Destined to be an Entrepreneur and a Philanthropist to be Remembered

Lee Kong Chian built a business empire that stretched beyond the boundaries of Malaya into Thailand, Indonesia, and even to the United States and the United Kingdom. Today, his name and reputation live on, as his business and philanthropy continue to thrive.

In 1903, when he was a mere 10-year old, Lee left his home in Furong (Nan’an County in Fujian Province) to join his father in Singapore, soon after his mother passed away. It was not unusual in the early 1900s for many young Hokkiens to travel overseas in search of a better life, as the infertile and hilly lands of Southern Fujian offered little employment. Unlike many who could only find jobs as coolies, Lee began life in Singapore with his first taste of formal education, through the financial support of a family friend.1 The kindness of this friend would serve as an inspiration for young Lee, who in his adulthood would contribute millions of dollars to the education of the Chinese, both overseas and in his motherland. Lee’s first school was the Anglo-Tamil School at Serangoon Road, and it was here that Lee acquired his proficiency in the English and Tamil languages. In the afternoons, Lee continued his Chinese education at the Chongzheng School. This practice of attending both English and Chinese schools in a day continued through to his secondary education, where he studied at St. Joseph’s Institution and Tao Nan School. In this manner, he was introduced to both Western and Eastern concepts.

In 1904, a number of Chinese officials were sent to Southeast Asia to promote education in China. The scholarly Lee was awarded a prestigious Manchu scholarship to study at Chi Nan School in Nanjing, and returned to China in 1908. There, he excelled in Mathematics, Physics and Chemistry, and applied himself to his studies so diligently that he gained top honours.

Despite tumultuous political changes, Lee continued his studies at Ching Hwa High School in Beijing in 1911 and thereafter pursued a degree in engineering at the College of Mining and Communication in Tang Shan. The only time Lee expressed a political stance was when he cut off his queue in protest against the Qing rulers, although this was likely through coercion by the older students,2 as he reportedly donned a false queue in class to hide his affiliations. He also joined the Tong Meng Hui society (which later became the Kuomintang) during his student years. However, civil unrest soon consumed the country, and by 1912, when China became a republic, Lee’s Manchurian scholarship came abruptly to an end.

Determined to complete his studies, Lee took up an American correspondence course in civil engineering upon his return to Singapore. At the same time, he was employed by the Survey Department as an assistant, and attended the Department’s Special Survey classes. Lee also juggled several other jobs, including teaching at Tao Nan School and Chung Cheng High School, as well as translating English news reports for the Chinese daily, Lat Pau.

Turning Point

While working at the Survey Department, Lee came across a ruling in the General Orders of the civil service that indicated only men of “pure European descent” would be recognised for the top positions in government. This disappointing discovery influenced Lee’s decision to leave the civil service and to work for a friend, Cheng Hee Chuan, instead. Even so, he still sought to further his studies in engineering in Hong Kong.3 However, a chance encounter with a renowned Chinese business leader would soon change his direction in life.

An anecdotal story has it that Tan Kah Kee and Lee Kong Chian met one rainy evening while both were dining at a streetside eatery. Lee loaned Tan an umbrella, and was to collect it back at Tan’s rubber factory. The following day, Lee visited the factory just when Tan was receiving his first American clients. Requiring assistance in interpreting English documents, Tan was impressed by Lee’s competence in translating the materials, and thereafter solicited Cheng Hee Chuan to allow Lee to work for Tan instead.4 But though Tan headed one of the most established Chinese companies in Malaya, Lee was supposedly reluctant to accept Tan’s offer of employment, as it meant he would have to forgo his plans to study in Hong Kong.5

At the time of Lee’s employment at Tan’s Khiam Aik Company in 1916, Tan was expanding and diversifying his business.6 He had established his business in rubber plantations in Malaya with his first seedlings in 1906,7 and was ready to move beyond rubber manufacturing to engage in rubber trading as well. Chinese rubber manufacturers, however, were obliged to sell their goods through agents to their larger foreign counterparts (such as Sime Darby, the Harrison Group, Boustead and Guthrie) for export to the European market.8 Tan was keen to break this stranglehold and sought to export goods directly to the West. At that time, American companies were also seeking to trade directly with the local manufacturers so as to bypass the high rubber prices controlled by the British rubber houses.9 A trusted English interpreter would have been essential to Tan’s business expansion, so Lee’s entry into Khiam Aik proved fortuitous.

Rubber King During the Great Depression

Tan took advantage of his own strengths and the weaknesses of his Western rivals and clients, and had diversified into rice export, pineapple canning and shipping and was working to ship rubber directly to the Americans. Through these transformative years at Khiam Aik, Lee learnt the intricacies of the rubber industry and the art of trading. He proved to be such a valuable asset to the company that, within four years of his employment, Lee was given the hand of Tan’s eldest daughter in marriage. At 17, the educated Tan Ai Lay was about to sit for her final exams but had to forgo this for her marriage to Lee.

Many interpret this union as an attempt by Tan to keep Lee from establishing his own business and thus becoming a rival.10 Indeed, it would be seven years before Lee could set up his own company – a small rubber smoke-house in Muar, Johore – in 1927, and this only with the approval of his father-in-law and Lee’s promise that his business would not compete with Tan’s.11

October 1929 spelt the start of an economic darkness that would soon engulf industries in the West and subsequently destroy many in the rubber business in Malaya. However, Lee was able to ride through these dark times through strategic alliances and careful purchases. He helped his friend Lim Nee Soon settle a large debt by persuading the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank for a settlement. In gratitude, Lim offered to lease his rubber factory in Nee Soon village to Lee on condition that Lim’s son retained a share in the business. Lee named the factory Lam Aik (Lee Rubber Company), an independent entity from his father-in-law’s company, thus marking the start of his own rise in business.

The Great Depression served as an opportunity for Lee to expand his business, by buying off struggling rival companies at rock-bottom prices. By adopting a conservative approach of buying and immediately selling rubber, rather than stockpiling, Lee had also avoided huge losses when the price of rubber drastically spiralled downwards.12 By 1932, Lee’s company was only one of about two or three prominent rubber companies owned by the Chinese that were left standing during the Great Depression. The lessons learnt throughout that period reinforced the value of controlled purchase and reselling of rubber, a business practice that saw Lee Rubber through the ups and downs of the volatile rubber trade.

Lee practised both the Chinese methods of building businesses as well as modern techniques of operations with great success. Through the Chinese style of guanxi, he built partnerships with former rubber magnates and expanded his business by establishing Hok Tong Company in Indonesia (1932), Siam Pakthai in Thailand (1934),13 and the South Asia Corporation in New York (1938) to handle the export of rubber to America. Factories were also strategically located in parts of Malaysia, such as Muar, Penang, Seremban, Klang, and Kuala Lumpur, with branches in Palembang and Medan in Sumatra. In fact, before World War II, Lee’s business had already diversified, to include Lee Pineapple and Lee Biscuits. His leadership in the Chinese community was also seen in the various posts he held. He was Chairman of the Chinese High School (1934), President of the Chinese Rubber Dealers’ Association (1937), and President of the Chinese Chamber of Commerce (1939). He continued Tan Kah Kee’s practice of disbursing low salaries but rewarding with extravagant bonuses every profitable year. In this way, Lee ensured a low cost for personnel but also maintained staff loyalty through the large bonuses.

Lee was an educated entrepreneur, comfortable with both Chinese and English cultures. He chose to place qualified and reliable managers in key decision-making positions, rather than resorting to the nepotism often encountered in traditional Chinese conglomerates. He also applied modern accounting methods to keep track of expenditure and profits.

Lee became a major player in the banking sector when his patron and clansman, Yap Geok Tui, who was then the Managing Director of the Chinese Commercial Bank, placed him as one of the bank’s Board of Directors. Lee urged the local Chinese banks - the Oversea-Chinese Bank and the Ho Hong Bank – to merge with the Chinese Commercial Bank, and helped to work out an arrangement that would benefit all parties. The merger was a success, and a new amalgamated entity, the Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation (OCBC), was formed, with Yap as Chairman and Lee as its Vice-Chairman. In 1938, Lee became OCBC Bank’s Chairman, retaining this position for 27 years until his retirement in 1964.

Destruction and Restoration

The invasion and fall of Singapore in 1942 was completely unexpected. Lee had left for a Rubber Study Group Meeting in Washington D.C. with his wife and three of his children, just weeks before the Japanese invasion.

Even though Lee remained in the United States during the war years, he remained involved in issues concerning Southeast Asia, and gave lectures at Columbia University.

Lee returned to Singapore at the end of 1945, keen to resurrect his business. With a generous loan from the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank, Lee rebuilt his factories in time for the boom in the rubber industry brought about by the Korean War of the 1950s. Thus, Lee Rubber flourished and established itself as the world’s largest rubber exporter in the post-war era.14 Lee continued to diversify his business, and entered the sawmill, coconut oil mill, printing, property, and trading industries. Lee was also generous to his employees. In 1950, he introduced management shares,15 and in 1951, he built homes for his own employees and encouraged home ownership through a salary deduction scheme.16 Furthermore, he remained ahead of his time, by instituting the latest methods and equipment. Lee Rubber was the first company to apply computerised systems, beginning with IBM machines in 195417 and computers in 1960, primarily to manage accounts, track market information as well as the group’s performance.18

Thus, Lee meticulously built his empire on a firm foundation of modern management and accounting, employee care and loyalty, and strategic investments and trade. In that same vein, Lee would practise the art of philanthropy.

Philanthropy and Social Impact

Lee’s contributions to charity began much later in life. He had witnessed his own father-in-law’s passion for the community, through the establishment of schools in Singapore and in his hometown in China. However, Tan Kah Kee had supported these charitable causes at the cost of his own business, so Lee was careful to ensure that his charity work would not jeopardise his business in the same way. Thus, it was only after he had retired in 1954, having groomed his sons to take over his business affairs, did Lee take an active role in community and charitable causes.

Meanwhile, in March 1952, the Lee Foundation was established with a funding of $3.5 million from Lee’s own business, for the purpose of supporting charity projects. By the mid-1950s, he had donated monies to schools like Kuo Chuan Girls’, Nan Chiau Girls’ High, Chinese High, Methodist Girls’, St Margaret’s, Singapore Chinese Girls’, the University of Malaya and Nanyang University. He also donated to community institutions such as the Hokkien Huay Kuan Building, the Chinese Swimming Club and the National Library. Yet for all his contributions, Lee specifically requested that his name not be used in any of the institutions. Instead, many of the institutions took on the name of his father – Lee Kuo Chuan – during the period he donated. Today, the Lee Foundation continues to contribute to the establishment of institutions. The Lee Kong Chian Reference Library (National Library Board, 2005), the Lee Kong Chian School of Business (Singapore Management University, 2000) and the Lee Kong Chian Art Museum (National University of Singapore) are just a few of such initiatives.

Lee’s community work extended beyond disbursing money to charities. In 1954, he flew back from London at the urgent request of the principal of Chinese High to quell a student protest. More than 2,000 students had camped out for more than 22 days, calling for an exemption from military service to the British government. Lee personally spoke to the students and liaised with an initially defiant Governor Nicoll19 to resolve the stand off.

Lee stood up for Malayan rights even though he was often politically misunderstood. To the British government he was perceived as a pro-communist, while to the Chinese he was too westernised, and to the Malayans he was too Chinese-oriented. Evidence of his fight for a Malayan identity can be seen in his call for free membership and the development of a Southeast Asian collection when he contributed to the building of a public library. Prior to that, the Raffles Library had only been a subscription library which required a fee from its members, and much of its collection was focused on the lifestyles and cultures of the West.

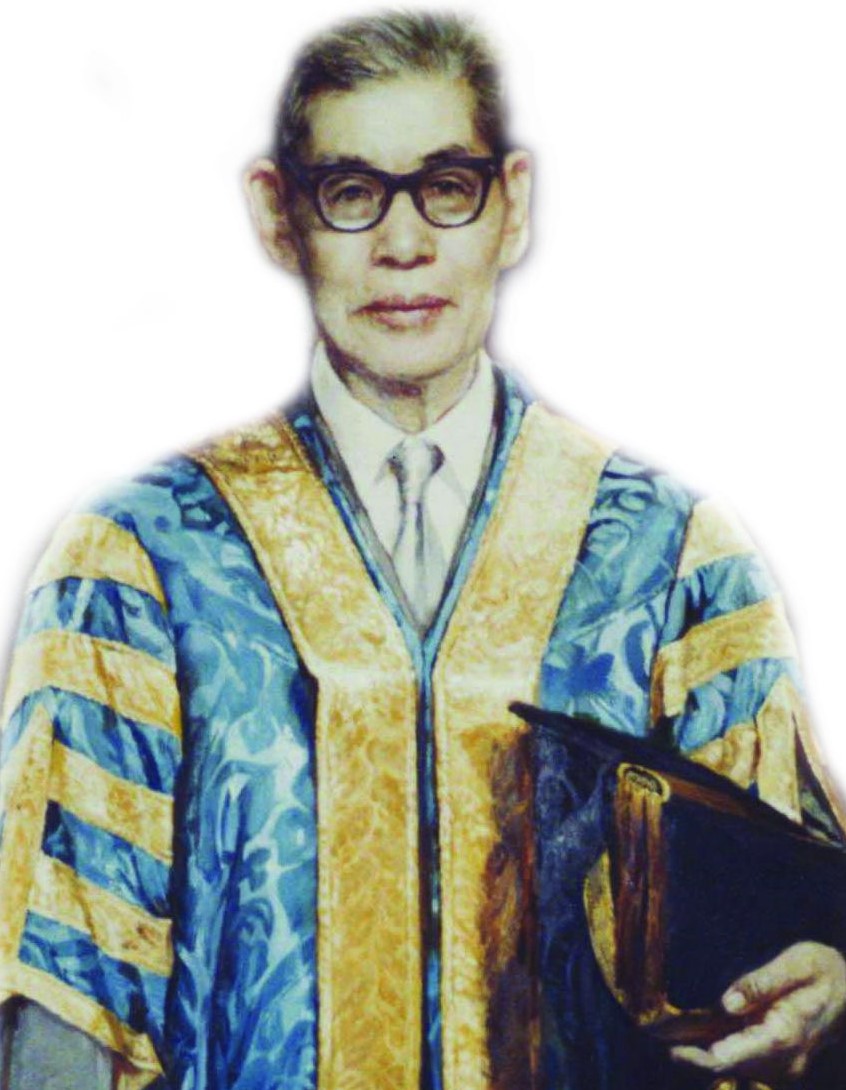

Lee was also the first Asian Chancellor of the University of Singapore, the highest post in the nation’s most esteemed institution of learning, a position previously reserved for only the colonial head of state.

The Private Lee

Despite his high standing in society, Lee maintained a humble and unpretentious lifestyle. Before his marriage, he slept in simple quarters, including the office of his first employer Cheng Hee Chuan, and at the teachers’ quarters of the Tao Nan School. Even when he finally acquired a large house at Chancery Lane after marriage, he reportedly used 1-cent nickel spoons.20 Tan Ee Leong, his school friend and colleague, recounted an encounter he once had with Lee while riding the tram. Seats in the tram ranged from first class to third class, and as Tan Ee Leong was just a student at that time, he could only afford the second class seats. One day, he chanced upon Lee Kong Chian (then already the Manager of Tan Kah Kee’s company) sitting in the third class. “I felt so embarrassed, because he was already working, (and) I was still a student”, Tan recalled.21

Unlike traditional Chinese entrepreneurs, Lee had a strong foundation in education before he became a businessman. He was gifted in mathematics, and was also well-read in the Western classics. He was a keen student of languages (he also understood Tamil and Malay), and continued with his language studies even after he retired, when he picked up French and learnt German.22

Lee died quietly on 2 June in 1967 after suffering from liver cancer for two years. Yet even with his passing, his legacy lives on. Indeed, Lee Kong Chian’s life is a testament to a quote he made during his inaugural speech as Chancellor of the University of Singapore:

“Barang siapa yang ingin memetek padi yang bagus, hendak-lah menaborkan beneh yang bagus pula” - “Whoever wants to harvest good rice, must also plant good seeds.”23

Senior Librarian

Lee Kong Chian Reference Library

National Library

REFERENCES

Archives & Oral History Department, Singapore, Pioneers of Singapore: A Catalogue of Oral History Interviews (Singapore: Archives & Oral History Department, 1984). (Call no. RSING 016.9595700992 SIN)

Hong Liu and Sin-Kiong Wong, Singapore Chinese Society in Transition: Business, Politics, and Socio-Economic Change, 1945–1965 (New York: Peter Lang, 2004). (Call no. RSING 959.5704 LIU)

Lee Kong Chian, “Convocation,” University of Singapore Gazette 1, no. 1 (1962): 4–5 (1), https://www.nus.edu.sg/docs/default-source/corporate-files/about/community/chancellors/lee-kong-chian.pdf.

Lee Seng Gee, oral history interview by Lim How Seng, 29 October 1980, transcript and MP3 audio, 27:44, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000040), 14.

Low Yit Leong, “Panoply of Pineapple Lee,” Singapore Chronicles (Hong Kong: Illustrated Magazine Pub., 1995), 120–25. (Call no. RSING 959.57 SIN)

M. R. Gasmier, “Reliving Lee Kong Chian,” Alumnus no. 17 (March 1994): 5–10. (Call no. RSING 378.5957 A)

“Obituary-Tan Sri Dr Lee Kong Chian,” Dongnanya yanjiu 东南亚研究 [Journal of Southeast Asian Researches] 3 (1967): 1–8. (Call no. Chinese RCLOS 959 KUZ)

Tan Ban Huat, “Rubber Tycoon Who Never Forgot the Poor,” Straits Times, 10 November 1987, 4. (From NewspaperSG)

Tan Ee Leong, oral history interview by Lim How Seng, 29 October 1980, transcript and MP3 audio, 27:44, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000003), 131.

Yen Ching Hwang, “Tan Kah Kee and the Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurship,” 亚洲文化 [Asian Culture] 22 (June 1998): 1–3. (Call no. Chinese RSING 950.05 AC)

Yen Ching Hwang, “The Confucian Revival Movement in Singapore and Malaya 1877–1912,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 7, no. 1 (March 1976): 33–57. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Zheng B., Li Guangqian zhuan [The story of Lee Kong Chian] (Beijing: Zhongguo Huaqiao Chubanshe, 1997)

NOTES

-

Lee Seng Gee, oral history interview by Lim How Seng, 28 August 1980, transcript and MP3 audio, 27:37, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000040), 3. ↩

-

Yen Ching Hwang, “The Confucian Revival Movement in Singapore and Malaya 1877–1912,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 7, no. 1 (March 1976): 47. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Tan Ee Leong, oral history interview by Lim How Seng, 29 May 1981, transcript and MP3 audio, 27:32, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000003), 119. ↩

-

Zheng B., Li Guangqian zhuan [The story of Lee Kong Chian] (Beijing: Zhongguo Huaqiao Chubanshe, 1997), 31. ↩

-

Zheng, Li Guangqian zhuan, 29–30. ↩

-

Yen Ching Hwang, “Tan Kah Kee and the Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurship,” 亚洲文化 [Asian Culture] 22 (June 1998): 2. (Call no. Chinese RSING 950.05 AC) ↩

-

Archives & Oral History Department, Singapore, Pioneers of Singapore: A Catalogue of Oral History Interviews (Singapore: Archives & Oral History Department, 1984), 36. (Call no. RSING 016.9595700992 SIN) ↩

-

Hong Liu and Wong Sin-Kiong, Singapore Chinese Society in Transition: Business, Politics, and Socio-Economic Change, 1945–1965 (New York: Peter Lang, 2004), 206. (Call no. RSING 959.5704 LIU) ↩

-

Hong and Wong, Singapore Chinese Society in Transition, 207. ↩

-

Zheng, Li Guangqian zhuan, 31. ↩

-

Tan Ban Huat, “Rubber Tycoon Who Never Forgot the Poor,” Straits Times, 10 November 1987, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lee Seng Gee, oral history interview by Lim How Seng, 28 August 1980, transcript and MP3 audio, 27:41, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000040), 18. ↩

-

Hong and Wong, Singapore Chinese Society in Transition, 209. ↩

-

Low Yit Leong, “Panoply of Pineapple Lee,” Singapore Chronicles (Hong Kong: Illustrated Magazine Pub., 1995), 122. (Call no. RSING 959.57 SIN) ↩

-

Hong and Wong, Singapore Chinese Society in Transition, 213. ↩

-

M. R. Gasmier, “Reliving Lee Kong Chian,” Alumnus no. 17 (March 1994): 7–8. (Call no. RSING 378.5957 A) ↩

-

Obituary-Tan Sri Dr Lee Kong Chian,” Dongnanya yanjiu 东南亚研究 [Journal of Southeast Asian Researches] 3 (1967): 4. (Call no. Chinese RCLOS 959 KUZ) ↩

-

Tan Ee Leong, oral history interview by Lim How Seng, 29 May 1981, transcript and MP3 audio, 27:44, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000003), 131. ↩