A Mapping of Southeast Asian Photobooks After World War II

By Zhuang Wubin

Introduction

There has been a surge in interest in photobooks since 2004, triggered by the publication of a series of richly illustrated volumes by publisher Phaidon, such as The Photobook: A History Volume I (2004), The Photobook: A History Volume II (2006) and The Photobook: A History Volume III (2014). The mastermind behind this series is British collector-photographer Martin Parr, with critic-photographer Gerry Badger as its lead writer. Today, there are fairs, festivals and symposiums dedicated to the photobook across the world. It is fair to say that Parr has been hugely responsible for surfacing the photobook as a field of interest and an object of desire.

In the preface of The Photobook: A History Volume I, Parr claims that the photobook is the “final frontier of the undiscovered” in the research of photography. Hence, his promotion of the photobook is an attempt to “narrate a new history of photography”.1 Together, Badger and Parr position the photobook at the chasms “between the aesthetic and contextual battalions in the photo-critical wars”, and between art and the mass medium, offering, in effect, a third way for photographers, curators, collectors and art historians to approach photography.2

Because the titles featured in these volumes are largely based on Parr’s enormous collection of photobooks, the selection is inevitably subjective and eclectic. Materials – such as company books and propaganda publications – frequently disparaged by art historians, curators and even photographers themselves receive serious treatment from the series, partly because Parr is personally invested in these photobooks. In a limited way, this has helped to broaden the art of photography. Parr adds, “We have gone out of our way to be inclusive, welcoming books from countries beyond the usual European- American axis, which are normally overlooked in other histories”.3 Hence, out of the 472 books chosen for the first two volumes of The Photobook series, some have been placed in the chapter “Other Territories: The Worldwide Photobook”, while productions from Japan are featured in the chapter, “Provocative Materials for Thought: The Postwar Japanese Photobook”.

While Parr repeatedly notes that all histories are subjective, what they have authored here is, of course, a global history written from a European perspective. This becomes apparent through a casual reading of the writings in these volumes where the references are overwhelmingly Euro-American and the arguments intended as universal proclamations. While they claim to attempt an “unofficial revisionist history” of photography through the valorisation of photobooks, their account is based on and inevitably bound to the official historiography, which continues to operate from imperial centres.4

This explains their claim, 10 years after the publication of The Photobook: A History Volume I, that there is now a global photographic culture and that the “photobook can be said to have been responsible for at least one conspicuous success in the ongoing story of globalization”.5 Globalisation, in this sense, refers to the uni-directional export of the photobook craze to the rest of the world, as there is little evidence in the publications of Parr and Badger to suggest that photobooks from any place in Asia, for instance, have significantly impacted communities of practitioners in the imperial centres. Furthermore, when they make the universalising claim that the photobook has been more important to the history of creative photography than the mass-media journal or the gallery print, it is clear that experiences in Southeast Asia have not been taken into account.6

While Parr and Badger assert that they have no interest in creating a new canon in photography, the Phaidon publications have effectively accelerated the canonisation and commodification of photobooks, chiefly benefitting Parr and his associates.7 In effect, their narrative leaves photobook productions from Southeast Asia outside of history and historiography. When a photobook from Southeast Asia appears in their selection, it serves to legitimise their global and eclectic taste. In other words, when they pick publications from the “peripheral” regions of the world to fit this global project, their selection inevitably helps to entrench the universality of the Euro-American narrative of photography.

Defining the Photobook

Before turning our focus onto Southeast Asia, it is worthwhile to revisit the ways in which the photobook has been defined in the current spate of canonisation. To quote Parr and Badger at length:

A photobook is a book – with or without text – where the work’s

primary message is carried by photographs. It is a book authored

by a photographer or by someone editing and sequencing the work

of a photographer, or even a number of photographers…. For the

most part, we have considered the photobook as a specific ‘event’

… in which a group of photographs is brought together between

covers, each image placed so as to resonate with its fellows as the

pages are turned, making the collective meaning more important

than the images’ individual meanings…. As we define it, the

photobook has a particular subject – a specific theme…. And

in the main, it will not simply be a survey of a photographer’s

‘greatest hits’, a career review. Monographs, or anthologies of

a particular photographer’s work at a given time in his or her

career have therefore not been included.8

Having provided what seems like an all-encompassing definition of the photobook, they immediately temper it by including in their selection the monographs of Henri Cartier-Bresson (The Decisive Moment, 1952) and Walker Evans (American Photographs, 1938), while excluding those made by some of the most important American Pictorialists, such as Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Weston and Ansel Adams. According to Parr and Badger, while the publications of the Pictorialists are typically sumptuous in production, they are more like anthologies than cogent photobooks.9 And yet, in The Chinese Photobook: From the 1900s to the Present (2015), co-edited by Parr – again based on his ever-growing collection – and WassinkLundgren (with Badger serving as a contributor), anthologies and exhibition catalogues such as Peking Light Society Annual (1929) and Holidays in Hong Kong (1968) from the milieus of Pictorialism are included in the selection.10 There is no doubt that these are significant publications in the history of China photography. The same can be said of the photobooks made by the aforementioned American Pictorialists, vis-à-vis the historiography of American photography. Why do Parr and his associates treat the productions of American and China Pictorialists differently? It is beyond the scope of this paper to delve into the question. But if I may suggest a possible reason, the discrepancy is perhaps due to the fact that the imprint of the American Pictorialists has already been fully acknowledged in the history of global photography, whereas the historiography of China photography remains a work-in-progress, especially for the English-speaking world. In this context, it is possible that Parr and WassinkLundgren had felt somewhat obliged to present a history of China photography via their valorisation of photobooks.

Returning to the issue of definition, U.S.-based Jörg Colberg, a widely followed proponent of the photobook, offers a slightly different view. He defines the photobook as a book that is viewed primarily for its photographs. This is different from a cookbook, for instance, which is probably read for its recipes rather than photographs.11 In contrast, Parr and Badger devote a full chapter in The Photobook: A History Volume II to the company book because many of the greatest photographers produced books that had been subsidised and commissioned by commercial corporations.12

Colberg considers albums, catalogues and monographs as the three subcategories of the photobook, differing from the definition offered by Parr and Badger. He also uses the term monograph differently from Parr and Badger, although it is clear that both parties actually valorise the same kind of object. Colberg demarcates the monograph from the catalogue, which typically does not feature a narrative arc. In contrast, it is very difficult to remove a photograph or a page from a monograph without dramatically altering the book. The placement of the photographs and the overall design create the “connective tissue” that makes the monograph more than just a sum of its parts.13

Like most proponents of the photobook, Colberg cannot help but speak of it in a somewhat mythologising manner. He adds, “When a photobook is made well, it is quite likely that you will not notice many of the great decisions that went into its making. That, ultimately, is the goal: while problems with photobooks are like hangnails that can be noticed even by those who do not know much about photobooks, many of the properties of perfectly made photobooks can only be appreciated by experts (designers, book binders, editors) or people who are aware of the various details to look out for”.14 Parr and Badger express a similar sentiment: “Often the difference between a great photobook and a good photobook is an indefinable quality that one recognizes when one sees it”. They add, rather perspicaciously, “Of course, photobooks have become extremely desirable objects in their own right. There is an element of fetishism at work”.15

Indeed, the transfer of the photobook hype to Southeast Asia has already generated a degree of fetishism. A case in point is the setting up of the Facebook group, ominously titled Photobook Fetish Singapore, by Invisible Photographer Asia (IPA) in 2015. Fetish for the smell of ink and the sound of a falling page in a photobook arrived via German printer Gerhard Steidl through his collaborations with designer Theseus Chan and DECK, a photo gallery in Singapore. Perhaps it is unsurprising that the fetish finds a ready audience in Singapore, one of the richest nations in Southeast Asia.

These definitions of the photobook have largely been articulated from Euro- American experiences and universalising desires. While not discounting their usefulness, they remain problematic on different levels. In this paper, I will surface and consolidate our experiences in making photobooks across Southeast Asia since 1945. In this context, it is paramount that we begin with a definition of the photobook that is as open-ended as possible. This will hopefully prevent certain types of publications from being excluded simply because they do not fit within the parameters of existing definitions. Here, I define the photobook as any publication with substantial photographic content. By surveying the collections in the National Library Board (NLB), I aim to create an evolving typology of photobooks based on our experiences in Southeast Asia.

What counts as a Southeast Asian photobook? Does the nationality of its author or location of its publisher define whether a photobook is Malaysian or Thai? In most cases, people would consider a book to be Vietnamese, if, for instance, its creator were Vietnamese. I do not disagree with such an inclination, even though this disguises the fact that the photobook, like photography itself, is a product that traverses national borders. Viet Nam in Flames, for instance, was published around 1969 with the support of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN).16 The photographers involved were Nguyê˜n Ma·nh Đan (b. 1925, Nam Dinh Province–d. 2019) and Major Nguyê˜n Ngo· c Ha· nh (b. 1927, Ha Dong–d. 2017, San Jose). The English-language version of the photobook offered an account of the Vietnam War from the perspective of the South Vietnamese establishment in an attempt to garner global support. Unsurprisingly, in the virtual sphere today, there are very few passing references in the Vietnamese language concerning this photobook.17 Perhaps to ensure its quality, Kwok Hing Printing Press in Hong Kong was entrusted with the printing of the photobook. Before the 1997 British handover to China, Hong Kong had been an important printing hub for publishers around the world, especially those with an active presence in East Asia and Southeast Asia. In short, Viet Nam in Flames is a hybrid product informed by Hong Kong print technology and a presumed target audience mainly located outside of Vietnam.

By extension, I wish to suggest that it is also possible to consider a photobook to be Laotian, for instance, if the subject matter is deemed to be Lao. The main intent is to temper the authority of the auteur, allowing those who appear in the photobook their inalienable rights as collaborators to claim (or reject) the publication. Naturally, instead of considering every tatty book published about Laos as a Lao photobook, it would only be productive to re-contextualise publications by photographers from elsewhere who have developed a longstanding and committed relationship with their sitters. By identifying a photobook through the claims of its sitters, we also allow them conversely to reject association with all the problematic publications in circulation.

Finally, it is worth remembering that Southeast Asia is not a regional framing that has come from within. The geographical terms of “Nanyang” in Chinese, “Nampo” in Japanese or “Nusantara” in Malay all predate “Southeast Asia”. The latter started creeping into popular use following the establishment of the Southeast Asia Command, an Allied force set up during World War II to “liberate” the region. After the war, driven by the U.S.’ desire to dominate the entire region between India and China, Southeast Asia became a region of strategic importance and an area of scholarship.18 Since then, the idea of Southeast Asia has gained limited traction from within. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to further unpack the imaginary of Southeast Asia, we should, at the very least, take it as an evolving geographical framing that may or may not include places such as Timor-Leste, Papua New Guinea, Sri Lanka, Hong Kong or even Christmas Island. This is not a call to increase the clout of Southeast Asia in order to redress the balance of power in Asia. Instead, this ever-morphing sense of the region serves to remind us of the problematic origins of Southeast Asia, while marking a productive space within to do inter-referencing work;19 in full recognition that we share enough similarities and differences in our cultural and political experiences to make critical comparisons worthwhile. This should prevent us from glossing over the imprint of Hong Kong or China, for instance, in our photobook experiences across Southeast Asia.

Locating Photobooks in NLB’s Collections

Photobooks have been produced since the inception of photography. Early examples include Anna Atkins’ Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions (1843–53) and William Henry Fox Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature (1844–46). In contrast, the current valorisation of the photobook form has been cultivated only since 2004. If we search the NLB catalogue using the keyword “photobook”, the results will be extremely limited. Previously, when a photobook was added to the NLB catalogue, the term “photobook” was not used to tag the entry’s subject field. The common term used then was “pictorial works”. The content is sometimes indicated, with the creation of subject tags such as “Vietnam – Pictorial works” or “Cats – Pictorial works”. However, the subject tags of “pictorial works” and “photobook” do not always refer to the same kind of object, as the former can denote, for instance, a book of illustrations. For the small number of publications tagged as “photobook”, almost all of them were published during and after 2007. An alternative is to look at the “physical description” field of each title in the NLB catalogue to ascertain if the publication contains illustrations or plates. Of course, this is not a sure-fire way of locating photobooks within NLB’s collections.

In May 2018, I met a photobook enthusiast from England who had recently relocated to Singapore. To acquaint himself with photobooks produced in Southeast Asia, he visited the reference section of the National Library at Victoria Street. Books on photography are typically found in the Singapore & Southeast Asia Collection, segregated from similar titles published elsewhere in the world. In the reference section, he noticed that photo-related publications from Southeast Asia, including photobooks, filled only slightly more than a shelf. As a region peripheral to the Euro- American centres of art, this was perhaps unsurprising to him, even though he remained unconvinced that the region had produced so few photobooks. In truth, his way of locating Southeast Asian photobooks in the National Library is common, even for Singaporeans who assume that Singapore has only ever published English books throughout its history. There are other Southeast Asian photobooks produced in other languages, which can be found in the library’s Malay and Chinese collections.

In fact, if we return to the definition of the photobook that I proposed earlier, then photobooks can be found across the different collections within NLB. Hence, in order to generate a typology of photobooks in Southeast Asia, it is important to physically flip through a publication to see if its photographic content forms a substantial component. Although it will take months or years to do so, this is technically possible for publications that can be physically accessed in the National Library’s reference section and the borrowing collections in libraries across the country. However, there are many publications that are not accessible on-site at the libraries, such as the Reference Used (RU) and PublicationSG (PubSG) collections. While the Rare Collection holds titles published before 1945, which fall beyond the scope of my research, the Reference Closed (RCLOS), RU and PubSG collections likely hold many publications that would fit my definition of the photobook. RCLOS titles can be accessed on-site at the National Library, but RU and PubSG collections are located off-site, complicating the research process, as they need to be requested specifically by title instead of browsing at the shelves.

On a practical level, it is impossible to flip through most of the titles within the NLB collections. This is testament to the massive collection that NLB has amassed over the years. Thus, one of the key challenges has been to make an intelligent guess based on the information available in each catalogue entry, so that the process of requesting for a potential photobook from the RCLOS, RU and PubSG collections would at least yield the right type of publication, while recognising the risk of missing out a peculiar publication that might complicate the typology that I wish to produce here. In short, the typology that I intend to map can only be evolving.

Translating the Photobook: Terminologies

Photographic publications have been produced by practitioners from the region long before the current craze in photobooks. As this craze trickles back to parts of Asia, the term “photobook”, in some cases, has had to be translated or re-adapted for localised usage. In Vietnam, for instance, sách anh, which literally means “photobook”, is commonly used.20 Similarly, in Myanmar, “photobook” is translated as dat-pone sar-oak.21 Sometimes, even a fairly straightforward translation of the term “photobook” might bring about a sense of consternation. For example, photo curator Ahmad Salman (b. 1970, Semarang) insists that the accurate translation of “photobook” into Bahasa Indonesia should be buku foto rather than* buku fotografi* because the latter can be taken to mean a book about photography. Buku foto, on the other hand, should be a publication that uses photography to deliver its content. Ahmad sounds pedantic only because he feels that Indonesians have historically been far too lax in using translated words and ideas.22

Meanwhile, there are many pre-existing terms in Southeast Asia, which precede the current photobook hype, some of which remain relevant today. In Mandarin, for instance, the formal term for a book, tushu [图 书], comprises the characters for “picture” and “book”, which already conveys the idea of a picture or an illustrated book. According to China photo historian Gu Zheng, in the present context “tushu has at least three denotations – a book of text, of images, or both – whereas an alternate term, huace [画册], refers more narrowly to a picture album composed of ink paintings, drawings, or other illustrations”.23

In other words, the terms tushu and huace already embody the myriad of possibilities that such a publication may offer, which is not necessarily conveyed through the somewhat prosaic nomenclature of the photobook. This quick consideration of the Mandarin term for the photobook is relevant for Southeast Asia, as many of the early photobooks published in the region since 1945 had been produced by Mandarin-speaking practitioners (or made for Chinese readers). The term huace is used to refer to some of these publications, such as The People and the Country (《人民与 国家》). This is a modest, saddle-stitched photobook produced by the Tanjong Pagar Branch of the People’s Action Party (PAP) in 1972, which visualises the evolution of the party branch as the national history of Singapore.24 Another common term in Chinese is tekan [特刊], or “special issue”. While most people associate kan with the term “periodical”, it can also mean “publication”. In Southeast Asia, news companies, Chinese schools and political parties, among others, have published numerous tekan, some of which are sumptuously illustrated with photographs, commemorating milestone events.

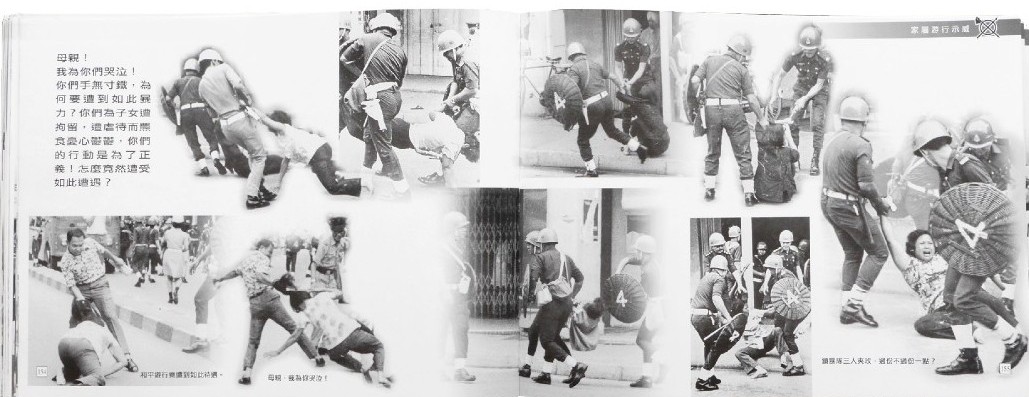

In the Thai language, nangsue phapthai [หนังสือ ภาพถ่าย] is a somewhat literal translation of the term “photobook”.25 It is a relatively new term that can already be found in the Thai dictionary.26 Phapthai and nangsue refer to “photographs” and “book” respectively. On the other hand, a term like samut phap [สมุดภาพ] was already in use during the reign of Rama V (r. 1868–1910). Samut means “book” while phap refers, more broadly, to “illustrations”. In a way, phap is similar to the Chinese term tu [图]. In other words, samut phap can be used to refer to a book of drawings, paintings or photographs. Other terms in use since the reign of Rama V include อัลบ้มั [pronounced as album] and pramuan phap [ประมวลภาพ]. In the 1970s, for instance, photobooks published to record the popular political movements of 1973 and 1976 were known as pramuan phap.27 Pramuan translates to “collection” and conveys a sense of archival in terms of putting together materials from different sources.28 These terms have since lapsed from popular usage.

This quick survey of terminologies referring to the photobook points to the longstanding practice of producing such publications in Southeast Asia. Despite the current interest in photobooks, its transfer from the metropole to Southeast Asia has been far from uneventful. In fact, without the active intervention of local practitioners trying to translate and make sense of the term “photobook” and the practice of photobook-making, it would have hardly mattered, here in Southeast Asia, what Parr and Badger have been trying to advocate. In this regard, the unevenness in the appreciation and making of photobooks across different parts of the region validates my point.

Translating the Photobook: Initiatives

In the decades that followed World War II, the state, elite class and corporations were the major drivers of photo publications in Indonesia (as was the case in other parts of Southeast Asia). Amateur photo clubs also published catalogues of their exhibitions. By the mid-80s, grandiose coffee-table books had become extremely popular, as the world’s most famous photographers were parachuted across the archipelago in search of “mystical, mythical Indonesia” to cash in on the “West’s surging interest in exotic lands”.29 In 1992, the national news agency of Antara (founded in 1937) decided to reopen its old office in Pasar Baru, Jakarta and convert it into Antara Photojournalism Gallery (GFJA), perhaps the first nonprofit space in Southeast Asia dedicated to photography. At least since the late 1990s, GFJA has been producing brochures, exhibition catalogues, zines and photobooks for its various initiatives. In short, without access to wealth or patronage, a photographer would have to work with an established publisher or exhibition space to publish a photobook. The current spate of photobook-making on a more independent basis has taken some time to germinate.

In 2008, with the support of German Photobook Prize, PannaFoto Institute (established in 2006), a non-profit foundation in Indonesia that focuses on photographic education and visual literacy, initiated a long-term relationship with Goethe-Institut in Jakarta to mount a series of photobook exhibitions.30 At the inaugural exhibition in 2008, some 100 books were on display, outnumbering the 20 or so attendees at the opening. The exhibition had received scant interest because, for aspiring photographers in Indonesia, the preferred mode of validating one’s work had always been to win awards, mount a solo show or have one’s photographs published in magazines.

In 2011, Ahmad Salman, one of PannaFoto’s founding members, set up the public Facebook group of Buku Fotografi Indonesia (Photo Books Indonesia) and encouraged its followers to post photographs of their photobooks to the group. This initiative worked to crowdsource the history of photobooks in Indonesia. The fact that people responded to Ahmad’s call suggests that the photobook form had gained a degree of traction by then. In that same year, photobook evangelist Markus Schaden (b. 1965, Cologne) ran a workshop sharing his book-making methodology in Jakarta.

Beyond the PannaFoto ecology, esteemed street photographer Erik Prasetya (b. 1958, Padang) was finally able to publish, in 2011, his first and longawaited photobook, Jakarta: Estetika Banal, with the most visible bookstore retailer in Indonesia, Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia. Funded by the Jakarta Arts Council (DKJ), the photobook brought to fruition Erik’s unwavering desire, over the past two decades, to photograph his adopted city of Jakarta. The endeavour bears testament to his intent to leave behind an artefact in the photobook form for future photographers in Indonesia. “Young people tend to work when everything is in place – when the money is there and the concept is ready. It’s not like that,” Erik explains. “When you shoot, you think of doing one good essay. And when you have 10 good essays, then you can make a book.”31

In April 2012, with the support of PannaFoto, Ahmad and photojournalist Julian Sihombing (b. 1959, Jakarta–d. 2012) initiated a series of kumpul buku (book gathering) in Jakarta. The event incorporated a bazaar of new and used photobooks, book signing sessions and public forums. Visitors were encouraged to share their photobooks during each gathering. Kumpul Buku has since inspired similar events across Indonesia, in Surabaya, Bandung, Solo and Yogyakarta.32 Over in Malaysia, on 1 May 2013, Faisal Aziz (b. 1988, Johor) and Liyana Jaafar founded the now-dormant Photobook Club Kuala Lumpur (PBCKL), which was partly modelled after the UK-based Photobook Club (established in 2011 by Matt Johnston). PBCKL positioned itself as a grassroots platform to promote and nurture discussions on the photobook, with the explicit aim of reaching the general public, beyond the photography community.33 PBCKL started with the couple’s personal collection of books and was informed by their desire to share them with the public. Its launch event was held at a lake garden in Selangor, featuring a discussion on photobooks and a browsing session at the garden’s benches.

Inspired by PBCKL and PannaFoto’s Kumpul Buku, Ridzki Noviansyah (b. 1986, Bandar Lampung) and Tommy N. Armansyah (b. 1974, Bandung) co-founded the Photobook Club-Jakarta in 2013. During its most active period, the club routinely organised public forums to discuss photobooks from around the world.34 On 15 and 16 November 2013, PBCKL was invited to a kumpul buku in Yogyakarta where they displayed a selection of Malaysian and Japanese books from its collection. The following year, on 18 May 2014, PBCKL hosted Ridzki for a talk at the Centre for Asian Photographers, Selangor, where he introduced a selection of Indonesian photobooks to the Malaysian audience. This brief account of photobook club initiatives helps to map the circuitous translation of photobook hype from Europe to Malaysia and Indonesia. It is also clear that practitioners from both countries inter-referenced the experiences of each other in localising the interest in photobooks.

In 2012, PannaFoto decided to try its hand at self-publishing. Led by current director and founding member Ng Swan Ti (b. 1972, Malang), they approached the endeavour with trepidation. Like Ng, many of her peers at PannaFoto came to photography during or after Reformasi, which was triggered by the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997 and resulted in the fall of Suharto in 1998. Since then, they had harboured hopes of publishing photobooks. The main challenge was to find a way to do so without substantial financial support. As a first attempt, Ng decided to play it safe and publish a book for her husband, fellow PannaFoto member Edy Purnomo (b.1968, Ponorogo), “who has no worry about his prestige as a photographer”.35 Ahmad and designer Bobby Haryanto worked on the project pro bono. The first print run of Passing was a tentative 200 copies. After everything for the launch had been booked PannaFoto promptly printed another 500 copies. Their initial uncertainty over the publication is reflected in the comparatively small size of the photobook, which measures 16 cm by 14 cm.

In 2013, Rony Zakaria (b. 1984, Jakarta) self published his first photobook, Encounters, to a warm reception. The market success of these two publications, with buyers largely coming from within Indonesia, helped, on a practical level, to offset production cost and instil a sense of confidence among local photographers to self publish their works. Since then, PannaFoto has published Ng’s Illusion in 2014, Mamuk Ismuntoro’s Tanah Yang Hilang in 2014 and Yoppy Pieter’s Saujana Sumpu in 2015. The institute did not finance any of these photobooks. Instead, each was financed differently – through private patronage, discounted materials or crowd funding. Beyond PannaFoto, other independent titles that have been published in Indonesia include Aji Susanto Anom’s Nothing Personal (published in 2013 by the Solo-based collective, Srawung Photo Forum), Arum Tresnaningtyas Dayaputri’s Goddess of Pantura (published in 2016), Flock Project’s Flock Volume 01 (published in 2016) and Tandia Bambang Permadi’s Coming Home (published in 2017). While this brief account may give the impression of a vibrant photobook publishing culture in Indonesia, it has to be framed against the context of the country’s population of over 250 million. In this sense, the photobook community – in terms of its producers, buyers and enthusiasts – remains extremely small.

Nevertheless, it is obvious that the ecology of photobooks in Indonesia has become more sophisticated over the past few years. In 2014, PannaFoto organised another photobook exhibition in Jakarta, in collaboration with Goethe-Institut. During the event, it invited Ahmad, publisher Lans Brahmantyo (b. 1966, Surabaya) and educator-photographer Kurniadi Widodo (b. 1985, Medan) to curate 20 Indonesian photobooks for the exhibition. In this way, the community in Indonesia started historicising its photobook production.

In 2015, Aditya Pratama (b. 1983, Jakarta) and Ferry Ferdianta Ginting (b. 1983, Bandung) established Unobtainium, an online store specialising in photobooks. Without a physical bookstore dedicated to the photobook, Unobtainium makes absolute sense, especially in a sprawling archipelago like Indonesia. It started by stocking foreign books, which were hard to find in Indonesia. A year later, they began selling Indonesian photobooks, which, in truth, turned minimal profits. Nevertheless, Aditya feels that it is part of Unobtainium’s responsibility to stock local books as a means to grow the photobook community.36 It has also given them an edge in the international market, with foreign collectors interested in Indonesian photobooks actively seeking Unobtainium out. In fact, Martin Parr recently bought a stash of Indonesian photobooks from them.

A quick comparison can be made with the situation in Thailand when photographer Akkara Naktamna (b. 1979, Bangkok) established the Good Art Book online store in 2015. Its intention is to encourage Thai artists to produce their own photobooks by establishing a sales and promotion channel that offers more favourable terms and greater visibility to practitioners who want to self-publish. The logic of strength in numbers is at work here, similar to Unobtainium, with Good Art Book focusing predominantly on photobooks made by Thai practitioners. Its listing of Thai photobooks is shorter than Unobtainium’s stock list of Indonesian photobooks, reflecting the liveliness of photobook publishing in Indonesia. With its Thai focus, Good Art Book receives more overseas than local orders.37

According to Aditya, the market for photobooks in Indonesia has been recalibrated in recent years. A few years back, people would buy a photobook with the simple intention of owning one. Today’s buyers have become more discerning. While Aditya expresses this as a cautionary note vis-à-vis the long-term sustainability of the photobook market in Indonesia,38 I feel that this is actually a healthy development in terms of evolving the taste of local buyers in purchasing photobooks and appreciating photography. In any case, beyond mounting an exhibition, the photobook has become an acknowledged means among Indonesian photographers to showcase their work. This is one of the most discernible outcomes in translating the photobook hype in Indonesia.

This prompts us to cast a glance at the photobook ecology in the Philippines. At first sight, the Philippines would seem primed for the translation of the recent photobook craze. The country boasts a rising middle-class, critical mass in terms of population, a vivacious heritage of photographic practices, and general openness towards American trends and information. It has had a long history of producing photobooks, starting perhaps with Filipino photographer Felix Laureano (b. 1866, Patnongon, Antique Province –d. 1952) who, in 1895, published the album-book Memories of the Philippines in Barcelona. A cheaper facsimile was made in 2001 in the Philippines.39 Short of narrating a linear history here, it is worth pointing out that the fall of Marcos heralded a spate of photobooks being published, including Kasama: A Collection of Photographs of the New People’s Army of the Philippines (published in 1987), which garnered the National Book Award for its photographers Alex Baluyut (b. 1956, Manila) and Lenny Limjoco (b. 1954, Manila–d. 2012). Other notable photobooks that followed in that period include Depth of Field: Photographs of Poverty, Repression, and Struggle in the Philippines (published in 1987), Sipat: A Collection of Photographs from the Philippine Collegian 1987–88 (published in 1988), Limjoco’s Larawan: Portraits of Filipinos (published in 1989) and Dwell on Their Faces, Probe Their Thoughts: Photographs of Filipino Children (published in 1990).

As a parallel, when Indonesian president Suharto stepped down during the Reformasi in 1998, the lid was suddenly removed and several critical photobooks (including exhibition catalogues) were published during that period, including Oscar Motuloh’s satirical Carnaval (published in 2000) and Eddy Hasby’s East Timor: The Long and Winding Road (published in 2001).40 On hindsight, the latter received limited interest then possibly because the photobook form was seen as a luxury object beyond the means of most Indonesians who were still recovering from the economic fallout of the Reformasi. Eddy’s interest in East Timor might have also been misinterpreted by some as a slight against Indonesia’s sovereignty. But, as photobook-making gains traction in Indonesia, Eddy’s book has since resurfaced as an important reference.

In the Philippines, an important publisher of critical books since the fall of Marcos has been the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ), a non-profit media agency established in 1989. While it does not have a specific focus on photobooks, PCIJ did publish Alex Baluyut’s Brother Hood in 1995, an in-depth photo story on police brutality in Manila. The book registered record sales and won Baluyut his second National Book Award. In 2002, PCIJ published veteran photographer Sonny Yabao’s Memory of Dances, which examines, through his enigmatic photographs, the story of cultural loss experienced by the Bugkalot and Igorot at Nueva Vizcaya, the Tagbanua at Coron and the Manobo at Mount Apo.41

Sheila S. Coronel (b. 1958), one of Asia’s most eminent investigative journalists, served as PCIJ’s executive director from 1989 to 2006. Apart from the freedom heralded by the post-Marcos era, Coronel notes that the economy had improved significantly enough for people to start buying books, fuelling even the publication of expensive coffee table books during the 1990s. In PCIJ’s remit, photography remains integral to many of its publications because the medium is essential to the documentation of wrongdoing, such as police abuses or corruption in procurement and public works, while lending credibility and humanity to its investigative work.42 While photography took centre stage in Brother Hood and Memory of Dances, Coronel admits that the production value for both photobooks was deliberately modest in order to keep costs low, so as to make them more affordable and extend their reach. In fact, she suspects that buyers of both photobooks mainly came from beyond the photography community.43

Since the valorisation of the photobook by Parr and Badger, there have been attempts to translate that interest to Manila. In 2015, contemporary artist Wawi Navarroza (b. 1979, Manila) established Thousandfold, which featured a public photobook library and the Thousandfold Small Press, an initiative to encourage Filipino practitioners to make small-edition photo publications. Thousandfold also initiated the Photobook Club Manila in 2015. Some of these initiatives were cut short due to a fire in 2016 that destroyed Navarroza’s studio.

In 2017, Filipino photographer-printer RJ Fernandez (b. 1979, Manila) officially established MAPA Books, an independent publishing house in London. Predictably, its first photobook titles are dedicated to two Filipino photographers: Tommy Hafalla’s Ili (published in 2016)44 and Veejay Villafranca’s Signos (published in 2017). Informed by Fernandez’s desire to bring the quality of production in London to the Philippines, and given that MAPA Books prints their titles in Italy, the pricing of these photobooks is at a similar level to that of a European publication.45 Thus, it remains to be seen whether the price-point of both publications will hinder their broader reception in Manila.

In Java, it is clear that the photography community has become invested in the photobook form. Their support in terms of interest and purchases directly fuels the photobook ecology in Indonesia.46 While they may have differing views on the medium, senior photographers remain active as role models, mediating the relevance of photobooks in local terms. There have also been initiatives to promote the photobook among Filipino practitioners. They are typically short-lived or one-off endeavours, taking the form of a photobook exhibition or a booth at the art fair. The unglamorous and long-term work of creating a community invested in the photobook has not been taken up, unlike the interventions of PannaFoto Institute or GFJA in Indonesia. Some of the senior photographers have also faded from the scene, with the likes of Baluyut and Yabao moving out of Manila and relocating to Laguna.

An attempt by Photobook Club Manila in 2017 to replicate Buku Fotografi Indonesia’s initiative to crowdsource the history of Philippine photobooks (via its Facebook group) also fizzled out before it could gain any traction. There seems to be a defeatist sentiment in the Filipino photography scene. This is most evident when a senior photographer, somewhat exasperated, said that she is simply too broke to make a photobook, as though the modest movement of independent photobook publishing across Java has been undertaken only by the privileged class. This is far from the truth. When Ng Swan Ti decided to set the first print run of Edy Purnomo’s Passing at 200 copies, it was based on the calculation that they would be able to coerce at least 200 of their friends to support the project.47 Is it impossible to garner similar support for an accomplished Filipino photographer in Manila? I have no idea. Nevertheless, it is obvious that Manila lacks respected interlocutors who have a sustained commitment in translating the photobook interest and making it relevant to local practitioners. While it is certainly useful to learn about the production of photobooks in Europe and America, the experiences of practitioners in Java may be of greater relevance to those in Manila.

An Evolving Typology of Photobooks in Southeast Asia

Instead of proposing a catchall definition for the Southeast Asian photobook, I offer here an evolving typology of such publications based on the NLB collections. This typology is largely derived from the function and intent of each photobook, with its content a secondary consideration. I propose this typology, not because I wish to create another system to pigeonhole a particular publication. This typology will only be productive if it is thought of as a mapping of photobook experiences in Southeast Asia since 1945. The typology should help us think of the kinds of photobooks that have been produced under specific desires and conditions across the region. In this way, the desires and conditions that inform the making of a particular kind of photobook can then be compared to the situation elsewhere, beyond Southeast Asia. It is true that a particular title can be placed under several categories. Ideally, this should open up different ways of reading a particular photobook.

There is a degree of tentativeness in proposing this typology, given the way NLB catalogues and organises its collections, as highlighted earlier in the essay. As and when a photobook that complicates this typology is encountered, it will become necessary to include a new type.

These are the types of photobooks:

1. Photobooks as Performing State Politics

2. Photobooks as Repository of Marginalised Politics

3. Exhibition Catalogues

4. Photobooks as Portfolio/Exhibition

5. Corporate Books as Photobooks

6. Minjian (民间) Books as Photobooks

7. Scenes and Landscapes: Photobooks as Record

Let me explain the typology in greater detail.

1. Photobooks as Performing State Politics Given the cost of producing a photobook, the state has always been a major publisher of books with significant photographic content. Photography is seen as an efficient way to convey the state’s agenda, especially when the intended audience is deemed to be an unwilling reader of text. In this sense, The People and the Country (《人民与国家》) and Viet Nam in Flames can be thought of as photobooks that perform state politics. While the latter was intended for an English-speaking audience, presumably located outside of South Vietnam, The People and the Country was meant for domestic consumption, especially among Singapore’s Chinese-reading population.

While the state might understandably be invested in advancing its agenda through photobooks, it is worth noting that there have also been numerous photo publications, credited to photographers and commercial publishers, which willingly mirror the state narrative. Quite a number feature the works of foreign photographers. A good example is The Royal Family of Thailand, authored and photographed by London-based Jewish photographer Reginald Davis.48 A fellow of the Royal Photographic Society (RPS) of Great Britain since 1971, Davis made a name for himself photographing royal families across the world. While the photobook was published in London in 1981, it was printed and bound by Dai Nippon’s Hong Kong office. The Japanese printing house had established its Hong Kong branch in 1964, bringing its services one step closer to Southeast Asia.

Published in English, The Royal Family of Thailand was distributed by Central Department Store, a retail giant from Bangkok. While this suggests that the English-reading public in Thailand would have reasonable access to the photobook, it is likely that the publication would have been of interest to readers beyond the country. The blurb on the front flap of the dust jacket states: “In an age of turmoil in South-East Asia, the constitutional monarchy of Thailand, situated as it is in a sub-continent of intensive political change, has variously excited outside observers with bafflement, curiosity and respect. How can such a kingdom flourish, the world asks, how can it even survive such an environment?” The turmoil of the region mentioned here probably refers to the October 1973 uprising and the 6 October 1976 massacre in Bangkok, the fall of Saigon in 1975, the takeover of Cambodia by the Khmer Rouge and its subsequent dispersal in 1979 by Vietnamese forces, as well as the Communist-turn in Laos.

The Thai kingdom’s stability then, as spelt out by the book’s blurb, was only guaranteed by the “extraordinary power of the good exercised by Their Majesties King Bhumipol and Queen Sirikit over the Thai people”. The photographs subsequently show the royal family decked in regalia, traversing the country and visiting their subjects. More crucially, readers are afforded a glimpse of the royal family in scenes of leisure and pleasure, reminiscent of the colourful fashion spreads of that era. Davis’ photographs appear in contrast to the turmoil referenced in the blurb. The circulation of Davis’ photobook through the English-speaking milieu helped to popularise the perception that the well being of the Thai nation was inevitably pegged to the steady hands of the royal family.

2. Photobooks as Repository of Marginalised Politics The second kind of photobook can be thought of as publications produced in partial response to the previous type of photobook. Broadly speaking, these photobooks use the book format to record, recall and visualise other articulations of politics that have been made marginal by the state or mainstream society. They are sometimes, though not always, produced by civil society. For instance, Labour Party of Malaya Album of Historical Photographs (《马来亚劳工党历史图片集》) was published by surviving members of the political party in 2000, decades after its deregistration in 1972.49

The Labour Party of Malaya (LPM) originated from an amalgamation of different labour parties across Malaya in 1952, and gained control of the George Town Municipal Council during the Penang municipal council elections of December 1956. In the 1959 General Election, under the Socialist Front (SF) coalition, LPM won six parliamentary seats and 13 seats in different state assemblies. Internal disagreements over the formation of Malaysia in 1963, waves of arrests without trial targeting many LPM cadres under the Internal Security Act (ISA) and the party’s eventual decision to boycott parliament gradually brought about its demise.50

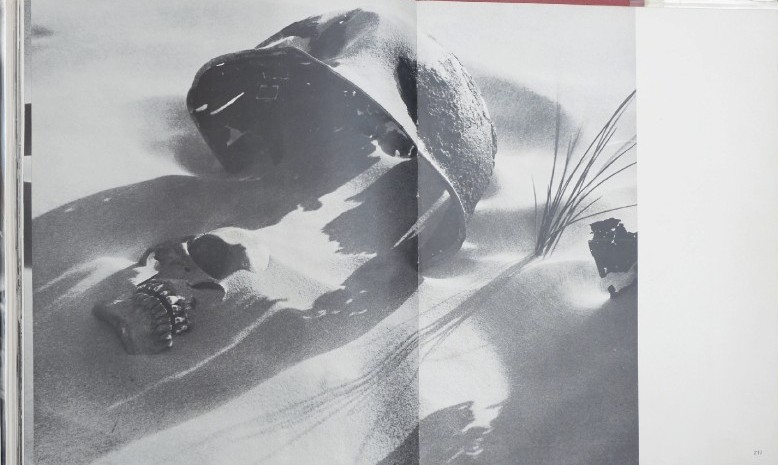

In its introduction, editor’s foreword and afterword, the fact that LPM members risked potential state reprisal to preserve these images for posterity is repeatedly mentioned or implied. The afterword notes the publication’s aim to “reflect the real side of Malayan history” through these historical photographs. While the photobook focuses on the milestones of LPM, the latter sections strive to visualise the state violence enacted on its comrades and their family members. To heighten the visual drama of the forceful dispersals of family members outside a detention camp, a strategy of montage and juxtaposition is used, recalling the graphic nature of protest books from across the region.51 Portraits of former LPM and SF detainees, neatly laid out in a grid, run for nine pages in the closing section of the photobook, a reminder of their sacrifices for Malaysia.52

3. Exhibition Catalogues

The cost of producing photobooks remains exorbitant for most photographers in Southeast Asia. Publications made in conjunction with exhibitions, published or partially subsidised by the exhibiting venue, offers an opportunity for practitioners to produce photobooks. While some of these publications provide nothing more than a listing of exhibited works, others are well designed and offer a narrative or political reading that is not limited to the content of the printed photographs.

In the decades following the end of World War II, as the nations in Southeast Asia broke away from colonialism, a particular kind of exhibition catalogue abounded – those produced by amateur photo clubs. As advocates of Pictorialism or salon photography, these clubs offered tutelage to eager adherents interested in learning the medium, prior to the institutionalisation of photo education in academies and universities across the region.53 They operated through the logic of strength in numbers and typically enjoyed patronage, directly or otherwise, from the state or elite class. An example is Pictorial Photography: Seven Men Photo Exhibition, an exhibition catalogue published by the Photographic Society of Singapore (PSS) in 1965.54 The PSS originated from the Singapore Camera Club, which was established in 1950 under the British-backed Singapore Art Society umbrella. Police inspector Yee Joon Toh served as its founding president. Since its inception, the club has published numerous catalogues for its exhibitions and competitions. Many of these catalogues are forgettable, with a few exceptions, including Pictorial Photography: Seven Men Photo Exhibition, which was published in conjunction with a group exhibition at Victoria Memorial Hall. The exhibition featured the works of seven Chinese male photographers active in the milieu of salon photography, namely: Lee Lim, Mun Chor Koon, Tan Boon Yean, Wang Su Fah, Wu Peng Seng, Yam Pak Nin and Yip Cheong Fun (b. 1903, Hong Kong–d. 1989, Singapore).

Then Minister for Culture S. Rajaratnam officiated the opening of the exhibition on 5 March 1965. In the catalogue’s foreword, Rajaratnam wrote, just months before Singapore was ousted from Malaysia, “Photography is an art form which cuts across barriers of language, race and creed. In our multiracial society it is an effective and essential method of communication to promote better understanding amongst the various communities of our new nation. … In the not too distant past, it was not uncommon for Singapore to be dismissed as ‘a cultural desert’, but it is gratifying to note that world opinion has changed completely, thanks to the efforts and diligence of our people and organisations such as yours [PSS] which have focused attention on our cultural life”.55

An important aide to Lee Kuan Yew in the PAP, Rajaratnam’s words held sway in terms of the way photography would be mobilised for the party’s agenda and to mark Singapore’s relevance to the world. It is likely that Chua Soo Bin (b. 1932, Singapore) helped to produce or design the thoughtful catalogue.56 Chua had started out as a PSS member whose practice would eventually evolve to encompass advertising and portraiture. In 1988, Chua was conferred the Cultural Medallion (Photography), the highest award for the arts in Singapore.

The dust jacket of Pictorial Photography: Seven Men Photo Exhibition presents a group portrait of the featured photographers staring at the camera and the intended viewers of this publication. The end-paper of the book presents the negative image of this group portrait. A crop of the portrait reappears in the photobook, above the spread listing the featured works. This interplay of positive and negative images articulates the designer’s keen awareness of the photographic process and helps to project, through the photographers’ unwavering gaze (at the viewers), their modernist profile as art photographers. Echoing the title of the photobook, the numeral seven is repeated in the opening spread of each photographer’s chapter of his works. As a whole, the design of the catalogue exudes confidence that seems befitting of that era and the status of the exhibiting photographers.

4. Photobooks as Portfolio/Exhibition

Earlier, I argued that it is important to re-contextualise certain exhibition catalogues as potential photobooks. Here, the focus is on photobooks that are conceived as an exhibition or portfolio of the practitioner’s work. In certain cases, these photobooks function as a manifesto of the photographer’s practice. It is also possible to place the artist’s book in this section. In this way, the collaboration between artist Robert Zhao (b. 1983, Singapore) and designer Hanson Ho, resulting in publications such as Mynas,57 can be placed in dialogue with salon photographer Chua Tiag Ming’s Photography in Action (《哲民影集》).58

While Zhao’s photobook feels sumptuous and very designed, which transforms his work into a tactile experience, Chua’s book, designed by fellow salon photographer Foo Tee Jun, seems almost unadorned. The front end-paper features a picture of Chua prone on the ground, photographing a lady (whom I presume to be his wife, given that his dedication to her appears in the top left corner). Chua’s wife had apparently also contributed to the photobook by touching up the photographs and proofreading the English text.59 On one hand, Chua’s photobook looks like a portfolio of his best hits. The accompanying captions oscillate between providing context to the images, articulating his perspectives on the subject matter, and delving into the technical issues of a particular photograph. On the other hand, the book also features text by other esteemed salon practitioners on various aspects of photography. Hence, Chua’s photobook feels like a hybrid object that serves as a portfolio, manual for other photographers, as well as a vehicle to express his thoughts.

5. Corporate Books as Photobooks

Corporations have always sought out and commissioned the best photographers for their book projects. This is another avenue where we may encounter exemplars of photobooks in Southeast Asia. One curious example from NLB’s collections that merits a quick mention is Brunei Darus Salam: A Pictorial Review of the Land and People, published by Brunei Shell Petroleum Company.60 At first glance, this photobook published in 1968 was to commemorate the coronation of Hassanal Bolkiah, the current sultan and prime minister of Brunei. The photobook takes us through the ways-oflife and development of the state, with the closing section dedicated to the extraction of oil, the raison d’être for Shell’s existence in Brunei. Within my proposed typology, this publication can be thought of as a photobook that performs state politics. However, it is also a corporate book published by the oil company to portray Brunei, on behalf of the state, which only attained independence from the United Kingdom in 1984. Locating this publication in this category allows us to consider the intricate connection between the oil conglomerate and logic of political power in Brunei.

6. Minjian (民间) Books as Photobooks

In Southeast Asia, another source of photobooks comes from the minjian (民间). As Taiwanese theorist Chen Kuan-Hsing points out, minjian refers to “a folk, people’s, or commoners’ society, but not exactly – because while min means people or populace, jian connotes space and in-betweenness”.61 In short, minjian refers to the “space where traditions are maintained as resources to help common people survive the violent rupture brought about by the modernising of state and civil society”. The examples of minjian groups that Chen gives include religious sects, sex workers and street vendors.62 It is also possible to think of the Chinese-medium schools in Malaysia and Cambodia, self-help groups and clan associations across the region, as well as certain cultural organisations (such as KUNCI Cultural Studies Centre at Yogyakarta, Lostgens’ Contempoary Art Space at Kuala Lumpur and Bras Basah Open in Singapore) as different manifestations of the minjian society in Southeast Asia. While the term minjian is not as commonly used in Southeast Asia as compared to Taiwan (where Chen is based), a semblance of the minjian that Chen evokes continues to exist across Southeast Asia.

For the purpose of discussion, a publication such as A Pictorial History of Hin Hua High School can be considered a minjian photobook.63 Founded in 1947 and funded partially through minjian society, Hin Hua is a Chinese independent school in Klang, Malaysia. This 364-page photobook is part of a three-volume publication that commemorates the arduous journey Hin Hua High School has undertaken to provide education in Klang. The publication’s intention is to record the sacrifices of its founders, tying the photobook to the Chinese cultural tradition and placing it within the context of the marginalisation of Chinese experiences within the national history of Malaysia.64 In this way, this photobook has been bestowed with a burden larger than just the recording of Hin Hua’s development over the decades.

Printed on an understated yet elegant paper stock, the publication features a wonderful selection of historic and recent photographs, juxtaposed against archival materials and news reports relating to Hin Hua High School. The layout is an attempt to translate the viewing experience of a physical exhibition into the book format. Interestingly, the designer of the book is TsuJi Lam, a founding member of Lostgens’ Contemporary Art Space. Despite its name, Lostgens’ is actually more of a minjian space-collective facilitating initiatives in art, politics, heritage and culture. Over the years, it has intervened in community sites that have come under the threat of gentrification and destruction. In these interventions, one of its key initiatives has been the collection of oral history interviews and old photographs from members of the affected communities. These photographs are then displayed onsite, perhaps in a disused shop lot or kopitiam (coffeeshop), as a means to generate discussions. Very often, the photographs serve as an additional trigger for other community members to come forward, hence crowdsourcing a minjian history of the affected sites. Lam’s involvement in these initiatives can be perceived as a parallel to her design work in A Pictorial History of Hin Hua High School.

7. Scenes and Landscapes: Photobooks as Record

Prior to the proliferation of television sets and budget travel, periodicals and photobooks helped to bring views of the world to eager audiences across Southeast Asia. In some cases, these publications helped Southeast Asians experience the formation and boundaries of the nations to which they pledged allegiance by bringing them sights and landscapes from these newlyformed states. In other instances, they brought – and continue to bring – us views from faraway places. Some of these photobooks might have been made to mirror the state agenda. But the ethos of time has somewhat tempered their political motivations, rendering these publications as records from a different time and place.

An obvious example is Characters of Light: A Guide to the Buildings of Singapore, written and photographed by Marjorie Doggett (b. 1921, Sussex, UK–d. 2010, Singapore).65 Writer, publisher, gallery owner and impresario Donald Moore (b. 1923, Leicestershire, UK–d. 2000) was responsible for putting out Characters of Light in 1957. Doggett and Moore arrived in Singapore through the colonial milieu – the Royal Air Force posted Doggett’s husband to the island in 1947, while Moore arrived that same year to work for British publishing houses. The opening section of Doggett’s book features a verse penned by Sir Stamford Raffles, which reads: “Let it still be the boast of Britain to write her name in characters of light; let her not be remembered as the tempest whose course was desolation, but as the gale of spring reviving the slumbering seeds of mind and calling them to life from the winter of ignorance and oppression. If the time shall come when her empire shall have passed away, these monuments will endure when her triumphs shall have become an empty name.”

Doggett wrote in the foreword that her book made “no pretence to be a technical work on Colonial architecture”.66 In the short history of Singapore that follows the foreword, the narrative of Singapore’s evolution from a mangrove swamp to a great port, a development “beyond Raffles’ wildest dreams”, is predictably repeated, with no mention of Britain’s exploitation of Malaya before and after World War II.67 While it is doubtful that the photobook was ostensibly made to perform the colonial state’s politics, Doggett’s straight-up and considered recording of colonial buildings, riverside godowns, elegant mosques and elaborate temples should be seen as a tacit acknowledgement (and visualisation) of the flourishing of Singapore through British colonialism.

In 1960, the Doggetts became Singapore citizens. In 1985, Times Books International made a flimsy reproduction of the original book, with a different sequence of photographs and the addition of previously unpublished images.68 The new foreword explained that the rationale for the reproduction was nostalgia for old Singapore and Doggett’s plea for heritage conservation. After accounting for the fact that a newly independent nation would have little interest in the colonial past, Doggett wrote: “But time has its mellowing effect. History is always a mixture, and whether good or evil prevails for a time, each period has its place in the making of a nation”.69 Indeed, Doggett’s photographs come to us today with their colonial imprint somewhat withered, only to be detected in the young nation’s nostalgia for its distant past.

Conclusion

In closing, this essay has offered a tentative overview of our photobookmaking experiences in Southeast Asia, based on NLB’s collections. It is also clear that much work remains to be done. Our knowledge of photobooks published in chu~’ quô´c ngu~’ or the Thai language, for instance, remains limited. Furthermore, despite the years of upheaval that countries like Cambodia and Myanmar have experienced in the recent past, it is problematic to assume that photobook-making had been halted simply because of that. The typology that I have proposed should help us broaden the scope in terms of locating and defining our photobook experiences in the region. To this end, it is also an evolving typology that invites further scrutiny. Finally, photobooks should not be studied only in relation to the history of photography in Southeast Asia. In fact, future reseachers would be able to cast a different light when considering our photobook experiences through the perspectives of design history, evolution of print technology and the routes of distribution (of materials needed to make photobooks and how they are being sold across the world). 68

Acknowledgments

Zhuang Wubin would like to thank everyone who has contributed to this paper. In particular, he would like to thank the following for their kind assistance: Karen Strassler, Sandra Matthews, Clare Veal, Kong Leng Foong, Joanna Tan, Gladys Low, Nicholas Y. H. Wong, Justin Zhuang, Lee Chang Ming and Michelle Wong.

REFERENCES

Aditya Pratama. Photo Books From Indonesia – Development and Role of Communities, November 2017, accessed 30 June 2018, https://www.goethe.de/ins/id/en/kul/mag/21126073.html.

Anderson, Benedict. A Life Beyond Boundaries. London: Verso, 2016. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 907.202 AND)

Brunei Shell Petroleum Company. Brunei Darus Salam: Gambar2 Menunjokkan Negeri Dan Pendudok-Nya. Brunei Darus Salam: A pictorial review of the land and people] ([Seria]: Brunei Shell Petroleum, [1968?]. (From National Library, Singapore call no. Malay R 959.55 BRU)

Cheah, Boon-Kheng. “The Left-Wing Movement in Malaya, Singapore and Borneo in the 1960s: ‘An Era of Hope or Devil’s Decade’?” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 7, no. 4 (December 2006): 634–649, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14649370600983196.

Chen, Kuan-Hsing. Asia As Method: Toward Deimperialization. Durham [N.C.]: Duke University Press, 2010. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 950.072 CHE)

Chua, Tiag Ming 蔡哲民. Zhemin ying ji 哲民影集 [Photography in action]. Singapore: s.n., 1978. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese R 779 CTM)

Colberg, Jorg. Understanding Photobooks: The Form and Content of the Photographic Book. New York: Routledge, 2017. (From National Library Singapore, call no. 745.5938 COL-[REC])

Coronel, Sheila. Memory of Dances. Manila: Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, 2002. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.90049921 COR)

Davis, Reginald. The Royal Family of Thailand. London: Nicholas Publications, 1981. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.3040924 DAV)

Doggett, Marjorie. Characters of Light: A Guide to the Buildings of Singapore. Singapore: Donald Moore, 1957. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 722.4095957 DOG)

–––. Characters of Light. Singapore: Times Books International, 1985. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 722.4095957 DOG)

Hafalla, Tommy. Ili. Manila: MAPA Books, 2016. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RART 779.2095991 HAF)

Laureano, Felix. Recuerdos de Filipinas : album-libro : util para el estudio y conocimiento de los usos y costumbres de aquellas islas con treinta y siete fototipias tomadas y copiadas del natural [Memories of the Philippines: Album-book; A tool for the study and understanding of the ways and customs of these islands with thirty-seven phototypies taken and copied from real life]. Mandaluyong, Philippines: Cacho Publishing House, 2001. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.9 LAU)

Liang, Wen Gui 梁文贵. Ren min zhen xian xuan yan 人民阵线宣言 [The people and the country]. 新加坡: 人民阵线, 1972. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 329.95957 LWK)

Nguyen, Manh Dan and Nguyen Ngoc Hanh. Vietnam in Flames. [s.i.: s.n.], 1969. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RUR 959.7043 NGU)

Parr, Martin and Gerry Badger, eds. The Photobook: A History, vol. 1. London: Phaidon, 2004. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RART q770.9 PAR)

–––. The Photobook: A History, vol. 2. London: Phaidon, 2006. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RART q770.9 PAR)

–––. The Photobook: A History, vol. 3. London: Phaidon, 2014. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RART q770.9 PAR)

Parr, Martin and WassinkLundgren, eds. The Chinese Photobook: From the 1900s to the Present. New York: Aperture Foundation, 2015. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RART 770.951 CHI)

Photographic Society of Singapore. Photographic Society of Singapore, Seven Men Photo Exhibition at the Victoria Memorial Hall, 6th and 7th March, 1965. [Singapore: Photographic Society of Singapore, 1965]. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 779 PHO)

Reed, Jane Levy. Toward Independence: A Century of Indonesia Photographed, ed. Jane Levy Reed. San Francisco: Friends of Photography, 1991. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RUR 959.800222 REE)

The Long and Winding Road East Timor. Jakarta: Alliance of Independent Journalists, 2001. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RART q779.91598092 HAS)

Renmin yu guojia 人民与国家 [The people and the country] (Singapore: P.A.P. Tanjong Pagar Branch, 1972)

Zhao, Renhui Robert. Mynas. Singapore: Institute of Critical Zoologists, 2016. (From PublicationSG)

Feng zhi juan: Xing Hua tu zhi 风之卷: 兴华图志 [A pictorial history of Hin Hua High School]. Malaysia: 兴华中学, 2013. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RSEA 373.5951 XHZ

Malaiya lao gong dang li shi tu pian ji 马来亚劳工党历史图片集 [Labour Party of Malaya album of historical photographs]. 吉隆坡:劳工党党史全国工委会, 2000. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RSING 324.259507 MLY-[YOS])

Zhuang, Wubin 庄吴斌. Shi hui dong nan ya she ying jiao xue de tu pu 试绘东南亚摄影教学的图谱 [Teaching photography in Southeast Asia: Altentative mapping]. 台北市: 国立台北艺术大学关渡美术馆, 2017. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RSEA 770.71059 ZWB)

NOTES

-

Martin Parr, “Preface,” in The Photobook: A History, vol. 1, ed. Martin Parr and Gerry Badger (London: Phaidon, 2004), 4–5. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RART q770.9 PAR) ↩

-

Martin Parr, “Preface,” in The Photobook: A History, vol. 3, ed. Martin Parr and Gerry Badger (London: Phaidon, 2014), 5. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RART q770.9 PAR) ↩

-

Martin Parr and WassinkLundgren, eds., The Chinese Photobook: From the 1900s to the Present (New York: Aperture Foundation, 2015), 50, 350. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RART 770.951 CHI) ↩

-

Jorg Colberg, Understanding Photobooks: The Form and Content of the Photographic Book (New York: Routledge, 2017), 1. (From National Library Singapore, call no. 745.5938 COL-[REC]) ↩

-

Martin Parr, “Preface,” in The Photobook: A History, ed. Martin Parr and Gerry Badger (London: Phaidon, 2006), 6. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RART q770.9 PAR) ↩

-

Colberg, Understanding Photobooks: The Form and Content of the Photographic Book, 1–2. ↩

-

Colberg, Understanding Photobooks: The Form and Content of the Photographic Book, 12. ↩

-

Manh Dan Nguyen and Nguyen Ngoc Hanh, Vietnam in Flames ([s.i.: s.n.], 1969). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RUR 959.7043 NGU) ↩

-

I would like to thank Ha Dao for pointing out this observation. ↩

-

Benedict Anderson, A Life Beyond Boundaries (London: Verso, 2016), 35–38. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 907.202 AND) ↩

-

Chen Kuan-Hsing, Asia As Method: Toward Deimperialization (Durham [N.C.]: Duke University Press, 2010), 243–45, 250, 252–55. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 950.072 CHE) ↩

-

Ha Dao, Facebook message to author, 25 Mar 2018. ↩

-

Minzayar Oo, Facebook message to author, 25 Mar 2018. ↩

-

Ahmad Salman, Facebook message to author, 25 Mar 2018. ↩

-

Zheng Gu, “Introduction,” The Chinese Photobook: From the 1900s to the Present, ed. Martin Parr and WassinkLundgren (New York: Aperture Foundation, 2015), 13. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RART 770.951 CHI) ↩

-

Liang Wen Gui 梁文贵, Ren min zhen xian xuan yan 人民阵线宣言 [The people and the country] (新加坡: 人民阵线, 1972). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 329.95957 LWK) ↩

-

I would like to acknowledge Clare Veal’s help in double-checking the English transliteration of these Thai terms denoting the photobook. ↩

-

Akkara Naktamna, Facebook message to author, 25 Mar 2018. ↩

-

Manit Sriwanichpoom, e-mail message to author, 26 Mar 2018. ↩

-

Manit Sriwanichpoom, Facebook message to author, 23 Jun 2018. ↩

-

Yudhi Soerjoatmodjo, “Beyond Pictorialism: Photography in Modern Indonesia,” in Toward Independence: A Century of Indonesia Photographed, ed. Jane Levy Reed (San Francisco: Friends of Photography, 1991), 119. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RUR 959.800222 REE) ↩

-

My interest in Indonesian photobooks was germinated by PannaFoto Institute when they funded my research trip to Jakarta in December 2015 to interview its founding members, alumni and collaborators for another book project. ↩

-

Erik Prasetya, interview by author, Jakarta, Indonesia, 21 Jun 2009. ↩

-

Ahmad Salman, Facebook message to author, 11 Jul 2016. ↩

-

Faisal Aziz, Facebook message to author, 17 Feb 2014. ↩

-

Ridzki Noviansyah, interview by author, Jakarta, Indonesia, 15 Dec 2015. ↩

-

Ng Swan Ti, interview by author, Jakarta, Indonesia, 14 Dec 2015. ↩

-

Aditya Pratama, e-mail message to author, 26 Mar 2018. ↩

-

Akkara Naktamna, e-mail message to author, 28 Mar 2018. ↩

-

Aditya Pratama, Photo Books From Indonesia – Development and Role of Communities, November 2017, accessed 30 June 2018, https://www.goethe.de/ins/id/en/kul/mag/21126073.html. ↩

-

Felix Laureano, Recuerdos de Filipinas : album-libro : util para el estudio y conocimiento de los usos y costumbres de aquellas islas con treinta y siete fototipias tomadas y copiadas del natural [Memories of the Philippines: Album-book; A tool for the study and understanding of the ways and customs of these islands with thirty-seven phototypies taken and copied from real life] (Mandaluyong, Philippines: Cacho Publishing House, 2001). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.9 LAU) ↩

-

The Long and Winding Road East Timor (Jakarta: Alliance of Independent Journalists, 2001). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RART q779.91598092 HAS) ↩

-

Sheila S. Coronel, Memory of Dances (Manila: Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, 2002). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.90049921 COR) ↩

-

Sheila S. Coronel, e-mail message to author, 29 Mar 2018. ↩

-

Sheila S. Coronel, e-mail message to author, 4 Apr 2018. ↩

-

Tommy Hafalla, Ili (Manila: MAPA Books, 2016). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RART 779.2095991 HAF) ↩

-

RJ Fernandez, e-mail message to author, 4 Apr 2018. ↩

-

Pratama, Photo Books From Indonesia – Development and Role of Communities. ↩

-

Ng, interview, 14 Dec 2015. ↩

-

Reginald Davis, The Royal Family of Thailand (London: Nicholas Publications, 1981). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.3040924 DAV) ↩

-

Malaiya lao gong dang li shi tu pian ji 马来亚劳工党历史图片集 [Labour Party of Malaya album of historical photographs] (吉隆坡:劳工党党史全国工委会, 2000). (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RSING 324.259507 MLY-[YOS]) ↩

-

Cheah Boon-Kheng, “The Left-Wing Movement in Malaya, Singapore and Borneo in the 1960s: ‘An Era of Hope or Devil’s Decade’?” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 7, no. 4 (December 2006): 639–43, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14649370600983196. ↩

-

Malaiya lao gong dang li shi tu pian ji, 152–56. ↩

-

Malaiya lao gong dang li shi tu pian ji, 170–78. ↩

-

Zhuang Wubin 庄吴斌, Shi hui dong nan ya she ying jiao xue de tu pu 试绘东南亚摄影教学的图谱 [Teaching photography in Southeast Asia: Altentative mapping] (台北市: 国立台北艺术大学关渡美术馆, 2017). (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RSEA 770.71059 ZWB) ↩

-

Photographic Society of Singapore, Photographic Society of Singapore, Seven Men Photo Exhibition at the Victoria Memorial Hall, 6th and 7th March, 1965 ([Singapore: Photographic Society of Singapore, 1965]). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 779 PHO) ↩

-

Photographic Society of Singapore, Photographic Society of Singapore, Seven Men Photo Exhibition at the Victoria Memorial Hall, 6th and 7th March, 1965, foreword. ↩

-

Photographic Society of Singapore, Photographic Society of Singapore, Seven Men Photo Exhibition at the Victoria Memorial Hall, 6th and 7th March, 1965, 135. ↩

-

Renhui Robert Zhao, Mynas (Singapore: Institute of Critical Zoologists, 2016). (From PublicationSG) ↩

-

Chua Tiag Ming 蔡哲民, Zhemin ying ji 哲民影集 [Photography in action] (Singapore: s.n., 1978). (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese R 779 CTM) ↩

-

Chua, Zhemin ying ji, 1. ↩

-

Brunei Shell Petroleum Company, Brunei Darus Salam: Gambar2 Menunjokkan Negeri Dan Pendudok-Nya [Brunei Darus Salam: A pictorial review of the land and people] ([Seria]: Brunei Shell Petroleum, [1968?]). (From National Library, Singapore call no. Malay R 959.55 BRU) ↩

-

Chen, Asia As Method: Toward Deimperialization, 237. ↩

-

Chen, Asia As Method: Toward Deimperialization, 240. ↩

-

Feng zhi juan: Xing Hua tu zhi 风之卷: 兴华图志 [A pictorial history of Hin Hua High School]. (Malaysia: 兴华中学, 2013), 13. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RSEA 373.5951 XHZ ↩

-

Marjorie Doggett, Characters of Light: A Guide to the Buildings of Singapore (Singapore: Donald Moore, 1957). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 722.4095957 DOG) ↩

-

Doggett, Characters of Light, vi. ↩

-

Doggett, Characters of Light, vii–ix. ↩

-

Marjorie Doggett, Characters of Light (Singapore: Times Books International, 1985). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 722.4095957 DOG) ↩

-

Doggett, Characters of Light, viii. ↩