Tapping History

I’ve been through Taban Valley at Bukit Timah Nature Reserve many times and never realised until recently how historically important these unprepossessing trees are. To the uninitiated, they look like skinny durian trees with their dark green leaves. A century and a half ago, the Taban Merah (Pafaquium gutta), better known to the world as Gutta Percha, was at the centre of an earth-shaking infocomm revolution as great as the introduction of the Internet.

Discovery

Gutta Percha was traditionally used in this region to fashion handles for tools. However, it was unknown to the West except for a single specimen called ‘mazer wood’ in the collection of naturalist John Tradescant (1608–1652). The Tradescant collection grew to become Oxford’s present Ashmolean Museum.

In 1842, an enterprising Malay man started selling Gutta Percha whips in Singapore. Unfortunately. I have not been able to discover this man’s name anywhere. By 1843, his whips were available in London. However, Gutta Percha whips never became more than a novelty.

At this time, Jose d’Almeida who ran a dispensary at Commercial Square (today’s Raffles Place), went back to Europe for a visit in 1842. He brought along samples of Gutta Percha with him. The samples were presented to the Royal Asiatic Society in London but no real notice was taken of it. This bad fortune in things agricultural extended to his attempt at starting a plantation in Singapore: he tried planting without commercial success many different crops like cotton, coffee and vanilla. However, he was quite successful in the world of trade: after helping two ships sell their cargos, he went on to found a successful trading company, Jose d’Aimeida & Co. Almeida was also knighted by his ruler, the Queen of Portugal, and made Consul General to the Straits Settlements during his trip back home.

It was left to a fellow resident of Singapore, Dr William Morrtgomerie, to successfully introduce Gutta Percha to the world.

Dr William Montgomerie is generally credited to be the first person to notice Gutta Percha in 1822 during his first tour of duty in Singapore (1819 to 1826). However, it was only when he became Senior Surgeon to the Straits Settlement (1829 to 1844) that he investigated the substance more closely. He sent a letter to the Bengal Medical Board in 1843, recommending that Gutta Percha be developed for use in medical instruments. This was followed by samples to the Society of Arts in 1845 for which the Society awarded him a gold medal (the Society of Arts became the Royal Society of Arts only in 1847 when it was given a Royal Charter). More importantly, the Society exhibited the samples, which sparked off much experimentation with the substance.

Among other things Gutta Percha was found to be good for making golf balls, adhesives, and as root canal fillings in dentistry. Even today, if you are unfortunate enough to need root canal treatment, the dentist will probably use Gutta Percha for your root canal filling. Gutta Percha is one of the best substances for ensuring that the cavity is completely filled without leaving any microscopic space where bacteria can resume its attack. The secret behind its varied uses is its changeability- in hot water (around 69 to 65°C, depending on the purity), it becomes plastic and moldable while at room temperature it is firm enough to be made into furniture. Of course you might want to avoid serving a hot meal on a Gutta Percha dining table!

Telegraphy

In 1837, Cooke and Wheatstone filed their patent for a telegraph system in England while Morse filed his patent in the United States the year after. Very quickly, the first long-distance telegraph lines were set up: the first being the famous Washington-Baltimore line. This line was opened on 24 May 1844 when Samuel Morse sent his famous ‘What hath God wrought?’ message across it. The telegraph allowed messages to be sent and received immediately across long distances- it was a communications breakthrough in an era when couriers were the fastest way to send messages. For instance, the front page news of the Singapore Chronicle and Commercial Register on 16 September 1837 announced the death of King William IV and that Victoria would be the next ruler- news three months old! (King William IV died on 20 June 1837).

However, there was one problem preventing a worldwide telegraph net: how do you insulate telegraph cable underwater? On land, air does not conduct electricity, which makes the job easy. However, in water, a reliable airtight casing for the copper wire was needed as water, especially salt water, conducts electricity well. In addition, the material had to be flexible and be able to withstand high pressures and cold temperatures without deteriorating. Materials like lead, wax, tar and caoutchoouc (rubber) were tried without success. Bridges had to be built for cables to be strong across rivers- never mind oceans.

By coincidence, samples of Gutta Percha from Singapore had started arriving in London in 1843. The very next year, various people had seized on it as a possible telegraph cable insulator and experimentation started on how to manufacture such insulated cables. Four years later in Germany, Werner Siemens was the first to develop a working machine press for making a seamless Gutta Percha cable coating. This development enabled telegraph cables to be laid along the floor of the ocean and by the 1870s, telegraph cables circled the globe. Telegraphen-BauanstaFt von Siemens & HaLske, the company founded by Mr Siemens and his brother, also prospered - this was the start of today’s multinational electronics company, Siemens AG.

In 1850, the first undersea cable was laid between England and France, and 1858 saw the first attempt to lay a transatlantic cable - a feat finally achieved in 1866. While Cyrus Field has gone down in history as the man who connected the United States to Europe, it was Gutta Percha from Singapore that made it possible.

The telegraph story would not be complete without mentioning when Singapore became connected to the world. Singapore’s first telegraphic cable connection was to Batavia but the first line broke after the first message. it was only on 31 December 1870 that the British Australian Telegraph Company finished laying a telegraph line from Madras to Singapore. A few days later, on 6 January 1871, an advertisement appeared in the newspapers announcing the opening of the telegraph lines between Singapore, Penang, Java and Madras. This allowed telegraph messages to be sent to Europe and even to the Americas! The cost was not cheap though: a twenty-word message to London cost 24 Straits dollars and to New York, the princely sum of 53.60 Straits dollars!

Commercial Harvesting

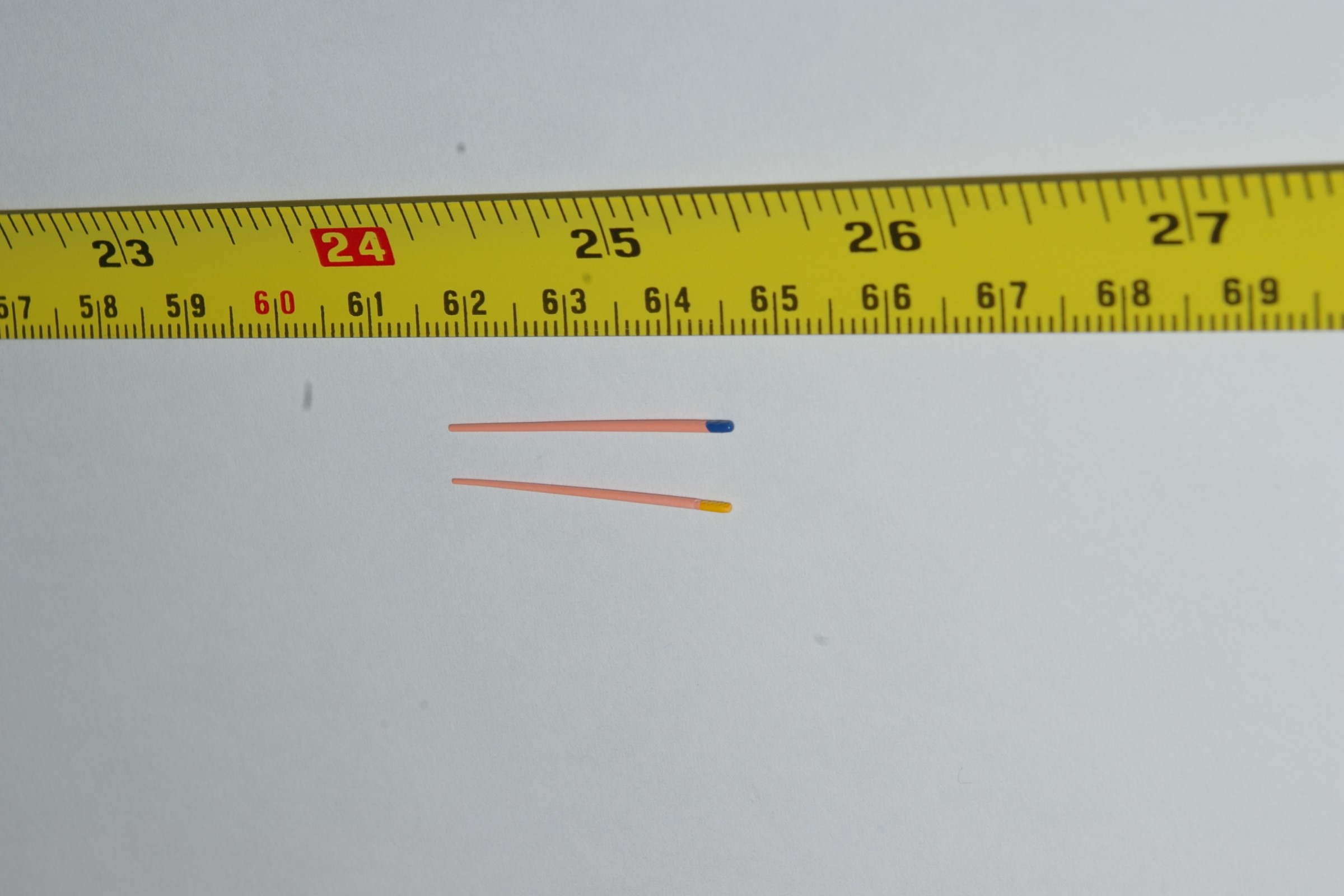

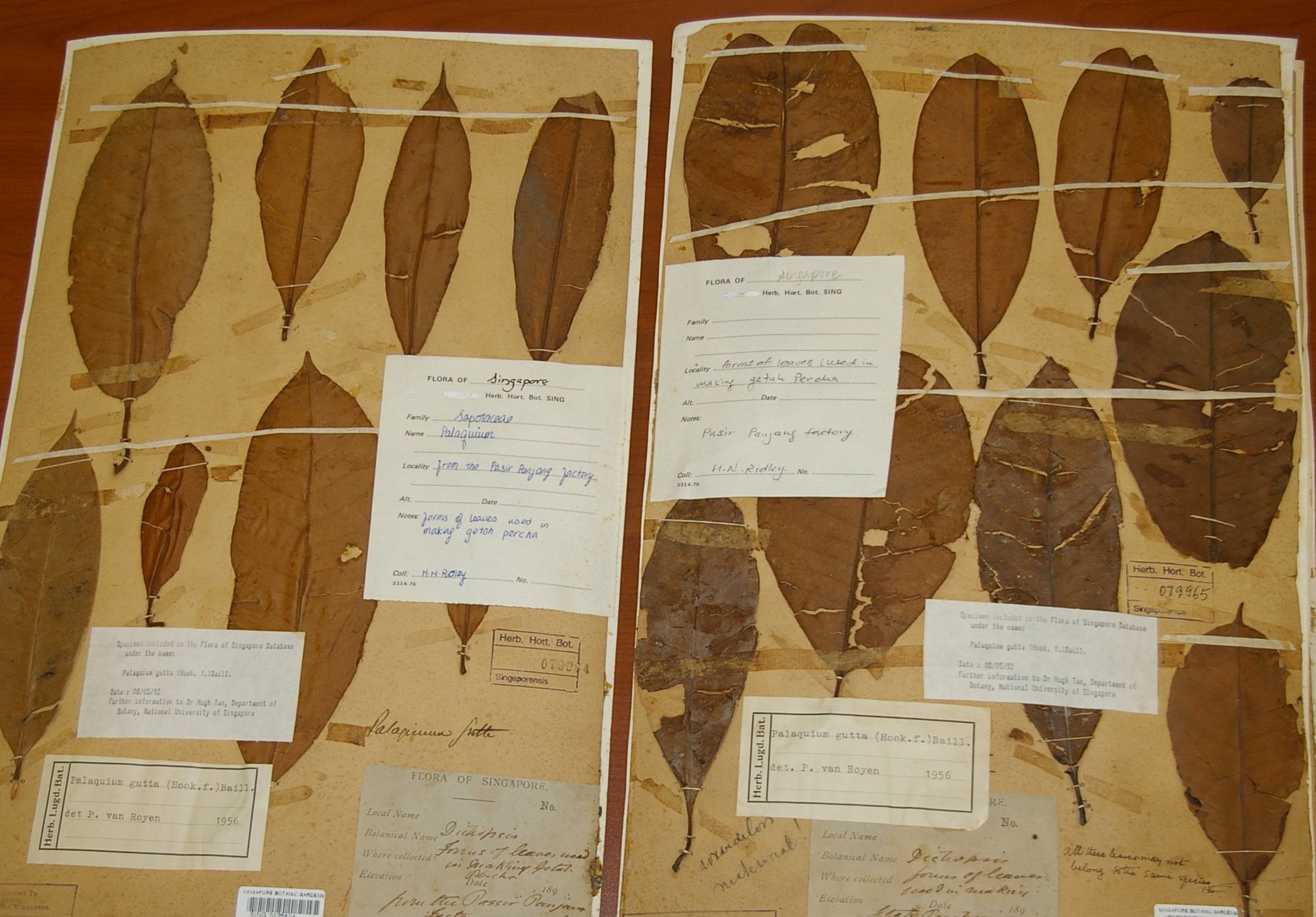

Unlike rubber, Taban tree sap does not flow freely through the length of the trunk. It also hardens quickly on exposure to air. This means that making cuts in the trunk only collects a limited amount of sap. The initial method of collection was therefore to cut down the tree and make cuts along the trunk in order to milk out as much sap as possible. Early attempts at tapping only resulted in poor harvests and a reportedly high rate of diseased trees. The only 19th century advance in harvesting techniques was the invention of a process to extract sap from the leaves in order to maximise the sap harvested from each tree harvested. A leaf collecting system with leaf processing factories was established in several locations in Malaysia and Indonesia. However, it was soon found that collectors would cut down the young saplings in order to collect the leaves and leaf harvesting was discontinued.

It was only in the early 20th century that a successful system of tapping the Taban was devised: diagonal cuts were made at regular intervals up the length of the trunk using a ladder. The sap would then seep out and coagulate along the length of the cuts. The tapper would then roll the coagulated sap up. Being re-exposed, the cuts would bleed afresh and the process would be repeated until the available sap was exhausted. Besides being labour intensive, the tree also had to be given time to recover from the massive injuries suffered. This recovery period was said to be at least two years.

The tree was not common in the rainforest but grew in scattered clumps. The result of the huge demand for Gutta Percha was the quick demise of Taban in Singapore. Just two years after Montgomerie introduced Gutta Percha to Europe, all of Singapore’s big Taban trees had been felled and Thomas Oxley (1847) estimated that the 412 tons of Gutta Percha exported to Europe between 1845 and 1846 had resulted in 69,000 Taban trees being cut down.

There is even a short article on “Rediscovery of the Gutta Percha Tree at Singapore” published in the Kew Gardens’ Bulletin of Miscellaneous Information (1891). Because Taban Merah grows quickly when there is plenty of light, it is a suitable plantation crop. The only difficulty is that the young plants initially need to be shaded - only more mature plants benefit from direct sunlight. The Dutch were quick to export saplings from Singapore for starting plantations in Java and by the turn of the century had sizable plantations there.

Personalities

In Singapore, the first person to plant Taban Merah was Thomas Oxley at his home on Oxley Rise. Then in the 1880s, specimens were planted at the Botanic Gardens and subsequently at Bukit Timah.

Another person intimately involved with Gutta Percha was Temenggong Ibrahim. He had inherited the title of Temenggong but not any source of income: the British East India Company and the Dutch government had usurped taxation of trade in the region. Local rulers trying to levy charges on passing ships quickly found themselves being hunted down as pirates. In addition, the Temenggong had to assist Orang Laut coming in from the Riaus to seek his protection: British anti-piracy patrols there were attacking all perahus (Malay boats). The Temenggong moved to get involved in British anti-piracy efforts and also started opening Johor to agriculture.

He met with success on both fronts: he became seen as an invaluable ally to Governor Bonham’s anti-piracy campaign, leased out Johor land to Chinese pepper and gambier farmers, and became a major Gutta Percha exporter. William Read’s 1901 book Play and Politics, records that a local merchant informed the Temenggong of Gutta Percha’s potential. Perhaps this local merchant was Ker, a neighbour of his. Indeed, Ker, Rawson & Company sent the Termenggong’s first shipment of Gutta Percha to Europe. The Temenggong quickly dedared a monopoly on Gutta Percha collection in Johor and set about organising a collection system in Johor, employing labourers to harvest the trees. By reinventing himself as a major agricultural player, the Temenggong quickly prospered in both wealth and status.

Description

In 1847, Logan published the first issue of his journal: The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia. To most people, it is known simply as ‘Logan’s Journal’. In it, Thomas Oxley, Montgomerie’s successor as Senior Surgeon to the Straits Settlements, described Gutta Percha, the history of its discovery by Europeans, and the uses he had found for it.

Oxley said that Palaquium gutta quite resembled the Durio (durian) genus. I found that to be quite true - at a distance, the reddish-brown underside of the Taban leaves and solid green upper surface make it resemble a durian tree. Not surprisingly, one Malay name for the tree is Ekur Daun Durian (the Ekur tree with leaves like a durian). Flowers grow in groups of four with six petals on each flower. You can see a beautiful illustration of the leaves and flowers from volume three of Kohler’s Medizinal-Pflanzen. This book is available online at the Missouri Botanical Garden Library’s rarebook server: https://www.mobot.org/mobot/archives/. The tree could reportedly reach 36 metres in height and three metres in girth but with harvesting, trees became much smaller. I believe the girth of the ones in Taban Valley are only a metre. You can spot these old trees with their tap wounds if you take a stroll around the Taban Loop trail In Bukit Timah Nature Reserve. While it is characteristic of the Gutta Percha and its relatives in the Sapotaceae family to bleed a milky white sap when cut, only certain trees in the genera Palaquium and Payena produce enough good quality Gutta sap to be usable. The quality is directly related to the isoprene and caoutchine content in the sap. Among the trees in - these two general, Palaquium gutta, known locally as Taban Merah, produces the best Gutta (getah is the Malay word for rubber). Other Gutta-produchg species cornmercially harvested include Palaquium obovatum (Taban Puteh), Palaquium maingayi (Getah Ketapang or Getah Percha Burong), Palaquium oxleyanum, and Payena leeril (Getah Sundik). Ironically, the tree that is locally called Getah Perca (Payena maingayi), produces a sap that is worthless because it does not harden.

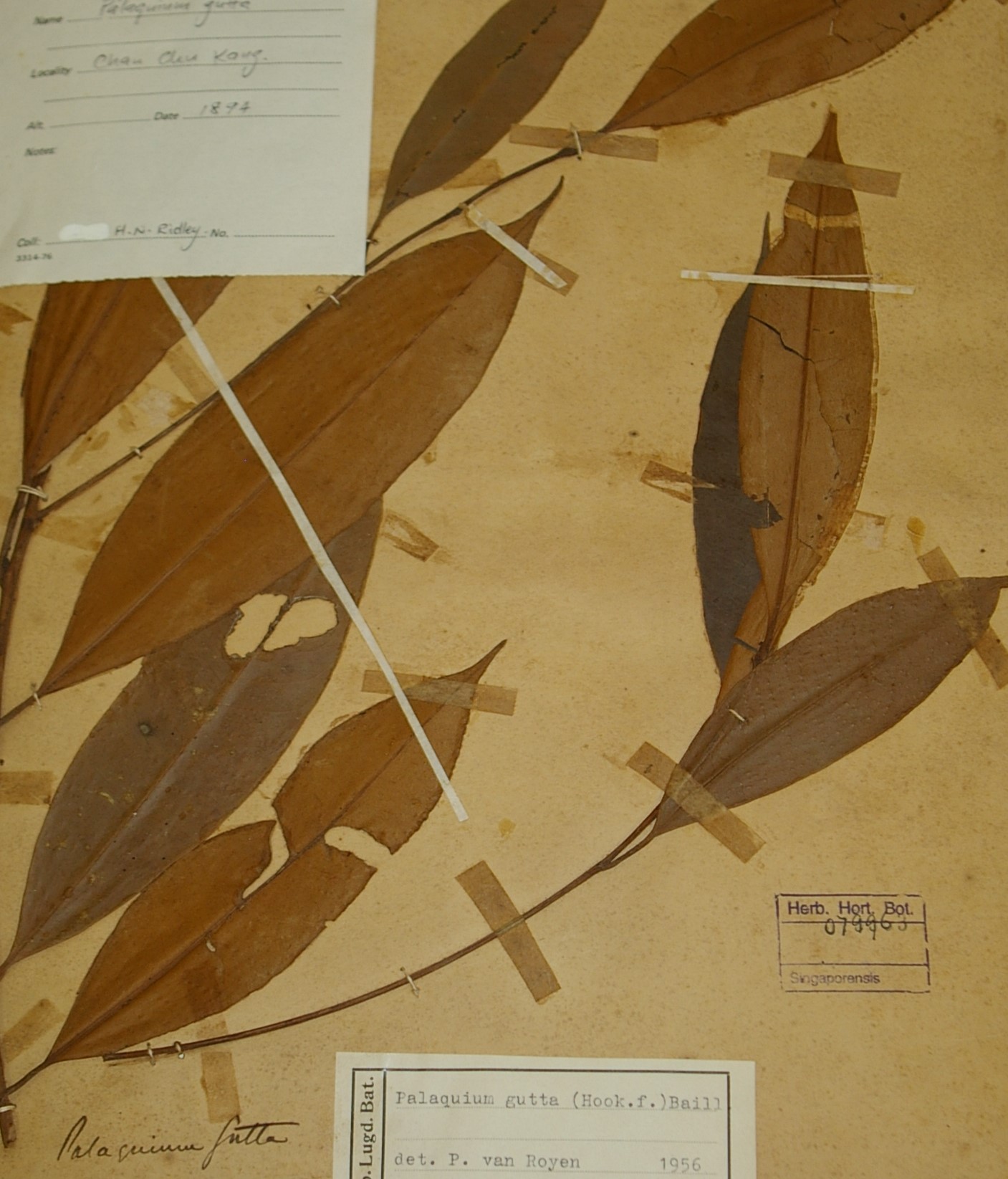

I would like to thank Serena Lee of the Botanic Gardens Herbarium for allowing me acess to photograph Ridley’s specimens and Eunice Low and Shawn Lum for reading my draft and suggesting improvements to the article.

Senior Reference Librarian

Lee Kong Chian Reference Library

National Library

REFERENCES

Carl A. Trocki, Prince of Pirates: The Temenggongs and the Development of Johor and Singapore, 1784–1885 (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1979). (Call no. RSING 959.5142 TRO)

Charles Burton Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1984). (Call no. RSING 959.57 BUC). This book can also be found in the Singapore Heritage Collection of NLB’s eCollection at https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/home

Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Gutta-percha”, accessed 26 April 2007, https://www.britannica.com/technology/gutta-percha.

F. E. Kohler, Kohler’s Medizinal-Pflanzen in Naturgetreuen Abbildungen MIT Kurz Erlauterndem Texte: Atlas Zur Pharmacopoea Germanica (Gera-Untermhaus, Fr. Eugen Kohler, [1883–1914])

“Gutta-percha” in Pamphlets: Malayan Series, British Empire Exhibition London 1924 (Singapore: Fraser & Neave, 1923). (Call no. RRARE 959.5 BRI; microfilm N12450)

I. H. Burkill, A Dictionary of the Economic Products of the Malay Peninsula, vol. 2. (London: Published on behalf of the Governments of the Straits Settlements and Federated Malay states by the Crown Agents for the Colonies, 1935). (Call no. RCLOS 634.909595 BUR)

“Opening of the Lines to Java, Penang and Madras,” Singapore Daily Times, 6 January 1871. (Microfilm NL1977)

“Rediscovery of Gutta Percha Tree at Singapore (Dichopsis Gutta, Benth),” Bulletin of Miscellaneous Information (Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew) 1891, no. 57 (1891): 230–1. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

T. Oxley, “Gutta Percha,” The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia 1 (1847): 22–29. (Call no. RRARE 950.05 JOU; microfilm NL1889)

W. H. M. Read, Play and Politics, Recollections of Malaya By An Old Resident (London: Wells Gardner, Darton & Co., 1901). (From BookSG; call no. RRARE 959.503 REA; microfilm NL14075)