R 959.003 ENS) ↩

-

Ahad Husain, Husni Dengan Perompak (Singapore: Geliga Limited, 1956). (From PublicationSG) ↩

-

Muliyadi Mahamood, Dunia Kartun: Menyingkap Pelbagai Aspek Seni Kartun Dunia dan Tempatan (Kuala Lumpur: Creative Enterprise, 2010), 158–59. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RART 741.5 MUL) ↩

-

“K. Bali,” in Ensiklopedia Sejarah dan Kebudayaan Melayu (Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, Kementerian Pendidikan, Malaysia, 1999), jil. 2 F-L. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. R 959.003 ENS) ↩

-

Jacqueline Lee and Chiang Yu Xiang, “Singapore Comics: Panels Past and Present,” BiblioAsia 17, no. 3 (October–December 2021): 4–11. ↩

-

Nora Abdullah, Cik Siti Wan Kembang (London: The British Library, 2010–2013). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Malay RCLOS 899.28 NOR) ↩

-

“Pelukis Nora Maseh Tetap Melukis,” Berita Harian, 7 September 1969, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Jamaludin, Helang Hitam (Singapura: Geliga, 1956). (From PublicationSG) ↩

-

“Kelumpohan Peluksis2 Komik Melayu,” Berita Harian, 16 March 1962, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Nora Abdullah, Armina (Singapura: Geliga, 1961). (From PublicationSG) ↩