The Netherlands East Indies 1926 Communist Revolt Revisited

By Kankan Xie

In the Dutch East Indies, the demeanour of the native

towards the European has passed by successive stages from an almost

abject deference to a thinly veiled hostility. The Dutch colonists

are accordingly anxious and restive about the ultimate outcome

of the present “ethical” policy.1 Knowledge of the natives’ history

encourages the colonists in the view that the extreme plasticity of the

native character renders outside influences particularly powerful

in Java, and that it will prove disastrous if the Government stands

weakly aside in the presence of subversive agitation.2

Introduction

On 7 October 1926, The Singapore Free Press (SFP), a popular Englishlanguage newspaper in the Straits Settlements, reprinted a long opinion piece from London’s The Times. Entitled “Dutch Policy in Java: Propaganda and the Native”, the article discussed the ongoing “communist disturbances” in the nearby Netherlands East Indies (NEI ). A keen observer, the anonymous author reviewed in great detail the history of the Archipelago and analysed various immigrant groups in colonial society at that time. He pointed out that people in the NEI were open to foreign influences, which provided radical movements – such as Chinese anti-imperialism and Arabian Islamicism – with fertile grounds on which to grow.

As the Dutch gradually lost their prestige in the natives’ eyes by “perpetrating acts of injustice and, often, uncontrolled violence”, extremist ideologies such as communism gained significant support from the indigenous population.3 The author indicated that communist propagandists had successfully worked their way into schools, trade unions, government departments and military units. With the growing impudence of the local press and the increase in disruptive activities, it was evident that extremism had experienced a rapid upsurge in recent years. The article ended by exhorting the Dutch to take sterner measures to curb this dangerous communist agitation.4

Printed alongside advertisements on the newspaper’s page six, the opinion piece probably did not receive the attention it deserved despite its persuasive analysis and alarmist warnings. A month later, a major communist revolt broke out in Batavia, followed by similar uprisings in Bantam and West Sumatra. How could the writer have made such an accurate prediction a month in advance while the Dutch colonial administration seemed caught unprepared when the uprising happened? Why did the SFP print the article, or rather, why did political issues in the NEI even matter to newspaper readers in British Malaya?

Through NewspaperSG, a digital newspaper database developed and managed by the National Library Board (NL B) of Singapore, this paper aims to add more nuanced views to the understanding of the 1926/27 communist insurrections in the NEI , especially their broader impact on Malaya. This paper argues that partly because of the extensive public discussions surrounding the NEI insurrections, as well as important lessons learned from their Dutch counterparts, the British administration’s anticommunist measures predated the formal establishment of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) in 1930. As a result of the British authorities’ effective surveillance and policing work, the MCP struggled for its survival from its inception and never had a real chance to pose serious threats to the colonial regime before World War II (WWII ).

A few scholars have studied the history of early communist movements in the NEI and British Malaya.5 Ruth McVey’s The Rise of Indonesian Communism (1965) is by far the most comprehensive account of the origins of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI ) until its disintegration in 1927. Using both Dutch and Indonesian materials, McVey has produced a very detailed analysis of the 1926/27 revolts and the government’s systematic suppression of them. The year 1927 is a convenient ending point in McVey’s narrative because the PKI was forced underground and would not play a significant role in Indonesian politics until many years later. Yong Ching Fatt’s The Origins of Malayan Communism (1997) investigates the movement on the British side of the Malacca Straits. Using both English and Chinese sources, Yong traces the Chinese roots of the early communist organisations in Malaya. Both McVey and Yong briefly mention the communist movements of the “other side” in their respective works.

Cheah Boon Kheng (1992) took an important step forward by conducting preliminary research into the links between the two movements. Besides an essay-length summary of these connections, Cheah also reproduced a number of documents that illustrate the MCP’s Indonesian connections in the early years of the organisation’s establishment (1930), which could serve as important signposts for further exploration. Despite his interesting findings regarding the communists’ networks across the British and Dutch colonies, Cheah’s work does not grapple with the wider socio-political impacts of these early movements beyond the limited connections of individuals, which left a gap for further studies.

Many historians consider the PKI uprisings as important precursors of Indonesia’s nationalist movement, which ultimately led to the country’s independence.6 When it comes to the actual course of events, however, existing narratives tend to describe the abortive revolts as ill-prepared, poorly organised and easily suppressed – and consequently, of limited impact in shaking the foundation of the Dutch colonial regime.7 It is also commonly understood that in the aftermath of the rebellions, Dutch authorities dealt a crushing blow to the PKI and its associated organisations by carrying out large-scale arrests, imprisonments, executions and banishments. Beyond these facts, however, very little attention has been paid to the deeper meanings that the revolt revealed. As the following sections will demonstrate, the movement created enormous anxiety in the NEI , which forced the Dutch colonial government to act with a strong hand. Moreover, with frequent exchanges of information and personnel across the Malacca Straits, the NEI uprisings also generated considerable uneasiness in British Malaya.

More Than a Source: NewspaperSG as a Method

Due to communist organisations’ illegal status in both the NEI and British Malaya, and the fact that many documents did not survive WWII and the post-independence era that followed, historians have lacked a large source base to understand early communist movements in the region.8 For this reason, newspapers can serve as valuable sources and make up for the shortage of original party documents. Moreover, they also add more nuanced views to the one-sided narratives that were solely based on official documents of the colonial archives. Paradoxically, newspapers’ massive information can also impede the efficiency of historical research as researchers often spend a lot of time sifting through information to find something significant.

First launched in March 2009, the digital newspaper archive NewspaperSG presents new possibilities in approaching historical issues in Singapore and the surrounding areas. With its Optical Character Recognition (OCR) feature, scholars can now perform keyword searches to locate desired content in 43 newspapers published in Singapore between 1831 and 2006.9 For this paper, newspapers used include the SFP, The Straits Times (ST), Malaya Tribune (MT ) and Malayan Saturday Post (MSP ).10 The Singapore press received their information from various sources such as Reuters, its Dutch counterpart Aneta and local NEI newspapers in multiple languages. ST and SFP also hired their own correspondents, who regularly wrote reports for the papers’ special NEI columns entitled “The Week in Java”, “Java Notes” and “Java Press Cables”.11

In addition to the ease of access to the vast amount of information, digital archives have a lot more to offer than traditional newspapers in many other regards. For instance, NewspaperSG allows researchers to keep track of events’ developments in a way more similar to how original readers would have received those messages: breaking news was sometimes based on rumours and invalidated reports from other sources; reliable details were often not revealed until much later. With frequent repetitions, corrections, validations, negations, and more often than not, contradictions in a series of news reports, a reader’s perception of an event could be very different from its reality. Similarly, how readers digest news can be influenced by what they read in conjunction with the news itself. In other words, as far as readers’ impressions were concerned, the textual context in which the news was reported probably played no less significant a role than the larger socio-political context in which the event actually took place. While such nuances are very difficult to scrutinise by flipping through traditional newspapers, researchers are able to make better sense of complex issues by tracing the progression of time and capturing historical moments in the virtual pages of digital archives.

Furthermore, digital newspaper archives open the door for scholars to conduct quantitative textual analysis in addition to the content-focused “close reading”.12 The latest version of NewspaperSG has a simple yet powerful analytic tool called the Search Term Visualiser, through which researchers are able to grasp the changing trends of word use in Singapore media during the selected period. The following section includes a few graphs generated from NewspaperSG and illustrates how the Singapore press responded to communist movements in the mid-1920s in general and the 1926 NEI communist revolt in particular.

Despite the numerous advantages of using digital newspaper archives, one should be aware of its shortcomings. For example, the current OCR technology is far from perfect. Closely associated with the present state of the original newspapers (or microfilms), the outcome of digitisation may vary considerably. Even the most advanced digital scanner cannot guarantee the quality of the digitised materials. The latest version of NewspaperSG has fairly good coverage of English sources with a relatively high level of OCR accuracy. Searches in other languages, however, still require further optimisation due to greater technical challenges to performing OCR for non-romanised characters. As a result, one should be conscious of the risk of basing their analysis primarily on a handful of English-language newspapers published in an extremely heterogeneous colonial society. ST, for example, enjoyed the reputation of being Malaya’s leading newspaper. Popular only among the English-educated elites, however, it had a readership of only around 6,000 to 7,000 towards the end of the 1920s.13 This is a low number when compared to Singapore’s total population – around 400,000 – at the time.14 For this reason, this research should be supplemented with other materials.

Making Sense of the Numbers

People commonly associate the origins of communist activity in British Malaya with the ethnic Chinese community and political influences from mainland China. Such an association is likely derived from the fact that the membership of the MCP was predominantly ethnic Chinese. although the MCP was not formally established until 1930, Yong Ching Fatt suggests that Chinese communists had been operating in British Malaya as early as 1921.15 Due to contradictions in different sources, the exact founding dates of malaya’s early communist organisations are difficult to pinpoint. It is generally agreed that the Communist party of China (CPC) established an overseas branch in British Malaya around 1925 to 1926. The CPC branch gradually transformed into the Nanyang (or South Seas) Communist Party (SSCP) in 1927 with the goal of expanding to all parts of the Nanyang area.16 Following this timeline, one would expect an upsurge in the coverage of local communist activities in singapore’s print media from 1925 onwards. The search results from newspaperSG, on the contrary, show a rather complex situation:

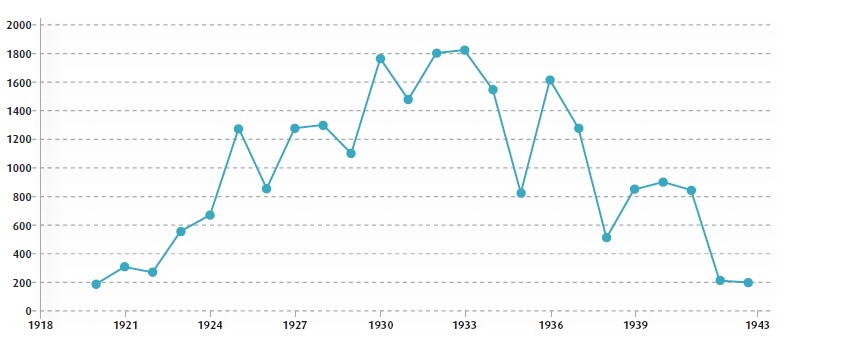

The results of keyword search terms “‘communist(s)’ OR ‘communism’” (Fig. 1) indicate that there was indeed a steady growth (of the use of the terms) that started from 1920.17 The sudden increase in 1925 is also consistent with the alleged establishment of the early communist organisations in malaya. However, when consulted, the relevant newspaper articles were mostly concerned with communist movements outside of British Malaya. Throughout the 1920s, the SSCP was only mentioned twice in 1928 and once in 1929. similarly, there were no results for organisations such as the CPC’s Nanyang Provisional Committee, South Seas Branch Committee, South Seas General Labour Union, and only one result for the Communist Youth League.18 Although it is possible that errors could have distorted the results due to translation or other technical issues, the difference is negligible. The results indicate that early communist organisations had a very limited impact in the public sphere of British Malaya prior to the 1930s.

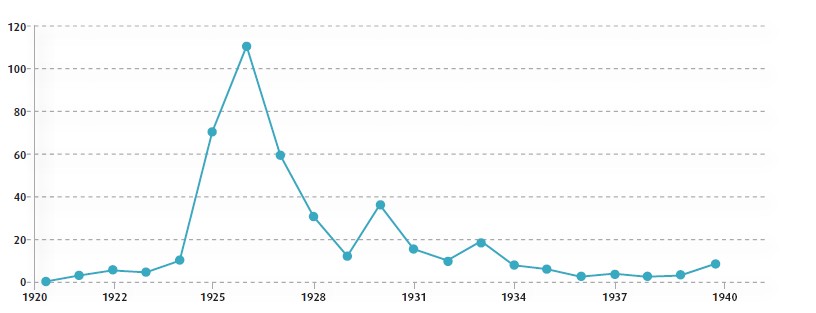

What contributed to the surge of communism-related discussions in singapore newspapers in 1925? Since communist activities in the NEI were frequently mentioned in the mid-1920s, probably because of the PKI revolt, the keyword search terms “‘communist(s)’ AND ‘Java’” are used (Fig. 2).19

From Fig. 2 it is evident that discussions about NEI communist activities surged in 1925 and peaked in 1926.20 Articles that contained both terms “communist(s)” and “Java” grew by 545.5 percent, from 14 in 1924 to 71 in 1925. Is it possible that the media in singapore coincidentally increased the coverage of Java and communism as two separate events? In other words, was the Singapore press actually concerned about communist activities in Java from 1925 to 1927? We can rule out this possibility by using the term “Java” alone (Fig. 3).

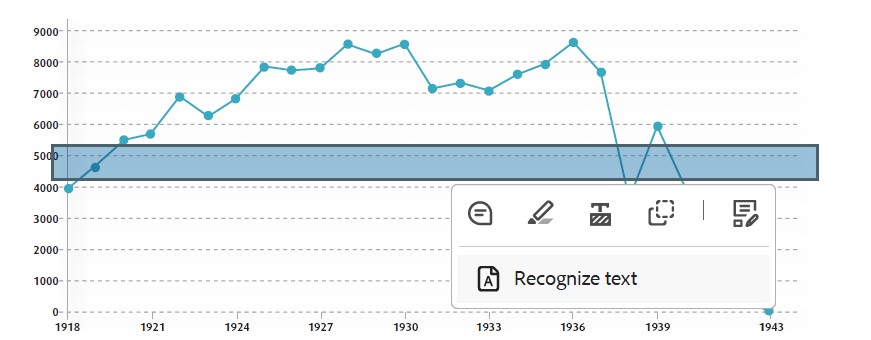

Fig. 3 shows that the term “Java” saw an overall 14.5 percent growth from 6,819 in 1924 to 7,808 in 1925 – a steady increase for sure, but certainly not as pronounced as the terms “‘communist(s)’ AND ‘Java’”.21 Understandably, while the volume of Java-related articles remained constant in the next two years, news reports on communism in Java reached its peak in 1926 and remained high in 1927 due to the PKI insurrections. The media’s growing general interests aside, it is clear that the communist movement in the NEI had already attracted significant attention a year prior to the outbreak of the revolt.

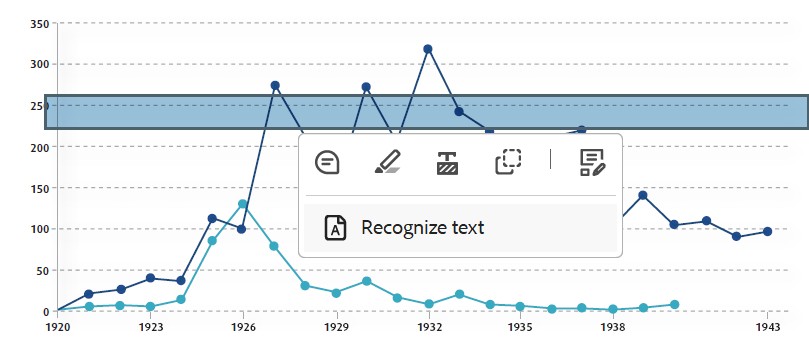

To better understand the impact of the 1926/27 revolt in British Malaya, we can compare the search results of the terms “‘communist(s)’ AND ‘Java’” and “‘communist(s)’ AND ‘China’” (Fig. 4).22 This chart shows that overall, communist activities in China (broadly defined) exerted a far greater influence in British Malaya than their Indonesian counterparts over the years, with the only exception being 1926, presumably due to the PKI revolt. Starting from 1927, however, while China’s influence fluctuated (at a relatively high level) over the years, the impact of the NEI communist movement became significantly weaker.

Technically speaking, this is a highly problematic comparison, which is due to the inherent shortcomings of digital newspaper archives mentioned earlier. When performing a search with multiple words (Figs. 2 and 4), a lot of “noise”, such as inappropriate text encoding or extraction, may interfere with the desired outcome. For example, some of the search results in Fig. 4 could refer to “China” in one report and “communist(s)” in a different report, but the two reports are somehow interpreted as being in the same newspaper article. It is possible that although both reports are unrelated, such an article might still pop up in a keyword search.

Hence, while NewspaperSG’s search term visualiser is a useful tool in illustrating general trends of word use, it is insufficient to tell a full story. But by performing a basic keyword search, we can draw the preliminary conclusion that the mention of NEI communist activities in the singapore press rapidly increased in 1925 and peaked in 1926, which could be associated with the PKI uprisings. The intensive media coverage on NEI communism preceded the rise of the largely Chinese-influenced local communist organisations in British Malaya. To better understand the impact of the PKI revolt on Malaya, it is worthwhile to delve deeper into the actual content of the newspaper articles.

The 1926 PKI Revolt Through the Eyes of the Singapore Media

Precursor

The situation in the NEI in the first half of 1925 was generally peaceful

except for sporadic clashes between the police and alleged communist

agitators. The NEI colonial authorities managed to arrest a number of

communist leaders for their roles in organising strikes, holding meetings

and delivering “seditious speeches”. The police’s crackdown on communist

activities was effective in major hotbed cities such as Bandung, Surabaya

and Padang.23

From the second half of 1925, there were frequent news reports in the Singapore press concerning Chinese disturbances in Medan, bomb threats across Java, labour disputes in Surabaya and various forms of the Islamic movement.24 These incidents hardly caused the government any serious consequences. There was also no solid evidence suggesting that the PKI was behind all these disturbances. The extremists often operated without coherent party leadership, but their activities were so ubiquitous and unpredictable that fear inevitably arose among government officials and the public. For example, at the end of October 1925, the Singapore press reported several seemingly unrelated acts of unrest that took place in various locations across Java and Sumatra. Some of these events appeared to be labour disputes and some were intertwined with politically sensitive groups such as Chinese coolies, Arabian intellectuals and rebel Acehnese. Without concrete proof, the authorities and media both conveniently attributed the widespread disturbances to communist agitation:

The strike agitation in Surabaya continues… there are rumours

of impending difficulties with the harbour coolies, although the

Surabaya press declares that the [coolies have] declined to answer

the call of communist leaders.25

The Arabian journalist Alfothak, editor of the Arabian paper

Alwivak, which has communist tendencies, is to be deported.26

The strike among the workers of the Tegal Proa Co. was a result

of the discharge of six of their number [sic] who had communist

tendencies.27

Consequently, the colonial authorities adopted stringent anti-communist measures. On top of carrying out numerous crackdowns, the government promised to imprison or banish communist leaders.28 Not only did the authorities forbid the PKI and its associated trade unions from holding meetings, but they also kept a tight rein on the local press.29 The police captured several editors of non-European newspapers for their alleged communist tendencies and for publishing anti-government articles. Besides the Arabian journalist Al-fothak mentioned earlier, other arrests included Lauw Giok Lam, an editor of the Malay-Chinese daily Keng Po in Batavia, and Gondojoewono, an editor of a native paper named Njala.30 The authorities also seized the Bandung-based Chinese newspaper Sin Bin for reprinting an article that had previously appeared in communist publication Soerapati.31

In their attempts to “check communist agitation”, the government issued rigid restrictions on the freedom of assembly among employees in heavily PKI -influenced industries such as shipping, railway and sugar throughout the NEI.32 From March to May 1926, there were at least four instances where the Singapore press reported that the government punished both civil and military personnel for their involvement in PKI activities. The communist suspects were either demoted or fired.33

Such measures notwithstanding, communist disturbances were frequently reported across the NEI. While the PKI and its affiliated trade unions were under strict surveillance, alleged communist propaganda was carried out by local Muslim organisations such as Perserikatan Kommunist Islam (Islamic Communist Association). The colonial government discovered similar movements in Padang, West Sumatra and Makassar, South Celebes.34 The most serious unrest of this sort broke out in mid-February 1926 when approximately 2,000 natives gathered in Solo under the auspices of a Muslim communist organisation called Moalimin:

It was clearly evident that this crowd of Javanese were confirmed

communists and every one of them carried a small red flag with the

insignia of Moscow on it. The so-called religious society Moalimin

preached to its members with considerable zeal the continuance of

the holy war against the Christians and also communistic ideals

which were not in accordance with the Koran.35

While continuous arrests did not seem to eradicate communist disturbances as expected, the authorities’ frequent policing drew considerable scepticism from the public. Local media questioned the government’s credibility in labelling people’s expressions of discontent as being exclusively communist-influenced. Repeated police statements notwithstanding, the so-called communist agitators were rarely brought to trial. With the almost constant lack of convincing information, the government’s attempts to fully crack down on communist activities encountered an enormous crisis of legitimacy in mid-1926, when large-scale unrest broke out on Telo Island off the coast of West Sumatra. As an ST correspondent wrote:

Without wishing to be over-critical, the fact remains that there is,

in regards [sic] the communist activities in the Netherlands Indies,

a deplorable absence of well-proved and reliable statements on

the part of the authorities, which is not what one would expect in

enlightened times.36

Worsening matters was the death of Hadji Misbach, the well-known “Red Haji” who had made his name combining communist propaganda with Islamic doctrine. He had died of black fever around the same period during his banishment in Manokwari, New Guinea. His death triggered wide public discourse regarding the government’s inhumane treatment of dissidents. Some European newspapers even paid tribute to Hadji Misbach for the great sacrifices he made for his political views. The same ST commentator remarked:

… one might well ask if the government has been very wise by

creating in this way a martyr in the eyes of certain groups of the

population. Would it not have been better policy to have facilitated

the agitator’s departure from the colony?37

In the meantime, alleged communist plots kept popping up across the Archipelago.38 Although many of these plots turned out to be insignificant, with colonial authorities usually putting down such unrest without much difficulty, the seemingly ubiquitous communist activities created enormous fear among the public. In September 1926, for example, ST ran a story about the annual Gambir Fair in Batavia:

A few days before the opening there were rumours current that

communists were to attempt bomb outrages and that the police

had made several arrests. These stories, however, seem frightfully

overdone, and find their origin in the fact that recently two

natives were killed by an accidental explosion of what was said to

be a bomb… The European community has a tendency to show

at certain times an exaggerated nervousness, the reports in the

newspapers are not seldom fundamentally incorrect, and to obtain

reliable information from the police is extremely difficult.39

As a result, the tension brought about widespread discontent towards the head of the colonial government, Governor-General Dirk Fock. According to the SFP correspondent, Fock’s autocratic yet ineffective handling of political disturbances made him very unpopular. Articles in the local press criticised the Fock administration for failing to listen to the legitimate demands of the native population. Andries de Graeff arrived in Batavia as the NEI’s new Governor-General in September 1926. In his very first speech before the members of the Volksraad (the People’s Council for the NEI ), de Graeff explained that he would try to deal with communism differently:

As regards the communist movement [de Graeff] was of the

opinion that the solution of this problem should not be sought in

force of arms, although when necessary he would not hesitate to

make use of some, but in his opinion there was much to be done in

connection with the obtaining of closer cooperation with the native

officials and this would be his aim.40

In the months leading up to the PKI revolt in November 1926, the Singapore press published many perceptive critiques of the political situation in the NEI. The insightful analysis presented at the beginning of this paper was by no means unique in Malayan newspapers at the time. For instance, in January 1926 an ST correspondent cast doubt on the Dutch colonial government’s claim that the labour dispute in Surabaya was due exclusively to communist agitation:

… notwithstanding the activities of the police against the so-called

communists, anti-Dutch agitation continues amongst the semi-

intellectual as well as the intellectual classes of the population. It is

noticeable that neither in the People’s Council (Volksraad) nor in

many of the local councils, the native intellectuals are represented,

and in some instances one might well speak of decided non-

cooperation on their part.41

In March, the same newspaper questioned the long-term effectiveness of the wholesale crackdown of the communist movement. The correspondent suggested that while relying on armed measures to deal with disturbances, the government failed to see native issues in “their right proportions”. In other words, the endless raids and arrests merely scratched the surface of the problem, which would never lead to the desired results if the government failed to address the significant issues facing the vast native population.42 In September, the SFP published another lengthy article analysing the contradiction of the increasingly centralised rule of the Dutch colonial government and the growing demand for “decentralisation”, namely seeking greater autonomy for the native population under the Ethical Policy. The article astutely pointed out that the NEI communists were very good at exploiting the political situation:

Communistic and revolutionary propaganda, especially if

conducted by Hajis, the natural leaders of Moslem opinion,

and the teachings of the theosophical societies, have made the

Government policy much harder to carry out.43

The Uprisings

The PKI revolt broke out in Java on Friday, 12 November 1926. Three days later, on Monday, 15 November 1926, news regarding the insurrection appeared in the mainstream Singapore press. Using multiple sources, including a special report from Aneta, ST revealed many details about the uprising. It reported that hundreds of communists entered the native district headman’s house and murdered the chief and two other natives in Menes, Bantam. Shortly after, a European railway surveyor named Benjamin was found murdered. The authorities responded promptly by killing and arresting a large number of rebels.44

The SFP, in contrast, dispassionately reported that the uprising was not at all unexpected for people who had been following the news for the past few weeks. Its correspondent believed that the disturbance was just a small test for the new governor-general and that the situation would not be out of the government’s control.45 Based on news reports from Reuters, MT mentioned the insurrections in West Java only very briefly and, surprisingly, linked it to the recent seizure of two proletarian Chinese schools in Surabaya, which had been found to have maintained close communication with Chinese communists in Guangdong, China.46

In the days that followed, the Singapore press covered the NEI communist uprisings in great detail. While all the mainstream newspapers enjoyed good access to information from multiple sources, the actual reports came across as very confusing. On 16 November, the SFP and MT both published an identical piece (based on Reuters’ telegram from Amsterdam) that reported that the NEI authorities had easily dispersed the mobs and attributed the unrest to the maladministration of former Governor-General Dirk Fock.47 The SFP elaborated that the PKI uprisings were poorly organised and disconnected from each other. The movement lacked careful planning and had no clear purpose. The mobs accomplished very little except cutting off telephone communications and attacking isolated police officers at small stations.48 A day later, the same Reuters story reappeared, which was followed by a contradictory report directly from Batavia.

According to this very brief report, about 500 rebels had attacked a garrison in Laboean. The authorities knew little about the details because communication had been cut off. Military reinforcement had difficulties reaching the destination in time due to broken bridges and blocked roads.49 However, based on the Aneta report, ST reported on the same day that the government had already put down the insurgency in Laboean with 25 rebels killed and 29 arrested. Meanwhile, The Straits Times ran a very worrisome piece from Reuters that the uprisings had spread to Central and East Java. The government arrested 30 communist agitators in Surabaya.50 On 18 November, Aneta confirmed that the situation was still out of control. Entitled “Serious Position in Mid-Java Areas”, MT reported that “numbers of communists swarmed out of the sugar estate areas in order to incite disturbances”.51 A Reuters telegram from Amsterdam, in comparison, delivered a positive message stating that “… there is no cause for anxiety. 49 rebels have surrendered to the local police, and the whole executive of the communist party at Bandung has been arrested”.52

The Dutch authorities suppressed the PKI revolt within a week. Based on Reuters’ telegram from Batavia, ST reported on 20 November that the major insurgency in West Java had been put down, except for minor skirmishes in Bantam. In the absence of official dispatches, the Dutch Colonial Minister Koningsberger assured the media that the insurrection was only a question of sporadic happenings.53 Meanwhile, the SFP published its NEI correspondent’s article, which reviewed the uprising in far greater detail than the previously telegram-based news reports and praised the government for taking prompt measures:

Luckily the authorities were aware that trouble was brewing

several days beforehand; they had taken what measures they could.

It is therefore worthy of mention that whilst fighting was going on

in the old town, the reception at the Palace continued as if nothing

was happening and only a few of the guests were aware that the

expected trouble had broken out. With the exception of the police,

military and a few journalists, nobody in the town knew anything

about the matter until the following morning! Police and military

had done good work whilst Batavia slept.54

Singapore newspapers published many such updates in the following weeks, which provided readers with exhaustive first-hand coverage of the insurrection and the counter-insurgency operations that followed.55 More often than not, the content of these articles was repetitive, but their writers tried to supplement the facts with (sometimes contradictory) personal opinions. For instance, only three days after praising the authorities in the article mentioned earlier, the SFP printed another piece where its correspondent sharply criticised the Dutch administration for lacking “continuity of determination”:

The government handling of the affair was in many ways as erratic

as the organisation and carrying out of the attack. It seemed to

have waited for the revolt, although it knew it was impending

and, having dealt with it, to have become quiescent again until

there were fresh outbursts.56

Despite what had happened, the correspondent regarded the revolt as a series of “attacks of loafers and bad characters led by a few communists”. He suggested that it “[was] more than probable that the actual number of offenders, who were really ‘dyed in the wool’ communists, was comparatively small”. The public, however, could have had a very unbalanced view on such issues, as the articles included widespread rumours and exaggerated details.57

Surprisingly, the Singapore press did not pay much attention to the uprisings in West Sumatra that occurred a month later.58 It was not until mid-January 1927 that the newspapers started to report that the West Sumatra insurgencies were much more severe than Java’s.59 As the colonial authorities continued to take tough measures against the rebels, the subsequent news reports were full of similar stories concerning massive arrests, internment and banishment of the alleged communist agitators.

Discussing Our Neighbours’ Troubles

The Singapore media did not report on the revolt only as a special NEI issue. Newspaper articles regarding the NEI communist uprisings often appeared in conjunction with lengthy discussions of relevant issues in British Malaya. On 16 November 1926, just one day after the Java insurrection was first reported in the Singapore press, a long article in ST expressed sympathy towards the Dutch:

Our Dutch neighbours have been troubled with these sporadic

outbreaks for a considerable time, and we in Malaya sympathise

with the difficult task which has been theirs. What has occurred

serves to emphasise the amazing freedom from agitation and

disaffection which, in the midst of considerable turmoil throughout

the East, [Malaya] has had the good fortune to enjoy. For this we

have to thank not only the sturdy sense of a people who all derive

benefit from a prosperous country but a comparative absence of the

menace of the agitator.60

The author continued by calling for the solidarity of the Malayan people in support of the government’s effort to crack down on similar movements:

What has happened in Java emphasises the need for constant

vigilance, and, as we have said before, there is a duty devolving

upon the leaders of all nationalities in Malaya to support the

authorities in Malaya to support the authorities in seeing that the

would-be sower of sedition has short shrift.61

As more details about the PKI revolt surfaced, there were heated discussions about whether the Indonesian communists plotted the uprisings in Java and Sumatra in Singapore.62 Based on an Aneta telegram, ST first reported that the NEI communists might have used Singapore as a hub to transport firearms.63 About a month later, an ST correspondent cited sources from local NEI newspapers, pointing out that Singapore had been a “rendezvous of communist ringleaders”. PKI leaders frequently stayed and passed through Singapore en route to China, Russia and Europe. Therefore, the correspondent suggested that NEI and Straits Settlements (SS) governments should take coordinated action in arresting communist agitators and hand them over when necessary.64 Dachlan, who was arrested for heading the uprisings in West Java, confessed under interrogation that he had received instructions from two PKI leaders in Singapore.65 An MT reporter, apparently confused by the real causes of the NEI uprisings and the ongoing communist movement in China, passionately wrote that the NEI government needed sympathy and practical help from Malaya to curb the revolution:

The Chinese in Malaya can, and do, exert an influence over the

Chinese of the Dutch Indies. If they value the friendship that has

existed between the many races in both countries, they will lose no

time in making an energetic resistance to the ingress of the subtle

Red poison that is upsetting the balance of young Chinese overseas.

Singapore enjoys the distinction of being a centre of radiation

for many purposes; she can be used as the centre of an anti-Red

campaign by the Chinese, which would greatly assist our Dutch

friends in their job.66

As the NEI government’s wholesale crackdown on communism reached an unprecedented scale, rumours emerged that many PKI fugitives managed to evade arrest by hiding in Singapore. On 18 December 1926, the arrests of Alimin and Musso – two well-known PKI leaders suspected of plotting the Java uprisings – in Singapore substantiated the rumours. ST regarded the event as a positive result of the cooperation between the NEI and SS governments in deterring communism. The article also reported that the NEI media expressed their “wholehearted support” for the authorities in Singapore for taking care of the common interests of the two colonies. In doing so, Singapore was no longer a rendezvous for the NEI communists.67 However, to the Dutch authorities’ great disappointment, the SS government quickly released the two PKI leaders despite repeated extradition requests from the Dutch. The decision was made on the grounds that they did not pose direct threats to the public security of British Malaya.68 Alimin and Musso then proceeded to China and then Russia to study at the Lenin School in the years that followed.69

The case of Alimin and Musso triggered even wider public discussions when Sir Percival Philips, a renowned American journalist, published a series of articles in the British newspaper Daily Mail in December 1927. Based on his in-depth investigations in the NEI earlier that year, Philips wrote that the Dutch authorities were entitled to criticise the SS government for its poor handling of the extradition of Alimin and Musso.70 Philips’ articles immediately attracted the attention of the British parliament. William Ormsby-Gore, the Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies, responded to the queries of the House of Commons that the government was ready to rectify the revised Banishment Ordinance and the phrase “conducive to the public good” would enjoy a much broader interpretation. In other words, by fixing the legislative loopholes, NEI communist agitators would be deemed as dangerous to Malaya as they were to Java and Sumatra.71 ST finally reprinted Philips’ two Daily Mail articles in full towards the end of 1927. In his writings, Philips pointed out that the Soviet influence in the NEI was very dangerous and would pose enormous threats to British Malaya:

While the present state of the communist movement in the

Netherlands Indies gives no particular cause for alarm, its future

is regarded with undisguised anxiety… An important feature

of the anti-communist policy of the (Dutch) government is close

cooperation with the authorities of the Straits Settlements… “Our

interests are identical with yours,” a high official of the government

here said to me, “We have the same problems and are confronted

with the same danger.”72

Philips further suggested that the SS government should learn from their Dutch counterparts in terms of suppressing insurgencies, banning subversive literature and deporting dangerous propagandists. According to him, banishment had proved to be the most effective way of dealing with communism.73

Deterring the spread of communist agitation was not only a political matter, but also a technical one. On 19 January 1927, an SFP correspondent specifically mentioned the superiority of trucks in transporting troops. The Dutch authorities achieved great success in using this method to stamp out insurgencies rapidly in both Java and Sumatra. As railway transportation could be easily disrupted and was not widely accessible, the use of trucks was critical to curbing the insurgencies promptly.74 It was frequently reported that the PKI rebels managed to paralyse official communication by occupying telephone exchange offices and cutting wires during the revolt. To prevent such scenarios from happening in Malaya, a member of the SS Legislative Council suggested that the government build a wireless telegraphic or telephonic system for policing and military purposes.

It was easy to imagine the possibilities of interruption during an

internal disturbance. There had been a recent illustration of this in

the communistic disturbances in Java. One heard that communists

took possession of the telephone exchange in Batavia and that several

of the employees were either forced to join, or willingly joined them.

It was easy to understand that owing to the exposed wire system

employed that during any sudden unexpected rising it would be

possible to throw out of gear, or even temporarily destroy, telephonic

and telegraphic communication in Singapore and generally

throughout the colony, or, for that matter, anywhere in Malaya.75

Technology is often a double-edged sword. Public anxiety was especially palpable when technology was used for communist propaganda. In August 1927, the SFP was shocked to report that Batavia radio amateurs had picked up a radio signal from Moscow, Russia, through which both music and speeches had been broadcasted.76 A month later, a Chinese listener claimed to have picked up transmissions from Vladivostok, Russia. Spoken in very clear Malay, the broadcast urged people in the NEI to rise against the Dutch. The SFP expressed its grave concern over the issue:

If this be true, and there is no reason to discredit it since we know

with what thoroughness and care the Soviet school of propagandists

have been conducted, it is clear that Soviet agitation may become a

matter of serious concern… It would therefore seem that the Soviet

organisation has discovered another and very effective method of

spreading its doctrines abroad, a method much more difficult to

deal with than the method of books and pamphlets, which can be

seized and confiscated.77

Similarly, in an October 1927 article, the SFP reported another similar case, where the NEI authorities discovered that the communists had been using gramophone records as a new means of propaganda.78

Extensive discussions about the PKI uprisings also extended to the cultural sphere in British Malaya. Hubert Banner, a British writer who lived in the NEI during the time of the PKI revolt, released his fictional novel The Mountain of Terror in 1928. Although Banner’s work was first and foremost a romance about a Eurasian girl’s love for an English planter in Java, book reviews in the Singapore press repeatedly highlighted the “up-todate communist intrigue” in the novel and praised Banner for having “real knowledge” about the colony that enabled him to “paint a convincing and authentic picture”.79 Towards the end of 1929, Banner published another novel called Red Cobra, which covered the communist influence in Java in greater detail.80 In response to accusations that Red Cobra exaggerated the impact of communist influence in Java, Banner asserted that his writing was based on historical facts and that the real situation was far worse than what the outside world realised: “A massacre of Chinese in Kudus was traceable to the visit of a white communist agitator. Hadji Hassan and his followers did plot to murder Europeans. Rebels seized the Batavia Telegraph Office and the troops had been out for weeks!”81

In March 1928, the Singapore press voiced their disappointment at the SS authorities for banning the film The Only Way, as its theme of the French Revolution was deemed seditious and thus inappropriate for the Malayan audience:

The Only Way, which was banned here, has successfully passed a

full board of nine censors without dissent for exhibition in Java,

a rider being added that “the production is an excellent one”.

Having regard to the recent communist disturbances in the Dutch

Indies, the above decision is at least notable*.82

Conclusion

Given the relative lack of primary materials, digital newspaper archives such as NewspaperSG provide researchers with a number of alternatives to approach understudied subjects. In addition to serving as valuable sources of information, digital newspaper archives offer additional possibilities to exploit data, including quantitative textual analysis, tracing the development of historical events and making sense of the broader contexts.

The preliminary result of NewspaperSG ’s keyword search shows that public discussions on communism in British Malaya predated the formal establishment of the MCP in 1930. The Singapore press showed particular interest in the communist movement in the NEI from 1925 to 1927. The 1926 PKI revolt generated a far greater influence on British Malaya than the MCP predecessors in the late 1920s.

Content-wise, Singapore’s press coverage on the NEI communist revolt was detailed, comprehensive, up-to-date and multi-faceted. With frequent updates on various forms of communist disturbances since 1925, the outbreak of the 1926 PKI revolt was unsurprising to the Dutch authorities and political observers in Malaya. Although the NEI government quickly suppressed the uprisings in Java and Sumatra, the wholesale crackdown on communism and its relevance to the other side of the Malacca Straits kept public discussions going in Malaya. In this regard, the impact of the poorly organised PKI uprisings was far-reaching, as anxiety about communism persisted and became contagious in the years that followed. As a result, communism as “our neighbours’ trouble” was gradually internalised as “our trouble”, which compelled British authorities to adopt harsh anti-communist measures long before the MCP took shape.

Digitised newspapers are useful sources, but to rely solely on such sources is highly problematic due to some of their inherent shortcomings such as the unbalanced coverage of different languages, variable quality of OCR outcomes, inevitable noise in the original data, as well as inappropriate text encoding and extraction. While it is hoped that the further development of technology will unlock the greater potential of digital archives, further discovery of traditional materials will also be conducive to enriching this research in many significant ways. Ultimately, different sources should complement each other.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Periodicals

Malayan Saturday Post

Malaya Tribune

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser

The Straits Times

Publications

Cheah, Boon Kheng, ed., From PKI to the Comintern, 1924–1941: The Apprenticeship of the Malayan Communist Party: Selected Documents and Discussion. Ithaca: Southeast Asia Program, Cornell University, 1992. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 324.2595075 CHE)

Kahin, George McTurnan. Nationalism and Revolution in Indonesia. Ithaca, N.Y: Southeast Asia Program Publications, Southeast Asia Program, Cornell University, 2003. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.8 KAH)

Lin, Renjun 林任君. Wo men de qi shi nian 我们的七十年 [Our 70 years: history of leading Chinese newspapers in Singapore]. 新加坡: 新加坡报业控股华文报集团, 1993. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RCO 079.5957 OUR)

McVey, Ruth Thomas. The Rise of Indonesian Communism. New York: Cornell University Press, 1965. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 329.9598 MAC)

Partai Komunis Indonesia (PKI). Pemberontakan Nasional Pertama Di Indonesia, 1926 [The first nationalist uprising of Indonesia, 1926]. Djakarta: Jajasan Pembaruan, 1961.

Shiraishi, Takashi. An Age in Motion: Popular Radicalism in Java, 1912–1926. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1990. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.82 SHI)

Turnbull, C. M. Dateline Singapore: 150 Years of The Straits Times. Singapore: Singapore Press Holdings, 1995. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 079.5957 TUR)

Yong, C. F. The Origins of Malayan Communism. Singapore: South Seas Society, 1997. (From National Singapore, call no. RSING 320.9595 YON)

NOTES

-

The Ethical Policy was adopted at the outset of the 20th century with the goal of taking moral responsibility for Dutch subjects. The policy emphasised improving living conditions, creating more opportunities for education and giving more autonomy and greater political rights to the native population. Despite the progress, the policy was often criticised for being too costly and pushing change too rapidly. The Ethical Policy virtually ceased to exist in the 1930s due to the effects of the Great Depression and the burgeoning Indonesian nationalist movement. ↩

-

“Dutch Policy in Java,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 7 October 1926, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

To illustrate his point, the author used two examples. The first was the construction of a road in Java, which cost 8,000 lives; the second was the “1923 Tangerang incident”, in which authorities failed to handle an armed insurrection effectively due to their indecision. He concluded that the Dutch swung from one extreme to another, which undermined their prestige. See “Dutch Policy in Java.” ↩

-

There are a number of other scholars who have conducted research on the NEI or Malayan communist movements in later periods. In this article, I regard early communist movements as movements before WWII. ↩

-

George McTurnan Kahin, Nationalism and Revolution in Indonesia (Ithaca, N.Y: Southeast Asia Program Publications, Southeast Asia Program, Cornell University, 2003), 83–86 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.8 KAH); Takashi Shiraishi, An Age in Motion: Popular Radicalism in Java, 1912–1926 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1990), 339. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.82 SHI) ↩

-

Ruth Thomas McVey, The Rise of Indonesian Communism (New York: Cornell University Press, 1965), xi. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 329.9598 MAC) ↩

-

Cheah Boon Kheng, ed., From PKI to the Comintern, 1924–1941: The Apprenticeship of the Malayan Communist Party: Selected Documents and Discussion (Ithaca: Southeast Asia Program, Cornell University, 1992), 6. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 324.2595075 CHE) ↩

-

There are 43 newspaper titles available with the OCR feature as of 15 May 2017. In addition to searchable content, there are also seven unsearchable “page view only” newspapers. Retrieved from NewspaperSG website: https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/ ↩

-

Due to NewspaperSG’s limited OCR accuracy in the Chinese language, this paper does not include the Chinese-language Nanyang Siang Pau. Singapore’s first independent Malay-language daily Warta Malaya did not emerge until 1930, which was after the period under consideration in this paper. ↩

-

The author consulted The Straits Times and The Singapore Free Press from 1925 to 1930 for this research. ↩

-

Research methods in digital humanities have been undergoing rapid development in recent years. With the help of various tools, skilled researchers can now perform very sophisticated quantitative textual analyses. For this paper, however, I have primarily focused on the content and used the quantitative method to supplement my textual analysis. For this purpose, I used NewspaperSG’s builtin Search Term Visualiser when statistics were involved. ↩

-

C. M. Turnbull, Dateline Singapore: 150 Years of The Straits Times (Singapore: Singapore Press Holdings, 1995), 80–81. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 079.5957 TUR) ↩

-

According to the 1931 Census, Singapore’s total population was 445,778. While Europeans and Eurasians numbered 6,584 and 6,043 respectively, the number of other ethnic groups were much larger: 340,645 Chinese; 43,424 Malays; 41,848 Indians and 7,234 Others. Although the Englishspeaking population was not limited to the Europeans and Eurasians, it is problematic to equate views expressed by the English press to public opinions. The readership of Chinese newspapers was comparable to, if not greater than, that of the English papers. See Lin Renjun 林任君, Wo men de qi shi nian 我们的七十年 [Our 70 years: history of leading Chinese newspapers in Singapore] (新加坡: 新加坡报业控股华文报集团, 1993), 57–58 (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RCO 079.5957 OUR). For a brief summary of the 1931 Census, see “The 1931 Census of Singapore,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 29 May 1931, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Yong C. F., The Origins of Malayan Communism (Singapore: South Seas Society, 1997), 41–89. (From National Singapore, call no. RSING 320.9595 YON). The Communist Party of China was established on 1 July 1921. Given that the CPC itself would have still been in its infancy, it is doubtful whether the propaganda was actually carried out under the banner of communism in Malaya in the early years of the 1920s. ↩

-

Cheah, From PKI to the Comintern, 1924–1941, 13–14. ↩

-

Search Term Visualiser, NewspaperSG, accessed February 14, 2017, http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Visualiser?keyword=communist OR communists OR communism&NPT=&CTA=&DF=01/01/1920&DT=31/12/1943. ↩

-

Yong and Cheah discussed these organisations in their work and verifi ed their existence by referring to various sources, including offi cial records in the colonial archives. ↩

-

Singapore newspapers frequently used “Java” (rather than Dutch/Netherlands East Indies) to refer to the Dutch colony as it was the economic and political centre. Java was also where news agencies and correspondents dispatched their reports about the NEI. Therefore, “Java” was used instead of “NEI” in the search. ↩

-

Search Term Visualiser, NewspaperSG, accessed January 11, 2017, http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Visualiser?keyword=communist java&NPT=&CTA=&DF=01/01/1918&DT=01/01/1943. ↩

-

Search Term Visualiser, NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Search Term Visualiser, NewspaperSG. ↩

-

See “Java Sensation,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 21 January 1925, 9; “Communism in Java,” Straits Times, 2 February 1925, 9: “The Week in Java: Communism in Bandoeng,” Straits Times, 7 February 1925, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

For Chinese disturbances see “The Week in Java: The Chinese Agitation,” Straits Times, 21 July 1925, 10 (From NewspaperSG); Bomb threats across Java, see “Java Press Cables,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 3 November 1925, 16 (From NewspaperSG); Labour disputes in Surabaya, see “Java Press Cables: Strike in a Machine Factory; Ice Factory Strike,” Singapore Free Press, 28 November 1925, 7 (From NewspaperSG); Islamic Movement, see “Wireless Telegram: Miscellaneous,” Straits Times, 11 January 1926, 9; “Wireless Telegram: Native Communists Sentenced,” Straits Times, 30 January 1926, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The original text was confusing and did not give further details. It is unclear what the call of the communist leaders was and why the coolies declined to answer. It is clear, however, that the authorities suspected that the communists were behind the strike, although not all the coolies actually followed the PKI instructions. See “Java Press Cables: Arab Conflict,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 31 October 1925, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Bomb threats across Java, see “Java Press Cables.” ↩

-

“The Week in Java: The Strikes in Sourabaya,” Straits Times, 10 December 1925, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Java Note: Important Political Measures Taken Against Communists,” Singapore Free Press, 8 December 1925, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Java Notes: The Communist Movement,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 22 September 1925, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Java Press Cables: Chinese Paper Seized,” Singapore Free Press, 22 December 1925, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Untitled,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 27 January 1926, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

See “Java Press Cables: Communists Arrests,” Singapore Free Press, 29 March 1926, 14; “Java Press Cables: Communists in the Army,” Singapore Free Press, 13 April 1926, 7; “Java Notes: The Communists,” Singapore Free Press, 12 May 1926, 7; “Java Press Cables: Communist Arrested,” Singapore Free Press, 13 March 1926, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

For Islamic movements, see “Wireless Telegram: Miscellaneous,” Straits Times, 11 January 1926, 9; “Wireless Telegram: Native Communists Sentenced,” Straits Times, 20 January 1926, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Wireless Telegrams: Communism in Solo,” Straits Times, 23 February 1926, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Java Notes,” Straits Times, 8 June 1926, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Java Notes.” ↩

-

From July to September 1926, colonial authorities uncovered a number of so-called communist plots: in Sabang, see “Java Notes: A Plot at Sabang,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 13 July 1926, 7; in Tegal, see “Java Notes: The Riot at Tegal,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 10 August 1926, 7; in Bantam, see “Java Notes: Unrest in Bantam,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 24 August 1926, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Week in Java,” Straits Times, 3 September 1926, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Java Notes: The Arrival of the New Governor,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 14 September 1926, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Week in Java,” Straits Times, 9 January 1926, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Java Notes: The Acheen Affair,” Singapore Free Press, 17 March 1926, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Dutch Colonial Policy,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 24 September 1926, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Java Disorders,” Straits Times, 15 November 1926, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Singapore Free Press: Weekend Comment,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 15 November 1926, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Javanese Riots,” Malaya Tribune, 15 November 1926, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Javanese Riots,” Malaya Tribune, 16 November 1926, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Communist Riots in Batavia,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 16 November 1926, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Java Communist Outbreak,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 17 November 1926, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Java Disorders,” Straits Times, 17 November 1926, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Java Disorders: Disturbances Incited on Sugar Estates,” Straits Times, 18 November 1926, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Javanese Rising,” Malaya Tribune, 18 November 1926, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Java Disorders,” Straits Times, 20 November 1926, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Communist Outbreak in Java,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 20 November 1926, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

See “Singapore Free Press: The Java Revolt,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 23 November 1926, 8; “The Riots in Java,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 29 November 1926, 11; “Java Notes,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 30 November 1926, 16; “Java Disorders,” Straits Times, 27 November 1926, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The insurgencies were briefly mentioned as “minor irregularities” in Singapore newspapers in December. See “Java Notes: The Communist Action,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 15 December 1926, 3; “Java Notes,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 21 December 1926, 16; “Moscow and Java,” Straits Times, 21 December 1926, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Java Notes,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 13 January 1927, 14; “Java Notes,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 19 January 1927, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Straits Times: The Work of Agitators,” Straits Times, 16 November 1926, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

According to Ruth McVey’s research, prior to the outbreak of the PKI revolt, at least three centres claimed authority over the party: Tan Malaka and his supporters in Malaya, the revolutionary committee in Batavia and the least important official headquarters in Bandung. It was discovered that the Batavia branch revolted without consent from the real party leadership. See McVey, The Rise of Indonesian Communism, 334. ↩

-

“Java Disorders.” ↩

-

“Moscow and Java.” ↩

-

The two PKI leaders in Singapore were probably Sardjono and Kusnogunoko, see “Communism in Java,” Straits Times, 22 January 1927, 9 (From NewspaperSG); and Partai Komunis Indonesia (PKI), Pemberontakan Nasional Pertama Di Indonesia, 1926 [The first nationalist uprising of Indonesia, 1926] (Djakarta: Jajasan Pembaruan, 1961) or see Chinese-language edition: Yindunixiya di yi ci min zu qi yi (1926 nian) 印度尼西亚第一次民族起义(1926年) [Institute of history of the communist party of Indonesia] (北京: 世界知识出版社, 1963). (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RUR 335.4309598 PEM) ↩

-

“Communism in the Indies,” Malaya Tribune, 25 January 1927, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Java Communists,” Straits Times, 7 January 1927, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Java Communists,” Straits Times, 15 December 1927, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

McVey, The Rise of Indonesian Communism, 202. ↩

-

The Singapore press first briefly reported about Philips’ article in “Communists in Java,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 3 December 1927, 11 (From NewspaperSG). The full texts of the two articles were not reprinted until 27 and 31 December respectively. ↩

-

See “Singapore Free Press: Communists and the Straits,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 7 December 1927, 10 (From NewspaperSG); “Java Communists.” ↩

-

“Playthings of the Reds,” Straits Times, 31 December 1927, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“TO BOLSHEVISE ASIA,” Straits Times, 27 December 1927, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Java Notes.” ↩

-

“Legislative Council,” Straits Times, 14 December 1926, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Java Notes: Communism by Wireless,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 4 August 1927, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Singapore Free Press: Wireless Propaganda,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 6 September 1927, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Java Notes: Matters Communist,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 26 October 1927, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“New Books,” Straits Times, 10 November 1928, 15; “Literary Notes,” Malaya Tribune, 29 April 1929, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“A Literary Page – New Books Reviewed: A Java Novel,” Straits Times, 22 November 1929, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Notes of the Day: The “Reds” in Java,” Straits Times, 14 February 1930, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Untitled,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 11 March 1927, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩