Lived Spaces and Memories: The Indian Business Communities in Colonial Singapore

Jayati Bhattacharya offers a glimpse into the socioeconomic networks and exchanges of the Indian business community during the colonial era.

Ethnic Indian communities have had considerable influence on the sociocultural fabric and connectivity in the Southeast Asian region for many generations. However, scholarship on these communities has been far too little in relation to the continued significance of the Indic influence and diasporic interactions since very early times. The colonial discourse on the Indian community in Southeast Asia has traditionally revolved around the overwhelmingly visible labour diasporas and much less on the other sections of the Indian migrant population. In this respect, the study of the business communities is a diversion from conventional paradigms, and is also closely associated with the peoples’ movements within the complexities of economic networks.

Most voluntary transnational mobilities have been essentially associated with better economic opportunities articulated through the flows of people, capital and knowledge. The model of exchanges in labour and capital has shifted to present-day transnational global networks and interactions like remittances, commercial networks, investments or philanthropic sponsorships, apart from sociocultural bonding with the home country. In the changing trajectories of the circulation of population, money, goods and information, the dynamics of the players and those of capital may have altered, but their interactions have assumed a significant place in the socioeconomic and political exchanges in the global context. This article will offer a glimpse of these socioeconomic networks and exchanges during the colonial era which have formed a strong foundation of the present bilateral and multilateral interactions in Singapore and Southeast Asia and will continue to do so in the future.

The Indian subcontinent enjoyed global economic, political, and cultural connectivities through well-established land and sea routes. It also enjoyed political patronage and expansion by different rulers from different regions and time periods. However, Indic influence in Southeast Asian society and culture was much more significant than Indian settlements in the region. Western colonial expansions and technological innovations largely modified the prevailing dynamics channelling greater mobilities and consequent settlements within the purview of similar administrative domains. The establishment and development of a trading port in Singapore by the British, an example of the extension of the British colonial arm from the Indian subcontinent, undoubtedly facilitated the activities of the Indian merchants and traders, but this was only a part and process of continuity established long before in this part of the world. Referring to the involvement of the Indian and the Chinese in trade and finance in the Indian Ocean, Rajat Kanta Ray argues that it formed “a distinct international system that never lost its identity in the larger dominant world system of the West”.1 The existence of this indigenous system of networks and business operations is further exemplified in Claude Markovits’ work on the Sindhi merchant community.2 Takeshi Hamashita, another prominent scholar in this field, has argued that the formation and functioning of the Asian trade networks had been propelled by forces emerging from within Asia and not essentially “formed” by the impact of Western hegemony, but rather “organised” and developed by them to an extent.3 The onset of British imperialism consolidated and facilitated greater movements of goods and people to cater to their administrative, military and commercial interests.

I.

The story of Narayana Pillai stands in symbolic association with ethnic Indian businessmen arriving in Singapore with the coming of colonial expansion. When Stamford Raffles arrived in Singapore in 1819, he brought in his entourage 120 sepoys of the Bengal Native Infantry and a Bazaar Contingent of washermen, milkmen, tea-makers and domestic servants.4 He also brought Pillai, an associate in Penang since 1804,5 to Singapore to start brick kilns which were necessary for the construction work of the new settlement. Pillai is also believed to have worked in the government treasury as a chief clerk and Tamil translator.6 He became the first building contractor in Singapore and also started a cotton goods shop in Commercial Square, thus becoming a wealthy merchant. Additionally, he initiated the building of the first Hindu temple on South Bridge Road, the Sri Mariamman Temple.7

The sepoys and soldiers of the East India Company who came along with Raffles stayed behind to guard British interests. They were accompanied by a contingent of civilians to help with the daily chores, who gradually developed themselves into an organised occupational force. Other businessmen like the milkmen, both from North and South India, made good money for themselves. So did the jagas, or turbaned Sikh security guards, many of whom became part-time moneylenders and later invested their accumulated wealth in businesses. The majority of the Indians were labourers who came to the Malayan peninsula under the indentured kangany system. There were also convicts who were sent to the island and largely used as labour for the initial years of the construction of infrastructure facilities in the settlement. Most of them later assumed “self-supporter” status and settled down in the island by marrying local women.8

A familiar base of administrative and political entity, facilitated by a common British colonial master for both the Indian subcontinent and Singapore also mobilised Indian migration to the island colony. Between 1826 and 1867, the island was under the East India Company’s rule, and later under the jurisdiction of the British Raj, both of whom administered the island from Calcutta. Tan and Major point out that, to a great extent, “Singapore’s administrative and legal systems – a centralised administration in which civil power was supreme – were based on British-India lineage”.9 Interestingly, the Indian Penal Code (1860) adopted by Singapore in 1871 “still leaves its imprint on the country’s legal system”.10 The English-educated Indian migrants from the states of Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Bengal and others catered appropriately to the clerical efficiency that the British were looking for in its colonial subjects, which made them good candidates for administrative services. They were also in the professions of lawyers, doctors and civil servants, being familiar with the British colonial system for a much longer period of time, thus helping the Indians develop good relations with the British and share a convenient working relationship with them over the other migrant settlers in Singapore.

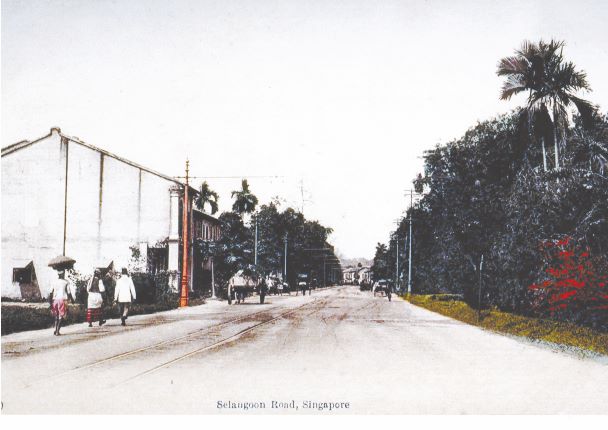

The presence of the early Indians in Melaka (Singapore then formed a part of the Malay Peninsula) dates as far back as 1413 and, according to Samuel S. Dhoraisingam, numbered around 4,000 by 1510, comprising Gujarati, Tamil and other Indian merchants.11 Those Indian merchants who were domiciled in the area soon married into the “indigenous community which included Malays, Javanese, and Bataks and some later with the wealthy Peranakan Chinese”.12 By the turn of the 20th century, many of the educated Peranakan Indians came to settle in Singapore, and like other races of their times, began to reside in enclaves across the island. They had settlements on Waterloo Street, Dalhousie Lane, Kampong Kapor, Kinta Road, Chitty Road, Rowell Road, Serangoon Road, Bencoolen Street and Selegie Road.13

In promoting entrepot trade in Singapore, Raffles initially made an effort to confront and contain Dutch expansionist ambitions, and provide a safe and free passage for British ships through the straits for their trade with China. In his own words, the purpose of establishing a colony in Singapore was “not territory but trade; a great commercial emporium and fulcrum”.14 Two-way traffic continued throughout the year between Singapore and Calcutta through the Strait of Melaka with the East India Company as well as privately owned “country ships” bringing in Indian jute, cotton, wheat and opium to Singapore and sailing back with “pepper and spices, sago, tin and silver dollars”.15 The report of the Straits Settlements Trade Commission, 1933–34, also gives us a glimpse of the extent of trading activities that was being carried out through this region in the 20th century:

Traders and merchants came in different categories and with various commercial interests. The North Indian business communities like the Sindhis, Gujaratis, Parsis and the Punjabis got involved with both the wholesale and the retail trade to provide different utilities and provisions to the migrant settlers. The Tamils (both Hindu and Muslims), the Moplahs and the Malabar Muslims formed an important part of the business population from South India, mostly trading in spices. However, the commercial class of Indian immigrants was best represented by the Chettiar community from Tamil Nadu, South India, who were mainly moneylenders. They spread their wings to different places in Southeast Asia like Myanmar, the Malayan peninsula and Thailand.

II.

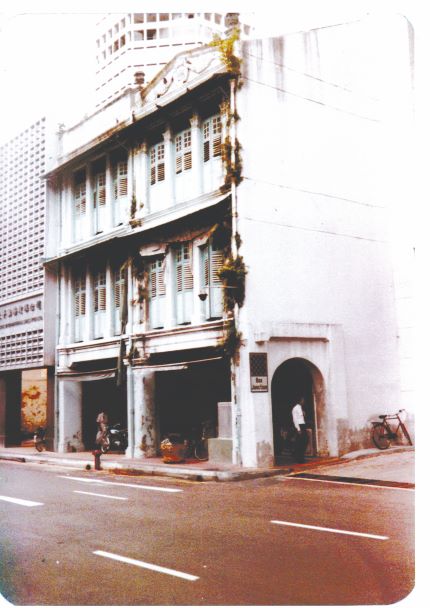

A significant characteristic of Raffles’ town planning was to create enclave structures by dividing and demarcating lived spaces on basis of ethnicities. In 1822, a committee was appointed that marked “out the quarters or departments of the several classes of population”.16 The Chulias were assigned land up the Singapore River. There were also the Mudaliars and Thirupathur Vellalars who came to Singapore from South India for various business activities. Indians also spread out to the High Street, Market Street, Arab Street, and to the Sembawang Naval Base, Tanjong Pagar and, of course, Serangoon Road. The perimeters of the different enclaves changed with time, but “each group retained an unchallenged claim to defining the identity of various areas allotted to them”.17 The areas of High Street, Market Street and Arab Street along with Collyer Quay, Cecil Street, Robinson Road and the adjacent areas formed part of the larger business district areas of Singapore.

The heterogeneity and diversity within the Indian community have brought serious challenges in the attempt to categorise them by region, caste, culture, language or profession. A. Mani18 has rightly pointed out the tendency of linguistic groupings and identification among the Indians. However, there are also other complexities involved in structuring ethnic Indians under various groups or lived spaces. Following the legacy of Raffles’ system of enclaves, we may attempt to divide them in the landscapes of the High Street, Market Street, Arab Street and Serangoon Road areas. A broader category of economic activities may also be drawn between High Street, the main centre of activities of North Indian merchants, and Serangoon Road, which was dominated by South Indian merchants, mainly Tamils. Interestingly, there have been many overlaps. Both Sindhis and the Tamils engaged in the textile business, though the Tamils traditionally dealt in retail trade, but in different spatial contexts. The Tamils were also engaged in the dairy business in a big way, and so were the men from Bihar. Similarly, spice traders were both from the Gujarati and the Tamil communities, and were situated at Malacca Street, Market Street and Chulia Street. To consider religious complexities, there could be a similarity between the Bohra Muslims from Gujarat,19 based in Arab Street and mostly dealing with textiles and spices, and the Moplahs from Kerala – otherwise known as the Malabari Muslims – also situated in Arab Street but mainly in the food and restaurant business. One of the earliest groups of traders on this island were the Chulias, or the Tamil Muslims, from the Coromandel Coast, who had established the Al-Abrar Mosque on South Bridge Road as early as around 1827.20 Different business interests and regional affiliations soon found manifestations in the formations of associations like the Sindhi Association, the Gujarati Association, the Sikh Association and several other linguistic and regional organisations. The Sindhi Merchants Association was formed in 1921, followed by the Indian Merchants Association in 1924. The latter subsequently developed into the Singapore Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industry as it is known today.

The two main areas of trading for Indian merchants during colonial times were spices and textiles. Melaka and Indonesia were the main sources for spices, and exports from Singapore included, according to oral history interviews of one of the early traders, sago flour, betel nuts, gum-benzoin, copra, long pepper, nutmegs, maize, sago seeds, tapioca seeds and rattan, which were all sent mainly to India.21 Chillies and turmeric powder were sent to Ceylon. These were the two main markets for Indian traders. Raw spices were brought to Singapore and graded before they were re-exported to other countries.22 One big name among the textile companies in the 1930s was M/s Chandulal Co., who had offices on Chulia Street in Singapore, and in Jakarta and Makasar as well.23 There were also firms that combined the business of the textiles and spices like that of Ranchoddas Purushottamdas Limited,24 which started out around 1905 and has continued for three generations. It is also considered the oldest of the Gujarati firms in Singapore.25

The textile trade was another stronghold of the Indian trading community. One of the earliest pioneers of the Indian business communities, Rajabali Jumabhoy describes these merchants as he found them in Singapore:

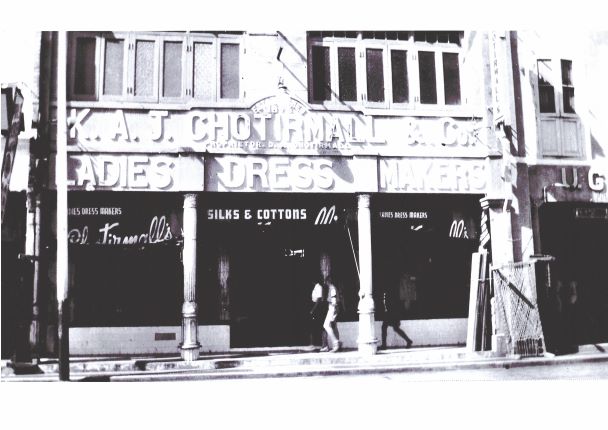

Most of the Gujarati and Sindhi communities participated in the lucrative textile business. The first known Sindhi firm in Singapore was Wassiamall Assomull, which opened its branches in 1873 along with one in Surabaya about the same time.26 Jhamatmal Gurbamall was established in the 1880s by Jhamatmal Gurbamall Melwani, who had gone to Medan from Singapore and made a large fortune in the textile business.27 The Chotirmals, Melwanis, Chanrais, Chellarams and Jashanmals were other prominent names who made their fortunes in Singapore, Hong Kong, Dubai and different other parts of the globe. Markovits pointed out: “The Sindhi merchants’ privileged connections with the big Japanese firms allowed them to steal a march on their competitors in the 1930s and to start emerging as a community of particular importance.”28 Among the Punjabis, Gian Singh Co. was a popular departmental store. The Bajaj brothers and Hardial Singh were some of the other well-known Punjabi names in business. The Parsis also had a considerable presence in Singapore. Some names like Mistri Road and Parsi Road are named after them.29

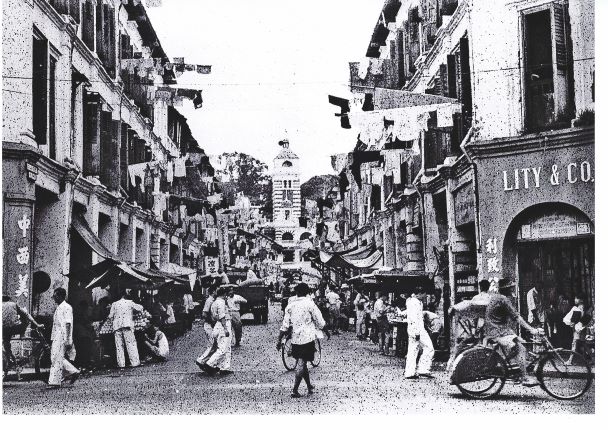

The Serangoon Road area was more or less dominated by the South Indian textile merchants, provision store owners, spice merchants, goldsmiths, florists and garland makers, petty traders, hawkers, small shop-owners, money changers and various other businessmen both big and small. Businesses in this area thrived mostly on the regular necessities of everyday Indian lifestyle. Prominent names like those of P. Govindasamy Pillai, Ramasamy Nadar and H. Somappa, who made their mark in business and in philanthropy, were based in the Serangoon Road area.

The most important of the South Indian men of commerce were the Chettiars. With their kittangis, which were simple infrastructures situated mostly around the Market Street area, they played a significant role in providing efficient moneylending services to men of all races way before the popularity of formal banking amenities appeared in the economy. They also invested a lot of their money into properties, plantations and tin investments. They mostly led a single, simple and frugal life, leaving their families back in India. They also associated their business closely with their religion. However, the Great Depression of the 1930s and the Japanese aggression during World War II dealt a severe blow to their prosperity. Many of them lost money and went back to India. The ones who returned could not bring back the past glory. Gradually, after Singapore emerged as an independent nation-state, change in moneylending laws as well as urban restructuring altered their characteristic spatial identities and market operations.

III.

The 1940s created new dynamics in migration from the Indian subcontinent. While Japanese Occupation forced many of the Indian migrants to retreat to their homeland, the Partition of the Indian subcontinent into West and East Pakistan (later Bangladesh), along with India’s independence from British domination in 1947 brought a new wave of population into Singapore and other parts of Southeast Asia. Most of the Punjabis and many Sindhi businessmen tried to reestablish themselves in Southeast Asia after losing their land and wealth in the bloodbath that followed the Partition. The Sindhis and Punjabis started arriving in large numbers, increasing the communities’ population substantially, with many trying to eke out a living at different levels of trade and business. Many of them prospered well enough to become big names, mostly in the High Street area.

The changing geopolitical dynamism with the decline of colonialism in most of Asia, and the subsequent emerging new nation-states with different political ideologies in the latter half of the 20th century, brought economic complexities that ushered in a transition in the composition and components of trade among the ethnic Indian business communities. Post-1965 Singapore brought forth a new trajectory of economic development in the city-state and renewed multicultural interactions. New domestic and foreign policies, rapid industrialisation and urban restructuring brought about changes in architecture of lived spaces and different dynamics in socioeconomic interactions. The visual images of both High Street and Market Street changed with the replacement of the shophouse structures by modern buildings. Nonetheless, the Serangoon Road area still maintains most of its old-world charm, though it had come a long way from being identified with a cattle-rearing area.

The spatial Indian identity and influence in colonial Singapore’s landscape remained a part of colonial Singapore’s heritage in its multi-ethnic fabric. Though a minority, the Indians remain an important section of the population and continue to play a significant part in the city-state’s socioeconomic expansion in its subsequent years of development.

Visiting Research Fellow

Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies

NOTES

-

Rajat Kanta Ray, “Asian Capital in the Age of European Domination: The Rise of the Bazaar, 1800–1914,” Modern Asian Studies 29(3) (July 1995): 553–54. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website). ↩

-

Claude Markovits, The Global World of Indian Merchants, 1750–1947: Traders of Sind From Bukhara to Panama (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000). (Call no. RBUS 382.095491 MAR) ↩

-

Takeshi Hamashita, “‘Rethinking Historical Network in Asia’ in the Workshop on Asian Business Networks, 31–3–1998 to 2–4–1998,” organized by Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, National University of Singapore and Institute of Oriental Culture, Tokyo University. ↩

-

They were locally known as Bengalees possibly for their association with the Bengal Native Infantry. Some later left the garrison to become civilian migrants in the new land. Brij V. Lal, Peter Reeves and Rajesh Rai, eds., The Encyclopedia of the Indian Diaspora (Singapore: Editions Didier Millet in association with National University of Singapore, 2006), 176. (Call no. RSING 909.0491411003 ENC) ↩

-

Robert Godfrey and Samuel Dhoraisingam, eds., Passage of Indians, 1923–2003 (Singapore: Singapore Indian Association, 2003), 8. (Call no. RSING q369.25957 NET) ↩

-

M. Sangaralingam, “The Role of the Tamils in the Development of Singapore,” in Cinkappuril Namatu Varalaru: Pattavatu Cinkappurt Tamil Ilaiyar Manattu Ayvatankal [Our History in Singapore: 10th Singapore Tamil Youth Conference Proceedings], ed. A. Veeramani (Cinkappur: Cinkappur Tamil Ilaiyar Manram, 1999). (Call no. Tamil YPRSING 305.894811 SIN) ↩

-

Godfrey and Dhoraisingam, Passage of Indians, 8–9. ↩

-

Lal, Reeves and Rai, Encyclopedia of the Indian Diaspora, 45–46. ↩

-

Tan Tai Yong and Andrew Major, “India and Indians in the Making of Singapore,” in Singapore-India Relations: A Primer, ed. Yong Mun Cheong and V.V. Bhanoji Rao (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1995), 5. (Call no. RSING 337.5957054 SIN) ↩

-

Tan and Major, “India and Indians in the Making of Singapore,” 5. ↩

-

Samuel S. Dhoraisingam, Peranakan Indians of Singapore and Melaka, Indian Babas and Nonyas – Chitty Melaka (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2006), 4. (Call no. RSING 305.8950595 SAM) ↩

-

Dhoraisingam, Peranakan Indians of Singapore and Melaka, 4. ↩

-

Dhoraisingam, Peranakan Indians of Singapore and Melaka, 17–18. ↩

-

Colin Anderson, Simon Cowling and Russell Springham, eds., Singapore 30: A Portfolio of Singapore’s Leading Companies (Singapore: Springham Anderson Design Pte Ltd, 1995), 7. (Call no. RSING 338.76095957 AND) ↩

-

Roderick Maclean, A Pattern of Change: The Singapore International Chamber of Commerce from 1837 (Singapore: Singapore International Chamber of Commerce, 2000), 14. (Call no. RSING q380.10605957 MAC) ↩

-

Walter Makepeace et al, ibid, 345. See The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, vol. V, no. 1, January 1851 (From BookSG); J. R. Logan, The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, Vol. VIII, 1854. ↩

-

Sharon Siddique and Nirmala Puru Shotam, Singapore’s Little India: Past, Present and Future (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1982), 7. (Call no. RSING 305.89141105957 SID) ↩

-

A. Mani, “Indians in Singapore Society,” in Indian Communities in Southeast Asia, ed. K.S. Sandhu and A. Mani (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2006). (Call no. RSING 305.891411059 IND) ↩

-

The three most common sects of the Gujarati Muslim migrants were the Bohras, Khojas and the Memons. Bohras were perhaps the largest in number. ↩

-

‘Al-Abrar’ or ‘Koochoo Pally’ means a small mosque in Tamil. The mosque has been gazetted as a national monument in 1974. For further reference, see Norman Edwards and Peter Keys, Singapore: A Guide to Buildings, Streets, Places (Singapore: Times Books International, 1988). (Call no. RSING 915.957 EDW) ↩

-

Kantilal Jamnadas Shah, oral history interview by Lim How Seng, 21 September 1981, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 2 of 8, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000094), 11–21. ↩

-

Kantilal Jamnadas Shah, oral history interview, 21 Sep 1981, 11–21. ↩

-

Kantilal Jamnadas Shah, oral history interview, 21 Sep 1981, 11–21; Kantilal Jamnadas Shah, oral history interview by Lim How Seng, 21 September 1981, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 3 of 8, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000094), 23–31. ↩

-

D.G. Shah, oral history recordings, reel 1. ↩

-

“About Us – History,” Singapore Gujarati Society, 2021, https://sgs.my.site.com/s/about. ↩

-

A. Mani, “Indians in Jakarta,” in Indian Communities in Southeast Asia, ed. K.S. Sandhu & A. Mani (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 98–130. (Call no. RSING 305.891411059 IND) ↩

-

Prakash Bharadwaj, Sindhis Through the Ages: Far-East & South-East Asian Countries (Hong Kong: World Wide Publishing Company, 1988), 367. ↩

-

Markovits, Global World of Indian Merchants, 149. ↩

-

For further details on these businessmen, refer to Jayati Bhattacharya, Beyond the Myth: Indian Business Communities in Singapore (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2011). (Call no. RSING 338.708991405957 BHA) ↩