Photo Studios and Photography During the Japanese Occupation

During the Japanese Occupation, local photographers worked under challenging conditions.

By Zhuang Wubin

The Japanese Occupation of Singapore that began in February 1942 and ended in September 1945 was a harrowing time for Singapore. The months leading up to the British surrender were marked by almost constant bombing by the Japanese. The initial weeks of Japanese military rule were particularly brutal, especially as they attempted to eliminate anti-Japanese elements within Singapore. However, a semblance of normalcy eventually returned as people attempted to rebuild their lives while waiting for better times ahead.

The demand for certain photographic services resumed. Some of the prewar photo studios that had serviced people wanting to mark significant events in their lives were able to reopen their businesses. It was not business as usual though. The studios had a significant new clientele, which were the military personnel and residents connected to the Japanese administration. The studios also had to be creative, as items like film were in short supply.

Chinese Photo Studios

During the period when Singapore was known as Syonan-to (“Light of the South”; 昭南島), there were at least two types of Chinese-run photo studios. There were those established before the war, some of which resumed operations during the Occupation period. There were also studios that opened during the Occupation years.

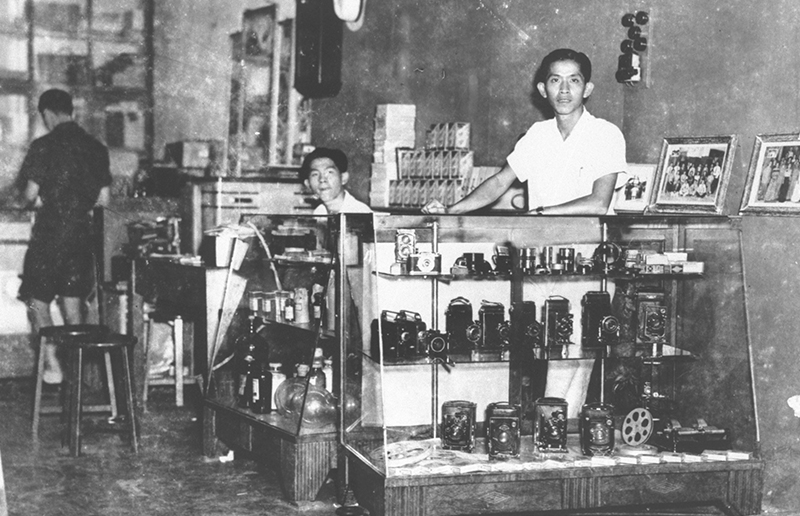

Daguerre Studio fell into the first category. It was set up in 1931 by Lim Ming Joon (circa 1904–91, b. Hainan). Two Japanese photographers had helped him pick up the trade and establish his business. In the latter half of 1941, his nephew Lim Tow Tuan (b. 1916, Hainan) joined him as an unpaid apprentice.1

The Japanese invasion began in December 1941 and Daguerre Studio on Middle Road was among the many buildings in the city that suffered damage from air raids. A bomb fell behind the studio, shattering the glass panels on the roof.2 “The Japanese soldiers had already reached Johor Bahru. [We] decided to move all our photographic equipment to my uncle’s wooden hut at the 6th milestone of Hougang, in a village of coconut trees. [We] had bought some rice and food, which we also moved there,” recalled Lim Tow Tuan. “I stayed with my uncle in the village.”3

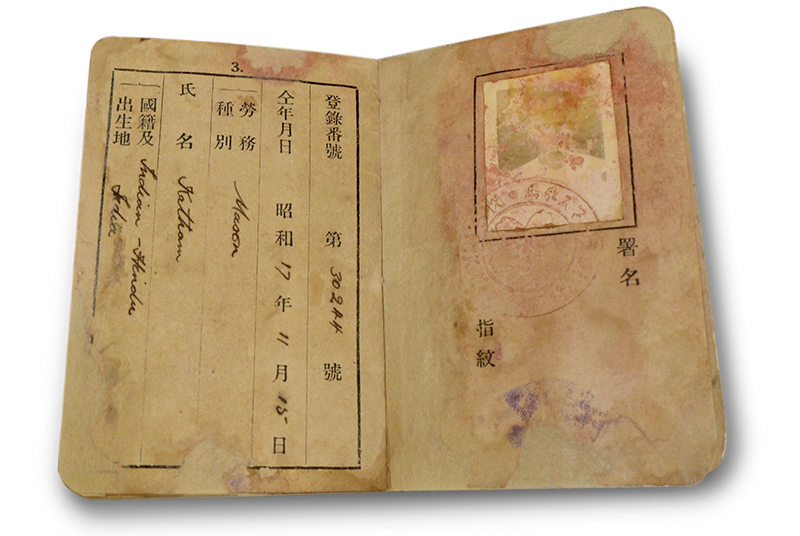

A few weeks after the Japanese had established control over Singapore, Lim Ming Joon and his nephew decided to reopen Daguerre. They walked from Hougang to Middle Road and found that their studio had not been badly damaged, although the shattered glass panels meant that it was not possible to operate on rainy days. Eventually, they began to get a few customers as people trickled in to take identification photographs.4 One of the Japanese photographers, who had previously helped Lim, returned to Singapore and helped Lim apply to the Labour Control Office for Daguerre Studio to be one of the officially appointed photographers on the island.5 That provided a boost to his business.

By early October 1942, Daguerre Studio was listed in the Syonan Times – the newspaper that replaced the Straits Times during the Occupation years – as an officially appointed photo studio.6 With the appointment, Lim believed that those associated with the Japanese authorities were more likely to patronise his studio.7 After the appointment, Japanese customers, including soldiers, became more polite to him. They would bow and greet Lim before entering the premises. In general, he found that the Japanese were respectful towards photographers.8

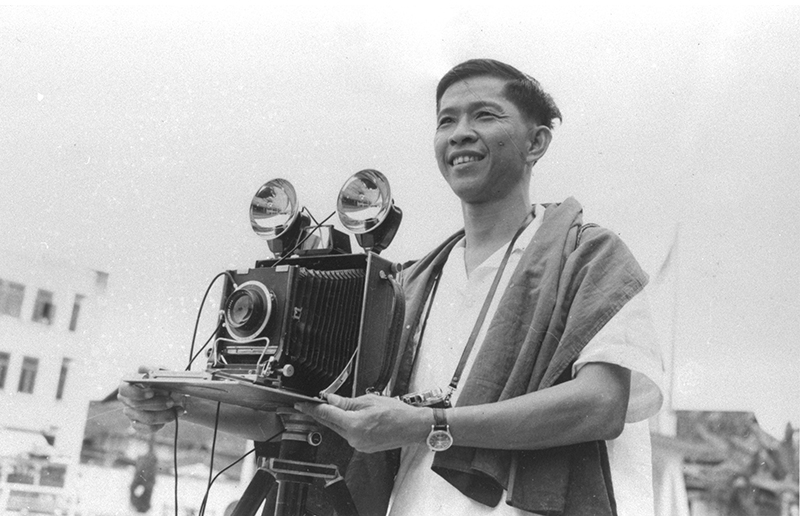

Tai Tong Ah Studio (大东亚) was one of those that opened during the Occupation years. It was established in October 1942 by the photographer Chew Kong (b. circa 1905, Taishan, China). Chew had already been contributing his photographs to various newspapers before the war. In the final days leading to the fall of Singapore, he tried to join the Singapore Overseas Chinese Anti-Japanese Volunteer Army (also known as Dalforce), which was hastily established in December 1941.

Some months after surviving Operation Sook Ching,9 Chew joined an Indian-owned studio at 78 Bras Basah Road (most likely Ukken’s Studio).10 When the owner was conscripted to work in the Japanese army, he sold the business to Chew cheaply. Chew then renamed the studio Tai Tong Ah. Chew did not bother applying to be an officially appointed photographer because he already had sufficient work and did not believe that the appointment would help his business.11

The Challenges of Working During the Japanese Occupation

Photographers working during the Japanese Occupation faced a number of challenges. During this period, every single photograph printed by the photo studios had to be checked by the dreaded Kempeitai, the Japanese Imperial Army’s military police. The photos had to be brought to the YMCA building on Orchard Road for vetting. Images concerning the private affairs between a man and a woman were prohibited along with photographs of soldiers from other countries.12

To avoid the hassle of being questioned by the Kempeitai, Chew would usually decline to develop the negatives that some random customers brought to the studio. “I would claim that I had run out of chemicals,” he said.13

During the Occupation, lack of film was a major issue. Before the war, Lim Ming Joon of Daguerre had the foresight to stock up on paper, film and chemicals. When Daguerre resumed business during the Occupation, he had his stock to fall back on. He eventually ran out of negatives though and at one point, Lim used film intended for motion pictures to produce identification photographs for his customers.14

Chew, on his part, used expired film left behind by the Royal Air Force. The Japanese had actually discarded the film, which allowed some soldiers to steal the stock and sell it to operators like Chew. However, it still required a level of ingenuity by Chew to make the expired materials yield reasonable results.15

It was sometimes possible to buy fresh film intended for military use, which had been smuggled out by soldiers. Higher-ranking service personnel could obtain fresh film for their own use and if they had a few frames left, the more generous ones would give the remainder to Chew. Occasionally, some Japanese merchants were able to import 120 mm film. If Chew could purchase two or three rolls, he would cut the film into smaller pieces so that these could last him for a longer time.16

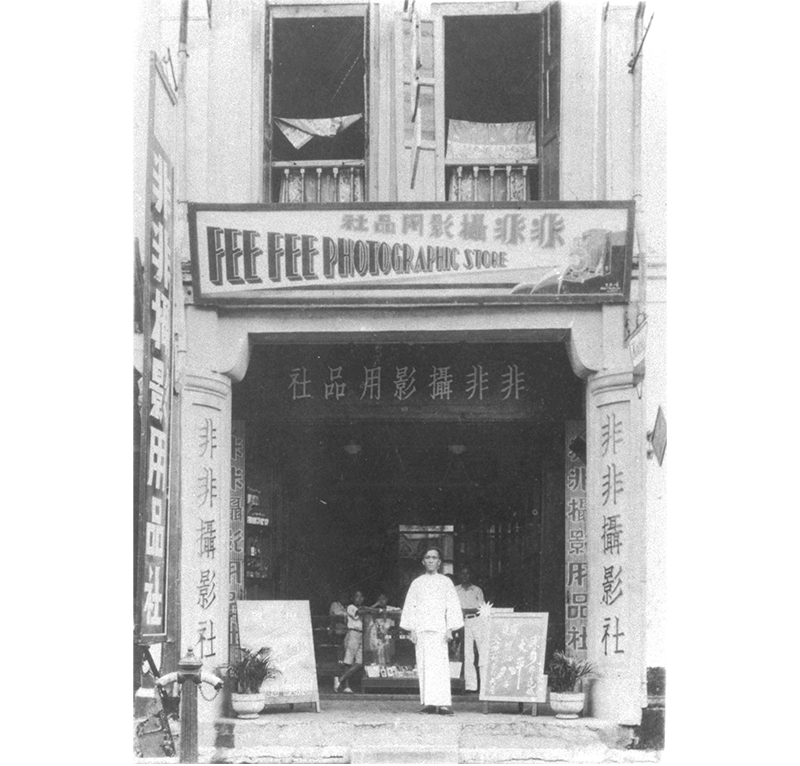

Chu Sui Mang (b. 1922–96, Singapore), who ran Fee Fee Photographic Store (it was not a photo studio but provided photographic supplies and services) at 160 Cross Street, survived two encounters with the Kempeitai. Chu reopened Fee Fee after the Occupation began as he still had some photo supplies left. However, in the subsequent months, Chu was arrested twice on trumped-up charges. “My hand became crooked,” Chu recalled the torture that he had suffered. “The beating made me deaf in the ear.”17 He was eventually allowed to go home but had to report to the special police whenever they needed him to develop and print photographs. Chu was only given meals and was not paid for his work. This lasted for some months.18

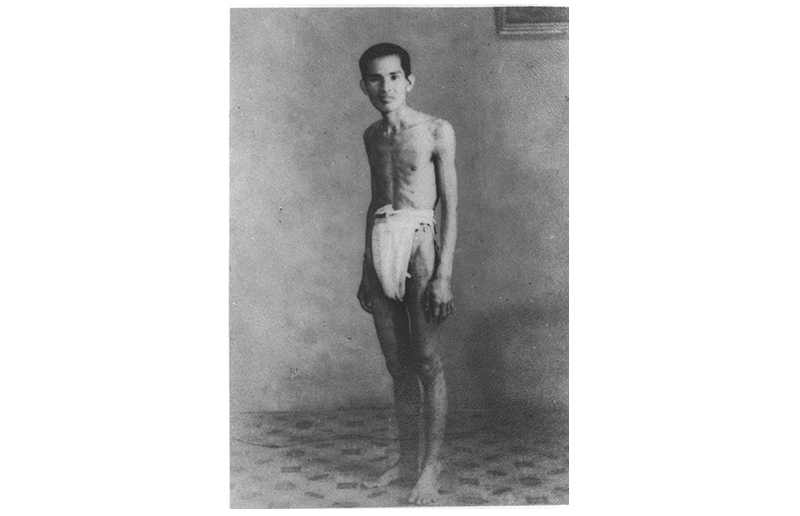

Another person who survived a run-in with the Kempeitai was Lim Tow Tuan, the nephew of the owner of Daguerre. Someone named Lim as a member of the anti-Japanese resistance and he was picked up by the Kempeitai around September 1944 and detained at its centre on Smith Street. The interrogation began two months later, and Lim was subjected to daily beatings and torture to get him to admit that he was involved in the resistance. “After more than a month of waterboarding, I had a dream at night. Someone patted me and told me to admit the charges, or else I would be beaten to death,” Lim recalled. The following day, Lim admitted to the false accusation. Upon hearing his confession, the attitude of the interrogating officer changed immediately. The officer asked if he was hurt and whether he wanted coffee or tea, Lim recalled.19

The whole ordeal of detention and interrogation lasted six months.20 After confessing to the charges in March 1945, Lim was sentenced to twelve-and-a-half years of imprisonment and sent to Outram Prison.21 He was released when the Japanese surrendered in August that year.

Customers of the Photo Studios

According to the authors of Singapore: A Biography, the Japanese Occupation marked the “birth of the territory’s first bureaucratically obsessed state”, which “undertook the first ever registration of Singapore and Malaya’s entire population”.22 The officially appointed studios were tasked to produce these photographs.

For Daguerre and Tai Tong Ah, service personnel and immigrants connected to the Japanese authorities also made up an important part of their clientele. Not long after the start of the Occupation, an officer asked Lim Ming Joon of Daguerre to accompany him to Bukit Timah. The officer believed that his friend had fallen in battle in the area and wanted to take a photograph of his final resting place to send back to Japan. “After failing to find his friend’s remains, the officer poured an offering of alcohol into the stream and muttered a few words in tears,” Lim said.23

A more common request was by military personnel who wanted group photographs at their barracks so that they could send the prints home.24 “Japanese and Taiwanese personnel were especially enamoured with taking portraits in military attire,” Chew of Tai Tong Ah recalled. Special occasions, including the birthday of a superior, also warranted photo-taking.25

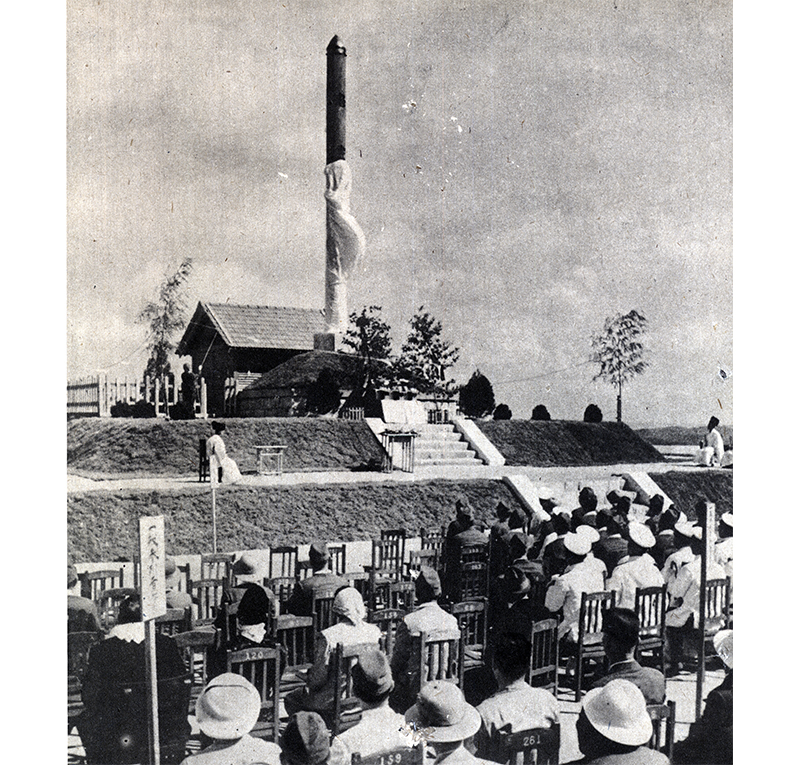

Photographers were sometimes asked to accompany military personnel as they went sightseeing in their newly conquered territories. Lim Ming Joon was taken on a leisure trip to Johor Bahru by a Japanese officer. One of the stops was the royal palace, where Lim took a portrait of the officer for commemoration.26 In Singapore, Chew accompanied different groups of soldiers to Haw Par Villa and Syonan Jinja.27 Located near MacRitchie Reservoir, Syonan Jinja was a Shinto shrine that commemorated the conquest of Singapore and served to instil patriotism towards the Japanese emperor.28

Among the people whom Chew photographed were women who worked in the Japanese sex industry. Once, he was asked to go to a big house in Pasir Panjang which was full of women asking him for group photographs. Most of the women were Japanese, but Chew believed there might be Taiwanese and Korean women among them. “Some of them also enjoyed having their individual portraits taken,” he recalled.29

During the Occupation, civilian residents in Singapore tried, as best as they could, to carry on with their lives. People continued to work, to live and to get married. As a result, there was still a modest demand for wedding portraits. The demand for photography was not entirely frivolous. Apart from marking the occasion, the photographs also served as visual evidence that a woman was married, thus conferring some protection from the Japanese. Chew recalled, in particular, doing the wedding portraits of Chinese women who married Japanese men. He remembered photographing around six such couples. “From the way they spoke Chinese, I think the women were from the educated class,” Chew said.30

Working for the Japanese

Alongside the photo studios that managed to remain open, there were a few photographers who were asked to work for the Japanese. The photographer David Ng Shin Chong (b. 1919, Singapore) had apprenticed at Natural Studio before the war. During the Occupation period, he worked for the Japanese in Cathay Building, which housed the Japanese Military Propaganda Department, the Military Information Bureau and the Japanese Broadcasting Department.31 His job was to develop film while his colleague, Cai, did the printing and enlargement. For his work, Ng was paid a small salary, but more crucially, he was given rations – rice, sugar, salt and, once a year, some coarse fabric that he would use to make clothes.32

Most of the photographs that Ng and Cai produced were for propaganda purposes. Ng remembered two incidents vividly. The first was a set of photographs taken after the Japanese had shot down an American B-29 bomber. Back at Cathay Building, Ng developed the negatives and in the frames, he saw an American sergeant who was still alive but tied to a tree. There were also many images of the plane’s wreckage. The resulting photographs were displayed at the Great World amusement park and subsequently sent to Japan.33

The other memorable incident was when Ng and Cai were tasked to take photographs as Japanese and Indian troops charged up a hill in Sembawang in a mock attack while carrying the flag of the Provisional Government of Azad Hind (Free India), the Japanese-supported effort to use Indian nationalists against the British in India.34 Shortly after, Ng’s photograph appeared on the cover of a local magazine, which reported that the forces had reached Burma and secured victory. Their photographs were also printed in a photo spread in the magazine. Relating the incident more than four decades later, Ng let out a curse and chuckled: “What a joke!”35

Freedom At Last

Towards the end of 1944, Lim Ming Joon heard rumours that the Allied forces were planning to retake Singapore. Worried that fierce fighting would break out, Lim relocated his family to Alor Gajah in Melaka where they lived there for eight months until the Japanese surrender. A friend helped to look after Daguerre Studio, though by then there were very few customers.36

His nephew, Lim Tow Tuan, who had spent much of the last months of the Occupation in Outram Prison, was released after Japan surrendered. One of the first things he did was to return to the studio to take a self-portrait to mark his suffering and eventual release.37 Lim also changed his name as he felt that his name had been sullied by the imprisonment. With people who knew him very well, he used Lim Tow Tuan. For mere acquaintances, he went by the name Lim Seng.38

According to David Ng, those who worked at Cathay Building were among the first to learn about the surrender. His Japanese superior conveyed the announcement and asked Ng what his plans were. When Ng told him that he would continue working as a photographer, his superior promptly gave Ng and Cai some of the photo supplies and equipment, including chemicals, paper, enlarger and a few cameras.

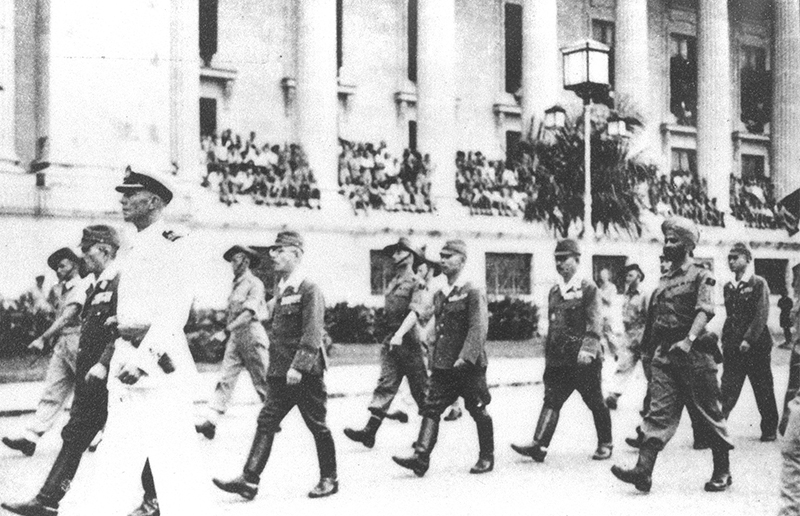

Ng used these items well. During the surrender ceremony held at the Municipal Building in Singapore on 12 September 1945, Ng went there with his camera. As he was not a press photographer, Ng could not enter the building so he took a few photographs from the Padang, with the intention of commemorating the occasion. Ng quickly realised there was a demand for these photographs and he made a small fortune from selling the images.39 Later that year, Ng rented a space in a shop beside Liberty Cabaret on North Bridge Road and established David Photo.40

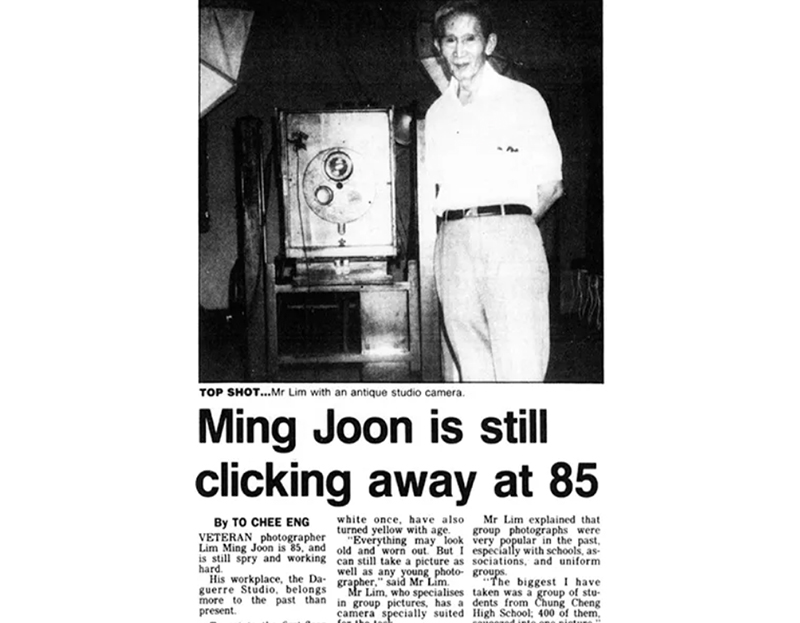

After the war, Lim Ming Joon continued to run Daguerre Studio on Middle Road. Over time, he became known for taking commemorative group portraits for schools, guilds and unions. He remained active professionally until his death in 1991.41

As for Tai Tong Ah, Chew Kong closed it after the war as he preferred to work freelance, taking on photo commissions and contributing images to newspapers.42 However, in May 1949, he opened Kong Photo Studio on Geylang Road.43

With the return of peace to Singapore, Chu Sui Mang rebuilt his business at Fee Fee. Today, his daughters continue to run Fee Fee House of Photographics on a modest scale in Hong Lim Complex.44 It is one of the few remaining photo businesses established locally prewar, which survived the Japanese Occupation and advances in photography.

Zhuang Wubin is a writer, curator and artist. He has a PhD from the University of Westminster (London) and is currently a National Library Digital Fellow. Wubin is interested in photography’s entanglements with modernity, colonialism, nationalism, the Cold War and “Chineseness”.

Zhuang Wubin is a writer, curator and artist. He has a PhD from the University of Westminster (London) and is currently a National Library Digital Fellow. Wubin is interested in photography’s entanglements with modernity, colonialism, nationalism, the Cold War and “Chineseness”.NOTES

-

Zhuang Wubin, “Negotiating Boundaries: Japanese and Chinese Photo Studios in Prewar Singapore,” BiblioAsia 18, no. 2 (September 2022): 27–28. ↩

-

Lim Seng @ Lim Tow Tuan, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 28 December 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 2 of 8, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000089), 16. ↩

-

Lim Seng @ Lim Tow Tuan, oral history interview, 28 December 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 3 of 8, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000089), 17. ↩

-

Lim Seng @ Lim Tow Tuan, oral history interview, 28 December 1983, Reel/Disc 3 of 8, 20–21. ↩

-

Lim Ming Joon, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 14 October 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 3 of 7, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000333), 39–40. ↩

-

“Page 3 Advertisements Column 2,” Syonan Times, 6 October 1942, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lim Ming Joon, oral history interview, 14 October 1983, Reel/Disc 3 of 7, 40. ↩

-

Lim Ming Joon, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 21 October 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 6 of 7, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000333), 75–76, 78. ↩

-

Operation Sook Ching was conducted from 21 February to 4 March 1942 during which Chinese males between the ages of 18 and 50 were summoned to various mass screening centres and those suspected of being anti-Japanese were executed. ↩

-

If Chew Kong’s memory of the address was accurate, the studio was owned by K.J. Ukken and was known as Ukken’s Studio. See “Page 3 Advertisements Column 2,” Syonan Times, 20 October 1942, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chew Kong, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 27 October 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 4 of 9, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000056), 59–61. ↩

-

Chew Kong, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 27 October 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 5 of 9, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000056), 62–64. ↩

-

Chew Kong, oral history interview, 27 October 1983, Reel/Disc 5 of 9, 71–72. ↩

-

Lim Ming Joon, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 14 October 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 4 of 7, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000333), 50–51. ↩

-

Chew Kong, oral history interview, 27 October 1983, Reel/Disc 5 of 9, 67–70. ↩

-

Chew Kong, oral history interview, 27 October 1983, Reel/Disc 5 of 9, 67–70. ↩

-

Chu Sui Mang, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 30 December 1984, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 4, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000518), 8–11; Chu Sui Mang, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 30 December 1984, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 2 of 4, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000518), 18. ↩

-

Chu Sui Mang, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 30 December 1984, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 3 of 4, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000518), 36–39. ↩

-

Lim Seng @ Lim Tow Tuan, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 28 December 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 4 of 8, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000089), 27–35. ↩

-

Lim Seng @ Lim Tow Tuan, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 28 December 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 5 of 8, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000089), 53. ↩

-

Lim Seng @ Lim Tow Tuan, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 28 December 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 6 of 8, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000089), 64, 66. ↩

-

Mark R. Frost and Yu-Mei Balasingamchow, Singapore: A Biography (Singapore: Editions Didier Millet and National Museum of Singapore, 2009), 301. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 FRO-[HIS]) ↩

-

Lim Ming Joon, oral history interview, 14 October 1983, Reel/Disc 4 of 7, 43–44. ↩

-

Lim Ming Joon, oral history interview, 14 October 1983, Reel/Disc 3 of 7, 41–42. ↩

-

Chew Kong, oral history interview, 27 October 1983, Reel/Disc 5 of 9, 62, 64–65. ↩

-

Lim Ming Joon, oral history interview, 21 October 1983, Reel/Disc 6 of 7, 78–79. ↩

-

It is possible that Chew Kong actually meant Syonan Chureito in Bukit Batok, an obelisk dedicated to the Japanese war dead, instead of Syonan Jinja. He could also be referring to both shrines as one. See Chew Kong, oral history interview, 27 October 1983, Reel/Disc 5 of 9, 73. ↩

-

For more information about Syonan Jinja and Chureito, see Kevin Blackburn and Edmund Lim, “The Japanese War Memorials of Singapore: Monuments of Commemoration and Symbols of Japanese Imperial Ideology,” South East Asia Research 7, no. 3 (November 1999): 321–40. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Chew Kong, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 3 November 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 8 of 9, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000056), 115–16. ↩

-

Chew Kong, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 3 November 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 7 of 9, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000056), 95–97. ↩

-

Lim Kay Tong and Yiu Tiong Chai, Cathay: 55 Years of Cinema (Singapore: Landmark Books for Meileen Choo, 1991), 101. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 791.43095957 LIM) ↩

-

David Ng Shin Chong, oral history interview by Ang Siew Ghim, 5 June 1986, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 7 of 13, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000670), 76–78; David Ng Shin Chong, oral history interview by Ang Siew Ghim, 5 June 1986, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 8 of 13, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000670), 82. ↩

-

David Ng Shin Chong, oral history interview, 5 June 1986, Reel/Disc 8 of 13, 88–90. ↩

-

On 21 October 1943, freedom fighter Subhas Chandra Bose (1897–1945) announced the formation of the Provisional Government of Azad Hind (Free India) in Singapore. With the support of the Japanese imperialists, Bose proclaimed the start of war to liberate India from British colonialism. He raised funds for the movement and recruited people for its army, which made a push for India, via the Myanmar border, in April 1944. ↩

-

David Ng Shin Chong, oral history interview, 5 June 1986, Reel/Disc 8 of 13, 82–85. Veteran journalist Han Tan Juan reported a different version of the incident. See 韩山元 Han Tan Juan, “Jingtou xia de lishi” 镜头下的历史 [History under the lens], 联合晚报 Lianhe Wanbao, 1 March 1986, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lim Ming Joon, oral history interview, 21 October 1983, Reel/Disc 6 of 7, 84, 88–89. ↩

-

Lim Seng @ Lim Tow Tuan, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 5 January 1984, transcript and MP3, Reel/Disc 7 of 8, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000089), 77–82. ↩

-

Lim Seng @ Lim Tow Tuan, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 5 January 1984, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 8 of 8, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000089), 90. ↩

-

David Ng Shin Chong, oral history interview by Ang Siew Ghim, 5 June 1986, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 9 of 13, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000670), 101–04. ↩

-

David Ng Shin Chong, oral history interview by Ang Siew Ghim, 11 June 1986, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 10 of 13, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000670), 107. ↩

-

Zhuang, “Negotiating Boundaries: Japanese and Chinese Photo Studios in Prewar Singapore,” 28. ↩

-

Chew Kong, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 3 November 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 9 of 9, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000056), 129. ↩

-

Chew Kong, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 17 November 1983, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 5 of 6, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000066), 15:57. ↩

-

Personal correspondence with the daughters of Chu Sui Mang, 23 March 2022. ↩