The Case of Tras New Village and the Assasination of Henry Gurney During the Malayan Emergency

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow Tan Teng Phee delves into the fate of Tras New Village and its residents during the Malayan Emergency.

How miserable Tras resettlement was

Here another meal with dried and salted fish

A deeply bitter experience we suffer in silence”

— Hakka song composed by Tras New Villagers at the Ipoh detention camp

On 16 June 1948, after the murder of three European rubber estate managers in Sungai Siput, Perak, the British colonial government declared a state of emergency in Malaya. The British considered the murders to be the mark of an outbreak of armed communist insurgency; thus, the mass resettlement programme put in place by the British thereafter was designed to isolate and defeat the communists, and simultaneously win the hearts and minds of the rural people. By the end of the Malayan Emergency on 31 July 1960, half a million rural dwellers had resettled into 480 New Villages, 450 of which are still scattered across the Malay Peninsula today. In 1951, Tras New Village became a focal point of British anticommunist imperatives and the Malayan Emergency.

Tras was an old tin mining settlement in the state of Pahang during the early 20th century and became a rubber-rich area before World War II. Tras New Village, a rural Chinese community contiguous to Tras, was established by the British in 1951. Located approximately 100 km from Kuala Lumpur, its two nearest neighbouring towns are Raub (13 km) and Bentong (20 km). It currently has a population of approximately 1,000, in both its town and new village areas. There is a 20-km winding road near Tras, leading to Fraser’s Hill, a famous hill resort during the colonial era.

Tras New Village is a distinct case because it is located near the spot where British High Commissioner Henry Gurney was assassinated on 6 October 1951. On that fateful morning, a group of communists ambushed and killed the High Commissioner on the Kuala Kubu Bahru-Fraser’s Hill Road, just seven miles (11 km) from Tras. This tragic incident had a significant impact on the nature of the unfolding Malayan Emergency, as well as on life and prospects for the Tras villagers.

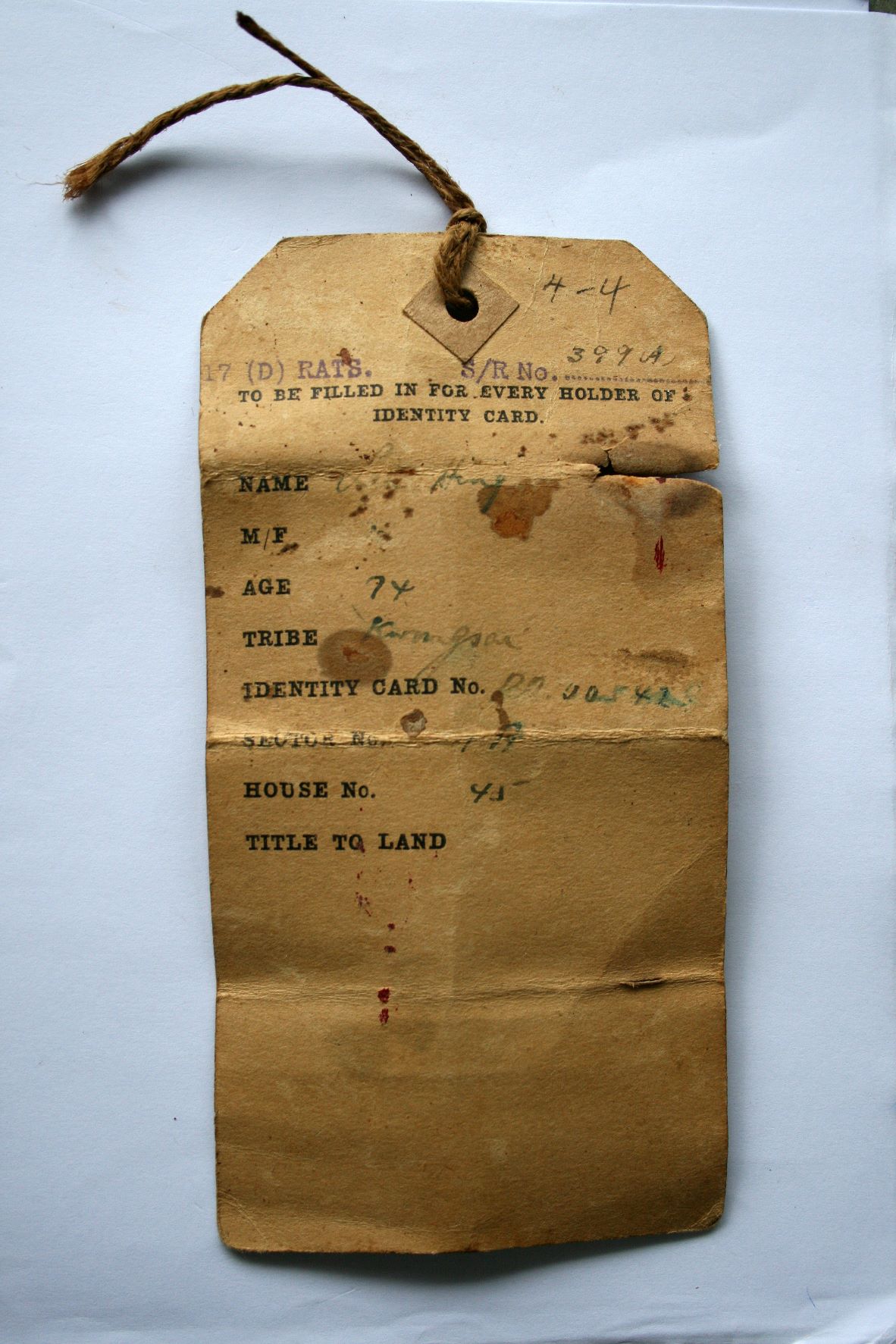

Until recently, the personal accounts and individual memories of New Villagers have largely remained untold in the public narrative. According to official accounts, a typical New Village usually possessed basic amenities such as a police station, a school, a dispensary, a community hall, piped water and electricity. However, in practice, the implementation of such amenities was often hindered by a lack of resources (money, staff and materials) and rapid demand for the establishment of new villages by the government during the Emergency. In addition, the villagers were confined and protected by a barbed wire fence that surrounded their villages and were placed under strict control and surveillance. Surveillance methods included curfews, body searches at checkpoints, food restrictions as well as tenant and Identity Certificate registration.

This study adopts a “history from below” perspective to document the social experience of resettlement and life behind the barbed wire fences for the residents in the New Villages. It re-examines and analyses how the assassination of the British High Commissioner to Malaya in 1951 both implicated and changed the lives of Tras New Villagers during the Emergency. By examining the experiences of Tras New Villagers through oral accounts and interviews, this micro-level study brings attention to the significant impact of the Emergency, including the displacement and forced relocation of this particular rural Chinese community.

The Assassination of Henry Gurney

On 6 October 1951 at 11 am, Henry Gurney and Lady Gurney, together with their Private Secretary D. J. Staples, left King’s House, Kuala Lumpur, for Fraser’s Hill. They were accompanied by an armed convoy consisting of three military vehicles with 13 police personnel. Around 1:15 pm, heavy firing broke out suddenly as they were negotiating an “S” bend between the 56th and 57th mile. The communists had ambushed the party about two miles from the Gap Road and about eight-and-a-half miles from Fraser’s Hill.

All the police constables in the Land Rover were injured by the first burst of gunfire, but they managed to return fire. Meanwhile, a second wave of communist gunfire was directed at Gurney’s Rolls-Royce and shattered its windscreen, hitting Gurney’s Malay driver, Mohamed Din. He managed to stop the vehicle, but the stationary car then drew more concentrated gunfire. At this moment, Gurney opened the door and got out of the car, drawing fire away from it. Gurney was killed instantly as he attempted to cross the road.1 Two days later, an official funeral was held in Kuala Lumpur for Gurney, who was then buried in the cemetery on Cheras Road in Selangor.2

The people of Malaya were profoundly shocked by news of the tragic death. At a press conference, the Commissioner of Police, W.N. Gray, stated that Gurney’s car had been hit by bullets 35 times.3 Investigations suggested that the communists had in fact been seeking to acquire weapons, and not targeting the High Commissioner.4 Chin Peng, Secretary-General of the Malayan Communist Party, confirms this in his memoir, that the communist ambush had intended “to attack a large armed convoy” and “to seize as many weapons and as much ammunition as the comrades could carry away”.5 It was therefore by accident, rather than by design, that the communist platoon ambushed and killed Gurney on the Gap Road.

Impact on the Tras Community

Immediately after the tragedy, the colonial government conducted a combination of military, police and air strike operations. There was heavy shelling and bombing of the jungle day and night for nearly a month. Under strict curfew, the villagers were not permitted to go out to work, only to purchase daily essentials from the local grocery shops in the town area, which opened for business two hours a day. Several elderly informants complained about the loss of income during this period, especially as rubber prices were high at that point in time.

A month after the death of Gurney, the British called off their military operations in the jungle and turned their attention to Tras New Village, which was located seven miles from the assassination scene.6 The British claimed that Tras had become the main source of food supplies for the communist guerrillas in western Pahang. The police also suspected that the Tras villagers had supported communist activities in the area.7 Based on its past “notoriety”, Tras inhabitants were considered “terrorist sympathisers and helpers” by the British.8 Most importantly, they were suspected of aiding and abetting “the gang which murdered Sir Henry Gurney”.9 In response to their unwillingness to comment, the colonial government initiated an evacuation and the mass detention of Tras inhabitants in November 1951.10

The evacuation scheme unfolded in two phases over two days. The first phase, on 8 November 1951, involved evacuating 1,460 Tras New Villagers, while the second phase on the following day saw the removal of another 700 people. The colonial government successfully removed a total of 2,160 men, women and children from Tras New Village and the town area in a short period of time. They were transferred by lorry and train to the Ipoh Detention Camp in Perak, over 240 km away from their hometown. It was the first mass removal and detention of Chinese New Villagers in a barbed wire fenced resettlement camp since the beginning of the Emergency.

Elderly villagers clearly recall several Assistant Resettlement Officers and local Chinese leaders announcing the British decision on the evacuation. The villagers were given a day to pack their belongings before being transported to the Ipoh detention camp. Many of the elderly informants shared with me that each person was allowed to carry only “one shoulder pole with two baskets” (一人一擔). Then, the Pahang State War Executive Committee sent a working team to each house to assess their livestock, rubber holdings and chattels. Every head of household was then given a government-stamped receipt for any valuable goods left behind. The village was told that they would be credited with a percentage of the total proceeds from the sale of their goods at the Raub town market. However, all my interviewees said that this never came to pass.

At dawn on 7 November 1951 before the evacuation commenced, many villagers prayed to their gods and at their ancestral altars for a safe journey and protection. They burned joss sticks and made offerings with their slaughtered poultry to propitiate their gods and ancestral spirits. The first troops arrived at around 6 am and evacuation orders were broadcast over a mobile loudspeaker. The villagers collected their shoulder poles and assembled in the Tras town area between 6 and 8 am. On their way to Tras, each family had to pass through a gauntlet – a double row of detectives and uniformed police officers guarding an armoured vehicle. Inside the vehicle were communist informants tasked with screening the villagers as they walked by.

Several female interviewees vividly remembered the heartbreaking scenes when family members were separated from one another during the screening operation. An old lady cried out in vain as she was forcefully separated from her young daughter who was taken away by the police. A few elderly ladies wept with the mother while trying to console her.11 Out of 1,460 people screened, a total of 20 villagers (5 women and 15 men) were detained on suspicion of being communist supporters and food smugglers.12

More than 100 vehicles, including buses, lorries and trucks, were utilised on the first day to transport the Tras villagers. The evacuation team had air cover from Brigand bombers and ground protection from armoured escorts all the way to the Kuala Kubu Bahru railway station. Upon their arrival at the rail siding that afternoon, the Kuala Kubu Bahru branch of the Malayan Chinese Association prepared meals for the villagers at the railway station. They then boarded a special 14-coach train, which transported them to Ipoh. From the Ipoh railway station, the villagers were escorted by armed police and radio vans, and taken in military trucks to the detention camp two miles away.13 It was around 7 pm when they arrived at the Ipoh Detention Camp. Each family was then assigned a small cubicle in a wooden long-house inside the camp as their “new home”.

The remaining 700 residents in Tras made preparations for their evacuation the following day. Several towkays requested for permits to allow their relatives or friends in Raub to help them sell their goods at the Raub market.14 The collective value of the Tras people’s stocks of rubber and food surprised the government officers. The total value of movable property – cars, bicycles, textiles, liquor, rice and other goods from their shops – was an estimated $3,500,000,15 making it one of the richest communities in Pahang. The next morning, on 9 November 1951, the British evacuated the remaining 700 inhabitants from the town area. By late 1951, Tras had become a ghost town.16

The Ipoh Detention Camp was situated about 5 km from Ipoh.17 All my interviewees had distinct memories of the government’s interrogations at the detention camp. In their investigations of British accusations that the residents of Tras Village had “bred, harboured and helped the murderers of Sir Henry Gurney”, the police screened 1,154 adults in the first three months at the Ipoh Detention Camp. Shortly after the interrogations, the first batch of 485 villagers was unconditionally released from the detention camp in late February 1952. The second batch – another 400 people – was released in mid-March, while those remaining were detained for further interrogations.18 Two of the villagers I spoke with said they were detained for between one and two years at the camp without being given any reason.19

As a result of the mass interrogations at the Ipoh camp, the British detained a total of 37 Tras inhabitants who were accused of having “helped the murderers of Sir Henry Gurney”.20 The rest of the Tras villagers were gradually released in batches from February 1952 onwards. They were resettled in various New Villages in Pahang but prohibited from returning to Tras. For the first and second batch of released villagers, the British authorities expanded a section of Sempalit New Village, about 15 km from Tras, to accommodate 200 detained families from the Ipoh Detention Camp. Each family was assigned a house in the New Village.

Oral history accounts reveal that some Tras villagers chose to settle at Sungai Raun New Village, about 23 km from Tras. The State government provided each relocated family with a house lot and four acres of land for cultivation. Other families decided to move to Jerkoh New Village, or Bukit Tinggi New Village, to work as farmers. Those who preferred to become rubber tappers resettled at Sanglee New Village, Sungai Chetang New Village and Sungai Penjuring New Village, all located within a 30 km radius of Tras. These New Villages were enclosed within barbed wire fencing and the villagers were subjected to regular body searches, food control measures, curfews and other restrictions. Some Tras families, however, sought direct assistance from their relatives in various towns and cities, such as Kuala Kubu Bahru, Bentong, Ipoh and Kuala Lumpur. Hence, Tras people were scattered widely across different New Villages and towns shortly after their release from the detention camp.

The Return to Old Tras

It was not until December 1954 that the British government reopened Tras and allowed local rubber estate owners to return to tap their trees. Since the devastated Tras was overgrown with weed and shrub after more than five years of neglect, it took the authorities and former residents nearly two years to renovate shops and rebuild houses in the old village. Besides purchasing a house from a construction company, each returned family could also apply for four acres of land to plant rubber trees or other cash crops.21 The first group of Tras former inhabitants, made up of about 40 families (250 people), returned to their hometown on 23 September 1957.22 Six months later, the local government administration held an official opening to mark Tras’ rebirth; this was six years after it was evacuated.23 By June 1958, more than 600 people had returned to Tras.24 It was estimated that about one-third of the 2,160 former residents had moved back to Tras by the end of the Emergency in July 1960.25

Private speculation and individual memories challenge the authority of the official account of the assassination and the subsequent evacuation and mass detention. There is a range of opinions with regards to why Henry Gurney stepped out of his car at the height of the communist ambush. The official account suggests that he wanted to draw away the concentrated fire that might otherwise have killed his wife and his private secretary. He was portrayed in The Straits Times, the national newspaper, as a hero who sacrificed his life to save others.26

Interestingly, one elderly informant opined that the “Imperial Commissioner” simply wanted to approach and negotiate with the communists but was unfortunately killed.27 In an informal group conversation in a Tras coffee shop, one elderly villager firmly expressed the opinion that the communists made a mistake in murdering the “Imperial Commissioner” at the Gap Road. He alleges that he heard that the “Imperial Commissioner” had a secret file ready for submission to the Queen, which would allow the Malayan Chinese to share equal political power with the Malays in future. Because of the assassination and subsequent state of emergency, the colonial government later decided to transfer political power solely to the Malays.28 There is no official evidence to support this point of view, but it reveals the perspectives of the relocated villagers, and how they relate their present to the past, as well as how such memories and alternate narratives become integrated with their understanding and explanation of their present political and social status in Malaysia.

In the oral accounts I collected, a common response to the evacuation was: “There was nothing you could do.” A number of interviewees mentioned the severity of their economic loss from forced unemployment as well as the feeling of insecurity and fear during the period of evacuation and mass detention. The subsequent resettlement once more into different New Villages further exacerbated their economic loss due to the government restriction on returning to their smallholdings for the following five years.

Conclusion

To the British, both in Whitehall (London) and King’s House (Kuala Lumpur), the assassination of the High Commissioner drew worldwide attention to the grave deterioration of security in Malaya.29 While the forced evacuation and collective detention of 2,156 Tras people had its critics, the British government defended these operations as necessary to clear an extremely dangerous area and separate the “sheep from the goats”, in order to avoid punishing innocent people in the area.30 From the perspective of the Tras people, the summary use of Emergency Regulation 17D following the death of Henry Gurney had a profound impact on their lives.31 The old, prosperous, rubber-rich town quickly became a ghost town in the aftermath of the evacuation and mass detention of November 1951. One key informant likened Tras to “a bamboo plant suddenly being cut through the middle… and which would take a long time to recover”.32

In the context of the Emergency, the history of Tras is illustrative of an extreme set of circumstances. The assassination of the High Commissioner not only altered Tras’ historical trajectory; the mass detention and collective punishment further displaced and dispersed the Hakka community in Malaya. The Tras people bore the heavy costs of this tragic event, enduring family separation, considerable emotional trauma and financial hardship during the Emergency period and in the decades after.

The author wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Dr James Francis Warren, Professor of Southeast Asian Modern History, Murdoch University, in reviewing this research essay.

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow (2009)

National Library

NOTES

-

“Ambush: Official Story,” Straits Times, 8 October 1951, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Wife Stayed With Body for 45 Minutes,” Straits Times, 8 October 1951, 1; “The Funeral Tomorrow,” Straits Times, 7 October 1951, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

See “Troops Search Ambush Area,” Straits Times, 8 October 1951, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“No Evidence of Breach in Security,” Straits Times, 9 October 1951, 1. (From NewspaperSG). Among these documents were bandits’ plans for an ambush in that area and a log of military vehicles passing on October 5 and the morning of October 6. See “Troops Search Ambush Area.” ↩

-

Chin Peng, Alias Chin Peng: My Side of the History (Singapore: Media Masters Pte Ltd., 2003), 287. ↩

-

According to one government statement, 15 battles had occurred in the Tras area since the outset of the emergency, leaving 20 people dead and 14 wounded. In addition, the authorities had recorded 25 cases of attempted murder. The security forces has also discovered 24 “supply dumps” and 52 “bandit camps” in the vicinity of the town over the past three years. See Leslie Hoffman, “‘Terror’ Town to Be Moved,” Straits Times, 8 November 1951, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tras was reported as “a favourite haunt of the gang and police suspect that the bandits have many friends in the village and its resettlement area”. See “Killer Gang Slips Out of the Trap,” Straits Times, 18 November 1951, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Hoffman, “‘Terror’ Town to Be Moved.” ↩

-

Hoffman, “‘Terror’ Town to Be Moved.” ↩

-

Hoffman, “‘Terror’ Town to Be Moved.” ↩

-

It was said that the daughter was later deported to China. Interview with Madam Leong by the author on 2 December 2007. ↩

-

“20 Detained in Village Screening,” Straits Times, 9 November 1951, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Tras Evacuation Ends: 2,000 Quit,” Straits Times, 10 November 1951, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

For instance, Mr Lau, a grocery owner, asked his brother to transport his goods to the former’s grocery shop in Raub. Interview with Mrs Lau by the author on 12 December 2007. Another informant said his father asked a friend to sell his medicinal goods in Raub. His father lost a lot of money since it had to be sold in such a short time. Interview with Mrs Tang by the author on 19 October 2007. ↩

-

A newspaper reported that government agents bought $70,000 worth of rubber from the dealers at Tras. There was also about $50,000 worth of rice in storage, including bags of first-grade Siamese rice. One of the liquor shops had 62 uonpened cases of brandy and showcases full of other types of liquor. Government teams also recorded $100,000 worth of textiles in the shops. “Doomed Town Has Hoarded Fortune in Food, Drink,” Straits Times, 9 November 1951, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Interview with Mr Li by the author on 5 July 2007. The site is now a state stadium. I visited the spacious stadium which could accommodate three to four thousand people when it was a detention camp in the 1950s. ↩

-

“37 Held From ‘Murder Village’,” Straits Times, 13 March 1952, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Interview with Mr Tao with the author on 26 November 2007; Interview with Mr Lee by the author on 3 December 2007. ↩

-

There were two types of houses, 60 x 60 feet and 60 x 120 feet, which still stand today in Tras New Village. It cost $2,700 and $3,700 for a small and large house, respectively. Interview with Mr Li by the author on 12 December 2007. The Federation Housing Trust also provided $500,000 in loans to enable former villages to purchase their houses. See “Second Chance,” Straits Times, 19 September 1957, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“‘Ghost Town’ Booms Again,” Straits Times, 11 January 1958, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Jeffrey Francis, “Snip! Terror Town Tras Comes to Life Again,” Straits Times, 27 April 1958, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“‘Ghost Town’ Now Has 600 People,” Straits Times, 2 June 1958, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Interview with Mr Li by the author on 12 December 2007. ↩

-

“Sir Henry Gurney Killed – He Drew Bandit Fire,” Straits Times, 7 October 1951, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Interview with Mr Chang by the author on 12 December 2007. Sempalit New Village. The local Chinese used to address the British High Commissioner as “Imperial Commissioner” (in Chinese). ↩

-

Author’s interview with villagers in a coffeeshop in Tras New Village on 2 December 2007. ↩

-

The newly elected Prime Minister Winston Churchill sent his colonial secretary, Oliver Lyttelton, from United Kingdom to Malaya to assess the political situation himself. ↩

-

For instance, The Manchester Guardian questions: “Does such indiscriminate action really impress”? See collective punishment in Malaya, 1950–1951. (1952, December 16). Note for secretary of state brief, Kenya debate, CO 1022/56. ↩

-

In fact, Tras was the 17th village to be punished under the draconian Emergency regulation 17D. The British authorities had already applied the same regulation in 16 other places, involving almost 8,000 people since 1949. See “18th Village To Get 17D Penalty,” Straits Times, 8 November 1951, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Interview with Mr Li by the author on 12 December 2007. ↩