An Old Teochew Oral Account Sheds New Light on the 1819 Founding of Singapore

By Jason Heng

Introduction: The Chinese in Singapore Before Raffles

The landing of Sir Stamford Raffles at the Singapore River on 28 January 1819 is often seen as the turning point of Singapore’s history, marking its modern era. To no small extent, this has been influenced by the Englishman’s writings back home, which included his famous declarations to the Duchess of Somerset of Singapore as “my new colony” and “a child of my own and I have made it what it is”.1 Other luminary patrons were briefed that the settlement’s original population “scarcely amounted to 200” before it surged to “not less than 3,000” in three months, and that in over a year, the “insignificant fishing village” had been transformed into a “port… surrounded by an extensive town” with “ten or twelve thousand souls, principally Chinese”.2

These testimonies invariably aggrandised Raffles’ personal role in the founding of Singapore. However, a recently published private correspondence dated 8 January 1819 between Raffles and East India Company (EIC) Governor General Lord Hastings, reveals his possession, at least nine days before sailing from Penang to Singapore, of intelligence that his intended destination already had “about 2,000 inhabitants upon it (new settlers) under a respectable Chief” [text in parentheses in original].3 Conspicuously, all his known communication to England excluded this information; for instance, Raffles had later told Hastings that “when the British flag was first hoisted, there were not perhaps fifty-three Chinese on the island”.4

Within two days of his arrival, Raffles had the written agreement of the local ruler, Temenggong Abdul Rahman, to set up an EI C trading factory. This was formalised by a treaty with the former Johor Sultanate crown prince Tengku Long (whom he assented to recognise as Sultan Hussein Shah) and the Temenggong on 6 February 1819.5 Exactly a week later, Raffles prepared an official report to the EIC Supreme Government in Calcutta that contained, among other insights, a full description of ongoing economic activities in Singapore. In his own words:

… the industrious Chinese are already established in the interior

and may soon be expected to supply vegetables, and c., and c., equal

to the demand. The port is plentifully supplied with fish and turtle,

which are said to be more abundant here than in any part of the

archipelago. Rice, salt, and other necessaries are always procurable

from Siam, the granary of the Malay tribes in this quarter.

Timber abounds in the island and its vicinity; a large part of the

population are already engaged in building boats and vessels, and

the Chinese of whom some are already engaged in smelting the

ore brought from the tin mines on the neighbouring islands, and

others employed as cultivators and artificers, may soon be expected

to increase in a number proportionate to the wants and interests of

the settlement….6

Without question these were commercial activities beyond the scale of an “insignificant fishing village” and the Chinese participation in them was not inconsequential.

Between giving two contrasting pictures – one of a sleepy village with 200 persons and another of a bustling new settlement of 2,000 individuals – Raffles privately admitted to a merchant in Penang that Singapore had, as of end-January 1819, “only five hundred” persons who were “inhabitants from Malacca and Rhio that are gone there”.7 This was as close as he got to the truth; the first resident of Singapore, William Farquhar, independently confirmed many years later that the Temenggong was found established with “four or five hundred followers”.8

Another member of the 1819 expedition party, Captain John Crawford, recalled in his diary an encounter with “upwards of 100” Chinese, who offered themselves as labourers and were duly hired to cut down rank grass and root out jungle near the British tents.9

Eminent Raffles scholar John Bastin considered Raffles’ acknowledgement of the Chinese in his February 1819 official report “an interesting reference”.10

However, outside of writings that completely overlook them, these Chinese have barely merited more than passing mentions by Singapore historians, so as to stress the smallness of their number.11 In a recent instance, they were even assumed to be “very lost”.12 The implication is that existing accounts of Singapore’s modern founding have drawn on incomplete information about an anonymous, but important, group of Chinese.

An Old Teochew Oral Account

The Teochews hailing from the eastern Guangdong Province were one of the first resident groups of Chinese in Singapore. In the earliest-known written description of the Chinese in Singapore by one of its own members, prominent Teochew merchant Seah Eu Chin, it was reported in 1848 that his “tribe” was then the largest, accounting for 19,000 out of 40,000 Chinese in total.13

At present, nearly all published knowledge about the Singapore Teochew community in the early half of the 19th century centres on Seah’s life and his success as a plantation owner that earned him the nickname “Gambier King”. However, Seah only arrived in Singapore in 1823 at a relatively young age of 18, and a handful of late-1940s and early-1950s publications by the Teochew community expressed an unequivocal belief that the Teochews had been established in Singapore even before a port was opened in 1819.14

If true, then there is a good possibility that the first group of Chinese in Singapore reported by Raffles were Teochew. However, there had been no writings to support the grounds for the Teochews’ conviction that their forefathers were in Singapore before Raffles, until an elucidation of how the Teochews first arrived was presented in the 1950 publication Teo-chews in Malaya (《马来亚潮侨通鉴》).

The editor of this encyclopaedic title, which focused on the background and activities of the Teochew migrant communities in Singapore and Malaya, was Phua Chye Long (潘醒农),15 a publisher and an office-bearer with Ngee Ann Kongsi and Singapore Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan.16 He was also the author of the relevant text that was attributed to the oral tradition. It appears over two separate passages in the book and an English translation of the first passage is as follows:

It is said that before Englishman Sir Raffles arrived, Singapore

was a fishing village and a Malay sultan resided in Sek Lak Mung

(石叻门).17

There were more than 10 persons from Hai Ior (海阳),18 who were

all tragically killed by the Malays; and subsequently Teochew

sojourners were recruited from Siam, and they lived at Sua Kia

Deng (山仔顶, meaning “top of the little hill” ), which is the Wak

Hai Cheng Bio (粤海清庙) compound of today.19

From Dang Khoi, Ampou (庵埠东溪), hailed two men, Heng Kim

(王钦, a descendant of Tsap Poih Buan Seng [十八万胜]) and Heng

Hong Sung (王丰顺), who sailed to Singapore before others and, as

leaders of the Teochew sojourners, built Wak Hai Cheng Bio and

formed Ngee Ann Kun (义安郡).20

Thereafter, whenever Teochew sojourners sailed south to Singapore,

the red-head junks would moor in front of the temple,21 and [the

migrants] would put up inside the premises, so that whoever

wanted to hire a shop assistant could negotiate with them there.

Until 1819 when Sir Raffles obtained a lease for Singapore, Sung

Heng (顺兴) gambier plantation was their base; this is today’s

Uang Ge Sua (王家山),22 and by then the number of the Teochew

sojourners was already in the thousands.23

The second write-up of what we may term, for the purposes of discussion, as the “Teochew oral account” similarly told of two waves of arrival of the Teochew people in Singapore, before Raffles arrived in 1819. A translation of it reads:

According to the oral traditions, at the beginning a group of more

than 10 persons from Hai Ior travelled afar to Singapore, but

they were all tragically killed by local Malays. Subsequently a

number of Teochew sojourners came from Siam, and they lived at

Sua Kia Deng (that is the present Wak Hai Cheng Bio grounds)

and around Boat Quay, which became the base of the Teochew

sojourners in Singapore.

At that time the Malay ruler’s seat was at today’s Sek Lak Mung,

and though the Chinese and the natives were mixed freely, there

was peace among them.

Hailing from Dang Khoi, Ampou were Heng Kim and Heng

Hong Sung, who were the descendants of Tsap Poih Buan Seng,

a forerunner of the junk trade, and in his day leader of the

Teochew sojourners.

Thereafter the Teochew sojourners migrated south continuously and

their numbers grew by the day…24

Except for uncertainty over whether only Heng Kim, or both Heng Kim and Heng Hong Sung, descended from Tsap Poih Buan Seng, the two texts can be seen to adhere to a coherent storyline.

Notwithstanding references to him as a sultan, the unnamed Malay ruler can be readily identified as Temenggong Abdul Rahman, the Johor Chief Minister for Justice. Holding hereditary fief over the Singapore Straits and land on both sides (except for Riau and Lingga),25 he moved to Singapore with 150 followers in 1811 and lived by the north bank of the Singapore River (see Map 1) until the British compelled the relocation of his* istana* (palace) to Telok Blangah in 1823.26

Phua confirms this identification in another section of Teo-chews in Malaya, introducing Wak Hai Cheng Bio:

The temple compound that at first covered more than 130 acres was

a grant by the Temenggong-Sultan (图明果苏丹). Later when the

land lease was obtained, the document reflected only the present

site that measures 13,273 square feet in total, as the rest of the land

had been parcelled out by others to build shops and houses.27

Though the Teochew oral account was composed during a period of growing Chinese nationalism and anti-colonial sentiment in the mid-20th century, it is necessary to observe that its balanced presentation does not overtly exalt the Chinese or denigrate the British. To a large part this can be credited to Phua’s standing as a leader in the literary field among the overseas Teochews.28

As testament to its broad acceptance within the Chinese-language scholarship, the Teochew oral account has, in subsequent years, been cited or referenced in a number of Chinese publications concerning the history of the Chinese in Singapore and Teochews overseas.29 Until today, its key points continue to be quoted in local and overseas Chinese-language news reports and online articles.30

Critically, however, Phua’s writings on the activities of Heng Kim, Heng Hong Sung and their followers failed to stir any discussion in mainstream historical circles about the evidence of early Teochew migration to Singapore. This may be due to the Teochew oral account’s limited circulation, its unknown provenance (in accordance to literary practice of Phua’s day, he did not name or profile any of his informants), or its regurgitation by writers who assumed its credibility without providing any further justification. The Teochew oral account may also have been simply ignored because it contradicted popular recognition of Raffles as the founder of modern Singapore.

Oral traditions, being narratives passed down by word-of-mouth over generations, are vulnerable to distortion due to the tendency of transmitters to conflate disparate events, contributing to an inevitable loss of detail over time.

That the Teochew oral account is not without deficiency is emphasised by its sketchy rendering of the alleged ill-fated landing of the men from Hai Ior – even if the deadly incident’s plausibility is supported by Dutch representations of pre-1819 Singapore as a “den of murderers” and of Temenggong Abdul Rahman as the “head of the pirates”.31

Still, the account is significant as it seeks to tell the story of the Chinese who were already in Singapore when Raffles arrived. It cannot be dismissed without an investigation into the writings of the Englishman, Farquhar and other established historical sources, to discover whether the “industrious Chinese” Raffles reported about in February 1819 were indeed Teochew. Should an affirmative answer to this pivotal question be found, the inquiry can then be extended to other major revelations of the Teochew oral account, including its claims that the first Teochews in Singapore came immediately from Siam and were settled at Sua Kia Deng, as well as if their named leaders, Heng Kim and Heng Hong Sung, were actual persons and co-founders of Wak Hai Cheng Bio.

Ascertaining if the First Chinese in Singapore Were Teochew

Although Raffles alluded to being responsible for the early Chinese influx into Singapore on more than one occasion, a review of his surviving writings reveals that he never wrote about them again after his initial communications with Calcutta. In fact, he displayed scarce interest in the Chinese who were in Singapore before him; it was only on his third visit in October 1822 that his secretary, Lieutenant L.N. Hull, enquired of Farquhar on their background.

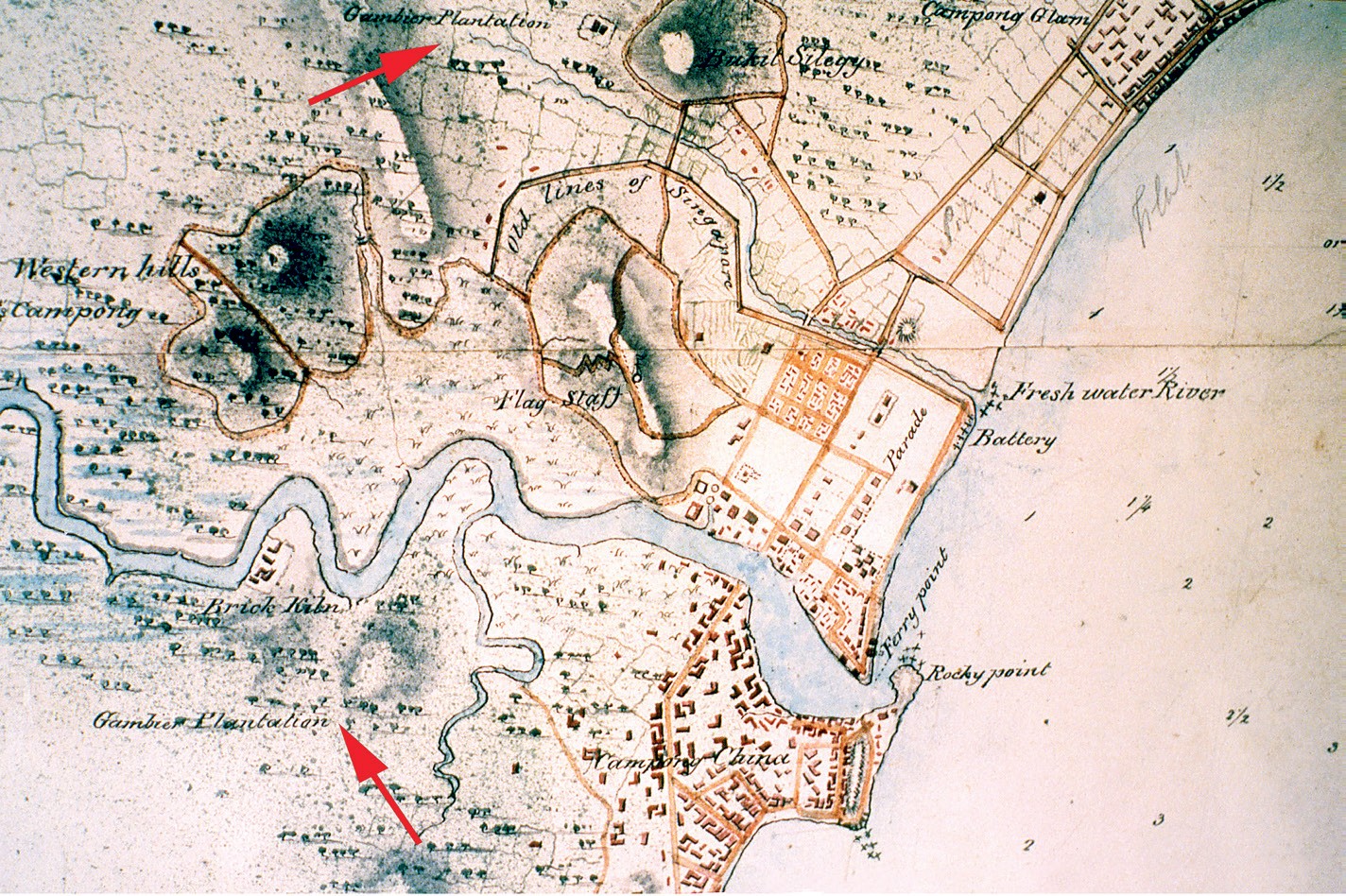

Through Farquhar’s replies, we learn that these men were among “various Malays and Chinese” whom Temenggong Abdul Rahman had granted leave to clear ground for plantations, of which about 20 had commenced prior to British establishment. The resident also observed the location of a Chinese gambier plantation on the western side of Selegie Hill, and another on the northeast portion of a range to the westward of Fort Canning Hill (see Map 2).32

In addition, Farquhar identified the Chinese gambier planters as followers of a “Captain China” (sometimes reported as “China Captain”) and reported that they were settled before the British arrived at the Singapore River’s north bank that later became a cantonment site.33 In 1823, the Captain China was ordered to remove a “Chinese moveable Temple” and “lights from the Great Tree” from a site reserved for a church, which the “Jackson Plan” of 1822 shows to be before Hill Street, at the foot of Fort Canning Hill (see Map 3).34

These revelations match the Teochew oral account’s report concerning a Teochew base around Sung Heng gambier plantation at Fort Canning Hill. Though Farquhar stopped short of calling these gambier planters Teochew, he left an important clue with regards to their leader.

According to Farquhar, the first Captain China of Singapore was a “Canton Chinese”, as opposed to “Amoy Chinese”, whose “great increase” in number later necessitated the appointment of a second captain.35 The historical status of Amoy (now Xiamen) as the principal port of southern Fujian makes certain that the “Amoy Chinese” were the Hokkiens. Intuitively one might suppose the “Canton Chinese” to be Cantonese natives from around Canton (now Guangzhou). However, this is precluded by Seah Eu Chin’s revelation that of all the gambier and pepper planters in Singapore in 1848, 10,000 were Teochews and another 400 were “Macao”.36 This spells out that Cantonese people were not labelled then as they are today, but in accordance to the main port wherefrom they left China before the First Opium War. At the same time, it exhibits a Teochew monopoly over the gambier industry.

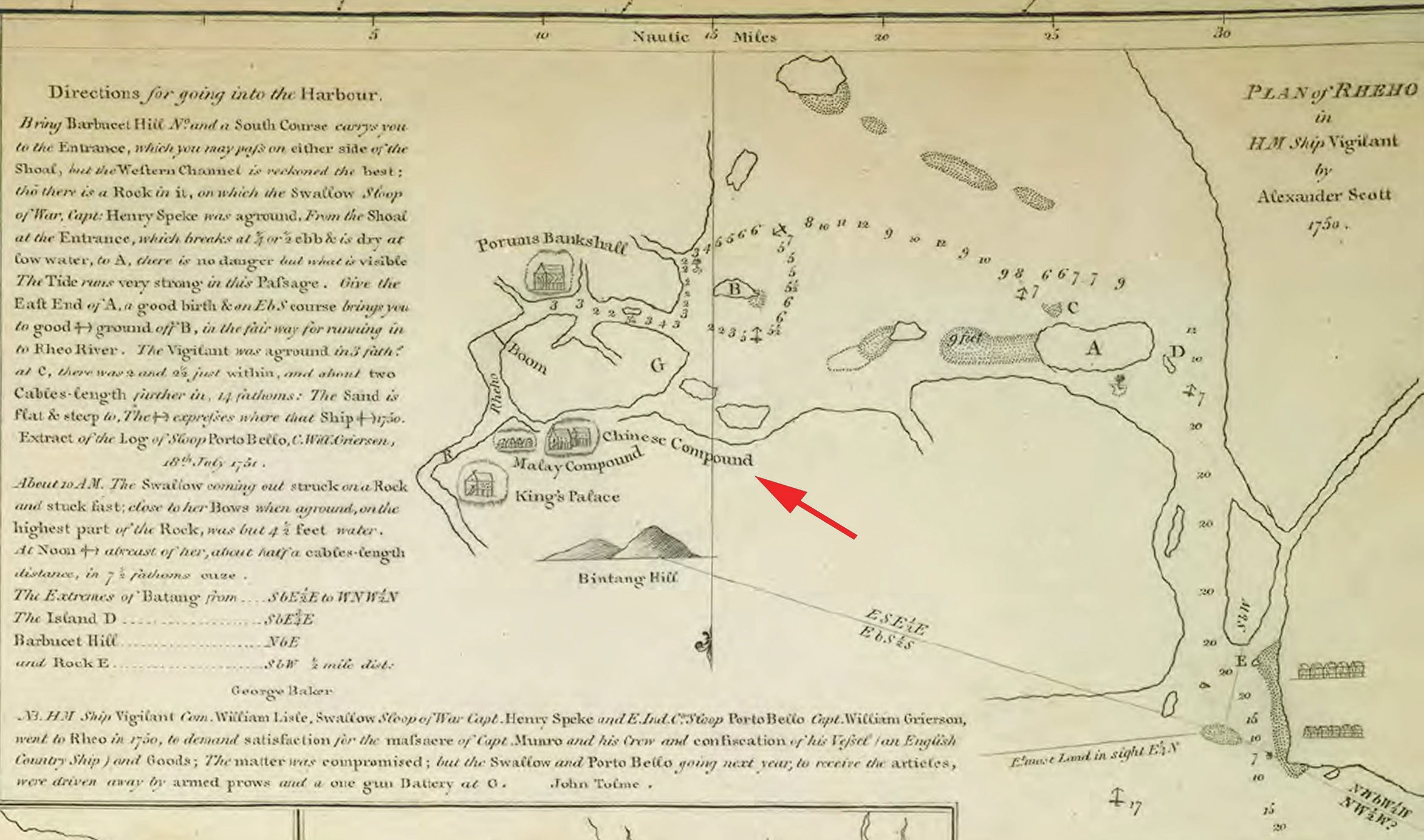

In demand across Southeast Asia as an ingredient for the habitual chewing of betel nut, gambier was significant as the primary export product of nearby Riau before the mid-19th century. As told in the Johor historical chronicles Tuhfat al-Nafis, its commercial cultivation was introduced around 1740 to attract trade from Java and elsewhere, and “Chinese from China” were brought in as labourers in holdings opened by the Malays and Bugis.37 After these natives were driven out by war in the 1780s, the Dutch, who thereafter occupied Riau, reported the takeover of the plantations by two Chinese communities, whom they referred to as “Kantongers” and “Emooijers”.38 Divided by bitter rivalry, they each had a Kapitein (or Captain) residing on opposing river banks at Senggarang and Tanjung Pinang respectively.39

Farquhar’s use of the terms “Canton Chinese” and “Amoy Chinese” were copied from the Dutch and can be derived from Raffles’ disclosure that Singapore’s early inhabitants were “from Malacca and Rhio”. The subsequent Teochew dominance of the Singapore gambier industry– coupled with an assertion by the late local Teochew leader Yeo Chan Boon that Teochew cultivators were established in Riau before the opening of Singapore’s port – strongly suggests that the “Canton Chinese” in Singapore could only be Teochews who moved over from Riau.40

This is supported by a 1976 study on the Chinese in Riau, which found that Senggarang was colloquially known as Teo Bo (潮坡), the “Teochew bank”, and Tanjung Pinang was known as Hok Bo (福坡), the “Hokkien bank”.41

The Immediate Origin of Settlers from Siam

That the first Chinese settlers in Singapore were Teochews from Riau would back the Teochew oral account’s authenticity. But why did it portray the same group of people to be from Siam?

Even though British and Malay sources do not refer to a Siamese representation in early 1819 Singapore, a hidden connection is given away by the kingdom’s “first importance” when the onset of the northeast monsoon at the end of the year brought from various “Eastern ports” the first waves of cargo-laden native trading vessels.42 At the end of Singapore’s maiden trading season of the modern era four months later, its harbour was noted to have “upwards of twenty junks, three of which [were] from China, and two from Cochin China, the rest from Siam and other quarters”.43 The level of trade astonished Farquhar for the British had done nothing to induce it.

Only in January 1820 did a combination of Dutch hostility towards the British occupation of Singapore and the EI C’s financial constraints culminate in instructions from the company’s leadership to Farquhar to consider Singapore “rather as a military post than as a fixed settlement”.44

The junks from Siam were, in fact, operated by Chinese traders. As reported by John Crawfurd, who headed a British embassy to Siam in 1821, it was a hub to “about two hundred” Chinese junks that carried out different branches of trade to ports in China and Southeast Asia. Encouraged by the Siamese government, they also brought thousands of migrant Chinese workers to commence large-scale sugarcane cultivation in plantations after 1809.45 Importantly, among the Chinese in Bangkok, the Teochew were “the most numerous” and “in the forefront of those holding state power and ennoblement”.46 In this context, the Teochew oral account’s intimation of Singapore Teochew leaders Heng Kim and Heng Hong Sun as family relations of Tsap Poih Buan Seng – “a forerunner of the junk trade, and in his day leader of the Teochew sojourners” – becomes telling.

Tsap Poih Buan Seng, according to online and news reports from China, was the moniker of a Teochew named Tan Buan Seng (陈万胜), also known as Tan Seng Lai (陈胜来), who had left his village Tai Mui (岱美) to seek a livelihood in Siam during the reign of Qing dynasty Emperor Qianlong (1736–1796). He eventually became a wealthy junk trader and owned 18 vessels – hence his Teochew nickname of “Eighteen Buan Seng”.47 Beyond this, Tan was recorded in Qing imperial records as the letter-bearer of Siamese monarch King Taksin in a diplomatic mission to Canton to seek a military alliance against Burma in 1775.48 While Tan was probably no longer alive in 1819, his legacy would sufficiently explain the Siamese role in Singapore’s revival as a trading entrepôt.

The reign of King Taksin, who became ruler after the Ayutthaya dynasty was destroyed by Burmese invaders in 1767, was highly significant for the fact that he was the son of a Teochew immigrant. Viewed as a usurper by the country’s old establishment, he built his kingship upon an army served by no small number of his paternal kinsmen and relied on a cohort of trusted Teochew merchants in Bangkok to raise revenue through active overseas trade.49 Of relevance is that Siam was a key trading partner of Riau in the 1770s when Bugis chief Raja Haji was Yam Tuan Muda (viceroy) of the settlement. Many Chinese merchants from Siam came to trade vast quantities of tableware, textiles, silk and rice.50 A deity tablet dedicated to the Chinese junk traders’ titular deity Mazu (妈祖) in 1779 by Chua Iou Kho (蔡耀可) discovered in Senggarang proves a leading Teochew role in this development.51

Hostilities between the Bugis and Dutch government in Melaka in the mid- 1780s ultimately compelled Sultan Mahmud to shift the Johor Sultanate’s seat of power to Lingga. However, Teochew traders from Siam returned to Riau after the old sovereign passed away in 1811 and Raja Jaafar, son of Raja Haji, made himself the sultanate’s strongman by installing Tengku Long’s younger brother as a puppet ruler.52 A wooden plaque was presented in the same year to the Mazu temple in Senggarang by Kapitan Tan Ngueng Pang (陈源放),53 whose Teochew background is revealed by the discovery of the Dutch, upon their return to Riau in 1818, that all the local Chinese were now under a single captain office held by the “Kantonner Chinezen”.54

Despite Raffles’ claim of Singapore as “my new colony”, the concession he obtained from his agreements with the Malays in 1819 had been merely a lease to set up a factory, without the transfer of Singapore’s sovereignty. This state of affairs was clearly reflected in Hailu (海录), the travelogue of Hakka seafarer Hsieh Ch’ing Kao (谢清高), published in 1820. While acknowledging the formation of a trading centre by the British in Singapore, it depicted the place unambiguously as a part of Old Johor (i.e. mainland Johor) and further recorded its reference by natives as Selat, meaning the “straits” in Malay – apparently in relation to Temenggong Abdul Rahman’s fiefdom over the Singapore Straits; and by the Chinese from Fujian and Guangdong as the “new prefecture” (新州府), which apparently stemmed from Tengku Long’s new status as sultan.55

Conceivably, the Teochew oral account is silent about the movement of Teochews from Riau to Singapore because its originators perceived Riau and Singapore to be within the boundaries of a common dominion (that is, the Johor Sultanate).

Settlement at Sua Kia Deng

Following British administration of the harbour at the mouth of Singapore River, the followers of Captain China were settled near Fort Canning Hill, which was subsequently designated for cantonment use – this obliged the settlers to relocate.56 Thereafter, based on the “Arrangement Made for the Singapore Government” signed between Malay and British leaders on 26 June 1819, these Chinese were instructed to “move to the other side of the river, forming a campong [town] from the site of the large bridge down the river, towards the mouth”.57

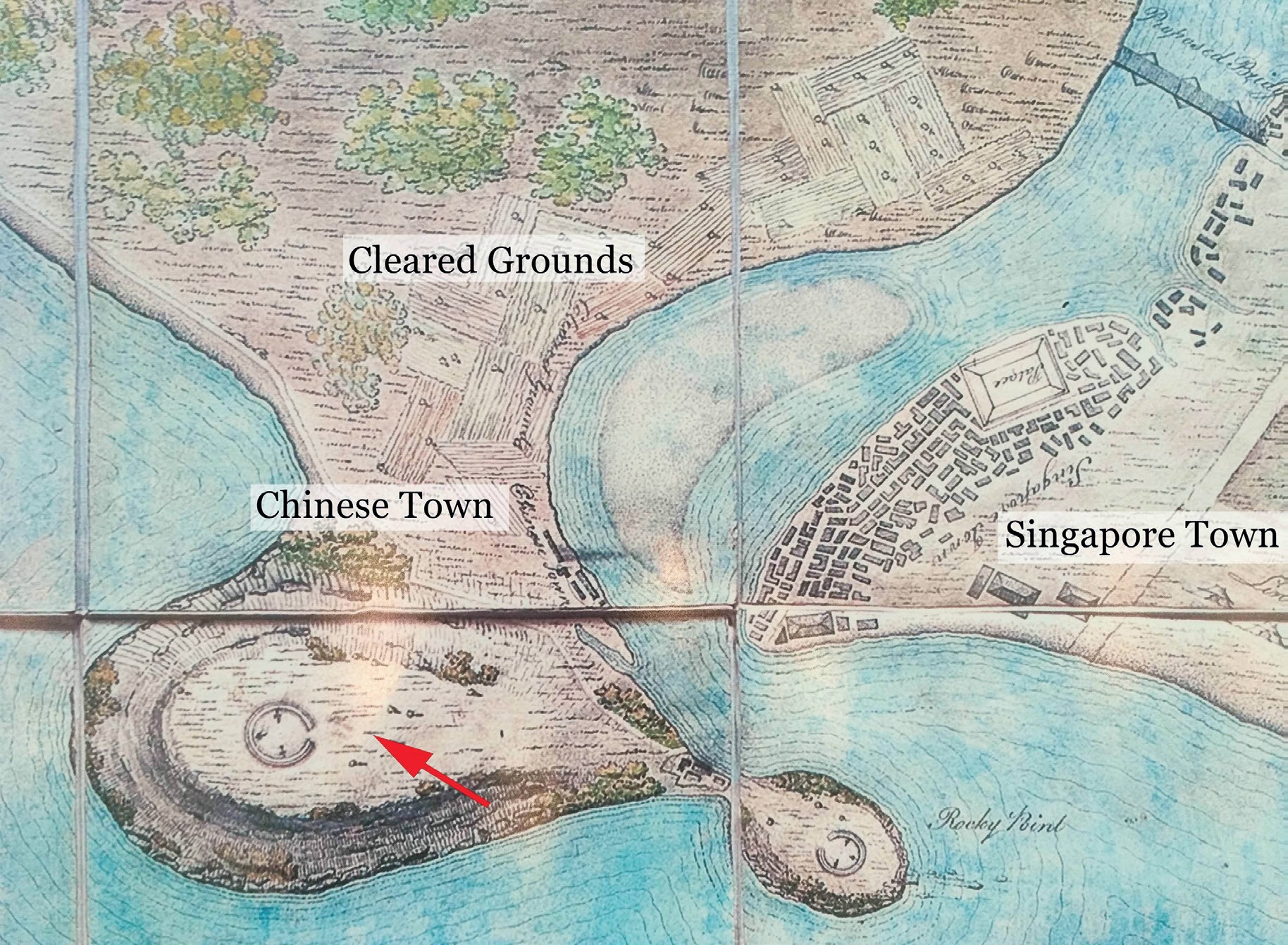

An update by Farquhar at the start of September 1819 informed Raffles that the new precinct was “becoming extensive” and “new streets [had] been laid out to meet the steadily increasing population”.58 Significantly, the Bute Map, drawn around this time and believed to be the earliest-known landward map of modern Singapore (see Map 4), illustrates the limits of this Chinese town and adjoining cleared grounds to encompass both the premises of Wak Hai Cheng Bio and what is now Boat Quay – exactly as told in the Teochew oral account.59

Following the arrival of the first junks from Siam and China, Farquhar reported in March 1820 that “the swampy ground on the opposite side of the river is now almost covered with Chinese houses”.60 However, the distinguished Malay language scribe Munshi Abdullah, who moved from Melaka to settle in Singapore in mid-1819, observed that this side of the Singapore River originally had “no good piece of ground even as much as sixty yards wide, the whole place being covered in deep mud, except only on the hills where the soil was clay”.61 This sheds light that the resident’s statement was probably less of excitement, and more of surprise that there had been any construction at all.

Owing to conditions “where the tide rose ten feet and extended to some distance”, the Boat Quay riverside was, as late as 1822, occupied only by “a few native traders” (a term inclusive of the Chinese) living in rumah rakit, or “raft houses”, erected over the swamp.62 Most of the settlers here would have conceivably built their houses on drier land and the recollection in the Teochew oral account of the place-name “Sua Kia Deng”, or “top of the little hill”, invariably compels attention to a promontory in the locality that Munshi Abdullah remarked somewhat favourably as “a large rise, of moderate elevation”.

Marked on the Bute Map as between the Chinese town and sea, this hill stood at what is presently Raffles Place. Though it was nameless, the traditional settlement of Sua Kia Deng was verified by a letter submitted by the Chinese inhabitants to Raffles in December 1822, confirming that there were 130 houses built on its top.63

Ironically, this letter was a petition against a second eviction notice served to the Teochews after Raffles had planned to level the hill to make way for a new commercial square and use its earth to reclaim what would become Boat Quay.64 This was fulfilled in 1823, and as a result the feature behind the name Sua Kia Deng was not seen on any subsequent maps of Singapore, until the Bute Map resurfaced and was publicly exhibited in the country in

- If anything, the memory of Sua Kia Deng is a tell-tale sign of the age of the oral traditions underlying the Teochew oral account.

The Relation of Captain China with Heng Kim and Heng Hong Sung

If the Teochew oral account’s accuracy is assumed, then Captain China in Farquhar’s statements had to refer to either Heng Kim or Heng Hong Sung. Yet for unknown reasons, the actual name of Captain China was never disclosed in his writings or those of his peers.

Assurance that the portrayals of Heng Kim and Heng Hong Sung were not without basis: it is supported by a positive identification of their purported home, Dang Khoi, with an existing village of same name in the Teochew region located some 20 kilometres from the town of Ampou (see Map 5). Residents there claim lineage from a common ancestor with the surname Heng.65 They also reportedly recall a period of local affluence brought on by shipping and ventures abroad after the mid-Qing dynasty,66 which could be related to the installation of the Teochew prefecture’s chief maritime customs office at Ampou in 1730. All these support the conjecture that both Teochew leaders in Singapore were Dang Khoi natives.

However, this does not corroborate the Teochew oral account’s representation that either Heng Kim, or both men, descended from Tsap Poih Buan Seng, who was found to bear the surname Tan and have roots in the village of Tai Mui.

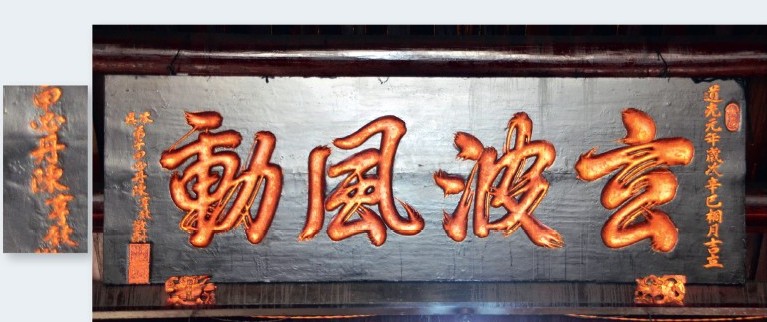

An answer to this conundrum has been elusive in Singapore. Fortunately, a wooden board in Senggarang’s second temple worshipping the martial deity Xuan Tian Shang Di (玄天上帝) has the date of its commission (the commencement of Qing Emperor Daoguang’s reign, 1821) inscribed on both ends, as well as the title and name of its donor Kapitan Tan Heng Kim (陈亨钦) (see Image 1).67 In spoken Teochew, the Chinese characters 王 (from Heng Kim [王钦]), in the context of a surname, and 亨 (from Tan Heng Kim [陈亨钦]), are both pronounced as “heng”.68

Further, a Dutch list of the Teochews who were the Chinese captains of Riau from 1818 to 1828 contains the names Tan-Hoo, Tan-Tiauw-Goean and Tan- Ahooi69 – none sounding close to Tan Heng Kim. What can be surmised from these clues is that the benefactor of the temple Tan Heng Kim was the Heng Kim mentioned in the Teochew oral account (where his surname was apparently lost), who was simultaneously the enigmatic Captain China in Farquhar’s letters.

The reverence of Xuan Tian Shang Di is not without implication. This deity was not only revered by the Teochews in Singapore as Tua Lau Ia (大老爷), or “Chief Guardian Deity”,70 but was also the resident idol in Lao Pun Tao Kong Shrine (老本头公庙, built before 1824), the oldest Chinese temple in Bangkok’s Sampheng district, where the Teochew merchant community serving King Taksin had resettled after his rule ended in 1782.71

Worthy of note is that the same Xuan Tian Shang Di temple in Senggarang contained another artefact contributed in 1814 by a devotee with the partially-legible name Heng Hok [illegible character] (王福?),72 while government records in Singapore registered the sale of gambier plantations by three persons – Tan Ngun Ha, Tan Ah Loo and Heng Tooan – to Captain James Pearl in May 1822.73 The recurrences of the surnames Tan and Heng allow us to surmise that the first commercial enterprise in modern Singapore was formed by a Teochew partnership between members of a Tan clan based in Siam and a Heng clan from Dang Khoi.

Founding of Wak Hai Cheng Bio

Unlike a typical Chinese temple, Wak Hai Cheng Bio has not one, but two resident deities – Xuan Tian Shang Di and Mazu. The pair are housed in an edifice with adjoining prayer halls first built by Ngee Ann Kongsi between 1852 and 1855. While there is scant documentation of the temple’s early years, temple traditions hold that its site was once occupied by a lone attap hut sheltering a Mazu altar, before a Xuan Tian Shang Di shrine was added in 1826.74

This chronology of events dovetails with the Teochew oral account’s depiction of Wak Hai Cheng Bio being co-founded by Tan Heng Kim and Heng Hong Sung. Moreover, the account’s claim of the temple’s premises being used for the landing of travellers and goods is affirmed by the Malay reference to the Sua Kia Deng area as “Lorong Tambangan”, meaning “ferry lane”, as well as the recorded presence of the Master Attendant Captain William Flint’s residence and an “old fish market” nearby.75

As for when the Mazu shrine was built, it is conceivable that this happened only after end-June 1819, as inferred from Phua’s assertion in Teo-chews in Malaya that the Wak Hai Cheng Bio land was a grant from Temenggong Abdul Rahman, as well as Munshi Abdullah’s report that the Singapore River south bank had “nothing to be seen” before Chinese settlement.76 Further, considering the practice that every Teochew junk plying the route between China and Siam carried on board an idol of Mazu, which had to be invited into a temple or shrine at the destination port before goods were unloaded,77 this structure must have already stood along the Singapore River prior to Farquhar’s notice on the first junks from China and Siam in end-March 1820.

The estimation of dates is supported by the transaction record, dated 18 September 1822, of a house in Chinatown, whose location was reported to be “on the sea side of the Road leading past the old Chinese temple” [emphasis added].78

Oddly enough, differing information on the temple was presented in a write-up in Teo-chews in Malaya: Phua had penned instead that “Wak Hai Cheng Bio, as told, was at first an attap hut built by Lim Phueng (林泮), which till the third reign year of Qing Emperor Qianlong (i.e. 1738) was rebuilt many times…” In yet another part of the book, Phua characterised Lim Phueng as the founder of Ban See Soon Kongsi (万世顺公司) – reportedly an entity in Singapore set up to manage monetary gifts to Mazu from Teochew travellers from the Teochew region, Siam or Vietnam – and reported that this man was in Singapore in the early Qing period but was executed by a government official in China in 1738.79

Any possible connection between Lim Phueng and the first sojourners from Hai Ior was not raised.

Phua subsequently revised in his other publications the year of Wak Hai Cheng Bio’s foundation to the final year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign (1796).80 However, he did not make the change because he saw it was implausible that the Teochew people were active in Singapore some 80 years ahead of British arrival. He later reverted in a 1976 newspaper article to his original position that the Mazu attap shrine had been erected before 1738, but substituted Heng Hong Sung for Lim Phueng as the Ban See Soon Kongsi founder.81 Phua’s back and forth changes were seemingly compelled by his realisation that Lim Phueng, a merchant with a well-documented life, could not have been in Singapore in the 1730s. Famed for building a luxurious garden-mansion in the Teochew port town of Changlim (樟林) in 1799, Lim Phueng was put to death following a highprofile legal case in 1805.82

Despite uncertainty on his part, Phua did not relent on the existence of a Mazu shrine before the end of the 18th century. His insistence appears to be based on knowledge of oral traditions tied to Ban See Soon Kongsi. Similar to Phua’s writings, a working report issued by the Singapore Teo Chew Sai Ho Association in 1949 linked Wak Hai Cheng Bio’s foundation to Ban See Soon Kongsi. However it stated that the latter was formed at the beginning of Qing Emperor Qianlong’s reign in 1735, through the funding by Teochew red-head junk travellers in Singapore obligated to Mazu.83 The Teo Chew Sai Ho Association report made no reference to Lim Phueng.

In view of established knowledge on Singapore’s history, the possibility that a group of Teochew traders were active on the island before 1800 is remote. On the other hand, the notice in Tuhfat al Nafis about “Chinese from China” being brought into Riau around 1740, as well as markings of a “Chinese compound” there in British navigation charts between 1750 and 1762 (see Map 6), show that it was a place where Chinese traders congregated. While the 1779 Mazu deity tablet in Senggarang is the oldest-known physical proof of Teochew presence in Riau, Scottish sea captain Alexander Hamilton’s observation that about 1,000 Chinese families were settled in the towns of Johor at the beginning of the century supports the likelihood that some Teochew merchants might have been active there as early as the 1730s.84

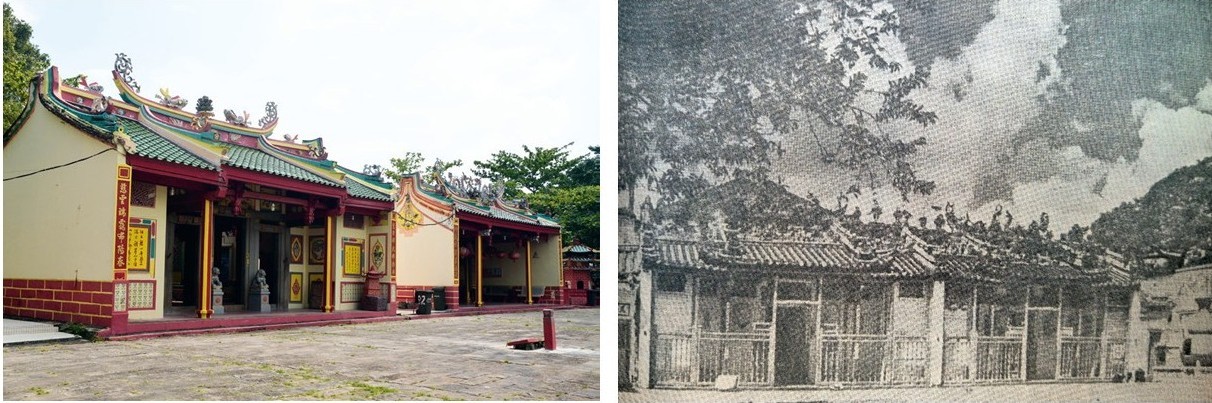

Accordingly, it is not an unreasonable conjecture that the oral traditions speak of two separate Mazu attap shrines. One being Wak Hai Cheng Bio’s forerunner that Tan Heng Kim and Heng Hong Sung set up by the Singapore River circa 1819 as reported by the Teochew oral account, and the other erected in the 1730s by Ban See Soon Kongsi that must have stood in Riau. An uncanny resemblance between Wak Hai Cheng Bio’s façade and the front view of Senggarang’s Mazu-Xuan Tian Shang Di twin temples (see Image 2) serves as a strong reminder that the Teochews on either side of the Singapore Straits were in fact two faces of one single community.

(Right) Wak Hai Cheng Bio circa 1958 with Fort Canning Hill in the background. All rights reserved. Pan Xingnong 潘醒农, 新加坡指南 [A guide to Singapore], 6th ed. 新加坡: 南岛出版社, 1958.

Nearly every historical writing and material evidence originating from the Malays, Chinese, British or Dutch concur that until 1819 Riau fulfilled the role of the much-needed entrepôt on the Singapore Straits. The intertwined traditions of Wak Hai Cheng Bio and the Senggarang temples call attention to the need to comprehend modern Singapore’s sudden emergence within the context of preceding developments in its surroundings, especially in Riau. An important point in relation to this is the oft-overlooked fact that Raffles himself was bound for Riau to set up an EI C station when he set sail from Calcutta on 7 December 1818, and only re-directed his course to Singapore after receiving news from Farquhar in Penang that the principal port of Johor had fallen under Dutch control.85

A Final Question

By November 1821, Singapore was reported to have had a “regularly built Chinese town” on the south bank of the Singapore River, while “plantations of gambier, pepper and other spices [had] already [made] their appearance in many parts”.86 Corroborations of its nearly every detail by other historical sources confirm the Teochew oral account to be from the voices of the Chinese behind these various developments.

Yet, one question remains: What made the Teochew gambier planters move to Singapore before the British came, especially if they knew the Malays there had previously slain their kinsmen?

The background of these Teochews as “sojourners recruited from Siam” suggests that they did not come to Singapore on their own initiative. The identity of the person who arranged for their migration is given away by a clause in the June 1819 Arrangement Made for the Singapore Government: “[T]he gardens and plantations that now are, or may hereafter be made” to be placed “at the disposal of the Tumungong, as heretofore”.87 Crucially, Temenggong Abdul Rahman was also documented to have provided for the cost and expenses of gambier plantations opened at Mount Stamford (now Pearl’s Hill) prior to the arrival of the British and “in some instances” advanced money to Teochew cultivators with the understanding that he would be repaid in the form of gambier or other produce.88 An impression Farquhar got from the Captain China – “one of the principal persons concerned” – was that the temenggong’s interests in these plantations were represented by his brother-in-law named Baba Ketchil, which adds more weight to the importance of these arrangements.89

Raffles’ characterisation of Singapore’s inhabitants as “new settlers” in his 8 January 1819 letter to Hastings implied that the Teochews only arrived on the island towards the end of 1818. The timing exposes a relationship to another key event, which was the conclusion of a treaty on 28 November 1818 by which Raja Jaafar permitted the Dutch to re-occupy Riau.

Besides Tengku Long, Temenggong Abdul Rahman was said to be the most vocal in opposing this agreement.90 This is hardly surprising as he professed to be an exile in Singapore,91 apparently as an outcome of Raja Jaafar’s political coup. More pertinently, the “head of the pirates” was manifestly the target of various articles in the Johor-Dutch pact, which obliged the Sultan of Johor to eradicate piracy and even grant the Dutch a host of powers to ensure this outcome.92

Inexplicably, it was the temenggong who ratified this treaty by affixing his seal on it, after the incumbent sultan (Tengku Long’s younger brother) refused to be involved. A plausible explanation for this situation is that Raja Jaafar had struck a bargain with Temenggong Abdul Rahman, permitting him to commence gambier planting in Singapore in return for rubberstamping his own deal with Melaka.

Interestingly, the diary of Captain John Crawford recorded that shortly after Raffles landed in Singapore, his request to disembark his soldiers and plant the British flag was acceded to by the temenggong with the exclamation that “nothing could give them greater happiness than to be in alliance with the English”.93 Only after this did the two leaders seal their first agreement, by which the EI C was committed to not only pay the Johor minister 3,000 Spanish dollars a year, but also to protect him. To this end, there seems little question to the Malay chief’s intention for rebellion against the powers in Riau. From his perspective, Raffles’ unexpected appearance with generous offers of money and military support could not have been more timely and helpful.

Conclusion

Temenggong Abdul Rahman’s agenda was not military, but trade through the creation of a rival port in Singapore. His negotiation in the 6 February 1819 treaty for “a moiety or full half of all the amount collected from Native Vessels” amply hints at this.94

This leaves room to ponder if the commercial value of gambier, as well as Raffles’ excited anticipation of Singapore’s access to “rice, salt, and other necessaries” from Siam (a country the British had no official trade with since an English community was massacred in Mergui in 1687), might not be signs that the temenggong already had an understanding with Tan Heng Kim to start a trading centre in Singapore before Raffles’ arrival.

By persistently insisting in his writings that he arrived at “an insignificant fishing village” in January 1819 and alluding to be responsible for the immediate influx of Chinese migrants, Raffles managed to whitewash the roles of Temenggong Abdul Rahman and his Teochew partners behind Singapore’s much-vaunted rise as a centre of commerce, while convincing others that the achievement was entirely his own.

However, an old Teochew oral account, validated by a body of evidence from multiple sources – including the earliest British reports about Singapore by Raffles, no less – now reveals that it was the coming together of many, and not just the brilliance of one man, that sparked the Singapore miracle.

Acknowledgments

I thank Dr Loh Kah Seng for reviewing this research paper and Mr Terence Tan for his input on the translations of relevant Chinese texts. I am also grateful to Ms Goh Yu Mei and other staff members at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library for their gracious assistance and constant thoughtfulness in supporting my research.

Jason Heng graduated in June 2013 from Shantou University in Guangdong, China, with a Master of Arts (Journalism). His previous research examined social media and how it supported the emergence of disparate “globalised villages” built on the collective consciousness of its members. He is currently the director of operations (Singapore and Southeast Asia) of a specialist risk mitigation consulting company.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abdullah Abdul Kadir. The Hikayat Abdullah: The Autobiography of Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, 1797–1854: An Annotated Translation, trans. A. H. Hill. Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1985. (Original work published 1969) (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.51032 ABD)

Bartley, W. “Population of Singapore in 1819,” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 11, no. 2 (December 1933): 177. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Bastin, John. The Founding of Singapore 1819. Singapore: National Library Board, 2012. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5703 BAS)

—. Raffles and Hastings: Private Exchanges Behind the Founding of Singapore. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2014. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5703 BAS-[HIS])

Buckley, Charles Burton. An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore. Vol. 1. Singapore: Fraser & Neave, 1902. (From National Library Online)

“Chaozhou: Taiguo chuan wang chenwansheng zhai di” 潮州: 泰国船王陈万胜宅第 [Chaozhou: mansion of Thailand shipping king Tan Buan Seng], 16 November 2013, 潮州热线 [CZOnline], accessed 8 January 2017, http://cztour.czonline.net/chaozhoulvyou/chaozhoufengjing/2013-11-16/57542.html.

Chaoshan shuzhai yi shi 潮汕书斋轶事 [The Teochew Study Houses Anecdotes], 9 November 2007, 潮人在线 [Chaoren.com], accessed 13 November 2016.

“Chaoshan wang shi” 潮汕王氏 [Heng Clan in the Teochew region], 汕头大学图书馆-潮汕特藏网 [Shantou University Library – Teochew Special Collection website], accessed 14 December 2016.

Chen, Bietong 陈别同, ed. Xin jia po chao zhou lian qiao ju le bu te kan 新加坡潮州联侨俱乐部特刊 [Singapore Teo Chew Lian Kheow club special publication]. 新加坡: 潮州联侨俱乐部, 1949. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS q369.25957 SIN)

Chen, Chunsheng 陈春声. Xiangcun de gushi yu guojia de lishi – yi zhang lin wei li jian lun chuantong xiangcun shehui yanjiu de fangfa wenti 乡村的故事与国家的历史 – 以樟林为例兼论传统乡村社会研究的方法问题 [Stories from the villages and history of the country – a discussion on methodological challenges in researching traditional village societies using Changlim as an example], Zhongguo nongcun yanjiu 中国农村研究 [Rural Studies of China]. 中国: 商务印书馆, 2003.

Chen, Jingying and Li Yang 陈静莹 and 李扬. “Mazu ‘hai zhi lu’ shouhu shen,” 妈祖 ‘海之路’ 守护神 [Mazu, protectress deity on the ‘Maritime Silk Road’], Shantou Ribao 汕头日报, 14 August 2014, 10.

Chen, Xiaoche 陈孝彻. “Danshui gang: Wei hongtou chuan jingshen tian zuozheng” 淡水缸: 为红头船精神添佐证 [A Freshwater Vat: A Testament to the Red Head Junk Spirit], Shantou Tequ Wanbao 汕头特区晚报, 21 September 2014, 5, https://ms.dcsdcs.com/7498.html.

Zhuang, Qinyong 庄钦永. Xin xia huaren shi xin kao 新呷华人史新考 [History of the Chinese in Singapore & Malacca: some notes]. 新加坡: 南洋学会, 1990. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS 305.895105957 CDK)

Crawfurd, John. A Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands and Adjacent Countries. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1856. (From National Library Online)

—. Journal of an Embassy From the Governor-General of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China, vol. 2, 2nd ed. London: Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, 1830. (From National Library Online)

Eastern Settlements, The Bengal and Agra Annual Guide and Gazetteer. Vol. 2. Calcutta: W. Rushton and Company, 1842, 283–95.

Farquhar, William. “The Establishment of Singapore,” Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British and Foreign India, China and Australasia 2 (May–August 1830): 140–42.

Franke, Wolfgang, ed., Chinese Epigraphic Materials in Indonesia. Vol. 1. Singapore: South Seas Society, 1988. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.8 FRA)

Franke, Wolfgang and Pornpan Juntaronanont, eds., Chinese Epigraphic Materials in Thailand. Taipei: Xinwenfeng Chuban Gongsi, 1998, 13.

Gützlaff, Karl Friedrich August. The Journal of Two Voyages Along the Coast of China, in 1831, & 1832. New York: John P. Haven, 1833. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 915.10433 GUT)

Hamilton, Alexander. A New Account of the East Indies. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: John Mosman, 1727. (From National Library Online)

Huang, Yao 黄尧, ed., Xing ma huaren zhi 星马华人志 [The history of the Chinese in Malaysia and Singapore]. 香港: 明鉴出版社, 1967. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 325.25109595 HY-[HYT])

Kwa, Chong Guan, Derek Heng and Tan Tai Yong. Singapore, a 700-Year History: From Early Emporium to World City. Singapore: National Archives of Singapore, 2009. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5703 KWA-[HIS])

Lao Pun Tao Kong Shrine. “About the Shrine.” Accessed 5 February 2014, http://laopuntaokong.org/history/index_en.asp

Li, Zhixian 李志贤, ed., Hai wai Chao ren de yi min jing yan 海外潮人的移民经验 [The Migration Experience of the Overseas Teochew Community]. 新加坡: 新加坡潮州八邑会馆: 八方文化企业, 2003. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RCO 305.8951 INT)

Lianhe Zaobao. Xie Yanyan 谢燕燕, “Xuanyang miaoyu wenhua yu lishi neihan –rang bainian yue hai qing miao xun hui xiri guanghui” 宣扬庙宇文化与历史内涵 –让百年粤海清庙寻回昔日光辉 [Promote the Temple Culture and its Historical Connotations – Let century-old Wak Hai Cheng Bio find back its Glory]. 14 June 2010, 9 (From NewspaperSG)

Lin, Ji 林济. “Jindai dongnanya chao shang yu shan xiang xian le guoji maoyi quan di yi jie zaoqi de dongnanya chaozhou yimín” 近代东南亚潮商与汕香暹叻国际贸易圈 第一节 早期的东南亚潮州移民 [Modern Teochew Merchants and Their International Business Circles in Swatow, Hong Kong, Thailand and Singapore – Part 1 – The Early Teochew Migrants to Southeast Asia], 2 February 2010, World Chaoshang, accessed 15 March 2017

Lin Xiao 林孝 et al., Shi le gu ji 石叻古迹 [Historical Monuments in Selat]. 新加坡: 南洋学会, 1975. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RSING 959.57 SLK-[HIS])

Makepeace, Walter, Gilbert E. Brooke and Ronald S. J. Braddell, eds., One Hundred Years of Singapore. Vol. 1. London: John Murray, 1921. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.51 MAK-[RFL])

Maxwell, W. E. Notes and Queries. No. 1. Singapore: Printed at the Government Printing Office, 1885. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 959.5 ROY)

Miller, Eric H. “Letters of Col Nahuijs.” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 19, no. 2 (October 1941): 169–209. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Nanyang Sian Pau. Pan Xingnong 潘醒农, “Xinjiapo huaren gu shen miao yue hai qing miao” 新加坡华人古神庙粤海清庙 [Wak Hai Cheng Bio, a historical temple of the Singapore Chinese]. 26 July 1976, 14. (From NewspaperSG)

Netscher, E. “Beschrijving Van Een Gedeelte Der Residentie Riouw.” Tijdschrift Voor Indische Taal-, Land-, En Volkenkunde, 2 (1854): 108–270. Edited by P. Bleeker, E. Munnich and E. Netscher.

—. De Nederlanders in Djohor En Siak. Batavia: Bruining & Wijt, 1870. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 959.52 NET)

Newbold, Thomas John. Political and Statistical Account of the British Settlements in the Straits of Malacca, Viz. Pinang, Malacca, and Singapore. Vol. 1. London: John Murray, 1839. (From National Library Online)

Ng, Ching Keong. The Chinese in Riau: A Community on an Unstable and Restrictive Frontier. (Research Project Series, no. 2). Singapore: Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences, College of Graduate Studies, Nanyang University, 1976. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 301.4519510598 NG)

“Notices of Singapore.” Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia 9 (January–March 1855): 53–65, 444–82. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 950.05 JOU, microfilm NL25797)

National University Singapore Libraries, 潘醒农 (Phua Chay Long, 1904–1987), 25 September 2008.

Pan, Xingnong 潘醒农, ed., Nanyang ge shu di ming jie ming lu 南洋各属地名街名录 [Directory of towns and streets in malay archipelago]. 新加坡: 南岛出版社, 1939. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RRARE 915.9003 DIR)

—. Malaiya chao qiao tong jian 马来亚潮侨通鉴 [Teo-chews in Malaya]. 新加坡: 南岛出版社, 1950. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS 305.895105951 PXN)

—. Dongnanya mingsheng 东南亚名胜 [Celebrated places in S. E. Asia]. 新加坡: 南岛出版社, 1954. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RDTYK 959 PXN)

—. Xinjiapo zhi nan 新加坡指南 [A guide to Singapore]. 6th ed. 新加坡: 南岛出版社, 1958. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS 959.57 PXN)

—. Xing Ma ming sheng 星马名胜 [Celebrated places in Singapore-Malaya]. 新加坡: 南岛出版社, 1961. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS 959.5 PHN)

Raffles, Sophia. Memoir of the Life and Public Services of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles. London: John Murray, 1830. (From National Library Online)

Raffles, Thomas Stamford. Substance of a Memoir on the Administration of the Eastern Islands. n.p.: n.p., 1824. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 325.31 RAF)

Ali al-Haji Riau (Raja). The Precious Gift (Tuhfat al-Nafis). Translated by Virginia Matheson and Barbara Watson Andaya. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1982, 125–6. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.5142 ALI)

Siah, U Chin. “General Sketch of the Numbers, Tribes and Avocations of the Chinese in Singapore.” Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia 2 (1848): 283–90 [From National Library Online)

Singapore Teochew Xihe Association 新加坡潮州西河公会. Chaozhou Xihe gong hui: Zhonghua Minguo 38 nian 1 yue zhi 6 yue fen hui wu bao gao shu 新加坡潮州西河公会: 中华民国卅八年一月至六月份会务报告书 [Singapore Teochew Sai Ho Association: Working report for January to June 1949]. 新加坡: 新加坡潮州西河公会, 1949. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS 369.25957 XJP)

Solomon, Eli. Farquhar’s Life in the Far East: A Chronology. Singapore: Singapore Resource Library, National Library Board, 1996. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.503 SOL)

Song, Ong Siang. One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore. Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1984. (Original work published 1902). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.57 SON-[HIS])

Straits Settlements Records, L6: Singapore: Letters to Bencoolen. (From National Archives of Singapore microfilm NL56)

—. L10: Singapore: Letters to Bencoolen. (From National Archives of Singapore microfilm NL57)

—. L11: Letters to and from Raffles. (From National Archives of Singapore microfilm NL57)

—. L13: Raffles: Letters from Singapore. (From National Archives of Singapore microfilm NL58)

—. L17: Letters to Singapore (Farquhar). (From National Archives of Singapore microfilm NL58)

Straits Times. “How Singapore was Founded.” 18 October 1937, 10. (From NewspaperSG)

The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British India and its Dependencies (January–June 1820): 9.

The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British and Foreign India, China, and Australia 14 (July–December 1822): 14. (microfilm NL18125)

大清历朝实录 [The veritable records of Qing dynasty], 卷990 [scroll number 990]: 乾隆四十年九月乙卯 [Qianlong 40.9.7].

Turnbull, C. M. A History of Modern Singapore, 1819–2005. Singapore: NUS Press, 2009. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING959.57 TUR-[HIS])

Viraphol, Sarasin and Wutdichai Moolsilpa, eds., Tribute and Profit: Sino-Siamese Trade, 1652–1853. Chiang Mai, Thailand: Silkworm Books, 2014. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 382.09510593 SAR). Original work published 1977.

Wak Hai Cheng Bio (Yueh Hai Ching Temple).” Ngee Ann Kongsi, accessed 24 February 2017, https://thengeeannkongsi.com.sg/en/community-services/wak-hai-cheng-bio-yueh-hai-ching-temple/.

Wurtzburg, C. E. Raffles of the Eastern Isles. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1954. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.570210924 WUR)

Xu, Wurong 许武荣. Malaiya Chao qiao yin xiang ji 马来亚潮侨印象记 [The impression of teo-chews in Malaya]. 新加坡 : 南洋书局, 1951. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RDTYS 325.25109595 HWY)

Yang, Bingnan 杨炳南. Hai lu ji qi ta san zhong 海录及其他三种 [Records of the Sea and three other writings]. 上海 : 商务印书馆, 1936. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RDTYS 959 YPN)

粤海清庙 [Yue Hai Ching Temple]. Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan, accessed 8 March 2017, http://teochew.sg/八邑相关社团/粤海清庙/.

Zhang, Jiaqing 张家庆. “Chao ren yimin haiwai ji lue” 潮人移民海外纪略 [Accounts of the teochew people migrating overseas], Chaozhou Daily 潮州日报, 30 July 2015, 6.

Zhang, Xiaoshan 张晓山. Xin chaoshan zidian 新潮汕字典 [The new teochew dictionary]. 广州市: 广东人民出版社, 2015. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese R 495.1795127 XCS-[DIC])

Zhou, Hanren 周汉人, ed., Nanyang Chao qiao ren wu zhi yu Chaozhou ge xian yan ge shi 南洋潮侨人物志与潮州各县沿革史 [Biographies of overseas Teochew leaders with history of Teochew districts]. 新加坡: 中华出版社, 1958. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS 920.059 CHJ)

Appendix I

1 Names of Teochew persons and place names without commonly used romanisation are transcribed from Chinese according to transliterations found on the website 潮州•母语 (Teochew Mogher): www.mogher.com.

2 Literally “gateway of the straits”, with Sek Lak being a transliteration of selat, meaning “straits” in Malay. This is a colloquial Chinese name for Telok Blangah Road. See Pan Xingnong 潘醒农, ed., Nanyang ge shu di ming jie ming lu 南洋各属地名街名录 [Directory of towns and streets in malay archipelago] (新加坡: 南岛出版社, 1939), 98. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RRARE 915.9003 DIR)

3 In Chinese: Haiyang. A county in the historical Teochew prefecture in China, now Teo Ann (潮安, Chao’an) district in the Chaozhou prefectural-city.

4 Wak Hai Cheng Bio is currently located at 30B Phillip Street.

5 This is a historical name of the Teochew prefecture from the 5th and 6th centuries. Ngee Ann Kun was the predecessor of Ngee Ann Kongsi that was formed in 1845.

6 In Teochew: Ang Thau Tsung. Based on an edict issued by Qing Emperor Yongzheng in 1723, junks from various provinces in China had to have their bows painted in different colours for custom inspection and taxation purposes. Vessels from Guangdong, which the Teochew prefecture was part of, were red and those from Fujian green. As many red-head junks were built and operated by the Teochews in Siam, this category of junks became synonymous with the community.

7 Literally means “royal hill”. This was a colloquial Chinese name of Fort Canning Hill. See Ronald S. J. Braddell, R. S. J. (1991). “The Merry Past,” in One Hundred Years of Singapore, ed. Walter Makepeace, Gilbert E. Brooke and Ronald S. J. Braddell, vol. 1 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1991), 470. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.57 ONE-[HIS])

8 Pan Xingnong 潘醒农, ed., Malaiya chao qiao tong jian 马来亚潮侨通鉴 [Teo-chews in Malaya] (新加坡: 南岛出版社, 1950), 29. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS 305.895105951 PXN)

9 Pan, Malaiya chao qiao tong jian, 40.

NOTES

-

Letter from T. S. Raffles to Duchess of Somerset dated 11 June 1819, as cited in John Bastin, Raffles and Hastings: Private Exchanges Behind the Founding of Singapore (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2014), 88–89. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5703 BAS-[HIS]) ↩

-

Letter from T. S. Raffles to Marquess of Lansdowne dated 15 April 1820, as cited in John Bastin, Raffles and Hastings: Private Exchanges Behind the Founding of Singapore (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2014), 147–52 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5703 BAS-[HIS]); Letter from T. S. Raffles to Duke of Somerset dated 20 August 1820, as cited in Sophia Raffles, Memoir of the Life and Public Services of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (London: John Murray, 1830), 464–68. (From National Library Online). The population numbers cited by Raffles are highly questionable. Raffles was informed by Singapore’s Resident William Farquhar in May 1820 of a census finding that the island had no more than 4,727 residents with 506 houses, of whom 1,159 were Chinese. See Eli Solomon, Farquhar’s Life in the Far East: A Chronology (Singapore: Singapore Resource Library, National Library Board, 1996), 32 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.503 SOL); Walter Makepeace, Gilbert E. Brooke and Ronald S. J. Braddell, eds., One Hundred Years of Singapore, vol. 1 (London: John Murray, 1921), 344. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.51 MAK-[RFL]). Furthermore official census figures from subsequent years show that Singapore’s total population surpassed the 10,000 mark only at the end of 1823 and the Chinese only overtook the Malays as the largest community in 1827. See Eastern Settlements, The Bengal and Agra Annual Guide and Gazetteer, vol. 2. (Calcutta: W. Rushton and Company, 1842), 287. ↩

-

Letter from T. S. Raffles to The Marquess of Hastings KG dated 8 January 1819, as cited John Bastin, Raffles and Hastings: Private Exchanges Behind the Founding of Singapore (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2014), 32–35. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5703 BAS-[HIS]) ↩

-

Thomas Stamford Raffles, Substance of a Memoir on the Administration of the Eastern Islands (n.p.: n.p., 1824), 12. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 325.31 RAF) ↩

-

For the articles of these two treaties, see Charles Burton Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, vol. 1. (Singapore: Fraser & Neave, 1902), 36, 28–40. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

Despatch from T. S. Raffles to J. Adam, Esq. dated 13 February 1819, as cited in John Bastin, Raffles and Hastings: Private Exchanges Behind the Founding of Singapore (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2014), 52–70. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5703 BAS-[HIS]) ↩

-

Letter from “Carnegie” to unknown dated 2 July 1819, as cited in Sophia Raffles, Memoir of the Life and Public Services of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, 402. Rhio, or Riau, refers to Bintan island. ↩

-

William Farquhar, “The Establishment of Singapore,” Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British and Foreign India, China and Australasia 2 (May–August 1830): 140. ↩

-

“How Singapore was Founded,” Straits Times, 18 October 1937, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

John Bastin, Raffles and Hastings: Private Exchanges Behind the Founding of Singapore (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2014), 51. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5703 BAS-[HIS]) ↩

-

Taking the cue from T. J. Newbold, many historians have expressed in their works that Singapore had 20 to 30 Chinese in January 1819. However, Newbold’s estimate has been pointed out by W. Bartley to be without authority and questionable. See Thomas John Newbold, Political and Statistical Account of the British Settlements in the Straits of Malacca, Viz. Pinang, Malacca, and Singapore, vol. 1 (London: John Murray, 1839), 279 (From National Library Online); Song Ong Siang, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1984), 6. (Original work published 1902). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.57 SON-[HIS]); C. M. Turnbull, A History of Modern Singapore, 1819–2005 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2009), 25 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING959.57 TUR-[HIS]); Kwa Chong Guan, Derek Heng and Tan Tai Yong, Singapore, a 700-Year History: From Early Emporium to World City (Singapore: National Archives of Singapore, 2009), 111 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5703 KWA-[HIS]); W. Bartley, “Population of Singapore in 1819,” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 11, no. 2 (December 1933): 177. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Kwa, Heng and Tan, Singapore, a 700-Year History, 1. ↩

-

Siah U Chin, “General Sketch of the Numbers, Tribes and Avocations of the Chinese in Singapore,” Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia 2 (1848): 283–90 [From National Library Online) ↩

-

These publications include Chen Bietong 陈别同, ed., Xin jia po chao zhou lian qiao ju le bu te kan 新加坡潮州联侨俱乐部特刊 [Singapore Teo Chew Lian Kheow club special publication] (新加坡: 潮州联侨俱乐部, 1949) (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS q369.25957 SIN); Singapore Teochew Xihe Association 新加坡潮州西河公会, Chaozhou Xihe gong hui: Zhonghua Minguo 38 nian 1 yue zhi 6 yue fen hui wu bao gao shu 新加坡潮州西河公会: 中华民国卅八年一月至六月份会务报告书 [Singapore Teochew Sai Ho Association: Working report for January to June 1949] (新加坡: 新加坡潮州西河公会, 1949) (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS 369.25957 XJP); Xu Wurong 许武荣, Malaiya Chao qiao yin xiang ji 马来亚潮侨印象记 [The impression of teo-chews in Malaya] (新加坡 : 南洋书局, 1951). (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RDTYS 325.25109595 HWY) ↩

-

Variant spellings: Phua Chay Leong and Phua Chay Long. Names of Teochew persons and places without commonly used romanisation are transcribed from Chinese according to transliterations found on the website 潮州•母语 (Teochew Mogher): www.mogher.com. ↩

-

Zhou Hanren 周汉人, ed., Nanyang Chao qiao ren wu zhi yu Chaozhou ge xian yan ge shi 南洋潮侨人物志与潮州各县沿革史 [Biographies of overseas Teochew leaders with history of Teochew districts] (新加坡: 中华出版社, 1958), AA24 (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS 920.059 CHJ); National University Singapore Libraries, 潘醒农 (Phua Chay Long, 1904–1987), 25 September 2008. ↩

-

Literally “gateway of the straits”, with Sek Lak being a transliteration of selat, meaning “straits” in Malay. This is a colloquial Chinese name for Telok Blangah Road. See Pan Xingnong 潘醒农, ed., Nanyang ge shu di ming jie ming lu 南洋各属地名街名录 [Directory of towns and streets in malay archipelago] (新加坡: 南岛出版社, 1939), 98. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RRARE 915.9003 DIR) ↩

-

County in the historical Teochew prefecture in China, now Teo Ann (潮安, in Mandarin Chao’an) district in Chaozhou prefectural-city. ↩

-

Wak Hai Cheng Bio, also known as Yueh Hai Ching Temple, is located at 30B Phillip Street today. ↩

-

This is a historical name of the Teochew prefecture from the 5th and 6th centuries. Ngee Ann Kun was the predecessor of Ngee Ann Kongsi that was formed in 1845. ↩

-

红头船. In Teochew: Ang Thau Tsung. Based on an edict issued by Qing Emperor Yongzheng in 1723, junks from various provinces in China had to have their bows painted in different colours for customs inspection and taxation purposes. Vessels from Guangdong, of which the Teochew prefecture was a part, were assigned red and those from Fujian, green. As many red-head junks were built and operated by the Teochews in Siam, this category of junks became synonymous with the community. ↩

-

Literally means “royal hill”. This was a colloquial Chinese name of Fort Canning Hill. See Ronald S. J. Braddell, “The Good Old Days,” in Makepeace, Brooke and Braddell, One Hundred Years of Singapore, vol. 1, 470. ↩

-

Pan Xingnong 潘醒农, ed., Malaiya chao qiao tong jian 马来亚潮侨通鉴 [Teo-chews in Malaya] (新加坡: 南岛出版社, 1950), 29. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS 305.895105951 PXN) ↩

-

Pan, Malaiya chao qiao tong jian, 40. ↩

-

The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British India and its Dependencies (January–June 1820): 9, 93. ↩

-

John Crawfurd, A Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands and Adjacent Countries (London: Bradbury & Evans, 1856), 402 (From National Library Online); Abdullah Abdul Kadir, The Hikayat Abdullah: The Autobiography of Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, 1797–1854: An Annotated Translation, trans. A. H. Hill (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1985), 176–77. (Original work published 1969) (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.51032 ABD); and Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, vol. 1, 104. ↩

-

Pan, Malaiya chao qiao tong jian, 351. ↩

-

Zhou, Nanyang Chao qiao ren wu zhi yu Chaozhou ge xian yan ge shi, AA24. ↩

-

These publications include Xu, Malaiya Chao qiao yin xiang ji; Huang Yao 黄尧, ed., Xing ma huaren zhi 星马华人志 [The history of the Chinese in Malaysia and Singapore] (2003; repr., 香港: 明鉴出版社, 1967) (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 325.25109595 HY-[HYT]; Chinese RSEA q959.5004951 HY); Lin Xiao 林孝, et al., Shi le gu ji 石叻古迹 [Historical Monuments in Selat] (新加坡: 南洋学会, 1975) (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RSING 959.57 SLK-[HIS]); Li Zhixian 李志贤, ed., Hai wai Chao ren de yi min jing yan 海外潮人的移民经验 [The Migration Experience of the Overseas Teochew Community] (新加坡: 新加坡潮州八邑会馆: 八方文化企业, 2003). (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RCO 305.8951 INT) ↩

-

Examples of these references include: Xie Yanyan 谢燕燕, “Xuanyang miaoyu wenhua yu lishi neihan –rang bainian yue hai qing miao xun hui xiri guanghui” 宣扬庙宇文化与历史内涵 –让百年粤海清庙寻回昔日光辉 [Promote the Temple Culture and its Historical Connotations – Let century-old Wak Hai Cheng Bio find back its Glory], Lianhe Zaobao 联合早报, 14 June 2010, 9 (From NewspaperSG); Zhang Jiaqing 张家庆, “Chao ren yimin haiwai ji lue” 潮人移民海外纪略 [Accounts of the teochew people migrating overseas], Chaozhou Daily 潮州日报, 30 July 2015, 6; Lin Ji 林济, “Jindai dongnanya chao shang yu shan xiang xian le guoji maoyi quan di yi jie zaoqi de dongnanya chaozhou yimín” 近代东南亚潮商与汕香暹叻国际贸易圈 第一节 早期的东南亚潮州移民 [Modern Teochew Merchants and Their International Business Circles in Swatow, Hong Kong, Thailand and Singapore – Part 1 – The Early Teochew Migrants to Southeast Asia], 2 February 2010, World Chaoshang, accessed 15 March 2017; “Yue hai qing miao” 粤海清庙 [Yue Hai Ching Temple], Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan, accessed 8 March 2017, http://teochew.sg/八邑相关社团/粤海清庙/. ↩

-

Eric H. Miller, “Letters of Col Nahuijs,” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 19, no. 2 (October 1941): 192–93. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Letter from W. Farquhar, Resident, to Lt. L. N. Hull dated 28 December 1822; and Letter from W. Farquhar, Resident, to Lt. L. N. Hull, Secretary to the Lieutenant Governor dated 23 December 1822, as cited in Bartley, “Population of Singapore in 1819,” 177. ↩

-

Farquhar to Hull, 5 November 1822; Straits Settements Records, L11: Letters to and from Raffles, December 1822, 111. (From National Archives of Singapore microfilm NL57). The Captain China post was created on Raffles’ instructions to place foreign settlers “under the immediate superintendence of chiefs of their own tribes” for the purpose of maintaining order. See Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, vol. 1, 56–57. ↩

-

Hull to Farquhar, 4 February 1823, Straits Settlements Records, L17: Letters to Singapore (Farquhar), no. 60 (From National Archives of Singapore microfilm NL58); Farquar to Hull, 4 February 1823, Straits Settlements Records, L13: Raffles: Letters from Singapore, no. 72. (From National Archives of Singapore microfilm NL58) ↩

-

Farquhar to Hull, 21 January 1823, Straits Settlements Records, L13: Raffles: Letters from Singapore, no. 30. (From National Archives of Singapore microfilm NL58) ↩

-

Siah, “General Sketch of the Numbers, Tribes and Avocations of the Chinese in Singapore,” 283–90. ↩

-

Ali al-Haji Riau (Raja), The Precious Gift (Tuhfat al-Nafis), trans. Virginia Matheson and Barbara Watson Andaya (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1982), 125–6. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.5142 ALI) ↩

-

Also spelt “Kantonners” and “Emoeijers”. E. Netscher, De Nederlanders in Djohor En Siak (Batavia: Bruining & Wijt, 1870), 200. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 959.52 NET) ↩

-

E. Netscher, “Beschrijving Van Een Gedeelte Der Residentie Riouw,” in Tijdschrift Voor Indische Taal-, Land-, En Volkenkunde, 2 (1854): 160, ed. P. Bleeker, E. Munnich and E. Netscher. ↩

-

Xu, Malaiya Chao qiao yin xiang ji, 28. ↩

-

Ng Ching Keong, The Chinese in Riau: A Community on an Unstable and Restrictive Frontier, Research Project Series, no. 2 (Singapore: Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences, College of Graduate Studies, Nanyang University, 1976), 14. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 301.4519510598 NG). Senggarang and Tanjung Pinang were reported to be otherwise known as “big bank” (大坡) and “small bank” (小坡). ↩

-

The Resident to Fort Malboro, 3 November 1819, Straits Settlements Records, L10: Singapore: Letters to Bencoolen, 195–96. (From National Archives of Singapore microfilm NL57) ↩

-

Letter from W, Farquhar to T. S. Raffles, dated 21 March 1820, as cited in Sophia Raffles, Memoir of the Life and Public Services of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, 443–45. Based on a report that the first Amoy junk only anchored at Singapore in February 1821, the three junks from China had to be red-head junks and most probably Teochew. See Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, vol. 1, 67. ↩

-

Letter from Supreme Governor to Farquhar, dated 11 January 1820, as cited in “Notices of Singapore,” Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia 9 (January–March 1855): 444. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 950.05 JOU, microfilm NL25797) ↩

-

John Crawfurd, Journal of an Embassy From the Governor-General of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China, vol. 2, 2nd ed. (London: Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, 1830), 160–6, 177. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

Sarasin Viraphol and Wutdichai Moolsilpa, eds., Tribute and Profit: Sino-Siamese Trade, 1652–1853 (Chiang Mai, Thailand: Silkworm Books, 2014), 176. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 382.09510593 SAR). Original work published 1977. ↩

-

“Chaozhou: Taiguo chuan wang chenwansheng zhai di” 潮州: 泰国船王陈万胜宅第 [Chaozhou: mansion of Thailand shipping king Tan Buan Seng], 16 November 2013, 潮州热线 [CZOnline], accessed 8 January 2017, http://cztour.czonline.net/chaozhoulvyou/chaozhoufengjing/2013-11-16/57542.html; Chen Xiaoche 陈孝彻, “Danshui gang: Wei hongtou chuan jingshen tian zuozheng” 淡水缸: 为红头船精神添佐证 [A Freshwater Vat: A Testament to the Red Head Junk Spirit], Shantou Tequ Wanbao 汕头特区晚报, 21 September 2014, 5, https://ms.dcsdcs.com/7498.html. ↩

-

大清历朝实录 [The veritable records of Qing dynasty], 卷990 [scroll number 990]: 乾隆四十年九月乙卯 [Qianlong 40.9.7]. ↩

-

Viraphol and Moolsilpa, Tribute and Profit: Sino-Siamese Trade, 1652–1853, 163. ↩

-

Ali al-Haji Riau (Raja), Precious Gift (Tuhfat al-Nafis), 239–40, 252. ↩

-

Wolfgang Franke, ed., Chinese Epigraphic Materials in Indonesia, vol. 1 (Singapore: South Seas Society, 1988), 354. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.8 FRA) ↩

-

Ali al-Haji Riau (Raja), The Precious Gift (Tuhfat al-Nafis), 332. ↩

-

Franke, Chinese Epigraphic Materials in Indonesia, vol. 1, 355. ↩

-

Netscher, “Beschrijving Van Een Gedeelte Der Residentie Riouw,” 159. ↩

-

Yang Bingnan 杨炳南, Hai lu ji qi ta san zhong 海录及其他三种 [Records of the Sea and three other writings] (上海 : 商务印书馆, 1936), 7. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RDTYS 959 YPN). (Original work published c. 1820). Interestingly, Singapore was popularly referred by its local Chinese until the mid 1900s as Sig Lag (石叻), which is the Teochew/Hokkien transliteration of selat. ↩

-

L11: Letters to and from Raffles, 5 November 1822, 111. ↩

-

For articles of this agreement, see Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, vol. 1, 58–59. ↩

-

Letter from W. Farquhar to T. S. Raffles dated 2 September 1819, as cited in C. E. Wurtzburg, Raffles of the Eastern Isles (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1954), 541. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.570210924 WUR) ↩

-

For an introduction of the Bute Map, see Lim Chen Sian, “The Earliest Landward Map of Singapore Preserved in the Bute Collection at Mount Stuart, Isle of Bute, Scotland,” in John Bastin, The Founding of Singapore 1819 (Singapore: National Library Board, 2012), 199–219. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5703 BAS) ↩

-

Letter from W. Farquhar to T. S. Raffles dated 31 March 1820, as cited in Raffles, Memoir of the Life and Public Services of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, 433–4. ↩

-

Abdullah Abdul Kadir, The Hikayat Abdullah: The Autobiography of Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, 1797–1854, 145. ↩

-

Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, vol. 1, 75. ↩

-

Petition of Chinese Inhabitants residing in China Town to William Farquhar dated 4 December 1822, Straits Settlements Records, L6: Singapore: Letters to Bencoolen, 26. (From National Archives of Singapore microfilm NL56) ↩

-

Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, vol. 1, 75. ↩

-

“Chaoshan wang shi” 潮汕王氏 [Heng Clan in the Teochew region], 汕头大学图书馆-潮汕特藏网 [Shantou University Library – Teochew Special Collection website], accessed 14 December 2016. ↩

-

Chaoshan shuzhai yi shi 潮汕书斋轶事 [The Teochew Study Houses Anecdotes], 9 November 2007, 潮人在线 [Chaoren.com], accessed 13 November 2016. ↩

-

Franke, Chinese Epigraphic Materials in Indonesia, vol. 1, 358. ↩

-

Zhang Xiaoshan 张晓山, Xin chaoshan zidian 新潮汕字典 [The new teochew dictionary] (广州市: 广东人民出版社, 2015). (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese R 495.1795127 XCS-[DIC]) ↩

-

Netscher, “Beschrijving Van Een Gedeelte Der Residentie Riouw,” 159. ↩

-

Pan Xingnong 潘醒农, “Xinjiapo huaren gu shen miao yue hai qing miao” 新加坡华人古神庙粤海清庙 [Wak Hai Cheng Bio, a historical temple of the Singapore Chinese], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 26 July 1976, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Also known as Da-Bentougong miao (大本头公庙). “About the Shrine,” Lao Pun Tao Kong, accessed 5 February 2014, http://laopuntaokong.org/history/index_en.asp; Wolfgang Franke and Pornpan Juntaronanont, eds., Chinese Epigraphic Materials in Thailand (Taipei: Xinwenfeng Chuban Gongsi, 1998), 13. ↩

-

Franke, ed., Chinese Epigraphic Materials in Indonesia, vol. 1, 357. ↩

-

Acknowledgements of sale made before the Registrar of Land dated 10 May 1822 (by Tan Ngun Ha and Tan Ah Loo) and dated 13 May 1822 (for Heng Tooan) in Straits Settlements Records, L6: Singapore: Letters to Bencoolen, as cited in Bartley, “Population of Singapore in 1819,” 177. ↩

-

Pan, “Xinjiapo huaren gu shen miao yue hai qing miao”; Wak Hai Cheng Bio (Yueh Hai Ching Temple),” Ngee Ann Kongsi, accessed 24 February 2017, https://thengeeannkongsi.com.sg/en/community-services/wak-hai-cheng-bio-yueh-hai-ching-temple/. ↩

-

Abdullah Abdul Kadir, The Hikayat Abdullah: The Autobiography of Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, 1797–1854, 145; Farquhar to Bernard, 7 January 1823, Straits Settlements Records, L13: Raffles: Letters from Singapore, no. 11. (From National Archives of Singapore microfilm NL58) ↩

-

Abdullah Abdul Kadir, The Hikayat Abdullah: The Autobiography of Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, 1797–1854, 145. ↩

-

Karl Friedrich August Gützlaff, The Journal of Two Voyages Along the Coast of China, in 1831, & 1832 (New York: John P. Haven, 1833), 47–50 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 915.10433 GUT); Chen Jingying and Li Yang 陈静莹 and 李扬. [Chen, “Mazu ‘hai zhi lu’ shouhu shen,” 妈祖 ‘海之路’ 守护神 [Mazu, protectress deity on the ‘Maritime Silk Road’], Shantou Ribao 汕头日报, 14 August 2014, 10. ↩

-

Straits Settlements Records, L6: Singapore: Letters to Bencoolen, 17. ↩

-

Pan, Malaiya chao qiao tong jian, 351, 333–34. ↩

-

Pan Xingnong 潘醒农, Dongnanya mingsheng 东南亚名胜 [Celebrated places in S. E. Asia] (新加坡: 南岛出版社, 1954), 12 (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RDTYK 959 PXN); Pan Xingnong 潘醒农, Xinjiapo zhi nan 新加坡指南 [A guide to Singapore], 6th ed. (新加坡: 南岛出版社, 1958), 108 (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS 959.57 PXN); Pan Xingnong 潘醒农, Xing Ma ming sheng 星马名胜 [Celebrated places in Singapore-Malaya] (新加坡: 南岛出版社, 1961), 41. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS 959.5 PHN) ↩

-

Chen Chunsheng 陈春声, Xiangcun de gushi yu guojia de lishi – yi zhang lin wei li jian lun chuantong xiangcun shehui yanjiu de fangfa wenti 乡村的故事与国家的历史 – 以樟林为例兼论传统乡村社会研究的方法问题 [Stories from the villages and history of the country – a discussion on methodological challenges in researching traditional village societies using Changlim as an example], Zhongguo nongcun yanjiu 中国农村研究 [Rural Studies of China] (中国: 商务印书馆, 2003) ↩

-

新加坡潮州西河公会 [Singapore Teochew Sai Ho Association], Xinjiapo chaozhou xihe gonghui: Zhonghua minguo sa ba nian yi yue zhi liu yuefen huiwu baogao shu 新加坡潮州西河公会: 中华民国卅八年一月至六月份会务报告书 [Singapore Teochew Sai Ho Association: Working report for January to June 1949] (崇奉祖姑天后圣母略历 [Description of the Worship of the Ancestral Heavenly Queen Holy Mother], para 3). (新加坡: 新加坡潮州西河公会, 1949). (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RCLOS 369.25957 XJP) ↩

-

Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, vol. 2 (Edinburgh: John Mosman, 1727), 94. (From National Library Online) ↩

-