“Majulah Singapura” and Other Love Songs

National anthems often start off as songs for different purposes. Singapore’s “Majulah Singapura” is no different.

By Bernard T.G. Tan

Singaporeans are undoubtedly familiar with our national anthem “Majulah Singapura” (Onward Singapore). But not many are aware of the circumstances under which it was composed, and of the events which shaped it into the national anthem we know today.

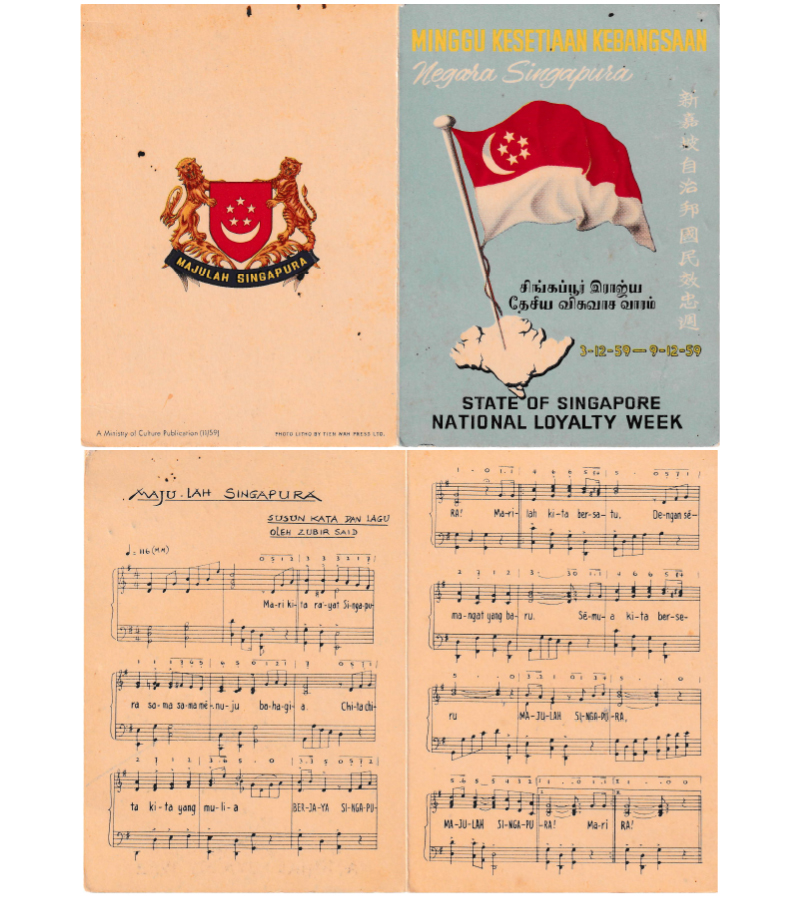

“Majulah Singapura” was not originally composed with the aim of being a national anthem. It was first performed at a concert on 6 September 1958 to celebrate the opening of the newly renovated Victoria Theatre. In 1959, after Singapore had achieved internal self-government, it was chosen to be the official state anthem, though it was a shortened version of the original. It was adopted by the Legislative Assembly as the official state anthem and launched during National Loyalty Week when Yusof Ishak was sworn in as the first Malayan-born Yang di-Pertuan Negara (Head of State). “Majulah Singapura” then became the national anthem when Singapore gained independence on 9 August 1965.

Love Songs of Other Countries

That “Majulah Singapura” did not start off as a national anthem is not as unusual as it sounds. For example, “The Star-Spangled Banner”, which became the national anthem of the United States of America in 1931, was born in the heat of battle during the War of 1812 between the United States and its former coloniser, the United Kingdom.1

The French national anthem, “La Marseillaise”, was composed by Claude-Joseph Rouget de Lisle in 1792 during the years of turmoil of the French Revolution (1787–99).2 Popularised by patriots from Marseille, the song was adopted as the French national anthem in 1795.

The origins of the British royal anthem and national anthem of the United Kingdom, “God Save the King” (or “Queen”), are shrouded in the mists of history but the tune originates from medieval plainchant (a body of chants used in the liturgies of the Western church), with the Elizabethan John Bull as well as Henry Purcell having helped to shape the melody into its present form. The phrase “God Save the King” appears in the earliest English translations of the Bible. By the reign of James II (r. 1685–88), both the lyrics and music of “God Save the King” were well known in a form close to the present version.3

The words for the Japanese anthem, “Kimi Ga Yo” (君が代; His Imperial Majesty’s Reign), originated from a poem written over a thousand years ago in the Heian period (794–1185), which was a passionate love song entreating a loved one to live long and forever. It became the national anthem of Japan during the Meiji period (1868–1912), when the loved one – “Kimi” or “my precious” – represented the Emperor.4 (During the Japanese Occupation of Singapore, people here had to learn this as the new national anthem.)

Closer to home, the adoption of “Negaraku” (My Country) as Malaysia’s national anthem is a fascinating story. A number of versions exist for how the song “Rosalie” became the basis for “Negaraku”. One version is told by Malaysian composer Saidah Rastam in her book, Rosalie and Other Love Songs.5 Sultan Abdullah Muhammad Shah II of Perak was in exile in Seychelles in 1877 when he was invited to visit Queen Victoria in London. The sultan was asked for Perak’s state anthem so that it could be played when the sultan met the queen.

Perak did not have a state anthem at the time, but someone was quick-witted enough to claim that the popular 19th-century French love song “La Rosalie” he had heard on the streets of Seychelles was the Perak state anthem. “La Rosalie”, supposedly composed by the French composer Pierre-Jean de Béranger, was indeed subsequently adopted (with appropriate lyrics) as the Perak state anthem, “Allah Lanjutkan Usia Sultan” (God Lengthen the Sultan’s Age).6

The tune of “La Rosalie” became popular and evolved into the celebrated Malay love song, “Terang Bulan” (Bright Moon). In 1937, the Indonesian film of the same name brought the song to wider audiences. I certainly recall “Terang Bulan” as a song which was universally loved and often heard, becoming part of the soundtrack of my childhood.

A Japanese version of “Terang Bulan” was introduced in the film Marai No Tora. There was even an English version known as “Mamula Moon” (1947), performed by the well-known British band, Geraldo and his Orchestra, and sung by Denny Vaughn. Chinese versions also came into circulation, with perhaps the most famous being 南海月夜 (Nan Hai Yue Ye; Moonlit Night in the Southern Sea), recorded in 1953 by the famed Shanghainese chanteuse Yao Li (姚莉).7

When the Federation of Malaya became independent from British colonial rule on 31 August 1957, a search began for a suitable national anthem. Tunku Abdul Rahman, chief minister of Malaya (later prime minister of Malaysia), convened and chaired a committee for the task. A contest was held and submissions were invited from notable composers such as Benjamin Britten, William Walton and even Zubir Said. All this came to nought, and it was then suggested by the Tunku that the Perak state anthem might be suitable. The committee wrote new lyrics for the new anthem, which was titled “Negaraku”. When the new Federation of Malaysia was formed on 16 September 1963, “Negaraku”8 became its national anthem.

Zubir Said: Composer of “Majulah Singapura”

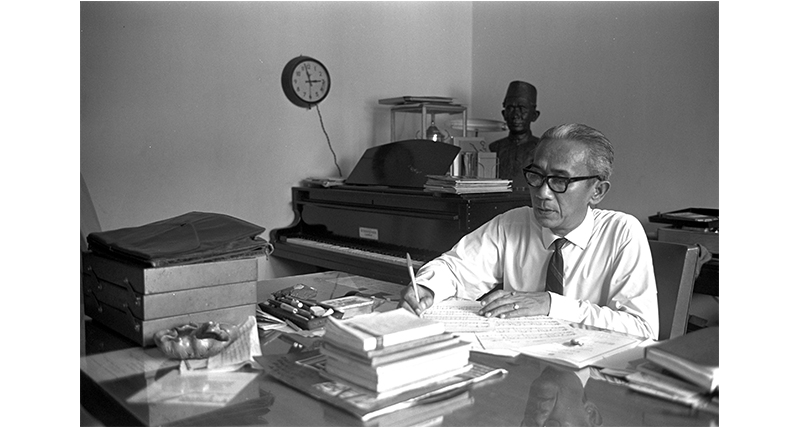

The backstory of how Zubir Said (affectionately known as Pak Zubir; pak means “father” in Malay) ended up composing “Majulah Singapura” is just as fascinating.

Zubir was born in 1907 in Bukit Tinggi, Minangkabau, Sumatra, and his innate musicality manifested itself in primary school when he carved his own flute from bamboo and participated in a band with other flautists. Later, he became the leader of a roving keroncong (a small ukulele-like instrument and an Indonesian musical style) band, performing at weddings and fun fairs.9

Zubir’s father regarded music as haram (forbidden or unlawful in Islam). Seeking freedom from his family to pursue his musical dreams, Zubir left Sumatra in 1928 at the age of 21 on a cargo ship bound for Singapore where he joined City Opera, a bangsawan (Malay opera) troupe, as a violinist. He performed at the Happy Valley amusement park with the troupe, eventually becoming its leader. He also picked up new musical skills such as playing the piano as well as Western musical notation and music theory.10

During the Japanese Occupation, Zubir lived in Bukit Tinggi with his two wives and three daughters. He returned to Singapore in 1947 and joined Shaw Brothers’ Malay Film Productions in 1948, writing songs for their Malay films such as Chinta (1948) and Rachun Dunia (1950).11 He worked with resident Shaw director B.S. Rajhans, recruiting the young P. Ramlee as a playback singer to provide voice dubbing for on-screen songs sung by the actors. P. Ramlee, who later became an icon in the Malay film and music industry, was the playback singer for the male lead Roomai Noor in Chinta.

Zubir wrote many of the songs in Rachun Dunia, starring P. Ramlee and Siput Sarawak. One of these, “Sayang Di Sayang”, is among his most well-known compositions. It was sung by playback singer Rubiah in the film. But perhaps the most famous recording of “Sayang Di Sayang” was by the popular singer Kartina Dahari.

Zubir found greater scope for his musical talents at Cathay-Keris Studio in 1953 and became responsible for all the musical aspects of its films, including the entire composition and scoring of all music.

Invitation from the City Council

By the 1950s, Zubir had become a household name in Malay music, and it was at this time that the Singapore City Council undertook a major renovation of the Victoria Theatre, then the premier venue for concerts and drama. As the rebuilding progressed towards completion, a grand concert was planned to mark the reopening of Victoria Theatre.12

Mayor of Singapore Ong Eng Guan asked Yap Yan Hong, superintendent of the Victoria Theatre, to create a song based on the City Council’s motto, “Majulah Singapura”. On 10 July 1958, H.F. Sheppard of the City Council formally invited Zubir to compose a song for the opening performance.13

Zubir accepted the invitation five days later. He knew that it was not going to be a romantic song but a special kind of song. “So I asked one friend what I should do with the lyrics. Music is quite easy for me. But the words…” he revealed in his oral history interview in 1984. “So the friend says, ‘You must study the policy of the government… and what the public wants. After that you can compose’.” Zubir also realised that the words had to be simple and easily understood by both Malays and non-Malays in Singapore. “So I consult[ed] also an author in language, in Malay language so that I can do it in proper Malay language but not too deep and not too difficult.”14

Zubir must have worked with tremendous speed as the Minutes of the City Council’s Finance and General Purposes (Entertainments) Sub-Committee on 28 July 1958 reported that “A recording of the music is played for the information of the Sub-Committee”.15

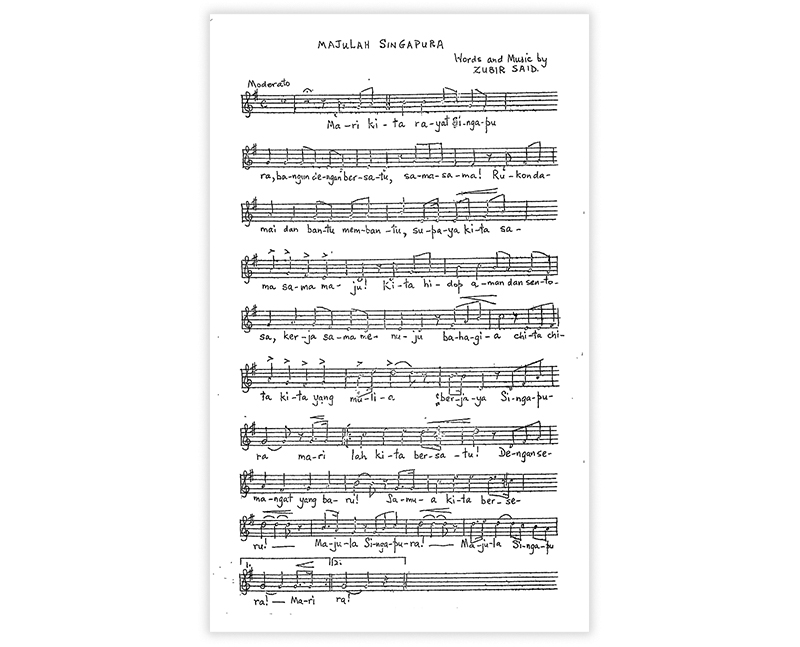

A memo dated 30 August 1958 from Yap to all participants in the opening performance came with a copy of a handwritten score of the song with just the melody and lyrics.16 This score also lacks the familiar fanfare-like introduction, but the first couple of bars contain rests which correspond exactly to the introduction, so it could well have been composed at the same time but omitted from this purely vocal score. However, it is quite clearly in Zubir’s own handwriting as it featured his rather unusual lowercase “p”.

The National Archives of Singapore has a copy of the score, which is currently on display at the Laws of Our Land: Foundations of a New Nation exhibition at the National Gallery Singapore.17 It was very likely scanned from the original handwritten manuscript of “Majulah Singapura” whose whereabouts remain unknown. It is almost certain that this is what Zubir gave to the City Council in response to the invitation of 10 July 1958.

The opening performance of the renovated Victoria Theatre took place on 6 September 1958, and the first item was “Majulah Singapura”, orchestrated by Dick Abell of Radio Malaya.18 The performance by the choir and orchestra of the Singapore Chamber Ensemble was conducted by Paul Abisheganaden, and a Straits Times report on the concert called it “a stirring song, Majulah Singapura (composed by Zubir Said)”.19

“Majulah Singapura” was next heard at the massive Youth Rally convened at the Padang on 23 February 1959 for the visit of the Duke of Edinburgh, performed by the Combined Schools Choir under the baton of Abisheganaden.20 The song quickly found favour with the public, and I was so taken with it that I made a piano arrangement of the song.

Shortening of the Verse

On 3 June 1959, Singapore attained self-government and Deputy Prime Minister Toh Chin Chye was given the task of creating its new symbols of statehood, including the state anthem. Singapore Mayor Ong Eng Guan alerted Toh to “Majulah Singapura” and Toh, on hearing the song, agreed it was highly suitable to be the state anthem. However, he requested Zubir to shorten it first.21

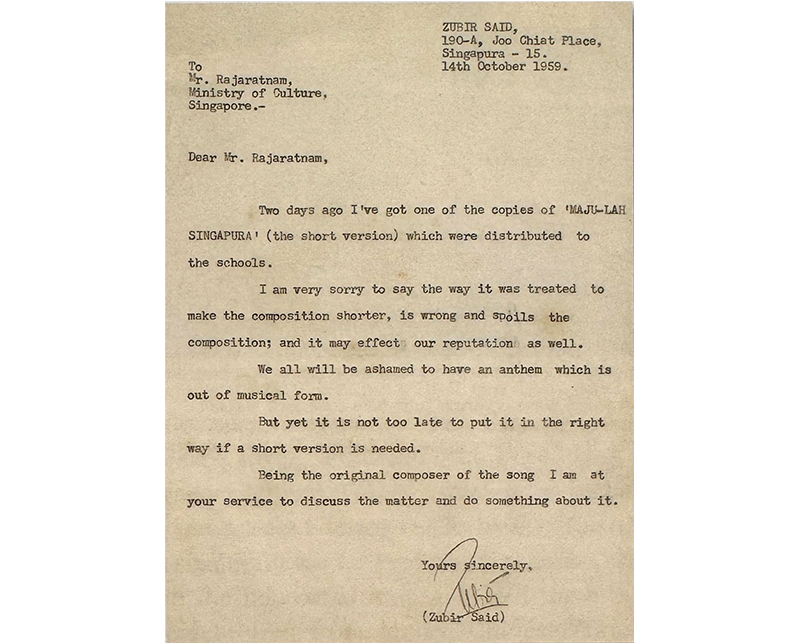

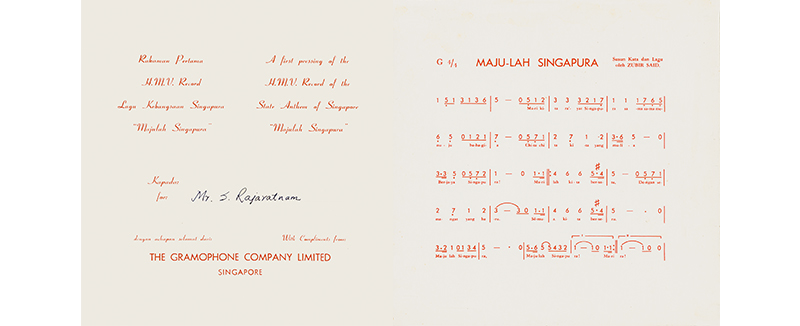

But before Zubir could finish shortening it, it appeared that someone else (whose identity remains unknown) had already done so. Zubir complained in a letter to Foreign Minister S. Rajaratnam on 14 October 1959 that he had seen a copy of this shortened version in a souvenir card sent to schools (which I do recall seeing myself), and that the way it was shortened was “wrong and spoils the composition”.22 As the Singapore State Arms and Flag and National Anthem Bill to adopt the unauthorised version was due to be passed by the Legislative Assembly on the very day Zubir wrote to Rajaratnam, the bill was withdrawn, possibly as a result of Zubir’s intervention.23

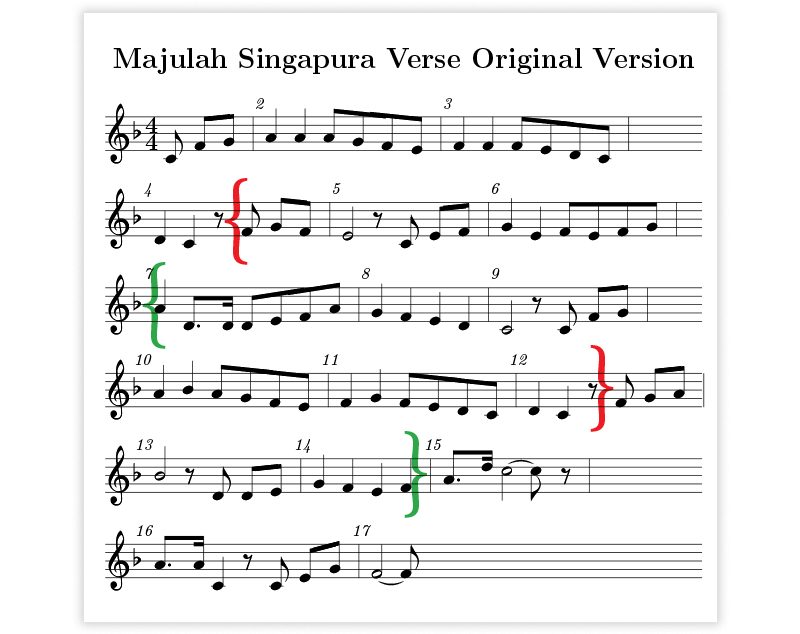

The original version of “Majulah Singapura” consisted of a 16-bar verse and an 8-bar chorus, which was repeated to make it 16 bars. The unauthorised shortening, as I recall, removed eight bars from the middle of bar 4 to the middle of bar 12. In Zubir’s shortened version, he also removed eight bars, but these were bars 7 to 14 instead. His shortened version made more musical sense than the unauthorised shortening. It remains a mystery, though, why someone else was asked to do the shortening without Zubir’s knowledge.

Zubir’s shortened version was adopted by the Legislative Assembly as the official state anthem on 11 November 1959, along with a new state flag and coat-of-arms. The Ministry of Culture issued a new souvenir card bearing the official state anthem as shortened by Zubir, the new state flag as well as the new state arms. Most Singaporeans today are unaware that the national anthem is a shortened version of the original song.24

“Majulah Singapura” as the State and National Anthems

The new anthem was launched during National Loyalty Week which ran from 29 November to 5 December 1959 when Yusof Ishak was installed as the Yang di-Pertuan Negara. “Majulah Singapura”, heard for the first time as the state anthem, was played alongside the British anthem “God Save the Queen”.25

Singapore became part of the new Federation of Malaysia formed on 16 September 1963. While “Majulah Singapura” remained our state anthem, “Negaraku” was adopted as the national anthem as Singapore was now part of Malaysia.26 When Singapore left Malaysia on 9 August 1965, “Majulah Singapura” became the national anthem of the newly independent nation.

The initial official recordings of “Majulah Singapura” were by the Radio Singapore Orchestra and the Singapore Military Forces Band.27 When the Berlin Chamber Orchestra visited Singapore in 1960, they were asked to make a recording of “Majulah Singapura” which became the official recorded version of the anthem for many years.28 Two further recordings were made by visiting orchestras: Japan’s NHK Symphony Orchestra in 1963 and the London Symphony Orchestra in 1968.29

Revised Orchestrations

In 2000, the Ministry of Information and the Arts (MITA; now Ministry of Digital Development and Information) decided to have a new orchestration of the national anthem, and I chaired a committee to do this. I proposed that the key of the anthem be transposed down to the key of F major from G major which would put the highest note at D5 instead of E5, making the anthem easier to sing.30

The version being used then was by the British composer Michael Hurd, and a number of Singapore composers submitted new orchestral arrangements of the anthem. The committee eventually selected the version by classical composer Phoon Yew Tien, who received the Cultural Medallion in 1996. This was decided after a careful evaluation by MITA, which also sent recordings of five different arrangements to selected schools to test out reactions.31

The committee’s decision had to be submitted to the Cabinet for approval, and my colleague at MITA, Ismail Sudderuddin, who had been steering the project, asked me to brief the Cabinet on the project, including why we wanted to change the key of the anthem.32

During the briefing, I was somewhat stunned by a question posed by Minister Mentor Lee Kuan Yew, who said something like: “Would it be possible to have the different versions for orchestra, band and choir in different keys?” Though possible, this is not really desirable. I nervously replied that it was not possible, and fortunately Minister Mentor seemed to accept my somewhat unsatisfactory answer.

Phoon’s version, launched on 19 January 2001, was sung by Jacintha Abisheganaden accompanied by the Singapore Youth Choir. The Singapore Symphony Orchestra recorded seven versions of the new arrangement – ranging from a version for a full orchestra to one for piano.33

All of these recordings were, of course, the shortened version of “Majulah Singapura”, the one we are familiar with today. Few people would have known about Zubir’s longer original composition and even fewer would have heard it. I believe the first time the longer version was publicly performed after 1965 was in 1979. That year, a series of inaugural concerts of the Singapore Symphony Orchestra (SSO), the brainchild of Deputy Prime Minister Goh Keng Swee, was scheduled to begin on 24 January.34

Some months before the concert, I casually remarked to chairman of the SSO, Tan Boon Teik (who was also the attorney-general of Singapore), that Zubir’s original version of “Majulah Singapura” was actually eight bars longer than the official national anthem. He quickly responded that we should play the original version of “Majulah Singapura” at the inaugural concert.

The orchestral score of the national anthem being used at the time was by British composer Elgar Howarth. For the concert, I inserted the missing eight bars into Howarth’s score purely from memory and then orchestrated the inserted bars in the style of Howarth’s orchestration. “The 41-strong orchestra struck the right stirring note from the outset when it played a spirited version of the national anthem with a variation and in a manner few Singaporeans had heard before,” reported the Straits Times the day after the concert.35

As far as I am aware, it would be more than three decades later that the longer version would next be performed in public. In 2015, when Singapore commemorated its 50th year of independence, the Orchestra of the Music Makers, or OMM (I was then chairman of the board), contributed to the celebrations by performing Mahler’s Symphony No. 8 at a concert at the Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay. The OMM’s music director, Chan Tze Law, wanted to conclude the concert with a performance of the original, unshortened version of “Majulah Singapura” followed by the official national anthem using the same choral and instrumental forces as Mahler 8.

I hurriedly scored these two versions as requested by Tze Law, and at the concert, the original version of “Majulah Singapura” was performed and heard by a new generation of Singaporeans. And thanks to the internet, even more Singaporeans have heard the original version as the performance was subsequently posted on YouTube. Since it was uploaded 10 years ago, the performance has been viewed more than 177,000 times.36

The Original Manuscript of “Majulah Singapura”

During my research into the origins of “Majulah Singapura”, I had, as mentioned earlier, come across the correspondence between the City Council and Zubir on the commission to write a song for the reopening of the Victoria Theatre. I am now convinced that the manuscript of the original music and lyrics in the City Council files (attached to the 1958 memo from Yap Yan Hong) is indeed a copy of Zubir’s original manuscript of the song.

A fuller account of the search for the original manuscript has been published elsewhere,37 but I will sketch out the main points of the account. I obtained a copy of Zubir’s manuscript (dated 11 November 1959) of his official shortened “Majulah Singapura”, which became the national anthem, from Rahim Jalil, a retired senior lawyer and owner of Zubir’s Joo Chiat apartment, who had been introduced to me by Winnifred Wong, former principal librarian at NUS Libraries. This manuscript was the basis of the official souvenir card issued by the Ministry of Culture in 1959.38

Comparing the handwriting in this manuscript to the City Council’s copy of the original “Majulah Singapura” manuscript,39 there is a reasonable certainty (as attested to by the Health Sciences Authority’s handwriting expert, Yap Bei Sing) that the two manuscripts were by the same person as they both featured Zubir’s unusual handwritten lowercase “p”.

A Love Song for Singapore

I was born in Singapore in 1943 during the Japanese Occupation, so the national anthem of my birth was the Japanese “Kimi Ga Yo”. Following the return of the British in 1945, my national anthem became “God Save the King” (to become “God Save the Queen” in 1952). When Singapore became self-governing in 1959, “Majulah Singapura” became our state anthem (presumably with “God Save the Queen” remaining the national anthem).

When we became a part of the Federation of Malaysia in 1963, “Negaraku” became our national anthem and after Singapore left Malaysia on 9 August 1965, “Majulah Singapura”, which had remained as our state anthem, finally became the national anthem of the sovereign Republic of Singapore.

As loyal Singaporeans, we think of “Majulah Singapura” as our national anthem, and unlike “Kimi Ga Yo” and “Negaraku”, it never had an existence as a romantic love song. And yet it is indeed a love song – Zubir Said’s love song for his adopted nation – affirming his loyalty and affection for the country in which he had found a meaningful and fulfilled life.

So in “Majulah Singapura”, the same expression of deep affection and affirmation found in love songs is indeed embedded in its lyrics and music by a man who wanted to express his love for the nation that had embraced him so readily. It is therefore fitting that Singaporeans themselves have so readily embraced “Majulah Singapura” as an affirmative love song to our nation.

Listen to “The Making of ‘Majulah Singapura’ as We Know It”, the BiblioAsia+ podcast by Emeritus Professor Bernard T.G. Tan where he talks about the origins of our national anthem.

My heartfelt thanks are due to Eric Chin and Wendy Ang, both former directors of the National Archives of Singapore; Winnifred Wong, former principal librarian, NUS Libraries; Rahim Jalil, retired senior lawyer and owner of Zubir Said’s Joo Chiat apartment; Rohana Zubir, daughter of Zubir Said; and Yap Bei Sing, document examiner, Health Sciences Authority.

Emeritus Professor Bernard T.G. Tan is a retired professor of physics from the National University of Singapore who also dabbles in music. Some of his compositions have been performed by the Singapore Symphony Orchestra.

Emeritus Professor Bernard T.G. Tan is a retired professor of physics from the National University of Singapore who also dabbles in music. Some of his compositions have been performed by the Singapore Symphony Orchestra. Notes

-

“Francis Scott Key Pens ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’” History.com, last updated 27 May 2025, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/september-14/key-pens-star-spangled-banner. ↩

-

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “La Marseillaise,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, 6 June 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/La-Marseillaise. ↩

-

Charles Dimont, “The History of ‘God Save the King’,” History Today, 3, no. 5 (May 1953), accessed 9 July 2025, https://www.historytoday.com/archive/history-matters/god-save-queen-history-national-anthem. ↩

-

Akiko Murakami, “Japan’s National Anthem Was and Is an Ultimate Love Song,” 27 March 2022, https://www.nara-yamatospirittours.com/post/japanese-national-anthem-was-and-is-an-ultimate-love-song. ↩

-

Saidah Rastam, Rosalie and Other Love Songs (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Khazanah Nasional Berhad, 2014), 11–33. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 782.42095951 SAI) ↩

-

Benjamin Wong, “The Fascinating Origins of Malaysia’s National Anthem, ‘Negaraku’,” Lifestyle Asia, 19 August 2024, https://www.lifestyleasia.com/kl/culture/facts-and-history-of-malaysia-national-anthem-negaraku/; Tse Hao Guang, “A History of Negaraku in Seven Rumours,” PR&TA, accessed 11 July 2025, https://www.pratajournal.com/history-of-negaraku. ↩

-

Tse, “A History of Negaraku in Seven Rumours.” ↩

-

Wong, “The Fascinating Origins of Malaysia’s National Anthem, ‘Negaraku’.” ↩

-

National Heritage Board, “Zubir Said,” Roots, last updated 24 October 2023, https://www.roots.gov.sg/stories-landing/stories/zubir-said/story; Rohana Zubir, Zubir Said – the Composer of Majulah Singapura (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2012), 21–27. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 780.92 ROH) ↩

-

Cheryl Sim, “Zubir Said,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 3 September 2014. ↩

-

Low Zu Boon, “Zubir Said and the Golden Age of Singapore Cinema,” Roots, 6 February 2025, https://www.roots.gov.sg/stories-landing/stories/the-bright-lights-zubir-said-and-the-golden-age-of-singapore-cinema/story. ↩

-

Singapore City Council, “Opening Performance/New Victoria Theatre,” 1958. (From National Archives of Singapore, microfilm no. PUB 386 - 11) ↩

-

Letter from H.F. Sheppard to Zubir Said, 10 July 1958. ↩

-

Zubir Said to H.F. Sheppard, 15 July 1958; Zubir Said, oral history interview by Liana Tan, 13 September 1984, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 14 of 23, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000293), 190–91. ↩

-

Minutes of Meeting of the Finance and General Purposes (Entertainments) Sub-Committee, 28 July 1958. ↩

-

Yap Yan Hong, “Opening Ceremony Victoria Theatre” (memo to all participants), 30 August 1958; Zubir Said, “Manuscript of “Majulah Singapura,” attached to Yap Yan Hong’s memo, 30 August 1958. ↩

-

“Laws of Our Land: Foundations of a New Nation,” National Gallery Singapore, accessed 22 July 2025, https://www.nationalgallery.sg/sg/en/exhibitions/laws-of-our-land-foundations-of-a-new-nation.html#ways-to-experience. ↩

-

Singapore City Council, “Opening Performance/New Victoria Theatre.” ↩

-

L.S.Y, “Spotlight on Talent All on One Stage,” Straits Times, 7 September 1958, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Majulah Singapura – by Choir of the Combined Schools,” Straits Times, 16 February 1959, 7; “… But It Was Prince Who Stole Show,” Straits Times, 24 February 1958, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Toh Chin Chye, oral history interview by Daniel Chew, 23 August 1989, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 1, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 001063), 1; “National Anthem,” National Heritage Board, last updated 14 March 2025, https://www.nhb.gov.sg/what-we-do/our-work/community-engagement/education/resources/national-symbols/national-anthem. ↩

-

Rohana Zubir, Zubir Said – the Composer of Majulah Singapura (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2012), 5–6. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 780.92 ROH); National Heritage Board, “State of Singapore National Loyalty Week Card,” Roots, last updated 4 April 2023, https://www.roots.gov.sg/Collection-Landing/listing/1128296?taigerlist=collections ↩

-

“Govt. Withdraws Anthem Bill,” Straits Times, 14 October 1959, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Singapore Chooses Own Flag and Anthem,” Straits Times, 9 November 1959, 1; “500,000 Souvenir Cards for L-Week,” Straits Times, 27 November 1959, 4; Tan Shzr Ee, “Missing: Eight Bars,” Straits Times, 22 January 2001, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Singapore Rejoices: Huge Crowds Throng Padang for Big Parade,” Straits Times, 4 December 1959, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Up Goes the Flag,” Straits Times, 17 September 1963, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Rehearsing ‘Majulah Singapura’,” Singapore Free Press, 28 October 1959, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Jessica Yeo, (NLB), personal communication, 18 April 2016; “Von Benda and Co. Show How to Play ‘Majulah Singapura,” Singapore Free Press, 18 February 1960, 3; “Anthem Gift,” Straits Times, 12 September 1960, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore, “Choir & Orchestra (Song of Singapore) With Narration (Recording Date 12/05/1959),” 1959–1968, sound recording, 14:59. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 2011003748) ↩

-

Loretta Marie Perera, “Majulah Singapura: A Composition of History,” MusicSG, accessed 9 August 2018; Joe Peters, “Pak Zubir Said and Majulah Singapura,” The Sonic Environment (blog), 20 October 2021, http://thesonicenvironment.blogspot.com/2014/08/pak-zubir-said-and-majulah-singapura.html; Tan Shzr Ee, “It’s Easier to Sing Now,” Straits Times 22 January 2001, L6; John Gee, “Grander, More Inspiring Anthem,” Business Times, 20 January 2001, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gee, “Grander, More Inspiring Anthem”; Tan, “It’s Easier to Sing Now.” ↩

-

Tan, “It’s Easier to Sing Now.” ↩

-

Gee, “Grander, More Inspiring Anthem.” ↩

-

“Moment of Calm Before the Debut,” Straits Times, 26 January 1979, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Leslie Fong, “Singapore Symphony Starts on Right Note,” Straits Times, 25 January 1979, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Orchestra of the Music Makers, “Zubir Said – The Singapore City Council Song and National Anthem ‘Majulah Singapura’,” YouTube, accessed 23 July 2025, https://youtu.be/r6kaVWiuJ2U. ↩

-

Bernard T.G. Tan, “The Hunt for Majulah Singapura,” Cultural Connections 4 (2019): 12–28. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 700.95957 CC) ↩

-

Zubir Said, “Original manuscript of ‘Majulah Singapura’ (official shortened version),” 11 November 1959; “500,000 Souvenir Cards for L-Week.” ↩

-

Zubir Said, ““Original manuscript of ‘Majulah Singapura’ (official shortened version).” ↩