The Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan Collection: A Treasure Trove of Information

Materials donated by the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan offer unique perspectives into the history of the Hokkien community here and the association’s contributions to the nation’s social and cultural landscape.

By Ang Seow Leng and Seow Peck Ngiam

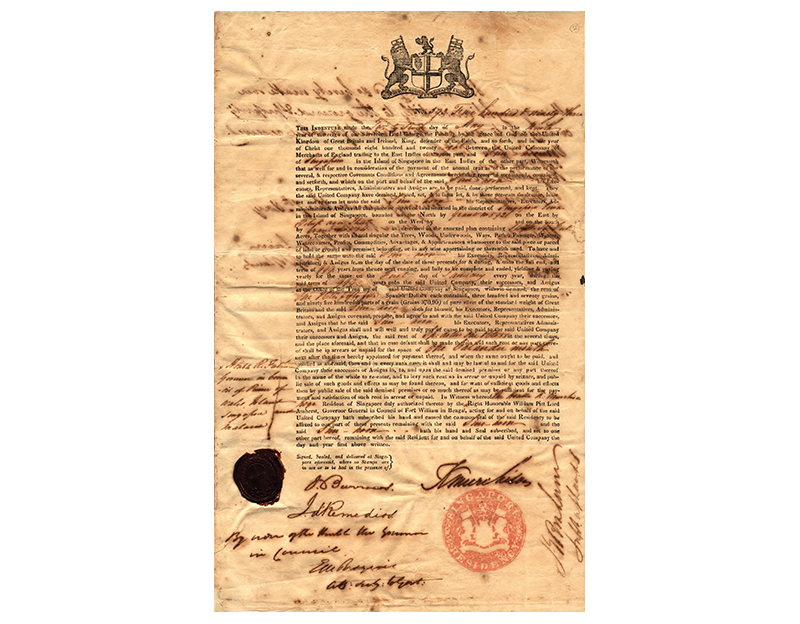

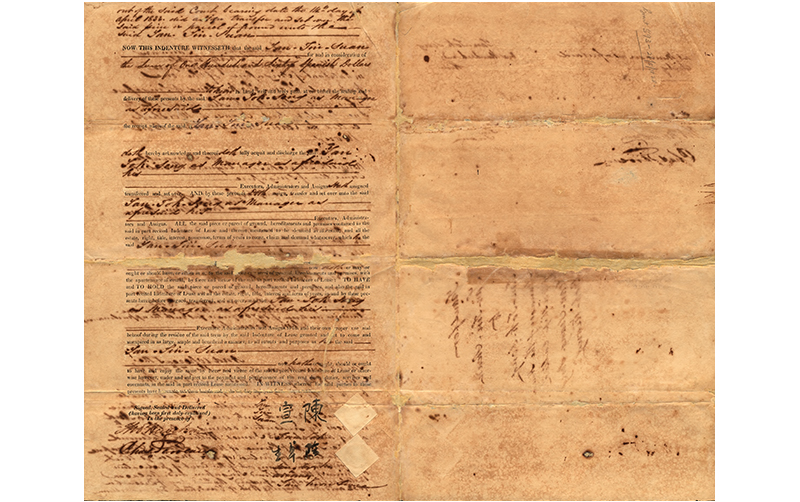

A title deed dating back to 1838 with pioneer businessman Tan Tock Seng’s signature. Records of schools like Tao Nan, Ai Tong and Nan Chiau. Documents regarding the relocation of temples and cemeteries. These are just some of the more than 4,300 documents that the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan donated to the National Library in 2021.

Other documents include land records, rental records, receipts dating back to the Second World War, old business correspondences, photographs and minutes of meetings. All these materials are now part of the National Library’s Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan Collection.

This collection is important because these papers shed light on many important institutions in Singapore, especially those relating to the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan. Among the documents donated, for example, are nine early title deeds for the land that the Thian Hock Keng temple sits on.1 Located on Telok Ayer Street, Thian Hock Keng is one of Singapore’s oldest Hokkien temples and also a national monument.

From these documents, which were kept in a safe for many decades, we learn that Tan Tock Seng had acquired multiple plots of land in Telok Ayer between 1838 and 1839 at prices ranging from 160 to 200 Spanish silver dollars per plot for the construction of the temple.2 He purchased these land parcels from the resellers who had originally bought them from the British East India Company.3

The purchase of land in Singapore during the early 19th century was usually in the form of a 999- or 99-year lease issued by the Straits Settlements government, where the lease or grant was subject to a yearly quit rent.4

A document numbered 593 and dated 1828 shows that a Sim Loo-ah had purchased a plot of land on Telok Ayer Street and paid a quit rent of 1.55 Spanish silver dollars per year. This 1828 land title deed is believed to be the oldest land title deed found in Singapore.

A quick survey of land title deeds reveals how quickly the price of land in Telok Ayer appreciated in those early years. Just four years later, in 1832, Sim sold the land to a Tan Leng for 100 Spanish silver dollars. Tan Leng in turn sold the same plot to Tan Tock Seng in 1838 for 170 Spanish dollars, and the title deed bears the latter’s signature.

The construction cost of the temple was about 37,000 Spanish dollars. This was borne by wealthy Hokkiens in Singapore and ship-owners from Zhangzhou and Quanzhou in China. Topping the list of donors was Tan Tock Seng, who gave $3,074. He was followed by another local businessman, See Hoot Kee, who contributed $2,400.5

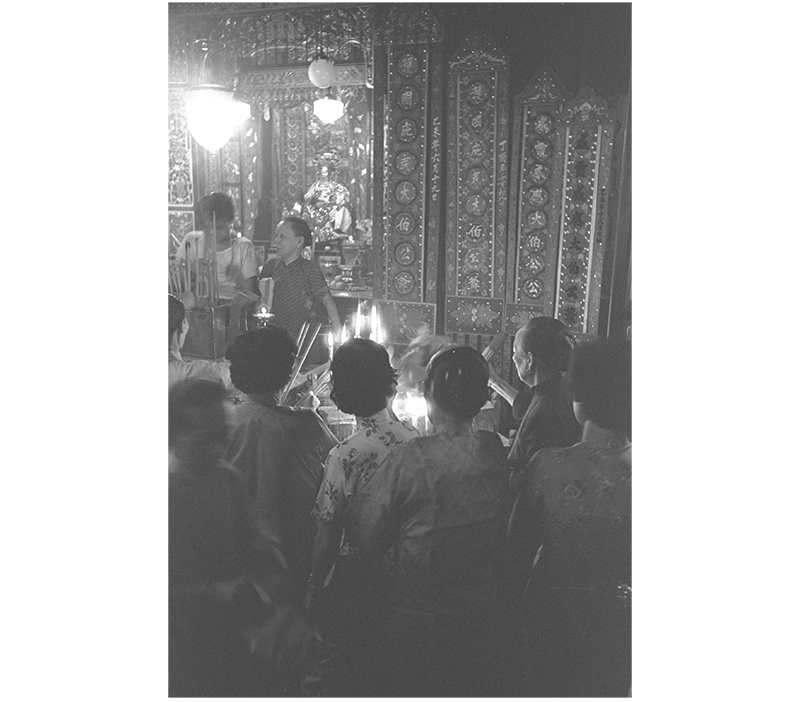

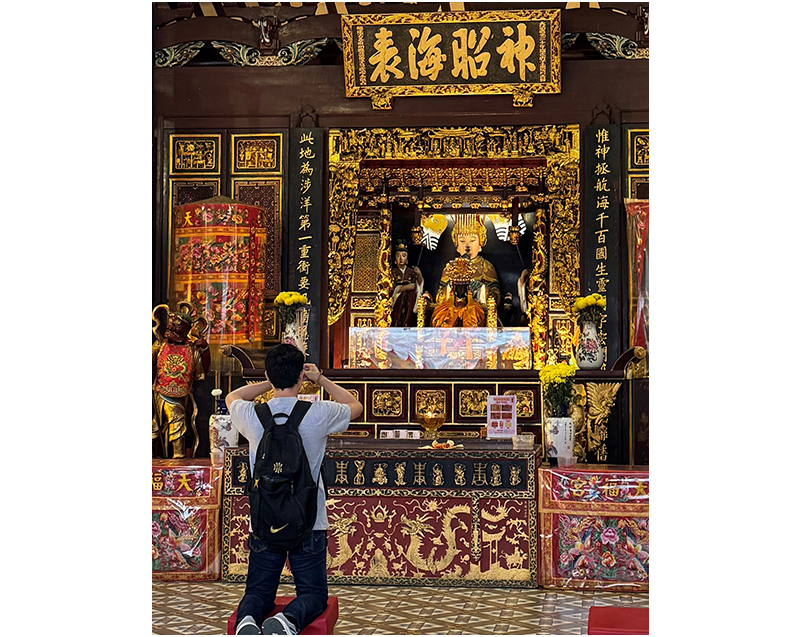

Thian Hock Keng – More Than Just a Religious Space

Construction of the present Thian Hock Keng temple at 158 Telok Ayer Street began in 1839 and was completed by 1842.6 However, the temple actually traces its roots to a simple prayer house that had been set up in 1821 along the shoreline of Telok Ayer Basin. It was dedicated to the Goddess of the Sea, Mazu (妈祖), who is the protector of sailors, fishermen and travellers. Chinese immigrants would go to the prayer house to give thanks for their safe passage to Singapore.

On 28 June 1973, Thian Hock Keng was gazetted as a national monument. The architecture of the temple is consistent with Chinese temple architectural traditions from Minnan (a southern Fujian province in China), such as complex timber posts and beam structures with decorative features like the “swallow tail” roof ridge and intricate carvings.7 The temple was repaired and restored to its current state in the mid-1990s and won an honourable mention in the 2001 UNESCO Asia-Pacific Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation.8

Formation of the Hokkien Huay Kuan

In addition to shedding light on the early history of the temple, the archival materials are also a window into the Hokkien community in Singapore. This is because besides being a place of worship, Thian Hock Keng was also a social centre where Hokkien leaders would gather to make important decisions regarding the Hokkien community, business issues, fund-raising plans, management of burial lands and even registering marriages.9

Between 1840 and 1915, a small group of merchants and rich Hokkien businessmen such as Khoo Cheng Tiong and Tan Boo Liat helped hold the council elections of Thian Hock Keng Temple. In 1915, the council prepared a constitution to register with the colonial government but was exempted from registration in 1916. The council was renamed Thian Hock Keng Hokkien Huay Kuan (huay kuan means “clan association”).10 This marked a new phase of the Huay Kuan as it gained prominence in the Hokkien community. Management of Thian Hock Keng Temple came under the purview of the Huay Kuan, changing the dynamics from when it first started as a social arm of the temple.

In 1937, the Hokkien Huay Kuan was registered as a non-profit organisation under the Companies Ordinance, with a focus on education.11 Its affiliated schools include Tao Nan School, Ai Tong School, Chong Hock Girls’ School (today’s Chongfu School), Nan Chiau Primary School, Nan Chiau High School and Kong Hwa School.12 The Huay Kuan also led the way in establishing Nanyang University (present-day Nanyang Technological University), raising funds and donating 523 acres of land for the university’s campus in Jurong.13

Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan Collection

While Thian Hock Keng’s historical land title deeds are part of the 2021 donation by the Hokkien Huay Kuan to the National Library, the majority of the collection are postwar materials. They can broadly be classified into the following categories: clan operations and activities, school operations, management of temples and burial grounds, and management of properties.

Eight sets of minutes14 provide a detailed look into the Management Council of the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan’s decisions from 1950 to 1984, while five other sets of minutes from various departments15 of the Huay Kuan offer insights into their specific activities between 1962 and 1987. There is also a dedicated set of minutes that presents meticulously documented motions for discussion and important documents,16 as well as records pertaining to amendments of the Huay Kuan’s articles, notices and circulars.17

Also included are official correspondences from 1950 to 1977, which offer glimpses into the clan’s external interactions with entities such as the Housing and Development Board Branch, and Public Works Department Roads Branch.18

Records relating to the schools managed by the Huay Kuan help to illuminate the history of Chinese education in Singapore. Documents such as balance sheets and donation records provide perspectives on the changing educational landscape such as school relocation in the late 1960s.

Highlights include documents on an exchange of land between Nan Chiau Girls’ High School (comprising both primary and secondary levels) and Chung Cheng High School (Branch), which were both formerly located at Kim Yam Road, and the rebuilding of Nan Chiau’s new campus at the same site. To meet Nan Chiau’s growing student population and to facilitate its reconstruction efforts, the campus of its secondary school was temporarily relocated to Guillemard Road. Its primary school campus continued to function at Kim Yam Road from 1965 to 1968. Nan Chiau at Kim Yam Road was rebuilt and expanded in 1969, and brought both the primary and secondary campuses under one roof.19 Chung Cheng High School (Branch), on the other hand, shifted to Guillemard Road in 1969.20

The materials in the collection also reveal historical insights into the Huay Kuan’s role as the guardian of sacred spaces. For instance, documents from 1949 to 1982 detail the relocation of Kim Lan Beo. Established in 1830, Kim Lan Beo is one of Singapore’s oldest temples and counts prominent Hokkien individuals like Lim Boon Keng and See Tiong Wah in its past management committees.21 It was originally at Yan Kit Road in Tanjong Pagar and came under the management of the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan in 1960. The documents track the journey of the temple’s eventual relocation to Kim Tian Road in Tiong Bahru, culminating in its reopening in 1984.

Beyond temple stewardship, the collection showcases the Huay Kuan’s management of burial grounds like Kopi Sua (羔丕山) near Mount Pleasant Road22 (1961–73) and Leng Kee Sua (1951–80, 麟记山) in Tiong Bahru. Documents reveal the complexities of maintaining these spaces, such as surveying squatter settlements and addressing illegal construction (at Leng Kee Sua) and dealing with land acquisition by the government due to urban planning.

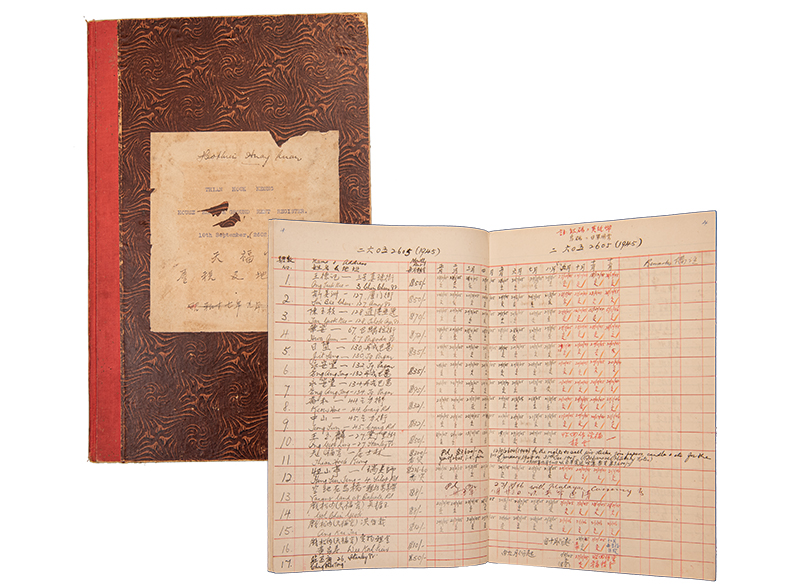

The collection also holds materials that document property rentals under Thian Hock Keng dating back to 1942. For example, a detailed rental register sheds light on the shops – such as Eng Aun Tong (永安堂) owned by businessman Eu Tong Sen – that leased the temple’s properties from 1942 to 1948.23

Beyond these property registers and account records are a wealth of papers pertaining to land and rental agreements for various properties and villages, including Mandai Tekong Village (万利泽光), off Mandai Road.24

The photographs in the collection also provide information about the Huay Kuan and its activities. These showcase past management committees and capture unique moments such as traditional mass weddings, school life, burial grounds – bringing the clan’s past vividly to life.

This brief survey only touches the surface of what is available in the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan Collection. You can request to view the materials highlighted in this article (access information can be found in the Notes listed below), or find out more by consulting us (via email at ref@nlb.gov.sg) or at the reference counter on Level 11 of the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library, National Library Building).

Ang Seow Leng is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include managing the Singapore and Southeast Asian Collection, developing content as well as providing reference and research services relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia.

Ang Seow Leng is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include managing the Singapore and Southeast Asian Collection, developing content as well as providing reference and research services relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia. Seow Peck Ngiam is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include selection, evaluation and management of materials for the Chinese and donor collections. She also conducts research and writes on collection highlights for the library.

Seow Peck Ngiam is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include selection, evaluation and management of materials for the Chinese and donor collections. She also conducts research and writes on collection highlights for the library.Notes

-

The digitised title deeds are available at NL Online: “新加坡福建会馆: 天福宫早期地契”; Thian Hock Keng Temple: Land Title Deeds, 1828–1838. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RRARE 346.59570438 THI) ↩

-

Xie Yanyan 谢燕燕, “Tianfu gong di qi yanjiu” 天福宫地契研究 [Research on the land title of Tin Hock Palace],” in Nanhai mingzhu tianfu gong 南海明珠天福宫 [South China Sea Pearl Thian Hock Temple] (新加坡: 新加坡福建会馆, 2010), 310–13. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Chinese RSING 203.5095957 NHM) ↩

-

Tong Yong Chuan, “Rare China Artefacts To Go on Display Here,” Straits Times, 14 November 2012, 2–3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Straits Settlements, Colonial Secretary’s Office, Annual Report on the Social and Economic Progress of the People of the Straits Settlements, 1937 (Singapore: Straits Settlements. Colonial Secretary’s Office, 1937), 84. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.51 SSCSOA) ↩

-

Guardian of the South Seas: Thian Hock Keng and Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan (Singapore: Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan, 2006), 28. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 369.25957 GUA) ↩

-

“Thian Hock Keng (Temple of Heavenly Fortune),” in Chinese Epigraphy in Singapore 1819–1911, ed. Kenneth Dean and Hue Guan Thye (Singapore: NUS Press; Guilin City: Guangxi Normal University, 2017), 124. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 495.111 DEA) ↩

-

“No. 158 Telok Ayer Street,” Urban Redevelopment Authority, accessed 15 January 2024, https://www.ura.gov.sg/-/media/Corporate/Get-Involved/Conserve-Built-Heritage/AHA/2001/AHA-2001—158-Telok-Ayer-Street.pdf. ↩

-

“Project Profiles for 2001 UNESCO Heritage Award Winners,” UNESCO, accessed 15 January 2024, https://articles.unesco.org/sites/default/files/medias/fichiers/2023/06/2001-winners.pdf. ↩

-

Guardian of the South Seas, 144. ↩

-

“About Us,” Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan, accessed 15 January 2024, https://www.shhkca.com.sg/about. ↩

-

Guardian of the South Seas, 89–91. ↩

-

Xinjiapo fujian huiguan zhi jian weiyuanhui huiyi lu, 1950–1984 新加坡福建会馆执监委员会会议录, 1950–1984 [Minutes of the executive committee of the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan, 1950–1984] (Singapore: n.p., 1946–1965). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS 369.25957 XJP [HHK]) ↩

-

Xinjiapo fujian huiguan zhi jian weiyuanhui huiyi lu, 1962–1987 新加坡福建会馆执监委员会会议录, 1962–1987 [Minutes of the executive committee of the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan, 1962–1987] (Singapore: n.p., 1946–1965). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS 369.25957 XJP [HHK]) ↩

-

Yi’an ji zhongyao wenjian, 1948–1971 议案及重要文件, 1948–1971 [Proposals and important documents, 1948–1971] (Singapore: n.p., 1946–1965). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS 369.25957 XJP [HHK]) ↩

-

Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan Collection: Amendments to the Association’s Articles, Notices and Circulars (Singapore: n.p., 1981). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 369.25957 SIN [HHK]) ↩

-

[Xinjiapo fujian huìguan zhencang] : [Xìnjian], 1950–1952 [新加坡福建会馆珍藏]: [信件], 1950–1952 [Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan Collection]: [Letters], 1950–1952 (Singapore: n.p., 1946–1965). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS 369.25957 XJP [HHK]); [Xinjiapo fujian huiguan zhencang]: [Putong zhongwen laiwang wenjian], 1964–1977 [新加坡福建会馆珍藏]: [普通中文来往文件], 1964–1977 [Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan Collection]: [General Chinese correspondence documents], 1964–1977] (Singapore: n.p., 1964–1977). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS 369.25957 XJP [HHK]) ↩

-

Nan qiao nu zhong qingzhu chuang xiao nian sān zhounian ji xin xiaoshe luocheng jinian tekan 南桥女中庆祝创校廿三周年暨新校舍落成纪念特刊 [Nanqiao Girls’ High School celebrates the 23rd anniversary of the founding of the school and the completion of the new school building special issue] (新加坡: 南桥女子中学校, 1970), 10. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 373.5957 NQN) ↩

-

“School History,” Chung Cheng High School (Yishun), accessed 6 February 2024, https://www.chungchenghighyishun.moe.edu.sg/our-cchy/school-history/. ↩

-

“Chuantong wenhua liulan – jinlan miao” 传统文化浏览—金兰庙 [Cultural walkabout – Kim Lan Beo Temple], Chuan Deng 传灯, no. 59 (January 2014), 7, shhk.com.sg/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/SHHK-Newsletter-59.pdf. ↩

-

British Royal Air Force, “Part of a Series of Aerial Photographs Showing Central Singapore,” 17 February 1946, photograph. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 158270) ↩

-

[Xinjiapo fujian huiguan zhencang] : Tianfu gong erzhan qijian chanye dengji ji xiangguan wénjian, 1942–1948 [新加坡福建会馆珍藏]: 天福宫二战期间产业登记及相关文件, 1942–1948 [Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan Collection]: Thian Hock Keng Industrial Registration and Related Documents During World War II, 1942–1948 ([新加坡], 1942–1948). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS 369.25957 XJP-[HHK]) ↩

-

Ratnala Thulaja Naidu, “Chinese Villages in the North,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 2005. ↩