A Tale of Two Cities: Singapore Through the Lens of P.S. Teo and Ronni Pinsler

The photographs of P.S. Teo and Ronni Pinsler of a bygone Singapore form part of the National Archives of Singapore’s 5.5-million strong collection.

By Lu Wenshi and Ronnie Tan

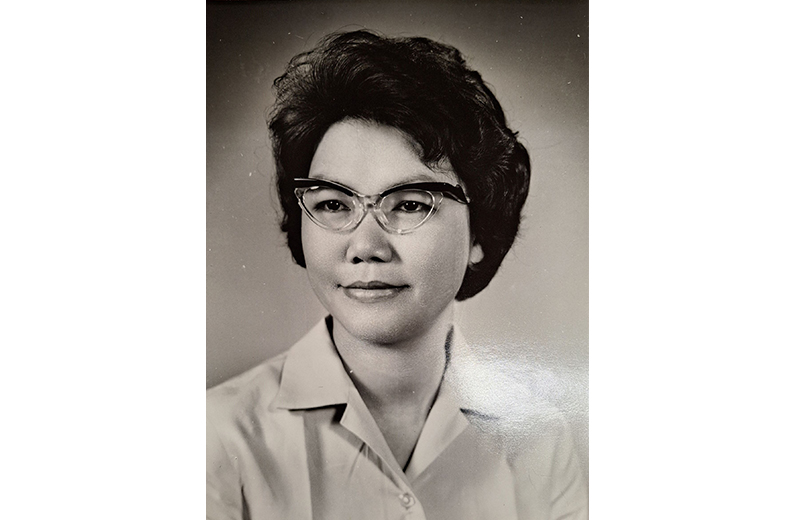

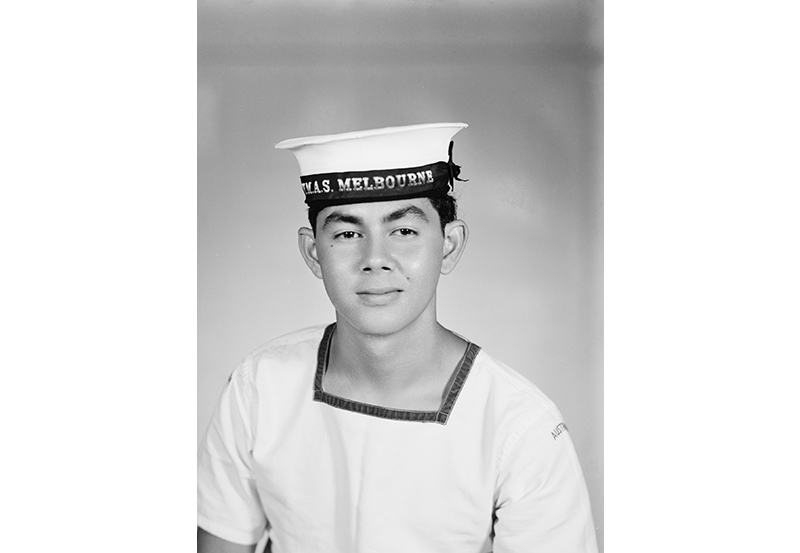

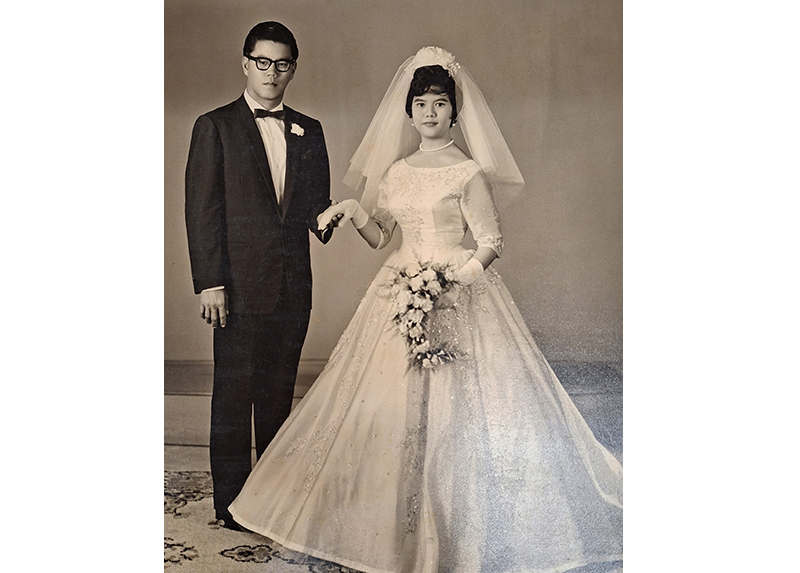

Photographs of people generally fall into one of two categories. The first is a carefully staged, posed photograph of the subject, typically in controlled situations. The other is a candid shot of the subject in action, whether he or she is aware of the photographer or not. While these approaches have very different outcomes, both types of photographs in the National Archives of Singapore (NAS) are of interest to historians and history enthusiasts.

The former category of photographs is found in the Studio De Luxe Collection, captured by P.S. Teo, while the latter category makes up the bulk of the Ronni Pinsler Collection. These photos are available on Archives Online, the portal of the NAS providing access to photographs, maps, building plans, oral history interviews, audiovisual recordings and other archival records of Singapore.

P.S. Teo, Studio Photographer

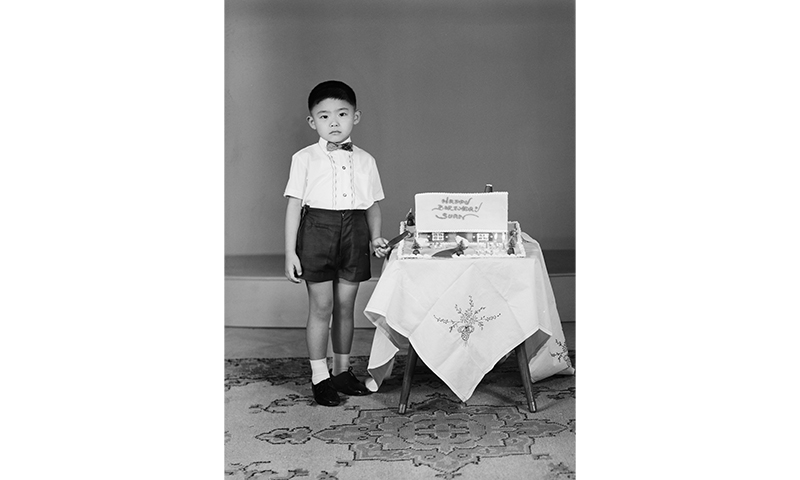

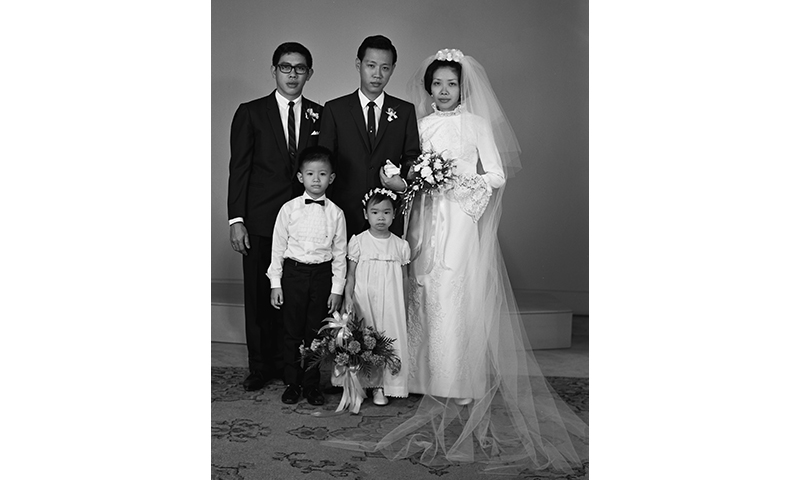

Before the advent of compact cameras, the photo studio was where most people were photographed, especially if portraits were needed. An individual might want or need a portrait, newlyweds would typically desire a wedding photograph to display at home, and families would take photographs, perhaps to mark a momentous event like a graduation or an addition to the family.

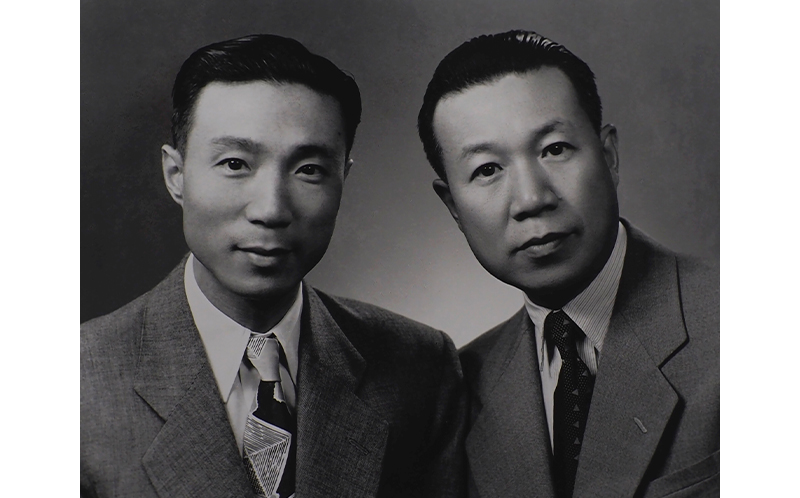

In 2007, the family of the late award-winning photographer Teo Poh Seng donated 26,000 negatives and photographs to the National Archives. Teo Poh Seng, or P.S. Teo as he was professionally known, was famous for capturing artistic black-and-white portraits of prominent people in Singapore, including supreme court judges, politicians, businessmen and local artistes.1

Born in 1930 in Sibu, Sarawak, Teo was the eldest of eight children. His father Teo Chong Kim, also known as Teo Chong Khim or C.K. Teo, and mother Lim Geok Lian relocated to Singapore in 1934.2

The family lived in Outram. Teo Chong Kim worked as a manager at the Great World Amusement Park on Kim Seng Road until the outbreak of World War II. The Teo family then moved to Pek San Teng village off Thomson Road where the senior Teo became a farmer during the Japanese Occupation.3

After the war, Teo Chong Kim found work as a clerk at Jazz Studio along North Bridge Road. When Jazz Studio expanded and set up Studio De Luxe at 33 Stamford Road, which opened for business on 16 February 1946, Teo Chong Kim became its manager. The studio provided both indoor and outdoor photography services. (The premises of the studio is today part of Hotel Kempinski.)

P.S. Teo was enrolled at St Anthony Boys’ School and then at Anglo-Chinese School, Coleman Street. As a schoolboy, he was already helping out at Studio De Luxe. Besides doing odd jobs such as sweeping and washing the floor, Teo also observed and assisted the chief photographer and his father, who handled the lighting.

After completing his secondary school education in 1949, Teo joined his father at Studio De Luxe. Not long after, the owner of Studio De Luxe migrated to Taiwan and sold his share in the business to Teo’s father.4

Encouraged by his father, Teo took up a correspondence course at the Alpha School of Photography in London in 1952. He also subscribed to photography magazines and read books by well-known photographers such as Yousuf Karsh and Francis Wu, who both specialised in portraits; Wellington Lee, who did portrait and commercial work; and renowned landscape photographer Ansel Adams. Teo also participated in photography competitions and won awards.

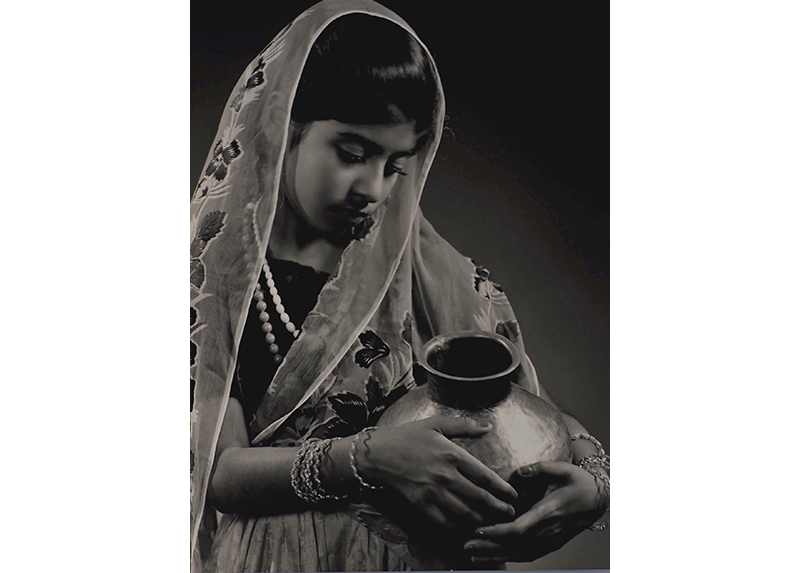

Teo was a master of his trade.5 He started taking photographs of notable people when he was only in his early 20s. He directed people like prominent businessmen, judges and politicians on how to pose.6 He took portraits of well-known personalities of the time – colonial judges, sultans, presidents, prime ministers and artistes including Rathi Karthigesu, a well-known classical Indian dancer and wife of Justice M. Karthigesu, a former High Court judge. Wedding photography was his specialty. The wedding photograph of Neo Chwee Kok, who, to date, is the only local swimmer to have won four gold medals in the Asian Games (an achievement that took place in 1951), is included in Studio De Luxe’s collection with the NAS.

As the eldest son, Teo set aside his personal ambitions to help care for his younger siblings. “He had worked so hard throughout his life, taking care of his parents and siblings,” said his siblings in the book, P.S. Teo, Photographer (1930–2005). “He did not take any holidays and never visited his country [sic] of birth, Sarawak… [w]hile we, his siblings received tertiary and professional qualifications with his financial support and went through the usual education system.”7

Studio De Luxe remained at Stamford Road for four decades until Teo’s father died following a short illness in 1986. As the property was rent-controlled and under his father’s name, Teo could not continue operating there. Seeing how much the business meant to him, his siblings pooled their resources together to relocate the studio to 17C Lorong Liput in Holland Village, where he worked till his health failed him. So committed was he to his craft that even when he was very ill with terminal cancer, his “[p]rofessionalism and responsibility to his clients were uppermost on his mind”.8

Teo, who never married, died on 11 February 2005, at the age of 75.

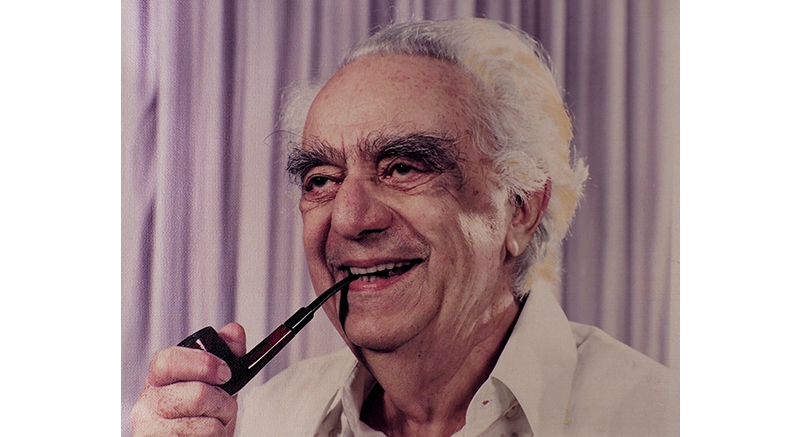

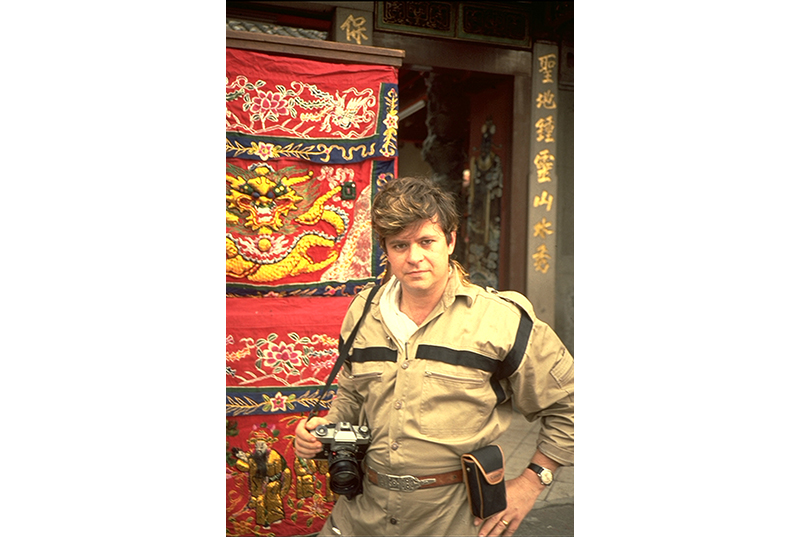

Ronni Pinsler, Street Photographer

While the Studio De Luxe Collection consists of studio photographs, the Ronni Pinsler Collection is very different. Pinsler was a diamond trader by profession who started taking photographs as a hobby.

Born in 1950 in Singapore to British parents of Romanian descent, Pinsler’s collection of more than 16,000 photographs of everyday scenes in Singapore from the 1970s to the mid-1990s have been on permanent loan to the NAS since the 1990s. He also meticulously captioned each photograph, a process which took him over a year.9

Pinsler’s early life in Singapore was interrupted by his studies in England at age 9, before returning to work in his family’s diamond trading business when he was 21. He then got to know Hans Hoefer, a travel guide writer and photographer, who taught him the basics of creative photography.10

Armed with an eye for detail and his trusty Leica camera, Pinsler travelled around the island, visiting Chinese temples and documenting the street scenes of Singapore. “I always kept the camera in my bag with the diamonds and cash I collected from my day job. I would stop by temples and just kaypoh [Hokkien for ‘busybody’],” he said in an interview with the Straits Times in 2024.11

Pinsler’s collection includes significant photographs of Chinese customs, festivals and the birthdays of various gods. He attributed his interest in all things Chinese to Ah Toh, the Cantonese majie (domestic helper) employed to look after him. As his parents travelled a lot for work, he would accompany Ah Toh to her village in Changi to attend festivals and temple celebrations.12

Many of Pinsler’s photographs feature Taoist rituals, given his fascination for the subject. In 1978, while on a visit to the temple at the Delta Road housing estate, he saw spirit mediums (tangki in Hokkien) in a trance including one who had his back pierced with spears as Nezha San Tai Zi, the Third Prince (哪吒 三太子), at the birthday procession of Taoist deity Guan Gong (关公). Pinsler managed to capture the unfolding scenes, allowing viewers a peek into the lives and practices of these spirit mediums.

His rich knowledge of the extensive Taoist pantheon and his ability to identify the many deities added value to his collection of photographs. Pinsler also captured trades of yesteryear such as the samsui women, night soil carriers, karung guni (rag-and-bone) men and trishaw riders.

Unlike studio photography, street photography captures spontaneous moments that are not posed, with the subject often unaware that they are being photographed. A photograph of samsui women on a lorry was taken from Pinsler’s car while he was at a traffic stop. He said that samsui women were mostly too shy to have their images taken, and recalled that one in front covered her face as soon as she saw his camera.13

Pinsler occasionally had to literally chase people to get a shot. In 1981, Pinsler was at a goldsmith shop in the Arab Street area for work when he spotted a night soil carrier by chance. These were people who collected human excrement (known euphemistically as “night soil”) from homes in buckets for disposal at designated areas or for use as fertiliser on farms and plantations. Pinsler ran after the man to capture the shot and remembers the smell to this day.14

Pinsler’s photographs provide a raw and intimate look into the sights and scenes of a Singapore that no longer exists. For his invaluable efforts to document Singapore’s history through photography and for the permanent loan of these photographs to the NAS, he received the prestigious Supporter of Heritage award from the National Heritage Board in 2010.15 (The NAS was then under the management of the National Heritage Board. It became an institution of the National Library Board in November 2012.)

The Photograph Collection in Archives Online

Both the Ronni Pinsler and Studio De Luxe collections can be accessed on Archives Online, which has more than 2.3 million photographs about Singapore. These photographs were either transferred or donated to the NAS over time. One of the oldest photos is that of Captain William G. Scott, the Harbour Master Attendant and Postmaster of Singapore in 1836.

The NAS has about 600 different photograph collections. Some of these come from private collections from personalities such as Yusof Ishak, Singapore’s first president, and Lim Nang Seng, the sculptor of the Merlion. There are also collections from local and foreign institutions like the Ministry of Information and the Arts (now Ministry of Digital Development and Information) and the National Archives of Australia.

Members of the public are encouraged to explore all these photographs on Archives Online and also check out what’s featured on our new virtual photographs curation.

The writers are also grateful to Ronni Pinsler for generously sharing his experiences in taking the photographs showcased in this article.

What guides the National Archives of Singapore’s collection policy on photographs?

The National Archives of Singapore (NAS) will collect and preserve records, including photographs, based on the following criteria:

· Their value to the Singapore government in terms of policy, governance and decision-making, particularly those that document the thinking process behind policies and programmes, like photographs of the Singapore River Clean-up that began in the 1970s.

· Their value to the nation, those pertaining to Singapore as a sovereign state and the international agreements which Singapore is party to, such as photographs of the visits of foreign heads of state to Singapore.

· Their value to the community, with reference to preserving social memories, including photographs of past events and scenes of Singapore in bygone days.

· Their value to the individual, with a view to safeguarding individual rights, such as marriage records.

Processing print format photographs, negatives and slides

Photographs – be they prints of various sizes, slides (also known as positives) or negative formats – are first assessed to determine if they could be preserved. If these are in good condition, they would be described and stored in photograph sleeves and archival boxes for the Photographic Activity Test (PAT), which assesses the potential for materials to cause damage to the photographs over time. Those that pass the PAT are barcoded and fumigated, and sent to climate controlled storehouses called repositories for preservation. The temperature and humidity levels in the repositories are set at 19 °C ± 2 and 50% ± 5%, which are the best conditions for their long-term preservation.

How are the photographs made available online?

After the physical photographs have been recorded and stored in archival quality sleeve protectors, the photographs are sent for digitisation and the metadata uploaded onto the NAS’s Archives Online system. Each photograph is given a unique media image number for ease of identification and to facilitate retrieval.

Where do the photographs come from?

The NAS receives photographs through transfers from two sources: namely government agencies and donations from private individuals and organisations. The Ministry of Digital Development and Information and its predecessors – the Ministry of Culture, the Ministry of Culture and Information, and the Ministry of Information and the Arts – are the biggest contributors of photographs, with about 200,000 transferred to the NAS each year.

Lu Wenshi is a Senior Manager with the National Archives of Singapore, who has an innate interest in photographs, old and contemporary. She oversees the speeches and press release collections, content curation and crowdsourcing for the Archives Services department.

Lu Wenshi is a Senior Manager with the National Archives of Singapore, who has an innate interest in photographs, old and contemporary. She oversees the speeches and press release collections, content curation and crowdsourcing for the Archives Services department. Ronnie Tan is a Senior Archivist with the National Archives of Singapore, who has a keen interest in photography and history. He was previously a Senior Manager (Research) with the National Library Singapore, where he conducted research on public policy, library-related topics as well as historical research, including the Malayan Emergency (1948–60) and military history.

Ronnie Tan is a Senior Archivist with the National Archives of Singapore, who has a keen interest in photography and history. He was previously a Senior Manager (Research) with the National Library Singapore, where he conducted research on public policy, library-related topics as well as historical research, including the Malayan Emergency (1948–60) and military history.Notes

-

P.S. Teo was awarded the Associateship of the Institute of British Photographers (AIBP) for portrait photography in 1956. He became an Associate of the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain (ARPS) in 1957, and was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts (FRSA) in 1958. See Teo Soh Lung, ed., P.S. Teo, Photographer (1930–2005) (Singapore: Word Image, 2020), 8. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 770.92 P) ↩

-

Teo, P.S. Teo, Photographer (1930–2005), 10. ↩

-

Teo, P.S. Teo, Photographer (1930–2005), 10, 64. ↩

-

Teo Yeow Seng, oral history interview by Claire Yeo, 8 June 2007, Reel/Disc 4 of 5, 20:30–20:57; Teo, P.S. Teo, Photographer (1930–2005), 13, 14, 18. ↩

-

Teo, P.S. Teo, Photographer (1930–2005), 18–19, 22, 27. ↩

-

Teo, interview, 8 June 2007, Reel/Disc 4 of 5, 07:55–08:21. ↩

-

Teo, P.S. Teo, Photographer (1930–2005), 7. ↩

-

Teo, P.S. Teo, Photographer (1930–2005), 7, 33. ↩

-

“Why the Chinese Do What They Do,” Straits Times, 24 January 1987, 1. (From NewspaperSG); Jessica Novia, “Treasure Hunters: Meet the Collectors Archiving Singapore’s History,” Straits Times, 12 August 2024, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/treasure-hunters-meet-the-collectors-archiving-singapore-s-history. ↩

-

Novia, “Treasure Hunters: Meet the Collectors Archiving Singapore’s History.” ↩

-

Novia, “Treasure Hunters: Meet the Collectors Archiving Singapore’s History.” ↩

-

Novia, “Treasure Hunters: Meet the Collectors Archiving Singapore’s History.” ↩

-

Ronni Pinsler, email interview, 24 February 2025. ↩

-

Ronni Pinsler, email interview, 24 February 2025. ↩

-

Novia, “Treasure Hunters: Meet the Collectors Archiving Singapore’s History.” ↩