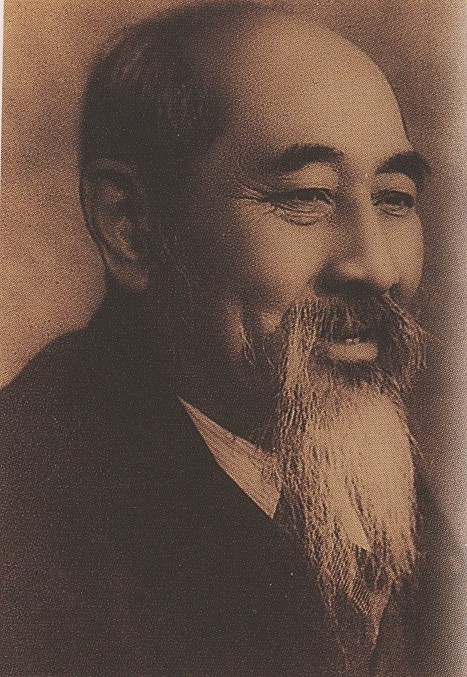

Of Towchangs and the ‘Republic Beard’: Dr Lim Boon Keng’s Life and Achievements

A prominent pioneer of early Singapore, Dr Lim Boon Keng was an accomplished businessman and doctor. He also contributed his time and efforts to resolve various issues faced by the Chinese community during the colonial times.

By Ang Seow Leng

A Remarkable Man

A prominent pioneer of early Singapore, Dr Lim Boon Keng was an accomplished businessman and doctor. He also contributed his time and effort to resolving the various issues faced by the Chinese community during the colonial times.

As one of the respected Chinese leaders in Singapore, he advocated several social reforms through his writings and debates in the Chinese Philomathic Society, which he cofounded with community leader Song Ong Siang. Convinced that Confucianism would be the way for the Chinese community to improve, he was passionate about having all Chinese learn the Chinese language. He also participated in creating a milestone in China’s history with Dr Sun Yat-sen, and spent 16 years of his life heading Xiamen University (Amoy University) as its president.

This remarkable man was born on 18 Oct 1869. A third generation Straits Chinese, Dr Lim Boon Keng’s life and experiences were closely linked to the developments of the British colonial powers in the region and China at the turn of the century. His ability to deal with both the colonial powers and the Chinese government allowed him to fully use his potential and capabilities.

Lim Boon Keng, The Doctor

Dr Lim’s education started out with a brief stint at a school set up by the Hokkien Clan Association, where he learnt Chinese classics. He then moved on to the Government Cross Street School to start his English education, then on to Raffles Institution. He was nearly unable to complete his education because of financial difficulties resulting from his father’s death, but the headmaster of Raffles Institution, Mr R.W. Hullett, provided financial assistance and moral support (Song, 1984).

The young man did not disappoint the headmaster. After finishing school at Raffles Institution, he won a Queen’s Scholarship in 1887 to study at the University of Edinburgh for six years, graduating in medicine and surgery with first class honours in 1892.

He was also a Fellow and one-time President of the Royal Medical Society, as well as research scholar in pathology at Cambridge University. When asked at the age of 80 what his happiest memories were, he fondly recounted his school days and the words of wisdom that the RI headmaster had shared with him before he left for London: “You are a Chinese going to the West and remember to respect yourself and do right. Never mind what other people, the rich and the influential, may think of you. As long as you do right and remain right, you will always be happy” (Ferroa, 1948).

Upon returning to Singapore in 1893, the young doctor set up a clinic at Telok Ayer Street. He also gave a course of seven lectures on ‘First Aids in Ambulance’ during what was supposed to be a fortnightly meeting of the Chinese Christian Association. It was well attended by 35 participants (Straits Chinese Magazine, 1898).

His contributions to the medical field extended beyond Singapore shores. Apart from being the medical delegate of the Chinese Government to Paris and Rome at the Conference Sanitaire Internationale, Dr Lim was also the Medical Director of the Chinese Section of the International Hygiene Exhibition in Dresden. Back home in Singapore, he raised funds for the founding of the King Edward VII Medical School in 1905, and volunteered to be a lecturer on Pharmacology and Therapeutics, and Materia Medica at the same school. He also co-founded the Anti-Opium Society in 1906, and in 1912, was made president of the Board of Health in the Republican Government at Nanking.

In 1895, at a young age of 26, Dr Lim was appointed as a Chinese member of the Straits Settlements Legislative Council. For more than 10 years, he was nominated repeatedly for this position. For several years, he also served as a Justice of Peace, a Municipal Commissioner and a member of the Chinese Advisory Board. He was also very active in participating in major events related to the British colonial government, attending the coronation of King Edward VII and King George V in 1902 and 1911 respectively (Song, 1984). He even wrote an article about the Diamond Jubilee in the Straits Chinese Magazine in 1897.

Lim Boon Keng, The Businessman

Lim Boon Keng’s business acumen led him to initiate rubber planting in Malaya, after listening to the advice of Henry Nicholas Ridley, then the Director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens. Believing that there would be good prospects for this business venture, Dr Lim pioneered large-scale rubber planting with Mr Tan Chay Yan of Malacca. Those who heeded his call to start rubber plantations enjoyed a booming success.

The accomplished businessman also helped to establish the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce in 1906, joining the Chamber as a member. He also established three banks with other prominent Straits Chinese: the Chinese Commercial Bank, the Ho Hong Bank and the Oversea-Chinese Bank.

Being passionate about improving the life of Straits Chinese and the Chinese community, Dr Lim and his friends also formed a number of societies, started a magazine, ran a newspaper, founded a school for girls and started a Mandarin class.

Lim Boon Keng, The Education Advocate

In 1896, he started the Chinese Philomathic Society with the support of other prominent Chinese. The Society’s main focus was to study English literature, Western music and the Chinese language. In 1919, together with Tan Jiak Kim, Seah Liang Seah and Song Ong Siang, Dr Lim co-founded the Straits Chinese British Association, which served as a voice for the Straits Chinese, and was elected president twice in its first two decades. He was also a member of the Ee Hoe Hean Club, which was set up in 1895 and is one of the oldest Chinese clubs in Singapore.

Concerned by the low literacy levels of Straits Chinese women, Dr Lim co-founded the Singapore Chinese Girls’ School with Song Ong Siang in 1899. That year, on 1 July, the school opened with seven Straits Chinese girls as students. It was located at the junction of Hill Street and Armenian Street, next to the Masonic Hall, (Ooi, 1999).

In an attempt to popularise the learning of Mandarin, he started Mandarin classes in his house in 1898, drawing a steadily increasing number of students. The “old and young were attracted not only by his new method of teaching Chinese, but also by his eloquent lectures on Confucius and Confucian teachings … “ (Kiong, 1907).

Dr Lim also urged the use of Chinese as a medium of instruction for Chinese children, in addition to English. In one of the issues of the Straits Chinese Magazine, he wrote that it was impossible to cut adrift from a nation all its traditions and yet expect it to prosper; for far away from its historical and radical connections, a people, like a tree severed from its roots, must wither away and degenerate (Lim, 1897). He believed that Chinese children should be trained in two languages, so as to retain their ethnic roots while still being able to contribute to the society economically.

Lim Boon Keng, The Patriot

Apart from serving the Chinese community in Singapore, he also played a large role in the politics of China as an overseas Chinese. In 1900, when China’s prominent reform movement leader Kang Youwei was in exile in Singapore, Dr Lim was briefly involved in ensuring his safety. Later, Dr Lim assisted Dr Sun Vat-sen in raising funds and recruiting supporters.

He recalled later that after attending the coronation of King George V in 1911, he went to Dresden, Germany, where he took charge of the Chinese pavilion at a Health and Hygiene Exhibition. When he received news of the Chinese Revolution, he immediately left for China and stayed at Hankow with Dr Sun Vat-sen. While in China, he witnessed the birth of the Chinese Republic. The training that he had received during the four years he spent with the Chinese Company of the Singapore Volunteer Infantry from 1901 was likely put to good use then (Ferroa, 1948).

During the days of the revolution, Dr Lim grew a beard which he called the “Republic Beard”. He kept it for the rest of his life. In 1911, he was appointed medical adviser to the Chinese Ministry of the Interior as well as Inspector-General of Hospitals in Peking, and in 1912, as confidential secretary and personal physician to Dr Sun Yat Sen. He became one of the original principal officials of Singapore’s Kuomintang branch in 1913 (Png, 1961).

When World War I broke out, he put his talent in fund raising to use again, lending his support to the British colonial government by getting Straits Chinese to contribute funds to the Prince of Wales Relief Fund and towards the purchase of warplanes.

Dr Lim’s relationship with China did not end there. In 1921, at the age of 52, he accepted Tan Kah Kee’s invitation to be the president of Xiamen University (University of Amoy), and for the next 16 years, devoted himself to running the University.

When the Depression came about in 1929, it threw more challenges at the pioneer. Insufficient funds prompted him to travel to the Philippines, Indonesia and Singapore to secure funds from overseas Chinese for the university. Unfortunately, he could not get along with lecturers and students who did not agree with his education ideology (.!:I’, 1985). All these contributed to his resignation from the university later, after which he finally settled down in Singapore for good in 1937.

In 1942, World War II broke out in Singapore. At the age of 73, Dr Lim was forced by the Japanese to lead the Overseas Chinese Association. Surrounded by Japanese spies and informers and the Kempeitai,1 the Association was formed by the Japanese to serve the needs of the Chinese community. Dr Lim was ordered to raise a ‘donation’ of $50 million for Japan on behalf of all Malayan Chinese. He alone was expected to come up with $2,200. Unable to meet this request, he took to drinking to forget his worries.

Fortunately, his former students helped him raise the sum. However, it was an impossible task to raise $50 million. When the deadline was up, Chinese leaders from all the states had to suffer verbal abuses. Dr Lim gave an emotional retort, “We never told a lie. When we promised to give the military contribution, we meant to do it. Financial conditions are now such as to be beyond our control. If we are unable to pay, then die we will. I wish to point out, however, that the manner in which the Government raises this military contribution is without any parallel in any country” (Tan, 1947). This issue was solved later with a loan from the Yokohama Specie Bank for the outstanding $22 million.

The Japanese did not pass up any opportunities to make use of Dr Lim while carrying out their propaganda activities. A member of Force 136, Lin Jinquan, remembered that Dr Lim was so upset by a Japanese that he attempted to commit suicide. Another Force 136 member, Lin Shuyan, also recalled that Dr Lim would get drunk and say he wanted to dance. Once, while drunk, he cried and said that he should not have done all the things he had been doing (1985).

Lim Boon Keng, The Author

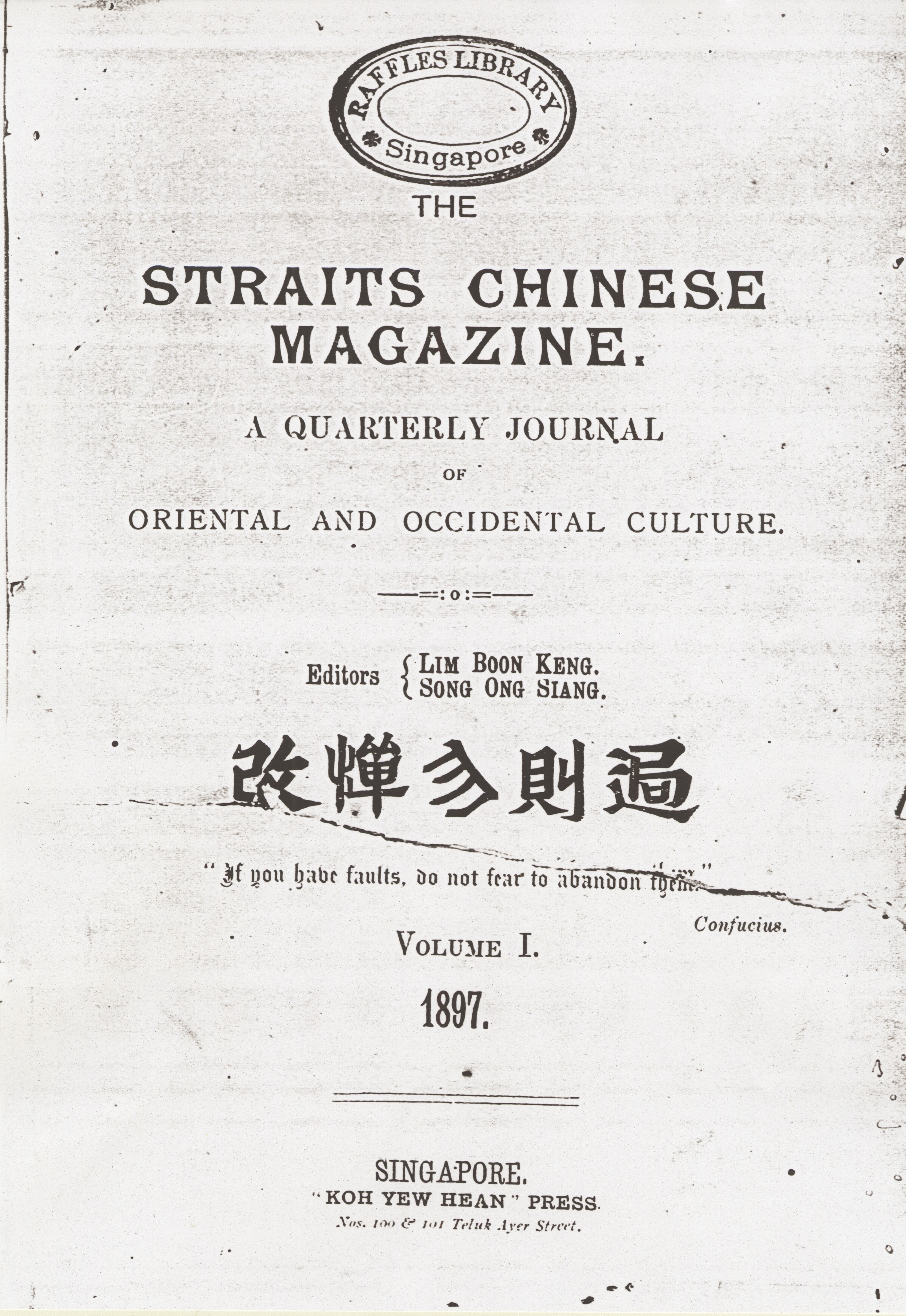

Dr Lim and Song Ong Siang started the Straits Chinese Magazine, and served as its editors. This quarterly magazine ran for 11 years from 1897 to 1907. Dr Lim contributed no less than 20 articles to the magazine, mainly covering health issues, his ideas on various social reforms, and Confucianism.

In 1899, he started writing about social reforms, covering the question of whether Chinese should keep their queues, dress and costume, the education of children, religion, filial piety and funeral rites. His call to Chinese men A copy of this is available in the National Library to remove the queue (also known as the towchang), in particular, caused an uproar.2 Even in his later years, he continued to stand by his conviction that long hair was unnecessary, unhygienic and disgraceful to the Chinese. It represented an era of Subjugation (Morgan, 1956). He also condemned the smoking of opium in the Chinese community and wrote numerous articles in support of Confucian practices. Some of the concepts that he brought up included Confucian cosmogony and theism; the basis of Confucian ethics; the Confucian doctrine of brotherly love; the status of women under a Confucian regime; Confucian code of conjugal harmony and Confucian ethics of friendship.

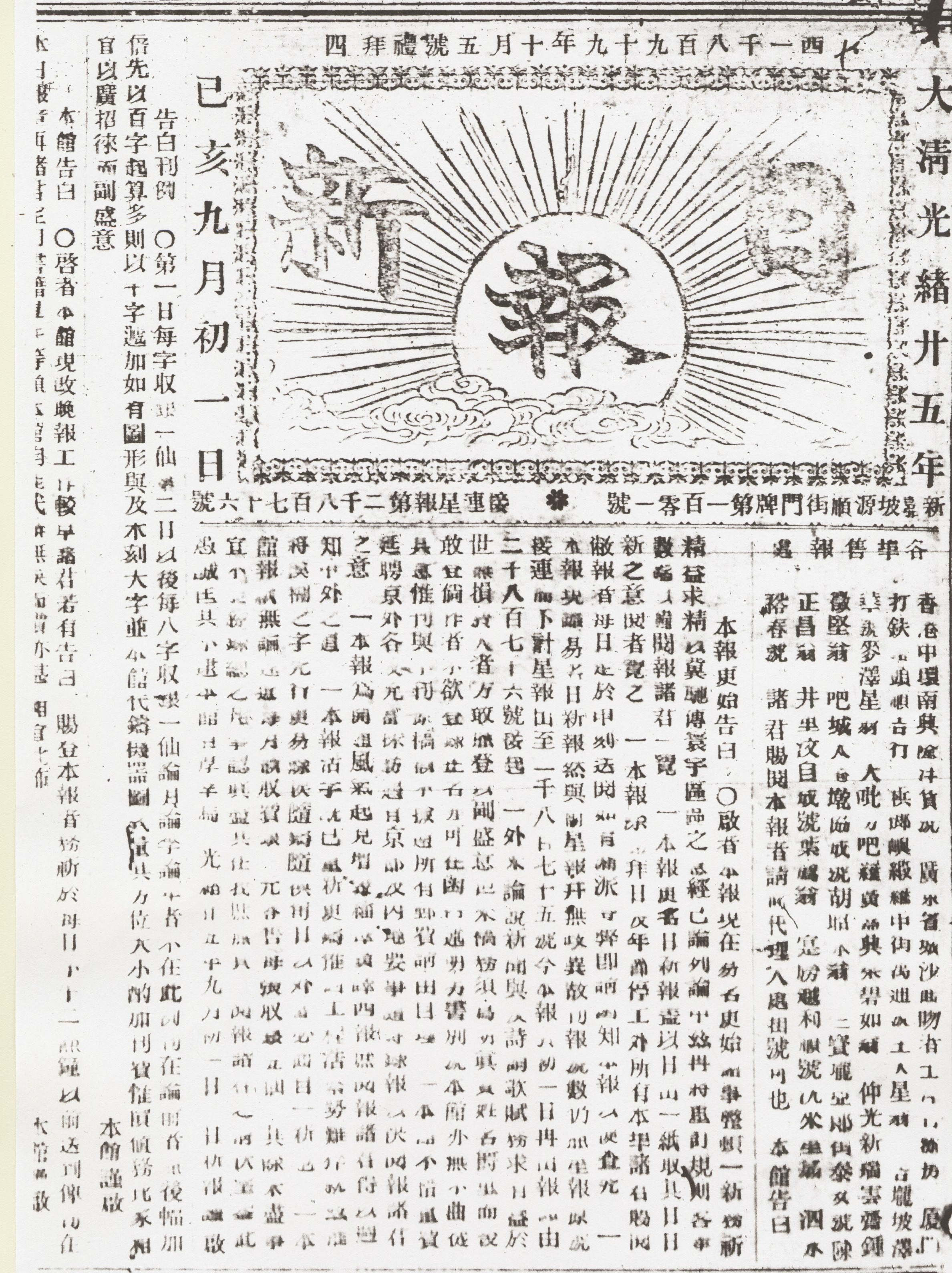

Dr Lim and his father-in-law, Wong Nai Siong, also bought over a Chinese newspaper, Xing Bao and renamed it Ri Xin Bao. Once again, this paper became a medium for him to reach out to the Chinese community. In order to broaden the horizon of this community, he included international news and reports on science and technology in the Western countries. Unfortunately, the paper ran for only two years because of financial problems (1985).

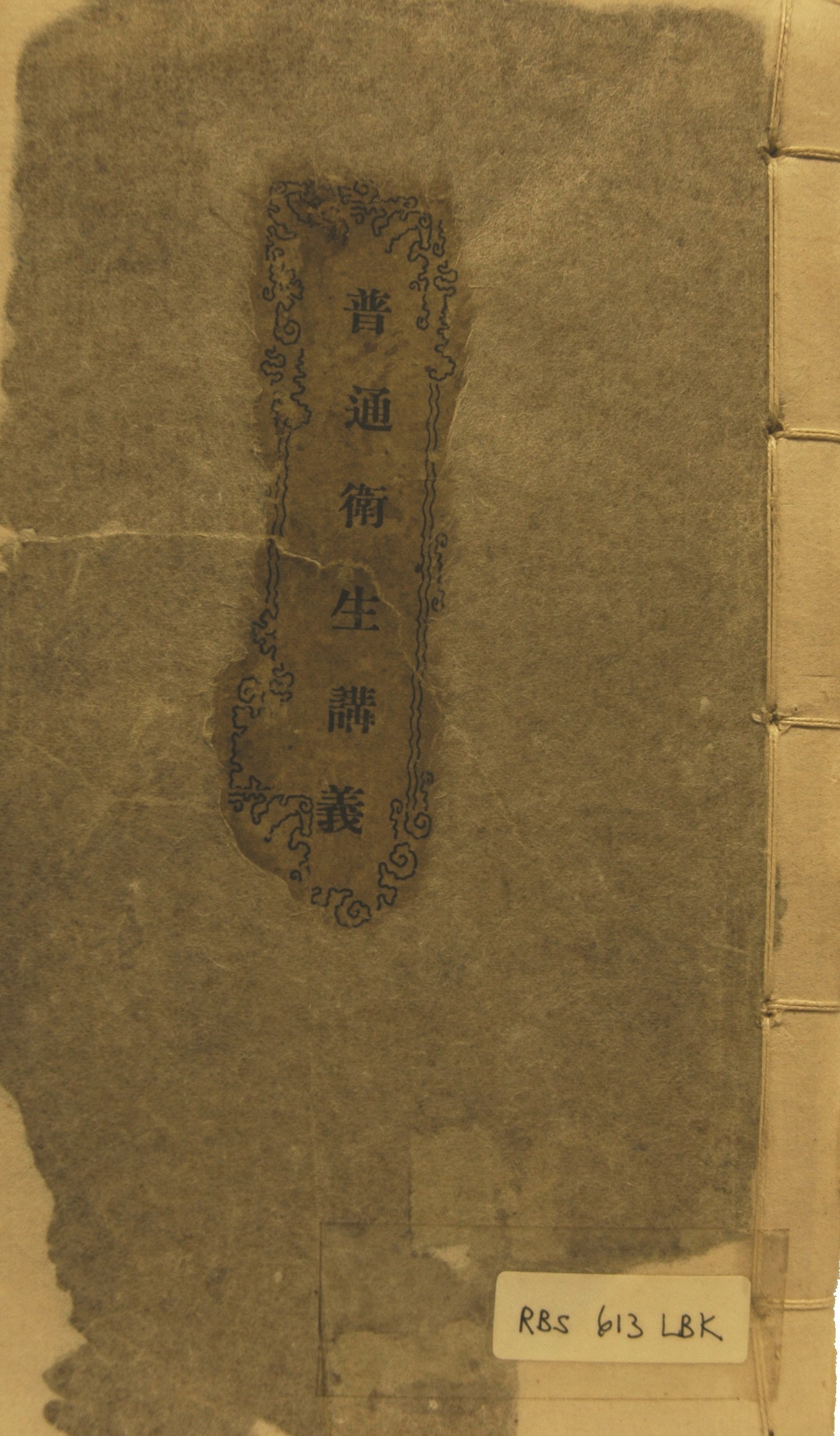

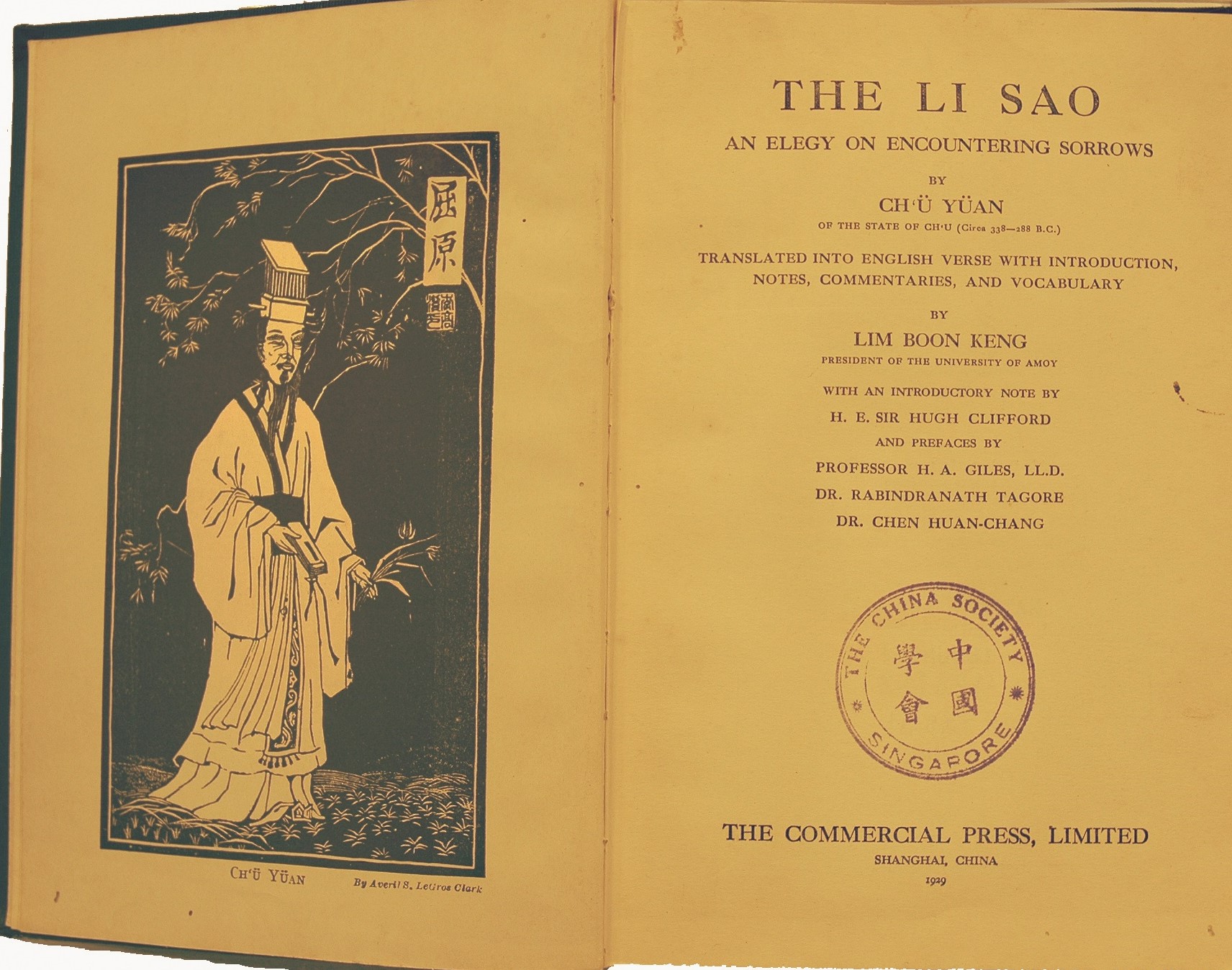

Being a prolific writer, Dr Lim wrote many books and did some translations or Elements of Popular Hygiene (1911) and published in 1911 or Principles of Confucianism (1914) were two examples of his Chinese works. Examples of his English publications include The Chinese Crisis from Within (1901), The Great War from the Confucian Point of View, and Kindred Topics: Being Lectures Delivered during 1914–1917 (1917), Tragedies of Eastern Life: An Introduction to the Problems of Social Psychology (1927), and The Li Sao: An Elegy on Encountering Sorrows (1929).

Outstanding Pioneer

Dr Lim received several eminent awards in his life. In 1918, he received the Order of the British Empire in recognition of his public service. He was also decorated with the Commander Crown of Italy, and received the Albertus Medal of Saxony. The Qing Government awarded him the Wen Hu Jiang and the Jia He Jiang. In 1919, he received an honorary Doctor of Laws from the Hong Kong University. In 1930, he was made an F.R.C.S. (London).

After the war, in contrast to his illustrious pre-World War II years, Dr Lim lived his last 12 years as a recluse.

The Straits Times interviewed him twice. Once was in 1948, at his 80th birthday, when he was quoted as “The Sage of Singapore”. Asked for his recipe for a ripe, old age, he replied, “I have no recipes or formulas. The main thing I would say to you, if you want to go on living, is: Don’t worry, and don’t cry over split milk” (Ferroa, 1948).

The other interview was done in 1956, at his 88th birthday. It was reported that he spent most of his time reading books and newspapers. He regarded himself as a graduate in the art of living who had majored in tolerance (Morgan, 1956). As Singapore society was then being rocked by riots and strikes, Dr Lim took the opportunity to urge the Chinese community to:

Go forward in friendship with other communities towards

the common goal of a unified interracial family.

Accept and adjust yourselves to change in the interest

of all.

Grasp every opportunity for education because ignorance

is a sin (Morgan, 1956).

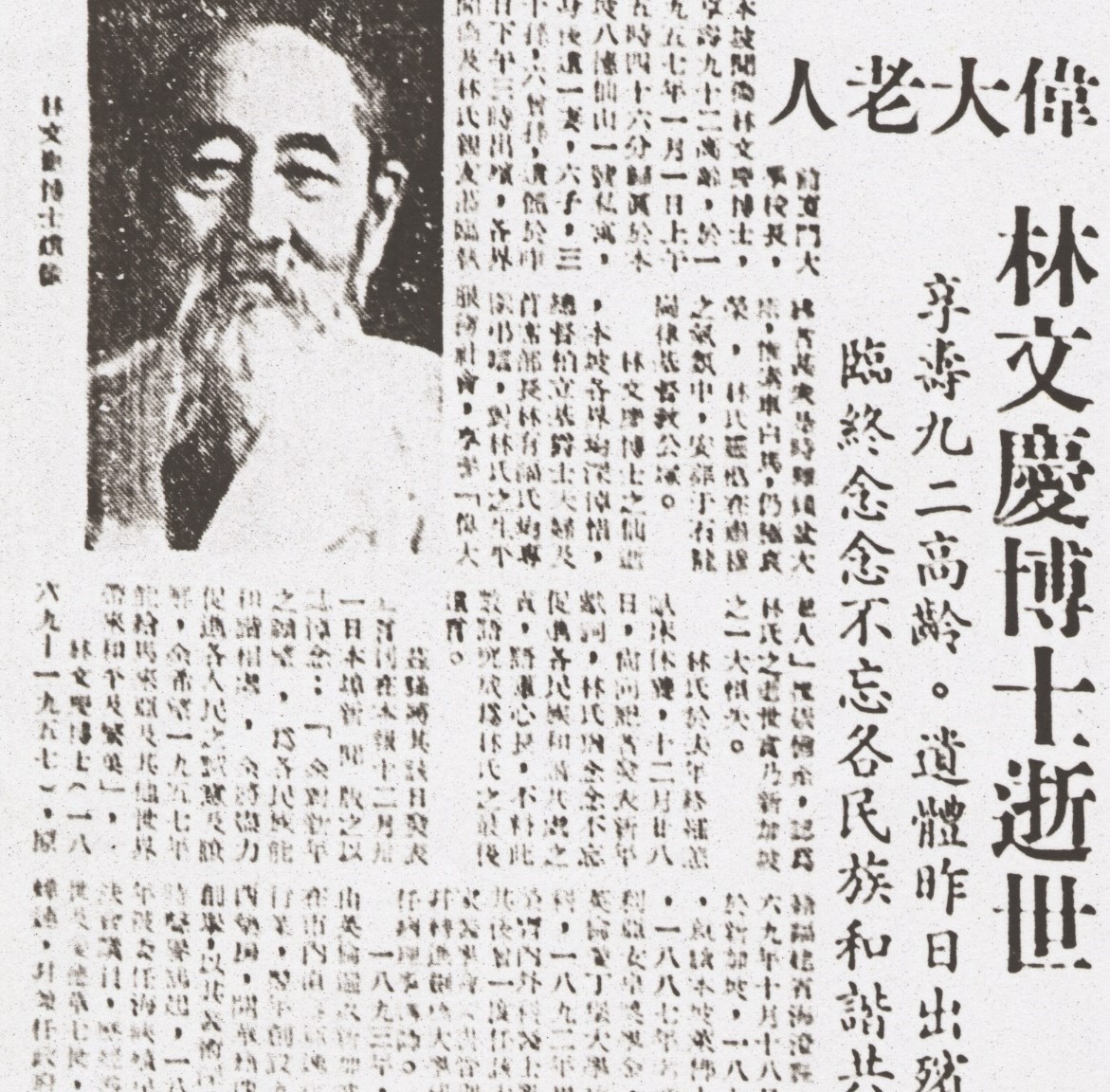

On 1 Jan 1957, Dr Lim Boon Keng passed away peacefully at 5.46am. His passing marked the end of a man who gave selflessly towards improving the Chinese community during colonial times.

Book Launch (24 January 2007)

Conference: Lim Boon Keng and the Straits Chinese: There will be a book launch of the republished edition of Dr Lim Boon Keng’s seminal work, The Chinese Crisis from Within.

Musical (24 January 2007)

A half-hour programme of songs from the musical One Voice by Stella Kon will be presented on the day of the book launch. It was inspired by the life and times of Dr Lim Boon Keng. Stella Kon will introduce the musical, which she wrote in tribute to her great-grandfather, Dr Lim.

Exhibition: Lim Boon Keng: A Life to Remember (24 January 2007 - 18 March 2007)

This exhibition will feature the multi-faceted life of Dr Lim, and present issues on the identity, ideals and social problems of Singapore and Chinese society during his lifetime.

Conference: Lim Boon Keng and the Straits Chinese: A Historical Reappraisal (27 January 2007)

At a full-day conference held at the National Library, academics will present their research on Dr Lim and the Straits Chinese. Associate Professor Philip Holden will start with a biographical account of the pioneer, and this will be followed by two sessions on Dr Lim and his times, as well as issues on Straits Chinese history. Associate Professor Lee Guan Kin will also deliver a public lecture in Mandarin, covering “The Boon Keng Pavilion at Xiamen University: History Recovered, Nanyang Link Reconnected”. There will be a simultaneous translation in English for her lecture.

Ang Seow Leng is a Senior Reference Librarian at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library.

Ang Seow Leng is a Senior Reference Librarian at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library.REFERENCES

“Chinese Christian Association,” Straits Chinese Magazine 2, no. 7 (September1989): 124. (Call no. RRARE 959.5 STR; microfilm NL267)

Huang Yihua 黄溢华, “林文庆” [Lim Boon Keng] in Yi he xuan jiu shi zhou nian ji nian te kan, 1895–1985 怡和轩九十周年纪念特刊, 1895–1985 [Nineteenth anniversay of Ee Hoe Hian Club, 1895–1985] ([Xinjiapo] [新加坡]: Da shui niu chu ban ji gou 大水牛出版机构, 1985). (Call no. Chinese RSING 369.25957 YHX)

Khor Eng Hee, The Public Life of Dr. Lim Boon Keng (Singapore: University of Malaya, 1958). (Call no. RCLOS 361.924 LIM.K)

Kiong Chin Eng, “The Teaching of Kuan Hua in Singapore,” Straits Chinese Magazine 11, no. 2 (1907): 105–8. (Call no. RRARE 959.5 STR; microfilm NL268)

Li Yuanjin 李元瑾, Dong xi wen hua de zhuang ji yu xin hua zhi shi fen zi de san zhong hui ying: Qiu Shuyuan, Lin Wenqing, Song Wangxiang de bi jiao yan jiu 东西文化的撞击与新华知识分子的三种回应 : 邱菽园、林文庆、宋旺相的比较研究 [The impact of Eastern and Western cultures and the three responses of Xinhua intellectuals: A comparative study of Qiu Shuyuan, Lin Wenqing, and Song Wangxiang] (Xinjiapo 新加坡: Xinjiapo guo li da xue Zhong wen xi, Ba fang wen hua qi ye 新加坡国立大学中文系, 八方文化企业, 2001). (Call no. Chinese RSING 305.552095957 LYJ)

Lim, Boon Keng, “Our Enemies,” Straits Chinese Magazine 1, no. 2 (1897): 52–58. (Call no. RRARE 959.5 STR; microfilm NL267)

Llyod Morgan, “Singapore’s Grand Old Man (88 Tomorrow) Calls for Tolerance in This Age of Change,” Straits Times, 17 October 1956, 2. (From NewspaperSG)

Ooi Yu-Lin, Pieces of Jade and Gold an Anecdotal History of the Singapore Chinese Girls’ School 1899–1999 (Singapore: Singapore Chinese Girls’ School, 1999). (Call no. RSING 373.5957 OOI)

Png Poh Seng, “The Kuomintang in Malaya,” Journal of Southeast Asian History 2, no. 1 (March 1961): 1–32. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Roy Ferroa, “The Sage of Singapore,” Straits Times, 22 October 1948, 4. (From NewspaperSG)

“Singapore’s Grand Old Man Dies,” Straits Times, 2 January 1957, 1. (From NewspaperSG)

Song, Ong Siang, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1984). (Call no. RSING 959.57 SON)

Tan Yeok Seong, History of the Formation of the Oversea Chinese Association and the Extortion by J.M.A. of $50,000,000 Military Contribution From the Chinese in Malaya (Singapore: Nanyang Book Co., 1947). (Call no. RDTYS 940.53109595 TAN)

Ye Guan Shi 叶观仕, Ma xin bao ren lu (1806–2000) 马新报人录 (1806–2000) [Who’s who in the press, Malaysia & Singapore (1806–2000)] ([Place of publication not identified] [S.l.]: Ming ren chu ban she 名人出版社, 1999), 27. (Call no. Chinese RSING q 070.922595 WHO)