Multilingualism as Utopia: Linguistic Citizenship in 1950s Malayan Writing

By Lee Tong King

The 1950s was a decade of radical transformation in Malaya. In the aftermath of the Japanese Occupation (1942–45) and before the idea of political independence from colonial rule became reality, Malaya, including Singapore, was embroiled in the rise of anti-colonial sentiments and British suppression of communist insurgencies. This culminated in the promulgation of the Emergency Act in June 1948, which remained in effect till July 1960.1

In the intervening years, Malaya’s sociopolitical landscape was mired in ideological tensions and armed conflict. Precisely due to these tensions, a nascent Malayan consciousness began to take shape, with important implications for literary and cultural activities. More specifically, this period of extraordinary flux in identity incubated the notion of a distinctive Malayan literature and culture, a hitherto nonexistent category, thereby opening the way to a vibrant tradition of creative writing in the region.

This article looks at two parallel developments in the Chinese-language and English-language literary circles during this period. Both involved multilingual innovation in the written language, namely the infusion of Chinese dialects in Sinophone fiction and the mixing of resources from English, Malay and Chinese in Anglophone poetry. The article traces the ideological circumstances behind these developments and examines the historical significance of these multilingual experiments in terms of how they articulate the sociopolitical aspirations of intellectuals in those turbulent times.

Uniqueness of Malayan Chinese Literature

As an important conduit of expression, literature bloomed in postwar Malaya, at a time when people were seeking to invent an imagined geopolitical community2 in which to position themselves beyond the colonial grid. It is unsurprising, therefore, that literary writing proliferated in the 1950s, in contrast to its relative paucity in the 1940s; indeed, as far as Chinese-language literature was concerned at least, the 1950s was a more spirited period than the 1960s.3 This was the decade when Chinese fiction writers in Malaya became increasingly experimental with their language medium, which was by convention a standard written Chinese based on the Mandarin vernacular hailing from the 1919 May Fourth Movement in China.

As we will see, instead of featuring only the standard language, Chinese fiction of this period was marked by bits and pieces of Chinese dialects and colloquial Malay. Prior to this, these latter tongues belonged to the streets and were not seen as legitimate registers for literary writing among Malayan Chinese authors. The backdrop to such experimentation was a polemic, dubbed as the Great Debate, that occurred between December 1947 and April 1948. This took the form of a “paper war” across literary supplements of several major Chinese newspapers of the time, such as Sin Chew Jit Poh, Nan Chiau Jit Pao and Min Sheng Pau. Two camps of writers, the Malayan-Chinese Literature School and the Overseas-Chinese Literature School,4 expressed opposing stances around the contentious idea of the “uniqueness of Malayan Chinese literature”.

The first group believed that the Chinese literature of Malaya should be distinct from that of China, as each developed under very different sociopolitical circumstances. The latter group, comprising the so-called immigrant writers (writers from China who sojourned in Malaya), sometimes derogatorily called refugee writers, insisted that Malayan Chinese literature was but a diasporic offshoot of Chinese literature from China and thus was not fundamentally unique.5

Twenty-five articles were exchanged in this debate, including some by a minority of contributors who sat on the fence. The jury is out as to which camp “won” the debate – though there seems to be a degree of consensus among scholars that the Malayan School took dominance, although renowned historian Wang Gungwu opined that the Overseas-Chinese School had been victorious. Wang felt that the Malayan-Chinese School lost out “not because of lack of support among writers – in fact, the young, the local-born, supported them wholeheartedly. But they lost because the newspapers and publishers were dominated by men who insisted that all their writing should be seen as tributaries of the main river of literature of China”.6

This divergence in opinion may be attributed to the fact that precisely what counts as winning or losing is far from clear. On the face of the evidence, however, Wang’s retrospective assessment is slightly curious for two reasons. First, as mentioned earlier, the articles constituting the Great Debate were published in the literary supplements of leading Chinese newspapers, which means the Malayan-Chinese School was not at all deprived of media space to communicate their position, notwithstanding the stance of the newspaper editors.

Second, in a matter of years, the Overseas-Chinese School had all but disappeared from the local literary scene. The advocates of the “uniqueness of Malayan Chinese literature” eventually prevailed due to historical contingencies. After the British declared a state of emergency in Malaya in June 1948, the immigrant writers either voluntarily returned or were repatriated to China.7 Strict controls over imported reading material from China were imposed under the Emergency Regulations Ordinance (1948). The Ordinance entailed the Emergency (Publications–Import Control) Regulations and the Emergency (Publications–Control of Sale and Circulation) Regulations.8 Clause 5(1) in the first set of Regulations declared that

“[t]he Controller and an authorised officer shall have power to detain, open and examine any article coming into the Federation [of Malaya] in any manner whatsoever from any place outside the Federation which a Controller or an authorised officer has reason to believe contains or consists of a publication (hereinafter in these Regulations called a “prejudicial publication”)–

(a) the importation of which is by reason of the existence of the state of

emergency prejudicial to the successful prosecution of measures taken in

the Federation [of Malaya] or in the Colony [of Singapore] to terminate the

emergency[.]” 9

And Clause 3(1) in the second set of Regulations uses a parallel wording in respect of the sale and circulation of material deemed politically sensitive. For the purposes of both Regulations, literary books and magazines from China would have counted as “prejudicial publications” that could potentially indoctrinate values detrimental to colonial interests. The upshot of the implementation of these Regulations was the creation of a vacuum in Chinese-language literature,10 compelling Malayan-Chinese writers to “seek their genius in themselves”.11 Hence the rise of Chinese-language writing speaks to locale-specific sensibilities in Malaya, partaking “a consolidation of localisation efforts to become ‘more Nanyang’.”12

Vernacular Voices in Chinese-Language Fiction

It is against this ideological background that a linguistic phenomenon of interest emerged among a new generation of Malayan-Chinese writers in the 1950s, namely the representation of Chinese dialects, and to a lesser extent colloquial Malay (also known as Bazaar Malay), in fictional works that are predominantly composed in standard written Chinese.

One of the most prolific writers in this period who put this technique into practice was Miao Xiu (1920–80). Born in Singapore, Miao Xiu participated in the Great Debate, contributing an article in Sin Chew Jit Poh on 28 February 1948 under the nom de plume Wen Renjun. In his article, Miao Xiu clearly expressed his support for the Malayan-Chinese Literature School.13 It is thus no surprise that his writing offers abundant traces of Chinese dialects and colloquial expressions (including vulgarities), for the use of place-based idiolects is one of the principal means through which the locale-specificity of Malayan Chinese literature was manifested. The expletive 丟那媽 (diu na ma, a condensed transliteration of a Cantonese expletive), for instance, often appears in the utterances of Miao Xiu’s working-class characters in his fiction and features as one of the “signature” terms in his linguistic repertoire.

Miao Xiu was not alone in this enterprise. He was joined by several contemporaries, notably Zhao Rong (1920–88), who also contributed to the Great Debate, under the pseudonym Xi Qiao. A strong advocate of the uniqueness of Malayan Chinese literature, Zhao published two articles in the Xing Chen supplement of Sin Chew Jit Poh in early 1948, one on 26 January14 and the other on 16 February.15 Like Miao Xiu, Zhao Rong was relatively liberal in his linguistic use from the vernaculars. A spectacular example is his 1958 short story “Old Stone Mountain”,16 the plot driven primarily by Cantonese-based dialogues, as represented by Cantonese characters that are graphically similar to but vary from standard Chinese characters. Here the overall proportion of Cantonese used is so high that readers unfamiliar with the Cantonese script and sound would conceivably have difficulty understanding the story based on the narrative segments (written in standard Chinese characters) alone.

By and large, however, the dialect segments in Chinese fiction from this period appear in dialogues, in apparent mimicry of the parole of ordinary folks on the streets, although traces of dialects occasionally found their way into the narrative. The most frequently featured dialect is Cantonese. Cantonese was one of the most widely spoken dialects among the ethnic Chinese in Malaya. Miao Xiu’s family, for instance, was from Guangdong (Canton) and so he was almost certainly conversant in Cantonese.

Another reason might be that Cantonese is more readily transmutable into writing as it has its own unique script corresponding to its sounds, used alongside standard characters. Hokkien, in contrast, is relatively less amenable to written representation as a good proportion of its lexis has no graphic representation. Cantonese words often appear in sprinklings, although it was not uncommon for entire stretches of dialogue to be couched in Cantonese, particularly when the characters are from the working class (in contrast, characters who are intellectuals generally did not converse in dialect). In addition to Cantonese, Hokkien and colloquial Malay also come up occasionally, albeit in smaller doses, hence contributing to the rich linguistic texture of the literary prose.

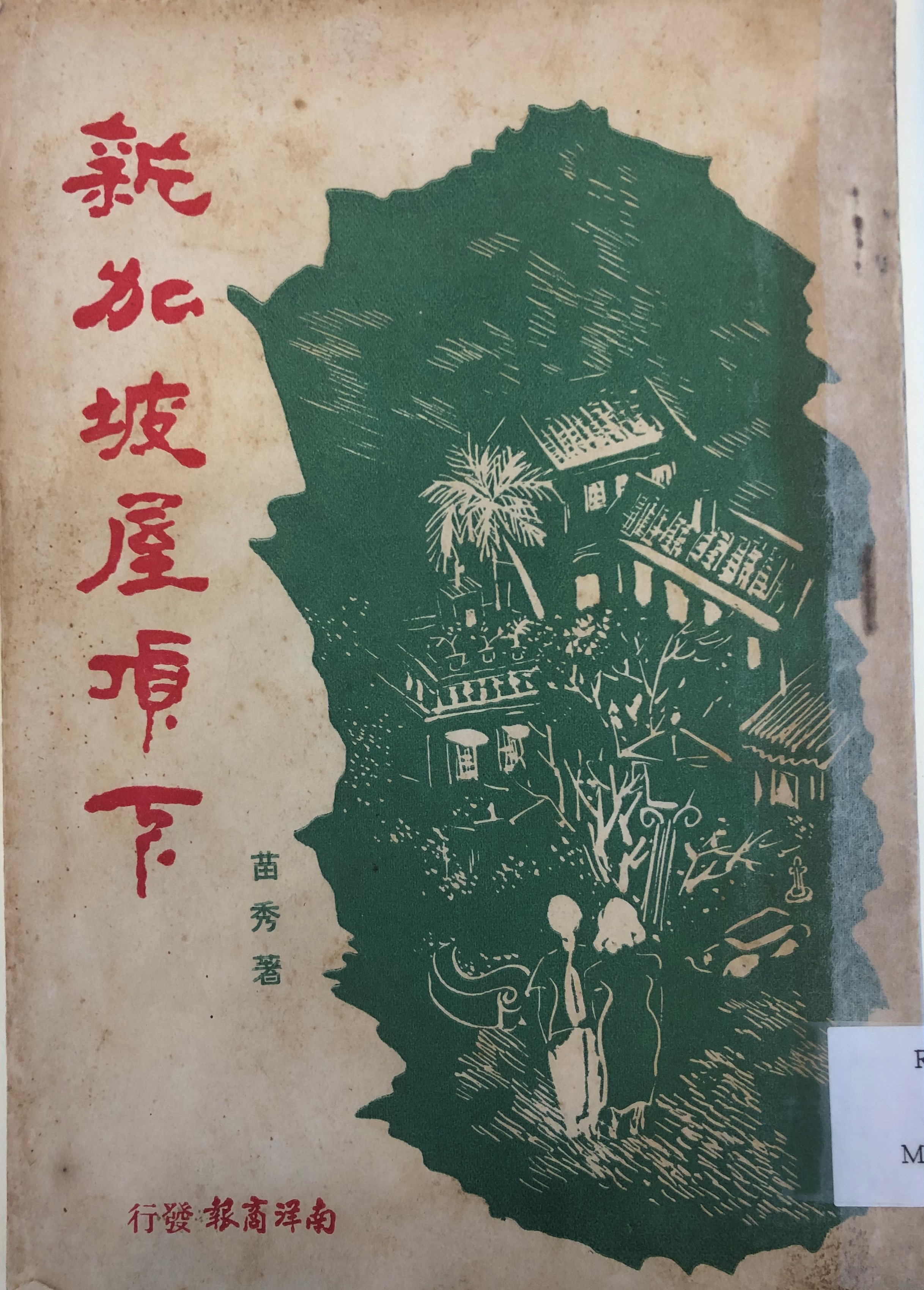

To take an example from Miao Xiu’s well-known novella Under Singapore’s Roof (1951), consider the following sentence:

這鬼是「七0七」的「草鞋」(私會黨的總務),每逢禮拜晚就來黑巷向她賽賽討「包爺費」,為了免得別的私會黨的三星臭卡「卡周」(馬來語:欺凌),她賽賽不她賽賽不得不忍痛付給這鬼一筆保護費;可是這臭卡一開口就是一巴掌(五扣錢),講到口乾才減到三扣。17

Here we see a succession of terms (in bold) that would surely baffle the non-local Chinese reader and, for that matter, even a contemporary Chinese reader with no access to Singapore’s sociocultural context in the 1940s and 1950s. These include the name of a triad society (七0七, or “707”), the informal term for someone who runs errands for triad societies (草鞋, literally, “straw sandal”), the slang for “protection money” (包爺費, literally, “fee for reserving the master”), the Hokkien term for runner (臭卡, literally “smelly leg”); the Malay term for “bully”(卡周 or kacau), the colloquial word for “five dollars” (一巴掌, literally “one slap”), and the term 扣 in Hokkien/Teochew for counting cash.

On occasion, Cantonese and Hokkien are mingled within a single utterance, increasing its heterogeneity. In some scenes characters interact using different dialects in alternation, for example, when one person speaks in Cantonese and the interlocutor responds in Hokkien. This technique of code-switching creates a complex weave of different voices on the page, even though it also produces a contrived linguistic style peculiar to the literary prose of this period.

English words figure sparingly in Chinese-transliterated form; and as with Chinese dialects and colloquial Malay, they are always marked by scare quotes to signal that the Chinese characters representing the English sounds are not to be read literally. To cite an example from Zhao Rong’s novella In Love with the Sea, the narrator says early in the story 尤其惹他厭惡的是那些旅客們,都穿上厚厚的「遮結」和絨衫 (“he particularly dislikes those tourists who put on thick jackets and velvet tops”). The two characters 遮結 do not form a Chinese word but rather translates the syllabic sounds of the word jacket. Note that there is also a Cantonese inflection here: the two characters need to be pronounced in Cantonese to derive a sound akin to jacket; reading them in Mandarin, for instance, would produce an incomprehensible word.

Annotations are often provided for terms transliterated from Chinese dialects or colloquial Malay. This suggests that fiction writers like Miao Xiu were not taking for granted that their readers would understand the non-Mandarin terms without assistance. For although Chinese dialects and colloquial Malay must have been readily heard on the streets during the 1950s, their representation in writing was a marked practice.

There is evidence to indicate that some readers of the day might have been alienated by the generous sprinkling of Chinese dialects words, in particular Cantonese. In a forum article published in Nanyang Siang Pau on 7 July 1954, one reader expressed frustration with a story written “entirely in Cantonese” published in the paper. The reader complained that Hokkien speakers like himself struggle to understand the plot and maintained that literary authors should write in standard Chinese.18 Hence, while the use of dialects (and colloquial Malay) in Chinese writing instantiated the “uniqueness of Malayan Chinese literature”, it was ultimately still experimental in nature.

“Champurisation”: EngMalChin and Malayan English Poetry

Chinese writers were not alone in experimenting with the linguistic medium of the literary arts. A similar development was taking place in Malaya during the same period among local writers and intellectuals working in English. Amid the rise of Malayan consciousness, a group of young students at the University of Malaya came up with the idea of amalgamating the various languages spoken in the region to create a synthetic medium for English-language poetry. Most prominent among these young advocates was Wang Gungwu (1930−), who would later become one of the most influential historians of Chinese diaspora. Pulse, a volume of Wang’s poems published in 1950, is today widely considered the first collection of English poetry by a Malayan writer.

The initiative championed by Wang and other kindred spirits was dubbed EngMalChin. It was an ambitious attempt to establish a new literary register based on English but specifically Malayan in constitution. A portmanteau conflating the first syllable of the words English, Malay and Chinese, EngMalChin “alludes to the way in which the English of a poem made room for Malay and Chinese words and phrases”.19 Paradigmatic of this linguistic style is Wang’s 1950 poem “Ahmad”, in particular its last two stanzas featuring codeswitching into Malay:

His wife with child again.

Three times had he fasted,

And puasa was coming round once more.

One hundred to start with – a good scheme;

Quarters too,

With a room for his two little girls.

Kampong Batu was dirty!

Thoughts of Camford fading,

Contentment creeping in.

Allah has been kind;

Orang puteh has been kind.

Only yesterday his brother said,

“Can get lagi satu wife lah!”20

As far as the notion of English poetry is concerned, the presence of Malay – puasa (Muslim fasting period), kampong (village), Allah (God in Islam), orang puteh (white men) and “Can get lagi satu wife lah!” (Can get another wife!) – would have been highly unusual for Wang’s readers at the time. Another example of Wang’s writing that highlights EngMalChin is “Three Faces of Night”, which explores different facets of life in Malayan Singapore. One of these is the familiar scene of roadside hawkers:

The crowds wait their share of the steaming fun

At the kuey teow stalls of the kerosene glare

And in the shadowed, rubbish lined malls,

The whisperings have just begun.

By the drains, sandalled squats

Lick their durian seeds;

Near the lanes the night-soil workers

Wipe their stinking beads;

And urchins at the car park do their good deeds.

The herbal cool-tea colours the bowls;

Mango skins attract the flies.

Oh watch the chee-kee woman cense the skies,

Crying,

“This is our progressive Paradise.”21

Apart from obvious evidence of codemixing like kuey teow (Chinese rice noodles), the poem experiments with the intersections of English and Chinese. “Fun” in “their share of the steaming fun” cleverly puns the English word for delight and the sound of the Cantonese word for “rice noodles”. Similarly, “chee-kee” in “watch the chee-kee woman” gives rise to two readings: while calling up the word “cheeky”, it transliterates a Chinese dialect term possibly referencing the incense sticks used in Chinese folk rituals. These double-entendres capture the palimpsestic sensibilities in colonial Malaya at a time when the lingering British influence and emergent local consciousness interfaced as co-existing social forces-in-tension.

Wang also has a penchant for coming up with his own hyphenated compounds in English, as in “cool-tea”, calqued from the Chinese words for “herbal tea”. Uncanny terms such as these give English words a Malayan inflection, “highlight[ing] a simultaneous normalisation of Chinese dialects in daily parlance, but also a sense of linguistic estrangement”.22 In modern sociolinguistic parlance, such new morphologies would be described as a translanguaging practice, where translanguaging refers to the creative and critical use of diverse resources (both linguistic and non-linguistic) in multilingual communication, pointing to a creative hybridization of identities.23

Therein lies the motivation for EngMalChin, specifically designed to invoke “plural imaginings of Malaya”,24 to promote a multivocality that simultaneously dwells within and pushes against the colonial imaginary. From a purely literary standpoint the results are mixed; while the mixing of vernaculars gives rise to a grassroots aesthetic, there is a certain dissonance in EngMalChin formulations that render them a tad contrived. What is pertinent, however, is the language ideological thrust of the campaign. As Philip Holden comments with regard to Wang’s experiments in Pulse,

“If some of the phrasing at times seems awkward, and the references obscure, we should remember that Pulse is one of the first efforts to produce a distinctively Malayan voice in English-language poetry. As such, the poems collected in the volume attempts to wrest English-language poetry from ‘the implicit body of assumptions to which [it] was attached, its aesthetic and social values, the formal and historically limited constraints of genre’ [Ashcroft et. al. 10-11] and put it to use in a new context.”25

Whereas the mixing of languages, as demonstrated in “Ahmad” and “Three Faces of Night” would be most unextraordinary today, in the postwar decade, it was a refreshing and radical idea. In a 1958 essay reflecting the spirit of EngMalChin, Wang reminisced that he and other student poets were “self-consciously Malayan” and were invested in the distinctiveness of English as it was used in Malaya: “What floored us was the illegitimate mixing of various languages; our stock example of this was ‘Itu stamp ta’ ada gum ta’ boleh stick-lah’ [meaning ‘the stamp has no glue so it can’t stick’]. What can we make of that? We could not even decide whether that was Malay with a few English words or English with a Malay syntax”.26

EngMalChin therefore thrived on an ambivalence that came from the fusion of different tongues. It branded itself as a linguistic signature that distinguished Malayan English from British English. In a 1950 article published in the journal Young Malayans, Beda Lim, a contemporary of Wang’s, described Malayan English as a “champurised language” – “champurised” taking reference from the Malay word champur, meaning “to mix”, creatively inflected into a past perfect form as if it were an English word. In making a case for Malayan English as a “solution for Malaya”, Lim strongly advocates for the idea of a register of English attuned to local “speech rhythms”. Lim’s argument, iconoclastic in 1950s Malaya, is worth quoting at length:

“What can be done in Malaya is an ironing out of the different speech rhythms into a standard speech. The conditions of living under which we have lived from generation to generation are quite different from those in England. Our speech rhythms must therefore be different… Although we use English words, the way we juxtapose them must necessarily be different from the way the English people do it. These are facts that we have to face squarely… Champurisation should not be frowned upon but rather should be regarded as a healthy development. Some local words will stick and others will fall off. Time will decide… The creative writer must live in a climate of spoken language, and as long as the climate is not formulated his medium will be one that is purely experimental and will eventually die out. When the standard Malayan speech has been fixed to some degree it will be possible for creative writing in Malaya to get out of its experimental stage and get down to business.”27

The term EngMalChin does not appear in Lim’s article, but the word champur in its various forms (“champurised”, “champurisation”) itself already embodies the multilingual ethos of EngMalChin. The term is, therefore, metalinguistic in this usage: it is an EngMalChin word about the nature of EngMalChin. And while EngMalChin manifests primarily in poetry, it was not purely or even primarily a literary or aesthetic project; its sociopolitical agenda was clear from the outset. As Wang recalled: “We persisted, however, not so much for the art of poetry as for the ideal of the new Malayan consciousness. The emphasis in our search for ‘Malayan poetry’ was in the word, ‘Malayan’”.28

Lim, while championing the cause of a Malayan brand of English, inadvertently foreshadowed EngMalChin’s destiny: the movement did eventually die out, as Lim had portended. Before the close of the decade, it was already clear that EngMalChin had become a floundered mission. There was no “get[ting] down to business”, as Lim would have hoped for. In his 1958 essay Wang conceded that there was an inherent paradox of seeking a Malayan identity through an English-language matrix: “the most serious error was… the contradiction between our search for Malayan poetry and our decision to base that search on the English verse forms”.29

The assumption here is that Malayan and English are incongruous, even oppositional in a colonial context. Yet language and identity are not coterminous. The apparent contradiction identified by Wang is inherent in other discursive instantiations of locale-based identity. Attesting to this are well-known examples of postcolonial literature in English – think Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe (1930–2013) and Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (1938–), for instance – and the vibrant varieties of World Englishes (in the plural) spawned throughout the former Anglo-American colonies and beyond, say, Nigerian English, Caribbean English, and so forth. In this vein, one might argue against Wang to the effect that there is no necessary tension in searching for a Malayan identity through English-language writing.

To my mind, the visions of EngMalChin were a little too idealistic to start with. It endeavoured to cross the registers of speech and writing, as Beda Lim envisioned, “[t]he creative writer must live in a climate of spoken language. . . When the standard Malayan speech has been fixed to some degree it will be possible for creative writing in Malaya to get out of its experimental stage and get down to business”.30 But the young minds behind The New Cauldron, a literary magazine in the 1950s edited by students, including Wang, from the University of Malaya, were classically trained in English literature. This is evidenced by many of the poems published by Wang and his contemporaries, which were reminiscent of the work of canonical writers à la T.S. Eliot.

The New Cauldron

was a literary journal edited by students at the University of Malaya. Published by Raffles Society, University of Malaya, 1952. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 052 NC)

The New Cauldron

was a literary journal edited by students at the University of Malaya. Published by Raffles Society, University of Malaya, 1952. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 052 NC)

For these persons to embrace the practice of code-mixing in poetry would have been tantamount to subverting the monumental tradition that undergirded their English-language education, a move that would hardly be easy to execute at a time when Malaya was still couching beneath the shadow of imperialism.

The crucial reason for EngMalChin’s failure, however, was its lack of exemplification. In contrast to the practice of using dialects in Chinese-language fiction discussed earlier, EngMalChin was very much a theoretical enterprise without a substantial empirical basis.31 There were just too few authors actually experimenting with EngMalChin to render it meaningful, much less sustain it for a sufficient period to make an impact on literature and society.

The primary ground where EngMalChin was practised was The New Cauldron. But a survey of all the issues of the magazine published in the decade shows scant evidence of EngMalChin. Save for a small handful of Wang’s poems like “Ahmad”, the works published in The New Cauldron were hardly experimental in the sense envisioned by Lim. In other words, what Lim called champurisation very much subsisted on the level of discourse, and relatively briefly. Because it never really took off in practice, EngMalChin remained very much an aspirational notion.

Rearticulating Identity: The Sinophone and Anglophone as Expressions of Linguistic Citizenship

It is no coincidence that the Chinese-language and English-language writers in Malaya experimented with the medium of expression in their respective literary spheres within the same period, engendering the possibility of a distinctive multilingual voice, or multivocality, for Malayan writing. This is especially so because, as Han Suyin observed, there was little communication between the two communities.32 It was the effervescent ambience of Malayan society in the 1950s that encouraged linguistic experimentations with a view to fostering a distinct sense of locality in writing.

In effect, Chinese-language and English-language writing were pivoting toward what may be called Sinophone and Anglophone writing. The latter two descriptive labels bear a different connotation than their conventional dictionary-level meanings. In comparative literary theory, the term Sinophone is not co-extensive with “Chinese-speaking” or “written in Chinese”. Rather, it gestures toward a Chineseness-beyond-China with a view to

“disrupt[ing] the chain of equivalence established, since the rise of nation-states, among language, culture, ethnicity, and nationality and [explores] the protean, kaleidoscopic, creative, and overlapping margins of China and Chineseness, America and Americanness, Malaysia and Malaysianness, Taiwan and Taiwanness, and so on, by a consideration of specific, local Sinophone texts, cultures, and practices produced in and from these margins.”33

Hence, to invoke the Sinophone (with a capital S) is to say something more than speaking or writing in Chinese (with mainland China as the point of reference), which might be described as the sinophone (with a lowercase s). It is to signal a peripheral as well as politicised perspective on the act of enunciating Chinese, not necessarily – indeed, very often not – in its standardised forms. In the same vein, the Anglophone might be posited as an identity construct exceeding the usual sense of “English-speaking” or “written in English” (the “anglophone”, with Britain as the point of reference) to encompasses myriad Englishes. Applying this to the case at hand, the Malayan writers and intellectuals of the 1950s rearticulated – the phonetic connection here is significant – Chinese and English into locally-inflected voices. These voices, namely the Sinophone and the Anglophone, were decidedly heterogeneous, with local writers breaking with their respective literary sources to invent an “adulterated” discourse constituted by the plethora of tongues in Malaya.

To use dialects in Chinese-language fiction, otherwise written in the standard vernacular, is to perform marginal identities by way of the Sinophone. Similarly, to propose a new method of writing English poetry comprising a cocktail of English, Malay, and Chinese is to espouse an alternative poetics around the Anglophone refracted through the lens of Malaya.

It is through this thrown-togetherness of tongues that writers in the 1950s jointly articulated an imagined utopia in Malaya. Multivocal writing, as it were, is not simply about language and literature; it is the symptom of a burgeoning linguistic citizenship. Linguistic citizenship refers to a condition where “representing languages in particular ways becomes crucial to, becomes the very dynamic through which, acts of agency and participation, and reconceptualizations of self in matrices of power occur”.34

It is a richly political concept designed to capture the idea that language falls firmly within citizenship discourses, and that it is, in fact, the very medium whereby politics is enacted and performed. . . an important dimension of the political is the potential for political action to bring about alternative worlds, what [Ben Anderson] has referred to as the “utopian surplus” in the notion of citizenship.35

Where national identity is under contention, as it was in 1950s Malaya, language conjoins with citizenship as “an acknowledgement of the deeply entangled dependencies between language and politics”; here, language may be subjected to alternative construal to “open up for new political scenographies”, with a view to advocating for “a more encompassing and inclusive forms of citizenship agency and participation”.36 This insight on the intersection of language and citizenship allows us to understand how, as a modality of expression, literary composition is tied to the fervent sociopolitics of 1950s Malaya.

In other words, the experimental impulse of Malayan writers toward multivocal writing did not come out of the blue. Rather, such an impulse speaks to negotiations of identity in the midst and immediate aftermath of Malaya’s geopolitical transition from colonialism to nationalism. Through their experimentation with plural voices, writers in both Chinese and English endeavoured to “capture the utopic experience of thinking language otherwise”,37 hence articulating Sinophone and Anglophone (in uppercase) sensibilities out of sinophone and anglophone (in lowercase) literary traditions respectively.

In other words, multilingualism embodies a utopian vision. Writers, on this view, were not ivory-tower purveyors of literary aesthetics, but engaged agents of sociopolitical change; and, as a corollary, language is as much (if not more) a vehicle for identity work as it is a tool for composition. In signalling resistance against a monolithic imagining of Malaya, literary multivocality underscored codemixing, which connoted heterogeneous identity formations in the wake of postcolonialism. Linguistic citizenship as consummated in experimental writing thus precedes and lays the conceptual grounds for the making of a geopolitical citizenship for Malaya, which was realised toward the end of the 1950s.

Lee Tong King is a Professor of Language and Communication in the School of English, University of Hong Kong. He was a National Library Singapore Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow in 2022–23.

Lee Tong King is a Professor of Language and Communication in the School of English, University of Hong Kong. He was a National Library Singapore Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow in 2022–23. NOTES

-

Liviniyah P., “Malayan Emergency”, Singapore Infopedia, published May 2019. ↩

-

Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1991). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 320.54 AND) ↩

-

Sean Khok Chua@Xie Ke, oral history interview by Lye Soo Choon, 20 May 2003, transcript and MP3 audio, 00:29:35, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 002761), reel 1, disc 71. ↩

-

Han Suyin, “An Outline of Malayan-Chinese Literature”, Eastern Horizon 3, no. 6 (June 1964): 10. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. 950.05 EHMR) ↩

-

Tang Eng Teik, “Uniqueness of Malayan Chinese Literature: Literary Polemic in the Forties”, Asian Culture 12 (December 1988): 102–15. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING q950.05 AC) ↩

-

Wang Gungwu, “A Short Introduction to Chinese Writing in Malaya,” in Bunga Emas: An Anthology of Contemporary Malaysian Literature (1930__–1963), ed. T. Wignesan (Malaysia: Rayirath Publications, 1964), 251. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 828.99595 BUN) ↩

-

Low Choo Chin, “The Repatriation of the Chinese as a Counter-Insurgency Policy During the Malayan Emergency”, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 45, no. 3 (October 2014): 363−392. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.005 JSA) ↩

-

Regulations Made Under the Emergency Regulations, 1948 (F. of M. Ord. No. 10 of 1948) incorporating all amendments made up to the 31st March, 1953 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 348.595 MAL) ↩

-

Jeremy E. Taylor, “‘Not a Particularly Happy Expression’: ‘Malayanization’ and the China Threat in Britain’s Late-Colonial Southeast Asian Territories,” Journal of Asian Studies 78, no. 4 (November 2019): 792. (National Library, Singapore, call no. 950.05 FEQ) ↩

-

Wang, “A Short Introduction to Chinese Writing in Malaya,” 252. ↩

-

Tan Chee Lay, “Chinese Literature: From Nanyang to Multiculturalism,” in Literature, ed. Koh T. A., Singapore Chronicles series (Singapore: Institute of Policy Studies, NUS, and Straits Times Press, 2018), 46. ↩

-

Wen Renjun (Miao Xiu), “On Overseas Chinese Consciousness and the Uniqueness of Malayan Chinese,” Sin Chew Jit Poh, 28 February 1948. (From National Library, Singapore Microfilm, reel no. A01597329C) ↩

-

Xi Qiao (Zhao Rong), “A Concise Discussion of Immigrant Literature and Art,” Sin Chew Jit Poh (Xing Chen supplement), 26 January 1948. (National Library, Singapore Microfilm, reel no. A01597329C). ↩

-

Xi Qiao (Zhao Rong), “A Resolution of the Problem,” Sin Chew Jit Poh (Xing Chen supplement), 16 February 1948. (National Library, Singapore Microfilm, reel no. A01597329C). ↩

-

Zhao Rong, 古老石山 (Old Stone Mountain), 芭洋上 (On the Sea of Villages), (Singapore: Qingnian shuju, 1958), 43–52. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Chinese 813.4 ZR) ↩

-

Emphasis added. Miao Xiu, Xinjiapo wuding xia 新加坡屋頂下 [Under Singapore’s roof] (Singapore: Nanyang Printing Press, 1951,) 6. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Chinese C813.4 MX) ↩

-

_ Li Wen 李文_,_ “Guanyu fangyan wenxue,” 關於方言文學 [About dialect literature], 南洋商报 Nanyang Siang Pau, 7 July 1954, 8. (From NewspaperSG). This point was mentioned by former Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow Seah Cheng Ta in his online presentation “Singapore Chinese Literature and Literary Supplements in the 1950s,” 26 March 2021, video, 26:27, (From NLB Singapore YouTube channel). ↩

-

Rajeev S. Patke and Philip Holden, The Routledge Concise History of Southeast Asian Writing in English (London: Routledge, 2010), 51 (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 895.9 PAT) ↩

-

Wang Gungwu, “Ahmad,” Pulau Ujong, accessed 27 October 2023, https://www.pulauujong.org/8-2/ahmad/. Originally published in Wang Gungwu, Pulse (Singapore: B. Lim, 1950). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 828.99595 WAN) ↩

-

Wang Gungwu, “Three Faces of Night,” Pulau Ujong, accessed 27 October 2023, https://www.pulauujong.org/8-2/three-faces-of-night/. ↩

-

Jonathan Chan, “Critical Introduction”, poetry.sg, published 11 June 2021, http://www.poetry.sg/wang-gungwu-intro. ↩

-

Li Wei, “Translanguaging as a Practical Theory of Language”, Applied Linguistics 39 (2018): 9–30. ↩

-

Brandon Liew, “Engmalchin and the Plural Imaginings of Malaysia; Or, the ‘Arty-Crafty Dodgers of Reality’,” Exclamat!on: An Interdisciplinary Journal, issue 2 (2018): 65. ↩

-

Philip Holden, Introduction to “Wang Gungwu, Pulse,” accessed 6 May 2024, https://www.pulauujong.org/8-2/. ↩

-

Wang Gungwu, “Trial and Error in Malayan Poetry,” Malayan Undergrad 9, no. 5 (1958): 6. (From PublicationSG) ↩

-

Beda Lim, “Malayan English: A ‘Champurised’ Language!” Young Malayans 6, no. 91 (5 July 1950): 202. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RDTYK 079.595 YM) ↩

-

Wang, “Trial and Error”, 6. ↩

-

Wang, “Trial and Error”, 6. ↩

-

Beda Lim, “Malayan English”, 202. ↩

-

The author is grateful to Philip Holden for raising this point. ↩

-

Han, “Outline of Malayan-Chinese Literature”, 16. ↩

-

Shih Shu-mei,“The Concept of the Sinophone,” PMLA 126, no. 3 (2011): 710–11. ↩

-

Christopher Stroud and Quentin Williams, “Multilingualism as Utopia: Fashioning Non-Racial Selves,” AILA Review, issue 30 (2017): 185. ↩

-

Christopher Stroud, “Linguistic Citizenship as Utopia,” Multilingual Margins 2, no. 2 (2015): 23. ↩

-

Stroud, “Linguistic Citizenship as Utopia,” 24. ↩

-

Stroud and Williams, “Multilingualism as Utopia,” 186. ↩