A Life Less Ordinary: Dr Wu Lien Teh the Plague Fighter

Reference Librarian Wee Tong Bao sheds light on the life and achievements of plague fighter Dr We Lien-Teh, as well as the materials – such as books, magazines and photographs – donated by his family to the National Library Board.

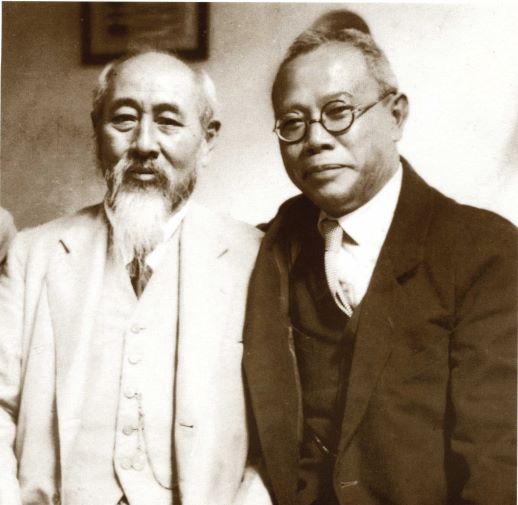

In November 2010, the family of the late Dr Wu Lien-Teh donated a collection of some 65 items to the National Library of Singapore. They include publications on his life and works as well as some 140 photographs dating back to the early 1910s. The donation also marked the 50th anniversary of Wu’s death; he passed away in 1960 at the age of 81.

Dr Wu Lien-Teh

Wu was born in Penang in 1879. His birth name was Ng Lean-Tuck (伍连德,meaning “five united virtues”; romanised according to its Cantonese pronunciation). His father, Ng Khee Hok, was an emigrant from Taishan, Guangzhou, China, and he ran a successful goldsmith business in Penang where he married Lam Choy-Fan in 1857. They had eight children and Wu was the fourth child.

Wu received his early education at the Penang Free School. In 1896 the young Wu won the only Queen’s Scholarship of that year after a competitive examination for boys in the Straits Settlements.

The scholarship enabled Wu to be admitted to Emmanuel College, Cambridge University, for medical studies. He was the first Chinese medical student at Cambridge and the second to be admitted to Cambridge, the first being Song Ong Siang.

Wu obtained First Class Honours at Cambridge and received the gold medal for clinical medicine in 1902. He won a travelling scholarship which allowed him to pursue research work in Liverpool, Paris, parts of Germany and the Malay States. During this period, he produced scholarly papers on tetanus, beri-beri, aortic worms and malaria.

At age 24, Wu earned his medical degree and returned to the Straits Settlements in 1903. He joined the newly established Institute for Medical Research in Kuala Lumpur for one year where he conducted research on beri-beri, then a killer disease. Thereafter, he spent the next three years (1904–07) in private practice in Penang. It was also during this time that Wu became occupied with the social issues of the day and got passionately involved in social reform work through the influence of another prominent doctor, Dr Lim Boon Keng.

Wu was particularly zealous in the campaign against opium addiction. At the age of 25 in 1904, he became the President and Physician-in-Chief of the Penang Anti-Opium Association which he had founded. Through this association, he raised funds to provide free lodging, food, medication and treatment for all addicts who needed help. Two years later in March 1906, Wu organised the first Anti-Opium Conference of the Straits Settlements and the Federated Malay States. The conference was held in Ipoh and attended by more than 2,000 representatives from various trades and professions.

It was also through Lim that Wu met his first wife, Ruth Huang Shu Chiung, the sister of Dr Lim’s wife. Ruth was the second daughter of Wong Nai-Siong, a noted Chinese scholar who played a key role in the establishment of a Foochow settlement in Sarawak. They married in 1905, making Wu and Lim brothers-in-law. Wu and Ruth had three sons: Chang-Keng, Chang-Fu and Chang-Ming. Ruth, unfortunately, fell victim to tuberculosis and passed away in 1937. Wu later married Lee Shu-Chen (Marie), with whom he raised three daughters and two sons: Yu-Lin, Yu-Chen, Chang-Sheng, and Chang-Yun and Yu-Chu.

In 1908, Wu became the Vice-Director of the Imperial Army Medical College in Tianjin, China, at the invitation of Yuan Shi-Kai (who was then the Grand Councillor of China) to train doctors for the Chinese Army. He used the romanised version of his name in Mandarin “Wu Lien-Teh” from then onwards.

On 19 December 1910, the Foreign Office (China) sent Wu to investigate a mysterious disease that was killing hundreds. A bacteriologist by training, he “naturally jumped at the opportunity, and after two days’ preparation, proceeded to Manchuria with a senior student of [his] from the Army Medical College”.1

In his book A Treatise on Pneumonic Plague, Wu recounted how the journey took him three days and nights on the South Manchurian and Chinese Eastern Railways. When he arrived late on Christmas Eve, the temperature was varying between –25 deg C and –35 deg C, “much more severe than anything [he] had known”.2

Early cases of the plague were reported in the first week of November 1910. Initially, only a few victims were identified. However, from the beginning of December, things took a sudden turn for the worse with up to 15 deaths recorded daily.

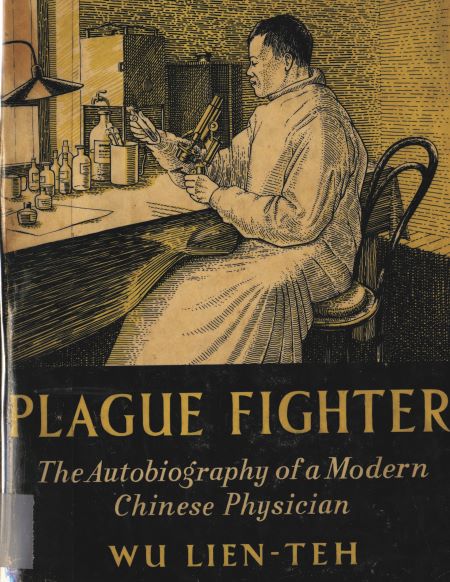

Wu, as the Commander-in-Chief of the anti-plague organisation, had effective control over doctors, police, military and civil officials. To curb the plague from spreading, he sought an Imperial edict to cremate more than 3,000 corpses that had been lying unburied on the frozen ground. In the book Plague Fighter: The Autobiography of a Modern Chinese Physician, it was said that “this proved to be the turning point of the epidemic”.3

Wu vividly remembered that the cremation took place on 31 January 1911. In his own words, “their [plague corpses] disappearance was in the eyes of the public a greater and more glorious achievement than all our other anti-plague efforts combined. From that day, the death rate steadily declined and the last case was reported on March, 1st”.4

The eradication of the 1910–11 plague had a great impact on the medical future of China. In April 1911, soon after the end of the epidemic, China held its first-ever international scientific conference in Mukden, Shenyang – the International Plague Conference – which was attended by important scientists from 11 nations. In 1912, the Manchurian Plague Prevention Service was established with Wu as the director. In 1915, the Chinese Medical Association was founded, and four years later, in 1919, the Central Epidemic Bureau was established in Peking.

Besides quashing the 1910–11 plague, Wu also contributed to the control of the cholera epidemic in Harbin which broke out in 1919 and a second pneumonic plague that occurred in North Manchuria and East Siberia in 1920–21.

Wu’s illustrious medical career in China spanned almost three decades. During this period, he represented the Chinese government at various international conferences, both within and outside China. He also contributed much to the modernisation of China’s medical services, improvements in medical education and development of quarantine control. In 1937, when Japan invaded China, Wu returned to Malaya and remained there until he passed away on 21 January 1960.

The Wu Lien-Teh Collection

Although Wu spent 23 years in Malaya since his return from China, his contributions to the development of health sciences in China were not forgotten. He received publications and articles reporting on his deeds over the years and his family continued to get these materials after he passed away. In 2010, the family decided to donate some of these materials, including Wu’s own works, to the National Library, Singapore.5

In all, about 65 publications were donated by Wu’s family. They include books, souvenir magazines, periodicals and photographs. One of the earliest publications in this donation is Biographies of Prominent Chinese.6 This book, measuring 24 x 37 cm, contains 200 pages and was compiled as a result of a “growing demand for a more intimate understanding of those Chinese who contributed to the development and progress of the Chinese Republic”.7 This book was mentioned by the Straits Times on 15 October 2011, with the reporter writing that to-date, only two known copies exist.8 The page that introduces Wu was reproduced in a biography by his daughter, Dr Wu Yu-Lin’s Memories of Dr Wu Lien-Teh: Plague Fighter.9

There are more recent works among the donated items that honour Wu: a 1996 issue of London’s British Medical Journal that ran an announcement about the new book, Dr Wu Lien-Teh: The Plague Fighter,10 and the 2006 souvenir magazine of Harbin Medical University that acknowledged his contributions.11 In 2007, preparations began for a television series in Harbin to mark the 130th anniversary of his birth.12

In this donation, there are also a small number of works by Wu himself. His writings often entailed years of thorough research and are still hailed as significant works in their respective fields today. Two works worth highlighting are League of Nations, Health Organisation: A Treatise on Pneumonic Plague13 and History of Chinese Medicine 《中国医史》co-authored with Wong K.C.14 The first title is a firsthand account of Wu’s battle against the 1910–11 Manchuria plague. In the preface, he called the book “a labour of love”.15 The book contains in-depth research of the history, epidemiology, pathology, clinical features, infectivity, immunity and other aspects of the pneumonic plague. It took him 17 years to prepare this publication and it was duly endorsed by the United Nations.

The second title was a mammoth effort in recording the history of Chinese medicine from its early beginnings – 2690 to 1122 BCE – till the introduction of western medicine. Wu started conceptualising this book 15 years before it was published in 1932. This epic account took two dedicated writers – Wu and Wong K.C. – to complete. The title filled a gap at the time, and just four years after it was published, a second edition was released in 1936.

Among the donated items, one can also find Wu’s autobiographym Plague Fighter: The Autobiography of a Modern Chinese Physician,16 and the Chinese edition containing selective sections published in 1960.17

Besides Wu, his first wife Ruth was also well educated and had published three books in the 1920s and 1930s. During her years accompanying her husband in China, Ruth decided to write on four renowned beauties in China’s history: Yang Kuei Fei (Yang Gui Fei), Hsi Shih (Xi Shi), Chao Chun (Zhao Jun) and Tiao Chan (Diao Chan). However, Ruth only managed to publish books on the first three beauties before she passed away in 1937. With this donation, the National Library of Singapore received a copy of Chao Chun: Beauty in Exile,18 which completes the set of early publications by Ruth. Before this, the Library only had two of the first imprints: the 1924 edition of Yang Kuei-Fei: The Most Famous Beauty of China19 and Hsi Shih: Beauty of Beauties: A Romance of Ancient China About 495–472 BC.20

Library Holdings

The donated items in this collection are assigned the location code “RCLOS” (closed-access materials). Readers who are interested in these publications can access them at Level 11 of the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library, Singapore. These items can be consulted upon request at the Information Counter.

Reference Librarian

NL Heritage, National Library Board

NOTES

-

Wu, L.T. (1926). A treatise on pneumonic plague. Geneva: League of Nations Health Organisation, p. v. (Call no.: RCLOS 616.9232 WU) ↩

-

Wu, L.T. (1995). Memories of Dr Wu Lien-Teh: Plague fighter. Singapore: World Scientific Pub., p. 28. (Call no.: RSING 610.92 WU) ↩

-

Leong, W.K. (2010). Life and works of a legendary plague fighter. The Straits Times, p. 31. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Burt, A.R., Powell, J.B., & Crow, C. (Eds.). (1925). 中华今代名人传 = Biographies of prominent Chinese. Shanghai: Biographical Publishing Company Inc. (Call no.: RCLOS 951.080922 BIO) ↩

-

Burt, Powell & Crow, 1925, publisher’s note, n.p. ↩

-

Teng, A. (2011, October 15). Long-lost tomb helped her to uncover heritage. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

British Medical Journal (International edition). No. 7035, Vol. 315, April 1996. London: British Medical Association, p. 916. ↩

-

马宏坤等编. (2006). 《哈尔滨医科学校80周年纪念特刊, 2006年》, trans. Harbin Medical University 80th Anniversary souvenir magazine, 2006. ↩

-

德道传媒. (2009?). 哈尔滨人民纪念伍连德 : 暨电视剧《伍连德》项目文献集粹”, trans. “Wu Lian De” TV series – dedicated to Dr Wu Lien-Teh on the 130th anniversary of his birthday. ↩

-

Wong, K.C., & Wu, L.T. (1936). History of Chinese Medicine 《中国医史》. Shanghai: National Quarantine Service. 2nd edition. (Call no.: RCLOS 610.951 WAN) ↩

-

Wu, L.T. (1959). Plague fighter: The autobiography of a modern Chinese physician. Cambridge: W. Heffer & Sons. (Call no.: RCLOS 926.1 WU) ↩

-

伍连德. (1960). 《伍连德自传》. Singapore: Singapore South Seas Society. ↩

-

Huang, S.C.R. (1934). Chao Chun: Beauty in exile. Shanghai: Kelly & Walsh Limited. (Call no.: RCLOS 828.995103 SHU) ↩

-

Huang, S.C.R. (1924). Yang Kuei-Fei: The most famous beauty of China. Shanghai: Kelly & Walsh Limited. (Call no.: RCLOS 920.72 SHU) ↩

-

Huang, S.C.R. (1931). Hsi Shih: Beauty of beauties: A romance of ancient China about 495–472 B.C. Shanghai: Kelly & Walsh Limited. (Call no.: RCLOS 920.72 SHU) ↩