Chinese Dialect Groups and Their Occupations in 19th and Early 20th Century Singapore

Librarian Jaclyn Teo draws on published English resources from the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library, and explores why certain Chinese dialect groups in Singapore specialised in specific trades and occupations, particularly during the early colonial period until the 1950s.

the Hokkiens for their mee,

the Hainanese for their coffee,

and the Cantonese for their pee.”[^1]

— Li Yih Yuan, Yige Yizhi de Shizhen [一个移殖的市镇: 马来亚华人市镇生活的调查研究]

The above ditty is a common saying indicative of social stereotyping among Chinese dialect groups observed in Muar, Johor, in the 1950s. In fact, as far back as the 19th and early 20th centuries, there were already studies in Singapore highlighting the relationship between the occupations held by Chinese immigrants and their dialect origins (Braddell, 1855; Seah, 1848; Vaughan, 1874). Hokkiens and Teochews, being early settlers on the island, were known to dominate the more lucrative businesses, while later immigrants and minority dialect groups like Hainanese and Foochows were frequently regarded as occupying a lower position in the economic standings (Tan, 1990). Drawing on published English resources available in the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library, this article aims to explore why certain Chinese dialect groups in Singapore, such as Hokkiens, Teochews, Cantonese, Hakkas and Hainanese, seem to have specialised in specific trades and occupations, particularly during the early colonial period until the 1950s. It also posits some reasons why dialect group identities are no longer as dominant and obvious now as they used to be.

Chinese Migration to Singapore

Before delving into the occupational specialisation of each dialect group, it is important to first understand the social and economic background that resulted in the large-scale migration of Chinese from China to Singapore in the 19th century. During that time, life was extremely difficult in China; overpopulation resulted in a shortage in rice, a basic food staple, which led to inflation. Chinese peasants were also exploited by landlords, who imposed exorbitant rents on cultivable land to counter the high land taxes and surcharges levied by the Qing government. Natural calamities further aggravated the situation. From 1877 to 1888, for example, the drought in north and east China left close to six million people homeless and, without any aid from the government, many starved to death. Moreover, China was also mired in political turmoil. The Taiping Rebellion (1850–65), which originated in southern China, wiped out about 600 cities and towns, destroyed all the central provinces of China and adversely affected agricultural production, leading to widespread poverty and lawlessness. All these factors pushed many Chinese to go overseas in search of a better life (Yen, 1986).

Fortuitously, the founding of Singapore by the British in 1819, and the subsequent establishment of the Straits Settlements states of Penang, Melaka and Singapore by 1826 opened up numerous trade and work opportunities for the Chinese. In the last quarter of the 19th century, the discovery of tin in the Malayan states, as well as the large-scale development of rubber plantations, were additional pull factors for the Chinese to migrate to the region (Tan, 1986). The British brought about law and order in the Straits Settlements and initiated policies of free trade, unrestricted immigration (at least until the Aliens Ordinance was introduced in 1933 to limit the number of male migrants; Cheng, 1985) and non-interference in the affairs of the migrant population, all of which were advantageous to the Chinese migrants in search of economic advancement (Tan, 1986). Singapore, which came under direct British control as a crown colony in 1867, was not only the most important hub in the south of the Malayan Peninsula for the handling and processing of raw materials, it was also one of the major transit points where indentured labour from China and India were deployed to other parts of Southeast Asia. With a thriving economy, abundant job opportunities, and favourable British policies, large numbers of Chinese flocked to Singapore. In a letter to the Duchess of Somerset in June 1819, Stamford Raffles, the founder of modern Singapore, claimed that his “new colony thrives most rapidly… and it has received an accession of population exceeding 5,000, principally Chinese, and their number is daily increasing” (quoted in Song, 1923, p. 7). By 1836, the Chinese population (at 45.9%) had already surpassed the indigenous Malay community to become the major ethnic group in Singapore (Saw, 1969).

Formation of Trade Specialisations

Despite originating from the same country, the Chinese community in Singapore was not a homogeneous one, but was highly divided and fragmented (Tan, 1986). The Chinese came from different provinces in China and spoke different dialects: those who came from the Fujian province spoke Hokkien; the ones from Chaozhou prefecture spoke Teochew; people from Guangdong province spoke Cantonese, while those from Hainan Island spoke Hainanese. In addition, the dialect groups worshipped different local deities and considered their own traditions and customs to be superior to those of the others (Yen, 1986). As the different spoken dialects posed a significant communication barrier between groups, Chinese immigrants naturally banded together within their own provincial communities for security and assistance in this new environment (Yen, 1986). This phenomenon was further aided by Raffles’ plan to segregate the different groups (Braddell, 1854). In 1822, Raffles proclaimed that “in establishing the Chinese kampong on a proper footing, it will be necessary to advert to the provincial and other distinctions among this peculiar people. It is well known that the people of one province are more quarrelsome than another, and that continued disputes and disturbances take place between people of different provinces” (Song, 1923, p. 12).

How, then, did the trade specialisations based on dialect groupings come about? Cheng (1985) posited that the concentration of each dialect group in specific areas on the island provided a geographical and socioeconomic base for starting a trade. As more and more people of the same dialect group moved into the same area, the trade that was initially started by some would become increasingly established and entrenched. This was especially so because new migrants to Singapore tended to turn to their relatives (usually of the same dialect group) for jobs. Indeed, an early immigrant, Ang Kian Teck, confirmed this point. He related: “when you first arrive in Singapore, you find out what your relatives are doing and you follow suit. If your relatives are rickshaw pullers, then you too would become one. My elder brother was already in Singapore working as chap he tiam shopkeeper, so I joined him” (quoted in Chou & Lim, 1990, p. 28). It was also natural for experienced migrants, such as fishermen, artisans and traders, to continue with their specialised trades when they resettled. Factors such as the physical environment, as well as the intervention of secret societies, also contributed to the dominance of particular dialect groups in certain trades (Mak, 1981).

Mak (1995) puts forth several reasons to explain why such occupational patterns continued to persist. First, businesses which were capital-intensive, by the very fact that they required large amounts of resources, tended to exclude the poorer dialect groups. Close network ties within communities similarly prevented other dialect groups from participating in the same trades. The way trade groups were organised, and the formation of occupational guilds and the apprenticeship system, were successful in keeping businesses within certain dialect groups. Occupational guilds helped contain the supply of materials and information required for the trade within the dialect group. For example, the Singapore Cycle and Motor Traders’ Association, dominated by the Henghuas, ensured that the continuation of trade stayed within the same dialect group by encouraging members to take over the retiring businesses of fellow clansmen (Cheng, 1985). The apprenticeship system, which entails the passing of skills from one to another, was more effective when employers and trainees understood each other. Hence, the employer who was looking for an apprentice would tend to choose someone from the same dialect origin. Over time, the acquired reputation of a dialect group in a particular trade might also prevent other dialect groups from competing in the same trade successfully.

All the above factors reinforced one another and strengthen the dialect group’s position in that trade. As a result, the “consequence of dialect trade specialisation is that the particular dialect becomes the language of the trade. Dialect incomprehensibility among different dialect groups, dialect patronage, and trade associations are mutually influencing and reinforcing; and together they form a barrier by excluding members of other dialect groups from entry or effective participation. Thus, unless the conditions for dialect trade are disrupted, the trend of development is towards further consolidation and expansion” (Cheng, 1985, p. 90).

Dominant Trades for Major Dialect Groups

Hokkiens

Among the various dialect groups, the Hokkiens were among the earliest to arrive in Singapore. It was recorded that the first groups of Chinese to arrive in Singapore had come from Malacca and most of these early migrants were believed to be Hokkiens, then known as Melaka–born Chinese (Seah, 1848). Subsequently, Hokkiens from Quanzhou, Zhangzhou, Yongchun and Longyan prefectures of Fujian province also migrated to Singapore (Cheng, 1985). With a long history of junk trade involvement in Southeast Asia, it was natural for Hokkiens to continue to be active in commerce, working as shopkeepers, general agriculturalists, manufacturers, boatmen, porters, fishermen and bricklayers, according to an estimate made in 1848 (Braddell, 1855). In fact, Braddell noted that the Hokkien Melakan Chinese, who were Western educated and had prior interactions with European merchants, had “a virtual monopoly of trade at Singapore” in the 1850s (p. 115). Raffles also noted in a letter to European officials that the more respectable traders were found among the Hokkiens (Tan, 1986). The Hokkiens congregated and settled in Telok Ayer Street, which was near the seacoast, and this gave them an added advantage for coastal trade. All these propelled the Hokkiens to successfully establish a strong commercial footing on the island (Cheng, 1985).

The Hokkiens’ strong economic position allowed them to accumulate capital, which in turn gave them a higher chance of venturing into new businesses like rubber planting when the economy grew (Cheng, 1985). Hokkien capitalists were the first pioneers to invest in rubber planting, which was considered to be a riskier and more capital-intensive venture than gambier planting, as rubber could be tapped only after many years, and was also subjected to violent price fluctuations. The rubber boom during World War I and the Korean War strengthened Hokkiens’ economic position further and Hokkiens went on to control the speculative coffee and spice trade, as well as a number of banks, including the Ho Hong Bank (1917), Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation (1932), United Overseas Bank (1935), Bank of Singapore (1954) and Tat Lee Bank (1975), to name a few (Cheng, 1985).

Another well-documented trade specialisation among the Hokkiens (specifically those who came from Anxi of Quanzhou prefecture) was the chap he tiam business, otherwise known as the “mixed goods” store or retail provision store business (Chou & Lim, 1990). Well-known Hokkien personalities like Tan Kah Kee and Lee Kong Chian were also involved in the pineapple-canning business (Tan, 1999). All in all, Hokkiens dominated the more lucrative trades and had a lion’s share in the following fields: banking, finance, insurance, shipping, manufacturing, import and export trade in Straits produce, ship-handling, textiles, realty and even building and construction (Cheng, 1985).

Hokkiens were and continue to be the largest Chinese dialect group in Singapore, accounting for more than 40% of the overall Chinese population (Leow, 2001).

Teochews

The Teochews, who are sometimes known as the “Swatow People”, formed the second largest dialect group in Singapore (Tan, 1990), and originated largely from the Chaozhou prefecture in Guangdong province.

The Teochews were inclined towards agriculture, and their economic prowess was anchored in the planting and marketing of gambier and pepper (Tan, 1990). Records show that even before the arrival of the British in Singapore, some Teochew farmers and their gambier plantations were already on the island (Bartley, 1933). The first Teochews to arrive on the British colony were believed to have come from the Riau Islands (Cheng, 1985), which had a large Teochew settlement, and was a centre for gambier trade. With a free-port status offering a gateway to international markets, Singapore soon replaced Riau as the preferred gambier trading centre for many Teochew traders. Before long, the gambier and pepper trades in Singapore were dominated by Teochews, and in the 1840s, they made up more than 95% of the Chinese gambier and pepper planters and coolies (Braddell, 1855). Seah Eu Chin, a Teochew, was said to be the first Chinese to initiate the large-scale planting of gambier and pepper on the island and his plantation “stretched for eight to ten miles from the upper end of River Valley Road to Bukit Timah and Thomson Road” (Song, 1923, p. 20).

As gambier and pepper produce was transported to town via waterways, the Teochews tended to settle along the middle portion of the Singapore River. It was said that the Teochews on the left bank of the Singapore River were mainly involved in gambier, pepper and other tropical produce, while those on the right bank of the Singapore River virtually dominated the sundry goods and textile trades (Phua, 1950). The Teochews were also involved in the boat trade with Siam, Hong Kong, Shantou, Vietnam and West Borneo (Hodder, 1953), and had a dominant share in the trading of rice, chinaware and glassware as well (Cheng, 1985). The establishment of the Four Seas Communications Bank by leading Teochews in 1907 marked the peak of their economic strength.

Unfortunately, gambier cultivation declined in Singapore from 1850 as a result of soil exhaustion. This led many Teochews to move their base to Johor (Makepeace, et al, 1921). In addition, as chemicals increasingly replaced gambier as a dye, Teochews’ economic strength dwindled further.

Another group of Teochews was recorded to have settled in Punggol and Kangkar, along the northern coastal fringes of the island (Chou, 1990). Living close to the sea, they became experienced fishermen, boatmen, fishmongers and fish wholesalers. Their livelihood as fishermen was badly affected, however, when the Singapore government decided to phase out kelongs (the largest form of fish trap) in favour of fish farms in 1981.

Cantonese

Numbering 14,853 in 1881, the Cantonese were the third-largest dialect group after the Hokkiens and the Teochews.1 The Cantonese originated from the Pearl River Delta region, particularly from the Guangzhou and Zhaoqing prefectures in Guangdong province. They were sometimes labelled as “Macaus” as they had used Macau as their main port of emigration prior to the opening up of Hong Kong in 1842 (Tan, 1990). The first Cantonese to arrive in Singapore was believed to be Chow Ah Chi, who arrived in Singapore together with Stamford Raffles in 1819. One source mentioned that he was a carpenter from Penang (Cheng, 1985), while another source claimed that he was in fact the cook named Ts’ao Ah Chih on board Raffles’ ship (Tan, 1990). The Cantonese were among the first to arrive in Singapore, and they settled in the Kreta Ayer region as they preferred the elevated inland areas to the swampy waterfront district (Cheng, 1985).

The Cantonese were involved in a wide variety of occupations. Seah Eu Chin observed in 1848 that Cantonese and Hakkas were predominantly artisans. Similarly, William Pickering, who later became the First Protector of Chinese in Singapore, wrote in 1876 that most Cantonese and Hakkas in the Straits Settlements were miners and artisans. The Cantonese in Singapore were known to work as bricklayers, carpenters, cabinet-makers, woodcutters and goldsmiths. Cantonese women from San Sui (Three Rivers), in particular, were noted for their contribution to Singapore’s construction industry in the 1950s and 1960s (Tan, 1990). The Cantonese also opened a number of restaurants and herbal medical stores in Singapore during the late 19th century (Mak, 1995).

Vice was another trade that was reportedly linked to Cantonese (Mak, 1995). The Superintendent of Census remarked that most prostitutes were of Cantonese origin, and newspapers of that period reported that there were a few thousand prostitutes in the Kreta Ayer region, an area that was predominantly occupied by Cantonese. Although there were also Hokkien and Teochew brothels, their numbers decreased due to pressure from Hokkien leaders to close down Hokkien brothels in a bid to undo the shame brought to their dialect group, as well as a ban on the emigration of Teochew women from Chaozhou in the 1880s.

The trades engaged by the Cantonese were mainly craft-based and were small in scale. Such trades, when compared to the import and export businesses dominated by the Hokkiens, generated much less income and wealth. Thus, the Cantonese were generally regarded as less economically well-off than the Hokkiens and the Teochews.

Hakkas

Unlike the other dialect groups which were based in one or two prefectures, the presence of Hakkas was extensive throughout China. Known as the nomads of China, the southward migration to Southeast Asia was a natural progression for the community. The term “Hakka” is actually a Cantonese translation for “guest family”, or ke jia in Mandarin.

In Singapore, it was documented that the Hakkas had settled at South Bridge Road, North Bridge Road and the Lorong Tai Seng area in Paya Lebar (Tan, 1990), while Cheng (1985) also suggested that they had largely settled in Pasir Panjang, Lim Chu Kang, Chua Chu Kang, Kampong Bahru and Jurong.

Like the Cantonese, the Hakkas were involved in a wide range of craft-related occupations such as shoemaking, garment manufacturing , tailoring and jewellery making. Estimating the numbers and occupations of Chinese in Singapore in 1848, Braddell (1855) recorded that there were about 1,000 Hakkas working as house carpenters, 800 involved as woodcutters, 600 as shopkeepers and traders, 500 as blacksmiths, 400 as tailors and shoemakers, 200 as cabinet makers, 100 as goldsmiths and 100 as barbers. The Hakkas (together with the Cantonese) in the Straits Settlements were also recognised by Pickering in 1876 as miners and artisans. Mak (1995) suggested that the Hakkas did not seem to like sea-related work, as there was no evidence of any Hakkas working in or near the sea although there were records of Hokkien longshore men, Cantonese boat-builders, and Teochew fishermen.

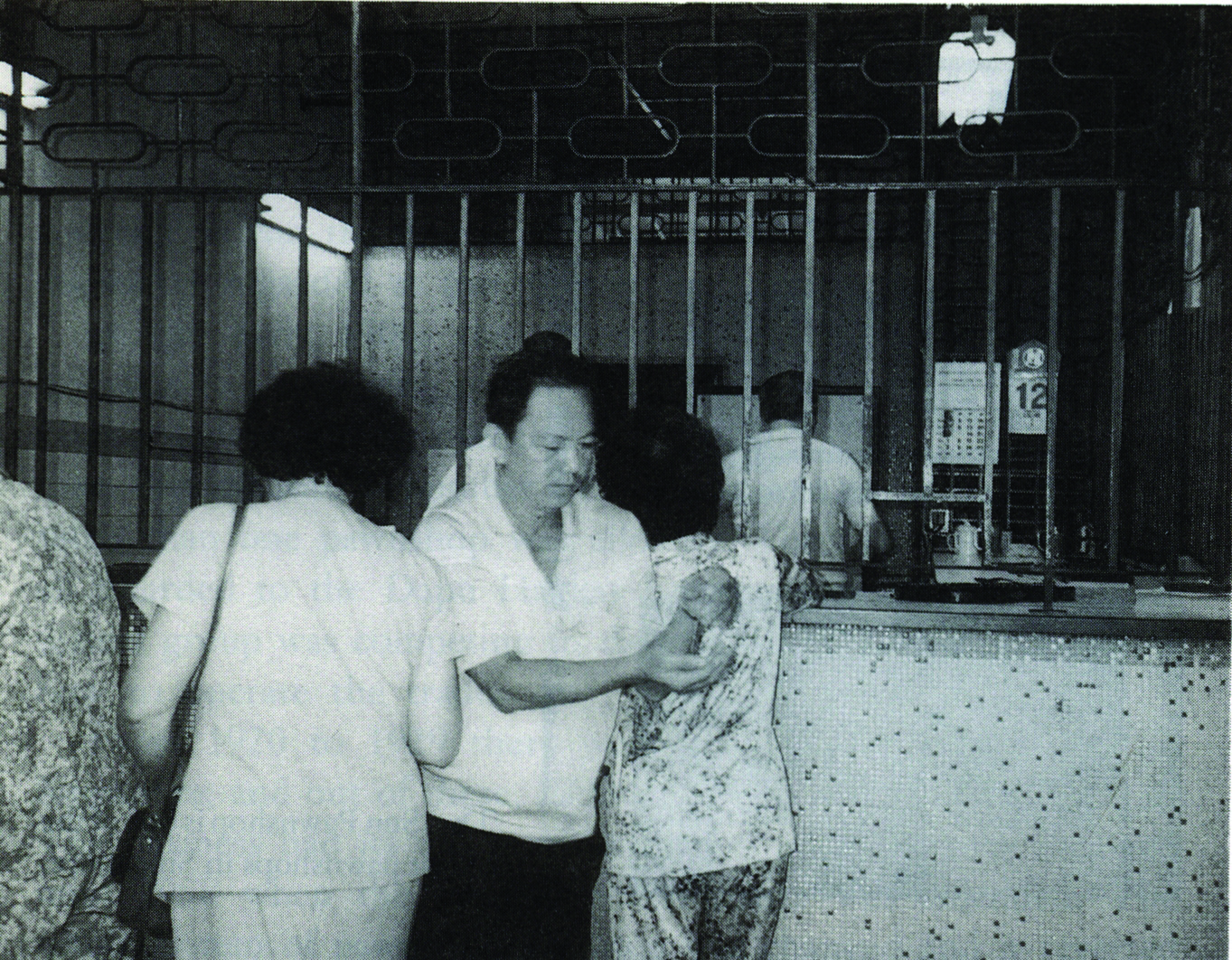

Two trades engaged by the Hakkas warrant special mention. Pawnbroking was one of them. Regarded as the “poor man’s bank”, pawnshops had more than one hundred years of history in Singapore (Cheng, 1985). Pawnbroking was a service that the poor could utilise to get quick cash in return for a pledge of their valuables. According to Tan and Chua (1990), the Hakkas seemed to have dominated this trade right from the beginning. In 1880, Singapore did not have any pawnshops, but the British government subsequently decided to kick-start the industry by issuing pawnshop licences to applicants who were willing to pay a fee of $200 per annum. A Dabu Hakka, Ho Yuen Oh, pioneered this industry by successfully obtaining the licences to operate the first eight pawnshops in Singapore. Since then, the Hakkas have dominated this trade.

Another trade worth noting was the Hakkas’ participation in the textile trade. The textile trade was initially dominated by Teochews and Hokkiens, but the Hakkas managed to compete and gain a slice of the market share by directing their textile exports to Johor Bahru, Melaka, Ipoh and some parts of Indonesia, all of which were not covered by the other two dialect groups (Cheng, 1985).

Hainanese

The Hainanese originated from Hainan Island, which was under the jurisdiction of Guangdong province. Most Hainanese in Singapore had come from either the Wencheng or Qiongzhou districts of Hainan Island (Tan, 1990). Some Hainanese still address themselves as “Kheng Chew Nang” (people of Kheng Chew), the old name for Hainan Island. Currently, the Hainanese are the fifth-largest dialect group in Singapore, constituting 6.69% of the Chinese population (Leow, 2001).

The Hainanese migrated to Singapore much later than the other dialect groups, mainly because of the late opening of Hainan Island to foreign trade when Hankou was made a treaty port in 1870. Cheng (1985) noted that there was a lack of Hainanese presence in Singapore in the first 20 years after the island’s founding, and the first Hainanese association in Singapore was established only in 1857. This late migration affected the Hainanese economically and left them with few employment choices as early settlers such as the Hokkiens and the Teochews had by then established a firm foundation in the more lucrative businesses like commerce, trade and agriculture. With no business contacts, and possessing a dialect that was not comprehensible to most other groups, the Hainanese found it difficult to break into the commercial sector. They eventually carved a niche for themselves in the service industries, dominating a range of occupations largely associated with food and beverages, such as coffee stall holders and assistants, bakers, as well as barmen and waiters in local hotels and restaurants (Yap, 1990). In fact, the signature local concoction ”Singapore Sling” was said to be created by Ngiam Tong Boon, a Hainanese bartender who worked at the Raffles Hotel (Conceicao, 2009). Many Hainanese also found jobs as domestic servants or cooks for European families and rich Peranakan households. It was not unusual for a British family to hire a Hainanese couple with the husband taking charge of both the cook’s and butler’s responsibilities while the wife would assume the role of a housekeeper (Yap, 1990). The experience of working for these European and Peranakan families equipped the Hainanese with the culinary skills they are known for even today – Western food and Nyonya cuisine. Due to their jobs in European households and the military bases, clusters of Hainanese could be found in the Bukit Timah, Tanglin, Changi and Nee Soon areas (Tan, 1990).

Hainanese influence could also be found in the areas around Beach Road and Seah Street. These places were peppered with Hainanese coffee shops, a trade that the Hainanese dominated until the 1930s (Yap, 1990). The Hainanese chose to enter the food trade as it did not require a large amount of capital investment. They were able to set up simple coffee stalls with just a few pieces of furniture by the roadside serving coffee to the masses. From such humble beginnings, the Hainanese eventually progressed and moved their businesses to better locations in shophouses when the rentals for shophouses fell during the Depression years. However, Hainanese dominance in the coffee shop trade waned in the 1930s and gave way to Foochows instead, who operated bigger ventures, were better able to cooperate and were more willing to take advantage of bank loans (Yap, 1990).

Other Dialect Groups

Other dialect groups that existed in Singapore included the Foochows (who dominated the coffee shop trade after the 1930s), the Henghuas and the Hokchias (who specialised in the rickshaw and bicycle trades) and the Shanghainese (otherwise known as the Waijiangren or Sanjiangren) who were involved in the tailoring, leather goods, antiques, cinema entertainment and sundry goods businesses (Cheng, 1985).

Erosion of Dialect Group Identity

In the past, dialect group identity played an important role in the choice of occupational specialisation among the early Chinese immigrant society. However, the same cannot be said for today. Mak (1995) had, in fact, commented that dialect group identity was by now a “social reality of the past” (p. 189).

There are a number of factors that have brought about this change, one of which could be occupational differentiation. When the island was first founded, the jobs available to the new immigrants were labour-intensive ones that were mostly associated with the primary sectors. The requirements for jobs were similar and employers tended to hire based on similar dialect origins, which also guaranteed similar language, culture and a certain level of trust (Mak, 1995). As the economy advanced and grew, jobs grew in complexity and required different skill sets. As a result, employers began to hire according to one’s skills or education rather than dialect group association. The presence of job placement and training agencies also perpetuated the importance of skills in a successful job search.

A second reason for dialect group erosion could be the decreasing need to maintain ties with clansmen (Tan, 1986). Early immigrants felt a need to band together within similar dialect groups for security and support in a new environment. However, generations later, there is a much lesser sense of cultural affinity to China, and a greater focus on nation-building in a multicultural Singapore instead.

Another important factor that contributed to the erosion of dialect group identity would be the Speak Mandarin Campaign launched in 1979, which promoted the use of Mandarin as a common language in a bid to unify the Chinese of different dialect groups.

Conclusion

Early Chinese settlers who migrated to Singapore in the 19th and early 20th centuries banded together in their respective dialect groupings for security and support in a new environment, which reinforced the occupational specialisations associated with special dialect groups. The Hokkiens, being early arrivals, had gained a lion’s share in lucrative trades like commerce, banking, shipping, and manufacturing, while the Teochews were mostly agriculturalists and their financial strength was anchored in the planting and marketing of gambier and pepper. The Cantonese dominated the crafts-related trades, the Hakkas in pawnbroking, and the Hainanese featured prominently in the services sector. While patterns could be observed between the types of occupations and dialect groups, it should be pointed out that the situation of “one dialect group one occupation” never existed and could only be regarded as a myth (Mak, 1995). Hence, even when a dialect group dominated a particular trade, there might still exist minority members from other dialect groups who were involved in the same trade.

Today, dialect groupings no longer play such an important role in occupational choice. While employers in the past tended to hire based on similar dialect origin, such clan affiliations are no longer as important in today’s recruitment scene, and have given way to other employment considerations such as educational qualifications and suitable skill sets instead.

Librarian

Lee Kong Chian Reference Library

National Library Board

REFERENCES

B.W. Hodder, “Racial Groupings in Singapore,” The Journal of Tropical Geography 1 (1953), 25–36. (Call no. RCLOS 910.0913 JTG; microflm NL10327)

Bonny Tan and Jane Wee, “Tan Kah Kee,” Singapore Infopedia, published 2016.

Cheng Lim-Keak, Social Change and the Chinese in Singapore: A Socio-Economic Geography With Special Reference To Bang Structure (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1985). (Call no. RSING 369.25957 CHE)

Cynthia Chou, “Teochews in the Kelong Industry,” in Chinese Dialect Groups: Traits and Trades, ed. Thomas T.W. Tan (Singapore: Opinion Books, 1990), 38–50. (Call no. RSING 305.8951095957 CHI)

Cynthia Chou and Lim Puay Yin, “Hokkiens in the Provision Shop Business,” in Chinese Dialect Groups: Traits and Trades, ed. Thomas T.W. Tan (Singapore: Opinion Books, 1990), 21–37. (Call no. RSING 305.8951095957 CHI)

J.D. Vaughan, The Manners and Customs of the Chinese (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1974). (Call no. RSING 390.0951 VAU)

Jeanne Louise Conceicao, “Hainanese Community,” Singapore Infopedia, published 2009.

Leow Bee Geok, Census of Population 2000: Demographic Characteristics. Statistical Release 1 (Singapore: Department of Statistics, Ministry of Trade and Industry, 2001). (Call no. RSING q304. 6021095957 LEO)

Li Y.Y., Yige yi zhi de shi zhen: Ma lai ya huaren shi zhen shenghuo de diaocha yanjiu 一個移殖的市鎮:馬來亞華人市鎮生活的調查研究 [An immigrant town: Life in a Chinese immigrant community in Southern Malaya] (Taipei: Institute of Ethnology, Academemia Sinica, 1970)

Mak Lau Fong, The Sociology of Secret Societies: A Study of Chinese Secret Societies in Singapore and Peninsula Malaysia (New York: Oxford University Press, 1981). (Call no. RSING 366.095957 MAK)

Mak Lau Fong, The Dynamics of Chinese Dialect Groups in Early Malaya (Singapore: Singapore Society of Asian Studies, 1995). (Call no. RSING 305.89510595 MAK)

Maurice Freedman, “Immigrants and Associations: Chinese in Nineteenth Century Singapore,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 3, no. 1 (October 1960), 25–48. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Pan Xingnong, Ma lai ya chao qiao tong jian 马来亚潮侨通鉴 [The Teochews in Malaya] (Singapore: South Island Publisher, 1950). (Call no. RCLOS. 305.895105951 PXN)

Saw Swee-Hock, Singapore Population in Transition (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1970). (Call no. RCLOS 301.3295957 SAW)

Seah U. C., “The Chinese in Singapore,” Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia 2, no. 9 (1848), 283–89. (From BookSG; RRARE 950.05 JOU; microfilm NL25790)

Song Ong Siang, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore (London: Murray, 1923). (From BookSG; call no. RRARE 959.57 SON; microfilm NL3280)

Thomas Braddell, “Notices of Singapore,” Journal of Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia 8, no. 4 (1854), 101–10. (Call no. RRARE 950.05 JOU; microfilm NL25796)

Thomas Braddell, “Notes on the Chinese in the Straits of Malacca,” Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia 9, no. 2 (1855), 109–24. (Call no. RRARE 950.05 JOU; microfilm NL25797)

Thomas T.W. Tan, ed., Chinese Dialect Groups: Traits and Trades (Singapore: Opinion Books, 1990). (Call no. RSING 305.8951095957 CHI)

Thomas Tsu-Wee Tan, (Singapore: Times Books International, 1986). (Call no. RSING 301.451951 TAN)

W.A. Pickering, “The Chinese in the Straits of Malacca,” Fraser’s Magazine (October 1876), 440.

W. Bartley, “Population of Singapore in 1819,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 11, no. 2 (December 1933), 177. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Walter Makepeace, Gilbert E. Brooke and Roland St. J. Braddell, One Hundred Years of Singapore, vol. 1. (London: John Murray, 1921). (Call no. RCLOS 959.57 ONE)

Yap M.T., “Hainanese in the Restaurant and Catering Business,” in Chinese Dialect Groups: Traits and Trades, ed. Thomas T.W. Tan (Singapore: Opinion Books, 1990), 78–90. (Call no. RSING 305.8951095957 CHI)

Yen Ching-Hwang, A Social History of the Chinese in Singapore and Malaya 1800–1911 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1986). (Call no. RSING 301.45195105957 YE)

NOTES

claimed that between the years 1891 and 1947, the Cantonese were the second-largest group after the Hokkiens, and were only overtaken by the Teochews in numbers after 1947.

-

Cheng Lim-Keak (Social Change and the Chinese in Singapore: A Socio-Economic Geography With Special Reference To Bang Structure (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1985). (Call no. RSING 369.25957 CHE)) ↩