The Other Men Who Surrendered Singapore

Arthur E. Percival should not have been made the convenient scapegoat for the fall of Singapore on 15 February 1942. Eleven other men had taken the decision with him to surrender Singapore to the Japanese.

By Phan Ming Yen

Decades after the surrender of Allied forces to the Japanese on 15 February 1942, much of the blame for the fall of Singapore remains associated with Lieutenant-General Arthur E. Percival, General Officer Commanding Malaya. As military historian Clifford Kinvig noted, Percival was not merely associated with the defeat but “he seemed to some commentators to bear a large responsibility for it”.1

While Percival, as the commander in charge of Malaya, was ultimately responsible for making the decision, that decision to surrender was not made alone. On that fateful day, the surrender was decided by Percival in consultation with 11 other men.

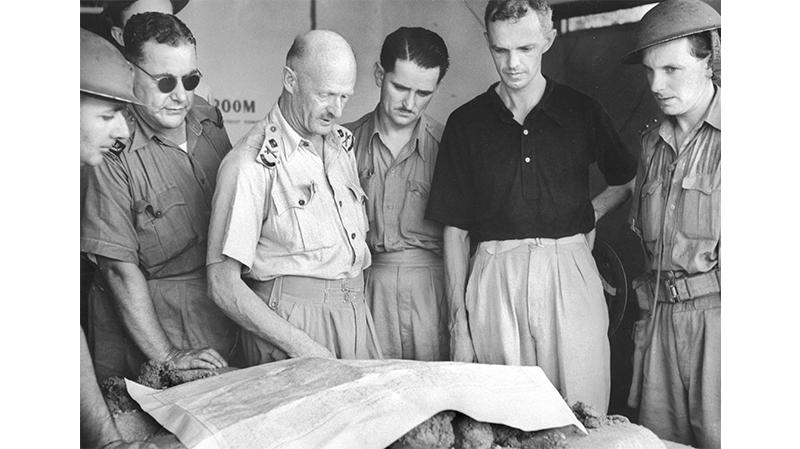

On the morning of the 15th, Percival had called for a meeting in the Battlebox, the underground bunker at Fort Canning, which had served as his headquarters in the last days of the Malayan Campaign. The aim of the meeting was to update the key commanders of the dire situation facing Singapore and to decide on the next course of action.

The war in Malaya had begun with troops of the Japanese 25th Army landing in Kota Bahru in northern Malaya, and Singora and Patani in southern Thailand on 8 December 1941. On the same day, Japanese planes dropped the first bombs on Singapore, killing 61 and injuring 133 people. Two months later, on 8 February 1942, the first Japanese troops landed in Singapore via the northwestern coastline of the island.2

Now, after a week of intense fighting and bombardment, the battle front had been reduced to a semi-circle about three miles from Singapore’s city centre.3 The island had less than 24 hours’ worth of water left, and food and ammunition reserves were running desperately low.4 Naval power had been lost with the sinking of the HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse off the coast of Kuantan on 10 December 1941, while Royal Air Force (RAF) planes had been outclassed by Japanese aircraft.5 On 9 February 1942, all RAF aircraft were withdrawn to the former Netherlands East Indies.

Among the other 11 men huddled together in the same room as Percival, three were senior officers who, according to Percival’s minutes of the meeting, had asserted their views when opinion was sought for the next course of action. They were Lieutenant-General Henry Gordon Bennett, Major-General Frank Keith Simmons and Lieutenant-General Lewis Macclesfield Heath.

Bennett (1887–1962) was Commander of the 8th Division of the Australian Imperial Force and had been assigned the defence of Johor and Melaka. In 1944, he published his account of the Malayan Campaign in a book titled Why Singapore Fell.6 He had also been called “Australia’s most controversial Second World War Commander”. That was because, among other things, following the surrender, Bennett handed over command of his division and left Singapore, supposedly to “pass on his knowledge about how to fight the Japanese”.7

Simmons (1888–1952) was Commander of the Singapore Fortress and responsible for the defence of Singapore, the adjoining islands and the eastern area of Johor. He was the subject of a biography, The Story of Major General F.K. Simmons, CEB, MVO, MC, a Man Among Men, by Percival. In Percival’s eyes, Simmons had a “particularly tactful and courteous manner which was an undoubted asset in his dealings with the civilians of Singapore. He worked unceasingly for the welfare of the troops in that city”.8

Heath (1885–1954) commanded the III Indian Corps from 1941 to 1942 as part of the Malaya Command and had been entrusted with defending northern Malaya. Before his arrival in Malaya, he had gained success as the General Officer Commanding the 5th Indian Infantry Division in the East African Campaign where he planned and executed an assault on the Italian Army at the Battle of Keren in Eritrea in March 1941. In Heath’s obituary, the Straits Times noted that he had been a “soldier whose tactics have been praised by his superiors” and he had served with “distinction in many frontier incidents”.9

In Percival’s notes of the meeting, Heath had argued that “there is only one possible course to adopt” and that was to do what Percival ought to have done two days ago, “namely to surrender immediately”. Heath added that the defenders could not “resist another determined Japanese attack and that to sacrifice countless lives by a failure to appreciate the true situation would be an act of extreme folly”.10 Bennett agreed with Heath and dismissed Percival’s proposal for a counterattack. When Percival sought the opinion of others, Simmons was recorded to have said that he was “reluctant to surrender”, but could see no other alternative.11

The rest, according to Percival, “either remained silent or expressed their concurrence” with Simmons. Major Cyril Hew Dalrymple Wild, Heath’s General Staff Officer, recalled in his own notes that the “decision to ask for terms was taken without a dissentient voice”.12

While the spotlight has typically fallen on Percival, Heath, Bennett and Simmons as the most senior officers in the room, the remaining eight men were also part of the decision-making process. They were Major Cyril Hew Dalrymple Wild,13 Brigadier Thomas Kennedy Newbigging, Brigadier-General Kenneth Sanderson Torrance, Brigadier Alec Warren Greenlaw Wildey, Director-General Ivan Simson, Inspector-General Arthur Harold Dickinson, Brigadier Eric Whitlock Goodman and Brigadier Hubert Francis Lucas.

Their reported silence and concurrence can perhaps be understood – within present-day management discourse – as “acquiescent silence”. This is the silence of individuals who “accept the prevailing circumstances and who are not inclined to speak, participate or spend effort to change current status”, or they are of the opinion that “it is pointless and unnecessary to express” their viewpoint. They think “that remaining silent could protect their relationships and allow them to perform their job better”.14 Nonetheless, an overview of who these men were can perhaps serve as a starting point for further research into broadening the existing narratives of the surrender.

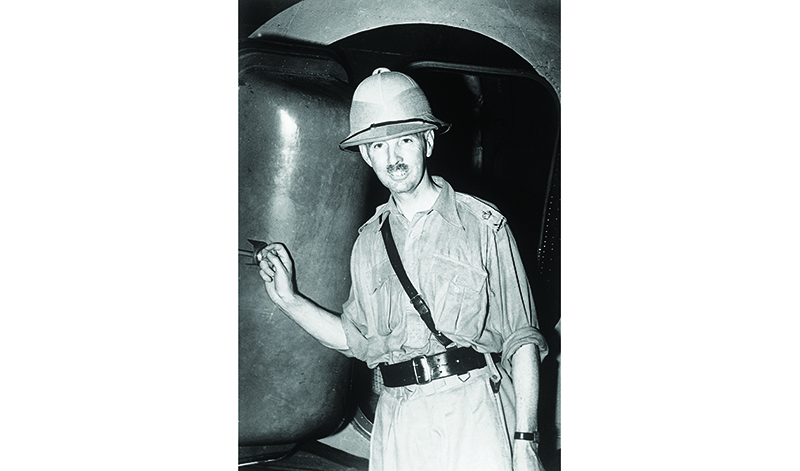

Cyril Hew Dalrymple Wild (1908–46)

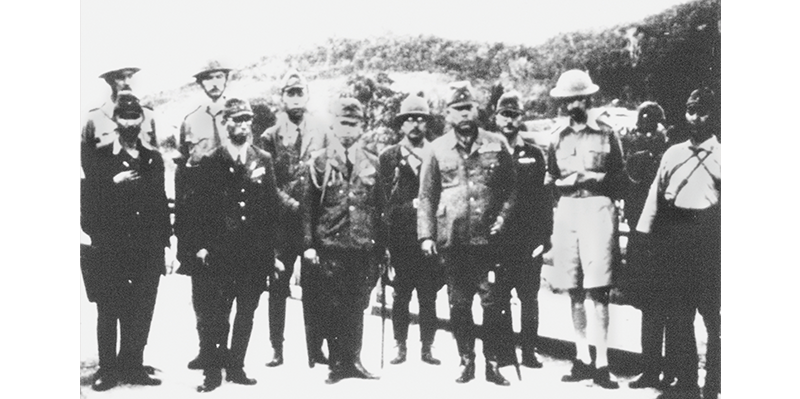

Among the eight, Wild is probably the most interesting. Wild, together with Percival, Newbigging and Torrance, had been members of the surrender party and were photographed walking towards the Ford Factory to meet with Lieutenant-General Tomoyuki Yamashita, commander of the Japanese 25th Army. It was Wild who carried the white flag.

Wild acted as Percival’s interpreter for the occasion. He was fluent in Japanese having studied the language while working for the Rising Sun Petroleum Company in Yokohama in 1931, leaving only in early 1941. Wild rejoined the British army in June 1940. As Heath’s General Staff Officer, he was given the task of speaking to journalists and was on duty at operations headquarters in Kuala Lumpur on 7 December 1941 when he heard the news of Japanese ships heading towards Malaya.15

Wild died in 1946 and conspiracy theories surround his death to this day, largely in part due to his postwar role as a War Crimes Liaison Officer for Malaya and Singapore, assisting the three War Crimes Investigation Teams operating in the region then.16

In September that year, Wild had testified before the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in Tokyo on the initial Japanese landings in Kota Bahru and subsequent atrocities by the Japanese army. Wild, however, died in a plane crash on 25 September 1946 in Hong Kong, en route to Singapore from Tokyo.17

In 2014, the Hong Kong broadsheet, South China Morning Post, revisited the incident in an article headlined “Cover Up at Kai Tak? ‘Allies Caused Hong Kong Plane Crash That Killed 19 to Assassinate British Investigator’”. The article cited war veteran Arthur Lane who said that at the time of the accident, Wild had been “building a solid case that could have seen the Japanese emperor held accountable for some of the worst atrocities carried out by his troops in the early decades of the last century”. It also made the sensational claim that Wild had been “killed to preserve the imperial lineage in Japan and halt the spread of communism across Asia”.18

Lane alleged that “a few days before his death, Colonel Wild had made it known to the American authorities that he had enough evidence to be able to convict Hirohito [the emperor of Japan] of war crimes, including bacteriological warfare experiments” and Wild “was then ordered to cancel any further work in this direction and to hand over all the documentation he had so far accumulated”.19

In her book about the people buried in Hong Kong Cemetery, teacher and historian Patricia Lim wrote that on “news of the crash there was jubilation amongst the Japanese in custody”. All interview transcripts and detailed notes relating to the War Crimes Tribunals were lost in the crash and all further trials compromised. Lim stated that while it is “impossible to find the cause of the crash”, “it was thought that the triads may have been involved in sabotaging the plane for a big payoff”.20

James Bradley, a former prisoner-of-war whose life Wild had saved while they were both working on the infamous Thai-Burma Railway, wrote a biography of his saviour titled Cyril Wild: The Tall Man Who Never Slept, first published in 1991. During his internment, Wild put his Japanese language skills to good use and relentlessly interceded on behalf of his fellow prisoners-of-war. This led his Japanese captors to call him nemuranu se no takai otoko (“the tall man who never slept”).21

Thomas Kennedy Newbigging (1891–1968)

Newbigging has generally been identified as the officer who carried the Union Jack as part of the surrender party that met the Japanese army at Ford Factory on 15 February 1942. This, however, is a matter of some dispute as one account suggests that it was Torrance who carried the Union Jack.22

Newbigging was the Deputy Adjutant-General, Malaya Command, from 1941 to 1942 and had received the Military Cross for his actions during World War I. He had first gone with Wild and Hugh Fraser, colonial secretary of the Straits Settlements, to deliver a letter from Percival to Yamashita following the morning meeting. They met with Colonel Ichiji Sugita (who would serve as Yamashita’s interpreter later that afternoon), who handed a letter to Newbigging requesting that Percival personally meet with Yamashita.23

A week after the surrender meeting, and while incarcerated at Changi Prison, Newbigging was said to have spoken to Sugita after British internees realised a massacre of the Chinese population was taking place. He is reported to have said: “I ask that you should not shoot any more Chinese and that you should not ask our men to assist you by burying them.”24

Newbigging was later interned in Formosa (present-day Taiwan) and then Manchuria. He retired in 1946.25

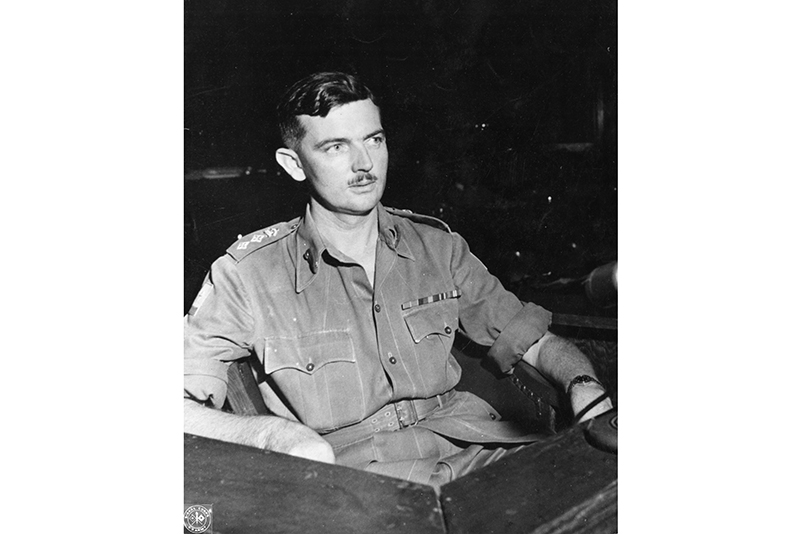

Kenneth Sanderson Torrance (1896–1958)

Born in Guelph in Ontario, Canada, Torrance had served with the Canadian Army in World War I where he was awarded the Military Cross. In the interwar years, he transferred to the British Army and served in India and then in Malaya at the outbreak of World War II. Torrance later served as Brigadier General Staff, Malaya Command, and was awarded the Order of the British Empire in the 1942 New Year’s Honours List ceremony for his bravery while serving the British forces during the Malayan campaign.26

After the fall of Singapore, Torrance was first interned in Changi Prison, then in Formosa and later in Mukden (present-day Shenyang), Manchuria. He returned to Guelph after the war, his health having been severely affected by his internment. Torrance died in his winter home in the Bahamas in 1958.27

Till today, Guelph remains proud of Torrance. In May 2023, online news site Guelph Today featured Torrance in an article titled “Guelph’s Military Contribution Goes Beyond Lt.-Col. John McCrae”.28

Alec Warren Greenlaw Wildey (1890–1981)

Wildey was Commander, HQ Anti-Aircraft Defences, Malaya, and the meeting at the Battle Box took place in his office. A recipient of the Military Cross for his actions in World War I, Wildey arrived in Singapore in 1937 as Commander, 3rd Anti-Aircraft Brigade Royal Artillery. From 1940 to 1942, he assumed the role of Commander, Anti-Aircraft Defences, Malaya.29

Unfortunately, soon after arriving in Singapore, Wildey was involved in a fatal car accident. On 23 December 1937, the press reported about a “fatal motor accident in Keppel Road soon after midnight on 20 Dec” in which Wildey was charged with “causing the death of a ricksha-puller by negligent driving”.30

Wildey was acquitted in February 1938, with the chief court inspector stating that he had received instructions from the deputy public prosecutor to ask for a withdrawal of the charge. A verdict of misadventure was returned with “no evidence of criminal negligence or rashness on the part of Col. Wildey”.31

In 1946, Wildey was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire. In the recommendation, it was said that during the Malayan Campaign, Wildey had “show[n] himself cool and resourceful in dealing with situations as they developed”.32

Ivan Simson (1890–1971)

Simson was Chief Engineer of the Malaya Command with the additional duties of Director-General of Civil Defence during the last six weeks of the Malayan Campaign.33 He was the officer who updated the meeting on 15 February 1942 of the dire water situation.

Before the outbreak of war, Simson had recommended an overhaul and construction of fixed defences but this was dismissed by the Malaya Command and Percival on the basis that such work was bad for morale.34

Simson’s views of the surrender can be found in his account of the Malayan campaign, Singapore: Too Little, Too Late: Some Aspects of the Malayan Disaster in 1942, first published in 1970.35

Arthur Harold Dickinson (1892–1978)

Dickinson was the only member of the civil government present at the meeting on 15 February 1942. He joined the Straits Settlements police force in Singapore in 1912, and most of his career in the Special Branch was spent in Singapore, Melaka and Penang.36

Dickinson was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire in 1937 for his “tactful handling” of a series of strikes in the Federated Malay States. In 1939, he was promoted to Inspector-General of Police, Straits Settlements, and established the Malayan Security Service in September that year. This replaced the Straits Settlements and Malayan Police Special Branches.37

In a blog entry in 2013, Dickinson’s great-granddaughter Johanna Whitaker recalled how throughout her childhood, she had heard stories of her great-grandparents during their period of internment in Changi Prison, eating “snails and cockroaches for sustenance throughout those tough years and when the war was over and they were released… they were mere skeletons”.38

Eric Whitlock Goodman (1893–1981)

Goodman was senior gunnery advisor to Percival and served as Commander Royal Artillery of the 9th Indian Division, Malaya. During the meeting on 15 February 1942, he had reported on the ammunition reserves. A recipient of the Military Cross in World War I, Goodman was also awarded the Distinguished Service Order in 1937.39

Goodman’s account of the meeting in his diary is factual in tone, stating that he attended a conference “in which it was decided that it was useless to continue the fight as water and ammunition were failing and food too was running short due to losses by capture. I think too that conditions in the native part of the city were a great anxiety – the numbers of unburied dead lying about”.40

Goodman died on 8 December 1981. In an obituary by Major Frederick James Howard Nelson, Goodman’s Brigade Major in the 9th Indian Division, Nelson remembered Goodman as one who whenever “things looked hopeless he was sure to appear in person and by his apparent unconcern for danger restored the confidence of all ranks”.41

Hubert Francis Lucas (1897–1990)

Lucas was Chief Administration Officer of the Malaya Command from 1940 to 1942. He fought in World War I and was educated at the Royal Military Academy as well as Cambridge University.42

In 1946, Lucas was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire. He was commended for having “tackled” the administrative problems of transportation, supply and accommodation during the Malayan Campaign with “coolness and resource”, and the good results achieved within the services were largely due to his leadership.43

In Retrospect

Ultimately, the decision to surrender was a unanimous one albeit, perhaps, with reluctance. In the spirit of counterfactual history (addressing the “what if” question), one cannot help but wonder what the outcome would have been if the decision to launch a counterattack to recapture Bukit Timah had been taken – a comment that Bennet had made, according to Wild, when the commanders were discussing the details of the surrender. However, Wild had dismissed the comment “made not as a serious contribution to the discussion but as something to quote afterwards”. Wild reported that the comment had been “received with silence”.44

On the 50th anniversary of the fall of Singapore in 1992, this writer, in an article for the Straits Times, posed the following question to four historians – two from the National University of Singapore, a historian from Japan and a historian from the United States: Could the British army have held on against the invading Japanese army in 1942 and turned the tide? All four were unanimous in saying that the Japanese would have eventually prevailed.”45

American military historian Stanley L. Falk said that there was no way the British could have held on and turned the tide: “Singapore was lost from the beginning. Given the preponderance of Japanese military strength and the fact that they could have brought in more military strength if needed, it was inevitable that Singapore would fall.”46

Singapore military historian Ong Chit Chung was of the opinion that the British could have held out for a while, but defeat was only a matter of time. “Even if a Rommel or a Montgomery or a Patton had been in a similar position, it would have been quite difficult for them to hold the island without air and sea power. They may have been able to delay the defeat but for how long I do not know,” said Ong.47

Japanese historian Shimizu Hajime observed: “The British may have outnumbered the Japanese by more than half, but the Japanese troops had greater fighting spirit, and this played a crucial role in their victory.”48

The scholarship for why Malaya fell so quickly is vast and complex, and continues to evolve as new documents are released from the archives and translations from Japanese sources are made available.49

The reasons for the British defeat have generally ranged from flaws in the overall British defence strategy for Singapore; the Allied commanders’ conduct during the battle; inadequate resources afforded to Percival; and generally ill-trained Allied troops to the bold and relentless “driving charge” strategy adopted by the Japanese army, and their ability to adapt as compared to the “set piece positional defensive battle” adopted by the British that “simply would not work in the terrain of northern and central Malaya”.50

Whatever decision taken on 15 February 1942 may not have made a difference to the final outcome. However, it is a decision that should not been viewed as the burden of just one man to bear. The room for dialogue and conversation on its narrative still remains open.

The meeting on 15 February 1942 when Lieutenant-General Arthur E. Percival, General Officer Commanding Malaya, made the decision to surrender with 11 other commanders took place at the Battlebox – an underground bunker at Fort Canning. Admission to the Battlebox is free. (For more details, see https://battlebox.sg/)

Entrance to the Battlebox, 2022. It is currently a museum and tourist attraction. Photo by Jimmy Yap.

Entrance to the Battlebox, 2022. It is currently a museum and tourist attraction. Photo by Jimmy Yap.

The actual surrender took place on the premises of the Ford Factory in Bukit Timah, which had been turned into the temporary headquarters of Lieutenant-General Tomoyuki Yamashita, Commander of the Japanese 25th Army. On the afternoon of 15 February, Percival met Yamashita at the factory to discuss surrender terms. Yamashita demanded an immediate, unconditional surrender and threatened to launch a devastating attack on the city that night. Percival signed the surrender document at 7.50 pm.

Facade of the old Ford Factory on Upper Bukit Timah Road. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Facade of the old Ford Factory on Upper Bukit Timah Road. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Today, the surrender site is known as the Former Ford Factory. It houses a permanent World War II exhibition by the National Archives of Singapore showcasing the events and memories surrounding the British surrender, the Japanese Occupation of Singapore and the legacies of the war. (For more information, visit https://corporate.nas.gov.sg/former-ford-factory/overview/).

Phan Ming Yen is an independent writer, researcher and producer. A former journalist and arts manager, his current areas of research are on the Malayan Campaign and Japanese Occupation in Singapore. He has written about 19th-century music in Singapore and also on the Syonan Symphony Orchestra during the Occupation.

Phan Ming Yen is an independent writer, researcher and producer. A former journalist and arts manager, his current areas of research are on the Malayan Campaign and Japanese Occupation in Singapore. He has written about 19th-century music in Singapore and also on the Syonan Symphony Orchestra during the Occupation.Notes

-

Clifford Kinvig, “General Percival and the Fall of Singapore,” in Sixty Years On: The Fall of Singapore Revisited, ed. Brian Farrell and Sandy Hunter (Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 2002), 240. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 940.5425 SIX-[WAR]) ↩

-

Stephanie Ho, “Battle of Singapore,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 19 July 2013. ↩

-

Stanley Tan Tik Loong, Reflections & Memories of War Vol 1: Battle of Singapore: Fall of the Impregnable Fortress (Singapore: National Archives of Singapore, 2011), 287. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 940.5425957 TAN) ↩

-

“Lieutenant General Arthur Percival’s Dispatch on Operations, 8 December 1941 to 15 February 1942,” in Disaster in the Far East 1940–1942: The Defence of Malaya, Japanese Capture of Hong Kong and the Fall of Singapore, comp. John Grehan and Martin Mace (Barnsley, Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military, 2015), 310. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 940.5425 DIS-[WAR]) ↩

-

“Prince of Wales and H.M.S. Repulse Sunk off Malaya,” Malaya Tribune, 11 December 1941, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Henry Gordon Bennett, Why Singapore Fell (London: Angus and Robertson Ltd, 1944). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 940.5425 BEN) ↩

-

“Lieutenant General Henry Gordon Bennett,” Australian War Memorial, accessed 8 March 2024, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/P11032385. ↩

-

Arthur Ernest Percival, The War in Malaya (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1949), 33. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 940.53595 PER) ↩

-

“ Malayan General Dies, 68,” Straits Times, 14 January 1954, 8. (From NewspapersSG) ↩

-

“Minutes of Meeting by Arthur Earnest Percival As Copied from the Original by Tan Teng Teng, Founder Curator of the Battlebox,” in Private Papers of Lieutenant General A E Percival, Imperial War Museums, https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/1030003865, and also from Romen Bose, Secrets of the Battlebox (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish, 2011), 112. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 940.5425 BOS-[WAR]) ↩

-

Bose, Secrets of the Battlebox, 112. ↩

-

James Bradley, Cyril Wild: The Tall Man Who Never Slept (Nemuranu Se No Takai Otoko) (West Sussex: Woodfield, 1997), 40. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. R 940.547252092 BRA-[WAR]) ↩

-

Cyril Hew Dalrymple Wild was promoted to full Colonel in 1946. See Bradley, Cyril Wild, 122. ↩

-

Mehtap Sarikaya and Sabahat Bayrak Kök, “Could Participative Decision Making Be Solution for Oganizational Silence Problem,” European Scientific Journal (August 2016 Special Edition): 15, https://eujournal.org/index.php/esj/issue/view/243. ↩

-

Justin Corfield and Robin Corfield, The Fall of Singapore: 90 Days: November 1941– February 1942 (Singapore: Talisman, 2012), 668. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 940.5425957 COR-[WAR]) ↩

-

Bradley, Cyril Wild, 122. ↩

-

Imperial War Museum, “Colonel Cyril Hew Dalrymple Wild, the Third Son of Herbert Wild, Bishop of Newcastle,” 1942–46, Private Records. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. IWM 66/227/1) ↩

-

Julian Ryall, “Cover Up at Kai Tak? Allies ‘Caused Hong Kong Plane Crash That Killed 19 To Assassinate British Investigator’,” South China Morning Post, 9 August 2014, https://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/article/1569054/blame-resistant. ↩

-

Ryall, “Cover Up at Kai Tak?” ↩

-

Patricia Lim, Forgotten Souls: A Social History of the Hong Kong Cemetery (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2011), 539, https://hkupress.hku.hk/index.php?route=product/product&product_id=923. ↩

-

Bradley, Cyril Wild, 5–6. ↩

-

A discussion on who carried the Union Jack can be found in Reflections & Memories of War Vol 1: Battle for Singapore: Fall of the Impregnable Fortress (p. 293), and Cyril Wild (p. 91). In Cyril Wild’s biography, James Bradley states that Thomas Kennedy Newbigging carried the Union Jack when contact was first made, while Kenneth Sanderson Torrance carried the Union Jack at the surrender meeting with Yamashita. In The Fall of Singapore: 90 Days (p. 668), a photograph of the surrender party identifies Newbigging as the officer who carried the Union Jack. ↩

-

Peter Thompson, The Battle of Singapore: The True Story of the Greatest Catastrophe of World War II (London: Piatkus, 2006), 487. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. 940.5425) ↩

-

Thompson, The Battle of Singapore, 536. ↩

-

Corfield and Corfield, The Fall of Singapore, 668. ↩

-

Corfield and Corfield, The Fall of Singapore, 667. ↩

-

Ed Butts, “Guelph’s Military Contribution Goes Beyond Lt.-Col. John McCrae,” Guelph Today, 20 May 2023, https://www.guelphtoday.com/then-and-now/guelphs-military-contributions-go-beyond-lt-col-john-mccrae-7007689. As of 2012, some historians have commented on the uncertainty of his date of death, noting that several sources stated it as 1948 although in 1957 Torrance was recorded as having travelled from the Bahamas to Liverpool on the Empress of Britain. See Corfield and Corfield, The Fall of Singapore, 667. ↩

-

Butts, “Guelph’s Military Contribution Goes Beyond Lt.-Col. John McCrae.” John McCrae was a poet and solider who wrote the famous World War I poem, “In Flanders Fields”. ↩

-

“British Army Officers 1939–1945,” World War II Unit Histories & Officers, accessed 11 March 2024, https://www.unithistories.com/officers/Army_officers_W01a.html. ↩

-

“Colonel Charged with Causing Death: Sequel to Keppel Road Accident,” Straits Budget, 23 December 1937, 8. (From NewspapersSG) ↩

-

“Colonel Wildey Acquitted,” Malaya Tribune, 18 February 1938, 8; “Counsel Blames Bad Keppel Road Lighting,” Straits Budget, 3 March 1938, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Recommendation for Award for Wildey, Alec Warren Greenlaw, Rank: Colonel,” WO 373/87/225, The National Archives, accessed 8 March 2024, https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/D7391397. ↩

-

“Simson, Ivan,” Generals.dk, accessed 11 March 2024, https://generals.dk/general/Simson/Ivan/Great_Britain.html. ↩

-

Malcolm H. Murfett, Between Two Oceans: A Military History of Singapore from First Settlement to Final British Withdrawal (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 186. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 355.0095957 BET) ↩

-

Ivan Simson, Singapore: Too Little, Too Late: Some Aspects of the Malayan Disaster in 1942 (London: Leo Cooper, 1970). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 940.5425 SIM-[WAR]) ↩

-

Leon Comber, Malaya’s Secret Police: The Role of the Special Branch in the Malayan Emergency (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2008), 47. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 363.283095951 COM) ↩

-

“New Inspector-General, Police Appointed,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 5 August 1939, 7. (From NewspaperSG); Comber, Malaya’s Secret Police, 26. ↩

-

Johanna Whitaker, “Singapore – Where East Meets West,” Visions of Johanna, 28 November 2013, https://visionsofjohanna.org/singapore-where-east-meets-west/. ↩

-

“Brigadier E.W. Goodman,” Britain at War, accessed 8 March 2024, https://www.britain-at-war.org.uk/WW2/Brigadier_EW_Goodman/. ↩

-

“Brigadier E.W. Goodman: Singapore,” Britain at War, accessed 8 March 2024, https://www.britain-at-war.org.uk/WW2/Brigadier_EW_Goodman/html/singapore.htm. ↩

-

“Brigadier E.W. Goodman: Obituary,” Britain at War, accessed 8 March 2024, https://www.britain-at-war.org.uk/WW2/Brigadier_EW_Goodman/html/orbituary.htm. ↩

-

“Brigadier Hubert Francis Lucas,” The Peerage, accessed 11 March 2024, https://www.thepeerage.com/p35016.htm. ↩

-

“Recommendation for Award for Lucas, Hubert Francis, Rank: Temporary Brigadier,” WO 373/87/222, The National Archives, accessed 8 March 2024, https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/D7391394. ↩

-

Bradley, Cyril Wild, 40. ↩

-

Phan Ming Yen, “British Could Not Have Held On,” Straits Times, 15 February 1992, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Phan, “British Could Not Have Held On.” ↩

-

Phan, “British Could Not Have Held On.” ↩

-

Phan, “British Could Not Have Held On.” ↩

-

See Brian P. Farrell, “The Other Side of the Hill: Western Interpretations of the Japanese Experience in the Malayan Campaign and Conquest of Singapore 1941–42,” NIDS Military History Studies Annual, no. 19 (March 2016): 80–96, https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/11442214/1/1. ↩

-

Farrell, “The Other Side of the Hill,” 92. ↩