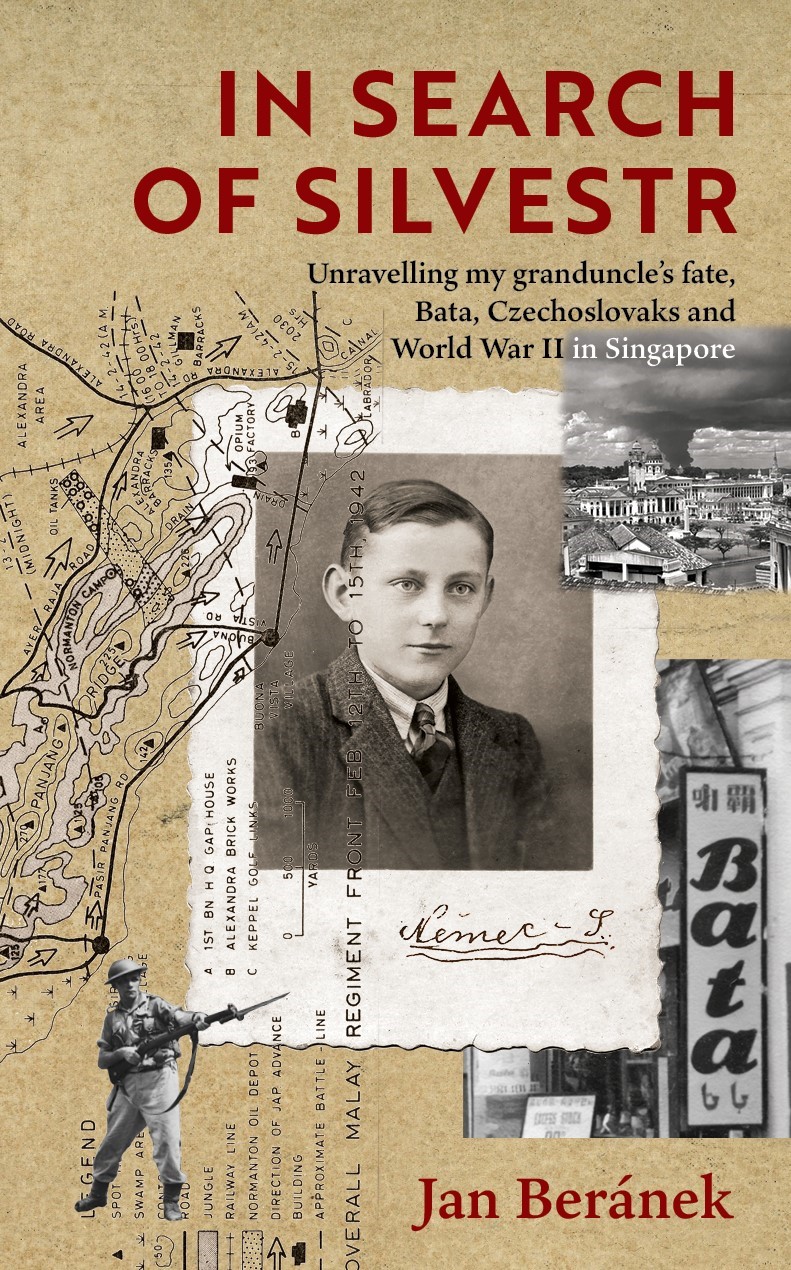

In Search of Silvestr

Sparked by a box of old family documents, Jan Beránek embarked on an eight-year quest that brought him from a small Czech village to modern Singapore to uncover the life of his granduncle who died during the Japanese invasion of Singapore.

By Jan Beránek

In 2017, my mother showed me a box of old family documents. Among them was a bundle of papers relating to Silvestr Němec – my granduncle. Within those pages lay parts of the story of my granduncle’s life. Silvestr was from a small Czech village in central Europe and was sent thousands of miles away to Singapore by his employer, the Bata Shoe Company, on 31 December 1938. Three years later, during the Japanese invasion of Singapore in 1942, he went missing and was presumed dead at the age of only 22.

Silvestr Němec in February 1938. Courtesy of Jan Beránek.

Silvestr Němec in February 1938. Courtesy of Jan Beránek.My family never learnt what happened to him, and I decided to find out more. Thus began my eight-year quest, driven by curiosity and the desire to gain some closure over Silvestr’s fate. Thanks to a dedicated blog I set up, I received useful tips and made new contacts. I joined the Malayan Volunteers Group, an association of the descendants of volunteers in British Malaya. Through searches in archives across several cities and countries (such as London, Prague, Znojmo, Zlín and Singapore), helped by historians from all over and the descendants of Silvestr’s colleagues and friends, I gathered an incredible amount of insight and information on the life of my granduncle.

The steam roller used to modernise the main road of Vémyslice. The house on the left is Silvestr’s home, and the man on the far right is Silvestr’s father. Silvestr is very likely the boy in the hat on the extreme right. Courtesy of Jan Beránek.

The steam roller used to modernise the main road of Vémyslice. The house on the left is Silvestr’s home, and the man on the far right is Silvestr’s father. Silvestr is very likely the boy in the hat on the extreme right. Courtesy of Jan Beránek.One of the most amazing online resources I used was NewspaperSG, a digitised archive of Singapore newspapers by the National Library Singapore, dating back to 1827. The National Library also holds some truly unique documents within its collections such as the book, Bata 1931–1951: 20 Years of Progress in Malaya.1

When I pieced all the disparate information together, a fascinating, colourful and detailed picture emerged, not only of Silvestr’s own life and death, but of a whole community of over a hundred Czechoslovaks who lived and worked in Singapore during the 1930s, the Second World War and the postwar years. I put all this together in my book, In Search of Silvestr (Landmark Books, 2025).

The Bata Shoe Company

My granduncle Silvestr went to Singapore at a very young age, with a mission to establish and develop the business of the Bata Shoe Company in Southeast Asia. It was registered in Singapore in 1931 and opened its flagship store at Capitol Theatre in February that same year. Many might mistake Bata for a Malayan company, but it started as a family business in Czechoslovakia in 1894.

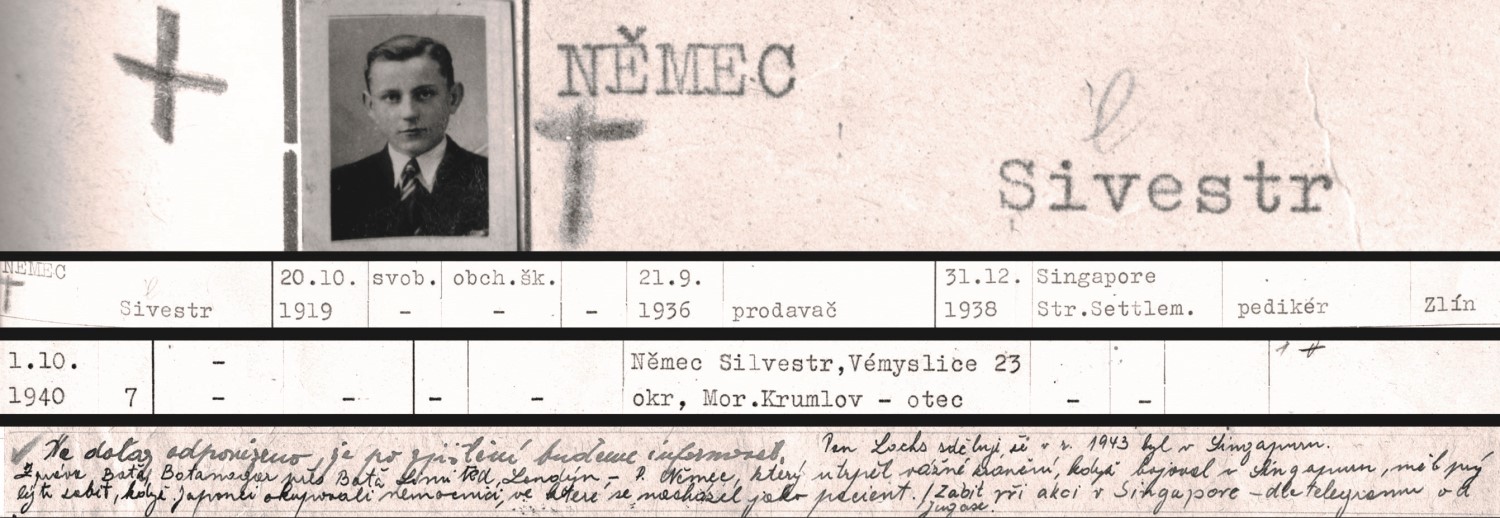

Silvestr’s entry in Bata’s “List of Employees” compiled in Zlín in 1944. Courtesy of Jan Beránek.

Silvestr’s entry in Bata’s “List of Employees” compiled in Zlín in 1944. Courtesy of Jan Beránek.Tomáš Baťa, its founder, had visited Singapore on a business trip in January 1932. During that trip, he announced his vision “to serve Malaya’s five million pairs of feet”.2 In 1934, Bata Shoe Company purchased a rubber plantation in Bukit Tiga in Johor, and three years later launched a large factory in Klang. In 1939, it opened another factory in Singapore and inaugurated its own modern building (which hosted a shoe store, offices and accommodation for Bata workers) on North Bridge Road in 1940. By 1941, Bata was running 150 stores, distribution centres and service points across British Malaya and Singapore.3 I had no idea that the Bata Shoe Company had been so successful globally.

Bata’s flagship store at Capitol Theatre in 1934. Courtesy of Jan Beránek.

Bata’s flagship store at Capitol Theatre in 1934. Courtesy of Jan Beránek. Inside a Bata shoe store in British Malaya, c. 1935. The slogan “Our Customer – Our Master” is one of the most famous credos that people in the Czech Republic still recall today. Courtesy of Jan Beránek.

Inside a Bata shoe store in British Malaya, c. 1935. The slogan “Our Customer – Our Master” is one of the most famous credos that people in the Czech Republic still recall today. Courtesy of Jan Beránek.I found the idea of Czechoslovak people driving Bata’s expansion compelling. One of the reasons for the global success of the Bata Shoe Company was that it created unique and innovative ways of working, including building a strong culture that extended beyond work and which was incorporated into the personal lives of its employees as well. This loyalty and adherence to company culture continued in Singapore.

The Czechoslovak Community and the Second World War

One of my unexpected findings was that the Czechoslovak community in Singapore was painfully divided. Confidential Czech government reports – only recently declassified – documented how several factions were fighting each other, fuelled by differences in backgrounds and loyalties. My granduncle Silvestr was no exception. I believe that one of the contributing factors of this schism was the huge stress caused by the occupation of their home country by Nazi Germany from 1938. While there was still peace in British Malaya at the time, the Czechs would have regularly read about the brutal repressions in Czechoslovakia in the local press.

As the war spread through Europe, some young men – including Silvestr’s colleagues and friends from Bata – left Singapore to join the Czechoslovak army in France to fight for their country, alongside the French and British. Most, however, stayed in Singapore.

Those that remained were not idle. The Czechoslovaks supported the Allied war efforts in many different ways, such as organising charity events and contributing to war funds. Many local newspaper articles mentioned the Bata Shoe Company and also named individuals, including Silvestr.

Most of the Czechoslovak men who remained in Singapore joined the Singapore Volunteer Corps: either the Straits Settlements Volunteer Force (SSVF) or the Local Defence Corps. Silvestr had quite an unusual assignment as he served with the Armoured Cars Company, which was attached to the First Battalion of the SSVF. I found rich details in local newspapers, SSVF yearbooks and several personal diaries about the volunteers’ training, preparations and even some personal reflections in diaries and letters.

One of the hot topics of the day was the difference in pay received by British and European volunteers versus Eurasians and Asians. Such racial discrimination, also observed during training, was an alien concept and puzzling to the Bata Czechoslovaks with their egalitarian ethos.

The Japanese Occupation

As the Japanese attacked Malaya, the war eventually reached what had been painted by the British as the “impregnable fortress of Singapore”. In February 1942, 12 Czechoslovak volunteers, my granduncle Silvestr among them, participated in the historic battle on Pasir Panjang Ridge, alongside Second Lieutenant Adnan Saidi and the Malay Regiment. This was where my granduncle was last seen, and where we lost his tracks. He was most likely wounded and taken to Alexandra Hospital, where he would have fallen victim to the infamous massacre carried out by Japanese troops on defenceless patients and medical staff.4

After the surrender of Singapore, the Japanese were unsure how to treat the Czechoslovaks. Were they allies because Nazi Germany now occupied their country? Or were they, as an active part of the British colony, Japanese enemies? Eventually, those who did not manage to evacuate and evade capture were rounded up in December 1943 and locked up in Changi and Sime Road internment camps until they were liberated when the Japanese surrendered.

During the Japanese invasion and subsequent occupation, no fewer than 10 Czechoslovaks in Singapore lost their lives.

I never thought that my personal quest to discover the fate of my granduncle would bloom into a much larger and richer story of Bata Shoe Company, the Czechoslovak community and the volunteer forces in Singapore. My search had begun in the small market town of Vémyslice in the South Moravian Region of Czechoslovakia and spanned the globe, ending in Singapore where Silvestr lived and probably died.

Jan Beránek’s book, In Search of Silvestr: Unravelling My Granduncle’s Fate, Bata, Czechoslovaks and World War II in Singapore, is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library (call no. RSING 305.8918605957 BER) and for loan at selected public libraries (call no. SING 305.8918605957 BER), the culmination of eight years of research and writing. It is also available for sale at physical and online bookstores.

Listen to ”Searching for Family in the Shadows of War”, the BiblioAsia+ podcast by Jan Beránek where he talks about his search for his granduncle Silvestr Němec.

Jan Beránek is a Czech environmentalist and energy expert. He was born and raised in the Czech city of Brno, where he studied physics and sociology. Jan has worked for several environmental organisations and was also Chair of the Czech Green Party. He currently lives in Amsterdam, working for Greenpeace International as a Director for Organizational Strategy and Development. In his free time, Jan is a keen astronomer and astrophotographer. He was not interested in history until 2017 when he became curious about his family’s roots and started his search for his missing granduncle Silvestr Němec.

Notes

-

See Bata 1931–1951: 20 Years of Progress in Malaya (Singapore: G.H. Kiat, 1951). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 685.3065 BAT) ↩

-

“To Serve Malaya’s Five Million Pairs of Feet,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 1 February 1940, 2. (From NewspaperSG). ↩

-

Jan Beránek, In Search of Silvestr (Singapore: Landmark Books, 2025), 73. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 305.8918605957 BER) ↩

-

In my book I consider other possibilities of how my granduncle might have lost his life, and also share previously unknown, first-hand witness accounts of several Czechoslovaks about the impending Japanese invasion and the horrors of the bombardment of Singapore. ↩