Rediscovering Singapore Before 1800: How Newly Retrieved Sources are Changing the Story

Piecing together the Singapore narrative before Raffles is not easy but the sources are there, just waiting to be discovered.

By Peter Borschberg

In the popular imagination, Singapore’s history still begins in 1819 with the arrival of the British. But the island’s story stretches back far earlier. Long before the arrival of Stamford Raffles, Singapore and its surrounding waters were already a vital node in Southeast Asia’s maritime networks – a place where ships, goods, people and ideas converged. The traces of this earlier history lie scattered across the world, preserved in texts, maps and records that reveal Singapore not as a blank slate, but as a node in a dynamic regional web.

This article draws on my chapter found in the recently published collection of essays titled Reimagining Singapore’s History edited by Matthew Oey (2025).1 In my chapter, I focus on written texts and graphic sources but leave the topic of material culture to Kwa Chong Guan’s separate essay on archaeology.2 The essays in this edited volume were originally presented at the Reimagining Southeast Asian History conference held at the Asian Civilisations Museum in 2023, and show how much more there still is to uncover in Singapore’s deeper and longer history.

Singapore’s Fragmentary Past

It takes more than just curiosity to study Singapore’s history before 1800. Researchers need the skills to interpret evidence, weigh reliability and tease meaning from sources that are often obscure or scattered. My chapter focuses only on European records, especially those written in languages other than English. While there is also a significant but less abundant corpus in Arabic, Chinese, Malay and other Asian languages, those fall outside my skill set but they most certainly deserve separate studies of their own.

Looking back, what is striking is how quickly the field has changed. In the early 1990s, when I had just begun teaching at the History Department of the National University of Singapore, a colleague cautioned me that searching for Singapore’s early history would prove fruitless and that I would end up empty-handed. At the time, many scholars believed Singapore’s history had already reached its apogee, with nothing left to discover. As Matthew Oey notes in his introduction to the volume, this sense of finality reflected a colonial-era mindset that treated Singapore as historically insignificant and irrelevant before the British arrived.

Today, the earlier view that Singapore’s history began only in 1819 feels antiquated. Over the past two or three decades, new research has substantially transformed the field. Fresh sources, bold interpretations and cross-disciplinary collaborations have revealed that Singapore’s pre-1819 past was better documented and more complex than once imagined. Rather than a historical blank slate, the island emerges as an active player in the wider currents of regional and global history.

One of the clearest manifestations of this shift can be seen in Singapore, a 700-Year History: From Early Emporium to World City, first published in 2009. In this edition, the book offered only the sparsest coverage of the centuries between the fall of Temasek-Singapura in the late 14th century and the arrival of the British in 1819.3 A decade later, the 2019 edition, Seven Hundred Years: A History of Singapore, published by the National Library Board and Marshall Cavendish Editions expanded this section substantially, although important gaps still remained, especially in relation to the 15th and 18th centuries.4 Now, with a third edition due in 2026, readers can expect to see Singapore’s early history woven into a seamless seven-century narrative.

So what explains this transformation? What discoveries and breakthroughs have deepened our understanding of pre-1819 Singapore? And what challenges continue to confront researchers as they piece together Singapore’s fragmentary past? The answers lie in the painstaking study of surviving texts, maps and records, as well as in the new questions scholars are asking about Singapore’s role within the regional and global networks of c.1300–1824.

New Sources Behind the New Story

Reconstructing Singapore’s history before 1819 is no simple task. The challenge has never been a lack of interest, but rather a shortage of skills and the weight of bias. For too long, research leaned heavily on English-language texts, leaving much of Europe’s documentary record untouched. Unlocking these early traces requires specialised training: fluency in multiple European languages, mastery of their pre-modern forms and palaeography (the art of reading centuries-old handwriting). Before the internet streamlined and facilitated access, the work could be punishingly slow. Tracking down scattered manuscripts, cross-referencing obscure passages and piecing together fragmentary reports often took decades of patience and persistence.

The surviving European materials that touch on Singapore and its surrounding waters fall broadly into four categories: conventional and unconventional sources, each in text or graphic form.

Conventional sources include the familiar: travelogues, letters, missionary accounts, treaties and official reports by colonial authorities or agents of the British East India Company. Some were written to dazzle readers back home in Europe with vivid – sometimes exaggerated – tales of the East. Others, composed for confidential circulation, offer more sober, carefully weighed assessments.

Yet not all evidence comes neatly packaged as reports or correspondence. Some of the most intriguing insights lie hidden in what might be called “unconventional sources”: maps, charts, glossaries, dictionaries, encyclopedias and even works of fiction. These materials reveal how Europeans, often armed with only secondhand knowledge, tried to make sense of Singapore and its region.

Reference compendia, for instance, recycled outdated information long after it had ceased to be accurate. A mid-18th century dictionary might still describe a “great city” of Sincapura at the tip of the peninsula, centuries after such a large settlement had faded. Phantom cities continued to appear on maps and charts well into the 18th century; Sinosura, a city supposedly lying east of Singapore, was one such example. The error surrounding its existence has been traced to a misreading of Luís Vaz de Camões’ Portuguese epic poem, Os Lusíadas (The Lusiads), first published in 1572.5

The expansive Grosses vollständiges Universal-Lexicon aller Wissenschafften und Künste (Great Complete Universal Lexicon of All Sciences and Arts), an 18th-century German reference work in 68 volumes by the bookseller and publisher Johann Heinrich Zedler, offers a telling example. It contains multiple entries on Singapore, under different spellings, reflecting how the name circulated across European scholarship. More than that, it shows the way knowledge was compiled: snippets borrowed from older works and stitched together by researchers who often had no personal, firsthand access to the places they described.6

Far from curiosities, these unconventional traces matter. They remind us that Singapore existed in the European imagination and circulation of knowledge long before Raffles – and that even secondhand echoes helped shape how the island was placed within the wider global networks of knowledge.

In 1720, Daniel Defoe, the author of Robinson Crusoe, published The Life, Adventures, and Piracies of the Famous Captain Singleton, a novel that cast the Singapore Strait as one of the world’s most dangerous waterways. Pirates, storms and treacherous waters turned every crossing into a deadly gamble. Though fictional, Defoe’s tale reflected how Europeans of the time imagined the region: distant, perilous and impossible to ignore.7

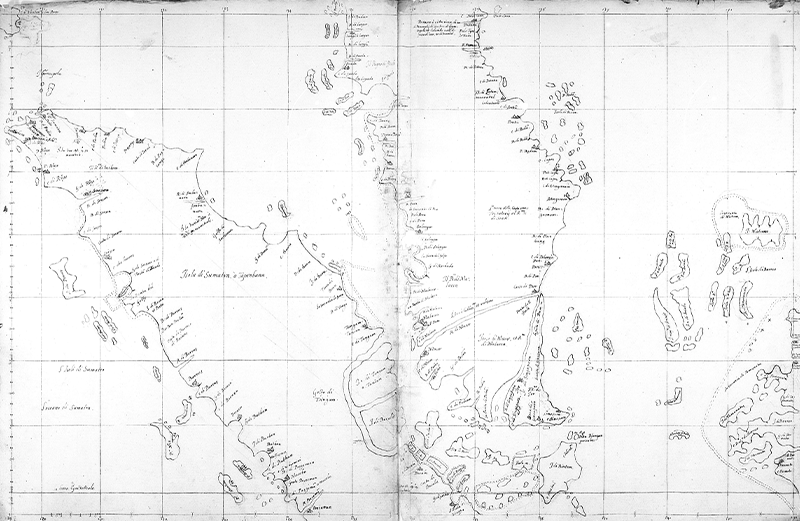

Maps and charts carried the same mixture of knowledge and conjecture. For sailors, these were working tools, noting reefs, anchorages, freshwater springs and ports of call. Yet they also served as repositories of rumour, copying forward old reports long after their underlying realities had eclipsed. A single map might plot the contours of the strait while also speculating about trade routes or repeating references to a “great city” that had long ceased to exist. Read alongside written accounts, these charts reveal not only geography but also the evolving ways by which Europeans sought to comprehend Singapore and its surrounding waters.

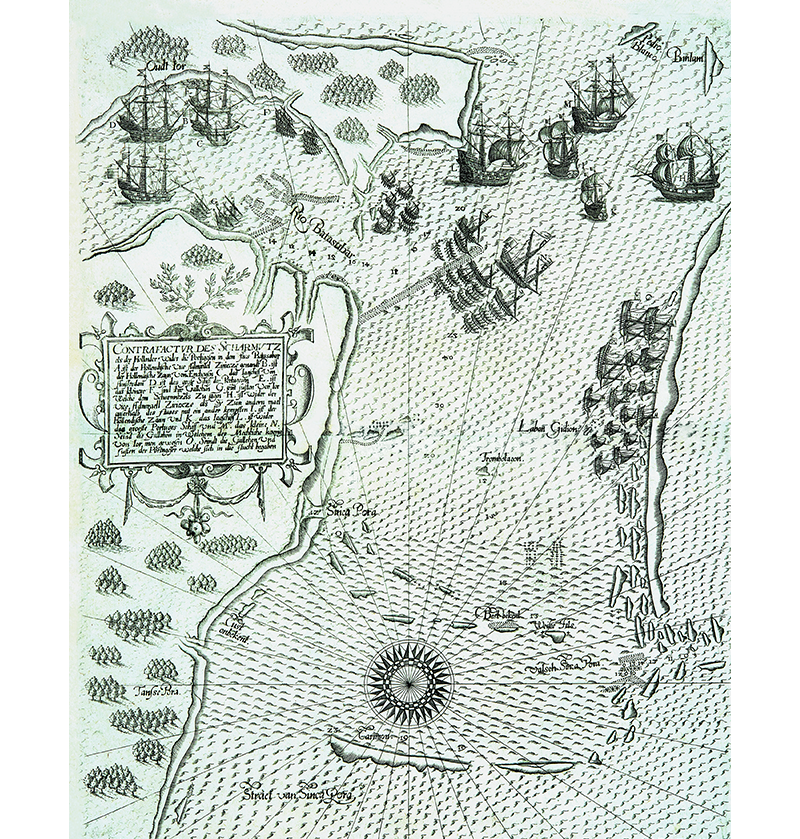

Illustrations extended this visual record. Mariners and ship’s officers sketched flora, fauna, settlements and people, often with as much invention as observation. While most surviving examples date from after 1750, a few earlier engravings stand out. Two from the workshop of the German publisher Theodor de Bry are especially striking. The first, Contrafactur Des Scharmutz Els Der Hollender Wider Die Portigesen in Dem Flus Balusabar (Chart of a Skirmish Between the Dutch and the Portuguese in the Balusabar River; 1606), schematically depicts the battles between Dutch and Portuguese naval forces near Singapore in 1603.8

The other, engraved in 1607, shows Raja Bongsu of Johor, dressed in elaborate Turkish-style robes, in his galley (prahu; a type of boat propelled solely by oars) heading towards the Dutch flagship Zierikzee to meet with Vice-Admiral Jacob Pietersz van Enkhuysen after the battle against the Portuguese in the Johor River and Singapore Strait in 1603. The left of the etching shows a small part of a European-looking city that may have been intended to represent Singapore.9

For all their embellishment, such works are among the earliest surviving European attempts to picture Singapore and its environs. While these blur the lines between record and imagination, they also demonstrate how much can be gleaned from unconventional sources. Taken together, they form part of the mosaic from which Singapore’s pre-1819 history can be reconstructed. Each fragment – however flawed – adds insights, helping to restore the island’s place on the larger regional and global stage.

Unexpected Finds in Unexpected Places

Do new sources still surface? Absolutely – but not in the archives and libraries one might expect. These institutions in London, Lisbon and The Hague have long been trawled for evidence. Real surprises now emerge from smaller or unexpected institutions, monastic libraries, private collections or overlooked manuscripts.

Consider Robert Dudley’s maritime encyclopedia, Dell’Arcano del Mare (On the Secret of the Sea), published in 1645–46. A manuscript copy preserved in the Bavarian State Library in Munich contains a 1636 map, also by Dudley, where multiple features – a settlement, a river, a bay, a strait and a cape – are all marked with the name “Singapura” in various spellings. Such clustering of the name on a single map specimen is unusual and signals the island’s weight in the European imagination.10

Or take the Codex Castelo Melhor, a privately held collection of Portuguese navigational instructions.11 Recently transcribed, it offers something exceptionally rare: sailing directions for the “New Strait of Singapore”, running from the northeastern tip of today’s Sentosa down along the island’s southwestern coast. Most early accounts focus on the Old Strait, the passage between today’s Sentosa and the harbourfront area. This new detail adds a fresh layer of navigational knowledge to a familiar name.

Even more surprising is the diary of Bremond, a French surgeon aboard the naval vessel L’Oiseau during a voyage to Siam (now Thailand) from 1687–88, which was sold at auction in 2023 and is now held in the National Library of Australia. While best known for recording an early European sighting of Australia, it also contains a brief but telling note of the warship passing through the Singapore Strait in December 1687. The entry records a lull – or absence – of wind that delayed the ship’s westward progress to Pondicherry (or Puducherry) in India.12 It was likely during this pause that the officers took measurements and gathered observations, which later informed French maps of the Singapore Strait and substantially shaped French cartographic representations well into the mid-18th century.

Each of these discoveries underscores a vital point: archival work is never really finished. New fragments and voices continue to emerge, uneven in detail but often rich in possibilities. The thrill of the hunt lies in knowing that the next overlooked manuscript – whether in a monastic library or a private sale – could still substantially impact the way we understand Singapore’s pre-1800 story.

What Did “Singapura” Mean?

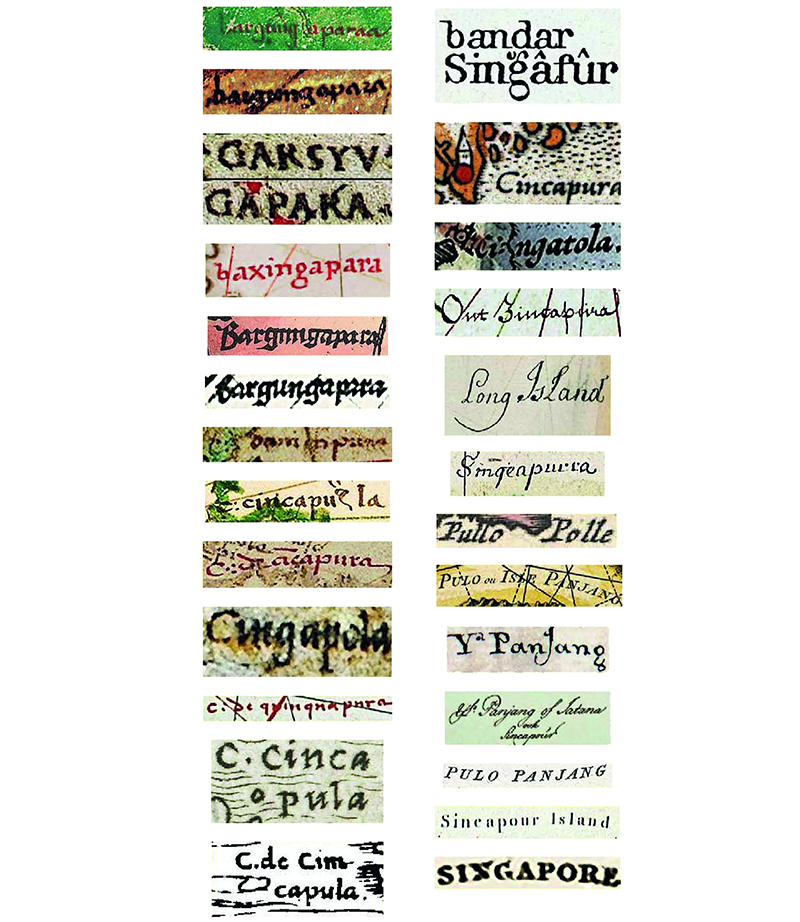

Unlike Temasek, which as a place name never entered European records, “Singapura” appears frequently but not with a single, fixed meaning. Over three decades of research have shown that at least 11 different geographical features around today’s “Singapore” carried this name at one time or another: a settlement, a river, a sandbar, a bay, an island, a kingdom, two distinct maritime straits, a mountain ridge, a cape and even a larger hinterland.

This elasticity of the name “Singapura” makes interpretation a tricky business. A passing reference – “a ship arrived from Singapura” – might point to one of the two straits, the settlement or some entirely different feature. This problem is incidentally not unique to Singapore. Early modern sources use “Malacca” just as loosely: it might mean the city, the Melaka River, the adjacent strait or even the entire Malay Peninsula.

Complicating matters further, there was not just one city or settlement named “Singapura”. Places with the same or substantially similar name appeared in Vietnam, Thailand and Java, while echoes of the name run deep through Indian epic traditions. For historians, the task is not simply to track mentions of the name “Singapura”, but to parse carefully what each reference was actually pointing to.

Solving the Puzzles of Pre-1800 Singapore

How can one craft a historical narrative when a good part of the evidence rests on half-truths, hearsay and hand-me-downs? That is the puzzle of pre-1819 Singapore. Surviving references offer some tantalising glimpses, but they are also riddled with inaccuracies and distortions. Seen in this way, Europeans sometimes viewed Singapore through a type of funhouse mirror: stories recycled, refracted, distorted and stripped of context.

Anachronism is a common trap – treating yesterday’s news as if it were today’s. Batu Sawar, the Johor capital downriver from present-day Kota Tinggi, was destroyed several times in the 1600s and largely faded by the century’s end. Yet 18th-century European compendia continued to describe it as a thriving city, recycling outdated reports long after reality had changed.

Decontextualisation poses another challenge. Information was often lifted from older accounts, stripped of its context and then presented as fresh fact. Geographisch-Statistisches Handwörterbuch (Geographic-Statistical Pocket Dictionary, 1817) by the German geographer and statistician Johann Georg Heinrich Hassel, for instance, describes Singapore as a city of Sumatran settlers ruled by its own king.13 By then – 1817 – no such “city” existed. Hassel was not recording contemporary reality but reworking centuries-old accounts of Parameswara (a fugitive prince from Palembang who usurped power in Singapore), filtered through the published 16th-century Portuguese chronicles of João de Barros and Brás de Albuquerque. In Hassel’s dictionary, legend had quietly morphed into “present-day fact”.

These examples illustrate the delicate work and attention needed to reconstruct Singapore’s pre-1819 past. Each source – accurate or flawed, detailed or fragmentary – must be read carefully, interpreted in context, and weighed against other evidence. Only then can we begin to place Singapore within the broader regional and global networks of the early modern period, restoring the island’s long-forgotten layers of political, economic and cultural significance.

History from Fragments: Reimagining Early Singapore

Piecing together Singapore’s story before Raffles is no simple or straightforward task. Sources are uneven and often contradictory, scattered across centuries and continents, waiting to be coaxed into conversation. Each account is a fascinating shard, yet all are potentially valuable and demand careful evaluation. For historians, assembling a coherent narrative from the late 1300s to the early 1800s is like constructing a mosaic from shards of glass: each piece must be studied, its edges understood and its colours weighed against the rest before a larger picture begins to emerge.

Gaps persist, of course. The 15th and 18th centuries, in particular, remain less studied, and even the best surviving materials resist tidy frameworks. Conventional analytical tools often falter. Forcing the sparse fragmentary sources into rigid analytical models can distort the story they tell. A more fruitful approach is to pay closer attention to language itself, that is, paying close attention to how words, phrases and concepts were constructed in their original context. Reading these fragments critically, with an ear attuned to the rhythm of early modern thought, allows historians to recover not just events, but the way people at the time saw and experienced them.

Singapore in the early modern period was never an isolated place. Studying it in isolation risks misreading its past or projecting modern assumptions back in time. The island existed at the crossroads of regional sultanates, bustling maritime trade routes and the ambitions of distant European powers. Its fortunes rose and fell alongside Majapahit, Siam, Melaka, Johor, Aceh and empires beyond Southeast Asia. To understand its story, one must think in terms of elastic networks rather than fixed borders: shifting currents of commerce, fluid alliances and strategic military moves that dictated the rhythms of daily life.

Only by mapping these connections – and appreciating their complexity – does Singapore begin to take shape in the historical imagination. And even then, understanding is never fixed: each newly discovered letter, map or report reshapes the contours of what we thought we knew, revealing a past that proves to be dynamic, interconnected and fascinating.

Engaging with the Public: History as Conversation

History is not just a scholarly pursuit; it is an ongoing conversation with the public. Audiences are curious, sceptical and sometimes impatient. They stumble upon a fleeting mention of “Singapore” in a centuries-old text and wonder if they have uncovered a hidden treasure. They confront a landscape long assumed empty and may find it hard to imagine that historians can reconstruct a coherent narrative from mere bits and fragments.

Some accuse scholars of embellishing or inventing material; others are frustrated by inaccessible archives and libraries, or texts written in archaic languages. Making these sources accessible through annotated translations, transcriptions and affordable publications is essential. Without accessibility, scholarship risks remaining a private affair, while the public remains tethered to outdated ideas of Singapore’s pre-modern “emptiness”.

Why does this matter? Early modern Singapore was a crossroads, glimpsed only through scattered and often unreliable fragments, yet alive with movement, exchange and human drama. Carefully assembling these fragments does more than recover forgotten details: it reveals how stories were told, retold and repurposed across centuries. This is detective work, certainly, but also a vital act of translation, bringing a distant past into contemporary focus without erasing its texture.

Extending Singapore’s history back to the late 13th century does more than fill gaps. It reframes the colonial narrative, showing Raffles’s arrival not as the beginning of history but as a brief episode within a long evolving sequence. Each newly discovered source from the early modern era invites us to reassess the British role after 1819 and to appreciate the ingenuity and complexity of the societies that came before.

Historical research is like watching a sprawling theatre production. There are moments of sheer brilliance – the Flemish merchant Jacques de Coutre’s vivid accounts, Robert Dudley’s unexpectedly detailed maps – that make you lean forward in your seat. But there are also long stretches of painstaking work: squinting at barely legible manuscripts, untangling centuries of sloppy transcription, or cross-referencing fragmentary evidence. It is rarely dull enough to make you question your life choices, but it is not exactly a steady edge-of-your-seat excitement either.

This work demands patience, attention to detail, proficiency in languages old and older, and above all, a willingness to sit with uncertainty. Yet the rewards are real. Every fragment, map, letter or illustrative sketch breathes life into Singapore before 1819. What once seemed like an empty stage – a long pause between ancient Temasek and Raffles – now fills with movement, commerce, ambitions and the bustle of a space packed with human connections and stories.

Afterthoughts

In the end, the historian is part detective, part translator and part storyteller – filling gaps, reconciling contradictions and illuminating centuries that might otherwise have remained in the dark. Singapore before Raffles was never empty; it was certainly there, sometimes bustling and at times chaotic. Thanks to fresh research, we can finally get a better glimpse as what it truly was: a crossroads of empires, cultures and seas, whose story is far more complex and connected than previously thought.

Looking back to the advice I received in the 1990s, my quest turned out to be anything but futile. The sources were always there – waiting in unexpected archives, private collections and books written in languages long neglected. Earlier historians missed both the sources and the story because they cast their nets too narrowly, asked the wrong questions and expected tidy answers.

As each new discovery surfaces, the story only grows richer, proving that the past, much like the sea, is never still, and that Singapore’s history is deeper, broader and more extraordinary than we ever ventured to think.

Notes

-

Peter Borschberg, “Sources for the Study of Singapore before 1800,” in Reimagining Singapore’s History: Essays on Pre-Colonial Roots and Modern Identity, ed. Matthew Oey (Singapore: Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House, 2025). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5703 REI) ↩

-

Kwa Chong Guan, “Archaeology in the Writing of Singapore’s History,” in Reimagining Singapore’s History: Essays on Pre-Colonial Roots and Modern Identity, ed. Matthew Oey (Singapore: Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House, 2025). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5703 REI) ↩

-

Kwa Chong Guan, Derek Heng and Tan Tai Yong, Singapore, a 700-Year History: From Early Emporium to World City (Singapore: National Archives of Singapore, 2009). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 KWA) ↩

-

Kwa Chong Guan, Derek Heng, Peter Borschberg and Tan Tai Yong, eds., Seven Hundred Years: A History of Singapore (Singapore: National Library Board; Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2019). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 KWA) ↩

-

Isabel Rio Novo, “Luís de Camões in Asia,” BiblioAsia 21, no. 3 (October–December 2025): 44–49. ↩

-

“Singapore in Johann Heinrich Zedler’s Universal-Lexicon,” National Library Online. Article published 2014; Johann Heinrich Zedler, Grosses vollständiges Universal-Lexicon aller Wissenschafften und Künste (Leipzig and Halle: Verlag Heinrich Zedler, 1731–54), https://www.zedler-lexikon.de/. ↩

-

Daniel Defoe, The Life, Adventures, and Piracies of the Famous Captain Singleton (Garfield Heights: Duke Classics, 2012). (From NLB OverDrive) ↩

-

Lee Meiyu, “A Battle Captured in a Map,” BiblioAsia 11, no. 4 (January–March 2016): 52–53. ↩

-

“The 1603 Naval Battle of Changi,” National Library Online. Article published 2013. ↩

-

Robert Dudley, Arcano del mare Tomo I (Europa und Asien) - BSB Cod.icon. 138, 1636, map, Münchener Digitalisierungszentrum, https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/en/view/bsb00094608?page=180 and https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/en/view/bsb00094608?page=181. ↩

-

For the transcribed text of the instructions, see L.J. Matos, “Roteiros e rotas portuguesas do oriente nos séculos XVI e XVII” (doctoral thesis, University of Lisbon, 2016), 333–35. ↩

-

Rob Harris, “Newly Discovered Diary Records Landmark Sighting of Australia in 1687,” Sydney Morning Herald, 27 March 2023, https://www.smh.com.au/world/europe/newly-discovered-diary-records-landmark-sighting-of-australia-in-1687-20230326-p5cvbe.html. ↩

-

Johann Georg Heinrich Hassel, Geographisch-Statistisches Handwörterbuch: Nach den neuesten Quellen und Hülfsmitteln, vol. 2 (Weimar: Im Verlage des geographischen Instituts, 1817), 406, Münchener Digitalisierungszentrum, https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/en/view/bsb10429388?page=1. ↩