A Work of Many Hands: The First Japanese Translation of John’s Gospel and His Epistles

The first Japanese translation of John’s Gospel and His Epistles was printed at a small printing press in 1837 in Singapore. Professor Emeritus Sachiko Tanaka and Senior Associate Irene Lim trace the path it took for this book to be produced.

The first Japanese translation of John’s Gospel and His Epistles was printed in 1837 in a modest printing press in Singapore. This was located at the corner of Bras Basah Road and North Bridge Road where the Raffles Hotel stands today. Tracing the production of this pioneering work – its translation, typesetting, woodcutting and eventual printing – takes us through 19th-century Japan, China, US, England and its colony of Singapore. It required the resourcefulness and passion of individuals, persevering support and resources of mission societies, and an open socio-political climate in host countries to enable the completion of the work.

The essay begins in 19th-century Japan where a Japanese crew that had set sail for Edo (now known as Tokyo) got shipwrecked and three surviving sailors finally washed up in America. The following section details how the earnest efforts of American and English missionaries to repatriate the sailors were met with resolute hostility from a Japan which practised a closed-door policy, forcing them to live estranged in a country and culture vastly different from theirs. Meanwhile in Macao (now known as Macau, the ex-Portuguese colony near Hong Kong), the Japanese worked with a German missionary in his ambitious attempt to translate John’s Gospel and His Epistles into Japanese. Printing the manuscript posed another challenge, for the printing capabilities of missionary societies were in their nascent stage in the first half of the 19th century (Proudfoot, 1994, p. 9).

Since China then was hostile to foreigners and missionaries, the manuscript and types were sent to Singapore, where the more open socio-political climate and available printing and press capabilities enabled its printing. In Singapore, Chinese engravers who had no knowledge of Japanese were tasked to produce the woodcuts for printing the translation. With funding from an American mission society, the translation was finally printed, having by then utilised the competences and resources of several individuals of varying affiliations, and who were located in different cities.

Unexpected Opportunity: Stranded Japanese Sailors Help Translate John’s Gospel and His Epistles

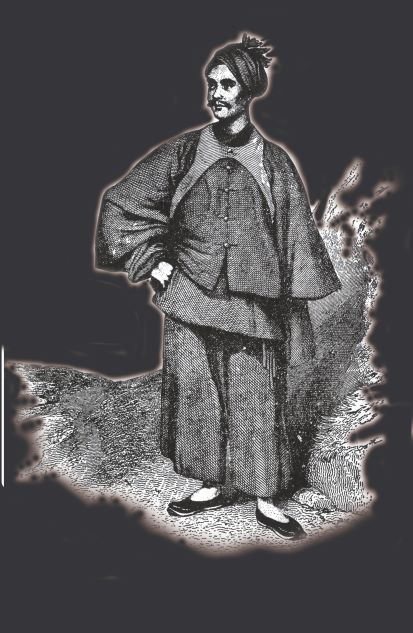

Japan adopted a closed-door policy from 1638 to 1854. The opportunity for foreigners to enter Japan or interact with Japanese culture in the early 19th century was rare, if any. To have the Bible translated into Japanese would therefore have been an insurmountable task.1 Yet, it was an ambition that Dr Karl Gützlaff (1803–1851), a German missionary, dared to embrace.

In November 1832, the Hojunmaru2 (literally “treasure-followship”) had set sail for Edo from Toba Port, one of the major ports between Osaka and Edo, carrying freshly harvested rice, pottery and other consumer goods in time for the new year. Most of its 14-member crew was from a small fishing village called Onoura, located not far from Toba across the Ise Bay on the Pacific Ocean coast. After several days at sea, the Hojunmaru was shipwrecked after encountering a fierce storm. Incredibly, the crew drifted east along the Japan Current and found land only after 14 months. By then the crew had been reduced to three (Haruna, 1879, pp. 29–33).

Sometime between the end of 1833 and the early months of 1834, the three surviving crew members were washed ashore the northwest coast of the American continent, near Cape Alva, on the Olympic Peninsula in the present state of Washington (Mihama et al., 2006, p. 3). They were Otokichi (the youngest, about 17 years old), Kyukichi (18 years old) and Iwakichi (an experienced helmsman around 30 years old) (see note 8, Haruna, 1979, p. 255). They were discovered by and lived with the Makah tribe3 in what is now known as a “long house” until May 1834, when John McLoughlin, chief factor, trader and administrator of the then Oregon Country of Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC)4 at Fort Vancouver, bought them at a high price from the tribe (Rich, 1941, p. 122).

At Fort Vancouver, the three Japanese regained their health under the care of McLoughlin , who was also a medical doctor. They found themselves surrounded by strange European faces and unfamiliar customs, and were sent to a school for the children of company workers and local methis (mixed-blood children of white Europeans and native Indians). Methodist missionary Cyrus Shepard reported to the Boston Office of the Methodist Episcopal Church on 10 January 1835, “I have also had three Japanese under instruction… While in school, they were remarkably studious, and made very rapid improvement.”5 In Japan, the three Japanese would have attended a local temple school that taught katakana6 and the use of the abacus. They would also have been taught that speaking to foreigners was forbidden and that listening to a Christian message would have meant a certain death in those days. At Fort Vancouver, the three Japanese did all of that and even joined in at mealtime prayers for they saw kindness in those who gave them shelter.

McLoughlin, as chief administrator of the British Hudson’s Bay Company, cherished the hope that Japan may open its doors to Britain – Vancouver was then still a British colony – by sending the shipwrecked Japanese back to their home. So, he put them on their company ship, the Eagle (a 194-ton brigantine captained by W. Darby), which left the Columbia River on 25 November 1834 via Honolulu and arrived at London in the beginning of June 1835.7 She anchored on the Thames and the three Japanese were taken to see the great city of London, thus becoming the first recorded Japanese to walk the streets of London. This was sometime between 6 June and 13 June, and they left for Macao on the General Palmer on 12 or 13 June.8

The six-month journey via the Cape of Good Hope brought the three Japanese to Macao in late December 1835. In Macao, they were put under the care of Gützlaff, a German missionary who was working as a Chinese interpreter of the British Board of Trade. Gützlaff had been in Batavia (Jakarta) from 1827, and while living with W.H. Medhurst, a missionary of the London Missionary Society (LMS), he first learned Chinese and Malay. However, when he saw Medhurst’s English and Japanese Dictionary published in 1830,9 Gützlaff, being a natural linguist, became very interested in learning Japanese.

A shipwreck that left three Japanese stranded and severely homesick in a foreign land turned out to be a golden opportunity for a pioneering collaborative work. Gützlaff enlisted the help of the three Japanese in translating John’s Gospel and His Epistles into Japanese. One of his letters from Macao (dated November 1836) tells of his daily schedule: 7–9 am, Chinese translation of the Old Testament; 9:30 am–noon, Japanese translation of the New Testament with the help of two/three Japanese; 12–1 pm, examination and correction of the above translation, etc. On Sundays, he conducted a Japanese service from noon to 1 pm.10

Gützlaff also wrote to the American Bible Society in January 1837 detailing how these hours were spent: “Whilst I have the original text before me, I translate sentence by sentence asking my native assistants how they understand this; and after having ascertained that they comprehend me, they put the phraseology into good Japanese without changing the sense. One of them writes this down, and we revise it afterwards jointly” (ABS History, Essay #16, Part III-G, Hills, date unknown, G-2, G-3). Admittedly, it was a rudimentary attempt at translation by modern-day standards. The three Japanese must have tried hard to understand Gützlaff’s English and the new concepts of the Gospel message, and thereafter find suitable Japanese expressions for these with their limited vocabulary. After seven to eight months of intense interactions, Gützlaff and the three Japanese completed the manuscript of the Japanese translation of John’s Gospel and His Epistles.

Denied a Homeward Passage: The Morrison Incident of 183711

There were exchanges of letters between China and the London Foreign Office on the return of the three castaways from Macao to Japan. One letter dated 16 January 1836, from Robinson, Chief Superintendent of Trade in China, included a note in kanji (with katakana reading alongside and English translation added by Gützlaff) that gives the date, the port of departure in Japan, the name of the ship owner, crew size, and a note signed by Iwakichi, Kyukichi and Otokichi expressing earnest desire to return to Japan (Beasley, 1995, p. 23).

In March 1837, another group of four shipwrecked men from Kyushu in southernmost part of Japan, were brought to Gützlaff. Arrangements were made for the Morrison (instead of waiting for the delayed Himmaleh) to take all the seven castaways back to Japan and at the same time ascertain if Japan was ready to open its doors to foreign trade and Christian evangelism. As it was meant to be a peaceful visit, they removed all the guns from the ship. On the evening of 3 July 1837, a group of 38 people (Mr and Mrs King of the Olyphant, and their maid, S.W. Williams, medical missionary Parker, Captain D. Ingersoll, seven Japanese and crew members came on board (with Gützlaff joining them at Okinawa). After giving a prayer of thanks to God, the ship left Macao for Edo the next morning.

The trip ended in failure. The Morrison, which was flying an American flag and a white flag as a sign of peace, was fired at by the Japanese government twice: once at Edo Bay on 31 July and another time at Kagoshima Bay on 12 August. No one on the ship knew about the Tokugawa government’s order, active since 1825, that all foreign ships entering Japanese waters would be fired at no matter what. The incident stirred up heated arguments among Japanese government officials and scholars as to whether the policy of seclusion was necessary. The order, however, was not so strictly enforced from 1842 when Japan learned of what had happened to China at the end of the Opium War (1839–42).12

The seven Japanese, who felt that they had literally been cast away from their homeland, began to find ways of supporting themselves – two worked for the British Office under Gützlaff, two or three taught Japanese or helped at Williams’ press13 etc. Williams subsequently entered Japan as interpreter for Commodore Perry’s trip which opened the doors of Japan by concluding the Treaty of Peace and Amity between the United States and the Empire of Japan signed 31 March 1854.14 Otokichi, subsequently baptised as John Matthew Ottoson, also entered Japan as interpreter for Sir James Stirling,15 who concluded the first Anglo-Japanese Convention signed 14 October 1854. At the time, Otokichi was working as the gatekeeper for Dent, Beale and Co. in Shanghai and later moved to Singapore in 1862. He was granted British citizenship on 20 December 186416 and died at Arthur’s Seat in Siglap on 18 January 1867 at the age of 50 (Anon., 1867). He was buried the following day at Bukit Timah Christian Cemetery. His remains were subsequently moved to the Japanese Cemetery in Hougang (Leong, 2005, p. 54). Part of his ashes were brought back to Onoura in 2005 and buried at the old tomb for the Hojunmaru crew.17

Unwelcome Outreach: Redeployment of American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions out of China, and a Japanese Typeset from America

Evangelising in China was the goal of many European missionary societies in the early 19th century, and the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) was one such society (Lee, 1989, p. 4). When the Manchu government issued explicit opposition to Christianity and foreign missionaries (Byrd, 1970, p. 61), many missionaries who had set their hearts on China established temporary staging posts in Southeast Asia where the political climate was relatively more open and their resident Chinese populations sizable (Milne, 1820).

A popular way of proselytising was to distribute tracts on Christian literature, which explains the efforts of mission societies in promoting literacy and expanding the use of printing presses (Proudfoot, 1994, p. 13; Teo, 2008, p. 12). Elijah C. Bridgman (1801–61) was the first Protestant missionary sent to China by the ABCFM, arriving in Canton in February 1830. He established a mission press and began the publication of an English monthly magazine, The Chinese Repository, in May 1832 with the aim “to review foreign books on China, with a view to notice the changes that have occurred, and how and when they were brought about, and to distinguish… between what is, and what is not” (Bridgman, 1832, Vol. 1, No. 1, p. 2).18

In October 1833, two missionaries, Ira Tracy (1806–41) and Samuel W. Williams (1812–84), arrived in Canton and were greeted by a hostile community where the Chinese authorities degraded “every ‘barbarian’ who ventured to their territory” including those who wanted to learn Chinese and/or spread Christianity (Williams, 1972, pp. 54–55). As they were walking around the walled city of Canton one day, a group of Chinese physically attacked and robbed them (ibid., p. 68). Finding it impossible to print any books or tracts in Chinese, ABCFM transferred their Chinese xylographic printing and 10 native workmen from Canton to Singapore in 1834 (Anon, 1837, p. 95) and “since March 1834, no attempts at getting books printed by Chinese in Canton have been made” (ibid., pp. 460–463).

The ABCFM also transferred Tracy from Canton to Singapore for him to take charge of the Singapore station in July 1834 (Anon, 1835, p. 17). Williams, however, being a trained printer, stayed on in Canton with Bridgman and wrote articles and did editorial work for The Chinese Repository. However, in December 1835, the mission decided to transfer Williams and his office to Macao (Williams, 1972, p. 80). In Macao, Williams wrote to his father on 25 June 1836 that Kyukichi “was sent on an errand to me to-day, and finding that he could talk broken English, I asked him as many questions as I could think up”. He continued to tell him in some detail the story of the shipwreck as recounted by Kyukichi (ibid., pp. 83–84). Gützlaff must have sent Kyukichi to Williams with parts of the translated work – probably one or two chapters each time – so that Williams could make a block copy of it. As no Japanese font existed then, Williams would have had to make a copy of the manuscript using brush on thin paper. The block cutters would then trace the written block print and cut one word at a time. It was several years later, between 1844 and 1848, that Williams had a set of Japanese katakana type made in New York, and brought it back to Macao.19

Taking the Manuscript to Print: Printing Capabilities of the Mission Press in Singapore

In Singapore, printing initiatives first began with the arrival of the LMS soon after its founding in 1819. The LMS was granted the lease EIC Lot 215 (located at the corner of Bras Basah Road and North Bridge Road where Raffles Hotel stands today) to set up a missionary chapel in 1819 (Byrd, 1970, p. 13; see Plan of Town of Singapore, 1854). In 1823, the LMS established a modest printing press, initially located on the Mission Chapel grounds, with permission from Stamford Raffles who needed its services to run his administration (Byrd, 1970, p. 13; O’Sullivan, 1984, p. 77).

It was Claudius Henry Thomsen (1782–1890), a missionary with the Malay missions of the LMS, who brought with him a small press and two workmen when he moved from Melaka to Singapore in 1822. The press consisted of a small quantity of worn-out Malay types and old English types that could produce a four-page print. It was not able to handle regular book-printing. The two workmen composed in English and Malay. One did type-cutting and the other bookbinding (Byrd, 1970, p. 13; O’Sullivan, 1974, p. 73). Thomsen also had the help of a missionary colleague, Samuel Milton (1788–1849), who had come to Singapore earlier in October 1819 (Milne, 1820, p. 289).

While the men corresponded with the LMS in London on their printing and press needs, they also had to rely heavily on their own resourcefulness.

Thomsen subsequently built a very extensive printing works, whose mortgagor was the Anglican chaplain in Singapore, the Rev. Robert Burn (1799–1833). It comprised “three buildings, two brick ones with eight rooms each for the workmen and stores, and another wood and attap building for the printing works” (O’Sullivan, 1974, p. 79). Thomsen subsequently sold the printing press and some land to the ABCFM in 1834 before returning to England. As mentioned earlier, Tracy arrived in Singapore from Canton to manage the press under the ABCFM. It comprised “two presses, a fount of Roman type, two founts of Malay, one of Arabic, two of Javanese, one of Siamese, and one of Bugis; and apparatus for casting types for all these languages, and for book-binding” (Anon, 1835, p. 17).

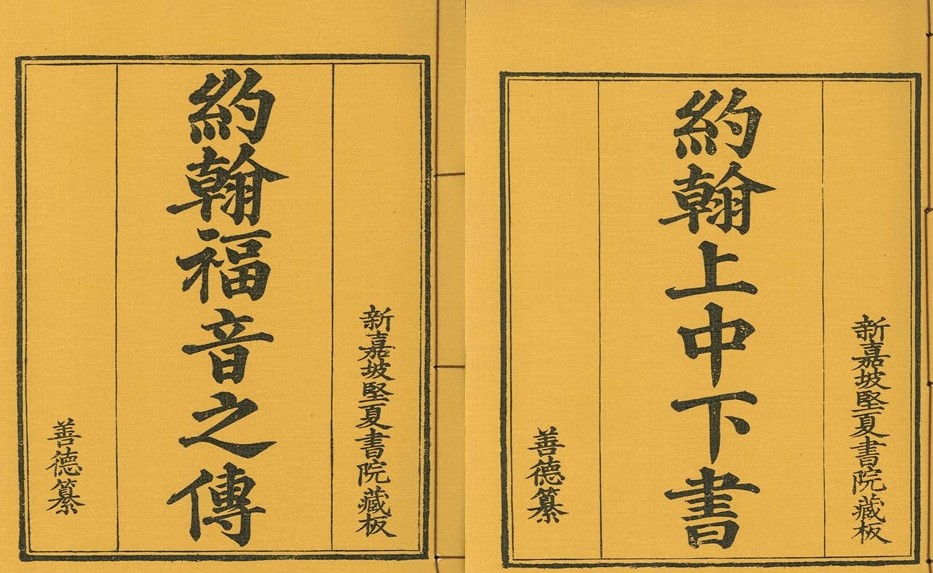

This may be regarded as the founding of the ABCFM mission in Singapore. Printing in Chinese was carried out by xylographic printing, with the Mission Press known in Chinese as 新嘉坡:堅夏書院蔵板. Alfred North (1807– 66), having been trained as a printer by S.W. Williams’ father in America, was sent to Singapore in 1836 to supervise the mission press. In March 1836, Bridgman was able to announce that “a full printing establishment at Singapore had been purchased, consisted of two presses, of fonts of English, Arabic, Bugis, and Siamese type, and of other necessary equipment” (Latourette, 1917, p. 105, Note 120, quoting Bridgman’s letter to the Board on 1 March 1836).

Given the printing capabilities available in Singapore, Bridgman therefore advised Gützlaff to send his manuscript there to be cut in wood. Thus, on 3 December 1836, even before the seven Japanese castaways embarked on their homeward journey on the Morrison, Gützlaff had sent the Japanese manuscript, together with his Chinese translation of the entire New Testament, Genesis and Exodus, to Singapore on the Himmaleh, an American merchant/Gospel ship owned by Olyphant & Co. The ship left Macao for Celebes (now Sulawesi, a part of Indonesia) and Borneo island via Singapore and was expected to return by May or June with the printed books.20

Besides the limited printing capabilities, the language competence of the wood-carvers posed another challenge. The Chinese wood-carvers at the Mission Press had no knowledge of Japanese and thus produced the woodcuts for the manuscript based on the visual image of the Japanese characters. This is substantiated by the fact that the printed manuscript shows mistakes that would not have been made by one who had simple knowledge of Japanese. For example, ツクル (to make) was cut as ツケル, and ヒトツモ (even one) was cut as ヒトツ七.

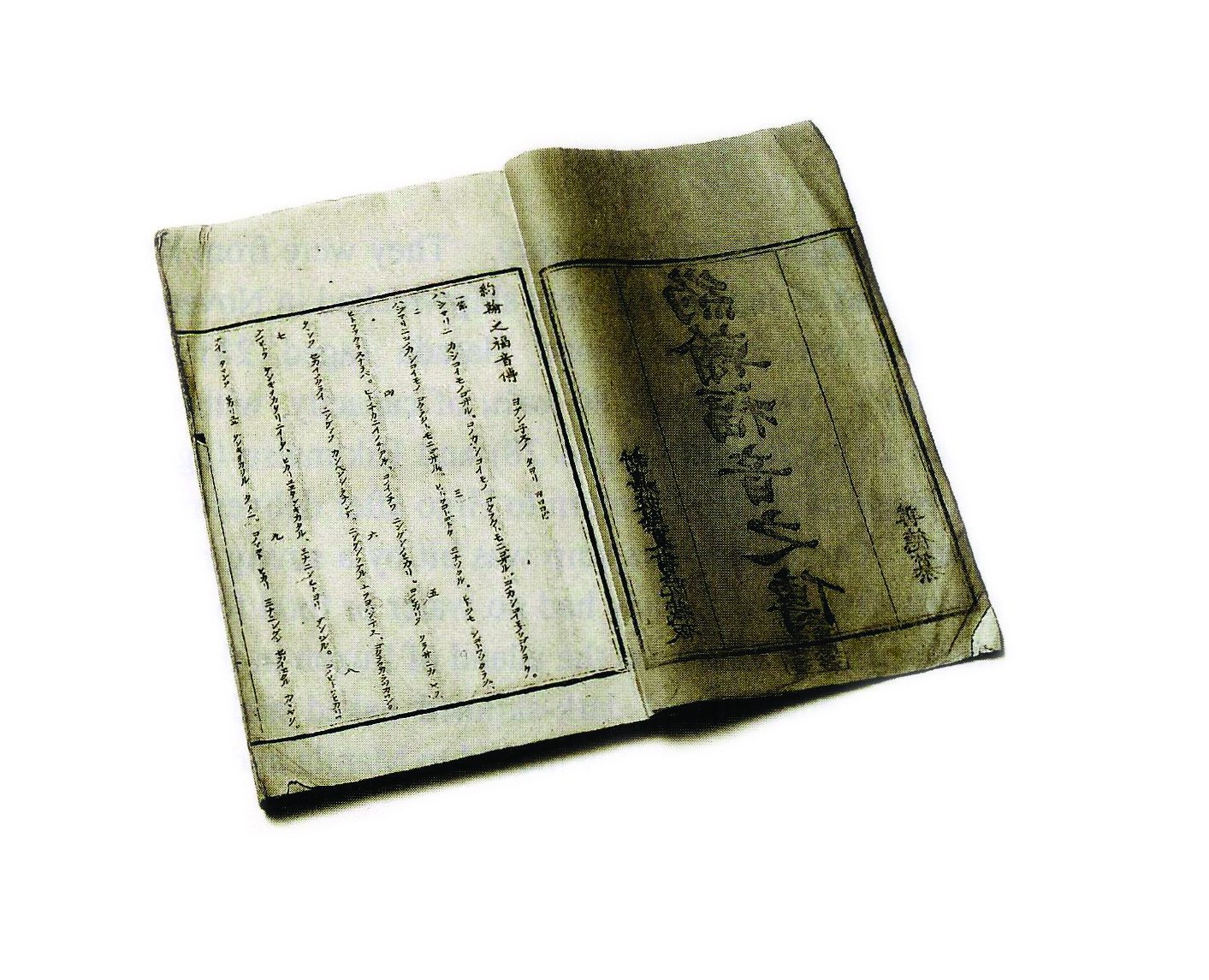

The Missionary Herald (Anon, 1838, p. 419) lists books and tracts printed in Chinese including the oldest surviving Japanese translation of the Gospel and Epistles of John by Gützlaff in his Chinese name: 約翰福音之傳 (120 pages, printed on Chinese paper) and 約翰上中下書 (20 pages), by 善徳纂 at 新嘉坡堅夏書院蔵板.21 The entire cost of block-cutting, printing and binding was recorded as $352.82, and was paid for by the American Bible Society from the funds handled by S.W. Williams. In total, 1,525 copies of John’s Gospel and His Epistles and about 1,400 copies of his letters were printed and carried by the Himmaleh to Macao and unloaded on the small island of Lintin on 15 August 1837, while the Morrison was sailing back from Japan with the disheartened Japanese seamen on board (Akiyama, 2006, pp. 295–297). Though the books themselves do not identify the year of publication, some writings by the owners of the original copies suggest that they were printed in May 1837 (ibid., pp. 311–314), though there are some traces of minor revisions made twice since then, probably by November 1839 (ibid., p. 320) when many of the missionaries were moved from Singapore to China.

With the opening up of China in 1843, the ABCFM closed its Singapore station and gave the land and press to the LMS. The press was managed by Benjamin Peach Keasberry (1805–75), an LMS missionary who continued to serve in Singapore even after the LMS closed its Singapore station in 1846. After Keasberry’s death, the press was sold to John Fraser and David Chalmers Neave in 1879, who later absorbed the press into their aerated-water company, Singapore and Straits Aerated Water Co., in 1883 (Makepeace, 1908, p. 265; Anon, 1931, p. 14).

Conclusion

Only 16 copies of the Japanese translation of John’s Gospel are known to exist around the world – in Boston, London, Paris, Tokyo, etc.22 Tracing the production of these has allowed us a glimpse into the socio-political conditions of several countries, and the resourcefulness and determination of Gützlaff and his contemporary missionaries in managing the resources available to them in order to achieve their goals.

How does the 19th-century pioneering translation impact us today? It is important in several ways: Christians can learn from it how new concepts were coined in the words that could be understood by everyone without much schooling; scholars of the Japanese language can learn from it how the language has changed (its pronunciation, vocabulary and grammar); those who study the Edo period can learn from it because it reflects the social customs and class distinctions of the era. The translation has been reprinted five times – by Nagasaki Publishing Co. in 1941 during World War II and by Shinkyo Press (which incorporated Nagasaki Press) in 1976, 2000, 2009 and 2011, with each reprint carrying an accompanying commentary revised with new findings by N. Akiyama.

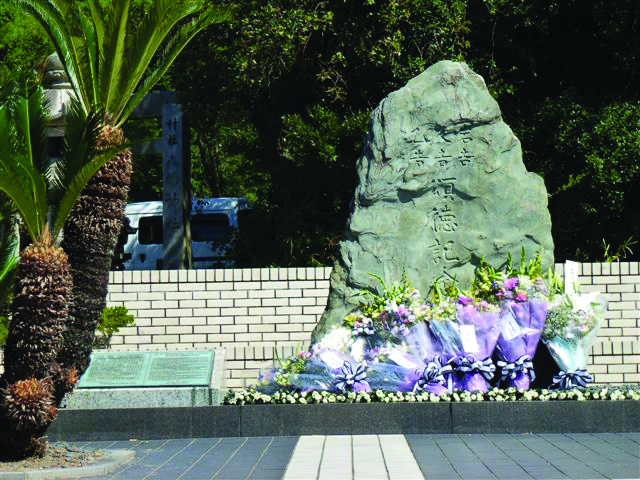

On 6 October 2011, 120 people gathered for the 50th Memorial Service commemorating the founding of the Stone Monument (on which the names of Otokichi, Kyukichi and Iwakichi are carved) for the first Japanese translation of the Bible. The monument stands by the beach, facing west towards Ise Bay and the Pacific Ocean. Around the time of the commemoration, a copy of the reprint was sent to the National Library Board, Singapore, to be deposited for posterity.

Sachiko Tanaka

Sachiko TanakaProfessor Emeritus

Sugiyama Jogakuen University

Irene Lim

Irene LimSenior Associate

NL Heritage, National Library Board

REFERENCES

Aichi Mihama & Friends of Otokichi Society. (Eds.). (2002, 2006). Otokichi no Ashiato o Otte – Kusanone Katsudo no 15nen [Footprints of Otokichi – 15 years of grassroots activities]. Mihama: Town of Mihama.

Aihara, R. (1954). Tenpo Hachinen Beisen Morrison-gou Torai no Kenkyu [A study of American Ship Morrison visiting to Japan in 1837]. Tokyo: Yajin-sha.

Akiyama, N. (2006). Hon no Hanashi – Meijiki no Kirisutokyo-sho [A story of books – Christian books in the Meihi Era]. Tokyo: Shinkyo Publishing Co.

Beasley, W.G. (1995). Great Britain and the opening of Japan 1834–1858. Kent: Japan Library. (First published in 1951 by Luzac & Co.)

Byrd, C.H. (1970). Early printing in the Straits Settlement, 1806–1858. Singapore: National Library. (Call no.: RCLOS 686.2095957 BYR)

Haruna, A. (1979). Nippon Otokichi Hyoryuki [A story of Otokichi’s drift]. Tokyo: Shobunsha. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Hawks, F. (Ed.). (1856). Narrative of the expedition of an American squadron to the China seas and Japan, performed in the years 1852, 1853 and 1854, under the command of Commodore M.C. Perry, United States navy, by order of the Government of the United States. Washington: Beverley Tucker, Senate Printer. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Hills, M.T. (1965). ABS history, essay # 16, Part III-G, Text & Translation. G-2 [Gützlaff’s letter to ABS in January, 1837) and G-3 (Williams’ letter 31 January 1843, reporting how the money was used).

Hudson’s Bay Company Archives. (1973). C. 4/1, Fols. 15d.26 & C. 7/132. Winnipeg: Archives of Manitoba.

King, C.W., & Lay, G.T. (1839). The Claims of Japan and Malaysia upon Christendom, exhibited in notes of voyages made in 1837 from Canton, in the ship Morrison and the Brig Himmaleh under the direction of the owners (2 vols.). New York: E. French. (Call no.: RRARE 266.0237305 CLA)

Latourette, K.S. (1917). The history of early relations between the United States and China 1784–1844. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lee, G.B. (1989). Pages from yesteryear: A look at the printed works of Singapore, 1819–1959. Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society. (Call no.: RSING 070.5095957 PAG)

Leong, F.M. (2005). The career of Otokichi. Singapore: Heritage Committee, Japanese Association Singapore. (Call no.: RSING q959.5703092 LEO)

Lim, I. (2008). Mission Press. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website.

Milne, W.C. (1820). Retrospect of the first ten years of the Protestant mission to China. (now, in connection with the Malay, denominated, the Ultra-Ganges missions); Accompanied with miscellaneous remarks on the literature, history, and mythology of China, & c. Malacca: Anglo-Chinese Press. Retrieved from BookSG.

Ohmori, J., Higashida, M., & Tanaka, S. (2007). Global drifters. Nagoya: The Otokichi Association.

O’Sullivan, l.L. (1984). The London Missionary Society: A written record of missionaries and printing presses in the Straits Settlements, 1815–1847. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 57 (2) (247), 61–104. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Parker, P. (1838, June). Journal of Mr Parker on a voyage to Japan. Missionary Herald, 34 (6), 203–208.

Plan of the town of Singapore and its environs [cartographic material] (1854). Surveyed in 1842 by Government Surveyor, Singapore.

Proudfoot, I. (1994). The print threshold in Malaysia. Clayton: Centre of Southeast Asian Studies, Monash University. (Call no.: RSEA 070.509595 PRO)

Rich, E.E. (Ed.). (1941). The letters of John McLoughlin, from Fort Vancouver to the governor and committee, first series, 1825–1838. The Champlain Society of the Hudson’s Bay Record Society, 122.

Statham-Drew, P. (2005). James Stirling – Admiral and founding governor of Western Australia. Crawley: University of Western Australia Press.

Teo, E.L. (2009). Malay encounter during Benjamin Peach Keasberry’s time in Singapore, 1835 to 1875. Singapore: Trinity Theological College. (Call no.: RSING 266.02342095957 TEO)

The Illustrated London News. (1855, 13 January), pp. 43—45.

Domestic Occurences. (1867, January 21). The Straits Times, n.p. (reports the death of Otokichi).

The present tendency for mechanisation – Labour savings method. (1931, May 21). The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tokutomi, S. (1979). Kaikoku Nihon (Vol. 4) – Nichi∙Ro∙Ei∙Ran Jouyaku Teiketsuhen [Opening of Japan, Vol. 4 – Treaties of Japan with Russia, Britain, and the Netherlands]. Tokyo: Kohdansha Gakujutsu Bunko.

Williams, F.W. (1972). The life and letters of Samuel Wells Williams, LL.D., missionary, diplomatist, Sinologue. Winnington: SR Scholarly Resources.

Williams, S.W. (1837). Narrative of voyage of the ship Morrison, captain D. Ingersoll, to Lewchew and Japan, in the months of July and August, 1837. Chinese Repository, 6(5), 209–229, and 6(8), 353–382.

Voyages of the Himmaleh and Morrison in 1837. (1876). The Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal, 7(6), 396.

NOTES

-

Christianity in any form was strictly banned from Japan for 260 years from 1613. A decree prohibiting the Christian faith that was written on the Notice Boards set up on the streets was finally lifted on 24 February 1873. ↩

-

The Hojunmaru was one of the typical cargo ships in those days called sengoku-bune because they were built to carry around sen (one thousand) koku of rice (one koku being a little over the five bushels). They had a huge rudder at the back and only one mast-sail, for larger ships were strictly forbidden by the Tokugawa Government. They were only fit to carry goods along the coast or in the calm inland sea. ↩

-

National Geographic, Vol. 180, No. 4. (October 1991) has an extensive article on the Makah, and we can imagine how the Japanese men must have been treated for about four or five months. ↩

-

HBC was founded in London with a Royal Charter from King Charles II on 2 May 1670. It is still one of the largest companies in Canada. See the letter written by McLoughlin (dated 28 May 1834) telling about how he rescued the three shipwrecked Japanese. ↩

-

“Early Letter from the Northwest Mission”. Washington Historical Quarterly, 24, 1933, p. 54. Shepard’s letter first appeared in Zion’s Herald, Boston, 1835, p. 170. ↩

-

The Japanese language can be written in kanji (idiographic Chinese characters) and two kinds of syllabary: hiragana (the cursive phonetic syllabary) and katakana (the square phonetic syllabary, mostly used for writing foreign loanwords today, but in the earlier days, katakana was taught and read by the general public, while Chinese characters were taught chiefly to the children of samurai (warrior) families. ↩

-

HBC Archives, Section 3, Class 1, Piece 284, gives the ships logs of the Eagle, 1833–1835, by Captain W. Darby. ↩

-

A letter (dated 11 June 1835) from HBC London Office to Mr Wade say, “[the company] will send the three Japanese on board tomorrow or next day to be taken to Canton by the ‘General Palmer’” HBC Archives, A, 5/11, p. 47. ↩

-

Medhurst borrowed Japanese books from the Dutch East India Company and studied Japanese on his own, and published by lithograph An English and Japanese and Japanese and English Vocabulary (Compiled from Native Works). Batavia, 1830, pp. viii, 344. ↩

-

Akiyama (2006, p. 291) quotes the letter from Gützlaff’s Biography written in Dutch by G. R. Erdbrink, Gützlaff, de Apostel der Chinezen, in zijin Leven en zijne Werkzaamheid Geschetzt, 1850, p. 53) ↩

-

Several books have been written on this trip and readers can refer to these major references: Williams, 1837; King and Lay, 1839; Parker, 1838; and Aihara, 1954 (in Japanese). ↩

-

The Treaty of Nanjing, concluded at the end of the Opium war (or the Anglo-Chinese War) in August 1842 between the British and the Chinese (Qing dynasty), forced China to open five ports (Canton, Fuzhou, Xiamen, Linbou and Shanghai) for foreign trade and also surrender Hong Kong to the British) ↩

-

For instance, according to the general letter from the mission (dated 14 July 1839) “Mr Williams has usually devoted two hours in the morning to the study of Japanese, after which four hours to Chinese” (Missionary Herald, Vol 36, for the year 1840: 81). Williams wrote to his father (21 January 1838) that he was learning Japanese (Williams, F.W. (1972). The life and letters of Samuel Wells Williams, LL.D., missionary, diplomatist, Sinologue (pp. 107–108), and that he has a Japanese working at the printing office (26 January 1839; ibid, p. 110). ↩

-

Mathew Calbraith Perry (1794–1858), a veteran US naval officer, was sent to Japan to open diplomatic relations between the US and Japan. He left Norfolk on 24 November 1852 and arrived at Edo Bay on 8 July 1853 via Hong Kong with four “Black Ships”. He delivered President Fillmore’s letter to the Emperor of Japan at Kurihama and left for China. He revisited Japan with seven warships on 13 February 1854 and concluded the Treaty of Peace and Amity between the United States and the Emperor of Japan at Kanagawa (now called Yokohama) on 31 March 1854. For the detailed account, see the official report of the trip, Narrative of the expedition of an American squadron to the China seas and Japan, performed in the years 1852, 1853 and 1854, under the command of Commodore M.C. Perry, United States navy, by Order of the Government of the United States (1856). ↩

-

James Stirling (1791–1865), a veteran British naval officer, arrived at Nagasaki on 7 September 1854 to look for Russian warships as Britain was involved in the Crimean War (1853–56). With Ottoson as interpreter, Stirling concluded the first formal Anglo-Japanese agreement on 14 October 1854, which included an article that the ports of Nagasakai and Hakodate shall be open to the British ships. Refer to W. G. Beasley, (1995) and Illustrated London News (13 January 1885, pp. 43–45) for more detailed accounts. ↩

-

British Citizenship No. 205 was granted to Japanese John M. Ottoson as he met the conditions stated under No. 30 of 1852. ↩

-

The old record of Ryosanji Temple lists 14 posthumous names along with their fathers’ names and the same date of their death as 12 October (Tempo 3), the second day after they left Toba. On top of the page it is written in red ink, “Fourteen men listed from this column left Toba Port in the province of Shishu, but we do not know where they sank to death”. The owner of the Hojunmaru also erected a tomb in the temple graveyard in 1832 around which all the 14 names were carved. ↩

-

The Chinese Repository was terminated in December 1851, and in those 20 years there were about 20 articles written on Japan and Lewchew (Okinawa). The Editorial Notice given in the last issue (31 December 1851) says that the role of the magazine has been accomplished as the number of printing presses increased from 5 to 13, and the newspapers from 2 to 5. ↩

-

‘Japanese Type’, Missionary Herald, Vol. 44, No. 1 (January 1848). Home Proceedings, pp. 29–30. ↩

-

Missionary Herald for the year 1837, pp. 456–461. Report from Canton, dated 7 March 1837. The detailed description on the trip of the Himmaleh, see the Preface, Vol. 1, by King and Lay, 1839. ↩

-

Under the “Report of the Mission for the Year 1837” on the print by blocks for Chinese printing it reads: “Blocks have been prepared for the Life of Christ, of Moses, Joseph, Daniel, John, and Paul, and two or three other tracts by Mr Gutzlaff; for a revised edition of Milne’s Village Sermons, Medhurst’s Harmony of Gospels, the Gospels and Epistles of John in Japanese” (p. 419); Harvard-Yenching Misisonary Writings in Chinese Microfims, compiled by M. Poon (January 2006), also lists the title, translator’s name, the place and the year of publication. Retrieved from Chinsci bokee website. ↩

-

Nine copies exist outside Japan: ABCFM in Boston (three copies, one of them used to belong to Ira Tracy, one to S.W. Williams). Harvard University Library, American Bible Society (two copies), British Bible Society, British Library and Paris National Library. Seven copies exist in Japan: Tokyo Theological Seminary, Doshisha University (Kyoto), Japan Bible Society (two copies), Meiji Gakuin University, Tenri Library (Nara) and one owned by an individual. The original copies of John’s Epistles in Japanese exist only at two places: British Library and Paris National Library. ↩