W. Somerset Maugham: Secrets from the Outstations

W. Somerset Maugham’s visits to Singapore in the 1920s inspired some of his greatest fictional works, but these stories also triggered a fierce backlash against him throughout British Malaya.

By T.A. Morton

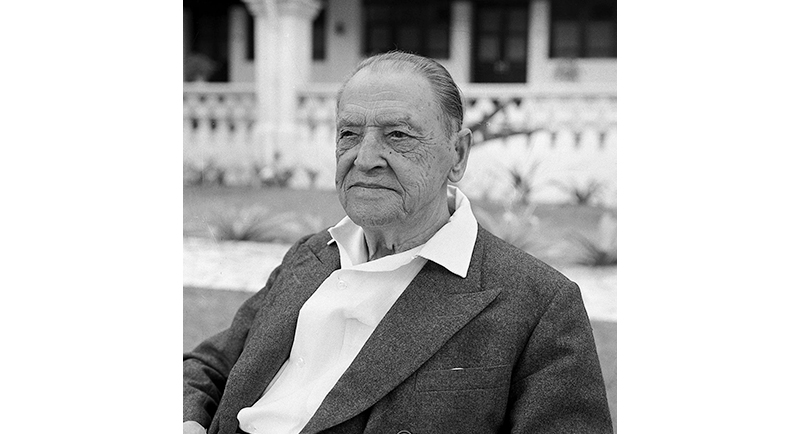

In April 1921, William Somerset Maugham – the bestselling novelist, famed playwright and master of short stories – landed in Singapore. Then aged 47, Maugham was already considered one of the world’s most well-known writers. During his lifetime, he penned 20 novels, filled nine volumes of short stories, wrote 31 plays and published several volumes of non-fiction.

However, it was his arrival in Singapore that marked a turning point in Maugham’s career. Encountering locals, empire builders, missionaries and the earliest cosmopolitan travellers, Maugham discovered a treasure trove of “new types” that appealed to his imagination.1 Yet, as a former doctor and an avid note-taker, he quite literally took these individuals at their word. This approach led to some of his most celebrated short stories, but it also damaged his reputation due to the insensitivity of publicly airing secrets for his own benefit.

Upon his arrival, the Malaya Tribune reported that “Mr W. Somerset Maugham, famous British playwright, some of whose productions are well-known here, is at present staying at the Van Wijk Hotel. He is seeking some Eastern Colour for some of his future work”.2

Maugham was accompanied by his private secretary, Gerald Haxton, during his trips. Haxton was adventurous and easy-going and was an asset to the shy writer. Maugham had a speech impediment, a stammer that tormented him over periods of his life, and he was unable to fall easily into conversation. It left him feeling self-conscious and often humiliated. It was Haxton who would pass hours talking to people they encountered on ships, in hotels and in clubhouse bars, and then relay their stories back to Maugham.

The expatriate society of British Malaya was thrilled by the arrival of such a popular writer, and Maugham was quickly inundated with invitations to parties and dinners. Their only mistake, perhaps, was that, during their cocktail hours, drinking sundowners before their lavish dinner parties, they revealed too much of themselves.

Singapore was then, like now, one of the great ports of the East. It was the bustling heart of Southeast Asia and a jewel of the British Empire. When Maugham docked, it was going through a period of prosperity with the boom of the rubber trade due to the expansion of the motor trade in the United States.

After the First World War, tin and rubber prices soared and fortunes were to be made in Southeast Asia. An influx of British expatriates, who referred to themselves as “Empire builders”, consisted of people migrating for work, either as government officials to uphold British rule or people moving away for monetary gain. Maugham found these “new” types intriguing, and often in some bar or club, Maugham and Haxton would hear extraordinary tales from people who were living seemingly ordinary lives. Maugham wrote: “[I]n those parts of the world where civilisation is worn thinner. I found the unique man far easier to see.”3 This could be due to the lack of social constraints and ties from home, the new climate; people were living differently and had stories to tell.

Inspiration for Stories

Maugham and his partner Haxton journeyed throughout Southeast Asia during the 1920s. In 1921, he spent six months in the region and another four months in 1925. Maugham and Haxton travelled extensively through British Malaya, the Dutch East Indies, French Indochina and Siam. Being a celebrity, his movement in these parts of the world did not go unnoticed. As the Singapore Free Press noted in May 1921: “Mr W. Somerset Maugham has been taking the opportunity during his visit to Kuala Lumpur to acquaint himself with the routine of a planter’s life.”4

Maugham was greatly inspired by the life of a plantation manager. Most of his Far Eastern tales, short stories based in Malaya, take place in and around plantations, and when looking at old articles of that time, it is evident what inspired him. The deaths of plantation managers were avidly reported by the local papers.

In November 1916, the Malaya Tribune reported that “Mr Gilbert Goundry was found dead on Monday morning with a deep wound in the temple, and with one hand clutching the trigger of a double-barrelled shot gun”.5 Just over a week later, the Straits Times reported that the manager of the rubber estate in Johor had been killed. “Mr Wilson was shot dead at nine this morning… the assailant escaped and got into the jungle and so far has not been captured.”6

These stories provided Maugham with material and the “Eastern colour” he was in search of. Maugham wrote that “[o]ften in some lonely post in the jungle or in a stiff, grand house, solitary in the midst of a teeming Chinese city, a man has told me stories about himself that I was sure he had never told to a living soul. I was a stray acquaintance whom he had never seen before and would never see again, a wanderer for a moment through his monotonous life, and some starved impulse led him to lay bare his soul”.7

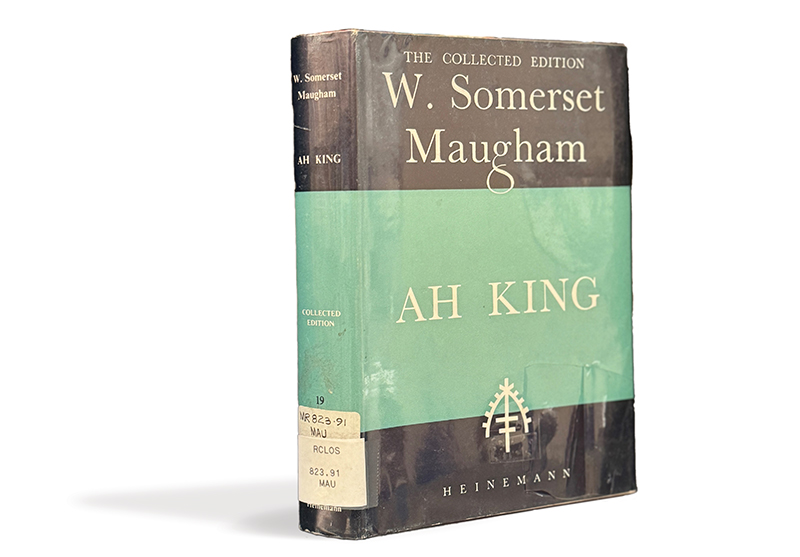

It was during these occasions that Maugham first heard about the incestuous affair of the brother and sister he wrote about in “The Book Bag”, a short story in the anthology Ah King.8 A trader staying in the same residence as Maugham and Haxton had apparently told them the story of an English wife’s discovery of her husband’s “half-caste” children, which Maugham wrote about in “The Force of Circumstance”.9

One evening in Sumatra, Maugham and Haxton had agreed to dine but Haxton was running late. Maugham waited and was then forced to eat alone. He was furious after dinner; it was then that Haxton, drunk, rushed in apologising and saying, “But I’ve got a corking good story for you!”10 He went on to relay the story that became “Footprints in the Jungle”, about the death of Mrs Cartwright’s first husband, Reggie Bronson, shot dead by her lover after she became pregnant with the lover’s child. Owing to the lack of evidence to convict, the body had to be removed quickly from the jungle due to the heat.11

Murder was a common theme in Maugham’s Far Eastern stories. He referred to a “murderous heat”, which caused his characters to become mad and commit murder.

Maugham engaged his readers by creating very entertaining stories based on what he came across here, and even though the murderers sometimes confess their sins, they live on freely keeping that stiff upper lip. Their social manners and customs are embedded within their club life; they meet to play bridge and dress for dinner despite the heat. His characters came out to the East on the promises of a better life for the future. However, once here, they are forced to battle against the terrain, customs and themselves. Their mask quickly slips, revealing deeply flawed people. Klaus W. Jonas writes that Maugham’s society in the East represents some sort of “micro-England” in that those who live here try to maintain their customs despite the environment they now dwell in.12

Maugham’s Englishwomen in the East exclude themselves from all foreign influences. In the short story, “Door of Opportunity,” he wrote, “they make a circle that was more provincial than any in the smallest town in England”.13

During his time here, Maugham was interviewed by the Malay Mail. The journalist wrote: “The interview ended with some appreciative remarks from Mr. Maugham on the beauty of Malaya, where, he complained, people ‘grumbled at the hardships of exile’ when they had more of the ‘conveniences of civilisation’ than in England.”14 This astute remark from Maugham about the expatriates heralded a warning of what Maugham was going to write about the people he encountered here.

The Letter/The Proudlock Case

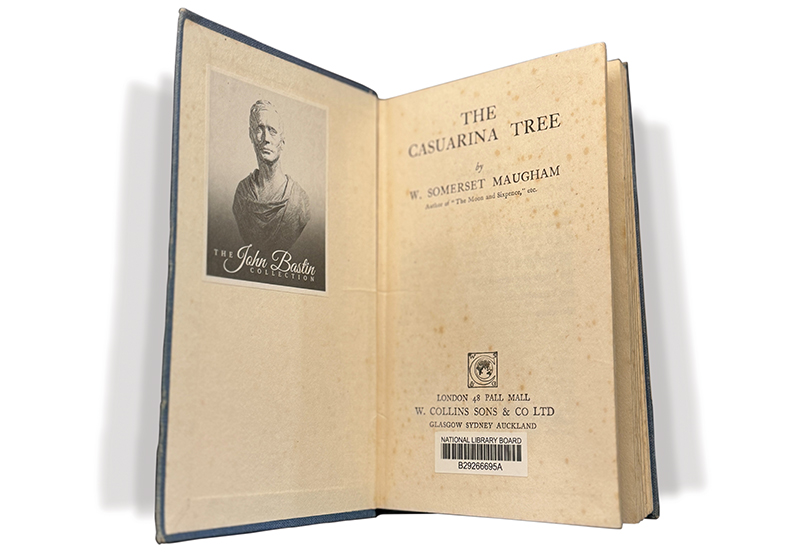

Maugham’s travels through Southeast Asia resulted in his short story collection, The Casuarina Tree, published in 1926. The collection consists of six stories, all of which feature characters based in the region. One story in particular riled up the expatriate community – “The Letter”.15 This is probably one of Maugham’s most famous stories and is based on a true event: the arrest and conviction of Ethel Proudlock in 1911, in Kuala Lumpur, for killing a man.

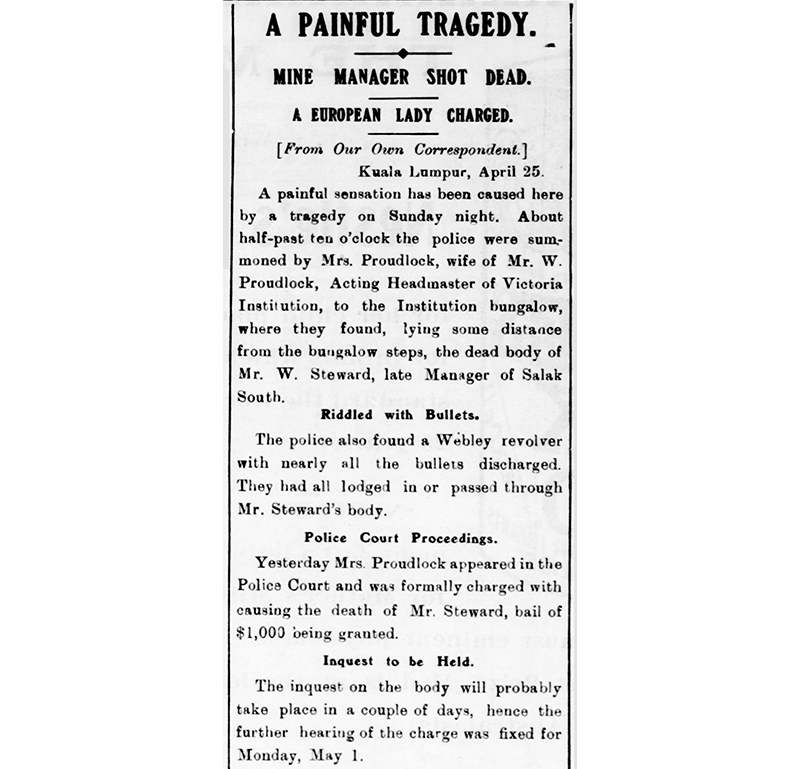

On 23 April 1911, William Steward, the former manager of the Salak South Tin mines, was dining at the Empire Hotel with friends when he abruptly got up and announced that he had an appointment at 9 pm that evening. Steward went to call on the Proudlocks, friends of his, and found Mrs Ethel Proudlock home alone. Her husband, William Proudlock, acting headmaster of the Victoria Institution House, was out dining with a friend. Steward arrived by rickshaw and told the driver to wait for him outside. Mrs Proudlock welcomed him into the house.

What transpired next is unclear, but according to Mrs Proudlock, Steward attempted to rape her. While escaping, she found the revolver that she had presented to her husband on his birthday. She turned and shot Steward twice, she claimed, but the rickshaw driver witnessed Steward stumbling out of the house onto the veranda, where Mrs Proudlock followed shooting at him. Steward collapsed and died, after being shot at six times.

Mrs Proudlock then summoned the police to her residence, who searched the grounds and discovered the dead body of Steward. A Webley revolver was found nearby; all of its bullets had been discharged, with most of them hitting Mr Steward. Witnesses recounted that Mrs Proudlock’s face and chest were covered in blood, and her dress was torn.

Ethel Proudlock confessed to shooting Steward, claiming that he had attacked her and she was acting in self-defence. Her husband testified in court that he believed her and that she had become mentally distressed. In giving her account of the evening, Mrs Proudlock said that Steward had come to visit and found her alone. She had gotten up to get a book when Steward rose, kissed her, and told her: “You’re a lovely girl and I love you.” She claimed that she remonstrated him, tried to call for her servants and switch on the lights; that is when her hand found the gun and she shot him twice as he ran towards the veranda.16

Those who knew Mrs Proudlock referred to her as a quiet woman and noted that she and her husband never quarrelled. Although she claimed self-defence, she was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. However, Mrs Proudlock was subsequently given a free and unconditional pardon as the State Council felt that the effect of having her modesty outraged caused hysteria and made her unconscious of what she was doing, and therefore she was not responsible for her actions.17

Maugham may have changed the location from Kuala Lumpur to Singapore and the names from Proudlock to Crosbie, but many similarities remained. Maugham met a lawyer who was involved in the case and took the facts from the trial. He listened to the gossip that Ethel Proudlock had been having an affair with Steward and shot him in a jealous rage after he tried to call it off. Maugham had extracted the juiciest details and written a scandalous fictional account.

The Backlash

However, it wasn’t just “The Letter” that caused an outcry. Most of the other stories in The Casuarina Tree were based on true stories that Maugham had heard and embellished, leading to scandalous and unflattering portrayals.

To say that the British in the East did not receive this well is an understatement; people were furious. “All that decent-minded people want of S.M. [Somerset Maugham] is a wide berth,” the Malayan Saturday Post wrote in July 1931. “If he ever comes here again he’ll learn that even the tropics can produce frozen mitts. He’s the Man who makes money out of the Muck.”18

Critic Logan Pearsall Smith wrote: “These stories of Maugham’s are all ghastly betrayals of confidences the publication of which has ruined the lives of the hosts who kindly entertained him in the East and confided in him the sad secrets of their frustrated lives.”19

“It is interesting to try to analyse the prejudice against Somerset Maugham, which is so intense and widespread in this part of the world,” the Straits Budget wrote in June 1938. “The usual explanation is that Mr Maugham picks up some local scandal at an outstation and then dishes it up in a short story… the second cause is disgust at the way Mr Maugham has explained the worst and least representative aspects of the European life in Malaya. Murder, cowardice, drink, seduction, adultery… always the same cynical emphasis on the same unpleasant things. No wonder that white men and women who are living normal lives in Malaya wish that Mr Maugham would look for local colour elsewhere.”20

Maugham’s books were deemed notorious enough that Lady Clementi, wife of the Governor of the Straits Settlements, requested a warrant for their immediate removal from library shelves on the grounds of “immorality”.21

This backlash in the East did not appear to bother Maugham. Back in Europe, he did not show any sign of remorse or apology. Instead, he did what he did best: he went in search of more stories.

Maugham Returns

About 30 years later, in 1959, Maugham, returned to Singapore and found the city altered. “The Raffles I knew then was nothing like it is today. The East is a very different world from the one I knew. The people are different. The planters, the government officials and the businessmen who stayed very long stretches here and who, except for infrequent trips, lived the rest of their lives in the East, have all gone. Today, I feel very much a stranger here.”22

People apparently lined up to meet him, inviting him to parties, but Maugham suffered greatly from the heat and reportedly spent most of his time inside the Raffles Hotel in the air-conditioning. He made a surprise visit to a bookshop on Orchard Road and signed his books for a few lucky patrons present.23

Yet, even at the age of 85, Maugham still had the capability to shock and annoy the expatriate community here. Apparently, Maugham and Raffles Hotel manager Frans Schutzman went to the Tanglin Club for lunch one day. Because of their improper attire, they were denied entry. But Schutzman, due to his close relationship with the club’s management and staff, talked his way into the bar. Maugham, provoked and annoyed at not being able to dine, looked around and announced loudly: “Observing these people, I am no longer surprised that there is such a scarcity of domestic servants back home in England.”24

They were both asked to leave immediately and Schutzman lost his membership at the club. It was as if Maugham had to make one more gibe at the expatriate society of Singapore. Maugham left Singapore in 1960. He died in Nice, France, in 1965 at the age of 91.

T.A. Morton is a Singapore-based Irish/Australian writer and a Cambridge graduate. She is co-host of the podcast, The Asian Bookshelf, and author of the upcoming novel, The Coffee Shop Masquerade. In 2020, she was shortlisted for the Bridport Prize for her short work, “Faded Ink”, and the Virginia Prize for Fiction for The Queen, The Soldier and The Girl. Her novel, Someone Is Coming, based on plantation murders in Malaya in the 1900s, was published by Monsoon Books in 2022 and has been optioned for television.

T.A. Morton is a Singapore-based Irish/Australian writer and a Cambridge graduate. She is co-host of the podcast, The Asian Bookshelf, and author of the upcoming novel, The Coffee Shop Masquerade. In 2020, she was shortlisted for the Bridport Prize for her short work, “Faded Ink”, and the Virginia Prize for Fiction for The Queen, The Soldier and The Girl. Her novel, Someone Is Coming, based on plantation murders in Malaya in the 1900s, was published by Monsoon Books in 2022 and has been optioned for television. Notes

-

Klaus W. Jonas, ed., The World of Somerset Maugham: An Anthology (London: Owen, 1959), 97, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/worldofsomersetm0000jona. ↩

-

“Untitled,” Malaya Tribune, 26 April 1921, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Jonas, The World of Somerset Maugham, 101. ↩

-

“Untitled,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 14 May 1921, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Planter’s Tragic Death,” Malaya Tribune, November 13, 1916, 9 (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Planter Murdered,” Straits Times, 24 November 1916, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

William Somerset Maugham, More Far Eastern Tales (Vintage Random House, 2000), 252. NLB has the 2010 version. See William Somerset Maugham, More Far Eastern Tales (Vintage Random House, 2010). (From NLB OverDrive) ↩

-

Maugham, More Far Eastern Tales, 166. ↩

-

William Somerset Maugham, Far Eastern Tales (Vintage Random House, 2000), 247. NLB has the 2010 version. See William Somerset Maugham, Far Eastern Tales (Vintage Random House, 2010). (From NLB OverDrive) ↩

-

Selina Hastings, The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham: A Biography (New York: Arcade Publishing, 2012), 281. NLB has the 2009 edition. See Selina Hastings, The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham (London: John Murray, 2009). (From National Library, Singapore, R 823.912 HAS) ↩

-

Maugham, Far Eastern Tales, 1. ↩

-

Jonas, The World of Somerset Maugham, 107. ↩

-

Maugham, Far Eastern Tales, 13. ↩

-

“Somerset Maugham Interviewed by ‘Malay Mail’,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 25 November 1925, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Maugham, More Far Eastern Tales, 1. ↩

-

“Kuala Lumpur Tragedy: Trial of Mrs. Proudlock,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 9 June 1911, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Mrs. Proudlock Pardoned,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 10 July 1911, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Sparkles,” Malayan Saturday Post, 25 July 1931, 5. (From NewspaperSG). ↩

-

Hastings, The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham, 280. ↩

-

“Anti-Maughamism,” Straits Budget, 9 June 1938, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Noël Coward, The Letters of Noël Coward, ed. Barry Day (Knopf Doubleday Publishing House, 2008), 381. (From NLB OverDrive) ↩

-

Ilsa Sharp, There Is Only One Raffles: The Story of a Grand Hotel (London: Souvenir Press, 1981), 106. (From National Library, Singapore, RSING 647.945957 SHA) ↩

-

“An Old Man Gives the Bookstore Crowd a Pleasant Surprise,” Straits Times, 12 February 1960, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Sharp, There Is Only One Raffles, 108. ↩