The Floods of 1954

The severe floods of 1954 tested community resilience, spurred significant infrastructure improvements and left a lasting impact on Singapore’s flood preparedness measures.

By Darren Seow

It started as a heavy drizzle on the evening of 8 December 1954. Then at 11.20 pm, a torrential downpour began that continued throughout the night, into the next day and then into the night again. In the end, a record 10.9 in (276.86 mm) of rain fell over 24 hours.

It rained so much that at 4.40 pm on 9 December, Kallang Airport was closed to traffic and aircraft on their way to Singapore were diverted to Butterworth in Penang over 800 km away. The rain caused flooding in some 2,500 acres of land, with Bedok being the most severely affected. Other badly flooded areas were Bukit Timah, Grove Estate, Orchard Road, Telok Ayer, Robinson Road, Cecil Street and Anson Road.1

Among those rescued were a mother and her newborn (just 12 hours old), who had to be saved from their flooded home on Aljunied Road. “Rescuers, wading in water chest high in semi-darkness, carried the mother to safety on a stretcher. The baby, curled up in blankets, was carried by a relative,” reported the Straits Times.2

Although floodwaters began to recede on 10 December, many areas were still submerged in water, including Bedok, Potong Pasir, Bukit Timah and Geylang Serai. Floodwaters had entered homes, damaging furniture and personal belongings. “When the people return to their homes they will find plenty of mud and debris. The only people who were happy were children swimming in the ponds,” said City Engineer George Edmond who toured the flood areas that day.3

What the unfortunate people of Singapore did not know at the time was that these scenes would be repeated just a week later.

Thanks to the annual northeast monsoons, December in Singapore is usually a damp month. However, even by monsoonal standards, December 1954 stood out. That month, some 26.81 in (680.97 mm) of rain were recorded, making it the wettest December since 1869.4 And it was not only during the month of December that people here had to endure heavy rains. According to the Public Works Department (PWD), the last quarter of 1954 was the wettest in 85 years. The PWD noted that no less than 53 in (1,346 mm) of rainfall were recorded at the airport.5

As a result of the unusually heavy rainfall that Singapore experienced in the last quarter of 1954, especially in October and December, the island’s drainage systems were overwhelmed, which resulted in extensive flooding. Thousands of people were made temporarily homeless, and farmers lost crops and livestock. The flooding resulted in loss of life as well.6

Following the catastrophic floods of 1954, the government began to take a more holistic approach to flood management. Soon after, the PWD set up a branch dedicated to designing flood alleviation schemes throughout Singapore.

October Floods

The first severe floods of 1954 began on 23 October when a violent three-hour rainstorm lashed Singapore. By 10 am, floodwaters, worsened by the rising tide, had exceeded 4 ft (1.2 m), prompting evacuations from vulnerable locations. The Meteorological Department recorded 4.22 in (107.19 mm) of rainfall between 6.30 am and 9.30 am, with 3.41 in (86.61 mm) falling in the first hour alone.7

As water levels rose, hundreds of motorists were stranded along Bukit Timah, Thomson, Balmoral, Balestier, Newton, Orchard and Changi roads. The flooding along Bukit Timah Road was so severe that traffic between Singapore and Johor had to be rerouted, leaving many government officials residing in Singapore unable to commute to Johor for work. Motorists were also forced to abandon their flooded cars in the middle of the road and wade home.

Houses and huts on low-lying areas along Bukit Timah and Dunearn roads were submerged in more than 4 ft of water. One farmer living off Dunearn Road lost all his belongings, save for a few ducks, when the water reached the roof of his house. The police responded swifty to manage traffic jams and help stranded motorists.8

The October floods also affected 400 homes housing some 3,000 people in the Bedok resettlement village. The area was inundated when the surrounding mud dyke was breached in two places, with one gap spanning 20 ft (6 m). Acting Commissioner of Lands S.G. Burlock later explained that the dykes were not high enough to prevent water from overflowing from the Bedok Road catchment valley. The Straits Budget estimated damages at $250,000 to livestock and food items in the Bedok resettlement village.9

The governor of Singapore, John Nicoll, visited the Bedok resettlement village that night. The village headman told him that 150 acres had been submerged under 3.5 ft (1.1 m) of water, marking the most serious flood in two decades. Experts from the City Council investigated and explained that “water from Tampines and Changi Roads had not been able to flow out to the sea because of the narrowness of the mouth of the Bedok River”.10

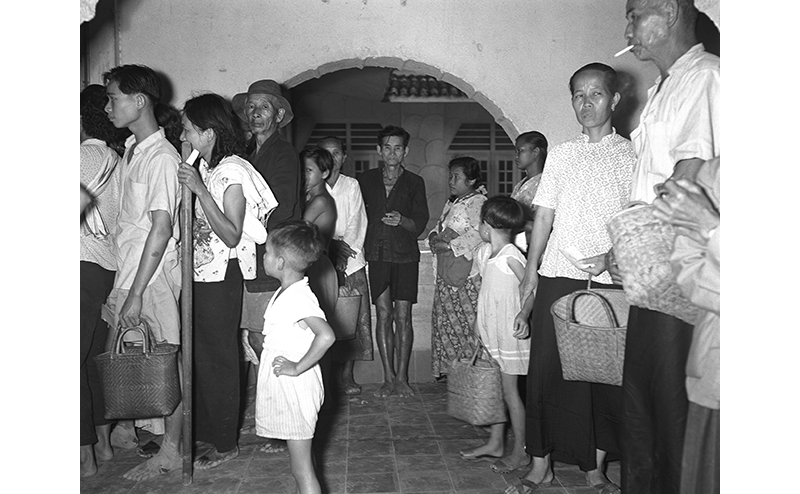

Social welfare officials provided meals to affected villagers and sampans were used to evacuate people from submerged attap huts. Many sought shelter with friends and relatives, while the village school and wayang area were converted into temporary sleeping quarters.

Among those affected was 74-year-old Low Yoke, who had been rescued from drowning. After leaving her home, she “fell into a ditch and was about to disappear under water when two men heard her cries”. Despite her age and her brush with death, she returned by sampan to her waterlogged home later that night to retrieve her wedding ring that she had kept in the bedroom. She was not merely being sentimental though. At least one home had been burgled and the villagers formed a vigilante group to guard the area.11

Torrential Rains in December

A little over a month later, the heavens opened on 8 December and, once again, the Bedok resettlement village bore the brunt of the damage. Farmers in the area were estimated to have suffered losses to crops and poultry amounting to $750,000. Goh Seng Kin, a father of five, said he “lost 120 pigs, 2,000 chickens and 1,500 ducks, estimated at $6,000”. Ho Boon Chiang, who owned the largest plot of land in Bedok, reported $4,800 in damages to vegetables, pigs, poultry and fodder.12 The Social Work Department (SWD) subsequently made relief payments totalling $27,240 to 493 families at $10 per person.13

Unfortunately, another major storm swept through Singapore about a week later. It began raining at 5 am on 16 December and by mid-morning, the rivers had swelled. By midday, kampongs were waterlogged, and eventually Potong Pasir, Bedok and Braddell Road – areas most affected the previous week – were flooded yet again. At Braddell Road kampong, near the swollen Kallang River, hundreds of villagers were evacuated by sampans.14

Once again, the villagers of Bedok were not spared. The floodwaters breached the bund in Bedok resettlement village at 3 pm and despite PWD teams stacking sandbags and reinforcing the bund with poles, water surged through the gaps. Personnel from the Police Reserve Unit deployed five sampans and two rubber boats to help villagers remove their belongings. By 6 pm, however, water levels had risen to 4 ft (1.2 m), and over 250 villagers sought shelter at Bedok Boys’ and Girls’ School, where the SWD provided hot meals.15

By nightfall, thousands of flood victims had been housed in various relief centres across Singapore, where they were provided with hot meals, beverages and clothing. Nicoll visited St Andrew’s School, which had been converted into a mass dormitory. Upon learning that only one float and a few sampans were available for rescue operations in Potong Pasir, he made a radio call instructing the Royal Air Force to despatch evacuation boats.16

In some ways, the people sheltering in the relief centres were fortunate. Five people lost their lives during a rescue operation off Braddell Road on 17 December. At around 2 am, amidst a downpour, the police were evacuating a family of seven – two grandparents, their daughter and four grandchildren – by sampan when the vessel was caught in a strong current and drifted close to the Braddell Bridge over the swirling Whampoa River. The boat struck a submerged sewage pipeline near the bridge, capsizing and throwing all the occupants into the water, which had risen to around 5 ft (1.5 m). Five family members lost their lives: the grandmother, her daughter and three grandchildren; the grandfather and his 6-year-old grandson survived. Clinging onto the overturned boat, the grandfather said he “could hear shouts for help from his wife and daughter but could do nothing to help them”. The capsized sampan, one of 22 deployed by the police, was never recovered, underscoring the dangerous conditions that night.17

As floodwaters steadily receded on 18 December, Nicoll visited the affected areas, starting at Potong Pasir and concluding at Lorong Tai Seng. He pledged support to vegetable, poultry and pig farmers in Bedok, Potong Pasir, Geylang Serai and Lorong Tai Seng to help them rebuild their livelihoods.18

The Bedok Problem

The floods of 1954 had hit the low-lying, coastal Bedok resettlement area particularly hard and the press coined the term “Bedok problem” to describe the issue. The villagers living in Bedok were particularly bitter because they had been resettled there, unwillingly, just two years prior. They had previously been living in Paya Lebar but were forced to move to make way for the new Paya Lebar Airport. Now their farms were being repeatedly flooded.19

After the first round of flooding in December, Legislative Councillor Elizabeth Choy toured the area, and told the press: “They [the farmers] obliged the government by moving from the Paya Lebar area, and it is our duty to see that they do not suffer.” The Straits Times argued that the government had “a moral obligation” to provide “better drainage and other flood prevention measures at Bedok” and a “special responsibility” towards those who relocated from Paya Lebar.20

Even after the floodwaters receded, their problems did not. Shops that had previously extended credit for vegetable seeds and fodder now insisted on cash payments. Pleading for assistance, the farmers sought immediate cash loans from the government to help them start anew. By 20 December, the SWD had disbursed $29,760 in relief payments to 289 families.21

Relief Efforts

Welfare and relief services were provided by the SWD. During the serious flooding incidents in October and December 1954, the SWD was mobilised three times to provide emergency aid in Bedok, Potong Pasir, Braddell Road, Lorong Tai Seng and Geylang Serai. It collaborated with other government departments and voluntary organisations, including the British Red Cross Society, St John Ambulance Brigade and the Singapore Flood Relief Fund Committee.22

Within hours, the SWD had set up temporary shelters and began distributing hot drinks, meals, blankets, clothing, rice and tinned milk. Families also received cash relief payments. The SWD worked with other government teams to register flood victims and conduct relief surveys in affected areas.23

The Singapore Flood Relief Fund, organised by the Straits Times, was formed on 11 December to provide immediate relief to those affected by the floods. Among the first contributors were the American actress Ava Gardner, who was in Singapore at the time, film mogul Loke Wan Tho and the Shaw Brothers, each of whom donated $500.24

Addressing the Singapore Legislative Council on 14 December, Colonial Secretary William Goode announced that the government would contribute $50,000, 10 tons of milk and 4,500 clothing items to the Singapore Flood Relief Fund. Governor Nicoll himself donated $500. Goode also announced that a project to widen and straighten Bedok River (Sungei Bedok) and raise the bunds by 2 ft 6 in (76 cm) between Changi Road and the sea outlet was nearing completion.25

By 29 December, over 30,000 flood victims had received aid from relief centres in all flood-stricken areas. More than $210,250, along with 500 bags of rice, 500 cases of milk, thousands of clothing items, and substantial quantities of kerosene, tinned food and biscuits had been distributed. Fund chairman, F.W. Harvey of the Salvation Army, expressed his gratitude. “There has never been anything like this in Singapore,” said Harvey. “It has been tremendous. During those first terrible days the fund met and broke the brunt of the flood’s destruction. Gifts poured in, distribution was speedy and the co-operation of workers was wonderful.”26

No Compensation for Bedok Farmers

While affected villagers received emergency relief funding, the government would not provide compensation to the Bedok farmers. On 23 December, Under-Secretary J.D. Higham replied to Tan Kang Phuang, chairman of the Bedok Village Flood Relief Committee, that “the principle of compensation could not be accepted”, but assured that the government would “give ‘special treatment’ to victims of the floods” until they could resume crop cultivation and livestock rearing.27

Higham said that $120,000 had been invested in drains, bunds and a sea gate, though he acknowledged that “unfortunately the recent floods were too much for these defences”. “Work is being done now to strengthen and raise the bunds and preparations are being made to cut a straight channel through to the sea for the Bedok River.” He added that the government “regrets that the people of the Bedok resettlement area should have had to endure during recent months such grievous hardship”.28

The farmers were surprised that the government had rejected calls for compensation and on 18 January 1955, 200 farmers and their wives protested, renewing demands for compensation. They claimed their relocation from Paya Lebar to Bedok had been against their will to make way for the new airport. Many farmers were in debt and they urged the government to “put them back [financially] to where they were before the December flood”.29 The following day, Higham reiterated that compensation was not feasible. He explained that the farmers had received relief payments, day-old poultry, fertilisers and vegetable seeds. “This is all we can do,” reported the Straits Times.30

Improving Flood Control

After the severe floods of 1954, the government recognised that a coordinated approach to manage the flood situation in Singapore was necessary. “The need for overall direction and planning of flood alleviation schemes on an Island-wide basis became obvious after the recurrence of serious flooding in December,” noted the PWD’s 1955 annual report. In March that year, a new Drainage Branch within the PWD was set up “whose sole duty it is to undertake surveys and to obtain data for the design of flood alleviation schemes for the Colony”. The chief drainage engineer’s assessment revealed that extensive flood prevention measures were necessary, with projected costs reaching several million dollars.31

A primary initiative centred on Bedok and its resettlement area. The flood control scheme comprised four key elements: an impounding reservoir in the Bedok River valley to regulate water flow; a larger culvert outlet through Changi Road to improve drainage; a 9,400-foot (2,865 m) canal to channel water to the sea; and an elevation of Changi Road to prevent flooding. This $523,000 project was launched on 23 November 1955, with Minister for Communications and Works Francis Thomas in attendance.32 The Bedok Flood Alleviation Scheme was completed in 1956.33

As a small, highly urbanised tropical island, flooding is a perennial issue in Singapore and the government has, over the decades, taken numerous steps to address the problem in different parts of the island. Today, the threat of floods is combined with the challenges of climate change. By 2100, sea levels could rise by up to 1.15 m. This poses a serious threat to Singapore, where about 30 percent of its land lies less than five metres above mean sea level, especially in the East Coast area.34

In response, Singapore has implemented comprehensive defences, including coastal barriers and enhanced drainage systems designed to withstand rising waters. For instance, Marina Barrage, which opened in 2008, functions as both a flood control measure and a reservoir.35 Additionally, naturalised waterways such as those developed under the Active, Beautiful, Clean Waters Programme (launched in 2006) and flood-resilient infrastructure are being constructed to manage excess water.36

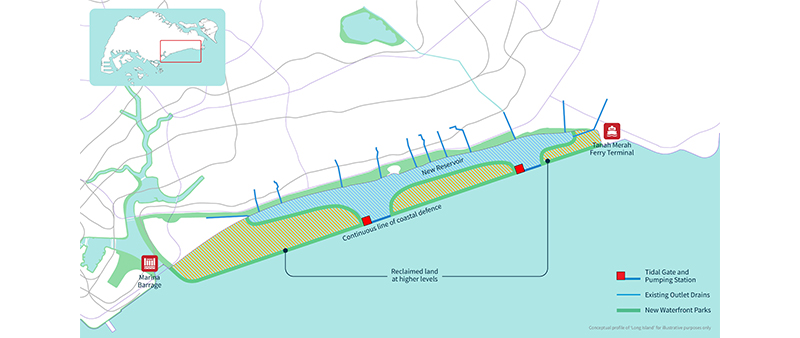

Building on these efforts, then Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong spoke about the “Long Island” concept at the 2019 National Day Rally as a potential solution to protect the East Coast area from rising sea levels. (The concept was first mooted under the 1991 Concept Plan.)37

According to the Urban Redevelopment Authority, “Long Island” would involve reclaiming about 800 hectares of land off the East Coast, potentially in the form of “islands”, to protect the low-lying area from sea level rise and strengthen Singapore’s flood resilience.

Under this plan, land will be reclaimed to a higher level and form a continuous line of defence for protection against rising sea levels, with 12 outlet drains along the coast draining water into a new reservoir with two centralised tidal gates and pumping stations. It will be similar to Marina Barrage and will keep out seawater during high tides and discharge stormwater into the sea during heavy rainfall.

This integrated solution aims to protect Singapore’s coastlines, prevent flooding, increase water resilience, create land for future development and offer recreational opportunities for the East Coast. Speaking at the CNA Summit on 20 February 2025, Minister for National Development and Minister-in-Charge of Social Services Integration Desmond Lee said: “[‘Long Island’] will take many decades to complete; we’ve just started. But we have to start coastal protection work now, because the price of delay or failure will be too high for future generations to bear.38

Darren Seow is a Senior Librarian with the National Library Singapore. His responsibilities include content development, research, and the provision of reference and information services.

Darren Seow is a Senior Librarian with the National Library Singapore. His responsibilities include content development, research, and the provision of reference and information services.NOTES

-

“Monsoon Storm Sweeps Direct into Singapore,” Straits Times, 10 December 1954, 6; “Vigorous Action on Drainage – Goode,” Straits Times, 15 December 1954, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Rain Slackened: They Started on Big Clean-Up,” Straits Times, 11 December 1954, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Floods from the Air,” Straits Times, 11 December 1954, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Singapore, Annual Report 1954 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1954), 228. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.57 SIN). The highest monthly total rainfall for the month of December was 996.3 mm recorded in 2006 at the Buangkok climate station. See “Historical Extremes,” Meteorological Service Singapore, accessed 22 January 2025, https://www.weather.gov.sg/climate-historical-extremes. ↩

-

Public Works Department, Annual Report of the Department of Public Works 1954 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1955), 30. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

Singapore, Annual Report 1954, 6, 118. ↩

-

“Flood Chaos in S’pore,” Sunday Times, 24 October 1954, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Flood Chaos in S’pore”; “500 Rendered Homeless,” Sunday Standard, 24 October 1954, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“$250,000 Flood Havoc,” Straits Budget, 28 October 1954, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Sir John Sees the Havoc,” Straits Times, 25 October 1954, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Farmers Are Angry: ‘Pay or Send Us Back to Paya Lebar’,” Straits Times, 11 December 1954, 6; “Mrs. Choy Tours Bedok and Says: Compensate the Poor Farmers,” Straits Times, 11 December 1954, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Victims Plead for Relief,” Straits Times, 13 December 1954, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Floods Are Worst Yet,” Straits Times, 17 December 1954, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Five Die in Flood Tragedy,” Straits Times, 18 December 1954, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Patrols Watch for Flood Looters,” Straits Times, 19 December 1954, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Farmers Are Angry”; “Bedok Problem,” Straits Times, 14 December 1954, 8; “Opinion: The Bedok Problem,” Singapore Free Press, 23 December 1954, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Mrs. Choy Tours Bedok and Says: Compensate the Poor Farmers”; “Bedok Problem.” ↩

-

“They Are Smiling Again in the Flood Valleys,” Straits Times, 21 December 1954, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Singapore, Annual Report 1954, 118. ↩

-

“The Fund Has Paid Out $101,232,” Straits Times, 22 December 1954, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Fund Opened to Aid Victims of the Floods,” Straits Times, 12 December 1954, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Vigorous Action on Drainage – Goode”; “Relief Steps Today,” Straits Times, 14 December 1954, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Flood Relief Centres Close Down,” Straits Times, 30 December 1954, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“‘Special’ Aid for Farmers at Bedok,” Straits Times, 24 December 1954, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Bedok Farmer Renew Claim: Insist Government Must Pay Compensation for Loss,” Straits Times, 19 January 1955, 2; “Bedok Men Still Want Pay-Out by the Govt.,” Straits Times, 25 December 1954, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Bedok Farmers – It’s Still ‘No’,” Straits Times, 20 January 1955, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Public Works Department, Annual Report 1955 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1955), 2, 30, 40. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 354.59570086 SIN); Singapore, Annual Report 1955, 176. ↩

-

Public Works Department, Annual Report 1955, 40; “Rush Order for Bedok Dam,” Straits Times, 24 November 1955, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Singapore, Annual Report 1956 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1956), 194. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 SIN) ↩

-

“‘Long Island’,” Urban Redevelopment Authority, accessed 15 December 2024, https://www.ura.gov.sg/Corporate/Planning/Master-Plan/Draft-Master-Plan-2025/Long-Island. ↩

-

“Marina Barrage,” PUB Singapore National Water Agency, accessed 15 December 2024, https://www.pub.gov.sg/public/places-of-interest/marina-barrage. ↩

-

Centre for Liveable Cities, “Active, Beautiful, Clean Waters (ABC Waters) Programme,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published August 2019. ↩

-

“‘Long Island’.” ↩

-

Ang Hwee Min, “Long-term Singapore Projects Like ‘Long Island’ Require Political Will: Desmond Lee,” CNA, 20 February 2025, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/cna-summit-desmond-lee-long-island-east-coast-rising-sea-levels-4949151. ↩