Women Photographers in Singapore and Malaya

In the male-dominated world of 1940s and 1950s photography, three women in Singapore and Malaya found different ways to participate in photography as a studio photographer, a photojournalist and a photography enthusiast.

By Zhuang Wubin

Women don’t know how to take photographs!” a customer once declared at a Singapore photo studio. Wun Chek Hoi, the apprentice at the receiving end, proved him wrong and went on to become an accomplished woman studio photographer – a rare feat in that era of Singapore.1

Wun, Si Jing and Chew Lan Ying2 were three women who picked up the camera during the 1940s and 1950s for different reasons. Through their lens, they captured everything – from intimate moments of courtship to historic peace talks – discovering both pleasures and challenges while pursuing their craft and passion.

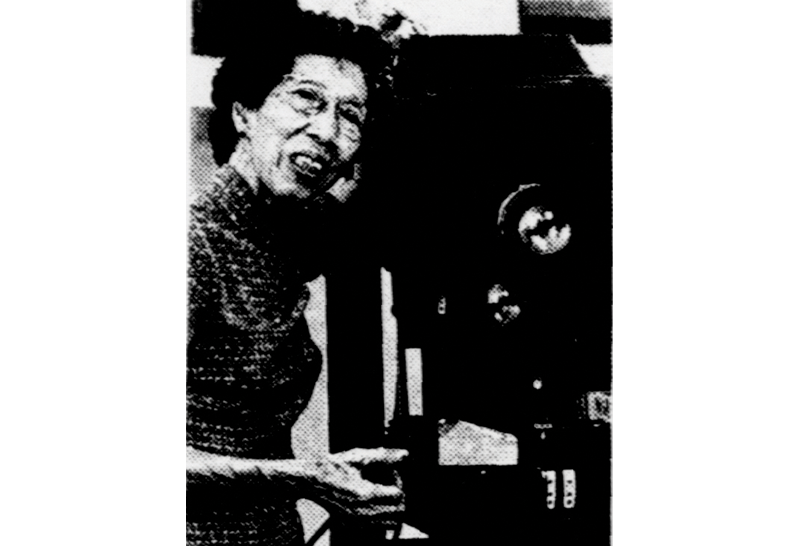

Wun Chek Hoi of Chew Photo Studio

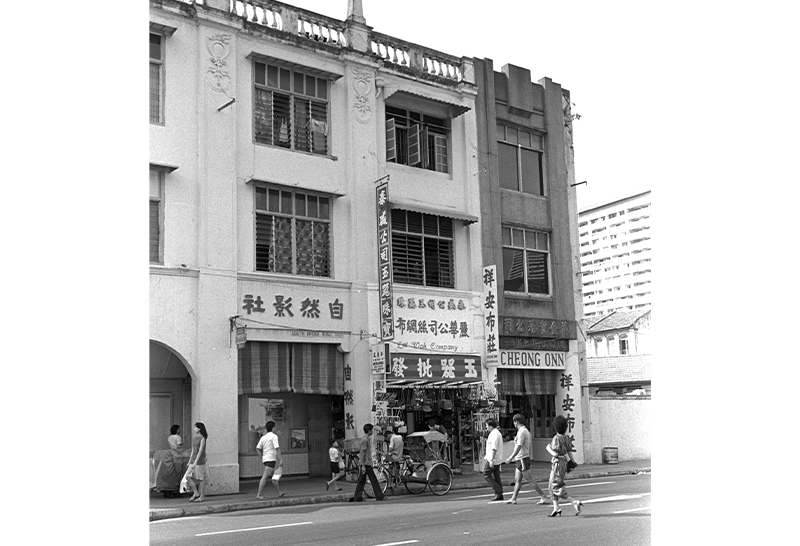

Born in China in 1919, Wun Chek Hoi was a Cantonese practitioner of studio photography who came to Singapore with her parents when she was three and began her apprenticeship during the Japanese Occupation. Before the war, Wun’s father operated a lodge and knew a few Cantonese friends in studio photography. During the Occupation, they advised him to open a studio and employ his nine children to keep them productively occupied. By having them work in the studio, he also hoped that they would not be asked to work for the Japanese authorities. With the help of his friends, Chew Photo Studio (自然影社) was established on 1 April 1942 with its main branch at 230 South Bridge Road.3

By September 1942, Chew Photo Studio had been appointed by the Malaya Sumatra Romu Kanri Kyokai (Labour Control Office of Malaya and Sumatra) as one of its official photographers, with branches on North Bridge Road, Serangoon Road, Joo Chiat Road and Upper Serangoon Road. There was also a branch called Smile Studio at the New World amusement park.4

At the time, Wun was already in her early 20s and of marriageable age. However, she was worried about her mother who had suffered much hardship when she had to look after her many siblings; now, she had to contend with bringing up her own children. Wun felt that getting married and starting her own family would add to her mother’s burdens. As the eldest among nine children, Wun decided not to get married but to work in the family business and help her parents instead.5

At first, Chew Photo Studio hired experienced practitioners and photographers while Wun and her siblings served as apprentices. In those days, Chinese-owned photo studios operated on a strict hierarchical system that governed relationships between employees of different seniority and apprentices. Despite being the owner’s children, Wun and her siblings were not given preferential treatment. They were expected to “wash the floor, clean the toilet, do everything, pour tea for the sifu [teacher-mentors] to drink, wait on them”.6

The experienced employees did not teach Wun and her siblings in a formal fashion. Instead, Wun was told to observe how they worked and pick up the skills by herself. But whenever she stood behind the photographers to see what they were doing, she would be shooed away for blocking the light. Undeterred, Wun offered to move chairs around the studio to steal glimpses of how they operated the camera. Over time, Wun acquired her knowledge of photography through these stolen moments of “tutelage”.7

After an extended period, Wun felt reasonably confident that she could take a good photograph. One day, when the senior employees were out for lunch, a customer turned up at the studio. When she stepped forward to help, the customer was sceptical because Wun was female. But Wun assured the customer that if her work was unsatisfactory, he could come back and have the photograph retaken by the photographer of his choice. “At the time, there was no woman who worked as a photographer and, of course, the customers lacked confidence,” Wun explained. Thankfully, the customer was pleased with her shot and that was when Wun realised she had acquired the basics of photography.8

However, there were still many things to learn in studio photography. Wun added that darkroom work, especially developing negatives and printing images, was the hardest to pick up.9 Nevertheless, Wun’s diligence and perseverance ensured that she would become well versed in all aspects of studio work.

After the Japanese Occupation, the experienced operators left to start their own businesses, leaving Chew Photo Studio to be managed entirely by the Wun family. Over time, the main studio on South Bridge Road became an iconic presence in Chinatown. In the 1960s, the studio expanded into the adjacent unit to cater to increasing customer demands, and air conditioning was also introduced to provide greater comfort to customers.10

The business peaked between 1963 and 1975. During auspicious days when Chinese couples held their weddings, there would often be a long queue outside Chew Photo Studio. Their record was photographing 42 couples in a day.11

Wun was also very popular among Hindu customers. As the studio was located beside the historic Sri Mariamman Temple, many couples and their families and friends would visit the studio to have their photographs taken after their wedding ceremony at the temple, insisting that Wun helm the camera.12

In the business of studio photography, keeping up with the latest technology and changing customer tastes was crucial. As Wun and her siblings aged, it became harder to keep up with the relentless pace of innovation and competition. In late 1994, after more than half a century in business, Chew Photo Studio closed for good.13

In a 1991 interview, Wun downplayed her sacrifices for the family and her status as a pioneering studio practitioner. Her satisfaction came simply from seeing her siblings gainfully employed in proper work. “Please don’t say that I am great, this is heaven’s plan [for me],” she said.14

Si Jing and Popular Photography

In 1990, Ng Soo Lui, who was born in Singapore in 1934, started publishing a series of articles in Lianhe Zaobao (联合早报). These writings, under the penname Si Jing, were mainly about her coming-of-age years in Chinatown and various aspects of Cantonese culture and traditions. Her writings also made references to her involvement in popular photography during the 1940s and 1950s, offering insights from a woman’s perspective.

Si Jing was born into a poor family. When she was three, Si Jing was given to Ai, a domestic servant or majie,15 who worked in a leisure house as the maid of courtesans. Years later, Si Jing realised that Ai had used different ways to enslave her so that she would become her money-making tool in the future. Fortunately, as Si Jing grew older, her average looks saved her from a life of prostitution. When Singapore fell to the Japanese in February 1942, Ai sent nine-year-old Si Jing back to her birth family.16

After the Japanese Occupation, Si Jing’s mother kept her promise to send her to school for at least two years. In 1945, Si Jing, who was already 12, enrolled for primary one at Yeung Ching School.17

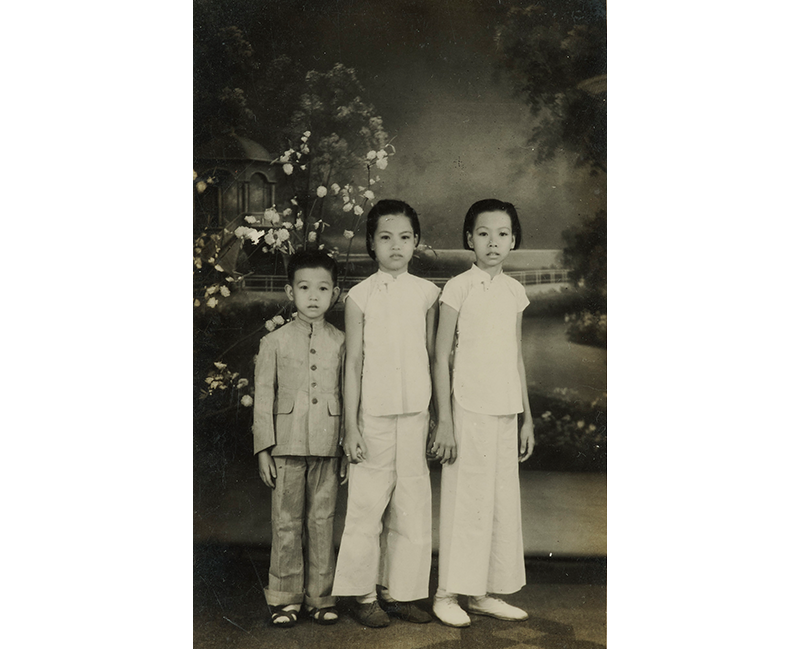

Her mother worked as a seamstress and during the lead-up to the Lunar New Year in 1946, received many orders to tailor new clothes. On the morning of New Year’s Eve, after completing her final order, Si Jing’s mother waited until the reunion dinner for the customer to collect it. With that small payment, she rushed to the fabric stalls on Smith Street to buy several yards of the “cheapest and coarsest white cloth”.

Working through the night, she sewed new clothes for her two daughters. When Si Jing wore her new samfoo (or samfu; a traditional two-piece outfit comprising a top and trousers) the next morning instead of the usual hand-me-downs, her mother’s face lit up with a rare smile. To commemorate the special occasion, Si Jing and her siblings visited a photo studio to have their photograph taken – a common Lunar New Year tradition among families.18

By the second half of 1947, Si Jing’s family finances had become so dire that her mother asked her to stop schooling. Tragedy struck later that year when her mother died in her sleep. Nonetheless, Si Jing’s father allowed her to remain in school until the end of 1948.19

Si Jing got to know her future husband, Huang Da Li, because their fathers were old friends. By the late 1940s, Si Jing and Huang had developed feelings for each other and like many young people in Singapore and Malaya at the time, they went on outings to the countryside. These excursions were especially popular among Chinese-educated students who often took photographs to commemorate their trips.20

Huang and his younger brother earned a decent income by offering photography services at these outings. Later, when Huang gave Si Jing a camera, photography became another reason for their Sunday dates. They walked “along the entire West Coast and took pictures of mangrove swamps, prawn ponds, the jetty in the evening sun, fishing boats at dusk, and huts on stilts among tall coconut trees”. On Si Jing’s 18th birthday, the couple visited Peirce Reservoir.21

Huang and Si Jing tried their hand at salon photography. With its focus on technical excellence and aesthetic beauty, salon photography (or pictorialism) was the dominant framework of art photography in Singapore and Southeast Asia in the 20th century. Huang’s images were exhibited at the Singapore Art Society’s Open Photographic Exhibition in 1951, 1952 and 1953, while Si Jing’s submission, a photograph of Clifford Pier titled “Morning”, was exhibited in 1952.22 This exhibition marked both the highlight and her brief foray into the male-dominated world of salon photography before family responsibilities took precedence.

The people and scenery Si Jing and Huang encountered during their dates became subjects in their pursuit of salon photography. They also modelled for each other’s portraits. Huang actually submitted a photograph he had taken of Si Jing at Peirce Reservoir perched on a railing snapping a picture to the Open Photographic Exhibition in 1952, but it was not selected.23

For Si Jing and Huang, photography served as a leisure activity, a tool of courtship, a means of income and a way to indulge in the aesthetic pleasure of salon photography. On their engagement day in either late 1951 or early 1952, they used a self-timer to take their engagement photograph at the Botanic Gardens. It shows Huang holding Si Jing’s shoulders from behind, with her head tilted back in a loving gaze at her fiancé. They did not show the image to anyone at the time as the pose was considered too intimate in the 1950s.24

Huang and Si Jing were married on 8 July 1952 and held their wedding dinner at the Great Southern Hotel. Following the trend for Chinese weddings at the time, they likely had their wedding photograph taken at a photo studio that same day. In 1953, Si Jing and her family moved into a new Singapore Improvement Trust flat in Tiong Bahru.

In 2002, Si Jing donated her personal collection of photographs to the National Museum of Singapore. Among these are a few showing the interior of her Tiong Bahru flat. One shows the dining table with a cabinet beside it and above the cabinet on the wall is the framed photograph of Clifford Pier exhibited at the 1952 Open Photographic Exhibition.

Chew Lan Ying, the Pioneering Photojournalist

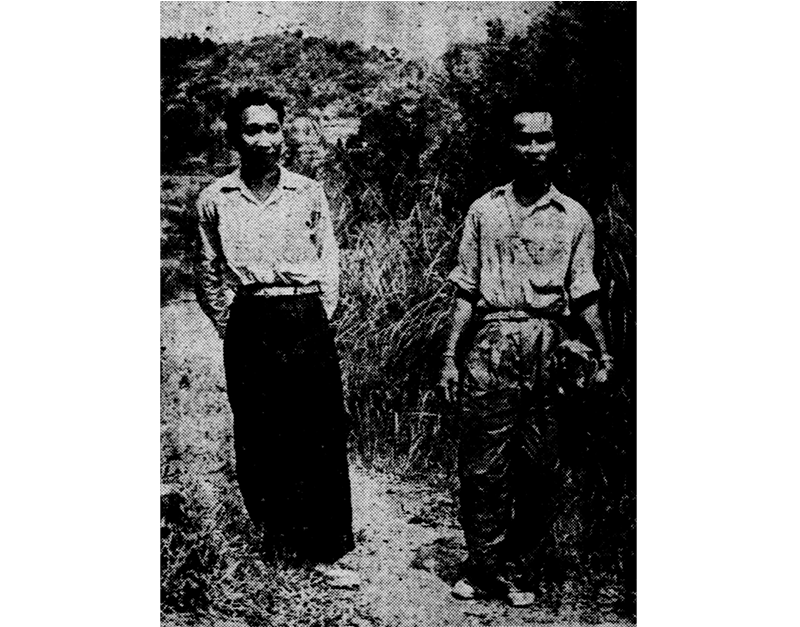

At the end of 1955, the sleepy town of Baling in Kedah was thrust into the spotlight when Tunku Abdul Rahman, first chief minister of Malaya, and Chin Peng, secretary general of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP), met for peace talks there. In the lead-up to the meeting, MCP’s deputy head of propaganda, Chen Tien, and courier guide, Lee Chin Hee, turned up at the tin-mining village of Klian Intan in northern Malaya on 17 October 1955 to begin preparatory talks with government representatives.25 Their sudden appearance caught newspapers in Malaya and Singapore unawares as they had not dispatched any journalists in advance.26

Subsequently, the newspapers stationed their photographers and journalists at Klian Intan and nearby Kroh (present-day Pengkalan Hulu), hoping to catch a glimpse of the shadowy party members. Chew Lan Ying was the only female photographer covering the peace talks. A veteran journalist remembered Chew “often wearing t-shirt and long pants, sporting a short haircut, totally in men’s attire”. She stood out from the rest, carrying several cameras on her.27

Kuala Lumpur-based Chew was a Cantonese photographer whose work first appeared in Nanyang Siang Pau (南洋商报) in early 1955. After the initial preparatory talks on 17 October, the newspaper felt confident enough to send Chew to remote Klian Intan. While other journalists would show up occasionally, Chew positioned herself daily at the mountain path Chen Tien had previously used to reach the village. Although her decision was a gamble as Chen could have taken other paths, her persistence paid off. On 17 November, a month after the first meeting, Chen Tien and Lee Chin Hee took the same route and appeared unannounced at Klian Intan for the second round of preparatory talks.28

Chew captured their approach to the village in a set of exclusive photographs published in Nanyang Siang Pau the following day.29 This cemented her reputation as a tenacious photographer who could stand her ground against men in the competitive field of photojournalism. On 29 December 1955, Nanyang Siang Pau published a photo spread on its front page covering the Baling talks.30 The photographs taken by Chew and two other colleagues were prominently featured.

Like her peers of that era, Chew was a versatile photographer who was assigned by Nanyang Siang Pau to take pictures at different events and occasions. She photographed political affairs of colonial and newly independent Malaya, as well as the cultural events and meetings of business and clan associations of the Chinese community. She did not shy away from gory crime and accident scenes. Apparently, she impressed Tunku Abdul Rahman so much that he would occasionally introduce her to foreign guests at official events.31

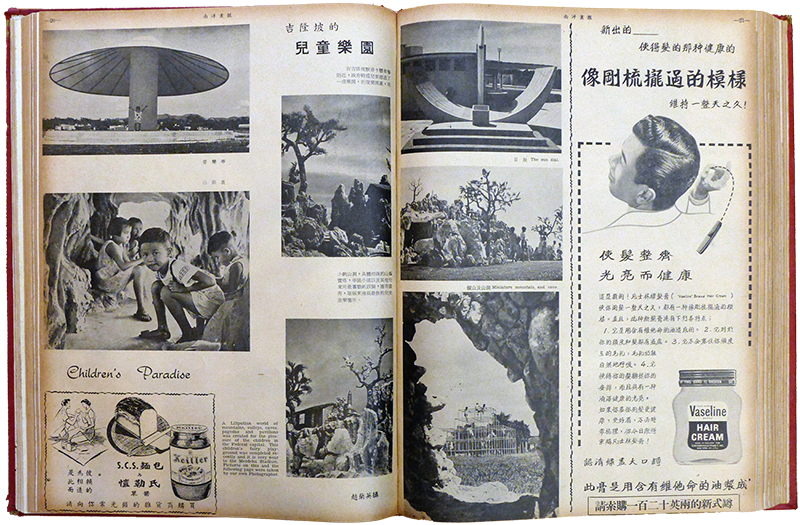

Between 1957 and 1965, the newspaper published Nanyang Monthly (南洋画报), a pictorial periodical that enjoyed strong readership.32 Its inaugural issue sold over 11,000 copies, breaking sales records for pictorial periodicals in Singapore and Malaya.33 Chew contributed to photo spreads in the periodical, including a notable two-page special in issue 10 (April 1958) featuring the newly completed Merdeka Park in Kuala Lumpur.34 Her photographs captured iconic sights, including the Merdeka Sundial, the psychedelic mushroom-shaped bandstand, and miniature caves where children played hide-and-seek.

When Abdul Razak Hussein, prime minister of Malaya, made a diplomatic visit to Thailand in June 1959, Nanyang Siang Pau sent Chew to cover the event.35 Her panoramic photographs were featured in a multi-page spread in issue 27 (September 1959) of Nanyang Monthly, offering readers a different visual experience of Abdul Razak’s activities and reception in Bangkok while highlighting the grandeur of the city’s sights.36

Beyond news photography, Chew participated in salon photography as a member of the Photographic Society of the Federation of Malaya. In April 1957, she joined 11 other society members on a road trip to the east coast of Malaya to photograph life in the fishing villages. They brought along prints to hold exhibitions and also interacted with photography enthusiasts from the area.37

Interestingly, a submission by Chew was selected for the inaugural National Photographic Art Exhibition in China at the end of 1957.38 The selected photograph featured two fishermen from the Malayan east coast mending their net, with the sun casting long shadows in the foreground. The image might have been captured during the excursion.

In 1958, Chew married Lee Yue Loong, a fellow photojournalist at Nanyang Siang Pau.39 Lee owned Dragon Photo Service on High Street, which handled photo commissions as well as developing and printing work.40 After her marriage, Chew worked at their photo business until her husband’s untimely demise in 1970.41 Her contributions to Nanyang Siang Pau decreased significantly after 1960.

Forgotten Women in Photography

While all three women – Wun Chek Hoi, Si Jing and Chew Lan Ying – were drawn to photography for different reasons, their family or future husband played an important role in their foray into photography. Typically, married women had domestic responsibilities which limited their professional development. For Wun, who remained single, her family’s traditional studio business struggled to adapt to Singapore’s rapid modernisation, eventually becoming outdated in a country driven by urban renewal.

These female pioneers have been largely forgotten except for Si Jing, whose work has been uncovered and shown in a recent exhibition at the National Gallery Singapore. Today, there are more female photographers than in the 1940s and the 1950s. Hopefully, there will be newer connections fostered between the contributions of the three women and practitioners of our current generation.

Zhuang Wubin is a writer, curator and artist. He has a PhD from the University of Westminster (London) and is a former National Library Digital Fellow (2023). Wubin is interested in photography’s entanglements with modernity, colonialism, nationalism, the Cold War and “Chineseness”.

Zhuang Wubin is a writer, curator and artist. He has a PhD from the University of Westminster (London) and is a former National Library Digital Fellow (2023). Wubin is interested in photography’s entanglements with modernity, colonialism, nationalism, the Cold War and “Chineseness”.Notes

-

Wun Chek Hoi, oral history interview by Jesley Chua Chee Huan, 5 September 1991, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 2 of 3, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 001299), 08:26. ↩

-

Her name was also spelt Chiew Lian Ying in the English newspaper. See “Two Press Photographers Wed in Kuala Lumpur,” Straits Times, 21 February 1958, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Wun Chek Hoi, oral history interview, 5 September 1991, Reel/Disc 1 of 3, 01:05. See also Au Yue Pak 区如柏, “Ziran Yingshe: Ban ge shiji de weixiao” 自然影社 半个世纪的微笑 [Chew Photo Studio: Half a century of smiles], Lianhe Zaobao 联合早报, 1 January 1995, 46. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Page 2 Miscellaneous Column 1,” Syonan Shimbun, 22 September 1942, 2; Au, “Ziran Yingshe.” [New World (opened in 1923) was the first of three amusement parks in Singapore, along with Great World (1931) and Happy World (1937).] ↩

-

Mok Mei Ngan 莫美颜, “‘Kacha’ wushi nian – Yi ge sheyingshi de huiyi” “咔嚓”50年 – 一个摄影师的回忆 [A click and 50 years – Memories of a photographer], Lianhe Zaobao 联合早报, 30 June 1991, 40. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Wun Chek Hoi, oral history interview, 5 September 1991, Reel/Disc 1 of 3, 09:05. ↩

-

Mok, “‘Kacha’ wushi nian.” ↩

-

Wun Chek Hoi, oral history interview, 5 September 1991, Reel/Disc 2 of 3, 08:26; Mok, “‘Kacha’ wushi nian.” ↩

-

Wun Chek Hoi, oral history interview, 5 September 1991, Reel/Disc 1 of 3, 20:03. ↩

-

Wun Chek Hoi, oral history interview, 5 September 1991, Reel/Disc 1 of 3, 04:31; Wun Chek Hoi, oral history interview, 5 September 1991, Reel/Disc 2 of 3, 19:52. ↩

-

Au, “Ziran yingshe.” ↩

-

Au, “Ziran yingshe.” ↩

-

Mok, “‘Kacha’ wushi nian.” ↩

-

Mok, “‘Kacha’ wushi nian.” ↩

-

Majie refers to female Cantonese domestic servants mainly from Shunde, Guangdong province, who took the vow of celibacy and never married. In Singapore and Malaya, they worked in affluent Chinese and European households until at least the 1970s. They typically wore their hair in a single plait down the back or in a bun. ↩

-

Si Jing [Ng Soo Lui], Lotus from the Mud: I Was a Majie’s Foster Daughter, trans. Geraldine Chay, Wong Hooe Wai and Wong Marn Heong (Singapore: Asiapac Books, 2002), 1–28. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 895.18 SI) ↩

-

Si Jing, Lotus from the Mud, 24–25. ↩

-

Si Jing, Down Memory Lane in Clogs: Growing Up in Chinatown, trans. Laurel Teo (Singapore: Asiapac Books, 2002), 130–33. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 920.72 SI); Mok, “‘Kacha’ wushi nian.” ↩

-

Si Jing, Lotus from the Mud, 51–52, 54–55, 58. ↩

-

Si Jing, Lotus from the Mud, 168, 184; Teng Siao See, Chan Cheow Thia and Lee Huay Leng, eds., Education at Large: Student Life and Activities in Singapore, 1945–1965 (Singapore: Tangent, 2013), xxx–xxxi, 117–18, 151, 154, 166–67, 177–78, 194–95, 204. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 373.18095957 EDU) ↩

-

Si Jing, Lotus from the Mud, 184–86. ↩

-

Si Jing used the name of Ng See-Cheng for the submission. ↩

-

For a positive appraisal of this image, which “casts Wu [Si Jing] as heroic”, see Roger Nelson, “Photography as a Collaborative Practice in Southeast Asia,” in Living Pictures: Photography in Southeast Asia, ed. Charmaine Toh (Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2022), 322. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 770.959 LIV) ↩

-

Si Jing, Lotus from the Mud, 189, 191–92. ↩

-

For a brief account of the preparatory meetings between Chen Tien and government representatives leading up to the Baling talks, see Chin Peng, My Side of History (Singapore: Media Masters, 2003), 364–66. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5104092 CHI); Nik Anuar Nik Mahmud, Tunku Abdul Rahman and His Role in the Baling Talks: A Documentary History (Kuala Lumpur: Memorial Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra, Arkib Negara Malaysia, 1998), 15, 23–26. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.504 ANU) ↩

-

Han Tan Juan 韩山元, “Heping shuguang zhao shancheng” 和平曙光照山城 [Peace dawns upon mountain town], Lianhe Wanbao 联合晚报, 13 November 1987, 23. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Han Tan Juan 韩山元, “Xinwen zhengduozhan – Hualing hetan waiyizhang” 新闻争夺战—华玲和谈外一章 [The battle for news – An extra chapter of the Baling talks], Lianhe Wanbao 联合晚报, 27 November 1987, 19. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Han, “Xinwen zhengduozhan.” ↩

-

For a reproduction of Chew Lan Ying’s exclusive photographs of Chen Tien arriving at Klian Intan, see Zhuang Zhiming庄之明, “Benbao jizhe zuo zai Rendan huijian Chen Tian Qu biaoshi hetan jingxing shunli” 本报记者昨在仁丹会见陈田 渠表示和谈进行顺利 [Our newspaper reporter met Chen Tien yesterday: He said peace talks were progressing well], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 18 November 1955, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Hualing huiyi xiezhen Wei Malaiya heping dailai jiayin” 华玲会议写真 为马来亚和平带来佳音 [Baling talks pictorial: Bringing good news to the peace in Malaya], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 29 December 1955, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Miao Zi 苗子 [pseud.], “Xingma weiyi de nü sheying jizhe Zhao Lanying” 星马唯一的女摄影记者 赵兰英 [The only female photojournalist in Singapore and Malaya: Chew Lan Ying], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 7 January 1959, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Choi Kwai Keong 崔贵强, Xinjiapo Huawen baokan yu baoren 新加坡华文报刊与报人 [Singapore Chinese newspapers, publications and newsmen] (Singapore: Haitian Wenhua Qiye 海天文化企业, 1993), 176. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RCO 079.5957 CGQ) ↩

-

“Nanyang Huabao di er qi mingri chuban” 南洋画报第二期明日出版 [Second issue of Nanyang Monthly to be published tomorrow], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 31 July 1957, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Jilongpo de ertong leyuan” 吉隆坡的儿童乐园 [Children’s paradise], Nanyang Monthly 南洋画报(April 1958): 20–21. (From National Library, call no. Chinese RCLOS 059.951 NM) ↩

-

“Shouxiang xietong waizhang ding houri fang Tai Jianghui shang youguan liangguo gongtong wenti” 首相偕同外长定后日访泰 将会商有关两国共同问题 [Prime minister and minister of external affairs plan to visit Thailand the day after: Will discuss problems that concern both nations], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 26 June 1959, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Mangu fengguang” 曼谷风光 [Bangkok sights], Nanyang Monthly 南洋画报 (September 1959): 19–21; “Lianhebang shouxiang fang Tai” 联合邦首相访泰 [Federal prime minister’s visit to Thailand], Nanyang Monthly 南洋画报 (September 1959): 12–18. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS 059.951 NM) ↩

-

“Lianhebang Yingyi Xiehui lüxingtuan Qianri dongshen fu donghaian Paishe yucun shenghuo tongshi juxing yingzhan” 联合邦影艺协会旅行团 前日动身赴东海岸 拍摄渔村生活同时举行影展 [The Photographic Society of the Federation of Malaya’s travel group set off two days ago for the east coast to photograph the lives of fishing villages and to hold exhibitions], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 16 April 1957, 11; “Lianhebang Yingyi Xiehui Zudui fangwen donghaian Quandui shiyuren qianri yi chufa” 联合邦影艺协会 组队访问东海岸 全队十余人前日已出发 [The Photographic Society of the Federation of Malaya formed a group to visit the east coast: The group of over 10 people had set off two days ago], Sin Chew Jit Poh 星洲日报, 16 April 1957, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Zhongguo Diyijie Quanguo Sheying Zhanlan Xingma shiwuzhen zuopin ruxuan” 中国第一届全国摄影展览 星马十五帧作品入选 [The First National Photographic Art Exhibition in China: Fifteen works from Singapore and Malaya selected], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 8 January 1958, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Benbao zhu Long sheying jizhe Li Yaolong Zhao Lanying jiehun” 本报驻隆摄影记者李耀龙赵兰英结婚 [Our newspaper’s Kuala Lumpur-based photojournalists Lee Yue Loong and Chew Lan Ying got married], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 20 February 1958, 9; “Two Press Photographers Wed in Kuala Lumpur.” (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Dragon Photo Service,” Advertisement, The Perak 1st Salon of Photography (Ipoh: Perak Photographic Research Society, 1957), unpaginated. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS 779.2 PER-[AKS]) ↩

-

“Benbao Long qianren sheying jizhe Li Yaolong buxing bingshi Sangjia ding jinri jubin” 本报隆前任摄影记者 李耀龙不幸病逝 丧家订今日举殡 [Our newspaper’s former photojournalist in Kuala Lumpur, Lee Yue Loong, died unfortunately after an illness: The bereaved family plans for funeral today], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 30 November 1970, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩