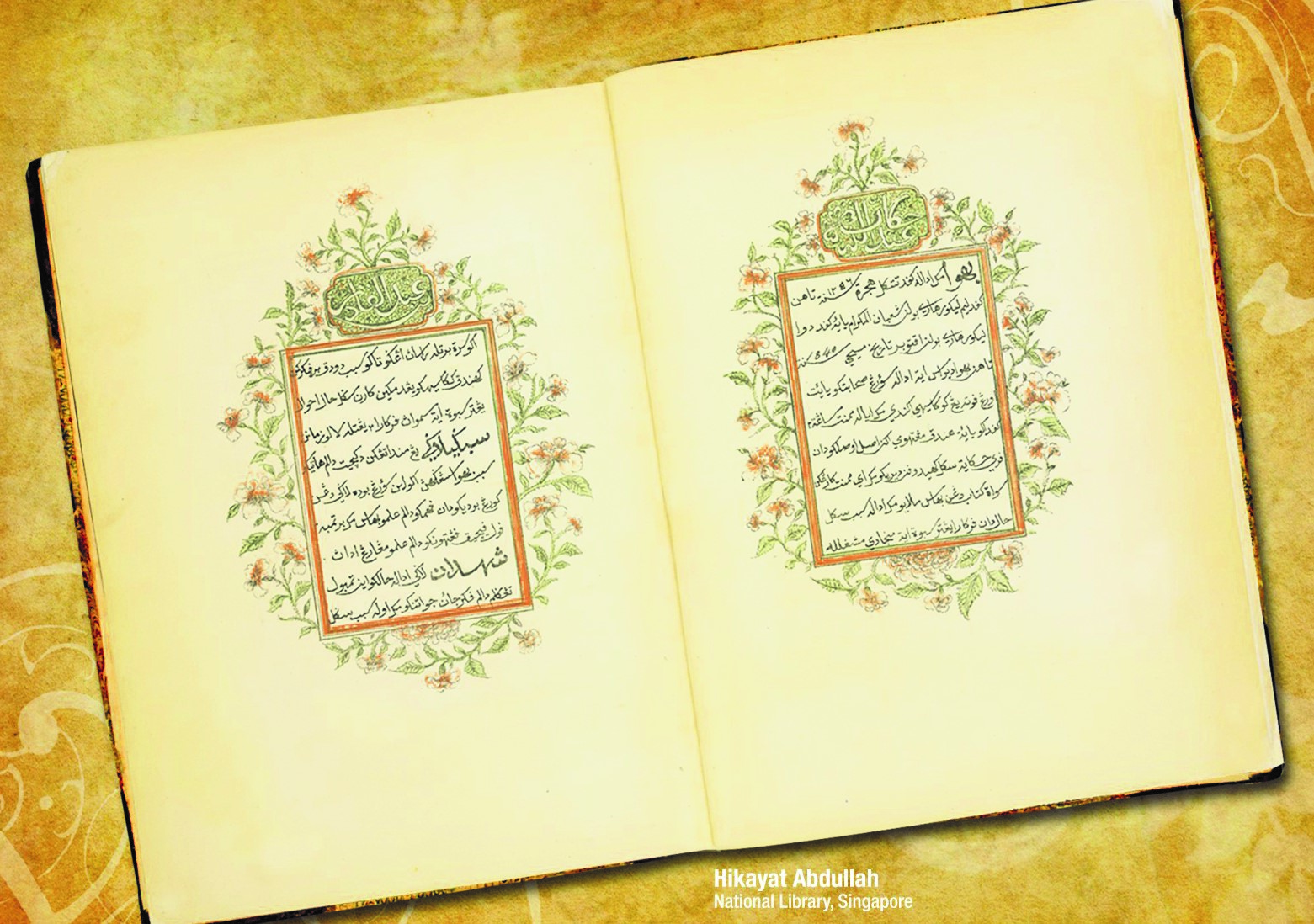

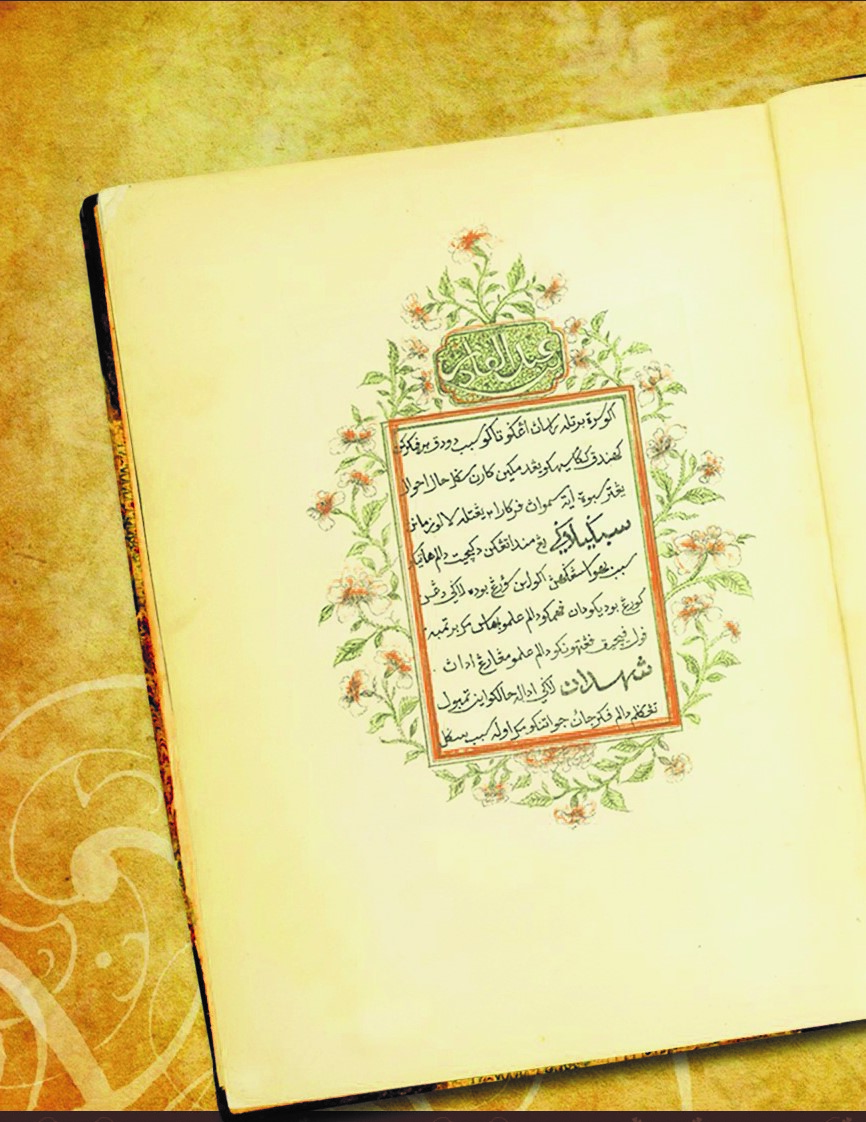

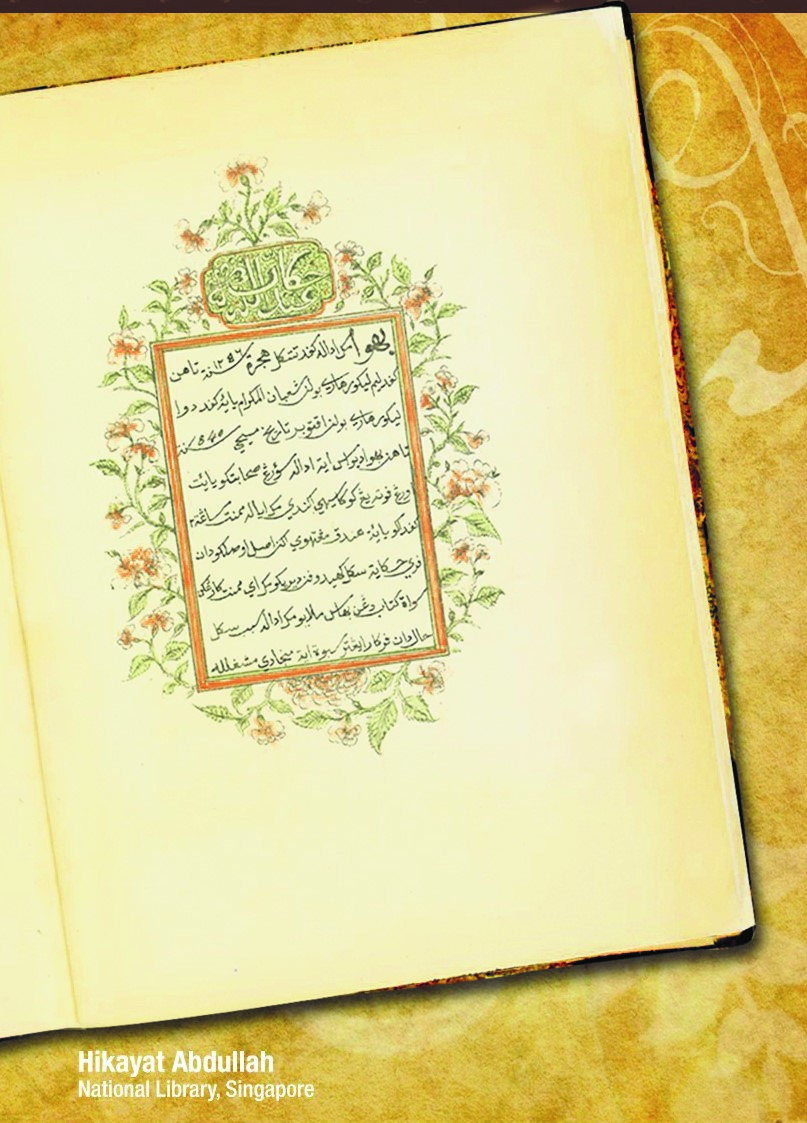

Excerpts from Hikayat Abdullah

Hikayat Abdullah (The Story of Abdullah) by Munshi Abdullah Abdul Kadir provides glimpses of life in early Singapore. Abdullah arrived in Singapore from Melaka about four months after Stamford Raffles established a trading post on the island in February 1819.

In our last two issues, we introduced the autobiography of Munshi Abdullah Abdul Kadir which was written in Jawi between 1840 and 1843 and published in 1849. The author was the interpreter and scribe to the founder of modern Singapore, Sir Stamford Raffles.

In this issue, we continue to highlight stories from the Hikayat Abdullah (The Story of Abdullah). The Hikayat Abdullah provides glimpses of life in early Singapore. Abdullah arrived in Singapore from Malacca about four months after Singapore became a British trading port in 1819.

From Abdullah’s accounts, Singapore was certainly not a place for the faint-hearted. It was used as a port by the pirates to plunder ships and boats sailing near Singapore.

Syahadan, adapun pada masa itu, jangankan manusia

hendak lalu-lalang di laut Singapura itu, jin syaitan pun takut,

sebab di situlah bilik tempat perompak tidur, atau barang

di mana pun ia merompak kapal atau keci atau perahu,

dibawanyalah ke Singapura. Di situlah tempat ia membahagi

harta dan membunuh orangnya atau berbunuh-bunuhan

sesama sendirinya, sebab merebut harta itu, adanya.1

At that time, the sea surrounding Singapore was far from being navigated freely by men, for along the shores were the sleeping-huts of the pirates. Whenever they plundered a ship or a ketch or a cargo-boat, they brought it into Singapore to share the spoils. They also slaughtered the crew or fought to death among themselves to secure their gains.2

Lawlessness was rife in Singapore, despite the presence of the British. There were frequent incidents of houses catching fire, robberies in broad daylight, people getting stabbed, houses broken into and property stolen.3 The situation was almost out of control as the law enforcers themselves became victims.

Bermula pada tiap-tiap hari hari waktu itu tiada berkeputusan orang mati dibunuh sepanjang jalan Kampung Gelam itu. Maka ada juga mata-mata polis menjaga sana-sini, akan tetapi berapa-berapa banyak mata-mata itu dibunuh orang sehari.4

Every day without fail, murders took place along the road to Kampong Gelam. There were policemen on duty but they themselves were often murdered.5

The chapter “Darihal Kernel Farquhar Kena Tikam” (Colonel Farquhar Stabbed) recounted Farquhar being stabbed by Sayid Jasin over the latter’s dispute with Pengeran Sharif Omar. Farquhar had ruled in favour of Pengeran Sharif Omar. Another chapter “Darihal T’ien Ti Hui dalam Negeri Singapura” (Thian Tai Huey Society in Singapore) told the story of a powerful Chinese secret society with thousands of members, and the majority lived a life of robbery, piracy and murder. Singapore was seemingly a dangerous place to be.

The animals and insects of Singapore also added more colour to the adventurous life in Singapore. According to Abdullah, there were few animals in Singapore but there were thousands of rats all over and some were almost as large as cats. Many people were attacked by the rats when walking out at night. The rat situation grew so bad that Farquhar had to offer a reward for the killing of a rat. This initiative turned out to be very effective:

Maka pada tiap-tiap kali berkerumunlah orang membawa bangkai tikus ke rumah Tuan Farquhar. Pada seorang lima enam puluh dan yang ada enam tujuh ekor. Maka pada mula-mulanya hampir-hampir beribu tikus dibawa orang pada sepagi, sampai bertimbunlah bangkai itu, dibayar oleh Tuan Farquhar seperti perjanjiannya itu. Maka adalah enam tujuh hari demikianlah. Dilihatnya terlalu banyak juga. Maka ditawarnya seekor lima duit. Maka itu pun dibawa orang juga, beribu-ribu, lalu disuruhnya gali tanah dalam-dalam, ditanamkan segala bangkai-bangkai. Maka dengan hal yang demikian reda[h]lah sedikit tikus itu, sampai dibawa orang pada sehari sepuluh dua puluh sahaja. Lalu berhentilah peperangan dan pergaduhan tikus itu dalam Singapura, sekalianya habislah lesap sekali, adanya.6

Every day, crowds of people brought the carcasses to Colonel Farquhar’s place. Some had 50 or 60, while others only six or seven. At first, the rats brought in every morning were counted almost in thousands, and Colonel Farquhar paid out according to his promise. After six or seven days a multitude of rats were still to be seen, and he promised five duit for each rat caught. They were still brought in in thousands and Colonel Farquhar ordered a very deep trench to be dug and the carcasses to be buried. Soon, the numbers began to dwindle, until people were bringing in only ten or twenty a day. Finally, the uproar and the campaign against the rats in Singapore came to an end, and the infestation completely subsided.7

There was a similar problem with centipedes infesting people’s homes, biting the people and causing them much annoyance. Farquhar took the same approach of offering a reward for the killing of a centipede. The campaign against the centipedes was equally successful.

There was also an incident of Farquhar’s dog being attacked and eaten by a crocodile, while walking along Sungai Rocah (Rochor River). The crocodile was subsequently captured and killed.

Setelah sudah, maka buaya itu pun terkepunglah lalu ditikam orang sampai mati, ada tiga depa panjangnya. Maka baharulah diketahui orang ada buaya di Singapura. Maka oleh Tuan Farquhar disuruhnya ambl bangkai buaya itu digantungkannya di pohon jawi-jawi yang di tepi Sungai Beras Basah itu, adanya.8

The crocodile was hemmed in by the obstruction and speared to death. It was 15 feet long. That was the first time that people realised there were crocodiles in Singapore. Colonel Farquhar ordered the crocodile’s carcass to be taken, and hung on a fig tree by the side of the Beras Bas ah River.9

Librarian

Lee Kong Chian Reference Library

National Library

REFERENCES

A.H. Hill, The Hikayat Abdullah: The Autobiography of Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, 1797–1854 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1969). (Call no. RSING 959.51032 ABD)

Hassan Ahmad, ed., Hikayat Abdullah (Kuala Lumpur: Yayasan Karyawan, 2004). (Call no. RSING 899.2809 ABD)

NOTES

-

Hassan Ahmad, ed., Hikayat Abdullah (Kuala Lumpur: Yayasan Karyawan, 2004), 145. (Call no. RSING 899.2809 ABD) ↩

-

A.H. Hill, The Hikayat Abdullah: The Autobiography of Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, 1797–1854 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1969), 144. (Call no. RSING 959.51032 ABD) ↩

-

Hill, Autobiography of Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, 159. ↩

-

Ahmad, Hikayat Abdullah, 164. ↩

-

Hill, Autobiography of Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, 160. ↩

-

Ahmad, Hikayat Abdullah, 148–9. ↩

-

Hill, Autobiography of Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, 147. ↩

-

Ahmad, Hikayat Abdullah, 173. ↩

-

Hill, Autobiography of Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, 168. ↩