Spicy Nation: From India to Singapore

From fish head curry to Indian rojak, Indian food in Singapore has evolved over time, drawing influences from various local cultures, and finding its place in the hearts of Singaporeans.

“The discovery of a new dish does more for the happiness of man than the discovery of a star.”

Indian cuisine is one of the most diverse in the world. India’s rich culinary heritage is closely linked with its ancient culture, traditions and mosaic of religious beliefs. Each region in India, despite using almost the same basic spices and herbs, employs a range of cooking techniques to produce unique and tantalising dishes found nowhere else in the world.

A Spice for Every Need

Spices are the heart and soul of Indian cuisine. The use of spices has been an ancient tradition “recorded in Sanskrit texts 3,000 years ago”.1 The secret of Indian cuisine lies in the artful combination of spices, finding the right balance of each spice and tempering them skilfully in order to give each dish its distinct full-bodied flavour and aroma.

Spices are also believed to have medicinal properties. India’s ancient Ayurvedic medicine offers a “holistic form of healing”2 that lists the five basic tastes: sweet, sour, salty, pungent and bitter. Spices such as asafoetida, anise, cinnamon, cumin, turmeric, clove, fennel, cardamom, nutmeg, fenugreek seeds, mustard seeds, saffron, coriander, curry leaves, bay leaves along with chilli, ginger, onion and garlic (many of which are grown in India) are commonly used to relieve indigestion, infections, the common cold, arthritic pains, and even to keep cholesterol levels in check and protect against heart disease. Spices are so important to India that a dedicated Spices Board was established in 1986 with 32 members with headquarters in Cochin, Kerala.3

Apart from using spices individually, masala, basically a mix of spices, is used to add flavour even to the simplest of dishes.4 Masala comes in various combinations, from dry mixtures to wet pastes, from the more common North Indian garam masala – typically a mix of peppercorn, cumin, clove, cinnamon and cardamom pods – to a fiery South Indian coconut-based masala. These masala concoctions can range in taste from mild to searingly hot.

North Indian Delights

Although influenced by different religions and traditions, as well as varying regional climates, India’s culinary delights can generally be categorised into northern and southern cuisines.

The Moghuls who ruled northern India for 300 years were Muslim, and this region has many Indian restaurants that do not serve pork. The Moghuls introduced the Persian style of cooking to Indian cuisine, which is why North Indian food is milder and less restrained in its use of spices. Mughali dishes, such as creamy korma curries and fragrant rice dishes like briyani and pulao use exotic spices as well as dried fruits and nuts.5 It is also in the north, at the Himalayan foothills of Jammu and Kashmir and Dera Dun, where basmati rice (a long-grain rice known as the “the king of rice”) is grown.6 This aromatic rice is used in the cooking of briyani and complements most Indian food.

Another popular dish in North India is tandoori chicken, traditionally cooked in a tandoor (clay oven). It is simply prepared with yogurt and spices yet this tantalising dish is a favourite with many diners. A popular Kashmiri dish, roghan josh is lamb marinated in yogurt and spices. Mishani is a seven-course lamb dish that is widely served at Kashmiri weddings and highly sought after in wedding menus.

Punjab, also known as the breadbox of India, is famous for its assortment of leavened and unleavened bread, such as naan, chapati bread and tandoori roti. Interestingly, it was the Moghuls from Persia who introduced naan (“bread” in Persian) to northern India.

Fiery South Indian food

The time-honoured food traditions of South India continue to this day, and it is not unusual to see South Indians sitting cross-legged on a floor mat eating off a stainless steel plate (thali) or a fresh banana leaf. South Indian dishes are typically spicier than their North Indian counterparts, and often include coconut (used to make chutneys and curries) and rice, which is a staple food in the south. South Indian dishes do not use as much ghee (clarified butter) and yoghurt as North Indian ones. Many spices, such as fenugreek, dried red chillies, mustard seeds and peppercorn, used in South Indian cooking lend the cuisine its fiery reputation. Common South Indian dishes include dosa (crispy savoury pancakes; or thosai), idli (steamed rice cakes), sambhar (lentil curry) and vadai (fritters).

Indian Sweets

Whether in the north or south, sweets, most of which are highly calorific and contain lashings of sugar and ghee, are traditionally served after meals. Payasam (in Tamil) or kheer (in Hindi), made of rice or wheat vermicelli, is commonly eaten during festive occasions and weddings. The payasam served at Ambalappuzha Temple (see text box) in Kerala is especially famous among Hindu devotees.7

Other traditional Indian sweets include gulab jamun, mysore pak, halwa and laddoo. Gulab jamun are little balls of milk powder and plain flour deep fried and drenched in sugary syrup, usually served at North Indian weddings. Mysore pak – made of ghee, gram flour and sugar – hails from Mysore, in the southern state of Karnataka. It is often referred to as a royal sweet as it was concocted in the kitchen of Mysore Palace for the king. There are several variations of halwa, with either semolina, wheat flour, mung bean or carrot as its base, while laddoo are bright orange ball-shaped confections offered as a prasad (gift) to guests at weddings and religious occasions.

The Origins of Vegetarianism

The roots of vegetarianism in India can be traced to religions such as Buddhism, Jainism and Hinduism. Many consider “Indian cuisine… to be the cradle of vegetarian culinary art”.8 Gujaratis, who are mostly vegetarian, have perfected the art of vegetarian cooking. Using the simplest ingredients, they transform the most basic dishes into mouthwatering delicacies. Typically, a Gujarati meal begins with cumin-spiked buttermilk, followed by hot fluffy roti (unleavened bread) accompanied by a variety of lentils, vegetables, curds and pickles.

South Indians also offer an astonishing variety of vegetarian dishes. Both Karnataka and Tamil Nadu have a “strong vegetarian bent to their cuisine”.9 In Kerala, during an ancient harvest festival known as Onam, as many as 24 vegetarian dishes are served in just one sitting. Indian cooks take great pride in creating exciting vegetarian dishes out of exotic greens like snake gourd, ridge gourd and the pod-like drumstick or murungaltai in Tamil, as well as more prosaic leafy vegetables, lentils, dried beans of all kinds, and unripened jackfruit and plantains.

Indian Vegetarian Restaurants

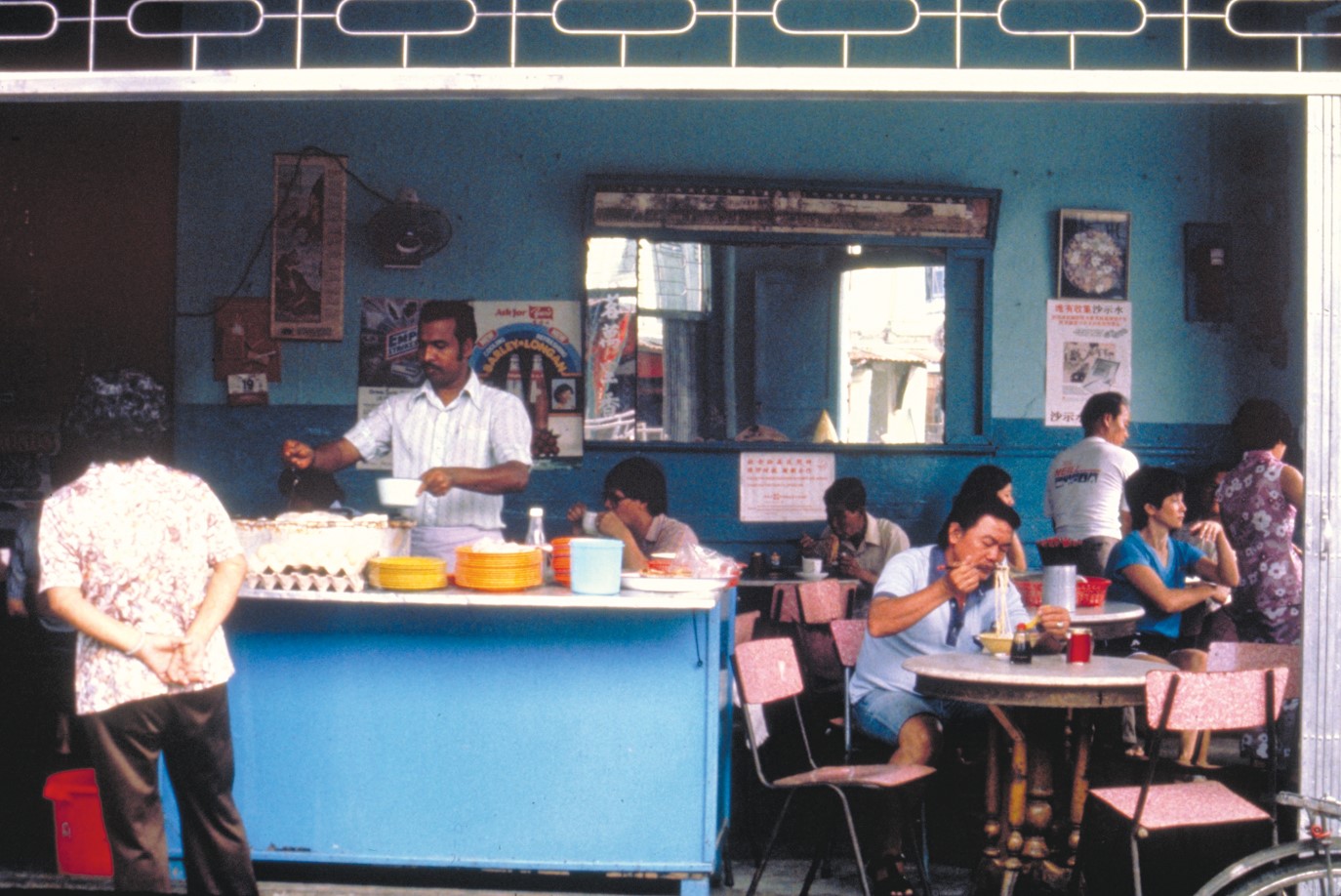

Multicultural Singapore is a food paradise. Among the many local cuisines available here, Indian food is one of the favourites. Early Tamil immigrants opened their first Indian vegetarian eatery, Ananda Bhavan Vegetarian Restaurant, in 1924 along Selegie Road to satiate the appetites of homesick Indians. Known as the “most authentic old world restaurant”,10 the original Selegie Road outlet has since closed but there are five branches, the largest of which is located along Serangoon Road. Its signature dishes cover a wide range of traditional dishes such as thosai, idli, chapati (bread made from whole wheat flour) and puri (deep-fried bread).

Komala Vilas, another vegetarian restaurant, opened in 1934, and has been proclaimed by some as the most popular vegetarian restaurant in Singapore. The restaurant owner, Mr Gunasekaran, attributed the continued popularity of Komala Vilas to the successful retention of its traditional flavours all these years without any compromise. His late father, Mr Rajoo, whose hometown is in Thanjavur, which is renowned for its good food, in South India’s Tamil Nadu, was the founder of Komala Vilas. “Komala” was the name of his boss’s wife and “vilas” means home. So Komala Vilas means a home for good Indian vegetarian food.

The speciality at Komala Vilas is the masala thosai, which is so popular that even non-Indians love it. This is a crisp, savoury and thin pancake eaten with potatoes spiced with masala. Other accompaniments include sambhar (lentil curry) and coconut chutney. The restaurant hardly advertises and it has been through word of mouth that Komala Vilas has expanded to three locations and is now a household name in Singapore.

When Mr Gunasekaran noticed more and more people ordering masala thosai, he added more varieties. The menu has since expanded from simple thosai to other South Indian dishes like idli, variations of thosai (crisp thin Indian pancake), rava thosai (thosai made with semolina flour), pepper thosai, utthappam (thick pancake), vadai (a savoury snack made from dal, lentil or gram flour and deep-fried), as well as North Indian meals with an assortment of chutneys. Its subsidiary, Komalas, run by Mr Gunasekaran’s brother, employs a fast-food concept to vegetarian food.

Singaporean Indian Fare

Some of the most renowned Indian restaurants in Singapore are Samy’s Curry, which opened in the 1950s, Muthu’s Curry in 1969 and Banana Leaf Apolo in 1974. These three restaurants are particularly known for their mouthwatering and eye-poppingly hot fish head curry. Few people are aware that fish head curry is actually a Singaporean concoction. Eating the fish head is not something common among ethnic Indians, as only those who could not afford to buy the whole fish would eat the head. On the other hand, the Chinese had long ago discovered the delectable sweetness of the flesh from the head and cheeks of a fish. The Teochews, for instance, eat steamed fish head with ginger and pickled vegetables. Enterprising Indian restaurateurs must have noticed this peculiar habit and decided to experiment cooking fish head with curry spices instead, leading to the birth of this fusion dish.11 No one could have imagined its popularity.

The genesis of fish head curry can be traced to an Indian migrant, Mr M.J. Gomez, who originally came from Kerala. He “began humbly with an eating shop in Mt Sophia which was, back in 1952, a relatively quiet little suburban backwater behind the Cathay cinema. The most famous dish, prepared by Gomez, was fish head curry, a culinary delight reputedly unknown in Singapore before his arrival”.12 Mr Gomez used the huge heads of ikan merah and grouper in a piping hot and spicy curry dish complemented by chunks of eggplant and lady’s fingers, and flavoured with onions, garlic, ginger, turmeric, chilli and curry leaves. Fish head aficionados know that the tastiest part of the fish head are the fleshy pockets at the side of the head, where the meat is the sweetest and most textured.13

The Gomez eatery eventually closed, but with the opening of Muthu’s Curry in 1969, the fish head curry craze was revived. From a small coffee shop on Klang Road, the restaurant now has three outlets at Race Course Road, Suntec City and Dempsey Road. Today, fish head curry is one of Singapore’s most iconic foods. This single dish from Muthu’s Curry has won numerous accolades such as “Best Local Dish” by the Singapore Tourism Board, “Best Fish Head Curry” by Makansutra and “Best Local Food – Fish Head Curry” by Singapore Tatler from 2010 to 2013.14

Nasi briyani is another beloved Indian dish in Singapore. Islamic Restaurant along North Bridge Road is one of the oldest culinary institutions in Singapore, started by the late Mr M. Abdul Rahman in 1921. Prior to the opening of his restaurant, he had been the “head chef for the Alsagoffs”, serving the renowned briyani to foreign guests of this prominent Arab family in Singapore. This dish eventually became the signature dish for Islamic Restaurant. Patronised by many of Singapore’s leaders such as former presidents Yusof Ishak and S.R. Nathan, Islamic Restaurant is still a favourite haunt of foreign politicians like former Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak.15

Another example of a hybrid Indian dish is mee goreng – yellow wheat noodles fried with chillies, potato cubes, bean sprouts, tomato ketchup and spices. It may have been adapted from the Chinese fried noodle dish, char kway teow, to suit the Indian palate. The Tamil-Muslim Chulia community originally from Madras (present-day Chennai) popularised the dish, and this is why it is associated with the Indian Muslim community in Singapore.16

Indian rojak is another fusion dish unique to Singapore (in Malaysia it is referred to as pasembor). Apparently, the Tamil Muslims who came from Thakkalai in Tamil Nadu were inspired by mee siam gravy and decided to adapt it by using mashed sweet potatoes as a thickener. This spicy and sweet gravy is served as a dipping sauce for deep-fried chunks of tofu, potatoes, tempeh, hard-boiled eggs and flour fritters.

Sup kambing, or mutton soup, is another Indian Muslim fusion dish that took its cue from Chinese cuisine. Soup is almost never served in Indian households, but in this hybrid dish, chunks of mutton is slow-cooked in a robust, peppery soup and served with cubes of crusty French loaf.

Indian food is one of the world’s oldest cuisines with a long and rich tradition. With the spread of the Indian diaspora to Singapore, Indian cuisine here has evolved, picking up Southeast Asian ingredients and nuances in flavour. Authentic Indian restaurants abound in Singapore, but of more interest to culinary historians is the impact of Indian food on the local food scene and the interesting amalgamation of Indian and regional flavours that result in uniquely Singaporean dishes. In this sense, food can be seen as a physical manifestation of Singapore’s multicultural society, where the influence of one cuisine upon another results in something quite extraordinary.17

CURRY, CURRY LEAVES AND CURRY POWDER

An assortment of spices that make up curry powder. Hildgrim, via Flickr.

An assortment of spices that make up curry powder. Hildgrim, via Flickr.

Native to India and Sri Lanka, the curry leaf is an important herb in South Indian cooking. This small, fragrant and dark green leaf has a distinctive peppery flavour that adds robustness to any dish. Curry leaves are chopped or used whole and added to hot oil for tempering, and used as garnishes in salads, curries, marinades and soups to improve the taste. As observed by Wendy Hutton in Singapore Food (2007), the Indians say there is “no substitute for these small, dark green leaves from the karuvapillai tree”. The use of curry leaves is even mentioned in early Tamil literature dating back to the 1st to 4th century CE.

Intriguingly, what we commonly understand as “curry” originates from a Tamil word for spiced sauces. More specifically, it refers to “a mixture of spices including cumin, coriander, turmeric, fennel, fenugreek, cloves, cinnamon, cardamom and often garlic, with chilli [as] the dominant spice”. Curry powder is actually something that the British created for commercial reasons and in fact never existed in India until the 18th century. A curry could have plenty of gravy from the use of coconut milk, yoghurt or pulverised dhal, or legumes to thin out the spice mixture. Dry curries, on the other hand, tend to be more intense in flavour as most of the liquid used in their preparation has been allowed to evaporate.

A LEGENDARY DESSERT

According to Hindu legend, Lord Krishna transformed into an old sage one day and challenged the arrogant king of the region of Kerala to a chess game. The wager for the game was rice. Eventually, the king lost the game as well as his kingdom’s precious rice reserves. Lord Krishna revealed his true identity and told the king that instead of giving him his rice, he should instead serve payasam – a dessert porridge made of rice, ghee, milk and brown sugar, and garnished with raisins and cashew nuts – to pilgrims who visited the Ambalappuzha Temple in Kerala. In many Indian vegetarian restaurants today, a variation of payasam made of broken bits of wheat vermicelli instead of rice is served as a sweet ending to the meal.

THE UBIQUITOUS ROTI PRATA

Roti prata is today an integral part of Singapore’s cuisine. rpslee, via Flickr.

Roti prata is today an integral part of Singapore’s cuisine. rpslee, via Flickr.

Roti prata is the most popular and common Indian food in Singapore. Indian migrants brought this griddle-toasted flatbread to Singapore; by the 1920s, this dish was established throughout the Malayan peninsula.18 It is thought to have originated from Madras where it is known as parota. Some believe that it originated from Punjab where it is called prontha or parontay. In South India and Bengal, it is called parotta, porotta or barotta, while in Sri Lanka, it is known as kothu parotta. In Mauritius and the Maldives, it is called farata, and in Myanmar, palata. Across the causeway in Malaysia, it is known as roti canai. While some believe canai refers to “Chennai”, others say it is derived from the Malay word for the process of kneading and shaping the dough.19

Roti prata is a crisp and flaky flatbread that is often eaten with a Hyderabadi-style mutton rib curry cooked with lentils called dalcha. Over time, Singapore has evolved into a prata paradise with many innovative incarnations of prata available in Indian Muslim food stalls and restaurants. Prata shops like Thasevi Food on Jalan Kayu and The Roti Prata House at Upper Thomson among others offer numerous varieties, from egg prata and chicken floss prata to combination flavours like cheese and mushroom, cheese and pineapple, cheese and chicken, and even ice-cream. There is also a prata buffet available at the Clay Oven restaurant on Dempsey Road. The humble roti prata is ranked no. 45 on the World’s 50 Most Delicious Foods, a readers’ poll compiled by CNN Go in 2011.20

REFERENCES

Association of Dutch Businessmen in Singapore. (2008, July–August). ADB newsbrief: A publication of the Association of Dutch Businessmen in Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 330.95957 ADBN)

An interview with Mr Gunasegaran, 11 January 2013.

Ananda Bhavan Vegetarian. (2018). Retrieved from Anandabhavan.com website.

Brinder, N. et al. (2004). The food of India: 84 easy and delicious recipes from the spicy subcontinent. Singapore: Periplus Editions. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Chapman, P. (2007). India food & cooking: The ultimate book on Indian cuisine. London: New Holland. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Cheung, T. (2017, July 12). Your pick: World’s 50 best foods. Retrieved from travel.cnn.com website.

Daley, S., & Hirani, R. (2008). Cooking with my Indian mother-in-law. London: Pavilion. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Dalmia, V., & Sadana, R. (Eds.). (2012). The Cambridge companion to modern Indian culture. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. (Call no.: 954.05 CAM)

History of Indian Food. (n.d.) Retrieved from Haldiram website.

Hutton, W. (2007). Singapore food. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Cuisine. (Call no.: RSING 641.5955957 HUT)

Indian cookery: Piquant, spicy & aromatic. (2007). Cologne: Naumann & Gobel. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Joshi, A., & Roberts, A. (2006). Regional Indian cooking. North Clarendon, VT: Periplus. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Kenihan, K. (2004). Indian food. Brunswick, Vic.: R & R Publications. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Kew Royal Botanic Gardens. Plant cultures: Curry leaf. Retrieved from Kew.org website.

Malhi, M. (2011). Classic Indian recipes: 75 signature dishes. London: Hamlyn. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Narula, B. et al. (2004). Authentic recipes from India. Singapore: Periplus Editions. (Not available in NLB holdings)

National Library Board. (2016). Mee Goreng written by Tan, Bonny. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website

Panickar, G. (2013, July 19). Prata paradise. Tabla, p. 14. Retrieved from Tabla website.

Sanmugam, D., & Shanmugam, K. (2011). Indian heritage cooking. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Cuisine. (Call no.: RSING 641.595957 DEV)

Siddique, S., & Shotum, N. (1990). Singapore’s little India: Past, present, and future. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 305.89141105957 SID)

Sur, C. (2003). Continental cuisine for the Indian palate. New Delhi: Lustre Press/Roli; Lancaster: Gazelle. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Tan, B. (2013). Ask the foodie kitchen knowhow explained. Singapore: Straits Times Press. (Call no.: RSING 641.5 TAN)

Tay, L. (2012). Only the best!: The ieat, ishoot, ipost guide to Singapore’s shiokiest hawker food. Singapore: Epigram Books. (Call no.: RSING 641.595957 TAY)

Tay, L. (2012, March 5). Islamic Restaurant: The granddaddy of Briyanis! Retrieved from ieatishootipost website.

The Straits Times’ annual 1974 (p. 86). Retrieved from Roots website.

Wickramasingher, P., & Selva Rajah, C. (2002). The food of India. London: Murdoch Books. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Wong, D., & Wibisono, D. (2001). The food of Singapore: Authentic recipes from the Manhattan of the East. Singapore: Periplus Editions. (Call no.: RSING 641.595957 WON)

NOTES

-

Brinder, N. et al. (2004). The food of India: 84 easy and delicious recipes from the spicy subcontinent (p. 11). Singapore: Periplus Editions. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Joshi, A., & Roberts, A. (2006). Regional Indian cooking (p. 8). North Clarendon, VT: Periplus. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Wickramasingher, P., & Selva Rajah, C. (2002). The food of India. London: Murdoch Books. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Malhi, M. (2011). Classic Indian recipes: 75 signature dishes (p. 9). London: Hamlyn. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Wickramasingher & Selva Rajah, 2002, p. 13. ↩

-

Joshi & Roberts, 2006, p. 33. ↩

-

History of Indian food. Retrieved from Haldiram.com website. ↩

-

Brinder, 2004, p. 13. ↩

-

Wickramasingher & Selva Rajah, 2002, p. 17. ↩

-

Ananda Bhavan Vegetarian. (2018). Retrieved from Anandabhavan.com website. ↩

-

The Straits Times’ annual 1974 (p. 86). Retrieved from Root.sg website. ↩

-

The Straits Times’ annual 1974, pp. 88–89. ↩

-

National Heritage Board. (2021, October 18). Fish head curry. Retrieved from Roots website. ↩

-

National Heritage Board, 18 Oct 2021. ↩

-

Tay, L. (2012, March 5). Islamic Restaurant: The granddaddy of Briyanis! Retrieved from ieatishootipost website. ↩

-

Sanmugam, D., & Shanmugam, K. (2011). Indian heritage cooking (p. 36). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Cuisine. (Call no.: RSING 641.595957 DEV) ↩

-

Sur, C. (2003). Continental cuisine for the Indian palate. New Delhi: Lustre Press/Roli; Lancaster: Gazelle. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Panickar, G. (2013, July 19). Prata paradise. Tabla, p. 14. Retrieved from Tabla website. ↩

-

Panickar, 19 Jul 2013, p. 14. ↩

-

Cheung, T. (2017, July 12). Your pick: World’s 50 best foods. Retrieved from travel.cnn.com website. ↩