Tools of the Trade: Letterpress Printing in Singapore

Letterpress printing may be obsolete today but the tools involved continue to be objects of fascination.

The history of printing in Singapore goes back about 200 years when Christian missionaries first arrived in the region and introduced the technology – letterpress printing – with the aim of spreading the gospel.

A form of relief printing where ink is applied to a raised surface which is then pressed onto paper, letterpress printing was the main commercial method for printing books and newspapers until the late 20th century. It was eventually overtaken by newer commercial printing technologies that were more efficient and economical.

This article showcases some of the letterpress printing equipment used here between the 1950s and 1980s. These pieces of equipment from a bygone era were salvaged by Sun Yao Yu, founder of Typesettingsg, a studio he set up in 2014 to preserve and document Singapore’s printing heritage. From hand-carved wooden type to manually operated presses, these items showcase the technology and craftsmanship that once formed the backbone of Singapore’s printing industry.

Sun Yao Yu, a traditional letterpress educator and Typesettingsg’s founder. Courtesy of Sun Yao Yu.

Sun Yao Yu, a traditional letterpress educator and Typesettingsg’s founder. Courtesy of Sun Yao Yu.Wood Type

Wood has been widely used to print letterforms and illustrations for centuries. In China and Europe, woodblock printing precedes printing with wood type. In Singapore, most wood type was hand-carved by craftsmen locally, using cheap and lightweight wood. For increased durability, end-grain hardwood is used when mass-producing wood type.

Wood type was used mainly for large format prints like posters, as metal type was rarely cast in such large sizes and were expensive to produce. This made wood type more affordable and accessible.

Pictured here are wood type from the 1980s from Yu Yi Rubber Stamp & Print, which ceased operations in 2017.

Pictured here are wood type from the 1980s from Yu Yi Rubber Stamp & Print, which ceased operations in 2017. Metal Type Sorts

A sort or type is a block with a letter or character cast from a mould called a matrix.

Sorts are manually arranged into words and lines to make up a forme, which is the locked-up arrangement of type used for printing. This durable and reusable metal type allowed printers to create consistent and high-quality printed materials.

This font, Palace Script in 14 pt, was cast in 1971 and sold by a local printing equipment trading company, Raman & Co. In the 1980s, metal type like these were still sold to local print shops like Jetprint Services, where this was salvaged from.

This font, Palace Script in 14 pt, was cast in 1971 and sold by a local printing equipment trading company, Raman & Co. In the 1980s, metal type like these were still sold to local print shops like Jetprint Services, where this was salvaged from. Matrices

A matrix is a mould used to cast the printing surface of a sort or type. To create the face of the type, a casting machine pumps molten type metal into the recess of a matrix.

To create different sizes for each character, a matrix for each size is used. Some of the more common sizes, when converted from the Chinese sizing system to the point system, are 63 pt, 36 pt, 28 pt, 21 pt, 15.75 pt, 14 pt, 10.5 pt, 7.875 pt and 6 pt.

In Singapore, the casting of both simplified and traditional Chinese type was still carried out in the 1980s.

Pictured here is the matrix for the Chinese character 短 (short) in 宋体 (serif). Common typefaces used locally include 宋体 (serif), 黑体 (sans serif) and 楷体 (script). It is possibly among the last few surviving matrices in Singapore, and was salvaged from Odds ‘N’ Collectables, a local heritage shop.

Pictured here is the matrix for the Chinese character 短 (short) in 宋体 (serif). Common typefaces used locally include 宋体 (serif), 黑体 (sans serif) and 楷体 (script). It is possibly among the last few surviving matrices in Singapore, and was salvaged from Odds ‘N’ Collectables, a local heritage shop. Type Cases

Type cases are compartmentalised wooden trays used to organise movable type. The trays are stored vertically, and cases can vary in size and layout. Each tray would come with a label indicating the typeface and font size.

Type could be organised according to common standards. A California job case, for example, has 89 compartments. Lowercase letters and punctuation are stored on the left, uppercase letters on the right, and numerals and symbols at the top. Lowercase letters that are used most frequently, such as ‘e’, are placed within easy reach and given larger compartments. The compartments for uppercase letters are uniform in size and arranged alphabetically, with the exception of ‘J’ and ‘U’. These are placed after ‘Z’ as they were not part of the alphabet used by early English printers and were only introduced in the 16th century.

The type cases here were salvaged from Seng Huat Press, which shut down in 2023.

The type cases here were salvaged from Seng Huat Press, which shut down in 2023. The Government Printing Office was established around 1861 under the jurisdiction of the Public Works Department. It was responsible for printing works such as Government Gazettes, Bills, Ordinances, School and Government examination papers, Legislative Assembly debates, official forms, revenue receipts, account books, registers, invitation cards, publicity posters, booklets and pamphlets.

On 1 July 1973, the printing office became a private printing company and was subsequently renamed Singapore National Printers (Pte) Ltd. It was acquired by Toppan Holdings in 2008. Today, the company is known as Toppan Next Pte. Ltd.

Type cases and cabinets shown during Yusof Ishak’s tour of the Government Printing Office, 1961. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Type cases and cabinets shown during Yusof Ishak’s tour of the Government Printing Office, 1961. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Lead and Rule Cutters

Leads are thin strips of lead used between lines of type, while rules are type-high strips of lead or brass used for printing borders or lines.

Leads and rules are usually sold at standard pre-cut lengths, but may be cut to their desired lengths to fit snugly in a composing stick or chase using a lead and rule cutter like the one below.

Depending on the model, a lead and rule cutter may come with two knives – one in front for cutting leads, and another behind it for cutting rules. The lead knife is parallel to its opposing edge, which cuts the lead squarely, while the rule knife sits at an angle from its opposing edge and cuts like a shear.

Universal Notting London Lead and rule cutter. Cutters like these are a rarity today, with only a handful still being used in old print shops. This cutter was from Yu Yi Press Company.

Universal Notting London Lead and rule cutter. Cutters like these are a rarity today, with only a handful still being used in old print shops. This cutter was from Yu Yi Press Company.Formes

When setting type by hand, lines of type are moved from the composing stick to the galley – metal trays where type is laid and tightened into place with printer’s string. This locked arrangement or composition of type and spacing material from which prints are made is called a forme.

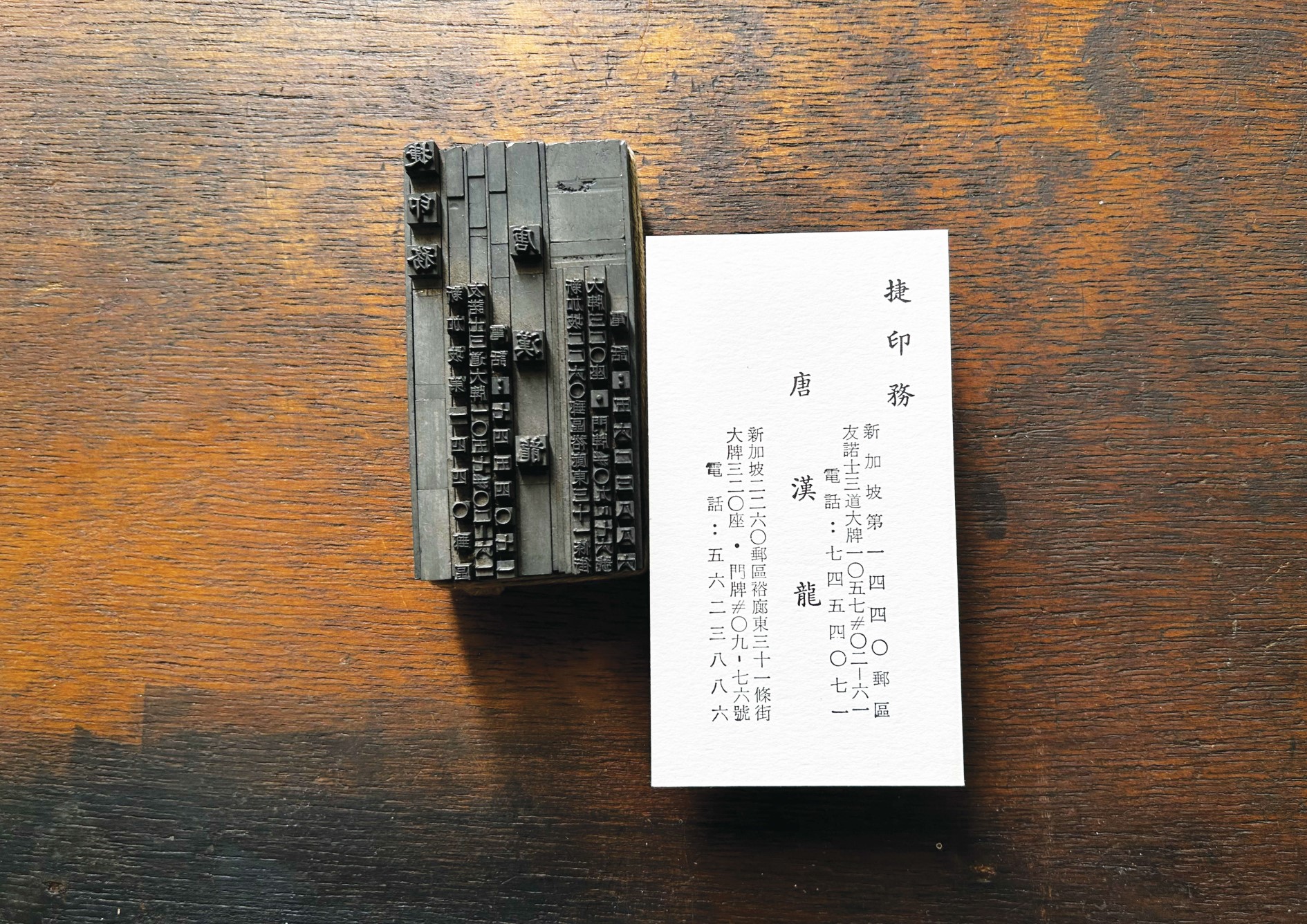

The photo below shows a forme for a name card that contains both the information of the client (leftmost side of the printed card) and the print shop (right). To reduce the time taken for typesetting, formes that are frequently used for reprints may be left assembled, like this one from Jetprint Services.

Forme for a Chinese name card, early 1980s.

Forme for a Chinese name card, early 1980s.Flongs

For the most part, as it was impractical for printers to keep their type, leads, furniture and chases locked as formes for a single project, stereotype plates created from temporary moulds or matrices called flongs were used instead.

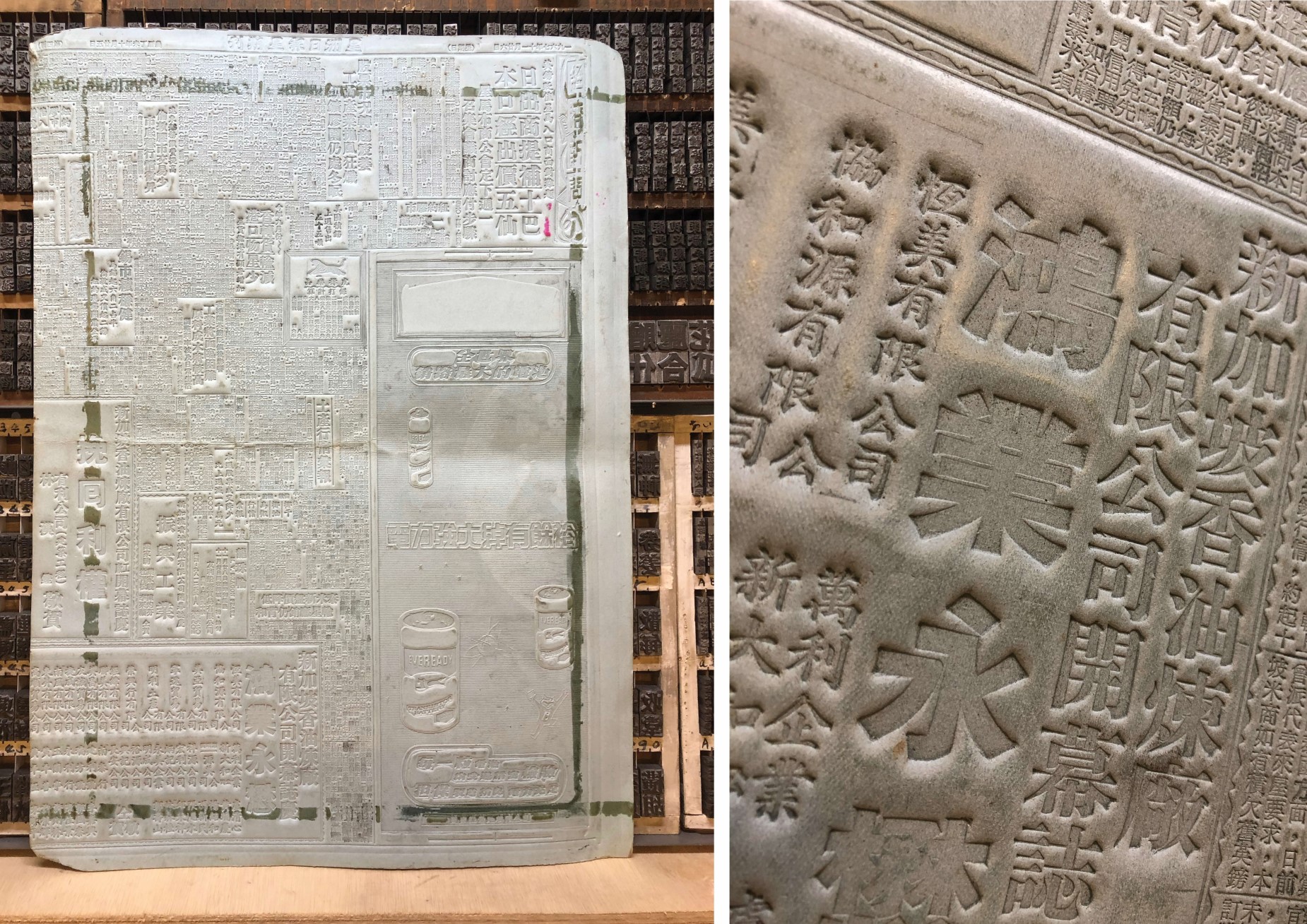

A flong is made by pressing papier-mâché over a forme. The flong is then used as a mould to cast a stereotype plate from hot metal. Stereotype plates kept type from wearing down and were widely used for short-lived tasks such as newspaper and advertising printing. After printing, flongs were burnt and stereotypes were melted down to plate metal to be reused.

Flong for Sin Chew Daily (星洲日报), 1967.

Flong for Sin Chew Daily (星洲日报), 1967.Typesetting Machines and Printing Presses

Although printing presses were reaching incredible speeds, typesetting remained a slow and labour-intensive process. Type had to be individually cast in moulds and assembled manually in composing sticks, then re-sorted back into their type cases after they were used.

First manufactured in 1886, Linotype machines greatly sped up the typesetting process. Within a single machine, moulds or matrices could be assembled into a line then cast using molten metal into a single piece bearing a line of text called a slug. The process of using molten metal to create sorts or slugs for printing was referred to as hot metal typesetting. Linotype machines could also return the matrices back to their respective magazines after casting the slugs.

Linotype casting machines at the Government Printing Office, 1952. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

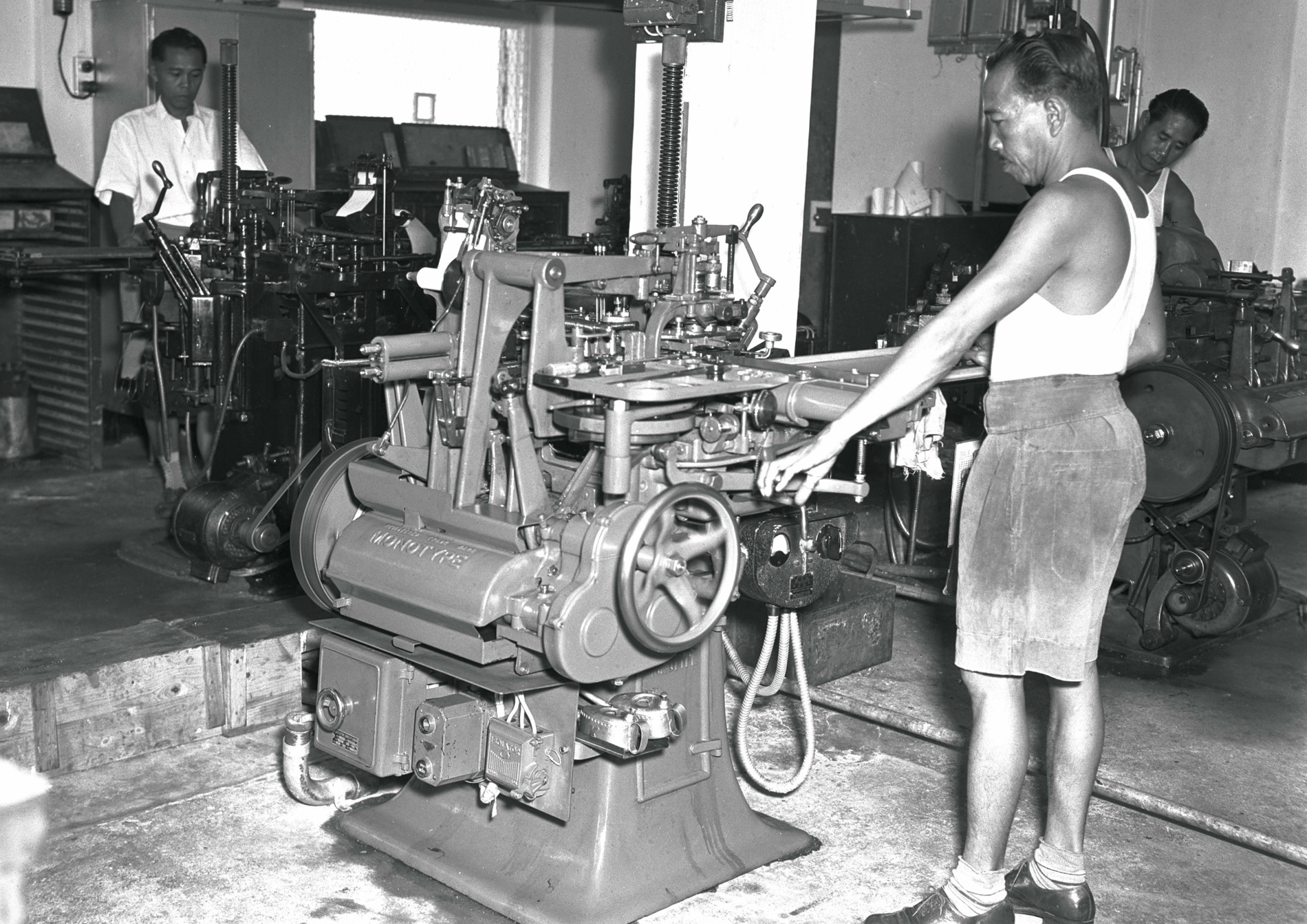

Linotype casting machines at the Government Printing Office, 1952. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The Monotype caster was part of the Monotype system, which included a separate Monotype keyboard. Similar to Linotype machines, this system was used in hot metal typesetting. But unlike Linotype machines that cast a larger slug, or a single line of type for printing, Monotype systems cast individual letters of type instead, which made corrections and changes easier.

Both the Monotype and Linotype systems were innovations based on the same goal of creating formes quickly that did not have to be painstakingly sorted for re-use.

Monotype caster used at the Government Printing Office, 1952. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Monotype caster used at the Government Printing Office, 1952. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The Heidelberg press was famed for its speed and efficiency, thanks to its revolutionary design. Its double-sided rotating feeder arm, a feature not found in other printing presses of its time, removed the need for paper to be manually fed to and from the machine. Since print operators no longer needed to position, hold and remove the paper for each print job, newer models of the printing press could print at increasingly faster speeds. The printing press also came with an ink reservoir, which removed the need to ink the rollers – another feature not found in other printing presses of that era.

Heidelberg cylinder press at the Singapore National Printer’s General Printing Office, 1975. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Heidelberg cylinder press at the Singapore National Printer’s General Printing Office, 1975. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Popular with hobbyists today, table-top platen presses are operated manually to print items like business cards and invites. Before printing, ink is deposited on the disk and evenly distributed on its surface by rollers when the handle is repeatedly pressed down and released. After the ink is evenly spread and the handle is in its resting position with the clamshell platen open, the forme and paper are put in place.

To start the printing process, the handle is firmly pressed down once. This recharges the rollers with ink, transfers the ink to the forme, and closes the platen, bringing the paper into contact with the forme. Releasing the handle reopens the platen, and the printed sheet can be removed and replaced with a fresh sheet.

Adana 8 x 5 printing presses. These printing presses were salvaged from various print shops in Singapore that have shuttered.

Adana 8 x 5 printing presses. These printing presses were salvaged from various print shops in Singapore that have shuttered.Type Specimen Books and Printing Blocks

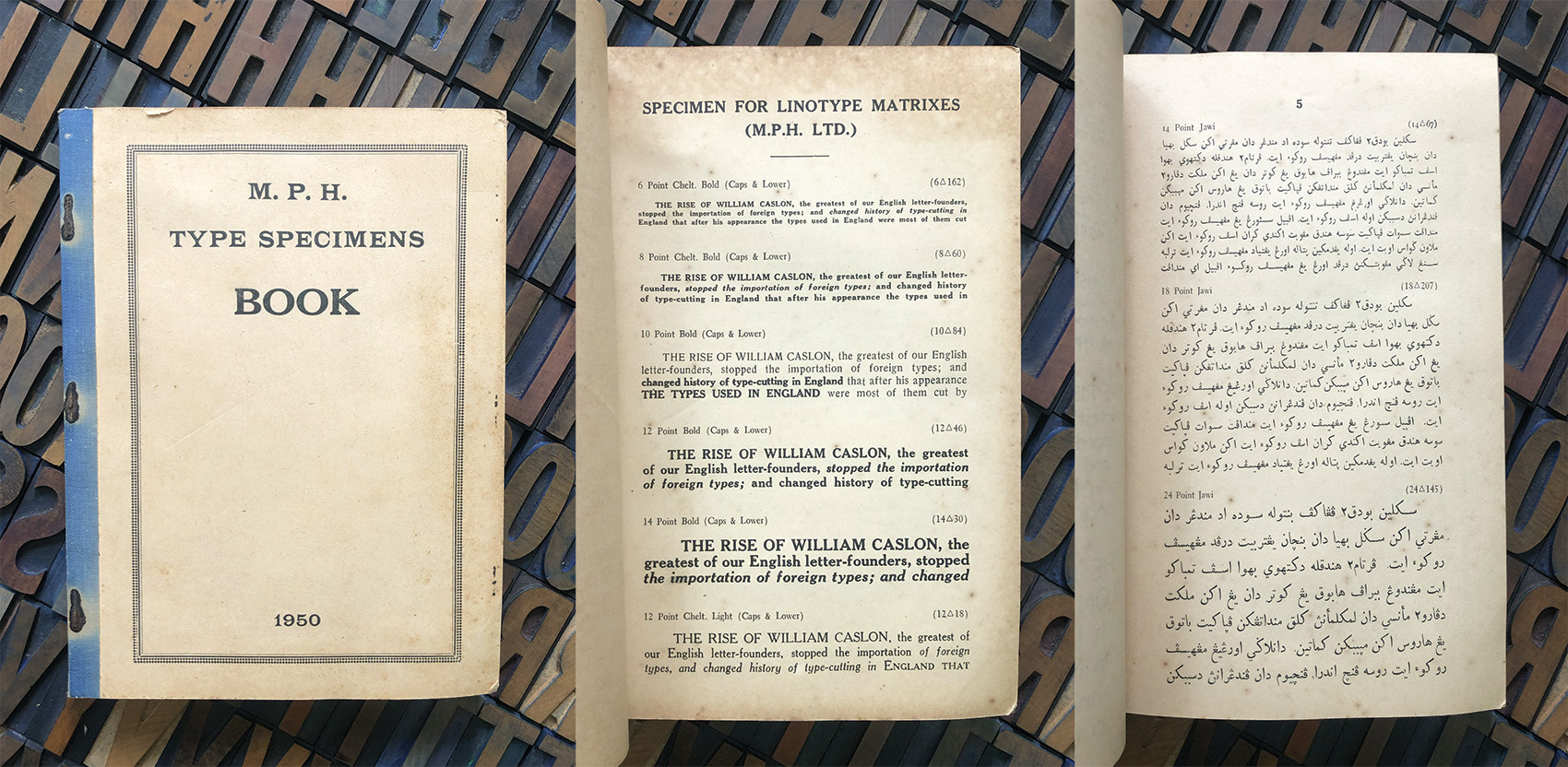

Type specimen books contain collections of typefaces and design layout examples, and are used to demonstrate a printer’s services and capabilities.

The MPH type specimen book below showcases Linotype, monotype and wood type faces, and includes a rare Jawi script specimen. It is likely the only surviving copy of the 1950 edition and was salvaged from a local heritage shop in Fook Hai Building.

MPH type specimen book, 1950.

MPH type specimen book, 1950.MPH was originally established in 1890 by William Girdlestone Shellabear, a Methodist missionary and former army officer. It was first known as Amelia Bishop Press, then American Mission Press, before it was renamed Methodist Publishing House in 1906. It changed its name to Malaya Publishing House in 1927 and then to Malaysia Publishing House in 1963.

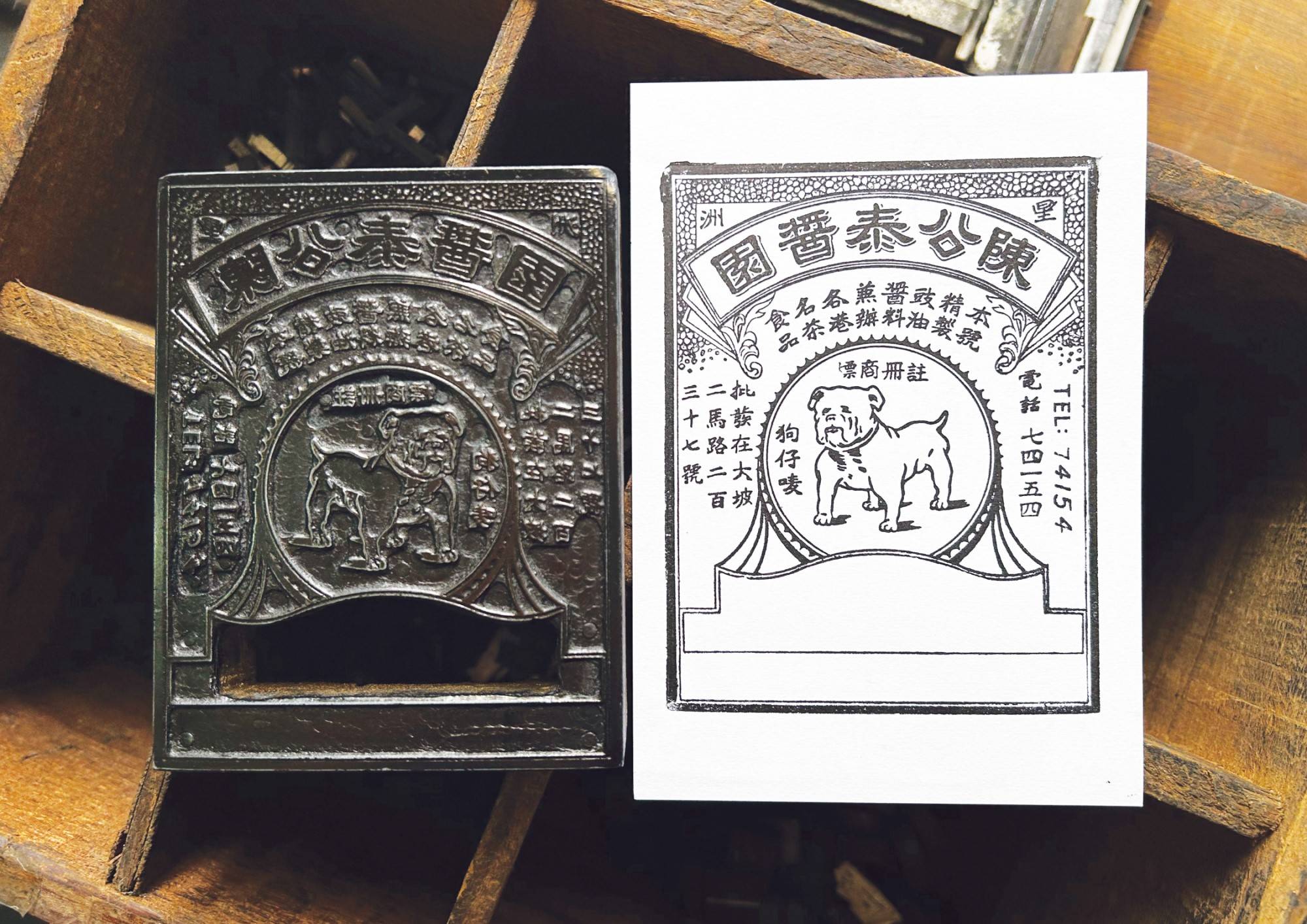

The printing block below with Chan Kong Thye’s branding was used to print bottle labels in the 1970s. It is likely the only surviving printing block with this design and branding.

Printing block for a bottle label with Chan Kong Thye’s branding, 1970.

Printing block for a bottle label with Chan Kong Thye’s branding, 1970.Printing blocks are often made using zinc, magnesium or brass plates. The plate is combined with a wooden base to bring the printing surface to the standard type height of 0.918 inch.

To produce a label in colour, multiple printing blocks were created for each colour based on the CMYK colour model. Each block is then precisely aligned and used separately on the printing press, with the different colours printed in quick succession to produce secondary colours.

The brand can still be found today in supermarkets like NTUC. Photo by Veronica Chee.

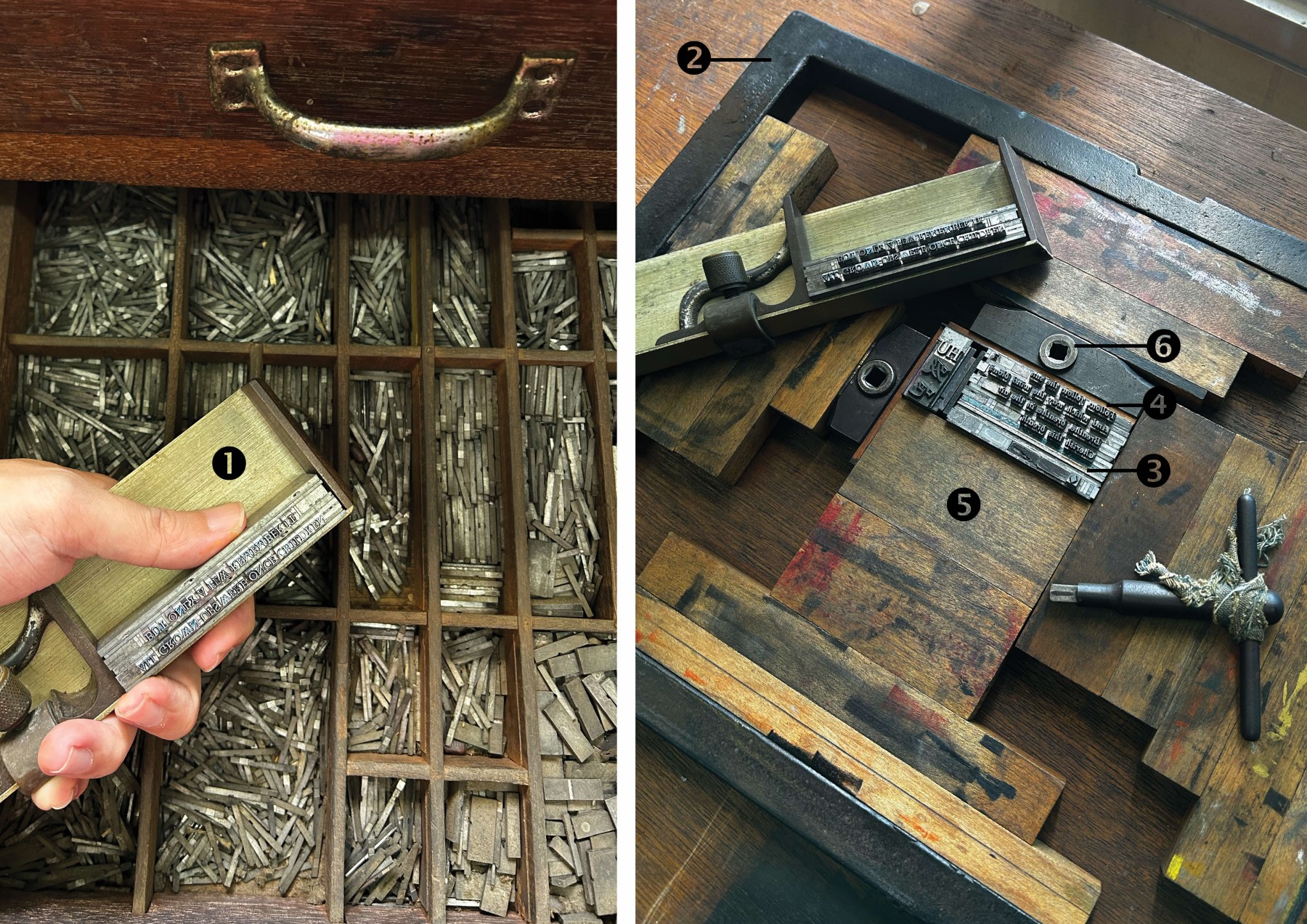

The brand can still be found today in supermarkets like NTUC. Photo by Veronica Chee.A typesetter, who arranges type for printing, would use tools such as the following to lay out type:

-

1. Composing stick - a tray-like tool with an adjustable slide used to arrange metal type into words and lines when setting type by hand; each type is placed upside down, from left to right

2. Chase - a heavy metal frame used to hold type in place; the size of a chase is matched to a specific press

3. Lead/Slug - a thin strip of metal used to produce the spacing between lines

4. Reglets - wooden spacers used to create larger gaps between lines and paragraphs

5. Furniture - largest spacing material made of wood or metal, used to surround the type to hold it in place

6. Quoins - a clamp-like device tightened with a key to lock the type in place within a chase; typically, at least two are used – one to secure the type vertically and the other horizontally

Unless otherwise stated, the photos in this collection are courtesy of Sun Yao Yu. Yao Yu is a traditional letterpress educator and a founding member of the International Association of Printing Museums.

Further Readings

British Letterpress

https://britishletterpress.co.uk/

Colclough, Joanna. “The Linotype: The Machine that Revolutionized Movable Type.” Library of Congress Blogs, 8 June 2022. https://blogs.loc.gov/headlinesandheroes/2022/06the-linotype-the-machine-that-revolutionized-movable-type/.

Fleishman, Glenn. “Flong Time, No See: How a Paper Mold Transformed the Growth of Newspapers.” Medium, 25 April 2019. https://glennf.medium.com/flong-time-no-see-2b54438027dd.

Letterpress Commons

https://letterpresscommons.com

Melbourne Museum of Printing

https://www.mmop.org.au/showroom/show03.htm

Straits Times, “The New Malay Linotype.” 10 July 1924, 9. (From NewspaperSG)