A Bridge Between East and West

Liu Kang’s works show the influence of Western artists such as Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh and Matisse, as well as the tradition of Chinese ink painting.

By Low Sze Wee

In November 1953, four artist-friends – Liu Kang, Chen Wen Hsi, Chen Chong Swee and Cheong Soo Pieng – held a joint exhibition showcasing more than 100 paintings and sketches inspired by their trip to Java and Bali a year earlier. It was the first time in Singapore that a group of local artists had organised a thematic exhibition based on their painting trip. The exhibition at the British Council was very well received and continues to be regarded as a milestone in Singapore’s art history today.1

Among the four artists who participated in the Bali exhibition, Liu Kang was the only one who painted primarily in oil, whereas the other three moved freely between Western oil and Chinese ink paintings. In fact, when the well-known visiting Chinese artist Xu Beihong (徐悲鸿) saw Liu’s oil painting at a group exhibition in Singapore in 1940, he exclaimed, “你才是马諦斯的老师” (“You are truly the teacher of Matisse”).2

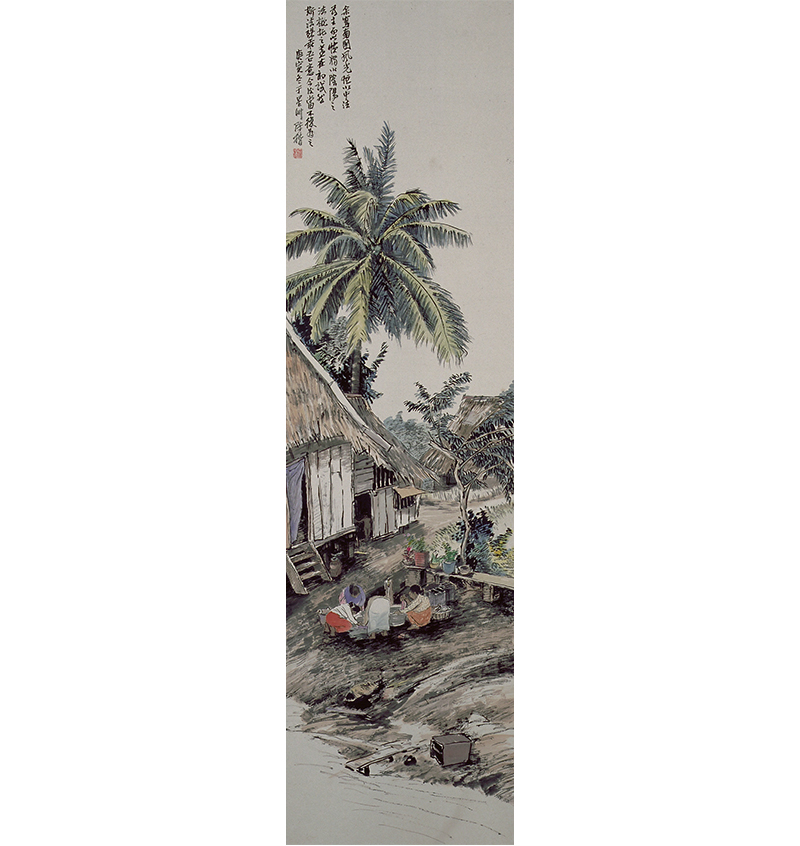

The work in question depicted a Malay village scene with attap houses surrounded by banana and coconut trees, and with the local folk and their chickens and ducks in the foreground. Although Xu did not explain what he meant, Liu speculated that his painting likely stood out because most of the other artists’ works were more “naturalistic” (“画得比较写实”). Liu’s style, on the other hand, was simpler, using flat colours and linework, rather than light and shade, to depict his subjects (“很爽朗、简洁,注重线条,不注重光线,色彩比较平浮的”).3

The comparison of Liu with the famous French artist Henri Matisse was not unexpected. After all, oil painting is an art medium that was introduced to Asia from the West. In addition, Liu had spent time in Paris in the 1930s and was a great admirer of Matisse’s works.4 However, it is important to note that Liu’s practice was not derivative of Western norms; he was not merely copying Matisse. Rather, Liu’s chosen medium and style arose because he saw close affinities between Western modern art and Chinese ink aesthetics. This was something that he often reiterated in his writings and artworks.

Liu Kang’s Artistic Journey

Born in 1911 in Fujian, China, Liu spent his childhood years in the town of Muar in Johor. In 1926, at the age of 15, he returned to China to further his studies. A year later, he enrolled in the Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts (also known as Shanghai Art Academy), which later broke off to form Xinhua Academy of Fine Arts (or Xinhua Art Academy) and graduated from the latter in 1928.

Between 1928 and 1933, he continued his studies at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris where he had the chance to exhibit at the annual Salon d’Automne.5 His works from that period bear strong influences from the French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists.

In 1933, Liu returned to China and taught Western painting at the Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts until the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937, which led him and his wife to move to Singapore and later Muar. After the end of the Second World War, he settled down in Singapore where he ran a studio producing advertisements and cinema posters. Apart from teaching art in various schools, he was very active in the local art community, serving in various societies and committees. Liu’s works have been shown internationally in places such as Taiwan, Hong Kong and Beijing.

In 2003, Liu donated his life’s works to the Singapore Art Museum. For his contributions to the Singapore art scene as artist, teacher and writer, Liu received the Bintang Bakti Masyarakat (Public Service Star) and Pingat Jasa Gemilang (Meritorious Service Medal) in 1970 and 1996 respectively. He died in 2004.

Inspiration from the West

Liu’s interest and engagement with the West was an enduring one, spanning his years in Shanghai to his time in Paris and, later, Singapore. His lifelong interest in Western art probably started when his primary school teacher in Muar, recognising his love for art, gave him a book of reproductions of Western art. Liu spent many happy hours copying artworks from the book.6

When Liu returned to China to further his studies, the country had become a modern republic with the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1911. In the wake of China’s humiliating defeat to a technologically superior West, many artists regarded Chinese painting, with its traditional emphasis on copying from old masters, as fossilised and irrelevant to a new China. There was intense debate over the creation of art for a new nation and era, and the role that the West could play in the process.

By the 1920s, Shanghai had become the art centre of China. Apart from Chinese painting, art schools like the Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts and the Xinhua Academy of Fine Arts also taught Western oil painting since a number of their teachers had studied Western art in Paris or Japan.7

After graduating from the Xinhua Academy of Fine Arts in 1928, Liu left for Paris to continue his art studies until 1933. Being at the heart of the Western art world then, Liu had the opportunity to study paintings previously known only from reproductions. He recalled: “After seeing an exhibition of Cézanne still-life paintings, the next morning we would be arranging a still-life ‘a-la Cézanne’ and painted it in his style, using his colour scheme. We tried to enter his state of mind when he was painting the subject.”8 Liu also visited many art museums to study Western masterpieces, and went on painting trips to Italy, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark and the United Kingdom.9

Admiration for Matisse

Liu readily acknowledged his influence by modern Western artists.10 “Art was a subject I did well in school,” he said. “I started on pencil drawings and was weaned on Western art. In my paintings, you can detect my debt to Van Gogh, Matisse and Gauguin; I was an earnest student of their styles. They are vigorously descriptive, with a strong sense of space and perspective.”11

Works from Liu’s Paris period in the early 1930s – such as Autumn Colours (1930), Farmer’s House (1930) and Breakfast (1932) – reflect the influence of the abovementioned artists in terms of the “expressiveness of brush strokes, imposing presence of forms, and flattening and merging of planes to construct colour blocks”.12 Among the Western artists, Liu admired Matisse greatly.13 He regarded the latter, along with Picasso, as the two key artists of 20th-century Western art.14 Liu said of Matisse: “My artistic career has been very much influenced by this leader of the Fauvist school. Matisse influenced me in many ways – the pursuit of innovation, the expansion of bold vision and the sublimation of images.”15

Liu was impressed by Matisse’s paintings with their brilliant colour, fluid lines and emotional exuberance. Shading, modelling and perspective are secondary to colour, which is used to create mood and emotion.16 Although Matisse’s works are never fully non-representational, they often evoke the abstraction found in music, where a sense of rhythm and harmony is conveyed through the play of lines and colours.

Matisse once wrote: “Expression, for me, does not reside in passions glowing in a human face or manifested by violent movement. The entire arrangement of my picture is expressive; the place occupied by the figures, the empty spaces around them, the proportions, everything has its share [emphasis added].”17 He further wrote: “I cannot copy nature in a servile way; I am forced to interpret nature and submit it to the spirit of the picture. From the relationship I have found in all the tones, there must result a living harmony of colours, a harmony analogous to that of a musical composition [emphasis added].”18

Affinities with Chinese Ink Aesthetics

Matisse’s emphasis on negative and positive space, and his desire to go beyond representation are tenets shared by Chinese ink painting aesthetics. In traditional Chinese painting, portions of the paper are left unpainted to suggest the sky, water or ground, depending on the context. A harmonious balance is sought between the painted and unpainted parts.

Likewise, in the “写意” (xieyi; writing the idea) style of painting favoured by the literati artists, the expressive qualities of painting were preferred over purely objective depictions. The traditional scholar-artist was not concerned with physical likeness, but focused on capturing the spirit or essence of the subject, which in turn was seen as a reflection of the artist’s temperament and character.

Hence, Matisse’s modernist approach, with its emphases on subjectivity rather than representation, was consistent with literati “写意” (xieyi) principles.19 In this respect, Liu saw affinity between Matisse’s practice and his own Chinese cultural heritage. He said: “From an Easterner’s point of view, what Matisse did was not new because we have never stressed chiaroscuro and perspective. We have always counted on lines for depiction, and have never been that concerned with realism of the image.”20 Liu even went so far as to regard Cézanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin and Matisse as “Chinese artists” in Western art history.21

Straddling East and West

Liu was able to draw such insights because he belonged to a special generation of Chinese artists who were exposed to both Chinese and Western art traditions. In the early 20th century, China was just opening up to the possibilities of the West. Many intellectuals like the political reformer Kang Youwei (康有为) argued that China’s progress needed to be propelled by Western science and technology.

The May Fourth Movement in 1919 further ignited the drive to strengthen China through cultural reforms, resulting in traditional Confucian concepts giving way to Western ideas. Consequently, China’s education system sought to integrate Western knowledge as a way of modernising the country. Art education was no exception.

In the past, Chinese painting was traditionally taught by making students copy the works of senior artists and masterpieces. Increasing contact with the West and Japan in the early 20th century led to the emergence of art schools in China that favoured Western-style – or, at least, what was then perceived to be more scientific – methods of instruction. Hence, the first Chinese government art schools to teach Western art emphasised draughtsmanship, focusing on perspective, light and shade as well as accuracy of depiction.22

Common teaching methods included using pencil, charcoal, watercolour and oils for drawing from plaster casts, still-life and nude studies, and painting from nature.23 Concurrently, these art academies continued to teach Chinese ink painting. However, Western art, with its structured methodology of instruction, was easier to teach. Hence, the academies tended to start with Western art as a foundation course. Chinese art was deemed more conceptual and therefore usually offered at the advanced level. This marked a new generation of artists who were more distanced from Chinese art. However, they were also the first who were at least familiar with, if not proficient in, both Western and Chinese art traditions.24

With such a bicultural foundation, Liu often sought to imbue a sense of Chinese identity in his Western oil paintings.25 He said: “I am an Oriental… When I pick up a brush, the forms and artistry which flow out from my hand are discernibly different from a Westerner.”26 On another occasion, he said: “I have tried to reveal the robust spirit, profound content and refined taste of her [China’s] culture in my paintings.”27 This was also something that Liu’s mentor, Liu Haisu (刘海粟), constantly urged his students to do, which was to “paint Western art through Chinese eyes and feelings”.28

Liu sought to achieve this on two levels. First, he avoided reworking his canvases as much as possible to retain an air of spontaneity, a quality much admired in “写意” (xieyi) painting. Liu’s son, Liu Thai Ker, an architect and former master planner of the Urban Redevelopment Authority of Singapore, said of his father’s method of painting: “He could spend many more days staring at the canvas, just constructing the entire painting in his mind, including the use of colours and the application of brushstrokes. The actual execution of the painting normally takes up a relatively short time and involves little working over. The discipline is not unlike that of a Chinese painter, in the sense that once a line or a patch of colour is put down on the paper, it is final and beyond correction. Thus, spontaneity is preserved, the freshness and boldness captured.”29

Liu also paid increasing attention to the use of lines in his paintings. Upon his return to China from Paris in 1933, Liu started studying Chinese painting and calligraphy with a new intensity. “[He] combined Chinese brush technique with an Impressionist palette to convey the ephemeral effect of light on his landscapes… There was a tentative effort at delineating objects with dark lines which, at a later stage, was to become a dominant feature in his work.”30

As observed by art historian Kwok Kian Chow, when comparing three of Liu’s works, a gradual thickening of outlines in defining object and spaces could be discerned, “suggesting an affiliation with the linear brush quality of Chinese ink painting”.31 Kwok further noted: “In the 1940s, Liu was infusing his oil paintings with Chinese ink brushwork and particularly the abbreviated and caricature-like descriptive brushwork of folk genre paintings.”32 In Liu’s paintings such as Durian Vendor (1957), Sarongs (1969) and Life by the River (1975), there is an evident use of black or dark outlines to accentuate forms, and convey a sense of liveliness.

Liu’s peers also noted the influence of Chinese ink techniques on Liu’s works. Lee Siow Mong, president of the China Society, said: “Although he [Liu Kang] is a finished product in Western pictorial art, I can see that the outstanding quality of his works is the infallible technique of his brushwork which is the essence of Chinese pictorial art. His lines are delicately Chinese, and no doubt his Chinese scholarship has given him this advantage… The colourful Malayan scenes have given him courage to use colour, and I must say that I have always recognised Mr Liu’s works by the vigour of his colour.”33

Tradition and Modernity

Liu was not alone in his pursuit of marrying Western and Chinese art forms. He was part of a generation of artists who were actively seeking to create works that reflected their identities as modern artists in China in the early 20th century. However, due to various circumstances, a number of them, like Liu, left China and eventually settled down in Singapore between the 1930s and 1950s.

In their new home, these artists could continue their modernist pursuits without much interference, unlike in China where modern art was discouraged by the Chinese Communist Party which came to power in 1949. In the relatively more stable environment of Singapore, these Chinese migrant artists continued to work and hone their craft. Local schools provided them with employment as art teachers, while art societies gave them platforms for exhibitions and artistic exchange. Books and information on world art were also more readily available.

By the 1950s, the lively art scene and market in Singapore were supported by a growing network of collectors, exhibition venues, art societies, writers, curators and art supplies shops.34 The critical and commercial success of the 1953 Bali exhibition is a reflection of the many opportunities given to Liu and his peers to integrate their understanding of Western and Chinese art, and the appreciation of their artistic innovations in Singapore.

This led to considerable experimentations in both the ink and oil media. Artists like Chen Chong Swee incorporated Western fixed-point perspective and the use of shadows in their ink paintings – traits not usually found in traditional Chinese paintings. Others like Chen Wen Hsi adopted Western modern styles such as Cubism and Abstraction to create unconventional compositions for their ink paintings.

There were similarly innovative approaches in oil paintings. For instance, Cheong Soo Pieng favoured the prominent use of black lines and thin washes of colour to imbue his oil paintings with the atmospheric mood associated with “写意” (xieyi) landscapes. Others like Yeh Chi Wei incorporated archaic-style Chinese inscriptions in their oil paintings to convey the flavour of ancient ink rubbings. These artists demonstrated an openness to new ways of expression, and the ability to draw freely from diverse sources of art traditions and practices in their pursuit of modern art.

The study of modern Asian art is complex. Artists like Liu grappled with the forces of tradition and modernity as they sought to create works that expressed the society they lived in during an era of unprecedented changes and opportunities. Hence, it is problematic to categorise their works in Western-centric terms. It is neither helpful nor illuminating to regard Liu as a “teacher” or “follower” of Matisse. Rather, such artworks need to be understood within their own specific socio-historical contexts. This is especially critical in throwing light on how Asian societies (of which artists form a part) assert their identities in an ongoing dialogue with Western modernity.

Low Sze Wee is Group Director (Museums), National Heritage Board Singapore. He is the former Chief Executive Officer of the Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre.

Low Sze Wee is Group Director (Museums), National Heritage Board Singapore. He is the former Chief Executive Officer of the Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre.NOTES

-

“Bali – By 4 Chinese Artists,” Straits Times, 10 November 1953, 2. (From NewspaperSG ↩

-

In Liu Kang’s oral history interview, he mentioned this incident twice, using slightly different phrases. In one account, Xu was supposed to have said, “This painting is truly the teacher of Matisse” (“这张画才是马諦斯的老师”). See Liu Kang, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 7 December 1982, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 21 of 74, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000171), 186–194; 刘抗 Liu Kang, “四十五年来新加坡的西洋画,” (Development of Western painting in Singapore in the past 45 years) in Liu Kang: Essays on Art & Culture, ed. Sara Siew (Singapore: National Art Gallery, 2011), 232–33. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 709.50904 LIU); 刘抗 Liu Kang,刘抗文集 [Essays by Liu Kang] (新加坡: 教育出版社, 1981), 304. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 709.2 LK) ↩

-

Liu Kang, interview, 7 December 1982, Reel/Disc 21 of 74, 186–94. ↩

-

Born in 1869 in France, Henri-Émile-Benoît Matisse moved to Paris to study art in 1891. He experimented with many styles and went on to create brightly coloured paintings, applied with a variety of brushwork styles, ranging from thick impasto to flat areas of pure pigment. Such paintings, when exhibited at the 1905 Salon d’Automne, gave rise to the first of the avant-garde art movements, Fauvism (from the French fauves, or “wild beasts”), named by a contemporary art critic who derided its arbitrary combinations of brilliant colours and energetic brushwork. Subsequently, although Matisse’s styles changed over the years, his underlying aim was always, as he had put it, to discover “the essential character” of things and to produce an art of “balance, purity and serenity”. He died in 1954. See Henri Matisse, “Notes of a Painter,” 1908, https://www.arthistoryproject.com/artists/henri-matisse/notes-of-a-painter/; Jack D. Flam, ed. Matisse on Art (Oxford: Phaidon, 1978), 37. ↩

-

There is still some ambiguity over whether Liu Kang had instead attended École nationale supérieure des Beaux-arts since his brother-in-law Chen Jen Hao (with whom he travelled to Paris) was said to have studied at that art school. See Chen Jen Hao, Painting and Calligraphy (Singapore: Siaw-Tao Chinese Seal Carving Calligraphy and Painting Society, 2006). ↩

-

Chia Wai Hon, “Introduction,” in Liu Kang, Liu Kang at 87 (Singapore: National Arts Council and National Heritage Board, 1997), 10–11. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 759.95957 LIU) ↩

-

Both Japan and France were sources of Western-style art education for early Chinese artists. By the late 19th century, Japan was already a modern nation-state with an education system based on the Western model. By 1876, the government had set up the first official institution of art education that aimed to apply modern European techniques to traditional Japanese methods with instructors hired from Italy. Similarly, Liu Kang recalled that the teachers in Western painting at the Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts in the late 1920s were highly interested in Impressionism as many had studied in France. Teachers such as Chen Hong, Wu Dayu and Gao Leyi frequently mentioned the importance of the fleeting effects of light, warm and cool colour relationships as well as dynamic brushwork, and admired artists like Manet, Monet and Degas. See Liu Kang, “An Artist in Art Education,” in Chen Renhao 陈人浩, 人浩书画: The Collection of Chinese Calligraphy and Painting by the Late Mr Chen Jen Hao (新加坡: 新加坡中华书学协会, 1984), n.p. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 759.95957 CJH) ↩

-

Chia, “Introduction,” 16. ↩

-

Chia, “Introduction,” 15. ↩

-

This has also been noted by other commentators such as the artist Pan Shou and art promoter Frank Sullivan, who mentioned Liu Kang’s admiration of Cézanne, Gauguin, Utrillo, Dufy and, particularly, Van Gogh and Matisse. See Liu Kang 刘抗, 刘抗画集 [Collection of Liu Kang’s paintings] ([Singapore: n.p., 1957), x. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 759.95957 LK-[LK]) ↩

-

Richard Lim, ed., Singapore Artists Speak (Singapore: C.H. Yeo, 1990), 68. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 709.5957 SIN) ↩

-

Kwok Kian Chow, Channels and Confluences: A History of Singapore Art (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 1996), 52. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 709.5957 KWO) ↩

-

Liu wrote two articles on Matisse, one in 1951 (pp. 28–37) and the other in 1971 (pp. 122–132). See Liu, 刘抗文集, 28–37, 122–32. ↩

-

Liu, Liu Kang at 87, 30. ↩

-

Liu, Liu Kang at 87, 26. ↩

-

Matisse’s writings are illuminating in this aspect. He wrote: “The chief function of colour should be to serve expression as well as possible. I put down my tones without a preconceived plan. If at first, and perhaps without my having been conscious of it, one tone has particularly seduced or caught me, more often than not once the picture is finished, I will notice that I have respected this tone while I progressively altered and transformed all the others. The expressive aspect of colours imposes itself on me in a purely instinctive way. To paint an autumn landscape, I will not try to remember what colours suit this season, I will be inspired only by the sensation that the season arouses in me; the icy purity of the sour blue sky will express the season just as well as the nuances of foliage. My sensation itself may vary, the autumn may be soft and warm like a continuation of summer, or quite cool with a cold sky and lemon yellow trees that give a chilly impression and already announce winter. My choice of colours does not rest on any scientific theory; it is based on observation, on sensitivity, on felt experiences.” See Flam, Matisse on Art, 38. ↩

-

Flam, Matisse on Art, 36. ↩

-

Flam, Matisse on Art, 37. Liu Kang also quoted the same passage from Matisse’s “Notes of a Painter”. See Liu, Liu Kang at 87, 31–32. ↩

-

Chen Wen Hsi, Liu Kang’s peer and one of the four artists in the joint exhibition, recalled: “People said that it [Post-Impressionism] was the school of ‘external appearance’. That is, they paid attention to light and air. So, while Impressionist works were fuzzy and did not have very clear lines, the Post-Impressionists had clearer and broader strokes. There was a lack of subjectivity in this. It is like painting something by referring to the lines of symmetry. After this, there were Fauvism and Cubism. Here, it is the application of subjectivity. You are gradually applying subjectivity to control the look of the picture.” See Chen Wen Hsi’s oral history interview transcript Part 2 in Chen Wenxi, Convergences – Chen Wen Hsi Centennial Exhibition (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 2006), 20. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 759.95957 CHE-[LKY]) ↩

-

Liu, Liu Kang at 87, 35. ↩

-

Quoting from Liu, 刘抗文集, 213, and cited by Kwok Kian Chow, Journeys: Liu Kang and His Art (Singapore: National Arts Council and Singapore Art Museum, 2000), 14. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 759.95957 LIU) ↩

-

Ralph Crozier, “Post Impressionists in Pre-War Shanghai: The Juelanshe (Storm Society) and the Fate of Modernism in Republican China,” in Modernity in Asian Art, ed. John Clark (Australia: Wild Peony Limited, 1993), 136. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RART 709.5 MOD) ↩

-

Mayching Kao, “The Quest for New Art,” in Twentieth-Century Chinese Painting, ed. Mayching Kao (Hong Kong; New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 130. ↩

-

Ong Zhen Min, “A History of the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (1938–1990)” (Master’s thesis, National University of Singapore, 2006), 26–30, http://scholarbank.nus.edu.sg/handle/10635/15776. ↩

-

Liu Kang once said, “China has remained my artistic vision… I am always conscious of the vastness of the country, the sense of scale, the depth of vision, the inner strength and greatness which characterise Chinese culture and art.” Quoting from Gretchen Mahbubani, “Journey of a Pioneer Artist,” Straits Times, 1 December 1981, 1. (From NewspaperSG), in Liu, [Liu Kang at 87](https://eservice.nlb.gov.sg/redir/itemdetails?bid=8726393), x. ↩

-

Quoting from “Postscript,” in Liu Kang, The Paintings of Liu Kang (Singapore: National Museum, Singapore, 1981), x. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 759.95957 LIU); Chia, “Introduction,” 17. ↩

-

Liu, Liu Kang at 87, 27 ↩

-

Chia, “Introduction,” 10. ↩

-

Quoting from “Preface III,” in Liu, The Paintings of Liu Kang; Chia, “Introduction,” 21. ↩

-

Chia, “Introduction,” 17. ↩

-

Kwok, Channels and Confluences, 52. ↩

-

Kwok Kian Chow, From Ritual to Romance – Paintings Inspired by Bali (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 1994), 42. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 759.9598 SI-[LK]). ↩

-

There were multiple players such as art promoters like Frank Sullivan, art historians like Michael Sullivan, collectors like Loke Wan Tho, and gallery and art supply shop owners like Tay Long. There was also a growing art market in the 1950s. For instance, paintings, worth a record $9,800, were sold at a joint show by Liu Kang, Chen Wen Hsi, Cheong Soo Pieng and Chen Chong Swee in 1951. See Kwok, Channels and Confluences, 40, 69. ↩