Dutch Burghers in British Malaya

A murder mystery sheds light on the little-known story of the Ceylonese pioneers from the Dutch Burgher community who joined the subordinate government ranks in British Malaya.

By Yorim Spoelder

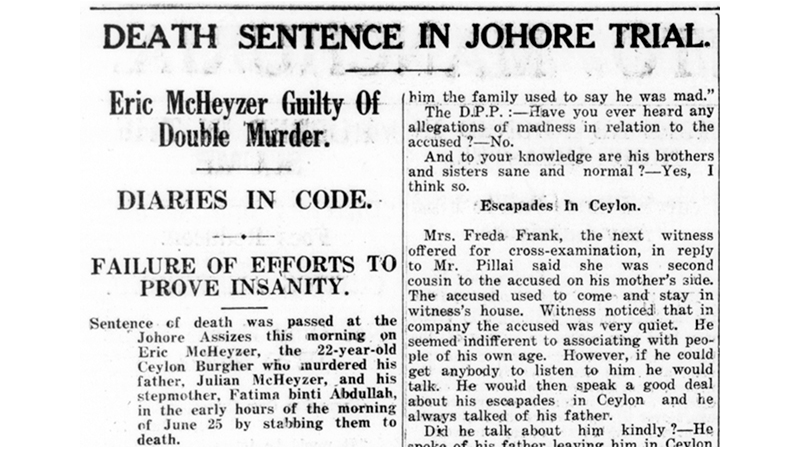

In the early hours of 25 June 1932, shortly before sunrise, a young man wearing a shirt and trousers drenched in blood calmly strolled into the police station in Johor Bahru. Eric Edwin Cecil McCarthy McHeyzer, age 22, was to all appearances composed and in full command of his senses. However, all was not well, and he reported that he had been the victim of a stabbing while trying to catch some sleep in the bandstand near the sea front. The police officers duly investigated the spot mentioned by Eric, but reported that they did not find any traces of blood.1

A little while later, the police were alerted to a double homicide in a house along Jalan Mustapha. The victims, it soon turned out, were Eric’s father Julian McCarthy McHeyzer, a Dutch Burgher and long-time Johor resident, and his Malay wife Fatima Abdullah. Julian had been stabbed repeatedly inside the house, while Fatima was found on the neighbour’s verandah where she had succumbed to similar wounds shortly after being attacked.2

A Sensational Murder Case

Eric was unable to provide a compelling alibi and was promptly arrested in relation to the murders. He claimed innocence but showed suspiciously little emotion. The next day, neighbours of the couple came forward with incriminating evidence. Mrs Ng Chye Hock reported how she had been woken up by unusual noises and shouts of help from Fatima who had repeatedly uttered “Nonya, Nonya, tolong” (in this instance, “nonya” is a respectful term for a married woman, and “tolong” means help) until all went eerily quiet. Furthermore, she had seen a man jumping out of the window and hastily making his way in the direction of the road before vanishing into the dark Malayan night.3

Another witness, the deceased couple’s Javanese cook, reported how Eric had one week earlier shown up late in the evening demanding dinner. While she was preparing the food, she overheard the accused mumbling to himself, “I am going to kill my father. He will die or I will die.”4 Disturbed by these ominous words, she peeked into the room, and was shocked to find the accused fondling a kris and cutting himself in the hand.5

This alone might have been sufficient evidence to convince the court of Eric’s guilt, but in the absence of a confession, it remained unclear what could have compelled Eric, who had visited his father numerous times over the past months, to commit such an atrocious crime. During the first phase of the trial, various fruitless speculations about Eric’s mental health, including somewhat bizarrely his alleged “lack of sex-appeal”, the formation of his forehead and the way his hair grew, had been brought forward to account for the crime. But medical experts found no evidence of any disordered state of mind, and Eric himself made a calm statement from the dock claiming innocence. Then another startling piece of evidence emerged which revealed a motive. It turned out that the accused had kept a diary which he had hidden in a locked suitcase bearing his initials.6

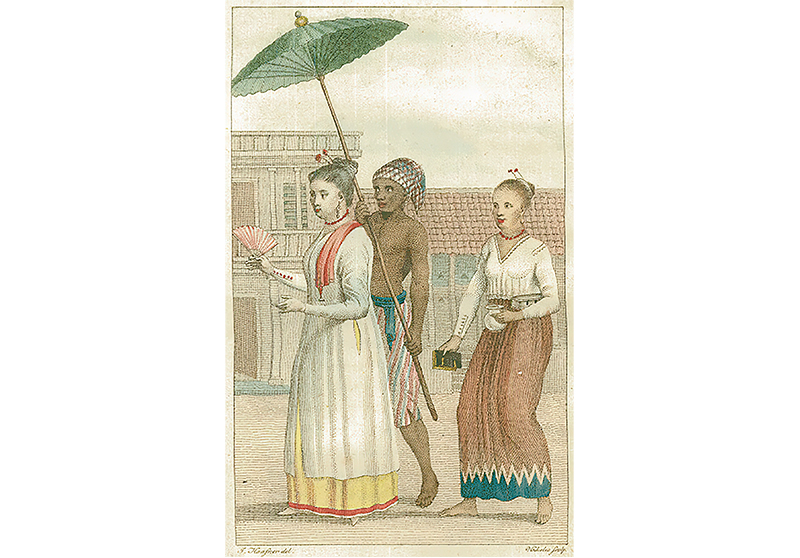

The diary related how Eric had been sacked from the Ceylon Government Railway in 1930, after which he failed to find gainful employment and became homeless. Eric would have been barely 20 at the time, but he found himself “totally down and out”.7 He had grown up in a broken Dutch Burgher family as the eldest son of Julian McHeyzer and Claire Pate, who had three other children. Eric belonged to the small but influential mixed-race community who claimed descent to the Dutch soldiers and clerks of the Dutch East India Company. Established in 1602, the company had ruled Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) from 1640 until the British gained control of the island in 1796.8

When Eric was six years old, his father abandoned his wife and family and moved to Malaya where he found work as a teacher, converted to Islam, and married a Malay wife, Fatima. Now a grown man himself and faced with limited opportunities in Ceylon, Eric remembered his father’s journey of reinvention, and perhaps on a whim of inspiration and opportunism, managed to get funds from friends to travel by steamer to Singapore in April 1931.9

Once in Malaya, he succeeded in locating his father, but did not receive the warm welcome and support he had anticipated. Although he occasionally stayed with his father and Fatima, Eric became increasingly resentful of how he was being treated. He had told his father about his circumstances and sought his help to find employment but “got kicked” instead. He also did not forget how his father “had done nothing for my sisters and brothers” and had not “spent a cent on us for our education”.10 This was a striking accusation in light of the fact that education had long been the realm in which Dutch Burghers excelled, bringing forth luminaries such as the influential lawyer and journalist Charles Ambrose Lorenz (1829–71) and Sir Richard Francis Morgan (1821–76), the Chief Justice of Ceylon who famously became one of the first Asians in the British Empire to receive a knighthood.

According to various witnesses, Julian had, in turn, complained about a lack of respect from Eric who appeared out of the blue. He had planned to take out a loan of $75 to cover Eric’s boat passage back to Ceylon.11 However, before this could materialise, the resentful son’s wounded pride and filial hate drove him to a desperate act of vengeance for which he would pay with his life. The Straits Times, which covered the progress of the trial in a series of colourful articles, soberly reported on 28 October 1932 that “the 22-year-old Ceylon Burgher, who was found guilty of the murder of his father and stepmother in Johore on June 25 was hanged”.12

Migration to Malaya

This tragic and gruesome story sheds light on a broader transimperial conduit of migration between Ceylon and British Malaya. The McHeyzers were not the only Dutch Burghers who crossed the Bay of Bengal in search of better employment opportunities or a new life.

Their story is, however, rarely noticed by historians for two reasons. On the one hand, the number of Dutch Burghers that settled in British Malaya was fairly small and their presence too scattered to evolve close-knit community structures. On the other hand, the few excellent studies on the Dutch Burgher community in the colonial period rarely extend their purview beyond South Asia. As a result, the transimperial lives of Dutch Burghers who left Ceylon have not been well documented. However, Dutch Burghers were well represented among the subordinate ranks of the colonial government, which actively recruited Ceylonese clerks for positions in the Federated Malay States and Straits Settlements in the late 19th century.

The first wave of Ceylonese Burghers who moved to British Malaya in the 1880s and 1890s were actively recruited by local government agencies to fill lower-level positions in the railways, Public Works Department or medical service. These posts had been hard to fill as very few Europeans could be induced to move to often isolated or malaria-infested regions to take up employment offering little financial reward. The local governments thus cast their nets wider and found that Ceylonese Burghers, who were well educated and proficient in English, were excellent candidates to plug the gaps in the subordinate ranks. The spectre of unemployment, or the offer of slightly better pay than could be obtained for equivalent jobs in Ceylon, often convinced young Burghers to board a steamer in Colombo and take up residence in British Malaya.

Another common avenue to land a comfortable clerkship was sport, particularly cricket. The Dutch Burghers of Ceylon had long excelled in this increasingly popular game. Talented batters and bowlers, who distinguished themselves during the frequent inter-colonial tournaments that pitted Ceylonese, Indian and Malayan teams against one another, could hope to be scouted by the opposing squad and offered a clerical job in Malaya.

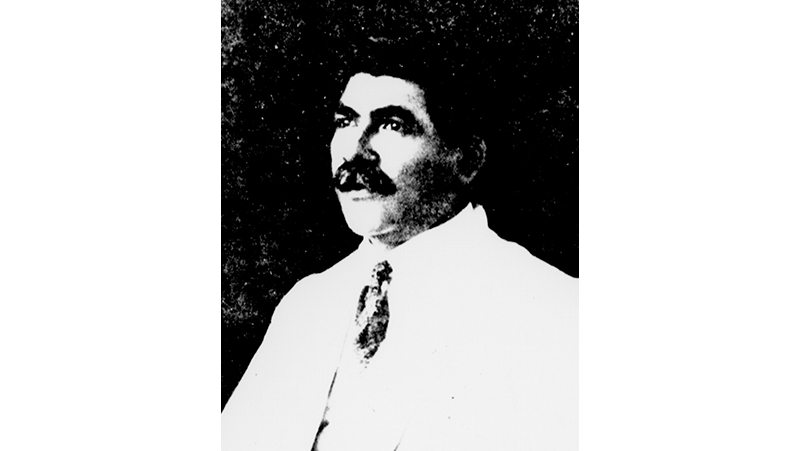

Edward Arnold Christoffelsz, for example, scored the highest batting average for Ceylon in a match-up with Selangor in 1891 and was promptly recruited by the state’s government.13 Another Burgher, Allan Jumeaux, freshly graduated from St Thomas College in Colombo, had similarly distinguished himself on the pitch and joined Penang’s Survey Department in 1889. But when Jumeaux was fielded for the Penang team in a match against Perak, he attracted the attention of the British Resident Ernest Woodford Birch, who personally offered him an appointment in Perak that came with nearly double the salary.14

Young Burghers were well aware that “a capable cricketer could always be sure of gaining employment out here with average intelligence”, and the Morning Tribune concluded in 1938 that Burghers had “made a valuable contribution to the rapid progress of cricket” in British Malaya.15

However, this sport-centred recruitment policy had its detractors and became a topic of debate in the Straits Times following the scandal that led to the arrest of Christoffelsz in 1894. He excelled on the pitch but turned out to be a dishonest employee who embezzled government funds to holiday in Japan. The brazen young man was promptly arrested while travelling from Japan to Ceylon and sentenced to three years of rigorous imprisonment in the Singapore jail.16

Letters published in the newspapers questioned the need to recruit clerks from Ceylon in view of the availability of local labour, and some alleged that the Christoffelsz case was representative of the state of the Selangor government.17 One commentator even suggested that the government had become a “bloated bureaucracy of lazy pleasure-seekers” that “created lucrative sinecures for minions who minister to the idle vanity of athletics by deputy”.18

The Christoffelsz case was, however, an isolated one and hardly representative of the trajectory of Burghers who joined the ranks of government in British Malaya on account of their sporting abilities. Allan Jumeaux, for example, steadily advanced through the ranks of the Perak Public Works Department and was awarded, upon his retirement in 1929, the Imperial Service Medal in acknowledgement of his distinguished career.19

Many of these young Burgher pioneers bore old Dutch surnames such as Van Cuylenburg, Koelmeyer, Ferdinands, Felsinger and Christoffelsz, which were reminiscent of the days when Ceylon was a colony governed by the Dutch East India Company. But there were also young men with a Burgher background whose names were distinctly French (Jumeaux for instance) or Portuguese, such as Pat Zilwa, who transferred from Colombo to Selangor to take up a bank clerkship in Kuala Lumpur.

In the course of a long and meritorious career, Zilwa distinguished himself as an exemplary public servant and was the first Ceylonese Burgher in Malaya to be made a Justice of Peace in 1926 and the recipient of the Malayan Certificate of Honour upon his retirement in 1935. Zilwa also left his mark on Selangor society and was an indefatigable organiser involved in various associations and charities, acting as president of the Selangor Recreation Club, vice-president of the Selangor Boy Scouts, honorary steward of the Selangor Turf Club and treasurer of the Selangor Football Association. He was also one of the founders of the Kuala Lumpur Rotary Club and the driving force behind the Imperial Indian War Relief Fund, which collected donations to alleviate the suffering of the thousands of Indian soldiers who had been maimed for life fighting under the banner of the Union Jack during the First World War.20

Lure of the Homeland

Pat Zilwa exemplified the trajectory of Ceylonese Burghers who fully integrated into Malayan society and never looked back. But there were also young men who continued to feel the pull of their homeland and wished to visit family or find a suitable marriage partner in the Burgher community. This presented a problem because subordinate government clerks were only entitled to two weeks of annual leave, which practically prevented Ceylonese and Indian employees from making the journey by steamship that alone would take a fortnight.

In the early 1890s, a group of Burgher residents in Malaya petitioned the government for more flexible leave privileges. They requested the right to accumulate their leave and be allowed to take a longer sabbatical.21 They also made the case for a more generous exchange compensation rate for Eurasian officers on paid leave who, under prevailing conditions, saw much of their hard-earned salary evaporate when it was converted into Ceylonese rupees. At the time, the exchange compensation was only granted to European officers.22

Various Burgher commentators supported the petition in articles published in the leading newspapers of the day. In the British imperial edifice, rank, race and privileges were neatly interwoven, and the Burgher voices that appeared in print sought to justify their reasonable plea for more flexible leave conditions by resorting to racial arguments. They presented the Burghers as a respectable community of Dutch descent which, historically had been on a par with Europeans, and was naturally superior to other Ceylonese or Malayan Eurasians. This unique status, or so the argument went, should entitle them to more generous conditions of leave. In those days, European officers received three months of full pay and 12 months of half-pay leave after serving six years. Thus, as a letter to the Straits Times suggested, Burghers should be entitled to two months of full pay and six months of half-pay leave after six years of service, while Tamils and Sinhalese would deserve one and three months respectively under a similar arrangement.23

Somewhat predicably, this did not go down well with Tamil and Sinhalese clerks recruited from Ceylon. Tamil and Sinhalese commentators joined the fray and the editors of the Straits Times were deluged with an incessant stream of letters. These, in no uncertain terms, dismissed the Burgher claim to special treatment. Instead, they resorted, in turn, to worn stereotypes and racial slurs which contrasted the right of the “pure sons” of the Ceylonese soil to visit their native land, with the pretensions of a hybrid, nondescript race that had sprung from the loins of European conquistadores and, it was hinted, far from respectable mothers.24

Before the editors shut down a debate that showed irreconcilable positions and worrying signs of escalating into a fruitless exchange of highly inflammatory rhetoric, one Burgher commentator hit back, stating that “our positions, ideas of civilisation, and social status are above theirs” and “we do not desire to be considered as being on a par with them” (referring to the Tamils and Sinhalese).25

A bemused European observer expressed sympathy with “the domestic affections” of the Burgher civil servants but could not resist adding that they were after all Eurasians, who have “neither the Englishman’s capacity for endurance nor the philosophic indifference of the Asiatic”.26

As these letters reveal, the Burgher petitioners did themselves a disservice by resorting to tropes of racial exceptionalism and class snobbery. Instead of finding common ground and petitioning the government on behalf of all Ceylonese employees, the Burghers had kicked a hornet’s nest and found themselves suddenly on the defensive. Not only did other Ceylonese communities challenge and resent the Burghers’ claims to special treatment and privileges, the leave controversy also begged the question to what extent the Burghers belonged to Malaya’s Eurasian community.

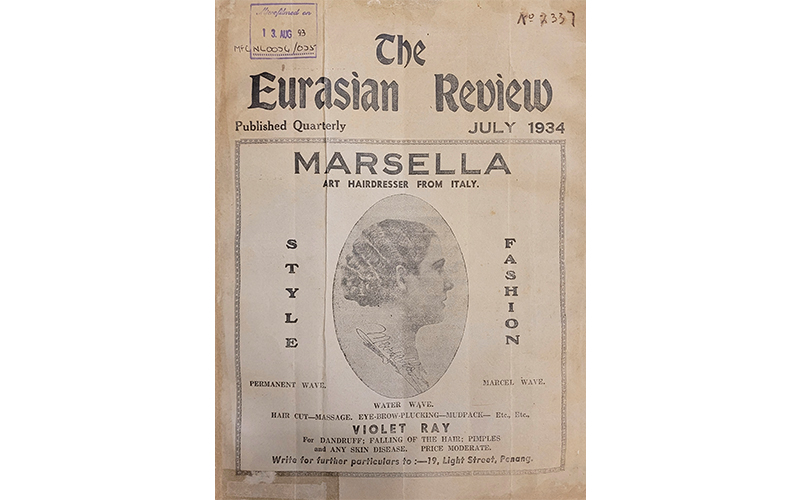

What’s in a Name: Eurasian or Burgher?

In the first decades of the 20th century, the Eurasians increasingly felt the need to form an organisation to advance their interests and unite the community. Following various initiatives, the Eurasian Association was founded in 1919 with the aim to bolster social cohesion and promote the interests of all Eurasian subjects in British Malaya. Its main branches were located in Singapore, Penang, Selangor and Negeri Sembilan, but the association had from the get-go a transimperial orientation and vowed to “afford to Eurasian British subjects, who may require it, the assistance of the Association in any other country”.27

However, as T.C. Archer, a leading figure within the Eurasian community, pointed out in a letter published in the Straits Times, the Dutch Burghers had been “conspicuous by their absence” from the meeting preceding the foundation of the association and had flatly refused to be associated with the movement. Archer was genuinely puzzled by this snub, especially since the Burghers had, as he observed, also “their streak of Asiatic blood” and, moreover, shared a similar predicament because the government did not make a distinction between Malayan Eurasians or other mixed-race communities of European descent, including Burghers or Anglo-Indians domiciled in British Malaya.28

Archer’s appeal for unity was promptly answered by a flurry of letters signed by Dutch Burghers, who made it clear that they were in sympathy with the movement but took issue with the label “Eurasian”.29 The Burgher community had long occupied a respectable and privileged position in Ceylonese society. Following the transition from Dutch to British power, the Dutch Burghers evolved into a highly educated minority group that wielded substantial power and supplied the colony with some of its leading civil servants, lawyers, judges and educators.

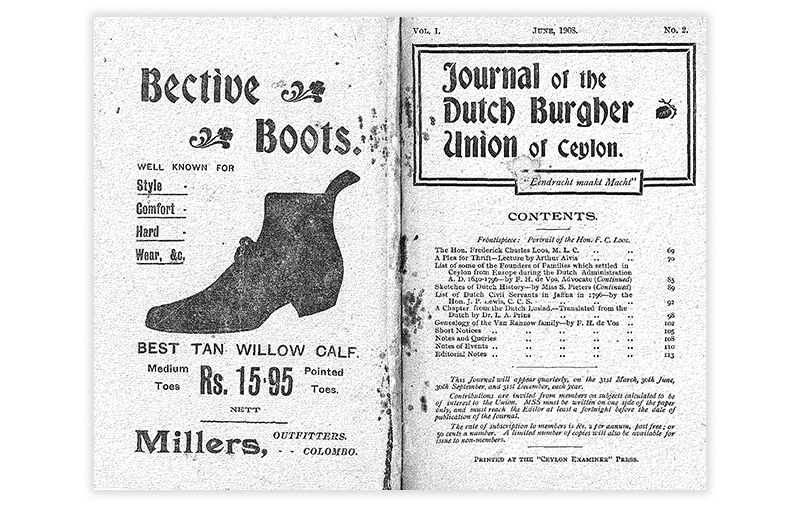

Dutch patrilineal lineage was a key criterion for defining whether one was Burgher, and although the reality was much more muddled, the Dutch Burgher Union of Ceylon, founded as early as 1908, actively sought to distinguish the community from the poorer and less privileged classes of Portuguese Eurasians and Anglo-Ceylonese.

This Dutch lineage claim thus became a badge of pride, but also functioned as a subtle class marker in Ceylon. While the leaders of the Eurasian community in British Malaya were taken aback by Burgher claims of exceptionalism, the Dutch Burghers, in turn, were horrified to be labelled “Eurasian”, even if the question of nomenclature notwithstanding, they had everything to gain from a strong, unified front to advance common interests and fight the discrimination that mixed-race communities of European descent faced across the colonial world.

The question of the status of Dutch Burghers within the Eurasian community of British Malaya remained an open one. Since there was no Malayan equivalent of the Dutch Burgher Union, it was very much up to each individual how they navigated the subtle racial hierarchies that divided colonial society. However, in contrast to the majority of the Tamil and Sinhalese civil servants who moved back to Ceylon upon retirement, most Dutch Burghers opted to stay and married locally. Their descendants became domiciled Malayans who identified with the new nation-states that emerged from the ruins of Empire.

Today, the migration history of the Dutch Burghers is largely forgotten and only the intergenerational transmission of customs, recipes for Ceylonese delicacies, or the distinct Dutch ring of a surname serves as a reminder of the young pioneers who left their island-home to start a new life in British Malaya.

Dr Yorim Spoelder is a historian affiliated with the Freie Universität Berlin and a former recipient of the Lee Kong Chian Research Fellowship (2024). He is the author of Visions of Greater India: Transimperial Knowledge and Anti-Colonial Nationalism, c. 1800–1960 (winner of the 2024 EuroSEAS Humanities Book Prize). He is currently working on a transimperial and comparative history of the identity and politics of Eurasian communities in British India, Ceylon, the Straits Settlements and the Dutch East Indies.

Dr Yorim Spoelder is a historian affiliated with the Freie Universität Berlin and a former recipient of the Lee Kong Chian Research Fellowship (2024). He is the author of Visions of Greater India: Transimperial Knowledge and Anti-Colonial Nationalism, c. 1800–1960 (winner of the 2024 EuroSEAS Humanities Book Prize). He is currently working on a transimperial and comparative history of the identity and politics of Eurasian communities in British India, Ceylon, the Straits Settlements and the Dutch East Indies. Notes

-

“Double Tragedy in Johore,” Straits Times, 13 July 1932, 12; “Death Sentence in Johore Trial,” Straits Times, 2 August 1932, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Murder in Johore: Man and Woman Found Stabbed,” Straits Times, 27 June 1932, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“I am Going to Kill My Father,” Straits Budget, 21 July 1932, 14. (From NewspaperSG); “Death Sentence in Johore Trial.” ↩

-

“Double Tragedy in Johore”; “Death Sentence in Johore Trial.” ↩

-

“Death Sentence in Johore Trial”; “I am Going to Kill My Father.” ↩

-

“Double Tragedy in Johore”; “Death Sentence in Johore Trial.” ↩

-

“Murderer Hanged,” Straits Times, 28 October 1932, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Ceylon Cricketers for the Straits,” Straits Budget, 14 September 1901, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Ceylon Pioneer in Malaya,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 28 February 1940, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Ceylon Pioneer in Malaya”; “Ceylon Burghers Raise All-Malayan Cricket XI,” Morning Tribune, 19 March 1938, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Assizes,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 12 September 1894, 3; “The Encouragement of Cricket,” Straits Budget, 18 September 1894, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Scrutator, “The ‘Straits Times’ on Cricket and Eurasians,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 11 October 1894, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Pat Zilwa, “Imperial Indian War Relief Fund,” Straits Times, 28 June 1917, 8; “First Burgher J.P.,” Straits Budget, 9 September 1926, 15; “Eurasians in Selangor”, Straits Times, 10 July 1932, 13; “Farewell Party: Retirement of Mr. Pat Zilwa,” Malaya Tribune, 26 June 1935, 9; “Fine Record of Service,” Straits Times, 2 July 1935, 5; “KL Loses Colourful Social Worker,” Sunday Standard, 10 January 1954, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Ceylonese in Straits,” Straits Times, 2 July 1892, 5; “The Ceylonese Clerks of Malaya,” Straits Times, 23 July 1892, 2; “One of Them”, “Exchange Compensation,” Straits Budget, 18 June 1895, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Memorial of the Eurasians in Government Service,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 5 June 1894, 3; “The Eurasian Civil Servants,” Straits Budget, 5 June 1894, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

A Burgher, “The Leave Question,” Straits Times, 26 August 1895, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

A Singhalese, “Untitled,” Straits Times, 2 September 1895, 3; A Singhalese, “The Leave Question,” Straits Budget, 3 September 1895, 14; A Tamil, “The Leave Question,” Straits Budget, 10 September 1895, 13; Ceylon Tamil, “The Leave Question,” Straits Times, 12 September 1895, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

A Burgher, “The Leave Question,” Straits Budget, 17 September 1895, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Ceylonese Clerks of Malaya,” Straits Times, 23 July 1892, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“A Sign of Progress,” Straits Times, 9 June 1919, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

T.C. Archer, “Eurasian Unity,” Straits Times, 14 June 1919, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Hollandsche Burgher, “Eurasian Unity,” Straits Times, 17 June 1919, 8; R.V. Chapman, “Eurasian Unity,” Straits Times, 28 June 1919, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩