From Liguria to the Lion City: The Life and Times of Giovanni Gaggino

The remarkable story of an Italian merchant who once owned Pulau Bukom and authored an Italian-Malay dictionary in colonial Singapore.

By Alex Foo

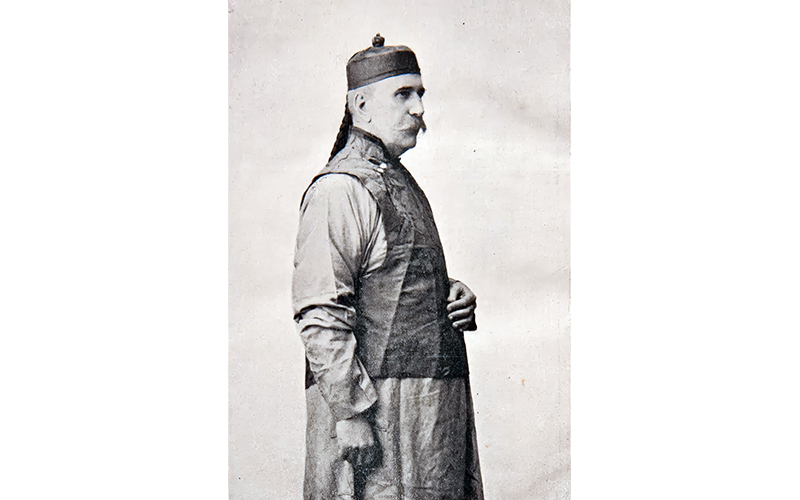

Long before the era of container ships and globalised trade, before the First World War and even before the full unification of Italy in 1871, an Italian mariner stepped off his boat onto the shores of Singapore, armed with little more than his wits and a sailor’s instinct for opportunity. He had neither connections nor a fortune. Yet, by the time he died in 1918 at the age of 72, Giovanni Gaggino had transformed himself into a millionaire merchant, shipowner and author.

Born in 1846 in the town of Varazze, in the northwestern coastal region of Liguria, Gaggino made Singapore his home for over four decades, launching a flurry of ventures that ranged from the purchase of Pulau Bukom to a rubber plantation in Thailand. He built a thriving ship chandlery, Gaggino & Co., capitalising on the port’s explosive growth to supply ships with sundry maritime necessities. He also sailed up the Yangtze River in China, ventured into Vladivostok in Russia and trekked throughout Southeast Asia in search of business opportunities. While Gaggino may not have been the first Italian to pass through Singapore, he was arguably the first to leave his mark.

The Italian Presence in the Straits

Unlike the Portuguese, British and Dutch, whose colonial ambitions led them to wage battles and establish dominions across Southeast Asia, the Italian presence in the region was more modest. However, Italian merchants and missionaries had long sailed through the Strait of Singapore.1

In the 1510s, the Florentine merchant Giovanni da Empoli, who accompanied the Portuguese viceroy Afonso de Albuquerque on his conquest of Melaka, recorded his last will and testament onboard a ship anchored in Singapore.2 In 1599, another Florentine, Francesco Carletti, described the Old Strait of Singapore as “so narrow a channel that from the ship you could jump ashore or touch the branches of the trees on either side”. A century later, in 1695, the Neapolitan traveller Francesco Gemelli Careri sailed through the same strait. He recorded the sight of islets dotting the waterway and 10 thatched houses perched on stilts in his travelogue, Voyage Around the World.3

Gaggino’s first encounter with Singapore was in 1866.4 He came from a seafaring family: his father and five brothers were all sailors who made their living at sea, trading with the Far East. The subsequent death of his father left his family in dire financial straits, which propelled Gaggino to set sail for cosmopolitan Singapore where he hoped to work as an interpreter. He was a polyglot who spoke Italian, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Malay and English. He learned the latter when his father, in what proved to be a prescient move, sent him to England at the age of 14.5

When Gaggino arrived in Singapore sometime around 1874 on the ship Fratelli Gaggino, the Italian population was small. Between 1883 and 1897, there were only around 290 Italians, 56 of whom had come directly from Italy while others rebounded from other regions in the east.6 The Italian population would remain small until the end of Gaggino’s life in 1918.

Tycoon of the Tropics

There is a Latin saying, Genuensis ergo mercator, which means “Genoese, therefore a merchant”.7 Although Gaggino was not strictly from Genoa, hailing instead from the neighbouring province of Savona, the adage nonetheless applied.

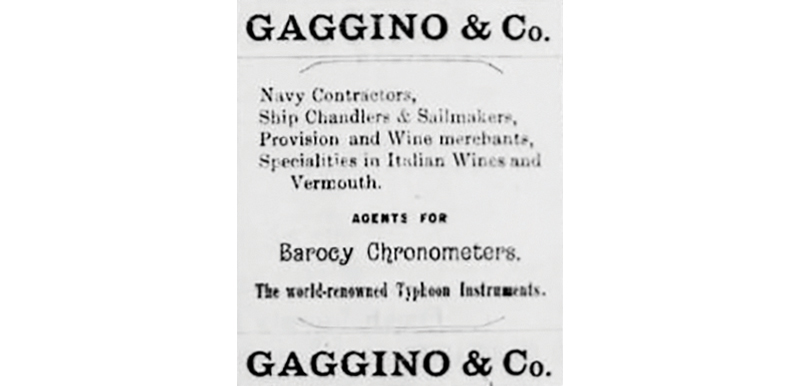

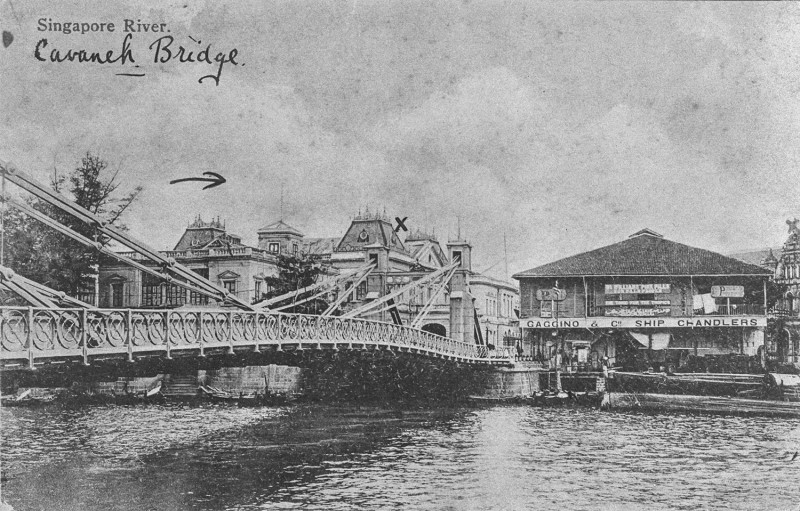

By 1876, he had founded Gaggino & Co., a ship chandlery that provided supplies and equipment to vessels passing through Singapore. The business quickly grew into a trusted name. Chandlers were judged by their speed and reliability, and Gaggino promised “water and coal supplied at the shortest notice”, minimising downtime for ships and maximising efficiency. His office stood near Cavenagh Bridge, just across the road from the General Post Office (where Fullerton Hotel now stands) until 1914.

Gaggino & Co. was located near Cavenagh Bridge, just across the road from the General Post Office (now the Fullerton Hotel), 1900s. This image is reproduced from a postcard published by Kong Hing Chiong & Co. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore (Media - Image no. 19980005492 - 0021).

Gaggino & Co. was located near Cavenagh Bridge, just across the road from the General Post Office (now the Fullerton Hotel), 1900s. This image is reproduced from a postcard published by Kong Hing Chiong & Co. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore (Media - Image no. 19980005492 - 0021).The company was eventually appointed to the Russian, French, German, Austrian, Spanish, Portuguese and Italian navies.8 Gaggino’s business venture, however, did not stop here. Interestingly, he was once the owner of Pulau Bukom.

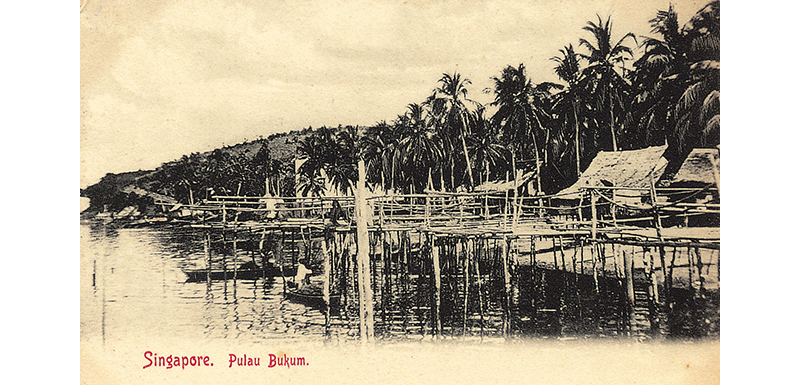

A small island about 5 km south of the Singapore mainland, he had purchased it for a mere $500 when it was known as Freshwater Island.9 The island got its name because of the freshwater well on it. This well allowed Gaggino to supply passing ships with drinking water.

In 1891, M. Samuel & Co. of London, an early player that would later become Shell, sought to build a petroleum tank depot on mainland Singapore at Bukit Chermin and Pasir Panjang. The idea was met with fierce opposition. Merchants feared the danger of flammable cargo so close to the city, so much so that the press labelled it a “petroleum plot”.10

The government swiftly rejected the plan.11 The company thus set their sights on Pulau Bukom. The island had a sheltered harbour, a deep sea waterfront and, crucially, was beyond harbour limits, so no government inspections of steamships were required.12 The company put it plainly: “As nearly all oil sold here has to be transshipped, [we] might as well ship [them] from Freshwater Island as from Singapore.”13 The company, through merchant and agency house Syme & Co., acquired 8 ha of the island from Gaggino in 1891, earning him a tidy sum of $3,000.

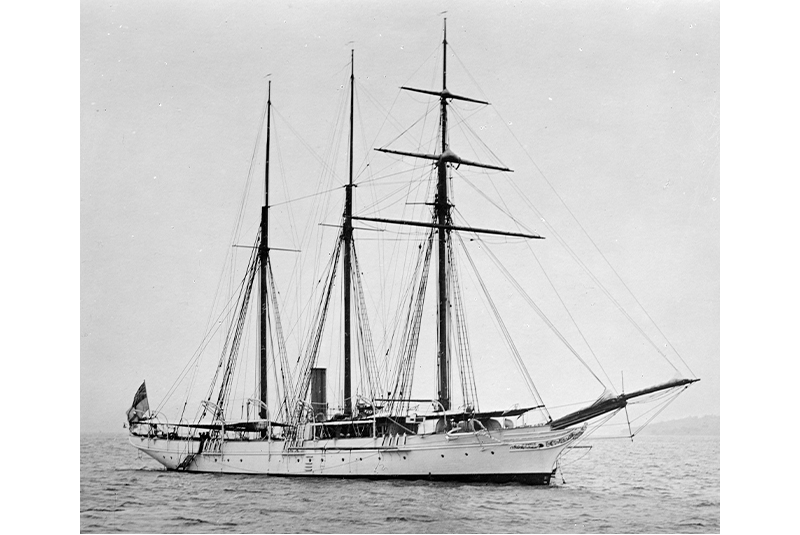

Gaggino subsequently invested some of his profits in ships. A report in the Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser described how he acquired the Dutch steamer Srie Banjar in January 1899. He reflagged the vessel under Italian registry and renamed it Libertas. A baptism was held at the harbour, presided by Father Charles Bénédict Nain, vicar of the Cathedral of the Good Shepherd. Father Nain would also christen Gaggino’s two other ships: the Santa Anna and Santa Tarcila. A sunken British surveying vessel, the HMS Waterwitch, also joined his collection in 1912. Gaggino had it refloated and then refitted as his private yacht, the Fata Morgana.14

Apart from running Gaggino & Co., Gaggino was also managing director of Soon Keck Line of Steamers, Limited. During the First World War, he convened an extraordinary general meeting to donate $6,150 to the Straits Settlements War Loan to support the British and the Allies against the Germans. He was, as noted by the papers, disappointed by the lukewarm response of local companies as he felt that it was British naval prowess that had made their wealth possible.15

Gaggino also looked towards the wider region, diversifying into rubber and tin. He bought 16,000 rais (approximately 256 ha) of land in 1910 for the development of rubber plantations in Trang, Thailand. In 1913, he founded Mutual Trading Limited with a capital of $200,000 to develop the shipping trade with neighbouring colonies.16

Gaggino’s Italian-Malay Dictionary

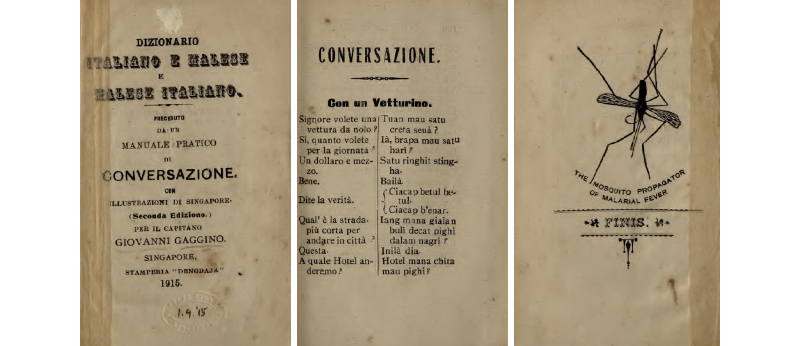

In 1884, Gaggino published the Dizionario Italiano e Malese: Preceduto da un Manuale Pratico di Conversazione per Servire d’Interprete al Viaggiatore che Vista e Traffica con la Malesia (Italian-Malay Dictionary: Preceded by a Practical Conversational Manual to Serve as an Interpreter for the Traveller Visiting and Trading with Malaya) through Denodaya Press in Singapore. It was a 388-page publication containing a handbook of phrases for everyday conversations as well as a dictionary of Italian words in alphabetical order and their corresponding Malay equivalents in both romanised and Jawi scripts.17

This remarkable undertaking was dedicated to Sultan Abu Bakar, the so-called Father of Modern Johor, a reformist monarch whose modernisation drive gained him seven foreign decorations including, Gaggino was careful to note in the preface, the Commander of the Order of the Crown of Italy.18

We have no proof that Gaggino and the Anglophile sultan ever met, but the gesture was typical of the Italian merchant. He was always attuned to the possibility of trade and mutual interest. In his humble and self-effacing dedication, he described the book as a “tiny grain (granellino) in the polyglotism of the century” inspired by the “ever-growing commerce between Italy and Malaya”.19 The sentiment was modest, but not unserious. Language, for the multilingual Gaggino, was a lubricant for commerce. He hoped that his compatriots would use his book and learn “to make himself understood and to understand others in the Malay language”.20

In 1915, 31 years after the publication of the first edition which had long gone out of print, Gaggino published a new expanded edition, also through Denodaya: the Dizionario Italiano e Malese e Malese Italiano (Italian-Malay and Malay-Italian Dictionary). The new edition was now bidirectional and included descriptions of notable Singapore landmarks such as Cavenagh Bridge, the Singapore River and Raffles Square. Gaggino noted in the updated preface that “a large number of Malays and Javanese can now read and write using Roman characters”. He further observed that parents were sending their children to school at an earlier age and that while Malay was taught using Jawi script, the “Roman script is becoming more common as it is simpler to learn”.21 His hope, with the expanded edition, was that people-to-people contact between Italy and Malaya would grow.

Gaggino had no illusions about the academic rigour of his endeavour. It would not, he admitted in both editions, “meet the needs of a scholar or, even less, a philologist”. Nonetheless, it was a practical project. The Malay language was widely used in the region, spoken not just in Singapore but also in “Sumatra, Java, the Malay Peninsula, the surrounding regions, Cochin China, Siam, the Dutch East Indies, and as far as New Guinea”. He found the language not only useful but beautiful. The Malay of Pahang, he wrote, was especially dulcet and “highly suitable for singing”.22

Organised by semantic fields, the Dizionario transcribed Malay words in the Italian orthographic system for the ease of Italian travellers.23 For instance, the Malay word for “far” (jauh) is given as giau, which Italians would have pronounced with a soft “j”.24 The dictionary begins with basic grammatical categories such as pronouns, prepositions and conjunctions. Thereafter, there are sections on body parts, animals, clothing and occupations, among others.25 For the seasons, Gaggino noted that instead of the usual four, the Malays only know two: the northeast and southwest monsoon periods.26

The longest section, comprising 77 entries, is devoted to maritime vocabulary, covering terminology such as hatch and bowline. Elsewhere, Gaggino offered practical dialogue scenarios. These include phrases on how to find a hotel, speak to a coachman, order at a market and comment on the weather. The Dizionario also contains an alphabetical section of frequently used terms – some of them less than polite, though certainly of utility. There is “shut up” (zitto/diam) and “screw him” (fregatelo/sapù, gosò).

The Malay in Gaggino’s dictionary was colloquial Malay. The question “Boy, where is your master?” is rendered as “Boi, dimana ada lu punia tuan?27 Comprising a mix of colonial and local tongues, the phrase uses boi (a Malay loanword from English for “servant”) and lu (a Hokkien-derived pronoun for “you” and used to address subordinates).28 An Italian scholar identifies N.B. Dennys’ A Handbook of Malay Colloquial, As Spoken in Singapore (1878) as one of Gaggino’s sources.29

Gaggino’s annotated copy of Dennys’ handbook now resides at the Civic Library of Pontinvrea in Italy.30 However, Gaggino did not simply reproduce from Dennys’ handbook. For example, Gaggino used the English-derived pensel for “pencil” instead of Dennys’ kalam timah. Gaggino also made some errors. The word for “crow” is given as the word for “elephant”, and the Italian for scarlet (scarlatto) is translated as “ugu” which could have been a misrendering of ungu which actually means “purple”.

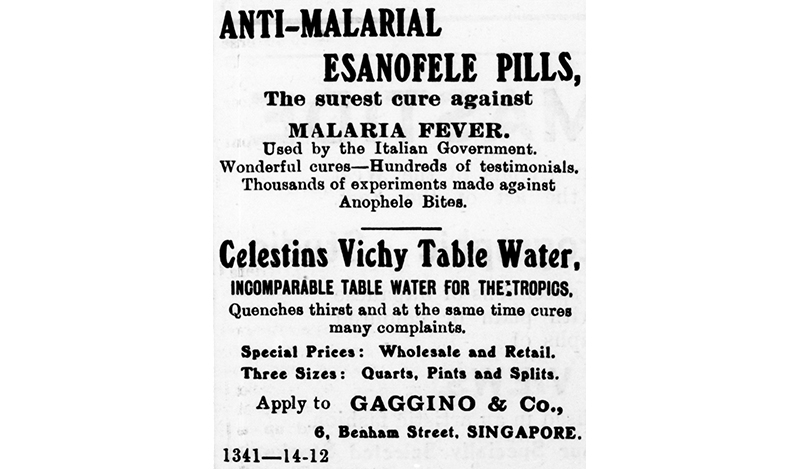

One notable difference in the second edition of the Dizionario is the preponderance of advertisements for Gaggino’s company within. Scattered throughout the book are five advertisements in English, Danish and French. Even within an introductory description of Raffles Square, Gaggino inserted a mention of his company’s office and not so subtly hawked his company’s wares, advertising its stock of French Vittel water, known for its curative properties, and a special type of malaria medicine. He was, after all, an inveterate merchant.

It is difficult to ascertain the reception of the second edition. The publication of two different editions, along with the presence of copies in several libraries across Italy, points to a modest but noteworthy degree of distribution. That said, by the turn of the 20th century, English had become and would remain the lingua franca of commerce in Singapore and Malaya.

Gaggino and His Motherland

In the prefaces of both editions, Gaggino described himself as a proud Italian who had “never forgotten to promote the well-intended interests of his motherland in these distant countries”. Gaggino declared in the second edition: “We must emigrate if we wish to become independent and wealthy.” He added: “We need people with some commercial training, who know English at least”, as Italian labourers could not compete with local inhabitants who were industrious and inexpensive.31

Gaggino was also concerned about Italy’s reliance on second-hand trade through colonial intermediaries and its commercial lag compared to other European powers. To circumvent these issues, he felt that an Italian trading presence was needed on the banks of the Yangtze in China. In 1898, Gaggino sailed up the famed river and stopped at various ports. He found English, French, German, Austrian and Belgian goods but “no matter how hard [he] searched everywhere, [he] found nothing of Italian origin”.32 Only in Yichang, Hubei province, did he come across a solitary bottle of Cinzano vermouth which he promptly purchased for five lire.33

The captain cast a critical eye on his country’s inwardness, lack of initiative and petty bureaucracy. Lamenting that Italy did not know how to use credit to trade, he raised Switzerland as an example: “There are states that have no navy, yet they travel the world more than we do. Look, for example, at Switzerland and other nations that know how to lose in order to gain.”34

Gaggino, too, condemned the “ferocious cretinism” of Ligurian customs, recounting an incident where an Italian municipal customs officer thoroughly searched and patted him down, and having found nothing to tax for their benefit, fined him for failing to declare a package of Lumière gelatin silver-bromide plates.35

Gaggino’s Legacy (or Lack Thereof) in Singapore

Gaggino died at the age of 72 in February 1918 while on holiday in Java. At the point of his death, he had built a sprawling commercial empire spanning Singapore and mainland Southeast Asia. His estate was valued at approximately $2.5 million, owing to his success in rubber, tin mining and maritime trade. The Straits Times described him as a “keen businessman” and “well-liked by all who knew him”.36

Having never married, Gaggino left detailed instructions in his will dated July 1917. While he provided inheritances for a nephew and niece in Singapore, he explicitly excluded other relatives due to what he called their “execrable conduct”.37 He instructed that all holdings of Gaggino & Co. be liquidated. Goods from his stores on Sambau Street and Malacca Street were sold off at an auction.38 His real estate holdings, too, were put up for sale, including two 999-year leasehold seaside bungalows in Tanjong Rhu fetchingly named Villa Alba and Villa Tramonto (Dawn and Dusk respectively), and a shophouse at 131 Middle Road.39

Gaggino sought to create a cultural and philanthropic legacy for his hometown of Varazze. To the town, he bequeathed a trove of coins, furniture, bronzes, porcelain, trinkets, antiquities and books – all collected during his long stay in the East – 30 cases of which sat in Singapore, awaiting shipment.40

To display his collection, he allocated 50,000 lire to purchase a building for a museum to be named in his honour in Varazze. He also left directions in his will for his brother Paolo to build a hydrotherapy facility to harness a local spring’s reputed medicinal waters. To support these efforts, Gaggino established a charity fund that would be managed by the municipality and upkept by his remaining assets.41 This was to be his legacy: to bring parts of Asia to Europe and to bring prosperity to his people.

However, it was not to be. Legal disputes broke out in the Italian courts. The municipality of Varazze, fearful of litigation from disinherited relatives and unsettled by an initial unfavourable ruling, chose to settle. In doing so, they relinquished their rights to the estate in favour of Gaggino’s brother Federico.42 Neither the museum nor the charity fund materialised.

In 1922, empowered by the Italian court, Gaggino’s nephew Cesare Gaggino opened a probate suit in Singapore and was granted administrative control of his uncle’s remaining assets, then estimated at $400,000. Before returning to Genoa, he honoured his uncle’s charitable commitments: $1,550 each to the Pauper Hospital and the General Hospital, $1,250 each to the French Convent and the Portuguese Convent, and $200 to the Masonic Lodge Zetland.43

Some parts of Giovanni Gaggino’s wide-ranging collection survive today. The Civic Library of Pontinvrea and the Genoese Museums house several objects. Five ancient Malayan adzes – cutting tools with arched blades – found their way to Vienna’s Weltmuseum Wien, a gift from Gaggino to the Austro-Hungarian naval commander Constantin Edler von Pott. Gaggino had called these adzes “the oldest monuments of the peninsula”, dating to the Neolithic period and unearthed in 1894 during mineral excavations in Perak, Malaya.44

Gaggino’s life was one of motion and reinvention – part autodidact, part entrepreneur, entirely self-made. As Singapore and Italy mark 60 years of diplomatic relations in 2025, it is worth remembering that Giovanni Gaggino was not just a merchant or adventurer, but also a self-appointed envoy of goodwill to his “beloved country” (amato paese), Singapore.45 He was a pioneer who sought to build a bridge between his homeland and his adopted port – one word, one deal and one dictionary at a time.

This article is dedicated to my father, no stranger to the seas.

Alex Foo is a Manager in the Partnership Department at the National Library Board. Formerly a literary arts librarian, he has written for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Orientations and ArtsEquator.

Alex Foo is a Manager in the Partnership Department at the National Library Board. Formerly a literary arts librarian, he has written for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Orientations and ArtsEquator.Notes

-

Derek Heng, “Continuities and Changes: Singapore as a Port-City over 700 Years,” BiblioAsia 1, no. 1 (2005): 12–16. ↩

-

Kwa Chong Guan et al. eds., Seven Hundred Years: A History of Singapore (Singapore: National Library Board and Marshall Cavendish International, 2019), 81. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 KWA-[HIS]); Matteo Salonia, “A Dissenting Voice: The Clash of Trade and Warfare in Giovanni da Empoli’s Account of His Second Voyage to Portuguese Asia,” Itinerario 45, no. 2 (2021): 189–207, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0165115321000176. ↩

-

Kwa et al., Seven Hundred Years, 103, 158–59. ↩

-

Francesco Surdich, “Da Varazze a Singapore: Giovanni Gaggino (1846–1913),” Atti e Memorie della Società Savonese di Storia Patria 26 (1990): 150, https://www.storiapatriasavona.it/archivio-pubblicazioni/atti-e-memorie-n-s-1967-2012/. ↩

-

In 1872, Giovanni Gaggino also circumnavigated the globe and commanded the first Italian ship to arrive in New Zealand. Luigi Santa Maria, “Giovanni Gaggino e Il Suo ‘Dizionario Italiano e Malese’,” Asia no. 5 (1995): 8, http://www.cesmeo.it/public/pdf/L.%20Santa%20Maria,%20Giovanni%20Gaggino%20e%20il%20suo%20Dizionario%20italiano%20e%20malese%20pt.%201.pdf. ↩

-

Maria Clotilde Giuliani-Balestrino, “L’Italia Fuori dall’Italia. Gli Italiani a Singapore: Dai Primi Viaggiatori Agli Imprenditori Odierni” [Italy outside of Italy. Italians in Singapore from the first travellers to today’s entrepreneurs], Studi e Ricerche di Geografia 24, no. 2 (2001): 128, https://studiericerche.org/rivista/annata-24-2001/. ↩

-

This phrase reflects the historical reputation of Genoa as a city of traders and merchants during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. The Genoese were known for their extensive trade networks, spanning the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. ↩

-

Giovanni Gaggino, Dizionario Italiano e Malese e Malese Italiano [Italian-Malay and Malay-Italian Dictionary] (Singapore: Stamperia Denodaya, 1915), 69. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

“Death of Captain Gaggino,” Straits Times, 14 February 1918, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Yeo Ai Hoon, Enterprise in Oil: The History of Shell in Singapore, 1891–1960, manuscript (n.p.: n.p., 1988). 8. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 338.27282095957 YEO) ↩

-

Walter Makepeace, Gilbert E. Brooke, Roland St. J. Braddell, eds., One Hundred Years of Singapore, vol. 2 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1991), 97. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 ONE); The Founding Years 1891–1991 (Kuala Lumpur: Shell Malaysia Ltd, 1991), 30–31. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 338.272809595) ↩

-

Nicky Moey, The Shell Endeavour: First 100 Years in Singapore (Singapore: Times Editions Pte Ltd, 1991), 27. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 338.2728 MOE). ↩

-

Yeo, Enterprise in Oil, 11. ↩

-

“Untitled,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 12 January 1899, 10; “Death of Capt Gaggino,” Singapore Free Press, 14 February 1918, 99; “Shipping Notes,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 12 November 1912, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Soon Keck Ltd. Generous Contributions to War Funds,” Malaya Tribune, 3 March 1917, 4; “Soon Keck Line of Steamers, Limited,” Straits Times, 16 February 1918, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Rubber & Coconuts in Trang,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 7 October 1911, 4; “Untitled,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 5 February 1913, 6. (From NewspaperSG); Surdich, “Da Varazze a Singapore,” 180–83. ↩

-

Giovanni Gaggino, Dizionario Italiano e Malese: Preceduto da un Manuale Pratico di Conversazione per Servire d’Interprete al Viaggiatore che Vista e Traffica con la Malesia [Italian-Malay Dictionary: Preceded by a Practical Conversational Manual to Serve as an Interpreter for the Traveller Visiting and Trading with Malaya] (Singapore: Denodaya, 1884), preface, Prometheus-Academic Collections, https://tufs.repo.nii.ac.jp/records/11300. This was not the first Italian-Malay dictionary; that distinction belongs to the Venetian chronicler Antonio Pigafetta, who compiled one during Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan’s circumnavigation of the globe. Pigafetta participated in the expedition, setting of from Spain in 1519, and served as Magellan’s assistant. ↩

-

Giovanni Gaggino indicated this erroneously as “Commander of the Cross of Italy (Commendatore della croce d’Italia)”. The year 1871 marked the first official contact between a Malay ruler and an official representative of the new Kingdom of Italy, Captain Carlo Alberto Racchia, who commanded the corvette Principessa Clotilde to the Far East in search of a territory suitable for a new Italian penal colony. See A. Candilio and L. Bressan, “Sultan Abu Bakar of Johore’s Visit to the Italian King and the Pope in 1885,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 73, no. 1 (2000): 44. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website). ↩

-

Gaggino uses the word granellino, a diminutive that underscores the modesty of his effort. Yet his choice also echoes the biblical Parable of the Mustard Seed (granello di senape in Italian), in which a tiny seed grows into a large tree. Gaggino, Dizionario Italiano e Malese: Preceduto da un Manuale Pratico di Conversazione, preface. ↩

-

Gaggino, Dizionario Italiano e Malese: Preceduto da un Manuale Pratico di Conversazione, 388. ↩

-

Gaggino, Dizionario Italiano e Malese e Malese Italiano, ii. ↩

-

Gaggino, Dizionario Italiano e Malese: Preceduto da un Manuale Pratico di Conversazione, 2; Gaggino, Dizionario Italiano e Malese e Malese Italiano, iv. ↩

-

Antonia Soriente, “Cross-Cultural Encounters of Italian Travellers in the Malay World: A Perspective on the Languages Spoken by the Local Populations,” Wacana, Journal of the Humanities of Indonesia 25, no. 2 (2024): 170–71, https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/wacana/vol25/iss2/2/. ↩

-

Linguists refer to this as the voiced postalveolar affricate, the same sound found in the word “beige”. ↩

-

In the food section, for instance, he outlines rice in its full lifecycle: padì when unharvested in the field, brass (or beras) once threshed and nasì after it is cooked. ↩

-

Gaggino, Dizionario Italiano e Malese: Preceduto da un Manuale Pratico di Conversazione, 89. ↩

-

Gaggino, Dizionario Italiano e Malese: Preceduto da un Manuale Pratico di Conversazione, 124. ↩

-

Soriente, “Cross-Cultural Encounters of Italian Travellers in the Malay World,” 173. ↩

-

N.B. Dennys, A Handbook of Malay Colloquial, As Spoken in Singapore: Being a Series of Introductory Lessons for Domestic and Business Purposes (London: Trübner & Co.; Singapore: Mission Press, 1878). (From National Library Online); Santa Maria, “Giovanni Gaggino e Il Suo ‘Dizionario Italiano e Malese’,” 20. ↩

-

Santa Maria, “Giovanni Gaggino e Il Suo ‘Dizionario Italiano e Malese’,” 20. ↩

-

Gaggino, Dizionario Italiano e Malese: Preceduto da un Manuale Pratico di Conversazione, 2; Gaggino, Dizionario Italiano e Malese e Malese Italiano, iii. ↩

-

Giovanni Gaggino, La Vallata del Yang-Tse-Kiang: Appunti e Ricordi [The Yangtze valley: Notes and memories] (Rome: Fratelli Bocca, 1901), 86, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/lavallatadelyan00mayngoog. ↩

-

Surdich, “Da Varazze a Singapore,” 158. ↩

-

Gaggino, La Vallata del Yang-Tse-Kiang, 165. ↩

-

Gaggino, La Vallata del Yang-Tse-Kiang, 65–66. ↩

-

“Death of Captain Gaggino,” Straits Times, 14 February 1918, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Italian Will Suit,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (Weekly), 30 March 1922, 202. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Auction Sale of Ship Chandler’s Store,” Malaya Tribune, 18 December 1918, 7; “Important Auction Sale of Valuable Shipchandlers’ Stores,” Malaya Tribune, 17 February 1919, 5. (From NewspaperSG). The proceeds from the sale were divided as follows: 20 percent each to his brother Enrico and his nephew Paul Consigliere, with “5 percent each to the French and Portuguese Convents, the European Hospital, and the Tan Tock Seng Hospital”. See “Italian Will Suit.” ↩

-

Gaggino’s shophouse on Middle Road would eventually be occupied by the popular Japanese fabric store Echigoya from 1937–1945. “Preliminary Notice. Estate of Giovanni Gaggino, Deceased,” Malaya Tribune, 14 July 1919, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Death of Captain Gaggino,” Straits Times, 14 February 1918, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Surdich, “Da Varazze a Singapore,” 154. ↩

-

Surdich, “Da Varazze a Singapore,” 153–54. ↩

-

“Untitled,” Singapore Free Press, 8 June 1922, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The Weltmuseum Wien has a letter from Giovanni Gaggino that describes this gift of adzes. ↩

-

Gaggino, Dizionario Italiano e Malese: Preceduto da un Manuale Pratico di Conversazione, preface. ↩