Women’s Perspectives on Malaya: Isabella Bird on the Chersonese

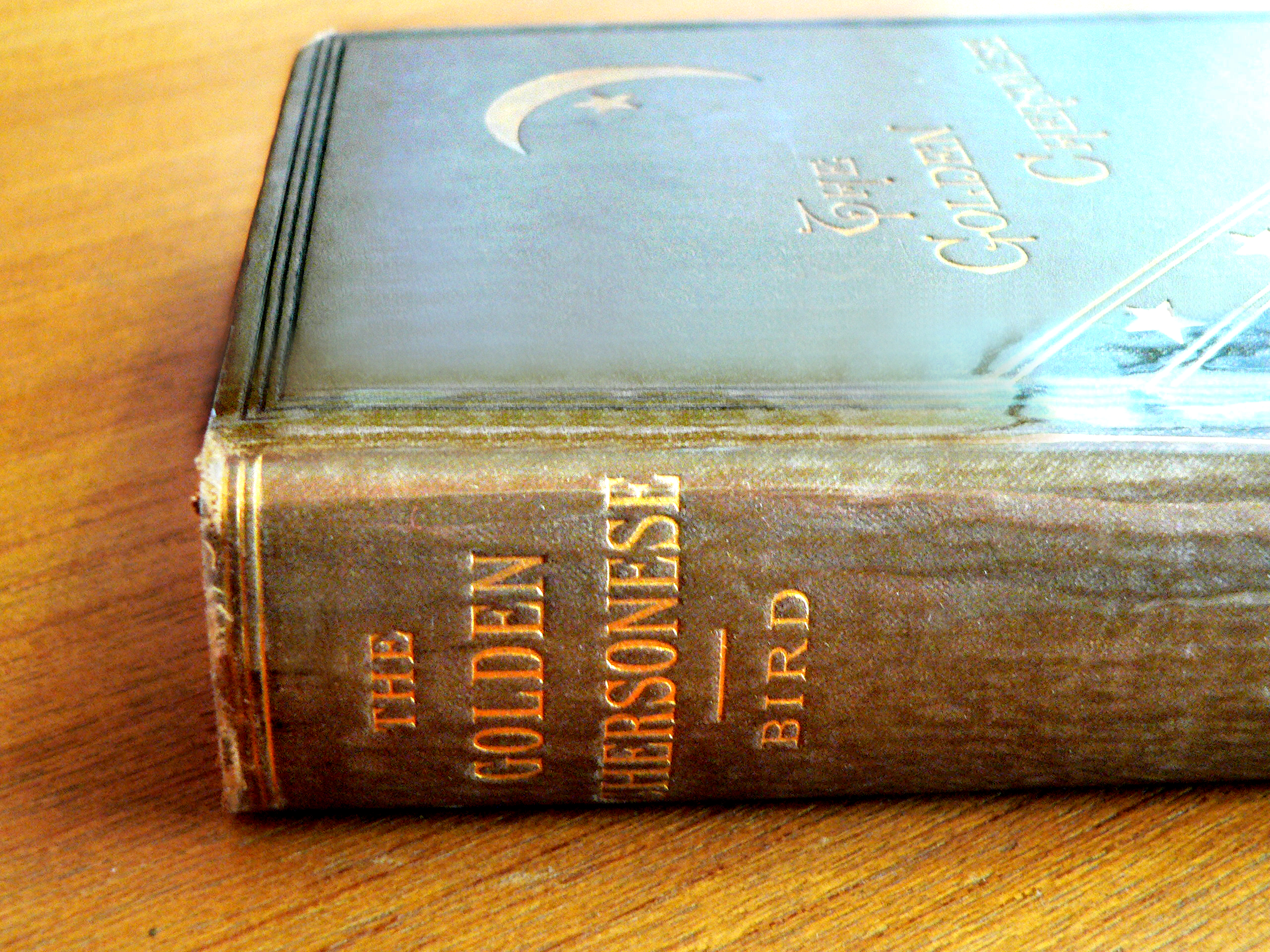

Senior Librarian Bonny Tan takes a closer look at Isabella Bird’s The Golden Chersonese (1883), which captures her travels through Malaya.

Isabella Bird: The Accidental Tourist

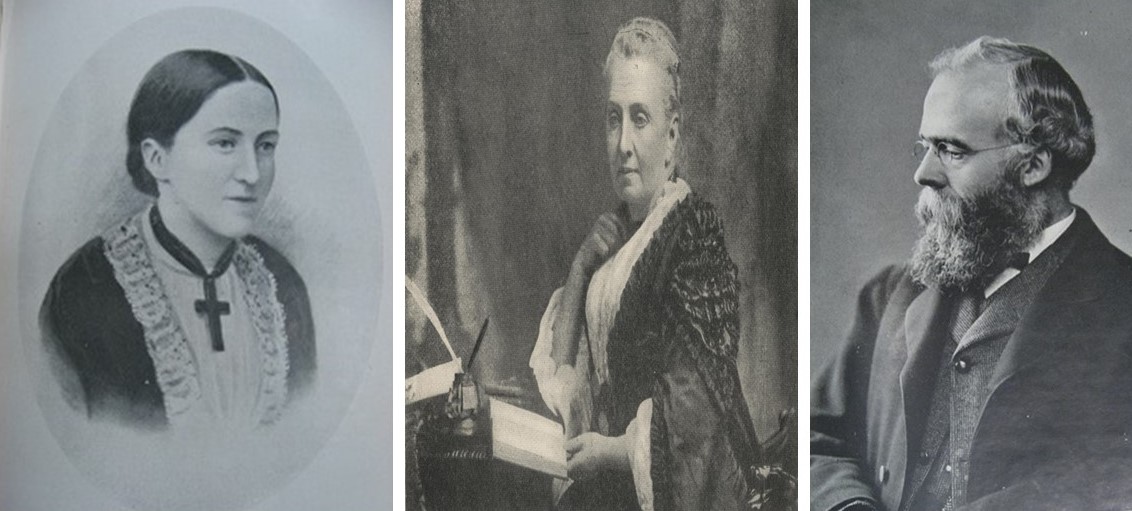

Born in 1831 in England, Isabella Bird was a celebrated travel writer known for her momentous journeys across various continents. She explored the wild unknown with the barest minimum, mostly on her own – uncommonly adventurous for a woman during the conservative Victorian era.

But travel and travel writing were not something she was naturally inclined towards. One of her obituary notices described her as “The invalid at home, the Samson abroad”,1 succinctly capturing her contradictory nature. Throughout her life, she was afflicted by ailments, with such varied symptoms that her physicians were often left in a quandary as to the diagnosis of her diseases. At 18, she had an operation to remove a lump from her spine. Thereafter, she suffered from insomnia, nausea and pain, and was often bedridden, barely able to amble out of her home. Miraculously, these sufferings were dispelled when she travelled abroad.2 In fact, some concluded that the travels served as a panacea to a constrained life at home.

Bird made her first journey at the age of 23 to North America to visit her relatives. It was made on doctor’s orders to recuperate from a bad back, though some say that it was prescribed to help her recover from lovesickness. Thereafter, the travel bug that bit her remained with her.

Bird travelled more widely in her middle age, after the death of her mother. She traversed the wide expanse of the Americas, Australia and New Zealand and through the wild lands of Asia such as China, Korea, Malaya and the Middle East. In total, she travelled for more than nine years, though there were long periods when she stayed home. Age did not mellow her venturesome spirit and she chose to explore harsher lands and take on more challenging adventures even as she entered her 70s.

Most of Bird’s early books were based on letters she had written to her only sibling, Henrietta. “In writing to my sister my first aim was accuracy, and my next to make her see what I saw” (Bird, 1883, p. viii). However, Henrietta was not just a homebound shrinking violet who merely received her adventurous sister’s letters. In fact, she was considered the more academic of the two,3 having a fluency in classical languages such as Greek and Latin.

It was Henrietta who had suggested titling Bird’s Malayan travels The Golden Chersonese, based on her knowledge of Ptolemaic history and its mention in Milton’s poems. There has been speculation that Henrietta had literally co-written much of Isabella’s earlier books.4 Bird herself had acknowledged her sister as “[her] intellect, the inspiration of all [her] literary work”.5 For The Chersonese, Bird acknowledged that “[Henrietta’s] able and careful criticism, as well as loving interest, accompanied [her] former volumes through the press” (Bird, 1883, Preface, p. vii). The Chersonese, however was Bird’s last book based on her letters to Henrietta. Henrietta died in 1880 soon after Bird returned from Malaya. Bird expressed her sense of loss, noting that the book was written “under the heavy shadow of the loss of the beloved and only sister” (ibid., Preface, p. vii), and dedicated The Chersonese to her: “To a beloved memory, this volume is earnestly and sorrowfully dedicated.” Henrietta’s death not only affected Bird emotionally, but likely also her writings. While researching for The Chersonese, Bird had appealed several times to John Murray, her publisher, to provide materials to pad up her limited knowledge on Malaya – something which Chubbuck believes Henrietta, if alive, would have invariably supplied to her sister.6

The Chersonese was Bird’s first book published after her marriage. Dr John Bishop, a learned and quiet man, who was 10 years younger than Bird, proposed to her in 1877. It is believed that Bird spurned him initially as Henrietta had fallen for him.7 It was only after the death of her sister that Bird married the doctor in 1881, purportedly fulfilling her sister’s dying wish. Bird, who was 50 years old then, dramatically wore mourning black for her wedding finery. Although it is believed that Bird was not truly in love with Dr Bishop, she mourned him deeply when he died five years into the marriage.

The Protected Malay States: Terra Incognita

The Golden Chersonese was the half-way mark of Bird’s published travelogues, which totalled nine titles. In 23 letters, Bird wrote about the British presence in Malaya, namely in the Straits Settlements – Singapore, Melaka and Penang – and in the three Protected Malay States – Perak, Selangor and Sungei Ujong8 – which had recently come under the British Residential system. Although the letters seem informal and fluid, the publication is in fact tightly structured. For example, the introduction to the book provides an overview of Malaya, its history, politics, people and landscapes. In a similar pattern, her descriptions of her travels through each Settlement or State is prefaced with a brief survey of the province before she gives her observations of and adventures in these places. However, the book is not solely about Malaya. It begins with a description of China and Bird’s journey down south, with a stopover in Saigon, Vietnam, before it elaborates on the Protected Malay States. It ends with an appendix, which describes the Residential system, the government’s opposing slavery and the various letters by Hugh Low.

Bird visited the Protected Malay States a few years after they were newly established as Protected States in 1876. Tin mining was the main industry but these States remained a wild and unexplored outpost for the British officials. In her introductory chapter, Bird noted that contemporaneous Malaya was a terra incognita: “there is no point on its mainland at which European steamers call, and the usual conception of it is a vast and malarious equatorial jungle sparsely peopled by a race of semicivilised and treacherous Mohammedans”. (ibid., p. 1) However, Bird’s survey of the land was brief and necessarily limited as it was based on a mere five-week sojourn that she had made chaperoned by British officials, travelling with official transport and lodging in the comfort of their homes.

Singapore: A Chinese City

Bird’s travels through the Malay Peninsula began in Singapore,9 a pit-stop made on her return journey from Japan in 1879. Her fame had preceded her and she was quickly invited by Cecil Clementi Smith, then Colonial Secretary, to visit the newly formed Protected Malay States. Smith probably saw an opportunity to publicise the value of the Malay States through the writings of a well-known author while Bird took this as another chance at adventure. All she needed were additional cash and necessary letters of introduction before she quickly agreed to “escape from civilization” (ibid., p. 109).

While she considered Singapore too well-known to elaborate on, Bird still gives a vivid vision of the harried, varied people in the growing port city:

Details accompany Bird’s descriptions, but they are neither dogmatic nor boring, always informative and giving flesh to a general impression. Her first biographer, Anna Stoddart, recognised Bird’s “capacity for accurate observation, her retentive memory, and her power of vivid portrayal, [that] have enabled multitudes to share her experiences and ad ventures in those lands beyond the pale which drew her ever with magnetic force” (Stoddart, 1908, p. v). Take for example her detailed description of the many tribes that made up Singapore’s populace in the late 19th century:

Indeed, her descriptions of people seem to favour the locals over her own compatriots sometimes taking a potshot at the latter’s apparent condescension towards native people and their customs. This is vividly seen in her contrasting descriptions of the local Indian women and the upper crust European ladies in the town:

The Malayans: A Woman’s Perspective

Stoddart noted that “as a traveler, Mrs Bishop’s outstanding merit is that she nearly always conquered her territories alone; that she faced the wilderness almost single-handed[ly]” (Stoddart, 1908, p. vi). That was how she travelled when she first took off to explore the Malay States. She boarded a small Chinese-owned boat, the Rainbow, to Melaka – being the only European and female traveller onboard. However, Bird was not always alone in her Malayan adventures. On much of the journey inland, she was accompanied by Babu, a native butler of sorts, the governor’s two young daughters and up to 11 other workers.

As a woman, Bird was privileged to see the more intimate side of Malayan life. She was sometimes invited to meet locals of the fairer sex and their children and she often took pains to describe the women, their dress and appearances as well as the children. In one instance, she was invited to meet a Sikh guard’s family, whom her male companions comprising officials in high leadership positions had not met before. Upon seeing the guard’s wife, Bird exclaimed in awe:

The Chersonese not only offers a peek into the communities of the newly formed Malay States, but it also gives anecdotal accounts of the people who led the Protected Malay States. In fact, “the individuals Bird’s narrative sketches are almost entirely British administrators, the empire builders engaged in the great work of creating British Malaya. They turn out to be people who were then in the process of developing extensive reputations in England, and who would, in the three decades following the publication of Bird’s book, reach enormous fame”.10 One such individual was William Edward Maxwell, whom Bird met in Perak. He was then the newly appointed Assistant Resident, but soon rose to become Acting Resident Councillor of Penang (1887–89) and Acting Governor (1891–95). She described Maxwell thus:

She then continued to describe the convivial repartee over dinner between Maxwell, Captain Walker and Major Swineburne, her travel companions, doubting that “such an argument could have been got up in moist, hot Singapore, or steamy Malacca!… That it should be possible shows what an invigorating climate this must be” (ibid., p. 286).

The Golden Chersonese: Romance or Realism?

Though some have criticised Bird for romanticising the Malay States, she did not censor her more negative impressions of the Peninsula or gloss over the challenges she faced. Indeed, she sometimes seemed to relish the more horrid experiences and observations. Such was the case when she first arrived in Selangor, where she described the squalid conditions of the village by the river: “Slime was everywhere oozing, bubbling, smelling putrid in the sun, all glimmering, shining, and iridescent, breeding fever and horrible life” (ibid., p. 243).

Even minor irritations were mentioned, as seen in her frequent complaints of incessant mosquitoes biting ceaselessly and the disappointment of sometimes expecting a meal from a host after a long day of travel, but never receiving one.11

The adverse circumstances, however, brought out Bird’s resourcefulness. She devised an innovative approach to protect herself from the heat of the sun:

When her elephant ride from Larut to Kuala Kangsar did not materialise due to some miscommunication, and she had to walk the four miles through quagmire and jungle, she recognised that she “could not have done the half of it had [she] not had [her] ‘mountain dress’ on” (ibid., p. 293). She finally meets her elephant, which had “nothing grand about him but his ugliness” (ibid., p. 298).

Even in the midst of these challenges, she was able to contemplate the uniqueness of her circumstances, sometimes describing them in such wondrous tones despite the apparent dangers and discomforts she faced. Here, she gave the context to her elephant ride:

Caught between ailment and adventure, the familiar and the strange, her countrymen and savage beasts, Bird provided her readers with a sense of feminine wonderment that colours the landscapes of the Malay States with a peculiar attractiveness.

The author wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Dr Ernest C.T. Chew, Visiting Professorial Fellow, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, in reviewing this article.

Senior Librarian

Lee Kong Chian Reference Library

National Library

REFERENCES

Anna M. Stoddart, The Life of Isabella Bird (Mrs. Bishop) (London: John Murray, 1908). (Call no. RSEA 910.924 BIR.S)

“Bibliography of Isabella Bird,” e-Asia. [e-book]. University of Oregon Library.

Christel Mouchard and Alexandra Lapierre, Women Travelers: A Century of Trailblazing Adventures, 1850–1950 (London: Thames & Hudson, 2007). (Call no. R 910.922 MOU)

Doris Jedamski, Images, Self-Images and the Perception of the Other: Women Travellers in the Malay Archipelago (England: University of Hull, Centre for South-East Asian Studies, 1995). (Call no. RSING 155.33309598 JED)

Emily Sadka, The Protected Malay States, 1874–1895 (Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press, 1968). (Call no. RSING 959.51034 SAD)

Eva-Marie Kroller, “First Impression: Rhetotical Strategies in Travel Writing by Victorian Women,” ARIEL: A Review of International English Literature 21, no. 4 (October 1990): 87–99.

Isabella Lucy Bishop, The Golden Chersonese and the Way Thither (London: John Murray, 1883). (Call no. RCLOS 959.5 BIS)

Isabella Lucy Bishop, The Golden Chersonese and the Way Thither (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1967). (Call no. RCLOS 959.5 BIS)

Isabella Lucy Bishop, The Golden Chersonese (Singapore: Monsoon Books, 2010). (Call no. RSING 915.951 BIR)

Isabella Lucy Bishop, Letters to Henrietta. (London: John Murray, 2002)

J.M. Gullick, “Isabella Bird’s Visit to Malaya: A Centenary Tribute,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 52, no. 2 (1979): 113–19. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

John Gullick, ed., “Isabella Bird: Escape from Civilisation in Malaya,” in Adventurous Women in South-East Asia: Six Lives (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1995), 196–245. (Call no. RSING 959.040922 GUL)

Lorraine Sterry, Victorian Women Travellers in Meiji Japan: Discovering a ‘New’ Land (UK: Global Oriental, 2009). (Call no. R 915.20431082 STE)

Maria Noelle Ng, Three Exotic Views of Southeast Asia: The Travel Narratives of Isabella Bird, Max Dauthendey, and Ai Wu, 1850–1930 (NY: Eastbridge, 2002). (Call no. RSEA 950.30922 NG)

Mignon Rittenhouse, Seven Women Explorers (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1964)

“Mrs Bishop,” Edinburgh Medical Journal 14 (1904): 383.

Olive Checkland, Isabella Bird and ‘A Woman’s Right To Do What She Can Do Well’ (Aberdeen: Scottish Cultural Press, 1996)

Patt Barr, A Curious Life for a Lady: The Story of Isabella Bird: A Remarkable Victorian Traveller (London: Secker & Warburg, 1984). (Call no. R 910.4 BIR.B)

Susan Morgan, Place Matters: Gendered Geography in Victorian Women’s Travel Books about Southeast Asia (N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1996). (Call no. RSING 820.9355 MOR)

“The Golden Chersonese – Its Authoress Twenty Years After,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 16 February 1897, 2. (From NewspaperSG)

NOTES

-

“Mrs Bishop,” Edinburgh Medical Journal 14 (1904): 383. ↩

-

Checkland suggests that much of her ailments were due to the drugs she imbibed during her home stay, some of which were potent drugs such as cannabis and opium. Her travels healed her as she no longer consumed these potent mixes (p. 32). Olive Checkland, Isabella Bird and ‘A Woman’s Right To Do What She Can Do Well’ (Aberdeen: Scottish Cultural Press, 1996), 32. Chubbuck believes that her actual disease was carbunculosis resulting in “infectious knobs” appearing on the spine and back. However, Chubbuck also notes that Bird’s sufferings were likely psychosomatic (pp. 5–6). ↩

-

Chubbuck, 9–10. ↩

-

Chubbuck, 13–14. Chubbuck also suggests that the sisters’ relationship was not as congenial as it seemed, but Victorian conservatism did not allow Isabella to express fully the competitiveness that was likely to have existed between them. Nevertheless, Isabella was devastated following her sister’s death from typhoid in 1880. ↩

-

From a letter by Bird to John Murray III dated 16 June 1880, as found in the John Murray Archives and cited in Chubbuck, 14. ↩

-

Chubbuck, 14. ↩

-

Chubbuck, 15. ↩

-

Though Bird describes only Sungei Ujong, this state later joined other adjoining states of Negri Sembilan. During this period however, Sungei Ujong was administered independently under the British. Emily Sadka, The Protected Malay States, 1874–1895 (Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press, 1968), 1. (Call no. RSING 959.51034 SAD) ↩

-

In fact, the first six letters of The Golden Chersonese narrates her travels down from China, through Hong Kong and Saigon, Vietnam. Her visit to Singapore is mentioned only in the seventh letter, about a quarter through the volume. ↩

-

Susan Morgan, Place Matters: Gendered Geography in Victorian Women’s Travel Books about Southeast Asia (N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1996), 152. (Call no. RSING 820.9355 MOR) ↩

-

At Permatang in Perak, for example, she was relieved to hear her host discussing breakfast. But after a bath, the visitors were expected to leave immediately, without the much desired meal. Isabella Lucy Bishop, The Golden Chersonese and the Way Thither (London: John Murray, 1883), 279–80. (Call no. RCLOS 959.5 BIS) ↩