Singapore, an Emerging Centre of 19th Century Malay School Book Printing and Publishing

Historical events suggest that Singapore emerged as a centre of Malay school book production in the 19th century. Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow Lim Peng Han traces the four phases of its development.

Identifying the Four Phases of Development

Historical events suggest that Singapore emerged as a centre of Malay school book production in the 19th century through four phases of development.

Firstly, it was not accidental that the printing began in Singapore since its founding in 1819, but a conscious policy was likely to have been initiated by its founder, Stamford Raffles, and Dr William Morrison, co-founder of the Anglo-Chinese College in Malacca (1818–43).

Introduction: British Presence in the Malay Peninsula

In 1786, the East India Company took possession of Penang. From 1786 to 1805, the island was a dependency of Bengal, and in 1805, Penang created the 4th Indian Presidency, with a large staff of officials (Mills, 1925, pp. 18–30). In that same year, Raffles became the secretary of the Penang Presidency at the age of 24. He learnt the Malay language and soon replaced the resident and interpreter with his letter-writing abilities in the Malay language (Cross, 1921, pp. 33–34).

Raffles and the Manuscript Tradition

In 1810, Raffles was appointed Agent to the Governor-General of the Malay States by Governor-General Minto in Calcutta. Subsequently, Raffles set up a base in Malacca in December the same year to prepare for the invasion of Java in 1811 (Bastin, 1969, pp. 9–10). During this period, Raffles employed Ibrahim, Tambi Ahmad bin Nina Merikan, Munshi Abdullah, his uncle Ismail Lebai and his younger brother Mohammed as copyists of Malay “letters and texts” (Hill, 1955, p. 72).

Founding of Singapore in 1819: Singapore Institution and the First Printing Presses

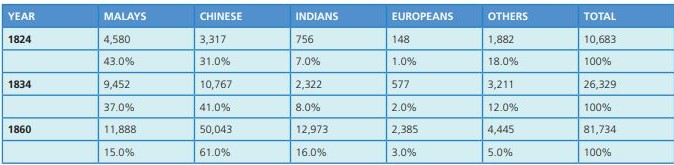

After Raffles founded Singapore in 1819, immigrants from Malacca, China, India and the neighbouring islands of the Netherlands East Indies flocked to the island (Saw, 1969, pp. 37–38). In 1824, immigrant Malays made up about 43 percent of the total population of Singapore. By 1860, this figure dropped to about 15 per cent, as shown in Table 1. Chinese immigrants formed the largest racial group, at about 61 percent in 1901. Malays were the largest minority race, compared with the Indians and Europeans.

Raffles’ Education Policies for the New Settlement

Education was recognised by Raffles as one of the first needs of his new settlement (Neilson, n.d., p. 1). In 1819, Raffles wrote the first education policy for the island:

1 To educate the sons of higher order of natives and others.

2 To afford the means of instruction in the native languages to such of the Company’s servants and others as may desire it.

3 To collect the scattered literature and traditions of the country, with whatever may illustrate their laws and customs and to publish and circulate in a correct form the most important of these, with such other works as may be calculated to raise the character of the institution and to be useful or instructive to the people (Raffles, 1991, p. 33).

Reverend Robert Morrison, the distinguished Chinese scholar and first Protestant missionary to China, then read a paper suggesting that the London Missionary Society (LMS)-sponsored Anglo-Chinese College (1815–43) (Harrison, 1979, pp. xi–xii) in Malacca be removed to Singapore and amalgamated with the proposed Singapore Institution (Philips, 1908, p. 269). The modified proposed Singapore Institution was to consist of three departments:

I. A scientific department for the common advantage of the several College that may be established.

II. A literary and moral department for the Chinese, which the Anglo-Chinese College affords.

III. A literary and moral department for the Siamese, Malay, & c., which will be provided for by the Malayan College (Raffles, 1991, p. 75).

Raffles’ accounts of his educational schemes – one dated 1819, on the establishment of the Malay College at Singapore (Raffles, 1991, pp. 23–38), and one dated 1823, describing the foundation and policy of the Singapore Institution (Raffles, 1991, pp. 77–86) – were intended for the whole region, the Malay Peninsula, Singapore and the Indonesian archipelago. His educational schemes therefore were designed to include not only the principal peoples of the Malay Peninsula, but also the Javanese, the Bugis, the Siamese and other people from the surrounding islands (Hough, 1933, p. 166).

The second minute, dated 1823 at the meeting of the trustees, gave an account of the foundation and policy of the Singapore Institution. A proposed plan of the building drawn by Lieutenant Jackson was approved, and plans were made to purchase printing presses with “English, Malayan, and Siamese founts of types”, “and also to employ, on the account of the Institution”, a printer. LMS missionary Samuel Milton was appointed to take charge of the presses and superintend the printing. John Argyle Maxwell, Secretary to the Institution, was requested to take charge of the Library and Museum of the Institution, and to act as the Librarian (Raffles, 1991, p. 83).

As a collector of Malay manuscripts, Raffles would have known that he would need to translate European texts into Malay, and to convert Malay manuscripts into books for his proposed Singapore Institution. He also knew the importance of having printing presses, and would have known that the LMS missionaries brought the printing presses to Malacca to print the first Malay books as well as Chinese books (Ibrahim Ismail, 1982, pp. 193–195).

First Phase: First Printing in Malay in 1822

Rev. Samuel Milton went to Singapore in October 1819 to establish a mission, and permission was given by Major Farquhar to set up a station upon his arrival (Milne, 1820, p. 289). In 1821, Rev. Claudius Henry Thomsen quit the LMS Malacca station to establish a Malay mission in Singapore (Medhurst ,1838, p. 315). Thomsen and Munshi Abdullah “reached Singapore between the second quarter of 1821 and the middle of May, 1822” (Gibson-Hill, 1955, p. 195). Thomsen took with him a portable press and settled in Singapore (O’Sullivan, 1984, pp. 65–66). The first printing in Malay occurred in 1822 when Abdullah translated into Malay a Raffles proclamation making gambling and the opium farms illegal. The evidence is not conclusive but this was printed by the Mission Press and distributed around October 1822. The Mission Press, as it was designated, catered to the commercial and government needs of the infant settlement for eight years without a competitor (Byrd, 1970, pp. 13–14).

Second Phase: Missionary Printing and Malay Classes at the Singapore Institution, 1817–46

The LMS and Malay Classes at the Singapore Institution, 1817–46

It was the LMS which first brought printing in Malay to the Straits Settlements by establishing stations in Malacca (1815–43), Singapore (1819–46) and Penang (1819–44). The first printing in 1822 in Singapore was in Malay, (Byrd, 1970, p. 14) when LMS missionary Thomsen brought with him a press from Malacca the same year (O’Sullivan, 1984, pp. 65–66). In 1826, the colonies of Penang, Malacca and Singapore were amalgamated to form the Straits Settlements (Jarman, 1998, p. v). In 1832, the seat of Government was transferred from Penang to Singapore (McKerron, 1948, p. 126)

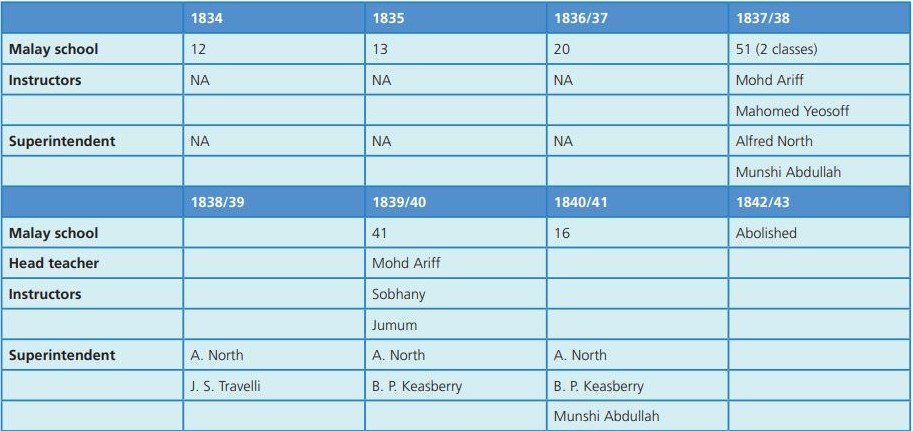

According to the annual reports of the Singapore Institution (1834–37) and the Singapore Institution Free School (1838–43), Malay religious tracts and books from the LMS stations in Penang, Singapore and Malacca were used by the Malay classes of the Singapore Institution.

The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) and Malay classes at the Singapore Institution, 1834–42

In 1834, the ABCFM established a station in Singapore after transferring their Chinese xylographic printing from Canton. Alfred North, a printer by training, arrived in 1836 and became a special student of Munshi Abdullah. Only two tracts in Malay were printed (Croakley, 1998, p. 26). North collaborated with Munshi Abdullah to publish two Malay books, Kesah Pelayaran Abdullah (1838) (Gallop, 1990, p. 97) and Sejarah Melayu (1840/41) (Ibrahim Ismail, 1986, pp. 17–19). These books were used as school books in the Malay classes at the Singapore Institution in 1852 (Singapore Institution Free School, 1853, p. 21), and were the first school books published by a local author. Two years later, Munshi Abdullah passed away in Mecca (Raimy Che-Ross, 2000, p. 182). After the Opium War in 1842, many Chinese ports were opened and the LMS and the ABCFM missionaries closed their stations and left for China (Graaf, 1969, p. 37).

The history of the spread of Malay printing in Southeast Asia in the first half of the 19th century is very much the history of Protestant activity in the region (Gallop, 1990, p. 92). In Singapore, the ABCFM also contributed to the spread of Malay book printing and publishing.

Third Phase: Keasberry, the First Official Translator and Printer of Malay School Books, 1847–75

In 1846, Benjamin Peach Keasberry was ordered to close the work in Singapore, but he refused to leave. On 2 April 1846, he wrote to the LMS in London, telling them that he could not “reconcile himself to the thought of this station being given” (Haines, 1962, p. 226). He was convinced that his work lay among the Malay-speaking population, although he was left without resources. He was allowed to use the mission press and the mission property at Bras Basah Road. Keasberry supported himself and his work by printing and teaching (Bachin, 1972, p. 12).

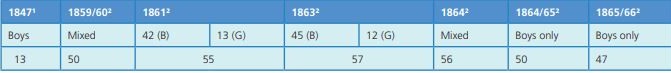

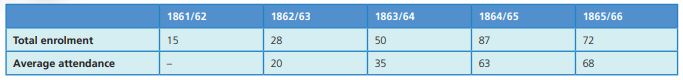

In 1856, the Temmenggong of Johor and the East India Company (EIC) each contributed an annual sum of $1,500 to set up two Malay schools, one at Telok Blangah and the other at Kampong Glam, and to support Keasberry’s Malay mission school. In addition, part of the money was used to translate Malay manuscripts and publish them “to instruct Malay youth” (Jarman, 1998, p. 88). Keasberry was the first person to be officially appointed to translate and publish Malay school books for the colony.

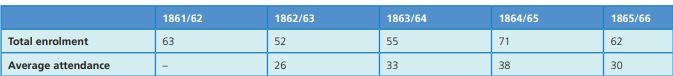

Note: According to the Annual Report on the Administration of the Straits Settlements, 1859–64, there were mixed enrolments of boys and girls. Buckley, 1965, p. 322; Jarman, 1998, pp. 218, 366, 370, 522, 640, 744.

Keasberry’s death brought an end to any extensive work in the Malay language on the peninsula for 20 years (Hunt, 1989, p. 41). In addition, the translation and production of Malay school books was interrupted, since his printing presses were sold to John Fraser and D.C. Neave in 1879 (Makepeace, 1908, p. 265). Fraser and Neave went on to publish directories, guides and company reports in English (Md Sidin Ahmad Ishak, 1992, p. 81).

Fourth Phase: Straits Settlements Under the Colonial Office and Expansion of Malay Government Schools: The Education Department’s Government Malay Press, 1885–99

In 1867, the Straits Settlements were transferred from the control of the Indian Government to that of the Secretary of State for the Colonies in London. In 1870, the first governor, Harry Ord, appointed a select committee “to enquire into the State of Education in the Colony”. Upon the recommendations of the Committee, the first Inspector of Schools was appointed in 1872 to greatly extend and improve Malay vernacular schools (Wong & Gwee, 1980, p. 11).

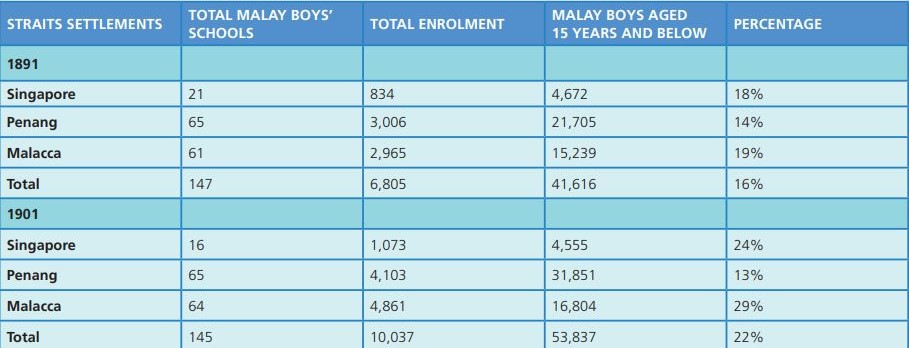

In 1891, 16 percent of Malay boys aged 15 and below in the Straits Settlements were enrolled in Malay vernacular boys’ schools. By 1901, 22 percent of Malay boys in the same age group went to Malay vernacular boys’ schools in the Straits Settlements (as shown in Table 6).

Establishment and Growth of Government Malay Vernacular Girls’ Schools, 1884–1900

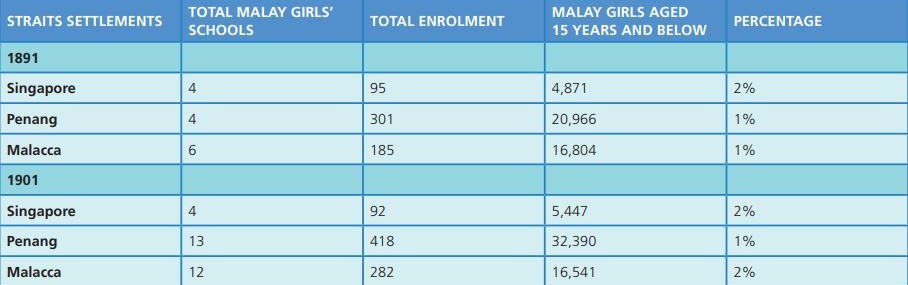

Malay girls’ schools were only founded in 1884, as there were difficulties to overcome in the establishment of such schools (Hill, 1885, p. 150). In 1901, no more than 2 percent of Malay girls were enrolled in Malay vernacular girls’ schools in the Straits Settlements (as shown in Table 7). The rapid expansion of Malay vernacular schools in the 19th century was mainly confined to boys’ schools.

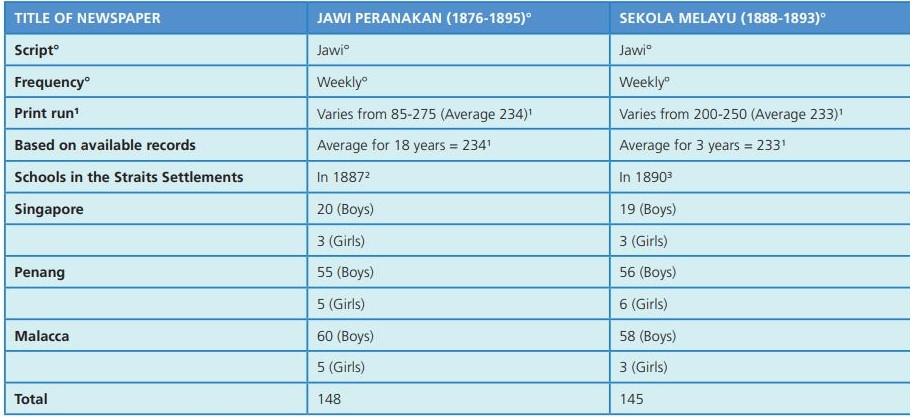

It is likely that the shortage of Malay school books resulted in the government’s purchase of two Malay vernacular newspapers, the Jawi Peranakan (1876) and Sekolah Melayu (1895), to be used as reading materials in the government Malay schools (Jacobson, 1889, p. 216).

It was not until 1885 that Malay school book printing and publishing resumed with the setting up of the Government Malay Press. This was normally regarded as part of the Government Printing Office, and the books printed on this press bore the Government Press imprint (Proudfoot, 1993, p. 592). In 1888, the firm Kelly & Walsh was appointed “to sell all books required in the schools” (Penny, 1888, p. 189). By 1893, Kelly & Walsh supplied books not only to the growing number of pupils and schools in the Straits Settlements, but also to those in the Malay States, Johor, Muar, Borneo and Sarawak (Hill, 1894, p. 322).

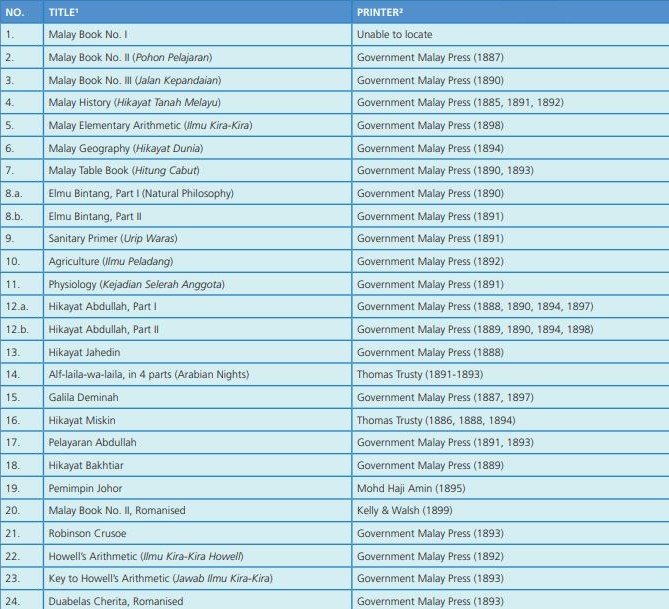

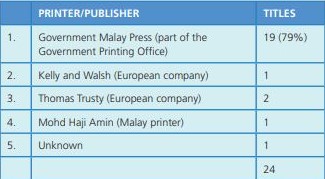

In 1894, out of 24 Malay school books printed in Singapore, 19, or 73 percent, were produced by the Government Malay Press (as shown in Tables 9 and 10).

It was thus through these series of historical events and collaborations that Singapore emerged as a centre of 19th-century Malay school book production and distribution in the Straits Settlements.

The author wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Dr Annabel Teh Gallop, Head, South and Southeast Asia section, The British Library in reviewing the paper.

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow

National Library

REFERENCES

A.H. Hill, “An Annotated Translation of the Hikayat Abdullah,” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 28, no. 3 (June 1955), 1–345. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Abdullah Abdul Kadir and Annabel Teh Gallop, “Cerita Kapal ASAP,” trans. Annabel Teh Gallop, Indonesian Circle no. 47–48 (1989), 3–18.

Annabel Teh Gallop, “Early Malay Printing: An Introduction to the British Library Collection,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 63, no. 1 (1990), 85–124. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

B. Nunn, “Some Account of Our Governors and Civil Service,” in One Hundred Years of Singapore, ed. Walter Makepeace, Gilbert E. Brooke and Roland St. J. Braddell (London: John Murray, 1921), 69–148. (Call no. RCLOS 959.51 MAK)

Brian Harrison, Waiting for China: The Anglo-Chinese College at Malacca, 1818–1843, and Early Nineteenth-Century Missions (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1979). (Call no. RSING 207.595141 HAR)

Brian Harrison, Holding the Fort: Malacca Under Two Flags (Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1986). (Call no. RSING 959.5141 HAR)

C. Bazell, “Education in Singapore,” in One Hundred Years of Singapore, ed. Walter Makepeace, Gilbert E. Brooke and Roland St. J. Braddell, vol. 1 (London: John Murray, 1921), 427–76. (Call no. RCLOS 959.51 MAK)

C.E. Wurtzburg and W. Robinson, “The Baptist Mission Press at Bencoolen,” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 23, no. 3 (August 1950): 136–42. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

C.M. Philips. (1908). “Raffles Institution, Singapore,” in Twentieth Century Impressions of Malaya: Its People, Commerce, Industries, and Resources, ed. Arnold Wright and H.A. Cartwright (London: Lloyd’s Greater Britain Publishing Company Ltd., 1908), 269–72. (Call no. RCLOS 959.3 TWE-[SEA])

C.M. Turnbull, “Melaka Under British Colonial Rule,” in Melaka: The Transformation of a Malay Capital, c. 1400–1980, vol. 1, ed. Kernial Singh Sandhu and Paul Wheatley (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1983), 242–96. (Call no. RSEA 959.5141 MEL)

C. Silvester Horne, The Story of the L.M.S (London: London Missionary Society, 1895). (Call no. RCLOS 266 HOR)

Cecil K. Byrd, Early Printing in the Straits Settlements, 1806–1858 (Singapore: National Library, 1970). (Call no. RSING 686.2095957 BYR)

Charles Burton Buckley, An Anecdotal History of the Old Times in Singapore: From the Foundation of the Settlement Under the Honourable East India Company on February 6th, 1819 to the Transfer of the Colonial Office as Part of the Colonial Possessions of the Crown on April 1, vols. 1 and 2 (Singapore: Fraser & Neave, 1902). (From BookSG; call no. RRARE 959.57 BUC; microfilm NL269)

Demetrius Charles Boulger, The Life of Sir Stamford Raffles (Amsterdam: The Pepin Press, 1999). (Call no. RSING 959.57021092 BOU)

Ding Choo Ming, “Access to Malay Manuscripts,” Bijdragen tot de Taal-,Landen Volkenke 143, no. 4 (1987), 425–51. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

E.C. Hill, Annual Report of Education in the Straits Settlements for the Year 1884 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1885)

E.C. Hill, Annual Report of Education in the Straits Settlements for the Year 1890 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1891)

Ernest Chew, “The Foundation of a British Settlement,” in A History of Singapore, ed. Ernest C.T. Chew and Edwin Lee (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1991), 36–40. (Call no. RSING 959.57 HIS)

F.G. Penny, Annual Report of Education in the Straits Settlements for the Year 1887 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1888)

F.K. Bachin, “A Short Life of Benjamin Peach Keasberry,” in The Presbyterian Church in Singapore and Malaysia, 90th Anniversary of the Church and 70th Anniversary of the Synod Commemoration Volume (Singapore: Presbyterian Church in Singapore and Malaysia, 1971), 11–13. (Call no. RSING 285.1595 PRE)

Francis H.K. Wong and Gwee Yee Hean, Official Reports in Education: Straits Settlements and the Federated Malay States (Singapore: Pan Pacific Book Distributors Ltd., 1980). (Call no. RSING 370.95957 WON)

G.A. Gibson-Hill, “The Date of Munshi Abdullah’s First Visit to Singapore,” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 28, no.1 (March 1955), 191–95. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

G.G. Hough, “Notes on the Educational Policy of Sir Stamford Raffles,” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 11, no. 2 (117) (December 1933), 166–70. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

H.J. de Graaf, Indonesia (Amsterdam: Vangendt & Co., 1969). (Call no. RCLOS 686.209598 GRA)

H. Marriott, “The Peoples of Singapore,” in One Hundred Years of Singapore, ed. Walter Makepeace, Gilbert E. Brooke and Roland St. J. Braddell (London: John Murray, 1921), 341–76. (Call no. RCLOS 959.51 MAK)

Ian Proudfoot, The Print Threshold in Malaysia (Clayton: The Centre of Southeast Asian Studies, 1994). (Call no. RSEA 070.509595 PRO)

Ian Proudfoot, Early Malay Printed Books: A Provisional Account of Materials Published in the Singapore-Malaysia Area Up to 1920, Noting Holdings in Major Public Collections (Kuala Lumpur: Academy of Malay Studies and The Library, University of Malaya, 1993). (Call no. RSING 015.5957 PRO)

Ibrahim Ismail, “Missionary Printing in Malacca, 1815–1843,” Libri, 32, no. 3 (1982), 117– 206.

Ibrahim Ismail, “The Printing of Munshi Abdullah’s Edition of the Sejarah Melayu in Singapore,” Kekal Abadi 5, no. 3 (1986), 13–19. (Call no. RCLOS 027.7595 UMPKA)

Isemonger, E.E. et al., Report of the Committee Appointed to Enquire into the System of Vernacular Education in the Colony (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1894)

Ismail Hussein, The Study of Traditional Malay Literature: With a Selected Bibliography (Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, 1974). (Call no. RSEA 899.23007 ISM)

James Coakley, “Printing Offices of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, 1817–1900: A Synopsis,” Harvard Library Bulletin 9, no. 1 (Spring 1998), 5–34.

John Bastin, Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles: With an Account of the Raffles-Minto Manuscript Collection Presented to the India Office Library on 17 July 1969 by the Malaysia-Singapore Commercial Association (Liverpool: National Museum, 1969). (Call no. RCLOS 959.570210924 RAF.B)

John Bastin, “The Missing Edition of C. H. Thomsen and Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir’s English and Malay Dictionary,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 56, no. 1 (244) (1983), 10–11. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

John Barrie Nielson, A History of Raffles Institution (Singapore: [Raffles Institution], 1927–29). (Call no. RCLOS 373.5957 NEI)

John Crawfurd, Journal of an Embassy From the Governor-General of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China: Exhibiting a View of the Actual State of Those Kingdoms, 2nd ed. (London: H. Colburn and R. Bentley, 1830). (From BookSG; call no. RRARE 959.7 CRA; microfilm NL11335)

John Feather, A History of British Publishing, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, 2006). (Call no. R 070.50941 FEA)

Joseph Harry Haines, “A History of Protestant Missions in Malaya During the Nineteenth Century, 1815–1881,” (bachelor’s dissertation, Princeton Theological Seminary, 1963). (From ProQuest via NLB’s eResources website)

Kartini Yayit, “Vanishing Landscapes: Malay Kampongs in Singapore,” (Bachelor’s theses, University of Singapore, 1987)

Kevin Y. L. Tan, ed., “A Short Legal and Constitutional History of Singapore,” in The Singapore Legal System (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1999), 26–66. (Call no. RSING 349.5957 SIN)

L.A. Mills and C.O. Blagden, “British Malaya 1824–1867,” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 3, no. 2 (November 1925): 1–198. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Leona O’Sullivan, “The London Missionary Society: A Written Record of Missionaries and Printing Presses in the Straits Settlements, 1815–1847,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 57, no. 2 (247) (1984): 61–99. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Lim Lena U Wen, A Preliminary Survey of a Retrospective National Bibliography for Malaya and Singapore Up to 1941 ([n.p.]: University of London, 1965). (Call no. RCLOS q010.28 LIM)

M. Cross, “Stamford Raffles, The Man,” in One Hundred Years of Singapore, ed. Walter Makepeace, Gilbert E. Brooke and Roland St. J. Braddell (London: John Murray, 1921), 32–68. (Call no. RCLOS 959.51 MAK)

Maurice Collis, Raffles (London: Faber and Faber, 1966). (Call no. RCLOS 959.570210924 RAF.C)

Md. Sidin Ahmad Ishak, “Malay Book Publishing and Printing in Malaya and Singapore, 1807–1949” (PhD diss., Stirling University, 1992)

P.A.B. McKerron, Report on Singapore for the Year 1947 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1948)

P.J. Begpie, The Malayan Peninsula: Embracing Its History, Manners and Customs of the Inhabitants, Politics, Natural History &C. From Its Earliest Records (Madras: Vepery Mission Press, 1834). (From BookSG; call no. RRARE 959.5 BEG; microfilm NL5827)

P. Lim Pui Huen, Marion Southerwood and Katherine Hui, Singapore, Malaysian and Brunei Newspapers: An International Union List (Singapore: Southeast Asian Studies, 1992). (Call no. RSING 016.0795957 LIM)

Philip Lawson, The East India Company: A History (London: Longman, 1993). (Call no. RSING 382.0942050903)

R.G. Jacobson, Annual Report of Education in the Straits Settlements for the Year 1888 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1889)

Raimy Che Ross, “Munshi Abdullah’s Voyage to Mecca: A Preliminary Introduction and Annotated Translation,” Indonesia and the Malay World 28, no. 81 (July 2000):173–213, 182.

Robert A. Hunt, “The History of the Translation of the Bible into Bahasa Malaysia,” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 62, no. 1 (256) (1989), 35–56. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Robert L. Jarman, ed., Annual Reports of the Straits Settlements 1868–1883, vol. 2 (London: Archive Editions Limited, 1998). (Call no. RSING 959.51 STR)

Saw Swee-Hock, “Population Trends in Singapore, 1819–1967,” Journal of Southeast Asian History 10, no. 1 (March 1969): 36–49. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Singapore Institution Free School, The First Report of the Singapore Institution Free School 1834 (Singapore: Singapore Free Press, 1835). (Microfilm NL5826)

Singapore Institution Free School, The Third Report of the Singapore Institution Free School 1836–1837 (Singapore: Singapore Free Press, 1837). (Microfilm NL5826)

Singapore Institution Free School, The Singapore Institution Free School Six Annual Report 1839–1840 (Singapore: Mission Press, 1840). (From BookSG: microfilm NL5826)

Singapore Institution Free School, The Singapore Institution Free School Fifth Annual Report 1838–1839 (Singapore: Mission Press, 1839). (Microfilm NL5826)

Singapore Institution Free School, The Singapore Institution Free School Seven Annual Report 1840–1841 (Singapore: Mission Press, 1841). (From BookSG: microfilm NL5826)

Singapore Institution Free School, The Singapore Institution Free School Eight Annual Report 1842–1843 (Singapore: Mission Press, 1843). (From BookSG: microfilm NL5826)

Singapore Institution Free School, Annual Report of the Singapore Institution Free Schools for the Year 1853 (Singapore: Mission Press, 1853). (From BookSG: microfilm NL5826)

Song Ong Siang, One Hundred Years of the Chinese in Singapore (London: John Murray, 1923). (From BookSG; call no. RRARE 959.57 SON-[LKL]; microfilm NL3280)

Sophia Raffles, Memoir of the Life and Public Services of Sir Stamford Raffles (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1991). (Call no. RSING 959.57021092 RAF)

Sophia Raffles, “Minutes by Raffles on the Establishment of a Malay College at Singapore 1819,” in Memoir of the Life and Public Services of Sir Stamford Raffles (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1991), 23–38. (Call no. RSING 959.57021092 RAF)

Sophia Raffles, “Singapore Institution,” in Memoir of the Life and Public Services of Sir Stamford Raffles (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1991), 75–82. (Call no. RSING 959.57021092 RAF)

Stuart Craig, South-East Asia (London: London Missionary Society, 1960). (Call no. RCLOS 275.9 CRA)

T. Braddell, Statistics of the British Possessions in the Straits of Malacca (Pinang: Pinang Gazette Printing Office, 1861). (Call no. RRARE 959.5 BRA; microfilm NL5560, NL15435)

Thomas Stamford Raffles, Statement of the Services of Sir Stamford Raffles (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1978). (Call no. RSING q325.3410959 RAF)

Walter Makepeace, “The Press,” in Twentieth Century Impressions of Malaya: Its People, Commerce, Industries, and Resources, ed. Arnold Wright and H.A. Cartwright (London: Lloyd’s Greater Britain Publishing Company Ltd., 1908), 253–66. (Call no. RCLOS 959.3 TWE-[SEA])

W.H. Medhurst, China: Its State and Prospects, With Special Reference to the Spread of the Gospel: Containing Allusions to the Antiquity, Extent, Population, Civilization, Literature, and Religion of the Chinese (London: John Snow, 1838). (Call no. RRARE 266.0230951 MED)

William Milne, A Retrospect of the First Ten Years of the Protestant Mission to China (Malacca: Anglo-Chinese Press, 1820)

William R. Roff, Bibliography of Malay and Arabic Periodicals Published in the Straits Settlements and Peninsular Malay States, 1876–1941: With an Annotated Union List of Holdings in Singapore, Malaysia and the United Kingdom (London: Oxford University Press, 1972). (Call no. RCLOS 016.0599923 ROF)