About the Painters: Seeking the Unnamed Artists Behind Diard and Duvaucel's Natural History Drawings

Natural history drawings might seem clinical and cold, but an unlikely medium pulls back the curtains to find the humanity behind them.

By Chrystal Ho

It is said that they didn’t have names,

that those names were lost to time.

As if there wasn’t the one who never coloured

the eyes in when he was done, fearing

that the birds would come back to life,

the way a dragon once swam off a scroll

and into some curliqued clouds far away.

Then there was the one who painted

his lizards about to crawl off the edge

of each page, in the manner a lizard tends

to vanish in the space between a wall

and the next, under the watchful eye

of a child who crumbles her crayon

in her fist, or the painter’s, his eyes

barely flitting away from the lizard to

his page, before staring at the wall again.

It was almost as if I was there, myself,

shadowing the one who heeded

the sunbird’s chirp, as he searched

for food and shelter amidst the eaves

of our water jasmine shrub: once,

there was a painter who also noticed,

in a shrub not yet big enough to provide shelter,

the soft yellow down of a bird’s breast, cut

out of sight by the branch on which he perched.

It didn’t matter whether the bird was seen

drinking directly from small white flowers,

if the flowers were in bloom, or if they ever

existed at all, so long as his slender beak

will always have the curve of a polished nail,

always be pointing curiously at something,

somewhere else.

In 1818, two French naturalists, Pierre-Médard Diard and Alfred Duvaucel, travelled to Southeast Asia to study the region’s wildlife.1 As part of this process, they collected specimens of species new to them and hired artists locally to produce drawings of these specimens.2 These stunning illustrations are collected today in Diard & Duvaucel: French Natural History Drawings of Singapore and Southeast Asia, 1818–1820.3 While these 117 illustrations provide valuable documentation of some of the region’s fauna at that time, all of them are unsigned.4 Since the names of these artists are not known to be documented anywhere, their identities remain a perennial mystery.

While the subject matter of these drawings was naturally of interest to my research as part of my eco-poetry project, Where the Flowers Never Stop Blooming, for the National Library Creative Residency, I was more intrigued by the question of who these artists were. Given that these artists had accompanied Diard and Duvaucel on their expeditions, working on the illustrations “when [the animals] were either still alive or soon after death”,5 how did their personal encounters with wildlife influence their artistic approaches? In this process essay, I delve into the research behind my poem, “About the Painters”, which responds to the question of the painters’ identities by creatively reimagining the human-nature encounters behind the illustrations.

Aesthetic Emotion

A key text that undergirds my approach is art critic John Berger’s essay on aesthetics, “The White Bird”. In this essay, Berger surmises that art is “an attempt to transform the instantaneous into the permanent”.6 Here, the “instantaneous” refers to spontaneous and unexpected encounters with beauty in nature.7 These unpredictable encounters are moments of double affirmation, where “what has been seen is recognised and affirmed, and, at the same time, the seer is affirmed by what he sees”.8 “Aesthetic emotion”, which derives from this moment of double affirmation, is what art attempts to make permanent.9

Drawing on Berger’s theory, if we consider natural history drawings to be works of art, then they can also be treated as endeavours to make permanent aesthetic emotion. Even if the drawings were originally commissioned for the purposes of scientific study,10 the artists, being personally present on these expeditions,11 would have experienced the spontaneous aesthetic emotions arising from encounters with nature.

Marks of the Artists

Taking a closer look at the natural history drawings in the William Farquhar Collection at the National Museum of Singapore – likewise drawn by Chinese artists whose identities remain unknown – can provide us with insight into how impersonal natural history drawings can reveal private details. As Kwa Chong Guan discusses in “Drawing Nature in the East Indies: Framing Farquhar’s Natural History Drawings”, “personal stylistic differences”, such as the presence or absence of a border around each drawing, or whether rocks in the landscape were more stylised or naturalistic, might “suggest that [the drawings] were the work of at least two artists”.12

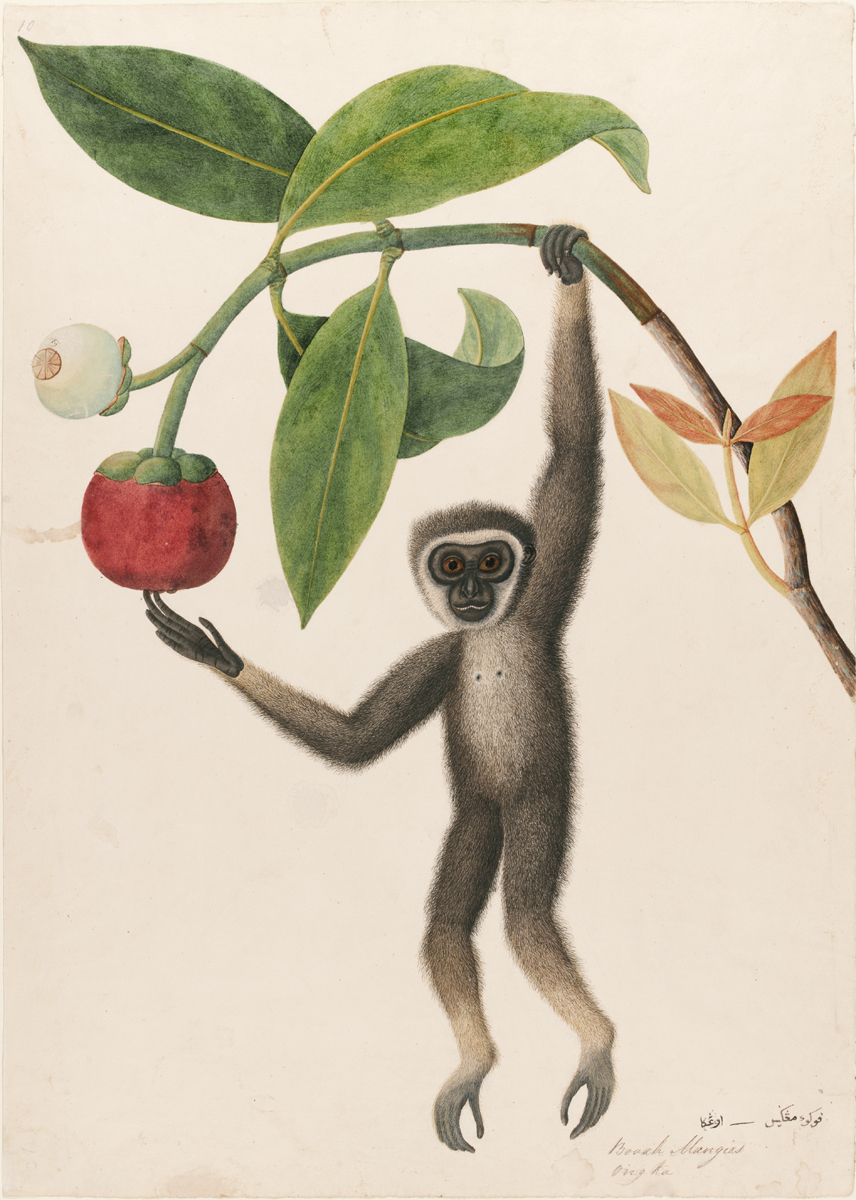

In addition, certain prominent details, which can be interpreted as the artists’ mistakes or inadequacies,13 take on a different significance once we account for the art training they had received. Take for instance the drawing of the Dark-handed Gibbon.14 Here, the gibbon’s size is inaccurately depicted – his head is smaller than the ripe mangosteen on the branch from which he hangs.15 Yet this infamous “mistake” is also emblematic of a stylistic clash, where Farquhar’s Chinese artists had to reconcile the way they were trained to depict landscapes through axonometric perspectives with their clients’ demands to employ a linear, one-point perspective. 16

In a similar vein, the depiction of animals, such as the Greater Mousedeer,17 in landscapes that represented neither the Malay Peninsula nor their natural habitats,18 can be understood in terms of how these artists were trained to depict landscapes19 rather than a lack of attentiveness towards the subjects they were portraying.20

Crucially, Kwa notes how these drawings evince the artists’ creative struggles. Despite being trained to aspire towards more impressionistic styles that capture the essence of a subject, the artists were required to use more technical representational methods – techniques they ironically viewed as more “pedantic” and foundational – and would have used and practised primarily in service of developing their personal impressionistic styles.21

As Kwa surmises, “[their] struggle was compounded by their training to draw what they sensed and felt” — a notion that strongly echoes Berger’s theory on aesthetics — “rather than what they saw”.22 Though the drawings remain unsigned, stylistic details allow us to construct not just a sense of who these artists were but also their struggles, as they endeavoured to make art that could fulfil their commissioned tasks.

In stark contrast, the Diard and Duvaucel drawings are noticeably less embellished. The animals and plants are illustrated with accurate sizes and colours, and a pronounced lack of “landscapes or views of the original habitats of the animals and plants” strongly implies that they were meant for scientific study, rather than art.23 Even so, the artistic processes of these unnamed artists remain apparent, especially in the pieces that remain incomplete.

While indeed demonstrating the “pressure [the artists faced in the field] to record time-critical aspects of the animals, setting aside the drawings for later when they had time to complete them”,24 these uncompleted pieces — and recurring patterns in how they are incomplete — provide valuable insight into their artistic processes, and by extension, their encounters with nature.

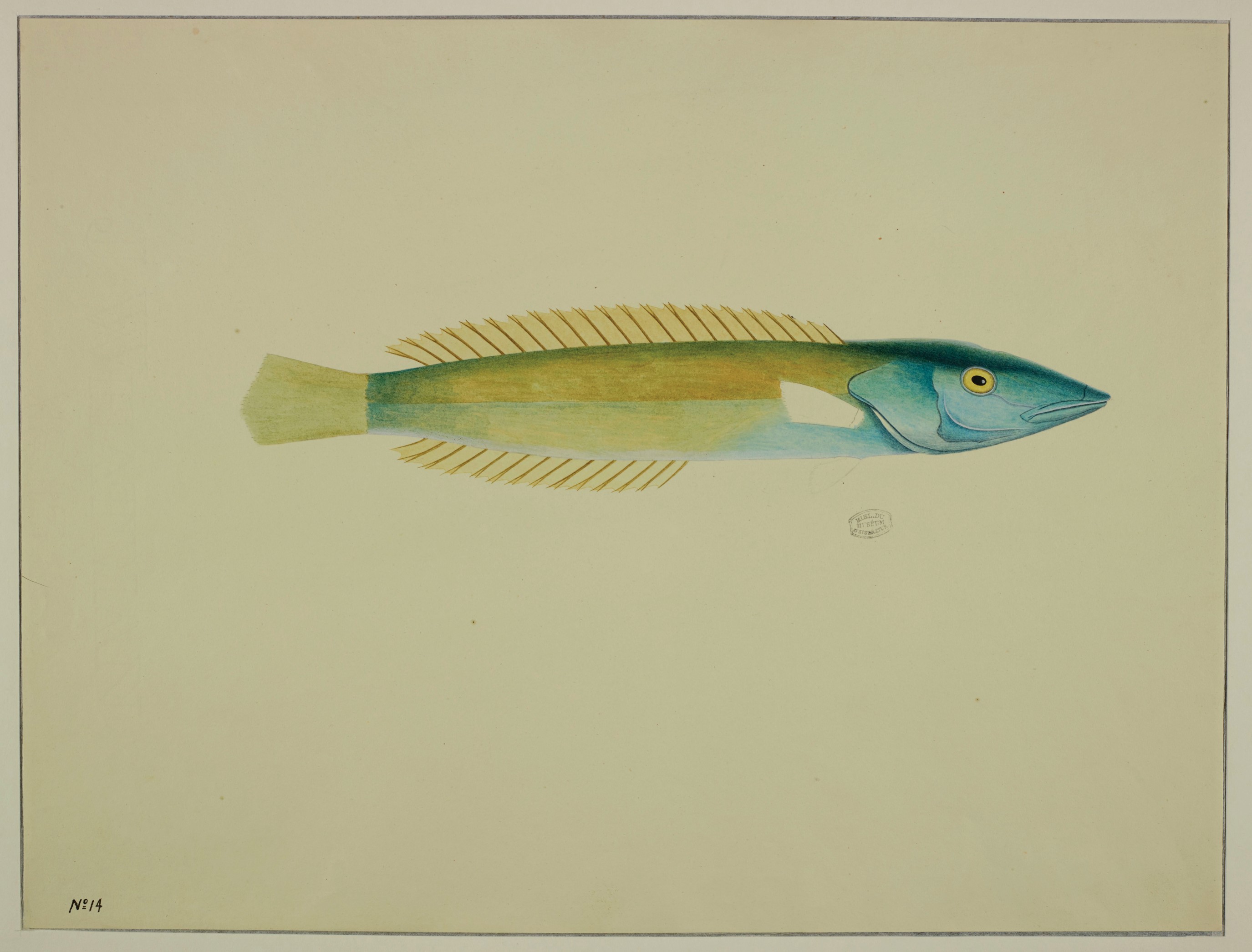

Missing Details

In my poem “About the Painters”, I linger on these uncompleted details, connecting with the artists’ encounter with nature by creatively reimagining the conditions that might have led to certain artistic decisions. For instance, a specific kind of incompleteness pervades the collection in the form of omitted details, such as a missing iris,25 an uncoloured wing,26 a blank fin27 and missing spots on the wings of the Great Eggfly.28 In each case, the omitted detail is clearly indicated by clean watercolour outlines, occasionally with details sketched in pencil. Should we emulate Kwa’s approach, these stylistic consistencies across these omissions could suggest that these pieces were the work of one artist.

Reptiles and amphibians such as Kuhl’s Gliding Gecko,29 Flat-tailed House Gecko,30 Long-nosed Horned Frog31 and Giant River Toad32 are drawn at the top of their respective pages, leaving unnecessary unused space at the bottom of the page. Meanwhile, the other reptiles, like the rest of the drawings, are centred on the page.33 Again, we might reasonably wonder if these pieces were the work of one artist, and the rest of the reptiles another.

At the same time, verifying the number, not to say identities, of these artists is near impossible; poetry, as a medium, also cannot conclusively answer these queries. What we can wonder about, instead, are the conditions that might have led the artists to make certain artistic decisions. More pertinently, we can also wonder what encounters with nature might have caused them to deviate from their clients’ original instructions.

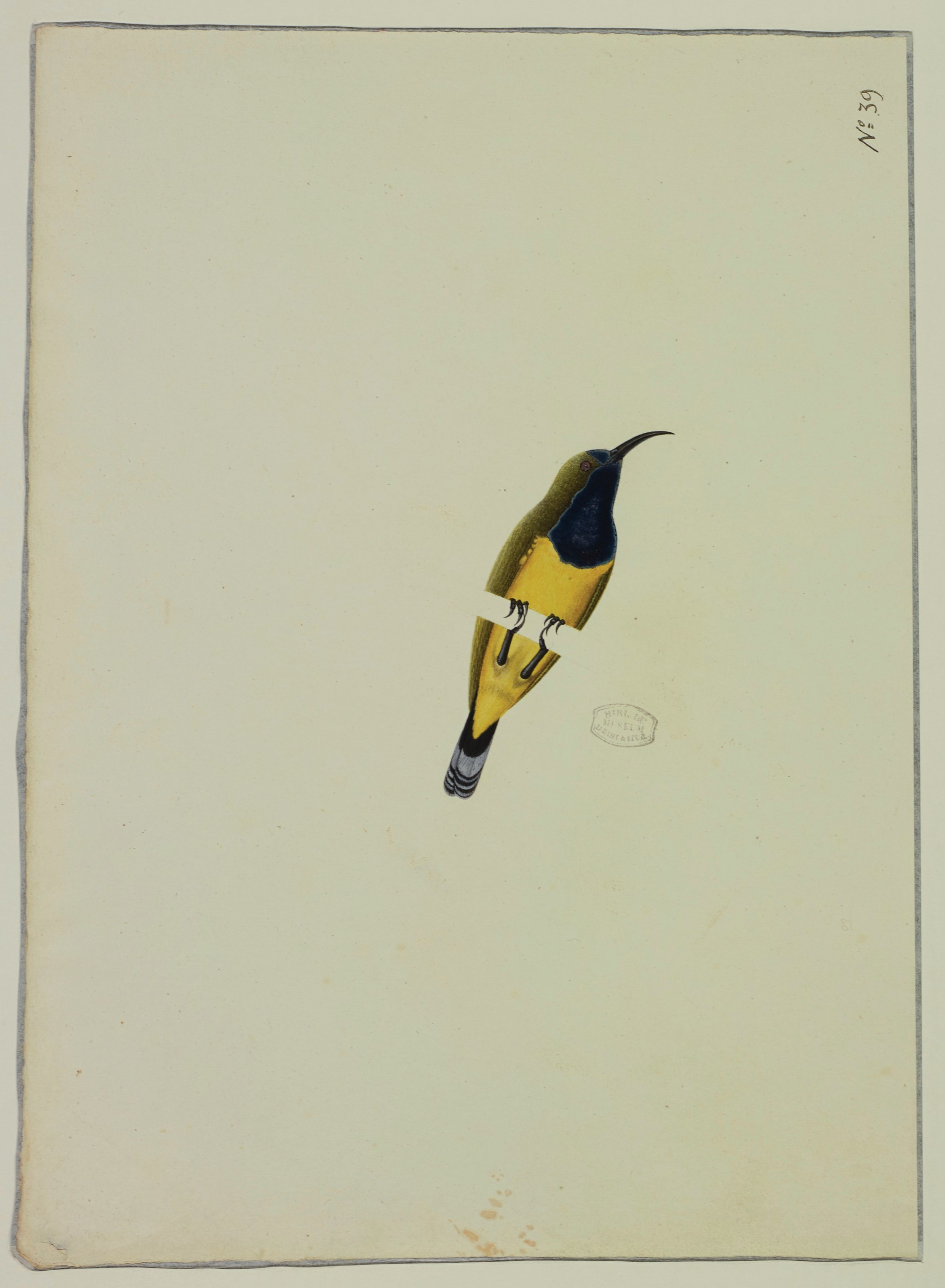

In one of the most noteworthy moments of artistic intent in the collection, we find some gesture towards an answer: in the drawing of the Olive-backed Sunbird,34 a strange gap with clean edges cuts through the bird’s midsection. This gap also occurs in the drawing of the Pink-necked Green Pigeon,35 suggesting the artist’s intention to add a branch later on.36 Branches in other forms appear across the collection, whether suggested by the pronounced curvature of birds’ claws,37 or the presence of actual branches sketched into other drawings.38 In the drawing of the Malay Brown Barbet, we even see the clear outline of a tree.39

What is precisely so noteworthy about the drawings of the Olive-backed Sunbird and the Pink-necked Green Pigeon goes beyond the existence of landscape features in a collection known to omit such details.40 Rather, in these two drawings, an external detail blocks our full view of the bird. Although this detail may better reflect the actual experience of birdwatching, this was not the goal of these illustrations, which were supposed to be as accurate as possible.41 Instead, the artist decided to not only add a branch, already a superfluous detail, but in a manner that prevents the bird from being portrayed in full. While we can simply consider this illustration as incomplete, we should also ask why the artist made this creative choice that clashed with the intended goals of the drawing.

Notice how the Olive-backed Sunbird is depicted, such that we are looking up at the bird amongst the branches, up in a tree. The answer perhaps lies in this salient visual composition, which is unique to this drawing in the collection.

More so than the artist’s identity, their artistic choice in this drawing brings us into the moment with them, experiencing the aesthetic emotion they felt in this human-nature encounter. These very moments, which my poem “About the Painters” lingers on, are part of the legacy left behind by these unnamed artists, which we should draw inspiration from and attend to in our daily lives.

Chrystal Ho is a writer from Singapore. She works primarily with poetry and nonfiction, with a keen interest in myth and ecological narratives. A former Creative Resident with the National Library (2022/23), she is currently pursuing a Masters in English (Creative Writing) at the Nanyang Technological University of Singapore.

Chrystal Ho is a writer from Singapore. She works primarily with poetry and nonfiction, with a keen interest in myth and ecological narratives. A former Creative Resident with the National Library (2022/23), she is currently pursuing a Masters in English (Creative Writing) at the Nanyang Technological University of Singapore.Notes

-

Clément Oury, “Diard, Duvaucel and the Muséum Nationelle d’Histoire Naturelle,” in Diard & Duvaucel: French Natural History Drawings of Singapore and Southeast Asia, 1818–1820, ed. Francis Dorai and Martyn E.Y. Low (Singapore: Embassy of France and National Library Board in partnership with Epigram Books, 2021), 26. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 508.0222 DIA) ↩

-

Oury, “Diard, Duvaucel and the Muséum Nationelle d’Histoire Naturelle,” 26–27. Although artists employed in such contexts are often referred to as “draftsmen” in various sources, I use the term “artists” to acknowledge their creative involvement in these natural history drawings. ↩

-

Francis Dorai and Martyn E. Y. Low, eds., Diard & Duvaucel: French Natural History Drawings of Singapore and Southeast Asia, 1818–1820 (Singapore: Embassy of France and National Library Board in partnership with Epigram Books, 2021). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 508.0222 DIA) ↩

-

Oury, “Diard, Duvaucel and the Muséum Nationelle d’Histoire Naturelle,” 30, 33. In addition to the artists, the identities of many others who contributed to these expeditions, such as the local collectors and taxidermists whom Diard and Duvaucel hired, were also not documented. ↩

-

Martyn E. Y. Low, Kelvin K. P. Lim and Peter K. L. Ng, “The First Singapore Biodiversity Expedition: The Legacy of Pierre-Médard Diard and Alfred Duvaucel,” in Diard & Duvaucel: French Natural History Drawings of Singapore and Southeast Asia, 1818–1820, ed. Francis Dorai and Martyn E.Y. Low (Singapore: Embassy of France and National Library Board in partnership with Epigram Books, 2021), 50. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 508.0222 DIA) ↩

-

John Berger, “The White Bird,” in Why Look at Animals? (London: Penguin Books, 2009), 59. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. 113.8 BER) ↩

-

Berger, “The White Bird,” 57. Berger emphasises just how unexpected the presence of beauty is in nature by highlighting how “nature is energy and struggle”. Against this backdrop of nature’s hostility towards life and humankind, “beauty is always an exception, always in despite of. This is why it moves us.” ↩

-

Berger, “The White Bird,” 59. ↩

-

Berger, “The White Bird,” 60. ↩

-

Kees Rookmaaker, “The Diard and Duvaucel Collection of Drawings,” in Diard & Duvaucel: French Natural History Drawings of Singapore and Southeast Asia, 1818–1820, ed. Francis Dorai and Martyn E.Y. Low (Singapore: Embassy of France and National Library Board in partnership with Epigram Books, 2021), 54. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 508.0222 DIA ↩

-

Low, Lim and Ng, “The First Singapore Biodiversity Expedition,” 50. ↩

-

Kwa Chong Guan, “Drawing Nature in the East Indies: Framing Farquhar’s Natural History Drawings,” in William Farquhar et al., Natural History Drawings: The Complete William Farquhar Collection: Malay Peninsula, 1803–1818 (Singapore: Editions Didier Millet: National Museum of Singapore, 2010), 325. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 759.959 NAT) ↩

-

Kwa, “Drawing Nature in the East Indies,” 321. Kwa notes that Raffles and others often took issue with ‘“stiffness” and “flatness” […] in the drawings of the Chinese artists”. ↩

-

William Farquhar et al., Natural History Drawings: The Complete William Farquhar Collection: Malay Peninsula, 1803–1818 (Singapore: Editions Didier Millet: National Museum of Singapore, 2010), 252. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 759.959 NAT) ↩

-

Kwa, “Drawing Nature in the East Indies,” 322. ↩

-

Kwa, “Drawing Nature in the East Indies,” 321. Axonometric perspectives, in contrast to one-point perspectives, employ “no vanishing point[s] and, hence, no optical distortion”. As Kwa observes, for Chinese artists, such a method was well suited to depict “the long landscapes [they] painted, for with it [they] could shift and move [their] perspective […] Axonometry made Chinese art scrollable”. ↩

-

Farquhar, et al., Natural History Drawings, 266. ↩

-

Kwa, “Drawing Nature in the East Indies,” 322. For instance, some of the animals were depicted “in the center of a landscape of rocks and windswept grass and/or bushes and sand”. ↩

-

For instance, the Chinese artists were trained to develop their own personal style of depicting rocks, based on the understanding that “the ability to capture the qi, or the essence of a rock, is essential to the drawing of a landscape” (322). This aspect of their artistic training accounts for the use of rock landscapes as backdrops in their paintings, even if the animals did not actually live in such habitats. ↩

-

Kwa, “Drawing Nature in the East Indies,” 322. ↩

-

Kwa, “Drawing Nature in the East Indies,” 321. While the preferred painting style of these Chinese artists can be likened to Western impressionism, the use of “impressionistic” in this essay does not refer to this style. Here, “impressionistic” refers to the “ink-play”, or xieyi style that the artists practicsed, which focuses on conveying the essence of their subject. In contrast, the more technical style required by clients like Farquhar, is similar to what the artists considered the fundamentals of painting: brushwork, or gongbi. ↩

-

Kwa, “Drawing Nature in the East Indies,” 327. ↩

-

Rookmaaker, “The Diard and Duvaucel Collection of Drawings,” 54. ↩

-

Low, Lim and Ng, “The First Singapore Biodiversity Expedition,” 49. ↩

-

See Dorai and Low, Diard and Duvaucel, “No 23: Malay Brown Barbet”, 110, and “No 54: Black Magpie”, 143. ↩

-

Dorai and Low, Diard and Duvaucel, “No 54: Black Magpie”, 143. Besides an incomplete wing and iris, the Black Magpie also has a missing leg. ↩

-

Dorai and Low, Diard and Duvaucel, “No 14: Cigar Wrasse”, 172. ↩

-

Dorai and Low, Diard and Duvaucel, “No 5: Great Eggfly”, 174. ↩

-

Dorai and Low, Diard and Duvaucel, “No 4: Kuhl’s Gliding Gecko”, 158. ↩

-

Dorai and Low, Diard and Duvaucel, “No 5: Flat-tailed House Gecko”, 159. ↩

-

Dorai and Low, Diard and Duvaucel, “No 7: Long-nosed Horned Frog”” 170. ↩

-

Dorai and Low, Diard and Duvaucel, “No 6: Giant River Toad”, 171. ↩

-

The collection holds only two amphibians: the Long-nosed Horned Frog and Giant River Toad. In the absence of other amphibian drawings, I compared the four drawings discussed in this section to the other reptile drawings instead. ↩

-

Dorai and Low, Diard and Duvaucel, “No 39: Olive-backed Sunbird”, 150. ↩

-

Dorai and Low, Diard and Duvaucel, “No 50: Pink-necked Green Pigeon”, 66. ↩

-

Rookmaaker, “Diard and Duvaucel Collection of Drawings,” 66. ↩

-

See, for instance, Dorai and Low, Diard and Duvaucel, “No 49: Jambu Fruit Dove”, 65; “No 51: Little Green Pigeon”, 68; and “No 55: Green-spectacled Green Pigeon”, 70–71. ↩

-

See, for instance, Dorai and Low, Diard and Duvaucel, “No 64: Pied Cuckoo”, 72; “No 71b: Scarlet-rumped Trogon”, 108–9; and “No 42: Small Minivet”, 136. Note how the branches, especially in the latter two, are relatively detailed and cannot simply be passed off as guiding lines. The branch that the Scarlet-rumped Trogon is perched on even includes two leaves. ↩

-

Rookmaaker, “Diard and Duvaucel Collection of Drawings,” “No 23: Malay Brown Barbet”, 110. As mentioned earlier, the iris of the bird is incomplete. ↩

-

Rookmaaker, “Diard and Duvaucel Collection of Drawings,” 54. ↩

-

Rookmaaker, “Diard and Duvaucel Collection of Drawings.” ↩