Signs of Progress: Deaf Education in Singapore

The first school for the deaf in Singapore was established in 1954, paving the way for deaf education and the development of Singapore Sign Language.

By Rosxalynd Liu and Nathaniel Chew

When pioneering deaf educator Peng Tsu Ying first came to Singapore from Shanghai in the late 1940s, the situation for the Deaf community left much to be desired. Deaf children had no schools and deaf individuals did not have an association to bring them together and represent their interests. In an interview with The Deaf American magazine, Peng recalled that when he first came to Singapore, “I couldn’t find a single deaf person!”1

Determined to change things, Peng would go on to found Singapore’s first school for the deaf in 1954. A pioneer activist for the deaf, the efforts of Peng, and others, eventually led to the formation of the Singapore Deaf and Dumb Association in 1955. This association would later open the Singapore School for the Deaf on Mountbatten Road in 1963 and a vocational institute for the deaf to acquire basic technical skills in 1975.2

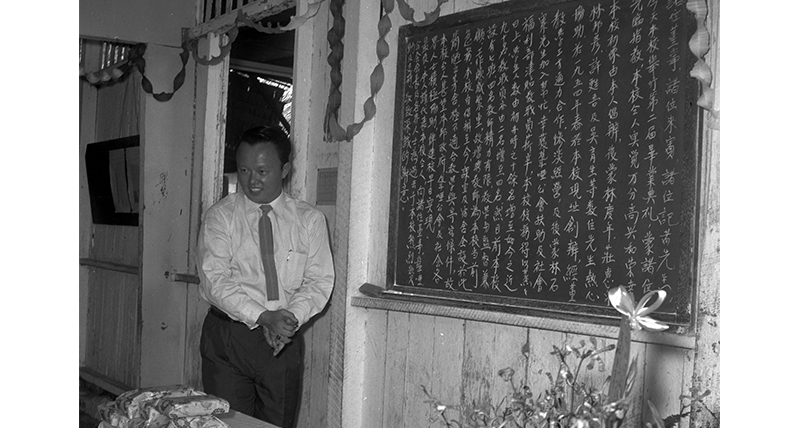

Peng Tsu Ying’s School for the Deaf

Peng and his mother came to Singapore in 1948 to join Peng’s father who was running a greeting card business here. Despite experience as a teacher, on top of book-keeping skills and the ability to correspond in both Chinese and English, Peng, then 21, struggled to find employment – simply because he was deaf.3

Peng was born in Shanghai, China. When he lost his hearing at around age 5, his parents brought him to Hong Kong where he studied at the School for the Deaf and Dumb. During the Japanese Occupation, Peng returned to Shanghai and enrolled at the Chung Wah School for the Deaf for his secondary education. He became well versed in English, Chinese and American sign languages, and also taught briefly at the Hong Kong School for the Deaf and Dumb.4

Intending to put his prior teaching experience to good use in Singapore, Peng enquired at the Department for Social Welfare but was told there was no school for the deaf yet in Singapore at the time. Undeterred, Peng decided to take on this effort himself. He began advertising his services in a local Chinese newspaper which garnered responses from several parents of deaf children. His first class comprised four students, the maximum that he could accommodate in a room in his parents’ home.5

Peng taught using the sign language he had learned in Shanghai, as well as through written Chinese and English. He believed that the deaf could master sign language easily. “You may think the sign language is difficult to learn. To a deaf and dumb child, that extra intelligence to pick up the sign language easily is there,” he told the Straits Times in July 1952.6

As Peng continued to receive applications, he saw the need to make a far greater impact on the local Deaf community and provide them with a proper school as well as the resources to run it. He went door to door seeking donations, successfully collecting more than $3,000 by October 1951.7

“I have been deaf ever since I was a child, and I know how miserable life can be when one is not able to converse, and to make myself understood,” he told the Sunday Standard in July 1951. “That is why I am determined to complete my plan so that the deaf in Malaya can be relieved of their misery, and be given a chance to be useful citizens.”8

It took three years before the Singapore Chinese School for the Deaf opened in 1954 on Charlton Road in Upper Serangoon. Peng became the principal, and together with his wife, Ho Mei Soo, who was also deaf, taught Shanghainese Sign Language at the school.9 The school was renamed Singapore Sign School for the Deaf in 1957.

Despite his deafness, in 1958, Peng participated in motor racing, winning a total of 36 trophies before giving up the sport in 1967 due to financial reasons. He told The Deaf American in 1975: “I can tell you that my main reason for taking part in motor sports was to prove to the hearing world that being deaf is no handicap to being skillful.”10

Peng died on 24 October 2018 from heart failure at age 92 and he was honoured with the Public Service Medal (Posthumous) at the National Day Awards the next year for his selfless dedication to deaf education in Singapore.11

Efforts by the British Red Cross Society

At around the same time that Peng was raising funds for his school, the Singapore Branch of the British Red Cross Society – with the support of the Education Department and Social Welfare Department – started a class for deaf children on Dunearn Road in January 1951, taught by the Manchester University-trained Mrs E.M. Goulden.12

Unlike Peng’s school where classes were taught in sign language, Goulden practised the oral method of instruction, training children in lip-reading and using their residual hearing. This involved using drums to stimulate hearing and enhance rhythm, as well as modern hearing aids when they became available in the mid-1950s. “The chief objective in starting this class is to teach deaf children how to lip-read and to speak in a reasonably clear manner. It is slower but I think the children will be able to pick it up,” she told the Singapore Free Press in an interview.13

Singapore now had two entities conducting classes for the deaf, but demand for places quickly outpaced capacity. Although the Red Cross Society opened up more classes in York Hill in around 1954, there were still more than 100 deaf children on its waitlist in 1955. Peng was also turning down new applicants to his school.

Apart from the lack of capacity, the school buildings themselves left much to be desired: the Red Cross classes were held in makeshift classrooms at a social welfare home and a child welfare centre, while the Singapore Sign School for the Deaf was no more than an attap hut. In May 1958, the Straits Times wrote that the school founded by Peng was a “shabby, (but efficient and spotlessly clean) unpainted, clapboard building”. When a deafness expert from New Zealand visited the British Red Cross School for the Deaf in York Hill in August that year, he described the building as “most unsatisfactory”.14

The Singapore Association for the Deaf and the School for the Deaf

Recognising the need to provide better facilities and resources for the Deaf community, the government initiated the formation of the Singapore Deaf and Dumb Association (now known as Singapore Association for the Deaf [SADeaf]) in August 1955 to take charge of welfare for the deaf and address the educational challenges they faced, and Peng became a member of the association. Its foremost priority was the construction of a new school, for which the government had set aside land.15

A public call was also launched for deaf persons to register themselves with the association – the first attempt to develop a database of Singapore’s deaf population and better understand the scale of services required.16

Several milestones were achieved in deaf education in the following decades. In the 1960s, Malay was added as an option to the curriculum of English and Chinese in both Peng’s school and the Red Cross school.17 In November 1963, the two schools merged to form the Singapore School for the Deaf (SSD) at a new Mountbatten Road campus.18 Peng was appointed principal of the sign section. In 1967, three students from the school became the first deaf children to sit for the Primary School Leaving Examination, taking the same papers as everyone else, and they passed.19

In 1971, the SADeaf began planning for a vocational institute for the deaf beside the SSD so that deaf students could learn basic technical skills. In February 1975, the Vocational Institute of the Singapore Association for the Deaf received its first batch of 50 students who learned skills such as metalwork, woodwork and basic electricity based on the same syllabus used in mainstream vocational institutes.20

After more than 50 years of supporting the Deaf community, the SSD closed in 2017 due to dwindling enrolment as medical advances in screening and the development of assistive devices saw a drop in the number of children with untreated serious hearing loss.21

Today, the majority of deaf and hard-of-hearing students attend mainstream schools with support made available for accessible learning. Designated mainstream schools offer specialised approaches, such as Mayflower Primary School and Beatty Secondary School, where SgSL (Singapore Sign Language) is taught in addition to English. For a small number of students, special-education schools offer additional support. These include Canossian School, which started as a boarding school for deaf children in 1956.22

Studying in Mainstream Schools and Tertiary Institutions

A key policy shift in the 1970s saw deaf students begin to study in mainstream schools. The “open-education policy” sought to expand the number of places available to deaf children, provide more pathways to secondary education and facilitate greater social integration.23

Deaf students in mainstream schools received special support in the form of technical equipment such as speech trainers as well as through resource teachers. One such teacher was Lim Chin Heng, who was himself profoundly deaf. As a resource teacher in Upper Serangoon Secondary School, he would sit in on mathematics classes, using sign language to explain to deaf students who had difficulty understanding the lesson.24

In an interview with the Straits Times in September 1995, conducted through both a sign-language interpreter and handwritten notes, Lim said: “I saw the children progressing under my care, and how they were looking to me as a role model. I realised that they needed someone who could understand them.”25

Despite measures by the SADeaf and the government, educational levels for the Deaf community continued to lag far behind the hearing community. In 1991, there were only 81 deaf students enrolled in tertiary institutions in Singapore and abroad, including the six in the four local universities.26

The challenges facing the deaf and their families were many – the most compelling of which was whether deaf individuals should learn using sign language or English. This decision had far-reaching impacts, such as the need for costly hearing aids and expensive speech therapy, the variety of schools the deaf could attend and even how far they could progress in their education.27

In a letter to the Straits Times in 2004, Emilyn Heng, a mother of two sons with severe-profound deafness, shared the obstacles her sons faced in a mainstream school. “Like all hearing-impaired students, they experienced innumerable difficulties: the inability to follow group discussions, or, on occasion, failing to hear what their teachers had been saying,” she wrote. Despite these challenges, her sons excelled academically. The elder was awarded the Defence Science and Technology Agency Overseas Merit Scholarship to study computer science at Carnegie Mellon University in the United States, and the younger took biology, chemistry and physics and two special papers at National Junior College, and also learnt to play the piano. “Against all odds, the hearing impaired, if they are focused and determined, and have strong parental support, can and will excel,” she added.28

Communication Tools for the Deaf

Before communication or interpretation devices for the deaf became available, communication between the Deaf community and the hearing relied almost solely on interpreters or notetakers, who could either be interpreters from SADeaf or a family member.29 The need for professional interpreters was especially noticeable in the healthcare setting, where signing fluency and health literacy were of paramount importance for interpreting medical consultations accurately.30

There was, and still is, a dearth of professional SADeaf interpreters today. The SADeaf presently has two deaf and six hearing staff interpreters, supported by a group of ad-hoc community interpreters, to serve Singapore’s estimated Deaf community of 500,000 in various settings such as schools, law courts, corporate events and government functions, etc.31

The latter half of the 1980s witnessed a boom in consumer-centric communications technology, such as the tele-typewriter and the pager, providing a much-needed boost. However, it was not until 1991 that communication between the deaf and the hearing was simplified with the proliferation of fax machines in homes, offices and businesses. This increasingly became the Deaf community’s tool of choice when communicating with the hearing community. “I can also send faxes to my banks and other institutions when I need to speak to them without any third-party help,” said teacher Lim Chin Heng.32

Eventually, mobile phones and text messaging facilitated better communication between the deaf and the hearing. Telecommunications providers also recognised the significance of the Short Message Service to the Deaf community, with Singtel and MobileOne introducing customised and cheaper mobile plans.33

In 2006, Singapore’s national broadcaster, Mediacorp, started having real-time English subtitles accompanying the daily evening news on Channel 5, with the exception of the “live news report” section.34 Interpreters were, however, not seen on live national broadcasts until 2012 during the National Day Rally. The broadcast featured live sign language interpreters but without subtitles.35 Nevertheless, it was a step welcomed by the Deaf community, who had had to rely on webcasts for previous rallies and major broadcasts.

A turning point came in July 2013 when the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities was ratified in Singapore. Singapore agreed to ensure that persons with disabilities enjoyed equal human rights and to prohibit discrimination based on disability, which included the Deaf community.36 Since then, the Deaf community has advocated for interpreters and subtitles to be provided in all national broadcasts. Selected theatre and orchestral performances also had sign language interpreters, an encouraging sign that Deaf accessibility was now more than just an afterthought.37

Singapore Sign Language

Over the years, public sentiment towards Singapore’s Deaf community and sign language began to shift. The traditional emphasis on training the Deaf community to hear and speak has evolved into a more holistic appreciation of sign language as a key element of Deaf culture and identity. “Lend them a helping hand and communicate with them by methods they can understand. Let us help the deaf by not insisting that they speak to us,” said Jerry Goh Ewe Hong, president of the SADeaf.38

The sign language used in Singapore today is SgSL, a term first coined by Andrew Tay in 2008, a Deaf interpreter and Singapore Sign Language specialist, citing its importance in helping the deaf recognise and develop their Deaf identity and belonging to the Deaf community as a cohesive whole, besides serving as a common sign language for communication.39

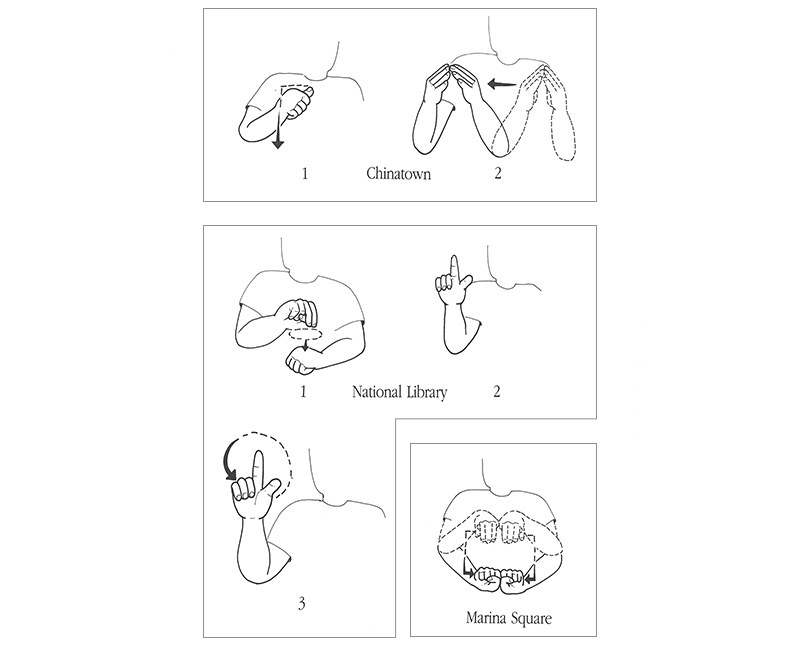

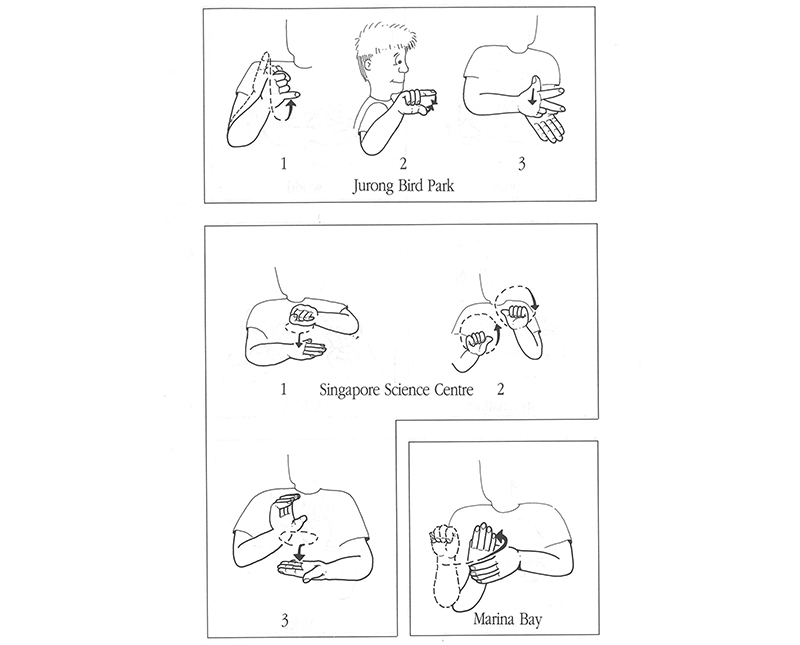

SgSL is a combination of Shanghainese Sign Language, American Sign Language, Signing Exact English (a sign system modelled after the English language, including its grammar and syntax) and locally developed signs. Before SgSL, the earliest form of sign language used in Singapore was Peng’s Shanghainese Sign Language, which he taught in his school. Over the years, it was influenced by other forms such as American Sign Language introduced by Norman C. K. Tsu, a graduate of Gallaudet College in Washington, D.C., and one of Peng’s earliest collaborators at his sign school.40

From 1976, the SSD adopted the Total Communication approach (which integrates various communication methods such as speaking, hearing, fingerspelling, signing, reading, etc.) as an official policy of the SADeaf. But it was Total Communication along with Signing Exact English that made it possible for deaf students at the SSD to follow the regular school curriculum and sit for the Primary School Leaving Examination. This was the predominant language of instruction in the 1980s, used in conjunction with spoken English.41 Subsequently, unique local signs were invented by the Deaf community.

In 1990, these local signs were included in Sign for Singapore, a pictorial guide by the SADeaf to familiarise users and learners with the language and consequently bridge the existing communication gap with the deaf. It contains some 700 signs frequently used in daily life in Singapore, as well as signs for common local references such as Changi Airport, the MRT (Mass Rapid Transit), satay, durian and Deepavali.42

In the 1990s, the SADeaf said it wanted to have sign language recognised as Singapore’s fifth official language. “Making sign language an official language is a long-term plan of the association,” Tan Hwee Bong, executive director of the SADeaf, told the Straits Times in 1994. “The deaf community seeks official recognition for sign language to be on par with the four existing official languages.” It hoped to have “sign language used on television, in banks and other places, and at more public events”.43

At around the same time, the SADeaf noted an increasing number of people taking up its sign language classes for various reasons – from wanting to interact with deaf and hard-of-hearing family members and friends to hoping to volunteer their services to the deaf. Another reason given was the “hip” factor.44

Up to the early 2010s, those who wished to learn SgSL would generally have to do so via one of three ways: at the SADeaf, schools for the deaf, or through informal learning such as videos and learning communities. Another option became available in 2015 when the Nanyang Technological University (NTU) offered SgSL as an elective module.45 Yale-NUS College also started offering sign language as a learning module in 2020, with instructors from the SADeaf.46

The launch of the SgSL Sign Bank in September 2019 to document local signs marked the SADeaf’s first steps towards building a full SgSL dictionary and the eventual recognition of SgSL as an official language in Singapore.47 Signs were collected by first filming Deaf participants producing signs in SgSL sentences. Common signs were then reviewed by a Deaf panel to confirm the signs’ wider recognition, acceptance and usage.48 There are presently more than 700 signs in the sign bank.49 In September 2024, NTU and the SADeaf launched a free e-book on SgSL. It contains common words and uniquely Singapore terms with GIFs, or looping animations, to illustrate how to sign them. This marked the latest effort to boost knowledge of SgSL and raise its visibility.50

The Ministry of Social and Family Development announced in February 2024 that a review on making SgSL Singapore’s official sign language was underway. This move was welcomed by many in the Deaf community. “SgSL’s recognition is very important because it gives us – the deaf community – a true sense of identity,” said Lily Goh, a Deaf arts and music practitioner and performer. “With this recognition, accessibility is enhanced, and standards are increased. Better access will result in better education… such as improving comprehension levels. It could also maybe give us better employment opportunities.”51

In Singapore, the journey of deaf education and accessibility (both physical and digital) is a story of progress, adaptation and advocacy. From the efforts by Peng Tsu Ying, the British Red Cross Society and the SADeaf to set up schools, to the innovative use of new technology, and the community’s push to expand awareness of Deafness and sign language, each milestone marks a step towards a more inclusive society for the Deaf community.

Rosxalynd Liu is Manager of the Central Public Library, Singapore. During her time as Librarian with the National Library, she worked with the General Reference Collection. Her research interests include language, heritage and culture.

Rosxalynd Liu is Manager of the Central Public Library, Singapore. During her time as Librarian with the National Library, she worked with the General Reference Collection. Her research interests include language, heritage and culture. Nathaniel Chew is a Librarian with the National Library Singapore. He works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia Collection, and his research interests lie at the intersection of language and society.

Nathaniel Chew is a Librarian with the National Library Singapore. He works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia Collection, and his research interests lie at the intersection of language and society. NOTES

-

Carl A. Argila, “Peng Tsu Ying – Singapore’s ‘Man for All Seasons’,” The Deaf American 28, no. 4 (December, 1975), 10, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/TheDeafAmerican2804December1975/page/n9/mode/2up. ↩

-

“Deaf and Dumb Society Formed,” Singapore Standard, 27 August 1955, 8. (From NewspaperSG); “History,” The Singapore Association for the Deaf, accessed 28 November 2024, https://sadeaf.org.sg/about-us/history/. ↩

-

“‘2 Deaf-mutes Is My Limit’,” Singapore Free Press, 25 April 1949, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Argila, “Peng Tsu Ying – Singapore’s ‘Man for All Seasons’,” 9; Lee Khoon Choy, “Chinese to Set Up School for the Deaf,” Sunday Standard, 8 July 1951, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“‘2 Deaf-mutes Is My Limit’”; Argila, “Peng Tsu Ying – Singapore’s ‘Man for All Seasons’,” 9; “Two Nodded and They Became Man and Wife,” Straits Times, 31July 1952, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Founder Raises $3,000 for Start,” Singapore Standard, 15 October 1951, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lee Khoon Choy, “Chinese to Set Up School for the Deaf,” Sunday Standard, 8 July 1951, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“First Deaf Recipient of the Public Service Medal (Posthumous),” The Singapore Association for the Deaf, accessed 20 November 2024, https://sadeaf.org.sg/news/%EF%BB%BFfirst-deaf-recipient-of-the-public-service-medal-posthumous/; Tan Tam Mei, “Pioneer Deaf Educator Peng Tsu Ying Dies, Aged 92,” Straits Times, 25 October 2018, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/pioneer-deaf-educator-peng-tsu-ying-dies-aged-92. ↩

-

Argila, “Peng Tsu Ying – Singapore’s ‘Man for All Seasons’,” 9; “First Deaf Recipient of the Public Service Medal (Posthumous).” ↩

-

Tan, “Pioneer Deaf Educator Peng Tsu Ying Dies, Aged 92”; “First Deaf Recipient of the Public Service Medal (Posthumous).” ↩

-

“Lip-Reading Class for Deaf,” Singapore Free Press, 17 January 1951, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Christine Diemer, “The Best Is Still Pitifully Shabby,” Sunday Standard, 18 May 1958, 4; “School for the Deaf Shock,” Straits Budget, 20 August 1958, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Deaf and Dumb Society Formed,” Singapore Standard, 27 August 1955, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Deaf and Dumb Are Asked to Register,” Singapore Standard, 12 November 1955, 2. (From NewsppaerSG). ↩

-

“Deaf Children Learn National Language,” Straits Times, 1 April 1960, 5; “They Will Now Teach Malay in School for the Deaf,” Singapore Free Press, 18 July 1961, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Modern Facilities for Teaching Deaf Children,” Straits Times, 24 November 1963, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Silent 3’s Secret: First Deaf Children for Exam,” Straits Times, 18 November 1967, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Courses for 50 Deaf Students,” New Nation, 28 February 1975, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Amelia Teng, “Singapore School for the Deaf to Close Due to Dwindling Enrolment,” Straits Times, 17 September 2017, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Hearing Loss and Inclusive Education,” Ministry of Education, 8 November 2022, https://www.moe.gov.sg/news/parliamentary-replies/20221108-hearing-loss-and-inclusive-education; “Our Journey,” Canossian School, accessed 23 December 2024, https://canossian.edu.sg/about-us/our-journey; Elisha Tushara, “Canossian School and Canossa Catholic Primary School to Combine in 2025,” Straits Times, 26 January 2024, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/canossian-school-and-canossa-catholic-primary-school-to-combine-in-2025. ↩

-

Goh Ewe Hong, “Untitled,” Straits Times, 3 February 1972, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Yeow Pei Lin, “Deaf Teacher Honoured for His Helping Hands,” Straits Times, 25 September 1995, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Few Deaf Pupils Enter Universities,” Straits Times, 9 March 1999, 33. (From NewspaperSG); More Hearing-Impaired Students Enter Universities,” Singapore Management University, 4 September 2012, https://news.smu.edu.sg/news/2012/09/04/more-hearing-impaired-students-enter-universities. ↩

-

Dorothy Ho, “The Mother Who Wouldn’t Give Up,” Straits Times, 9 March 1999, 33; Chang-Tang Siew Ngoh, “These Deaf Children Are Most at Risk,” Straits Times, 27 January 2004, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Emilyn Heng-Sim Ai Tin, “Parents Can Help Deaf Children Excel,” Straits Times, 21 January 2004, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chua Hillary, “Healthcare Access for the Deaf in Singapore: Overcoming Communication Barriers,” Asian Bioethics Review 11, no. 4 (30 November 2019): 377–90, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s41649-019-00104-3. ↩

-

Jay M. Brenner, et al., “Use of Interpreter Services in the Emergency Department.” Annals of Emergency Medicine 72, no. 4 (October 2018): 432–37, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0196064418304311. ↩

-

“FAQ on Sign Language Interpreters,” Singapore Association for the Deaf, accessed 26 November 2024, https://sadeaf.org.sg/faq-on-sadeaf-and-about-the-deaf-and-hard-of-hearing/faq-on-sign-language-interpreters/; “FAQ on Number of Deaf in Singapore,” Singapore Association for the Deaf, accessed 26 November 2024, https://sadeaf.org.sg/faq-on-sadeaf-and-about-the-deaf-and-hard-of-hearing/faq-on-number-of-deaf-in-singapore/; “Sign Language Interpretation,” Singapore Association for the Deaf, accessed 26 November 2024, https://sadeaf.org.sg/service/interpreting/. ↩

-

“SMS Phone Deal for Deaf,” Today, 17 August 2001, 4; “Phones for the Deaf,” Straits Times, 15 December 2000, 20. (From NewspaperSG). ↩

-

Phoebe Tay and Bee Chin Ng, “Revisiting the Past to Understand the Present: The Linguistic Ecology of the Singapore Deaf Community and the Historical Evolution of Singapore Sign Language (SgSL),” Frontiers in Communication 6 (January 2022), https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/communication/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2021.748578/full. ↩

-

Goh Yan Han, “10th Consecutive National Day Rally to Have Sign Language Interpreter As S’pore Aims for More Accessible Content,” Straits Times, 23 August 2022, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/10th-consecutive-national-day-rally-to-have-sign-language-interpreter-as-spore-aims-for-more-accessible-content. ↩

-

Hillary Chua, “Healthcare Access for the Deaf in Singapore: Overcoming Communication Barriers,” Asian Bioethics Review 11, no. 4 (30 November 2019): 377–90, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7747252/. ↩

-

Mayo Martin, “Loud and Clear,” Today, 25 May 2015, 34. (From NewspaperSG); Cheryl Lin, “Music for the Deaf, Theatre for the Blind: How the Arts Is Catering to People with Disabilities,” CNA, 30 December 2021, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/music-theatre-arts-catering-deaf-blind-people-disabilities-2378106. ↩

-

“Why Many Deaf Children Are Denied Schooling,” Straits Times, 22 September 1976, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Andrew Tay,” Equal Dreams, accessed September 2, 2024, https://equaldreams.sg/member/andrew-tay/. ↩

-

“A Teacher for the Deaf,” Singapore Standard, 23 November 1955, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chua Tee Tee, “Methods of Teaching Deaf Children in Singapore and Malaysia,” Teaching and Learning 11, no. 2 (1991): 12–20, https://repository.nie.edu.sg/entities/publication/6c5765cd-44e7-45d9-bc85-01451bde46c2/details. ↩

-

“Sign Language Book to Hit Stands Soon,” Straits Times, 1 October 1990, 16. (From NewspaperSG); Sign for Singapore (Singapore: Times Books International, 1990). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 419 SIG) ↩

-

Janet Ho, “Recognise Sign Language, Says Deaf Association,” Straits Times, 18 February 1994, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Leow Si Wan, “More Signing Up to Learn Sign Language,” Straits Times, 3 October 2009, 48. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Syarafana Shafeeq, “New E-book on Singapore Sign Language Among Latest Efforts to Raise Visibility of Local Signing,” Straits Times, 20 October 2024, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/new-e-book-on-singapore-sign-language-among-latest-efforts-to-raise-visibility-of-local-signing; “Singapore Sign Language Classes,” Nanyang Technological University, accessed 28 November 2024, https://www.ntu.edu.sg/cml/languages/singapore-sign-language/singapore-sign-language-classes. ↩

-

“Sign Language Module Offers Students Unique Learning Opportunity and Insight on Deaf Culture,” Yale NUS College, 31 March 2020, https://www.yale-nus.edu.sg/story/31-march-2020-sign-language-module-offers-students-unique-learning-opportunity-and-insight-on-deaf-culture/. ↩

-

“SgSL Sign Bank Launched!,” The Singapore Association for the Deaf, accessed 28 November 2024, https://sadeaf.org.sg/sgsl-sign-bank-launched/. ↩

-

“FAQs,” SgSL Sign Bank, accessed 28 November 2024, https://blogs.ntu.edu.sg/sgslsignbank/faqs/. ↩

-

“List of Signs,” SgSL Sign Bank, accessed 28 November 2024, blogs.ntu.edu.sg/sgslsignbank/signs/. ↩

-

Syarafana Shafeeq, “New E-book on Singapore Sign Language Among Latest Efforts to Raise Visibility of Local Signing.” ↩

-

Darrelle Ng, “Deaf Community Welcomes Study on an Official Sign Language in Singapore, But Educational Challenges Remain,” CNA, 2 February 2024, http://channelnewsasia.com/singapore/deaf-sign-language-sgsl-national-education-school-challenges-4094101. ↩